On this day on 30th July

On this day in 1718 William Penn died.

William Penn, the son of Sir William Penn (1621-70), was born in 1644. Penn was sent down from Oxford University for refusing to conform to the restored Anglican Church.

Admiral Penn sent his son France, hoping that he would lose his Puritan beliefs. He returned to study law in London and in 1666 went to Ireland where he managed his father's estates in Cork. While in Ireland he attended Quaker meetings and this led to his arrest and imprisonment.

Penn moved back to England and was soon in trouble for writing Sandy Foundation Shaken. This attack on the Anglican Church resulted in him being imprisoned in the Tower of London. While in prison Penn wrote No Cross, No Crown and Innocency With Her Open Face. He was eventually released but in 1671, Penn, now a devout Quaker, was sent to Newgate Prison for six months for preaching. On his release he made a preaching tour of Holland and Germany where he advocated toleration of all religious faiths.

In 1681 William Penn purchased a large area of land in America from Charles II. Penn saw the venture as a "holy experiment" and hoped he would be able to establish a colony where people of all creeds and nationalities could live together in peace. The first settlers began arriving in Pennsylvania in 1682 and settling around Philadelphia (the city of brotherly love) at the junction of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers.

Penn returned to London in 1684 and led the campaign for religious toleration in England. Two years later, all people imprisoned on account of their religious opinions, including 1200 Quaker, achieved their freedom.

In 1689 Penn returned to Pennsylvania and made changes to a constitution which had proved to be unworkable. This included conflicts over the keeping of slaves. William Penn died on 30th July 1718.

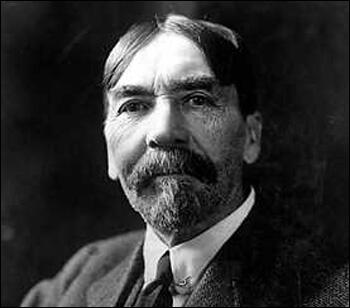

On this day in 1857 Thorstein Veblen, the son of a farmer, was born in Manitowoc County, Wisconsin, on 30th July, 1857. His parents were Norwegian immigrants and he did not learn to speak English until he went to school. A brilliant student, Veblen attended Johns Hopkins University before obtaining his PhD from Yale University in 1884.

Unable to find work as a teacher, Veblen returned to the family farm. His short-term financial worries came to an end when he married the wealthy heiress, Ellen Rolfe, in 1888. He entered Cornell University in 1891 and the following year became a lecturer in the economics department at the University of Chicago. Veblen also began editing the Journal of Political Economy (1892-1905) where he pioneered the idea of economic sociology.

Veblen's first book, The Theory of the Leisure Class, was published in 1899. The book attempted to apply Darwin's theory of evolution to the modern economy. Veblen argued that the dominant class in capitalism, which he labelled as the "leisure class", pursued a life-style of "conspicuous consumption, ostentatious waste and idleness". He also upset the academic world when he claimed that higher learning was marked by "conspicuous consumption".

Veblen's next book, The Theory of Business Enterprise (1904), looked at what he believed was the incompatibility between the behaviour of the capitalist with the modern industrial process. Veblen argued that the new industrial processes impelled integration and provided lucrative opportunities for those who managed it. Veblen believed this resulted in a conflict between businessmen and engineers.

Henry Agard Wallace argued that Veblen's "books were among "the most powerful produced in the United States in this century". He arranged a meeting with Veblen and later recalled that he found him "a mousy kind of man... not a particularly attractive person." However, he was "dazzled by his brilliant mind" and was deeply influenced by his views on capitalism, nationalism and militarism. Wallace observed that the economist was one of the few men who really "knew what was going on". Wallace admitted that Veblen "had a marked effect on my economic thinking."

After being accused of marital infidelity Veblen was forced to leave the University of Chicago. He became associate professor at Stanford University until another scandal in 1909 resulted in him moving to the University of Missouri. Veblen obtained a divorce in 1914 and married his long-time friend, Anne Bradley.

Veblen's criticism of modern capitalism continued in The Instinct for Workmanship (1914). He followed this with Imperial Germany and the Industrial Revolution (1915). This book explored the economic differences between the democratic states of England and France with the autocratic Germany.

An opponent of America's entry into the First World War, in his book, An Inquiry into the Nature of Peace and the Terms of its Perpetuation (1917), he argued that war was caused mainly by the competitive demands of international capitalism. Long-term peace, he believed, would need government controls over the way the capitalist economy functioned.

As well as contributing to several literary and political journals, Veblen published several more books including Higher Learning in America (1918), The Vested Interests and the Comman Man (1919), The Place of Science in Modern Civilization (1920), The Engineers of the Price System (1921) and Absentee Ownership and Business Enterprise (1923). In his last book Veblen pointed out that business tended naturally to develop into the giant corporation and then, the separation of ownership and management.

Thorstein Veblen remained a pessimist and although a strong critic of capitalism he never embraced alternative socialist economic theories. His work was largely ignored at the time of his death on 3rd August, 1929. However, there was renewed interest Veblen's theories during the Economic Depression of the 1930s and his supporters claimed that his criticisms of capitalism had been vindicated.

On this day in 1863 Henry Ford, the second of eight children, son of William Ford (1826–1905) and Mary Litogot Ford (1839–1876), was born in Greenfield, Michigan on 30th July, 1863. He was the grandson of John Ford, a Protestant tenant farmer who had come to America from Ireland during the great potato famine of 1847.

William Ford had a farm of eighty acres. According to Henry's biographer, Andrew Ewart: "He showed an early facility for repairing clocks and watches but at home on the farm he had to take his share of the inevitable chores, chopping wood, milking cows, learning to harness a team of horses. When he was twelve he was ploughing and doing a man-sized job on the farm. He had no education in science - he got his considerable mechanical knowledge from experience."

Ford was very close to his mother and was devastated when she died when he was only thirteen. In 1879, against the wishes of his father, he moved to Detroit where he found work at the James Flowers Machine Shop. He was assigned to mill hexagons onto brass valves. Ford was pleased to be away from his father and grandfather. He later wrote, "I never had any particular love for the farm - it was the mother on the farm I loved."

Within a year he had moved to the Detroit Dry Dock Engine Works, the largest shipbuilding firm in the city. He worked a sixty-two-hour week in a machine shop, while, to earn a bit extra, repairing watches in a jewellery store six nights a week as well. Later he travelled round Michigan farms servicing Westinghouse steam engines.

At this time Detroit was a city that offered plenty of opportunities of work. It had a population of more than 116,000 people, covering an area of seventeen square miles - an industrial, shipping, and railroad hub with nearly 1,000 manufacturing and mechanical establishments, twenty miles of street railways, a telegraph network, and a waterworks.

On the death of his grandfather he returned to help his father manage the family farm. He was also given 40 acres to start his own farm. In 1886 Henry Ford met Clara Bryant, the twenty-year-old daughter of a local farmer. He told his sister Margaret that in thirty seconds that he knew this was the girl of his dreams. In April 1888 Henry married Clara, who was three years younger than himself.

During this period Ford read an article in a magazine about how the German engineer, Nicholas Otto, had built a internal combustion engine. One night, after returning from repairing an Otto engine that belonged to a friend, he told his wife that he intended to build a "horseless carriage". Ford disliked farming and spent much of the time trying to build a steam road carriage and a farm locomotive.

In September, 1891, he returned to Detroit to work as an engineer for the Edison Illuminating Company. The couple moved into a two-story house, a short walk from the works. Ford was extremely ambitious and eventually became chief engineer at the plant at a salary of 100 dollars a month. Soon afterwards, on 9th November, 1893, his son and only child, Edsel, was born.

His first vehicle, called a Quadricycle, was finished in June 1896, was built in a little brick shed in his garden. "With a two-cylinder petrol engine, a bicycle seat, a wooden chassis and bicycle tyres on its spindly wheels, it was steered by a tiller and had a house bell as a horn. It weighed only 500 pounds and had a top speed above 20mph, though rival machines rarely exceeded 5mph. Embarrassingly, the completed Quadricycle was too big to get out through the door of the shed and Ford had to demolish part of the wall with an axe."

Two months later Henry Ford attended a meeting of members of the National Association of Edison Illuminating Companies in the Oriental Hotel in Brooklyn. At the meeting, Ford's boss, Alexander Dow, introduced him to Thomas Edison with the words: "Young fellow here has made a gas car." Edison was curious and began to pepper Ford with detailed questions. Ford drew a picture of his machine on a scrap of paper. Edison was impressed and told him to "keep at it!" From that moment onward, Ford's admiration ripened into hero worship "like a planet that had adopted Edison for its sun."

Henry Ford carried on with his job at the Edison plant while he set about designing and building his second car. However, he was told by his bosses: "You can work on your car or you can work for us - but not both." Ford now approached a group of businessmen to fund the venture. He was originally given $15,000 to build ten cars. Ford established the Detroit Automobile Company and was determined that cars would be as near perfect as he could make it and insisted on improving the carburation system. His refusal to put the car into production until he was satisfied with it, infuriated investors. After spending $86,000 ($2.15 million in today's money) on the project the company collapsed in January 1901.

Ford decided to establish himself with the public by building a racing car. He challenged, Alexander Winton, the most famous racing driver of the day, to a race at Grosse Pointe. Ford won an event styled "the first big race in the west" by almost a mile. Ford later recalled: That was my first race, and it brought advertising of the only kind that people cared to read." After this he had no trouble in raising the money to start a new company. On 23rd November, 1901, Henry Ford sold 6,000 shares at a par value of ten dollars each.

By this time there were several other companies manufacturing cars. Ford suffered from production delays, and this caused conflict with his shareholders and once again the company collapsed. Disillusioned by his lack of success in producing motor cars for the road and decided to return to racing cars. The first one, The Arrow, crashed during a race in September 1903, killing its driver, Frank Day. His second car, Ford 999, driven by Barney Oldfield, was a great success. On 12th January, 1904, Henry Ford drove the 999 to a speed of 91.37 mph (147.05 km/h).

Ford recruited Oliver E. Barthel, a talented young mechanic and engineer. He later recalled that “Henry Ford was a cut-and-try mechanic without any particular genius.” He was also concerned about what he considered to be Ford's dual nature: "One side of his nature I liked very much and I felt that I wanted to be a friend of his. The other side of his nature I just couldn't stand. It bothered me greatly. I came to the conclusion that he had a particular streak in his nature that you wouldn't find in a serious-minded person."

Alexander Malcolmson, a coal dealer in Detroit, was very impressed with the Ford 999 and decided to make a substantial investment in Henry Ford. The partnership began in August 1902. He also persuaded some of his friends to back Ford and by June, 1903, there were twelve stockholders who between them had raised $28,000 in cash to float the company. Ford and Malcolmson owned over 50% of the company.

As a result of Ford's earlier problems, Malcolmson installed his clerk James Couzens at Ford Motor in a full-time position. Couzens borrowed heavily and invested $2,500 in the new firm. Ford Motor Company was founded in 1903 with John Simpson Gray as president, Ford as vice-president, Malcolmson as treasurer, and Couzens as secretary. Couzens took over the business management of the new firm for a salary of $2,400.

The Ford Motor Company was only one of 150 automobile manufactures that were active in the United States. Ford now set about making what became known as the Model T (also known as the Tin Lizzie or Leaping Lena). He told his investors: "I will build a car for the great multitude. It will be large enough for the family, but small enough for the individual to run and care for. It will be constructed of the best materials, by the best men to be hired, after the simplest designs that modern engineering can devise. But it will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one – and enjoy with his family the blessing of hours of pleasure in God's great open spaces."

A petrol engine patent was granted in 1895 to George Baldwin Selden. Therefore all car manufacturers were required to pay royalties to the lessee of the patent. To protect themselves these manufacturers had formed an association and had arranged with the lessee of the patent, the Electric Vehicle Company, to control the industry. Ford refused to join the organisation and instead challenged the validity of the patent.

The first Model T car left the factory on 27th September, 1908. The first cars were assembly by hand, and production was small. Only eleven cars were built during the first month of production. It was sold for $825 and this made it the cheapest in the market. Early sales were very encouraging. Ford also introduced the latest marketing methods. His publicity department ensured that newspapers carried stories about the Model T. In 1909 Ford produced 10,600 cars and that year his company made a profit of over a million dollars. According to William Davis, the "Model T had two undeniable merits: it was efficient and it was cheap. Ford's innovative concept was a reliable car that would sell for no more than the price of a horse and buggy."

Since 1908 Ford had spent around $2,000 a week defending himself against the other car manufacturers. In 1910 the court upheld Selden's patent. The verdict could have put him out of business. However, he now appealed to a higher court: "It is said that everyone has his price, but I can assure you that, while I am head of the Ford Motor Company there will be no price that would induce me to add my name to the association." Dealers were warned not to sell his "unlicensed cars". Times were very difficult for Ford until the United States Court of Appeals gave out its verdict completely upholding all his contentions with regard to the patent.

Sales were so good that his Piquette Plant could not keep up with demand. Ford therefore decided to move his operations to the specially built Highland Park Ford Plant. Over 120 acres in size it was the largest manufacturing facility in the world at the time of its opening. In 1913, the Highland Park Ford Plant became the first automobile production facility in the world to implement the assembly line.

Ford had been influenced by the ideas of Frederick Winslow Taylor who had published his book, Scientific Management in 1911. Peter Drucker has pointed out: "Frederick W. Taylor was the first man in recorded history who deemed work deserving of systematic observation and study." Ford took on Taylor's challenge: "It is only through enforced standardization of methods, enforced adoption of the best implements and working conditions, and enforced cooperation that this faster work can be assured. And the duty of enforcing the adoption of standards and enforcing this cooperation rests with management alone."

Initially it had taken 14 hours to assemble a Model T car. By improving his mass production methods, Ford reduced this to 1 hour 33 minutes. This lowered the overall cost of each car and enabled Ford to undercut the price of other cars on the market. By 1914 Ford had made and sold 250,000 cars. Those manufactured amounted for 45% of all automobiles made in the USA that year.

On 5th January 1914, on the advice of James Couzens, the Ford Motor Company announced that the following week, the work day would be reduced to eight hours and the Highland Park factory converted to three daily shifts instead of two. The basic wage was increased from three dollars a day to an astonishing five dollars a day. This was at a time when the national average wage was $2.40 a day. A profit-sharing scheme was also introduced. Unfortunately, the women working at the plant remained on two dollars a day.

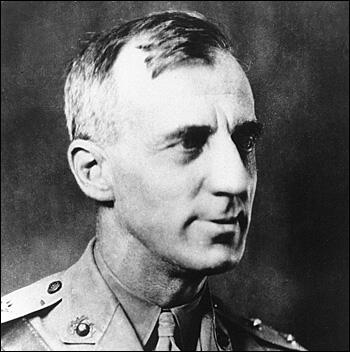

On this day in 1881 Smedley Butler was born in Pennsylvania. His father, Thomas Stalker Butler, was a lawyer and politician and in 1897 was elected to the House of Representatives.

Butler was educated at the Haverford School, a private secondary school for the sons of wealthy Quaker families in Philadelphia. Although brought up as a pacifist he runaway from school at sixteen to join the army. Butler lied about his age and secured a second lieutenant's commission in the US Marines.

After six weeks of basic training Butler was sent to Guantanamo, Cuba, in July 1898. He saw action against the Spanish before being sent to China during the Boxer Rebellion. At the Battle of Tientsin on 13th July, 1900, Butler was shot in the thigh when he climbed out of a trench to retrieve a wounded officer. In recognition of his bravery Butler was promoted to the rank of captain. Butler was badly wounded for a second time when he was shot in the chest at San Tan Pating. In 1903, Butler was sent to Honduras where he protected the U.S. Consulate from rebels.

In 1914 Butler won the Medal of Honor for outstanding gallantry in action while fighting against the Spanish at Veracruz, Mexico. Major Butler returned his medal arguing that he had not done enough to deserve it. It was sent back to Butler with orders that not only would he keep it, but that he would wear it as well. Butler won his second Medal of Honor in Haiti on 17th November, 1915.

Promoted to the rank of brigadier general at the age of 37 he was placed in command of Camp Pontanezen at Brest, France, during the First World War. This resulted in him being awarded the Distinguished Service Medal and the French Order of the Black Star.

Following the war, Butler transformed the wartime training camp at Quantico, Virginia into a permanent Marine post. In 1923 the newly elected mayor of Philadelphia, W. Freeland Kendrick, asked Butler to leave the Marines to become Director of Public Safety. Butler refused but eventually accepted the appointment in January 1924 when President Calvin Coolidge requested him to carry out the task.

Butler immediately ordered raids on more than 900 speakeasies in Philadelphia. He also ordered the arrests of corrupt police officers. Butler upset some very powerful people in his crusade against corruption and in December 1925 Kendrick sacked Butler. He later commented "cleaning up Philadelphia was worse than any battle I was ever in."

Butler returned to the US Marines and in 1927 was appointed the commander of the Marine Expeditionary Force in China. Over the next two years he did what he could to protect American people living in the country.

At the age of 48, Butler became the Marine Corps' youngest major general. Butler became the leading figure in the struggle to preserve the Marine Corps' existence against critics in Congress who argued that the US Army could do the work of the Marines. Butler became a nationally known figure in the United States by taking thousands of his men on long field marches to Gettysburg and other Civil War battle sites, where they conducted large-scale re-enactments before large crowds of spectators.

In 1931, Butler said in an interview that Benito Mussolini had allegedly struck a child with his automobile in a hit-and-run accident. Mussolini protested and President Herbert Hoover instructed the Secretary of the Navy to court-martial Butler. Butler became the first general officer to be placed under arrest since the Civil War. Butler was eventually released without charge.

Major General Wendell C. Neville died in July 1930. Butler was expected to succeed him as Commandant of the Marine Corps. However, he had upset too many powerful people in the past and the post went to Major General Ben Hebard Fuller instead. Butler retired from active duty on 1st October, 1931.

In 1932, Butler ran for the U.S. Senate in the Republican primary in Pennsylvania, allied with Gifford Pinchot, the brother of Amos Pinchot, but was defeated by James J. Davis.

Butler went to Senator John McCormack and told him that there was a fascist plot to overthrow President Franklin Roosevelt. Butler claimed that on 1st July 1934, Gerald C. MacGuire a Wall Street bond salesman and Bill Doyle, the department commander of the American Legion in Massachusetts, tried to recruit him to lead a coup against Roosevelt. Butler claimed that the conspirators promised him $30 million in financial backing and the support of most of the media.

Butler pretended to go along with the plot and met other members of the conspiracy. In November 1934 Butler began testifying in secret to the Special Committee on Un-American Activities Authorized to Investigate Nazi Propaganda and Certain Other Propaganda Activities (the McCormack-Dickstein Committee). Butler claimed that the American Liberty League was the main organization behind the plot. He added the main backers were the Du Pont family, as well as leaders of U.S. Steel, General Motors, Standard Oil, Chase National Bank, and Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company.

Butler also named Prescott Bush as one of the conspirators. At the time Bush was along with W. Averell Harriman, E. Roland Harriman and George Herbert Walker, managing partners in Brown Brothers Harriman. Bush was also director of the Harriman Fifteen Corporation. This in turn controlled the Consolidated Silesian Steel Corporation, that owned one-third of a complex of steel-making, coal-mining and zinc-mining activities in Germany and Poland. Friedrich Flick owned the other two-thirds of the operation. Flick was a leading financial supporter of the Nazi Party and in the 1930s donated over seven million marks to the party. A close friend of Heinrich Himmler, Flick also gave the Schutz Staffeinel (SS) 10,000 marks a year.

On 20th November, 1934, the story of the alleged plot was published in the Philadelphia Record and the New York Post. Four days later the McCormack-Dickstein Committee released its preliminary findings and the full-report appeared on 15th February, 1935. The committee reported: "In the last few weeks of the committee's official life it received evidence showing that certain persons had made an attempt to establish a fascist government in this country... There is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient."

Although the McCormack-Dickstein Committee claimed they believed Butler's testimony they refused to take any action against the people he named as being part of the conspiracy. Butler was furious and gave a radio interview on 17th February, 1935, where he claimed that important portions of his testimony had been suppressed in the McCormack-Dickstein report to Congress. He argued that the committee, had "stopped dead in its tracks when it got near the top." Butler added: "Like most committees, it has slaughtered the little and allowed the big to escape. The big shots weren't even called to testify. Why wasn't Colonel Grayson M.-P. Murphy, New York broker... called? Why wasn't Louis Howe, Secretary to the President of the United States, called? Why wasn't Al Smith called? And why wasn't General Douglas MacArthur, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, called? And why wasn't Hanford MacNider, former American Legion commander, called? They were all mentioned in the testimony. And why was all mention of these names suppressed from the committee report?"

John L. Spivak, who had been mistakenly given access to the unexpurgated testimony of the people interviewed by the McCormack-Dickstein Committee. He published an article in the New Masses entitled Wall Street's Fascist Conspiracy on 5th February 1935. This included the claim that "Jewish financiers" had been working with "fascist groups" in an attempt to overthrow President Franklin Roosevelt. The article was dismissed as communist propaganda.

In November 1935 Smedley Butler wrote an article for the socialist magazine Common Sense: "I spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. I helped purify Nicaragua for the International Banking House of Brown Brothers in 1902-1912. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar interests in 1916. I helped make Honduras right for the American fruit companies in 1903. In China in 1927 I helped see to it that Standard Oil went on its way unmolested."

Butler also published a book entitled War is a Racket (1935). It was a powerful denunciation of war. He wrote: "In the (First) World War a mere handful garnered the profits of the conflict. At least 21,000 new millionaires and billionaires were made in the United States during the World War. That many admitted their huge blood gains in their income tax returns. How many other war millionaires falsified their tax returns no one knows. How many of these war millionaires shouldered a rifle? How many of them dug a trench? How many of them knew what it meant to go hungry in a rat-infested dug-out? How many of them spent sleepless, frightened nights, ducking shells and shrapnel and machine gun bullets? How many of them parried a bayonet thrust of an enemy? How many of them were wounded or killed in battle?"

Smedley Butler continued to campaign against the Military Industrial Complex until his death on 21st June 1940.

On this day in 1909 Emily Wilding Davison was arrested when she disrupted a speech being made by David Lloyd George at Limehouse in London. "We went outside Lloyd George's meeting at Limehouse. I was busy haranguing the crowd when the police came up and arrested me. We were charged next day at Thames Police Court. I and Mrs. Leigh got the longest sentences, i.e., two months, the rest mostly got two weeks. The governor told us that if we went quietly to our cells we could keep our clothes. Then they took us off one by one after a struggle. When I was shut in the cell I at once smashed seventeen panes of glass. Then they rushed me into another cell. They forcibly undressed me and left me sitting in a prison chemise. Then I was dressed in prison clothes and taken into one of the worst cells, very dark, with double doors."

On this day in 1962 Nora Smyth died and is buried in St. Bartholomew's Churchyard, Barrow, Cheshire.

In 2018 Four Corners Gallery in Roman Road, mounted the first ever exhibition of Ethel Smyth's photographs. As Jane McChyrstal pointed out the photographs "cast a sympathetic eye on the women and children of the East End, in contrast to those reporters who came here in search of scenes of poverty and degradation. We can only hope it was a first step on the road to the widespread recognition she deserves."

Norah Smyth was born on 22 nd March 1874. Her father inherited a fortune from a wealthy Liverpool grain dealer. She was the niece of Ethel Smyth. Her father controlled many aspects of her life, refusing her permission to attend university or marry her cousin, as she had hoped.

Smyth's father died in 1912 leaving her a considerable amount of money. For some time she had been interested in the struggle for women's suffrage and joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), working as an unpaid chauffeur for Emmeline Pankhurst.

Norah was also in the theatre and joined Edith Craig in her creation of the Pioneer Players, her feminist theatre company. Craig became internationally known for promoting women's work in the theatre. Ellen Terry was president of the Pioneer Players and Christabel Marshall contributed as dramatist, translator, actor and a member of the advisory and casting committees. One of the first productions of the group was In the Workhouse, a play written by Margaret Nevinson, one of the leaders of the Women's Freedom League (WFL). The play, based on a true story, told of how a man who used the law to keep his wife in the workhouse against her will. As a result of the play, the law was changed in 1912.

Norah became close friends with Sylvia Pankhurst. According to Patricia W. Romero: "Norah Smyth, a tall, dark, thin, handsome woman, dressed in the liberated fashion of the period, wearing ties and dressing as much like a man as possible. This affection in dress reflected the desire for emancipation and was common among the more liberated, especially those, like Nora, who could afford the new style. On the other hand, both Norah and Sylvia came to accept that were for the time very advanced views on matters pertaining to sexual liberation. We know nothing about the complexities of their personal relationship. Norah never married. Sylvia herself was deeply in love with Keir Hardie in these years."

In July 1912, Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote.

On 13 July 1912 Helen Craggs and another woman were found by P.C. Godden at one o'clock in the morning outside the country home of the colonial secretary Lewis Harcourt. He went towards them and asked them what they were doing. Craggs, said they were looking round the house. The policeman said, "This is not a very nice time for looking round a house. How did you come here? Where do you come from?" Craggs said that they had been camping in the neighbourhood. The police-constable said he had not seen any encampment. She then said they had arrived by the river. Godden seized Miss Craggs and arrested her, and she was taken into custody.

Helen Craggs appeared at Bullingdon Petty Sessions the next day. According to Votes for Women, "Miss Craggs, who carried a bunch of flowers in the colours, was evidently the centre of much sympathy from the public in the Court." (8) Helen pleaded guilty to the charge of "being in the garden…. For an unlawful purpose, to commit a felony, to unlawfully and maliciously set fire to a house and building belonging to Mr Harcourt". The judge argued that because of the seriousness of the crime - eight people were asleep in the house - bail was refused.

The police suspected that the other woman was Ethel Smyth. She was arrested the next day but was released as "she was able without difficulty to satisfy the Bench completely as to her movements on the night in question." Over fifty years later Norah Smyth confided the truth to her nephew, former diplomat Kenneth Isolani Smyth, that she was the woman with Helen Craggs in the attempt to set fire to Harcourt's house. "He expressed surprise, knowing her love of old paintings and antiques, but Smyth explained that she knew the east wing of the house was uninhabited. It was the only violent action that she undertook as a suffragette."

In January 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst made a speech where she stated that it was now clear that Herbert Asquith had no intention to introduce legislation that would give women the vote. She now declared war on the government and took full responsibility for all acts of militancy. "Over the next eighteen months, the WSPU was increasingly driven underground as it engaged in destruction of property, including setting fire to pillar boxes, raising false fire alarms, arson and bombing, attacking art treasures, large-scale window smashing campaigns, the cutting of telegraph and telephone wires, and damaging golf courses".

The WSPU used a secret group called Young Hot Bloods to carry out these acts. No married women were eligible for membership. The existence of the group remained a closely guarded secret until May 1913, when it was uncovered as a result of a conspiracy trial of eight members of the suffragette leadership, including Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Rachel Barrett. It has speculated that this group included Nora Smyth, Helen Craggs, Olive Hockin, Kitty Marion, Lilian Lenton, Miriam Pratt, Clara Giveen, Hilda Burkitt, Olive Wharry and Florence Tunks.

On 19th February, 1913, an attempt was made to blow up a house which was being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, near Walton Heath Golf Links. "One device had exploded, causing about £500 worth of damage, while another had failed to ignite." Sir George Riddell who had commissioned the house, wrote in his diary that Lloyd George: "Said the facts had not been brought out and that no proper point had been made of the fact that the bombs had been concealed in cupboards, which must have resulted in the death of 12 men had not the bomb which first exploded blown out the candle attached to the second bomb, which had been discovered, hidden away as it was. He was very indignant." (Lloyd George wrote to Riddell and apologised for being "such a troublesome and expensive tenant" and that the WSPU should be made to pay for the damage.

That evening in a speech at Cory Hall, Cardiff, Emmeline Pankhurst declared "we have blown up the Chancellor of Exchequer's house' and stated that "for all that has been done in the past I accept responsibility. I have advised, I have incited, I have conspired". Pankhurst concluded that extreme methods were needed because "No measure worth having has been won in any other way."

Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested and charged with "incitement to commit arson". On 3rd April she was sentenced to three years' penal servitude and immediately went on hunger strike. No attempt was ever made to feed her forcibly and the Prisoners' (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Bill (Cat & Mouse Act), which allowed hunger-striking prisoners to be released to recover their health before being returned to prison, was rushed through to ensure that she did not die in prison.

Police records show that the police suspected Norah Smyth and Olive Hockin of being the people who had carried out the attempt to blow up Lloyd George's house. As Elizabeth Crawford has pointed out: "It is clear from the New Scotland Yard reports of the investigation that Olive Hockin's address had been under surveillance. Her absence from home, the manner of her departure and the time of her return are all noted in the police report."

However, Norah Smyth never admitted to being involved in this attack. In fact, she was now involved in another project with her close friend, Sylvia Pankhurst. With the help of Keir Hardie, Julia Scurr, Mary Phillips, Millie Lansbury, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Joachim, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Jessie Stephen, Nellie Cressall and George Lansbury and Zeli Emerson, they established the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party.

As June Hannam has pointed out: "The ELF was successful in gaining support from working women and also from dock workers. The ELF organized suffrage demonstrations and its members carried out acts of militancy. Between February 1913 and August 1914 Sylvia was arrested eight times. After the passing of the Prisoners' Temporary Discharge for Ill Health Act of 1913 (known as the Cat and Mouse Act) she was frequently released for short periods to recuperate from hunger striking and was carried on a stretcher by supporters in the East End so that she could attend meetings and processions. When the police came to re-arrest her this usually led to fights with members of the community which encouraged Sylvia to organize a people's army to defend suffragettes and dock workers. She also drew on East End traditions by calling for rent strikes to support the demand for the vote."

Norah Smyth supplied most of the money for this venture. Appointed treasurer of the EFL she helped finance their weekly newspaper, The Women's Dreadnought that first appeared in March 1914. Although they printed 20,000 copies, by the third issue total sales were only listed as just over 100 copies. During processions and demonstrations, the newspaper was freely distributed as propaganda for the EFF and the wider movement for women's suffrage.

Sylvia Pankhurst, who had brought an end to her romantic relationship with Keir Hardie, became extremely close to Norah during this period: "Although Norah was also from a wealthy background, she dedicated many years of her life, and almost all of her inheritance, to the suffragette cause, and lived in Bow with Sylvia for many years. Norah played a key role in all the Federation's activities (she was financial secretary, helped to drill the People's Army and even wallpapered and painted the Woman's Hall) but seemed to prefer a place out of the limelight." (24) It has been suggested Norah became a substitute sister for Sylvia.

Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst objected to the formation of the East London Federation of Suffragettes and by the end of 1913 Sylvia was on the verge of being expelled from the WSPU. Christabel, who was living in exile, should meet with her in Paris. "So insistent were the messages… I agreed to go… I was smuggled into a car and driven to Harwich. I insisted that Norah Smyth, who had become financial secretary of the Federation, should go with me to represent our members… Like me, she desired to avoid a breach. Dogged in her fidelities, and by temperament unable to express herself under emotion, she was silent… She (Christabel) urged, a working women's movement was of no value; working women were the weakest portion of the sex: how could it be otherwise? Their lives were too hard, their education too meagre to equip them for the contest." Christabel added: "You have your own ideas. We do not want that; we want all our women to take their instructions and walk in step like an army!".

Christabel also complained about ELF's close links with the Labour Party and the trade union movement. She especially objected to her attending meetings addressed by George Lansbury and James Larkin and her friendship with Keir Hardie and Henry Harben. In view of all this, Christabel concluded, Sylvia's East London suffragettes had to become an entirely separate organization, having proven their inability to operate in compliance with WSPU policy.

Norah continued to provide the money needed to keep the ELF functioning. However, as the authors of the East London Suffragettes pointed out: "One of Nora's greatest contributions was as an observer. She had a talent for photography, and it is thanks to her that we have such a fantastic visual record of the East London suffragettes' activities, and so many images of the deep poverty which surrounded them."

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort, but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided".

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!".

Anti-war activists such as Ramsay MacDonald were attacked as being "more German than the Germans". Another article on the Union of Democratic Control carried the headline: "Norman Angell: Is He Working for Germany?" Mary Macarthur and Margaret Bondfield were described as "Bolshevik women trade union leaders" and Arthur Henderson, who was in favour of a negotiated peace with Germany, was accused of being in the pay of the Central Powers. Her daughter, Sylvia Pankhurst, who was now a member of the Labour Party, accused her mother of abandoning the pacifist views of Richard Pankhurst.

Norah Smyth shared Sylvia's pacifist beliefs and joined her on platforms in the East End, condemning the war and calling for an early peace. Norah wrote in The Women's Dreadnought that "peace would be the overriding issue in the year to come". Former WSPU members such as Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth joined them on ELFS demonstrations against the war.

In 1914 Norah and Henry Harben agreed to finance the establishment of the Women's Hall at 400 Old Ford Road in Bow. It was large enough to hold meetings of 350 people. It became the headquarters of the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS). It became a social centre run largely by and for local working-class women. It housed a ‘Cost Price Restaurant' where people could get a hot meal at a very low price and free milk for their children.

In October 1914 Norah agreed to finance the establishment of a toy factory at the rear of the Women's Hall. The first toys were wooden and flat, easily made and quickly marketable. The socialist artist Walter Crane provided free designs. Since the Germans had cornered most of the toy market before the war, especially the production of dolls, it seemed to be a good idea. Eventually the factory produced stuffed dolls that they sold to Selfridge's in the West End. When the factory started making profits, Norah turned it into a cooperative and hired Regina Hercbegova as manager.

The factory was supposed to be run collectively, guided by a definite constitution and a workers' committee. Unbeknown to Norah Smyth, Hercbegova set up her own business management system. "Regina swiftly grasped the most effective capitalist methods – cost cutting, increasing her own wages and decreasing those of the staff – while running roughshod over the co-operative, socialist ethos on which the factory was supposed to run."

Regina Hercbegova ran the factory very badly and it was soon heavily in debt. By the end of the war had sold jewels, cashed bonds and sold antique furniture to keep the venture going. In all, Norah lent the factory £750. Norah also financed other ventures. Indeed, between February 1915 and July 1916, Norah lent the ELF a total of £1839 10s 4d.

Despite the problems with the factory, the Women's Hall was a great success: "With a large hall of their own, the suffragettes were able to hold public meetings without fear of interference from the council or the police. Other sympathetic groups could hold their meetings there too, bringing in a new audience for the Federation's messages and building solidarity with other campaigns in the East End at the time. Without having to pay hire fees, the Federation could run a much wider range of activities, including lessons and workshops, fundraising concerts, lending libraries, affordable canteens and nurseries."

Norah and Sylvia formed a branch of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom in the East End. In a continuing attempt to maintain a balance between suffrage and peace agitation the East London Federation of Suffragettes changed its name in March 1916 to the Workers Suffrage Federation (WSF), symbolically acknowledging its long-held goal of universal suffrage. (40)

Norah and Sylvia, although critical of those who supported Britain's entry into the First World War, they admired those who attempted to reduce the suffering in the conflict. This included Henry Harben who had financed a hospital treating wounded soldiers in France that was being run by another former WSPU member, Dr. Flora Murray. They showed their approval by visiting the hospital in Paris. (41)

The women's hostility to the war resulted in people resigning from the WSF. As Sylvia Pankhurst admitted later: "I felt sorrow in having to tell parents whose sons were at the front that war was wrong and its ideals false… It required an effort to bring myself to do it… I lost old friends and subscribers to our movement."

Norah Smyth, like Sylvia Pankhurst, was a supporter of the Russian Revolution in 1917. Sylvia commented that it was "a great hope in the midst of disaster". The Workers' Suffrage Federation was one of the first organization in Britain to make contact with the revolutionaries in Russia. In an article published in the Workers Dreadnought, she wrote about how the suffrage movement could learn from the events in Russia.

The Workers Dreadnought starting publishing articles by Marxists such as Claude McKay and Max Eastman. It also included translations of Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and Leon Trotsky. According to Patricia Romero, Norah Smyth became a Soviet agent carrying messages from Moscow to Germany, Italy, France and England.

On 31st July, 1920, a group of revolutionary socialists attended a meeting at the Cannon Street Hotel in London. The men and women were members of various political groups including the British Socialist Party (BSP), the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), Prohibition and Reform Party (PRP) and the Workers' Socialist Federation (WSF). It was agreed to form the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Early members included Tom Bell, Willie Paul, Arthur McManus, Harry Pollitt, Rajani Palme Dutt, Helen Crawfurd, A. J. Cook, Albert Inkpin, J. T. Murphy, Arthur Horner, John R. Campbell, Bob Stewart and Robin Page Arnot. McManus was elected as the party's first chairman and Bell and Pollitt became the party's first full-time workers. It later emerged that Lenin had provided at least £55,000 (over £1 million in today's money) to help fund the CPGB.

It was agreed that the Workers Dreadnought would become its official newspaper. Sylvia argued that "Communism and the Soviets will liberate mothers from their present economic enslavement and drudging. They will elect their own representatives to the Soviets." However, Lenin already saw Sylvia as an enemy because she was a follower of Rosa Luxemburg. In 1920 he published a pamphlet entitled Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder. He accused her and other left-wing libertarian socialists of "intellectual childishness" and not having "the serious tactics of a revolutionary class."

Sylvia travelled to Moscow to debate with Lenin at the Second Congress of the Third International. She responded to Lenin's call to avoid extremism by arguing "I think one should be more extreme than one is… Though I am a socialist, I have thought a long time in the suffrage movement and I have seen how important it is to be extreme… In politics it is necessary to stand up for extreme ideas… My opinion has proved to be right… I therefore insist upon my point of view."

Special Branch had set traps to catch her as she returned to Britain, but she evaded them. She then openly travelled to Manchester. The Daily Express reported "The revolution has started. Sylvia Pankhurst had returned from Russia. She has re-appeared in the city of her parents and flung the gauntlet full in the face of capitalism."

On 19 October Sylvia Pankhurst was arrested under Regulation 42 of the Defence of the Realm Act. She conducted her own defence and used the court as a platform to express her political opinions. Found guilty the magistrate, Alderman Newton, offered the opinion that "the punishment of six months' imprisonment which I pass on you is quite inadequate".

Granted leave to appeal Norah Smyth provided bail money. Sylvia appeal took place on 5 January 1921. She defended the right to publish articles in the Workers Dreadnought that criticized the government. In support of her argument, she quoted her "heroes", Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, William Blake, William Morris and Edward Carpenter. The judge, Sir John Bell, upheld the sentence.

On her release she continued her debate with Lenin who was now completely in control of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). It demanded she hand over the Workers Dreadnought to the party executive. When she refused, she was expelled from the CPGB. Sylvia replied: "The Communist Party of Great Britain is at present passing through a sort of political measles called discipline which makes it fear the free expression and circulation of opinions within the Party."

Norah Smyth was appalled by the way Sylvia had been treated and she resigned from the CPGB. "Smyth decided to join brother Maxwell in Florence, where she took up a post at the British Institute…. In short, she spent her father's inheritance on funding ELFS, needed to earn a living and realised she could live more cheaply in Italy. Florence had been the choice of home for generations of genteel English people who could no longer afford to maintain their way of life in their homeland."

Smyth later worked for Times of Malta. In 1945, she went to live with her sister Una in County Donegal, leading a quiet rural life.

On this day in 1975 Jimmy Hoffa disappears and is never seen or heard from again. It is possible that Jimmy Hoffa was killed in 1975 to stop him from testifying in front of the House Select Committee on Assassinations. Fellow Mafia suspect in the Kennedy assassination, Sam Giancana, was also murdered at the same time Hoffa disappeared.

In 1989 Kenneth Walton, the head of the FBI's Detroit office, told The Detroit News he knew what happened to Hoffa. “I’m comfortable I know who did it, but it’s never going to be prosecuted because… we would have to divulge informants, confidential sources.”

Just before he died, Frank Sheeran, confessed to author Charles Brandt that he killed Jimmy Hoffa. According to Sheeran, Chuckie O'Brien drove Hoffa, Sheeran and another mobster Sal Briguglio to a house in Detroit. Hoffa and Sheeran went into the house and the other two men drove off. Sheeran says he shot Hoffa twice behind the right ear. After the murder, Sheeran says he left the house and was told Hoffa was cremated. The full story appears in Brandt's book I Heard You Paint Houses (2003).