On this day on 29th December

On this day in 1819 suffrage campaigner Mary Fildes has letter published on the Female Reformers of Manchester organisation. In June 1819 the first Female Union was formed by Alice Kitchen in Blackburn. The next one was in Stockport. "We who form and constitute the Stockport Female Union Society, having reviewed for a considerable time past the apathy, and frequent insult of our oppressed countrymen, by those sordid and all-devouring fiends, the Borough-mongering Aristocracy, and in order to accelerate the emancipation of this suffering nation, we, do declare, that we will assist the Male Union formed in this town, with all the might and energy that we possess, and that we will adhere to the principles, etc., of the Male Union…and assist our Male friends to obtain legally, the long-lost Rights and Liberties of our country."

On 20 July 1819, Mary Fildes established the Society of Female Reformers. She became president and in the first week after its formation over 1000 members joined. The organisation's flag had the figure of Justice on it. The Society of Female Reformers met in the Union Rooms, Manchester every Tuesday evening from six to nine o'clock. (5) It had its own flag "which showed a woman holding the scales of justice and treading the serpent of corruption underfoot."

Ruth Mather has pointed out: "Female Reform Societies emerged in north-west England in the summer of 1819... and were immediately faced with the scorn and revulsion of the conservative press and caricaturists. Female Reformers were described as devoid of morals or religion, and depicted as revolutionary harridans or sexual objects, not to be taken seriously as political actors."

On this day in 1876 progressive factory owner Titus Salt, died. Salt, the son of Daniel Salt, a woolstapler, was born in Morley near Leeds on 20th September, 1803. Daniel Salt was a fairly successful businessman and was able to afford to send Titus to Heath Grammar School. After working for two years at a Wakefield woolstapler, Titus joined the family firm in 1824. Titus, who married Caroline Whitlam in 1830, became the firm's wool buyer. Daniel Salt & Son prospered and became one of the most important textile companies in Bradford.

When Daniel Salt retired in 1833, Titus took over the running of the company. Over the next twenty years Titus Salt became the largest employer in Bradford. Between 1801 and 1851 the population of Bradford grew from 13,000 to 104,000. With over 200 factory chimneys continually churning out black, sulphurous smoke, Bradford gained the reputation of being the most polluted town in England. Bradford's sewage was dumped into the River Beck. As people also obtained their drinking water from the river, this created serious health problems. There were regular outbreaks of cholera and typhoid, and only 30% of children born to textile workers reached the age of fifteen. Life expectancy, of just over eighteen years, was one of the lowest in the country.

George Weerth visited Bradford in 1846: "Every other factory town in England is a paradise in comparison to this hole. In Manchester the air lies like lead upon you; in Birmingham it is just as if you were sitting with your nose in a stove pipe; in Leeds you have to cough with the dust and the stink as if you had swallowed a pound of Cayenne pepper in one go - but you can put up with all that. In Bradford, however, you think you have been lodged with the devil incarnate. If anyone wants to feel how a poor sinner is tormented in Purgatory, let him travel to Bradford."

Titus Salt, who now owned five textile mills in Bradford, was one of the few employers in the town who showed any concern for this problem. After much experimentation, Salt discovered that the Rodda Smoke Burner produced very little pollution. In 1842 he arranged for these burners to be used in all his factories.

In 1848 Salt became mayor of Bradford. He tried hard to persuade the council to pass a by-law that would force all factory owners in the town to use these new smoke burners. The other factory owners in Bradford were opposed to the idea. Most of them refused to accept that the smoke produced by their factories was damaging people's health.

When Titus Salt realised the council was unwilling to take action, he decided to move from Bradford. In 1850, Salt announced his plans to build a new industrial community called Saltaire at a nearby beauty spot on the banks of the River Aire. Saltaire, which was three miles from Bradford, took twenty years to build. At the centre of the village was Salt's textile mill. The mill was the largest and most modern in Europe. Noise in the factory was reduced by placing underground much of the shafting which drove the machinery. Large flues removed the dust and dirt from the factory floor. To ensure that the neighbourhood did not suffer from polluted air, the mill chimney was fitted with Rodda Smoke Burners.

Sam Kydd wrote in The Reynolds newspaper: "The site chosen for Saltaire is, in many ways, desirable. The scenery in the immediate neighbourhood is romantic, rural and beautiful. A better looking body of factory 'hands' than those in Saltaire I have not seen. They are far above the average of their class in Lancashire, and are considerably above the majority in Yorkshire."

At first Salt's 3,500 workers travelled to Saltaire from Bradford. However, during the next few years, 850 houses were built for his workers. Saltaire also had its own park, church, school, hospital, library and a whole range of different shops. The houses in Saltaire were far superior to those available in Bradford and other industrial towns. Fresh water was piped into each home from Saltaire's own 500,000 gallon reservoir. Gas was also laid on to provide lighting and heating. Unlike the people of Bradford, every family in Saltaire had its own outside lavatory. To encourage people to keep themselves clean, Salt also arranged for public baths and wash-houses to be built in Saltaire.

Titus Salt was also active in politics. Salt supported adult suffrage and did not believe that the 1832 Reform Act went far enough. In 1835 he was a founder of the Bradford Reform Association and publicly supported the Chartists. Disturbed by the growth of the Physical Force Chartists, Salt helped establish the United Reform Society, an attempt to unite middle and working class reformers.

Titus Salt was a severe critic of the 1834 Poor Law. He also supported the move to reduce working hours and was the first employer in the Bradford area to introduce the ten hour day. However, Salt held conservative views on some issues. He refused permission for his workers to join trade unions and disagreed with those like Richard Oastler and John Fielden who wanted Parliament to pass legislation on child labour. Salt employed young children in his factories and were totally opposed to the 1833 Factory Act that attempted to prevent children under the age of nine working in textile mills.

Salt gave his support to the Radical candidate in Bradford's parliamentary elections. However, at the request of the local Chamber of Commerce, Salt became a candidate in the 1859 General Election. Salt was elected but after two years in the House of Commons he resigned because of ill-health.

Titus Salt died on 29th December, 1876. Although he had been an extremely rich man, his family was horrified that his fortune was gone. It has been estimated that during his life he had given away over £500,000 to good causes. On his death The Bradford Observer commented: "Titus was perhaps the greatest captain of industry in England not only because he gathered thousands under him but also because, according to the light that was in him, he tried to care for all those thousands. We do not say that he succeeded in realising all his views or that it is possible to harmonise at present all relations between capital and labour. Upright in business, admirable in his private relations he came without seeking the honour to be admittedly the best representative of the employer class in this part of the country if not the whole kingdom."

On this day in 1893 Vera Brittain, the only daughter of Thomas Brittain (1864-1935), a wealthy paper manufacturer, and Edith Bervon (1868-1948), was born at Atherstone House, Newcastle-under-Lyme. Vera developed a close relationship with her brother, Edward Brittain. According to her biographer, Alan Bishop: "As they grew up, tended by a governess and servants, in an environment of conservative middle-class values, close supervision, and comparative isolation, brother and sister formed a companionship that was to be a dominant force in Vera's life." She later recalled: "As a child I wrote because it was as natural to me to write as to breathe, and before I could write I invented stories."

Thomas Brittain's two paper mills in Hanley and Cheddleton continued to prosper and in 1905 the family moved to the fashionable spa resort town, Buxton in Derbyshire. The Brittains lived at High Leigh House for two years before moving to an even larger house, Melrose in 1907. Vera was educated at home by a governess and then at a boarding school in Kingswood, where one of the teachers introduced her to the ideas of Dorothea Beale and Emily Davies. "Miss Heath Jones was an ardent though always discreet feminist. She often spoke to me of Dorothea Beale and Emily Davies, lent me books on the woman's movement, and even took me with one or two of the other senior girls in 1911 to what must have been a very mild and constitutional suffrage meeting at Tadworth village." Brittain was also deeply influence by reading Women and Labour by Olive Schreiner.

Vera wanted to go to university but her father believed that the main role of education was to prepare women for marriage. In 1912 she attended a course of Oxford University extension lectures given by the historian John Marriott. Despite the objections of her father, Brittain set about qualifying herself for admission to one of the recently established women's colleges.In 1913, her brother, Edward Brittain, introduced Vera to Roland Leighton, one of his friends from Uppingham School. Leighton, who had just won a place Merton College at Oxford University, encouraged her to go to university and in 1914 her father relented and Vera was allowed to go to Somerville College. He gave her a copy of Olive Schreiner's The Story of an African Farm. Roland told her that the main character, Lyndall, reminded him of her. Vera replied in a letter dated 3rd May 1914: "I think I am a little like Lyndall, and would probably be more so in her circumstances, uncovered by the thin veneer of polite social intercourse." Vera wrote in her diary that "he (Roland) seems even in a short acquaintance to share both my faults and my talents and my ideas in a way that I have never found anyone else to yet."

On the outbreak of the First World War Roland and Edward, together with their close friend Victor Richardson, immediately applied for commissions in the British Army. Vera wrote to Roland about his decision to take part in the war: "I don't know whether your feelings about war are those of a militarist or not; I always call myself a non-militarist, yet the raging of these elemental forces fascinates me, horribly but powerfully, as it does you. You find beauty in it too; certainly war seems to bring out all that is noble in human nature, but against that you can say it brings out all the barbarous too. But whether it is noble or barbarous I am quite sure that had I been a boy I should have gone off to take part in it long ago; indeed I have wasted many moments regretting that I am a girl. Women get all the dreariness of war and none of its exhilaration."

Edward Brittain introduced Vera to his friend, Geoffrey Thurlow. He was suffering from shellshock after experiencing heavy bombardment at Ypres in February 1915. He was sent back to England and was at hospital at Fishmongers' Hall when he was visited by Vera. She wrote to Roland Leighton on 11th October 1915: "I liked Thurlow so much. Whatever Edward's failings, I must say he has an admirable faculty for choosing his friends well... But seeing Thurlow for a short time made me feel rather sad, for the nicer such people as he are, the more they serve to emphasize in some indirect way, the fact of your immense superiority over the very best of them!"

By the end of her first year at Somerville College she decided it was her duty to abandon her academic career to serve her country. During the summer of 1915 she worked at the Devonshire Hospital in Buxton, as a nursing assistant, tending wounded soldiers. On 28th June 1915 she wrote to Roland pointing out: "I can honestly say I love nursing, even after only two days. It is surprising how things that would be horrid or dull if one had to do them at home quite cease to be so when one is in hospital. Even dusting a ward is an inspiration. It does not make me half so tired as I thought it would either... The majority of cases are those of people who have got rheumatism resulting from wounds. Very few come straight from the trenches, it is too far, but go to another hospital first. One man in my ward had six operations before coming and is still almost helpless."

Vera applied to join the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) as a nurse and in November 1915 was posted to the First London General Hospital at Camberwell. Vera found this a traumatic experience. On 7th November 1915 she wrote to Roland Leighton: "I have only one wish in life now and that is for the ending of the war. I wonder how much really all you have seen and done has changed you. Personally, after seeing some of the dreadful things I have to see here, I feel I shall never be the same person again, and wonder if, when the war does end, I shall have forgotten how to laugh... One day last week I came away from a really terrible amputation dressing I had been assisting at - it was the first after the operation - with my hands covered with blood and my mind full of a passionate fury at the wickedness of war, and I wished I had never been born."

She found dealing with the parents of wounded soldiers particularly difficult: "Today is visiting day, and the parents of a boy of 20 who looks and behaves like 16 are coming all the way from South Wales to see him. He has lost one eye, had his head trepanned and has fourteen other wounds, and they haven't seen him since he went to the front. He is the most battered little object you ever saw. I dread watching them see him for the first time."

Vera Brittain wrote in her diary: "Sometimes in the middle of the night we have to turn people out of bed and make them sleep on the floor to make room for the more seriously ill ones who have come down from the line. We have heaps of gassed cases at present: there are 10 in this ward alone. I wish those people who write so glibly about this being a holy war, and the orators who talk so much about going on no matter how long the war lasts and what it may mean, could see a case - to say nothing of 10 cases of mustard gas in its early stages - could see the poor things all burnt and blistered all over with great suppurating blisters, with blind eyes - sometimes temporally, some times permanently - all sticky and stuck together, and always fighting for breath, their voices a whisper, saying their throats are closing and they know they are going to choke."

Vera became engaged to Roland Leighton, while he was on leave in August 1915. On his return to France he was stationed in trenches near Hebuterne, north of Albert. On the 26th November 1915 he wrote a letter to Vera that highlighted his disillusionment with the war. "It all seems such a waste of youth, such a desecration of all that is born for poetry and beauty. And if one does not even get a letter occasionally from someone who despite his shortcomings perhaps understands and sympathises it must make it all the worse... until one may possibly wonder whether it would not have been better to have met him at all or at any rate until afterwards. I sometimes wish for your sake that it had happened that way."

On the night of 22nd December 1915 he was ordered to repair the barbed wire in front of his trenches. It was a moonlit night with the Germans only a hundred yards away and Roland Leighton was shot by a sniper. His last words were: "They got me in the stomach, and it's bad." He died of his wounds at the military hospital at Louvencourt on 23rd December 1915. He is buried in the military cemetery near Doullens.

In her autobiography Vera recalled visiting Roland's family home in Hassocks. "I arrived at the cottage that morning to find his mother and sister standing in helpless distress in the midst of his returned kit, which was lying, just opened, all over the floor. The garments sent back included the outfit that he had been wearing when he was hit. I wondered, and I wonder still, why it was thought necessary to return such relics - the tunic torn back and front by the bullet, a khaki vest dark and stiff with blood, and a pair of blood-stained breeches slit open at the top by someone obviously in a violent hurry. Those gruesome rages made me realise, as I had never realised before, all that France really meant."

On 3rd January 1916, Vera returned to First London General Hospital at Camberwell. In his book, Letters From a Lost Generation (1998), Alan Bishop argued that "nursing proved an intolerable strain while her grief for Roland was still so raw on the support" of Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow, who were both recovering in military hospitals.

Edward Brittain arrived on the Western Front at the beginning of 1916. On 27th February he wrote to his sister, Vera Brittain. "Ordinary risks of stray shots or ricochets off a sandbag or the chance of getting hit when you look over the parapet in the night time - you hardly ever do in the day time but use periscopes - are daily to be encountered. But far the most dangerous thing is going out on patrol in No Man's Land. You take bombs in case you should meet a hostile patrol, but you might be surrounded, you might be seen especially if you go very close to their line and anyhow. Very lights are always being sent up and they make night into day so you have to keep down and quite still, and you might get almost on top of their listening post if you are not sure where it is."

On 8th January 1916 Victor Richardson suggested a meeting with Vera. "May I come and see you on Wednesday afternoon? I suggest this next Wednesday, because I am on guard at one of the Arsenal entrances during the week, and as it is not an important position I could leave my coadjutor in charge for the afternoon, and disappear - without leave..... Of course if you do not feel inclined to see people I shall quite understand. If I do not hear from you I shall assume this to be the case." Vera agreed to the meeting, as she told her brother, Edward Brittain: "I had tea with Victor on Wednesday. Of course we talked of Roland the whole time."

Vera wrote to her brother on 23rd February about her new friend, Geoffrey Thurlow: "I saw that Thurlow had been wounded - I suppose in the recent fighting at Ypres. I have almost loved him since his little letter to me after Roland died, and I can't tell you how anxiously I hope that he is not badly hurt." Vera went to visit Geoffrey on 27th February. Later that day she wrote to her brother about his condition: "I have just been to see Thurlow at Fishmongers' Hall Hospital, London Bridge. He is only very slightly wounded on the left side of his face; fortunately his eyes, nose and mouth are quite untouched. In fact he says he won't even have a scar left, and the wound is healing with a depressing rapidity.... He was apparently wounded in the bombardment, before all the trench fighting began. He thinks hardly any of his battalion are left now."

Vera told Edward Brittain that Thurlow was suffering from the consequences of serving on the front-line: "Thurlow was... sitting before a gas stove, with a green dressing gown on and a brown blanket over his knees. He seems to feel the cold a great deal, which must be owing to the shock, and also for the same reason his nerves are very bad, so he has been given two months sick leave."

Thurlow told Vera that he was keen to return to France. "Of course he doesn't want to go back a bit, but since he has to go, he's got the same feeling as he had before, that he wants to go out quickly and get it over. He says he finds the anticipation so much worse than the things themselves, whatever they are. He says he is not a bit of a success out there because he is so afraid of being afraid, and he hates the way all his men's eyes are fixed on him when anything big is on, partly to see how he will take it, partly because they are afraid of anything happening to him. He says he objects to war on principle, and is a non-militarist very strongly at heart. I think it was very brave of him to join almost at once as he did... It is easy to see he is suffering from shock; he looks rather a ghost now he is sitting up, talks even more jerkily than before, and works his fingers about nervously while he is talking."

Vera found nursing badly wounded men very difficult: "He (Victor Richardson) has been near death, I know, but he hasn't seen men with mutilations such as I have, though he may have heard a lot about them; I must admit that when, as I am doing at present, I have to deal with men who have only half a face left and the other side bashed in out of recognition, or part of their skull torn away, or both feet off, or an arm blown off at the shoulder."

Edward took part in the Battle of the Somme on 1st July 1916. The author of Letters From a Lost Generation (1998) has pointed out: "While his company was waiting to go over, the wounded from an earlier part of the attack began to crowd into the trenches. Then part of the regiment in front began to retreat, throwing Edward's men into a panic. He had to return to the trenches twice to exhort them to follow him over the parapet. About ninety yards along No-Man's-Land, Edward was hit by a bullet through his thigh. He fell down and crawled into a shell hole. Soon afterwards a shell burst close to him and a splinter from it went through his left arm. The pain was so great that for the first time he lost his nerve and cried out. After about an hour and a half, he noticed that the machine-gun fire was slackening, and started a horrifying crawl back through the dead and wounded to the safety of the British trenches."

Edward Brittain was sent to First London General Hospital at Camberwell where his sister was working as a nurse. According to Alan Bishop: "After receiving permission from his Matron to visit him, Vera hurried to Edward's bedside. He was struggling to eat breakfast with only one hand, his left arm was stiff and bandaged, but he appeared happy and relieved. Edward would remain in the hospital for three weeks before beginning a prolonged period of convalescent leave." On 24th August it was announced that Brittain had been awarded the Military Cross.

On 24th September, 1916, Vera received news that she was being posted to Malta. Her brother, Edward Brittain wrote on the 5th October: "The night of the day you left London the Zeppelins dropped 4 bombs at Purley somewhere up that hill where we walked one afternoon when I was still bad only about 600yds from the house but it did no damage. A foolish woman came out into the road and therefore received some shrapnel in one eye from one of our own guns but otherwise there was no damage except windows and a pillar box."

Vera Brittain continued to communicate with Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow. Richardson, who was a member of the 9th King's Royal Rifles was stationed on a quiet sector of the Western Front: "I have so far come across nothing more gruesome than a few very dead Frenchman in No Man's Land, so cannot give you very thrilling descriptions. The thing one appreciates in the life here more than anything else is the truly charming spirit of good fellowship and freedom from pettiness that prevails everywhere." Thurlow wrote on 18th November 1916: "Since my last letter much has happened - we have been to the war again and the weather treated us abominably: however our battalion did well taking an important Hun trench - we didn't go over the top but had to clean up and hang on to the trench. Luckily we had no officer casualties though there were many among the men. But as our number of officers is at present the irreducible minimum perhaps this accounts for it."

Edward Brittain received his Military Cross from George V on 16th December 1916. In a letter to Vera he wrote: "We were instructed what to do by a Colonel who I believe is the King's special private secretary and then the show started. One by one we walked into an adjoining room about 6 paces - halt - left turn - bow - 2 paces forward - King pins on cross - shake hands - pace back - bow - right turn and slope off by another door... The King spoke to a few of us including me; he said "I hope you have quite recovered from your wound", to which I replied "Very nearly thank you, Sir", and then went out with the cross in my pocket in a case. I met Mother just outside and we went off towards Victoria thinking we had quite escaped all the photographers, but unfortunately one beast from the Daily Mirror saw us and took us, but luckily it does not seem to have come out well as it is rather bad form to have your photo in a cheap rag if avoidable."

On 20th February 1917, Vera wrote a very personal letter to Edward: "But where you and I are concerned, sex by itself doesn't interest us unless it is united with brains and personality; in fact we rather think of the latter first, and the person's sex afterwards... I think very probably that older women will appeal to you much more than younger ones, as they do me. This means that you will probably have to wait a good many years before you find anyone you could wish to marry, but I don't think this need worry you, for there is plenty of time, and very often people who wait get something well worth waiting for."

In a letter to Edward Brittain on 2nd April 1917, Vera reported that some of the staff had been posted to Salonika. "I wish they would send some of us.... I would volunteer like a shot. Not because the city of malaria and mosquitoes and air-raids and odours suggests many attractions, but because this wandering, unsettled, indefinite sort of life makes one yearn to taste as much as one can of what the war has placed within human experience."

Victor Richardson was badly wounded during an attack at Arras on 9th April 1917. Vera wrote to her mother, Edith Brittain: "There really does not seem much point in writing anything until I hear further news of Victor, for I cannot think of anything else... I knew he was destined for some great action, even as I knew beforehand about Edward, for only about a week ago I had a most pathetic letter from him - a virtual farewell. It is dreadful to be so far away and all among strangers.... Poor Edward! What a bad time the Three Musketeers have had!"

Richardson was sent back to London where he received specialist treatment at a hospital in Chelsea. Edward Brittain, visited him in hospital, and then wrote to Vera, about his condition: "It is not known yet whether Victor will die or not, but his left eye was removed in France and the specialist who saw him thinks it is almost certain that the sight of the right eye has gone too... The bullet - probably from a machine-gun - went in just behind the left eye and went very slightly upwards but not I'm afraid enough to clear the right eye; the bullet is not yet out though very close to the right edge of the temple; it is expected that it will work through of its own accord... We are told that he may remain in his present condition for a week. I don't think he will die suddenly but of course the brain must be injured and it depends upon how bad the injury is. I am inclined to think it would be better that he should die; I would far rather die myself than lose all that we have most dearly loved, but I think we hardly bargained for this. Sight is really a more precious gift than life."

Geoffrey Thurlow was killed in action at Monchy-le-Preux on 23rd April 1917. Three days later, Captain J. W. Daniel, wrote to Edward Brittain, about Thurlow's death: "The hun had got us held up and the leading battalions of the Brigade had failed to get their objective. The battalion came up in close support through a very heavy barrage, but managed to get into the trench - of which the Boshe still held a part... I sent a message to Geoffrey to push along the trench and find out if possible what was happening on the right. the trench was in a bad condition and rather congested, so he got out on the top. Unfortunately the Boche snipers were very active and he was soon hit through the lungs. Everything was done to make him as comfortable as possible, but he died lying on a stretcher about fifteen minutes later."

Edward wrote to Vera about Thurlow: "Always a splendid friend with a splendid heart and a man who won't be forgotten by you or me however long or short a time we may live. Dear child, there is no more to say; we have lost almost all there was to lose and what have we gained? Truly as you say has patriotism worn very very threadbare."

Vera Brittain replied: "I can't tell you how I shall miss Geoffrey - I think he meant more to me that anyone after Roland and you. as for you I dare not think how lonely you must feel with him dead and Victor perhaps worse, for it makes me too impatient of the time that must elapse before I can see you - I may not even be able to start for two or three weeks. Geoffrey and I had become very friendly indeed in letters of late, and used to write at least once a week... After Roland he was the straightest, soundest, most upright and idealistic person I have ever known."

Vera decided to return home after the death of Geoffrey Thurlow and the serious injuries suffered by Victor Richardson. She told her brother: "As soon as the cable came saying that Geoffrey was killed, only a few hours after the one saying that Victor was hopelessly blind, I knew I must come home. It will be easier to explain when I see you, also - perhaps - to consult you about something I can't possibly discuss in a letter. Anyone could take my place here, but I know that nobody else could take the place that I could fill just now at home."

Edward Brittain went to visit Victor and on 7th May he told his sister: "He was told last Wednesday that he will probably never see again, but he is marvellously cheerful.... He is perfectly sensible in every way and I don't think there is the very least doubt that he will live. He said that the last few days had been rather bitter. He hasn't given up hope himself about his sight."

Vera arrived in London on 28th May 1917. The next ten days she spent at Victor's bedside. As Alan Bishop points out: "His mental faculties appeared to be in no way impaired. On 8 June, however, there was a sudden change in his condition. In the middle of the night he experienced a miniature explosion in the head, and subsequently became very distressed and disoriented. By the time his family reached the hospital Victor had become delirious." Victor Richardson died of a cerebral abscess on 9th June, 1917 and is buried in Hove. He was awarded the Military Cross posthumously.

Edward returned to the Western Front in June 1917. Vera decided she wanted to be as close to her brother as possible and in July she returned to duty with the Voluntary Aid Detachment and requested a posting to France. On 30th June 1917 Edward wrote to Vera: "The unexpected has happened again and I am in for another July 1st (Battle of the Somme)... You know that, as I promised, I will try to come back if I am killed. It is all very sudden and it is bad luck that I am here in time, but still it must be. All the love there is in life or death."

On 3th August 1917, Vera joined a small draft of nurses who were being sent out to the 24th General Hospital at Étaples. She wrote to her mother on 5th August: "I arrived here yesterday afternoon; the hospital is about a mile out of the town, on the side of the hill, in a large clearing surrounded on three sides by woods... The hospital is frantically busy and we were very much welcomed.... You will be surprised to hear that at present I am nursing German prisoners. My ward is entirely reserved for the most acute German surgical cases... The majority are more or less dying; never, even at the 1st London during the Somme push, have I seen such dreadful wounds. Consequently they are all too ill to be aggressive, and one forgets that they are the enemy and can only remember that they are suffering human beings."

Vera had to deal with men suffering from mustard gas attacks. She wrote to her mother on 5th December 1917: "We have heaps of gassed cases at present who came in a day or two ago; there are ten in this ward alone. I wish those people who write so glibly about this being a holy war and the orators who talk so much about going on no matter how long the war lasts and what it may mean, could see a case - to say nothing of ten cases - of mustard gas in its early stages - could see the poor things burnt and blistered all over with great mustard coloured suppurating blisters, with blinded eyes - sometimes temporally, sometimes permanently - all sticky and stuck together, and always fighting for breath, with voices a mere whisper, saying that their throats are closing and they know they will choke. The only thing one can say it that such severe cases don't last long; either they die soon or else improve - usually the former; they certainly don't reach England in the state we have them here, and yet people persist in saying that God made War, when there are such inventions of the Devil about."

In her autobiography, Testament of Youth (1933), Vera recorded: "Sometimes in the middle of the night we have to turn people out of bed and make them sleep on the floor to make room for the more seriously ill ones who have come down from the line.... The strain is very, very great. The enemy is within shelling distance - refugee sisters crowding in with nerves all awry - bright moonlight, and aeroplanes carrying machine guns - ambulance trains jolting into the siding, all day, all night - gassed men on stretchers clawing the air - dying men reeking with mud and foul green stained bandages, shrieking and writhing in a grotesque travesty of manhood - dead men with fixed empty eyes and shiny yellow faces."

In September 1917 Edward Brittain took part in a major offensive. He wrote to Vera on the 23rd: "We came out (of the front-line) last night... had about 50 casualties including one officer in the company - the best officer of course. I ought to have been slain myself heaps of times but I seem to be here still. Harrison has arrived back and it is quite a relief to hand the company over for a bit."

The following month Edward was sent to Ypres for the offensive at Passchendaele. He wrote to Vera on 7th October 1917: "My leave seems to have been stopped for the present for some reason or other and also we are probably going up to Ypres again tonight to provide working-parties etc. which is as unexpected as it is objectionable; it is filthy weather, cold and pouring with rain and I have just caught a bad cold and so am not particularly pleased with life."

In November 1917 Edward Brittain and the 11th Sherwood Foresters were posted to the Italian Front in the Alps above Vicenza, following the humiliating rout of the Italian Army at Caporetto. On 15th November 1917, he wrote to Vera: "We marched through the city yesterday - it is old, picturesque and rather sleepy with narrow streets and pungent smells; we have been accorded a most hearty reception all the way and have been presented with anything from bottles of so-called phiz, to manifestos issued by mayors of towns; flowers and postcards were the most frequent tributes."

While she was in Étaples Vera received a letter from her father informing her that her mother had suffered a complete breakdown and entered a nursing home in Mayfair, and that it was her duty to leave France immediately and return home to Kensington. Vera arrived back in England in April 1918 and arranged for her mother to return home. According to the author of Letters From a Lost Generation (1998): "Vera... took charge of the household. But it was with a strong air of resentment that she tried to reaccustom herself to the dull monotony of civilian life."

On 15th June, 1918, the Austrian Army launched a surprise attack with a heavy bombardment of the British front-line along the bottom of the San Sisto Ridge. Edward Brittain led his men in a counter-offensive and had regained the lost positions, but soon afterwards, he was shot through the head by a sniper and had died instantaneously. He was buried with four other officers in the small cemetery at Granezza.

Alan Bishop points out that his commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Hudson, had ordered an investigation into Brittain's homosexuality: "Shortly before the action in which he was killed, Edward had been faced with an enquiry and, in all probability, a court martial when his battalion came out of the line, because of his involvement with men in his company. It remains a possibility that, faced with the disgrace of a court martial, Edward went into battle deliberately seeking to be killed."

After the Armistice Vera returned to Somerville College. She later recalled: "At Somerville the news of my intention to change my School was received without enthusiasm; in English I had been regarded as a probable First, but in the field of History I had forgotten even such information as I had once derived from Miss Heath Jones's political and religious teaching... I never regretted the decision, for in studying international relations, and the great diplomatic agreements of the nineteenth century, I discovered that human nature does change, does learn to hate oppression, to deprecate the spirit of revenge, to be revolted by acts of cruelty, and at last to embody these changes of heart." She added that she hoped that studing history would help her "understand how the whole calamity (of the war) had happened, to know why it had been possible for me and my contemporaries, through our own ignorance and others' ingenuity, to be used, hypnotised and slaughtered".

At Oxford University Vera met Winifred Holtby. She explained in her autobiography, Testament of Youth (1933): "I was staring gloomily at the Oxford engravings and photographs graphs of the Dolomites which clustered together so companionably upon the Dean's study wall, when Winifred Holtby burst suddenly in upon this morose atmosphere of ruminant lethargy. Superbly tall, and vigorous as the young Diana with her long straight limbs and her golden hair, her vitality smote with the effect of a blow upon my jaded nerves. Only too well aware that I had lost that youth and energy for ever, I found myself furiously resenting its possessor. Obstinately disregarding the strong-featured, sensitive face and the eager, shining blue eyes, I felt quite triumphant because - having returned from France less than a month before - she didn't appear to have read any of the books which the Dean had suggested as indispensable introductions to our Period."

Vera and Winifred graduated together in 1921 and they moved to London where they hoped to establish themselves as writers. Vera's first two novels, The Dark Tide (1923) and Not Without Honour (1925) sold badly and were ignored by the critics. However, Winifred had more success with Anderby Wold (1923) and The Crowded Street (1924). Vera had more success with her journalism and in 1920s wrote for the feminist journal, Time and Tide. Vera also published two books on the role of women, Women's Work in Modern Britain (1928) and Halcyon or the Future of Monogamy (1929).

In June 1925 Vera Brittain married the academic, George Edward Catlin. As Mark Bostridge has pointed out: "When Brittain and Catlin set up home in London after their marriage, Holtby joined them as the third member of the household. Catlin never overcame his resentment at his wife's friendship with the woman Vera described as her second self. He knew, in spite of all the gossip to the contrary, that the Brittain-Holtby relationship had never been a lesbian one, but its closeness still rankled."

Vera and her husband moved to the United States when her husband became a a professor at Cornell University. Vera found it difficult to settle in America and after the birth of her two children, John (1927) and Shirley (1930) she moved back to England where she lived with Winifred Holtby. Vera's daughter, Shirley Williams, later wrote: "Some critics and commentators have suggested that their relationship must have been a lesbian one. My mother deeply resented this. She felt that it was inspired by a subtle anti-feminism to the effect that women could never be real friends unless there was a sexual motivation, while the friendships of men had been celebrated in literature from classical times. My mother was instinctively heterosexual. But as a famous woman author holding progressive opinions, she became an icon to feminists and in particular to lesbian feminists." However, Vera's husband, George Edward Catlin, did not approve of the relationship. He wrote later: "You preferred her to me. It humiliated me and ate me up.

In her first volume of autobiography, Testament of Youth (1933) Brittain wrote about her struggle for education and her experiences as a nurse during the First World War. It also told of her relationship with her brother, Edward Brittain, and her love of Roland Leighton, Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow. The novelist, Margaret Storm Jameson, reviewed the book in the Sunday Times and said that as a representation of war from a woman's perspective "makes it unforgettable". It was an immediate bestseller in Britain and the United States.

Vera Brittain became a full-time writer. In her autobiography, Shirley Williams wrote: "Determinedly professional, my mother was at work in her study by 10am, after reading the newspapers and the morning's letters, sorting out the shopping lists and paying the bills. Her study was a sacred place, of blotters and pens in black-and-gold stands, of carefully ranged notepaper and envelopes, and of manuscripts composed in her neat, rounded script. Only death, war or a serious accident would justify interrupting her there."

On 7th July, 1934, the British Union of Fascists held a large rally at Olympia. About 500 anti-fascists including Vera Brittain, Margaret Storm Jameson, Richard Sheppard and Aldous Huxley, managed to get inside the hall. When they began heckling Oswald Mosley they were attacked by 1,000 black-shirted stewards. Several of the protesters were badly beaten by the fascists. Jameson argued in The Daily Telegraph: "A young woman carried past me by five Blackshirts, her clothes half torn off and her mouth and nose closed by the large hand of one; her head was forced back by the pressure and she must have been in considerable pain. I mention her especially since I have seen a reference to the delicacy with which women interrupters were left to women Blackshirts. This is merely untrue... Why train decent young men to indulge in such peculiarly nasty brutality? There was a public outcry about this violence and Lord Rothermere and his Daily Mail withdrew its support of the BUF. Over the next few months membership went into decline.

In the early 1930s Winifred Holtby began to suffer with high-blood-pressure, recurrent headaches and bouts of lassitude. Eventually she was diagnosed as suffering from Bright's Disease. Her doctor told her that she probably only had two years to live. Aware she was dying, Winifred put all her remaining energy into what became her most important book, South Riding.

Vera Brittain later recalled that she asked Harry Pearson to tell "Winifred he loved her and always had; that he'd like to marry her when she was better". She added that on 28th September, 1935: "At about three o'clock Hilda Reid rang up to say that Dr. Obermer had been round to the home and had already put Winifred under morphia; she was now unconscious and would never be permitted to come back to consciousness again. Later I learnt that Dr. Obermer did this because after Harry had been with Winifred she was so happy and excited that he feared a violent convulsion for her, with physical pain and mental anguish; and that he thought it best to let her go out on that moment of happiness, with the cruel realization that what she was hoping could never be fulfilled."

The following day Vera went to visit Winifred at the nursing home at 23 Devonshire Street in Marylebone: "Shortly after six o'clock I realised that she was breathing more shallowly, while her pulse was slower and weaker. After almost a quarter of an hour her pulse, which I was holding, had almost stopped, and her breathing seemed to come from her throat only... It was strange, incredible, after all the years of our friendship and all that we had shared together, to feel her life flickering out under my hand. Suddenly her pulse stopped; she had given two or three deeper breaths and then these ceased and I thought she had stopped breathing too; but after a moment came one final, lingering sigh, and then everything was at an end."

Winifred Holtby died on 29th September, 1935. Vera Brittain was Winifred's literary executor, and was determined to make sure South Riding was published. However, as Mark Bostridge has pointed out: "The major obstacle she faced was the indomitable figure of Holtby's mother, Alice, the first woman alderman of the East Riding. She feared that her daughter's depiction of local government, allied to the vein of satire and puckish mischief familiar from her earlier books, might expose her own job to criticism and ridicule... Alice Holtby remained obdurate in her opposition to the book's publication, forcing Brittain to adopt a strategy of mild subterfuge, negotiating the uncorrected typescript through probate in order to have the novel ready for publication by Collins in the spring of 1936."

In 1935 Vera's father committed suicide. Grief-stricken by the deaths of Winifred and her father, Vera struggled to complete her own finest novel, Honourable Estate: a Novel of Transition (1936). According to her biographer, Alan Bishop, it was a "long, ambitious, feminist, pacifist, a family saga based on the recent history of the Brittain and Catlin families. It greatly disturbed George Catlin for it drew particularly on the diary of his mother, who had abandoned son and husband."

Brittain also became friendly with Richard Sheppard, a canon of St. Paul's Cathedral. He had been an army chaplain during the First World War. A committed pacifist, he was concerned by the failure of the major nations to agree to international disarmament and on 16th October 1934, he had a letter published in the Manchester Guardian inviting men to send him a postcard giving their undertaking to "renounce war and never again to support another." Within two days 2,500 men responded and over the next few weeks around 30,000 pledged their support for Sheppard's campaign.

In July 1935 Sheppard chaired a meeting of 7,000 members of his new organization at the Albert Hall in London. Eventually named the Peace Pledge Union (PPU), it achieved 100,000 members over the next few months. The organization now included other prominent religious, political and literary figures including Brittain, Arthur Ponsonby, George Lansbury, Margaret Storm Jameson, Wilfred Wellock, Max Plowman, Maude Royden, Frank P. Crozier, Alfred Salter, Ada Salter, Siegfried Sassoon, Donald Soper, Aldous Huxley, Laurence Housman and Bertrand Russell.

In the 1930s Brittain became a pacifist and in 1934 supported Richard Sheppard and his Peace Pledge Union and was one of its leaders during the Second World War. From September 1939 she began publishing Letters to Peace Lovers, a small journal that expressed her views on the war. This made her extremely unpopular as the journal criticised the government for bombing urban areas in Nazi Germany.

Vera wrote about her relationship with Winifred Holtby in her book Testament of Friendship (1940). In her books, England's Hour: an Autobiography (1941) and Humiliation with Honour (1943), Brittain attempted to explain her pacifism in her book Humiliation with Honour. This was followed by Seeds of Chaos, an attack on the government's policy of area bombing.

Her final two novels, Account Rendered (1945) and Born 1925: a Novel of Youth (1948), both sold badly and as a result she turned away from fiction. Other books by Brittain included a history of the women's movement, Lady into Women (1953), a second volume of autobiography, Testament of Experience (1957), Women at Oxford (1960), Pethick-Lawrence: a Portrait (1963), a biography of peace-campaigner, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, The Rebel Passion: a Short History of some Pioneer Peacemakers (1964) and Radclyffe Hall: a Case of Obscenity? (1968), an account of the lesbian novelist, Radclyffe Hall.

A strong opponent of nuclear weapons, in 1957 Brittain joined with Kingsley Martin, J. B. Priestley, Bertrand Russell, Fenner Brockway, Victor Gollancz, Richard Acland, A. J. P. Taylor, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot to form the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

Vera Brittain remained active in the peace movement until her death on 29th March 1970 in a nursing home in Wimbledon. In accordance with her last wishes, Vera's ashes were scattered over Edward's grave at the cemetery of Granezza, in September 1970.

On this day in 1806 Charles Lennox, the 3rd Duke of Richmond died. Lennox, the son of the 2nd Duke of Richmond, was born on 22nd February, 1735. After an education at Westminster School and entered the British army. Lennox served in several expeditions and distinguished himself in the Battle of Minden. He had reached the rank of colonel when he succeeded his father as the third Duke of Richmond on 6th August, 1750. He first took his seat in the House of Lords on 15th March 1756.

In 1760 the Duke of Richmond was was appointed a lord of the bedchamber, but shortly afterwards quarreled with George III and resigned from office. Richmond became lord-lieutenant of Sussex and in 1766 was appointed by the Marquis of Rockingham as Secretary of State for the Southern Department. Richmond retired from office when the Earl of Chatham replaced Rockingham as Prime Minister.

Richmond was a strong critic of Lord North's American policy. In December 1775, he declared in the House of Lords that the resistance of the colonists was "neither treason nor rebellion, but it is perfectly justifiable in every possible political and moral sense." It was during a speech made by Richmond in the House of Lords calling for the withdrawal of British troops from America that the Earl of Chatham collapsed and died.

Richmond also joined the campaign to remove the causes of Irish discontent. He opposed the Tory policy of an Act of Union and argued that he was in favour of an "union but not an union of legislature, but an union of hearts, hands, of affections and interests". Richmond retained his hostility to George III and in December 1779 he called for a reduction in the spending on the monarchy and described the civil list as "lavish and wasteful to a shameful degree".

In 1774 Richmond read a pamphlet that his friend, Granville Sharp, had written, called The Natural Right of People to Share in the Legislature (1774). This created an interest in parliamentary reform, and over the next few years Richmond read several pamphlets on the subject including The Nature of Civil Liberty (1776) by Richard Price and Take Your Choice (1777) by Major John Cartwright.

By the end of the 1770s most Whigs supported parliamentary reform. This included John Wilkes and Charles Fox. However, by this time, Richmond was the most radical in his party, supporting both annual parliaments and manhood suffrage. Richmond was now convinced that without parliamentary reform, revolution was inevitable.

On the 3rd June 1780 the Duke of Richmond decided to push the Whigs into action by introducing his own proposals for the reform of Parliament. His bill included plans for annual parliaments, manhood suffrage and 558 equally populous electoral districts. Richmond found very little support for his radical proposals and his bill was rejected without a vote.

The Marquis of Rockingham, the leader of the Whigs, died on 1st July 1782. Richmond attempted to become leader of the party, but his radical views on parliamentary reform ensured that he was defeated by the Duke of Portland. In April 1783 William Pitt invited Richmond to join his coalition ministry. He initially refused, but Richmond eventually joined the government and after that date showed little interest in the subject of parliamentary reform.

In 1794 Thomas Hardy and John Horne Tooke of the London Corresponding Society, were charged with high treason. Hardy and Tooke argued that were not guilty of treason as the Corresponding Society had been constituted solely to carry out the reforms proposed by the Duke of Richmond's Reform Bill of 1780. Richmond was called upon to testify at their trial where he was forced to admit that in 1780 he had supported the same measures that had resulted in Hardy and Tooke being charged with high treason. Richmond was severely embarrassed by having to publicly acknowledge the radical views he had held before becoming a member of the government. Tooke and Hardy were acquitted and two months later the Duke of Richmond was sacked from the cabinet.

This brought an end to the Richmond's involvement in government. He retired to Goodwood where he supervised the planning and construction of a race track near his home. From 1796 to 1800 Richmond only appeared in the House of Lords on two occasions. The Duke of Richmond spoke for the last time in the House of Lords on 25th June 1804. He died at Goodwood, Sussex, on 29th December, 1806 and afterwards was buried in Chichester Cathedral.

On this day in 1809 William Ewart Gladstone, the fourth son of Sir John Gladstone, was born in Liverpool on 29th December, 1809. Gladstone was a MP and a successful merchant. The Gladstones were a rich family, their fortune based on transatlantic corn and tobacco trade and on the slave-labour sugar plantations they owned in the West Indies.

John Gladstone was a devout Presbyterian, but there was no Scottish church in Liverpool and in 1792 he and other Scots living in the city organised the building of a Scottish chapel and the Caledonian School opposite it for the education of their children.

Gladstone was therefore born into an evangelical family who held strong religious beliefs. He later wrote: "The Evangelical movement... did not ally itself with literature, art and general cultivation; but it harmonized well with the money-getting pursuits."

William was educated at Eton and Christ College. At the Oxford Union Debating Society Gladstone developed a reputation as a fine orator. After one speech he made on 14th November 1830, a fellow student, Charles Wordsworth, described it as "the most splendid speech, out and out, that was ever heard in our Society." Francis Doyle added: "When he sat down, we all of us felt that an epoch in our lives had occurred."

At that time the Tories were the dominant force in the House of Commons and they were strongly opposed to increasing the number of people who could vote. However, in November, 1830, Earl Grey, a Whig, became Prime Minister. Grey explained to William IV that he wanted to introduce proposals that would get rid of some of the rotten boroughs. Grey also planned to give Britain's fast growing industrial towns such as Manchester, Birmingham, Bradford and Leeds, representation in the House of Commons.

Gladstone denounced Whig proposals for parliamentary reform. "My youthful mind and imagination were impressed with some idle and futile fears which still bewilder and distract the mature mind". The 1832 Reform Act was eventually passed. "The overall effect of the Reform Act was to increase the number of voters by about 50 per cent as it added some 217,000 to an electorate of 435,000 in England and Wales. But 650,000 electors in a population of 14 million were a small minority." Gladstone was disappointed by this legislation. He later pointed out that "while I do not think that the general tendencies of my mind were, in the time of my youth, illiberal, there was to my eyes an element of the anti-Christ in the Reform Act."

In 1832, the Duke of Newcastle was looking for a Tory candidate for his Newark constituency. Although a nomination borough, Newark had been spared in the 1832 Reform Act. Sir John Gladstone was a friend of the Duke and suggested his son would make a good MP. Gladstone was selected as a candidate and although he lost some votes because his father was a wealthy slave-owner, he won the seat in the 1832 General Election.

Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. This act gave all slaves in the British Empire their freedom. Gladstone's father, who owned several large plantations in Jamaica and Guyana, expelled most African workers from his estates and imported large numbers of indebted Indian indentured-servants. They were paid no wages, the repayment of their debts being deemed sufficient, and worked under conditions that continued to resemble slavery in everything except name. Gladstone eventually received £106,769 (modern equivalent £83m), in compensation.

Two years after entering the House of Commons as MP for Newark, Sir Robert Peel, the Prime Minister, appointed William Gladstone as his junior lord of the Treasury. The following year he was promoted to under-secretary for the colonies. Gladstone lost office when Peel resigned in 1835 but returned to the government when the Whigs were forced out of power in August, 1841.

Peel appointed William Ewart Gladstone as vice-president of the board of trade. Although he was only just over 30 years of age, he was bitterly disappointed as he expected a place in the Cabinet. However, he was praised by the way he carried out his duties. James Graham, the Home Secretary, noted that "Gladstone could do in four hours what it took any other man sixteen to do and that he nonetheless worked sixteen hours a day".

On this day in 1878 Henry Vincent died. Vincent, the son of Thomas Vincent, a goldsmith, was born at High Holban on 10th May, 1813. Thomas Vincent's business failed when Henry was a boy and the family moved to Hull.

In 1828 Henry became an apprentice printer and soon afterwards joined a Tom Paine discussion group. Henry Vincent was particularly influenced by Paine's ideas on universal suffrage and welfare benefits.

After completing his apprenticeship in 1833, Vincent moved back to London where he obtained employment as a printer. He continued to be active in politics and in 1836 he joined the recently formed London Working Mens' Association. By 1837 he had developed a reputation as one of the best orators involved in the promotion of universal suffrage. In the summer of 1837 Vincent and John Cleave went on a speaking tour of Northern England and helped establish Working Mens' Associations in Hull, Leeds, Bradford, Halifax and Huddersfield.

In 1838 Vincent concentrated his efforts in recruiting supporters for the Charter in the West Country and South Wales. He was not always welcomed by local people and in Devizes he was attacked and knocked unconscious. However, he was very successful in persuading people in mining communities to join the movement.

The authorities became concerned about Vincent's ability to convert working people to the ideas of universal suffrage. They were particularly worried by his warnings that the Chartists might be forced to use Physical Force to win the vote. Vincent was followed around by government spies and in May 1838 he was arrested for making inflammatory speeches. On 2nd August he was tried at Monmouth Assizes and sentenced to twelve months imprisonment. Vincent was denied writing materials and only allowed to read books on religion. The Newport Rising that took place in November 1839 was partly a protest at the treatment Henry Vincent was receiving in prison.

Soon after his release from prison Vincent was rearrested and charged with using "seditious language". He conducted his own defence but he was found guilty and he received another 12 months sentence. While in prison Vincent was visited regularly by Francis Place who gave him lessons in French, history and political economy.

After his release from prison in January, 1841, Henry Vincent married Lucy Cleave, the daughter of John Cleave, the editor of the Working Man's Friend. Henry and Lucy set up home in Bath and began publication of the National Vindicator.

Henry Vincent continued to tour the country making speeches on behalf of universal suffrage. However, he had now abandoned the idea of Physical Force and gave his support to William Lovett and the Moral Force Chartists. Vincent now talked at meetings of "quietly revolutionizing our country". Like Lovett, Vincent believed that Chartists needed to concentrate on the "mental and moral improvement" of working people. At his various meetings, Vincent attempted to link the Chartist movement with the Temperance Society and helped form several teetotal political societies.

Although Henry Vincent and Fergus O'Connor had been close allies they disagreed about temperance andPhysical Force and the two men drifted apart. In in 1842 Vincent helped form the Complete Suffrage Union. Although Vincent remained a member of the National Charter Association, O'Connor saw this as a betrayal and this finally brought an end to their friendship.

The National Vindicator ceased publication in 1842 but Vincent continued to give lectures on a wide variety of different subjects. He also stood, unsuccessfully, as an independent Radical at Ipswich (1842 and 1847), Tavistock (1843), Kilmarnock (1844), Plymouth (1846) and York (1848 and 1852).

A supporter of the anti-slavery movement in America, Vincent was invited to make several lecture tours in that country (1866, 1867 and 1875-76). He always took an interest in international politics and in 1876 was very active in the campaign against the Bulgarian atrocities.

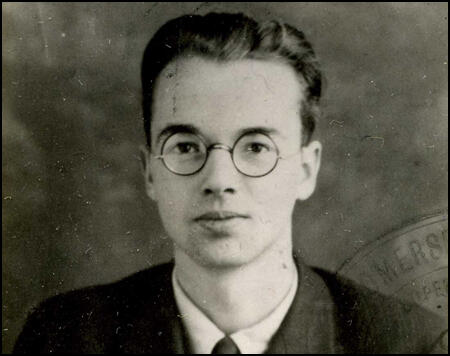

On this day in 1911 Klaus Fuchs was born in Rüsselsheim, Germany. He was the third child in the family of two sons and two daughters of Emil Fuchs and his wife, Else Wagner. According to Mary Flowers: "His father, renowned for his high Christian principles, was a pastor in the Lutheran church who joined the Quakers later in life and eventually became professor of theology at Leipzig University. Fuchs's grandmother, mother, and one sister all took their own lives, while his other sister was diagnosed as schizophrenic."

Klaus Fuchs studied physics and mathematics at the University of Leipzig and in 1931 he joined the German Communist Party (KPD). He fled the country when Adolf Hitler took power in 1933. He taught in Paris before moving to England. He settled in Bristol and studied under Nevill Francis Mott, the Melville Wills Professor in Theoretical Physics at the University of Bristol. Soon after he arrived in the city he was the subject of a police enquiry. "The German Counsul in Bristol named him as an extremist left-wing agitator. Not a great deal of credence was given to the allegation because such denunciations were fairly frequent and anyway the young physicist was just one of thousands of Germans who fled their homeland for ideological reasons."

After obtaining his PhD. He took a DSc at Edinburgh University under the guidance of Max Born, one of the pioneers of the new quantum mechanics. After the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 he was interned with other German refugees in camps on the Isle of Man. According to Andrew Boyle, The Climate of Treason (1979): "His spell behind barbed wire had merely hardened Fuchs's secret Communist faith, a process not reversed by the German attack on the Soviet Union." He was then transferred to Sherbrooke Camp in Canada where he met Hans Kahle, who had fought with the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. Kahle gave Fuchs some addresses of left wing friends, including that of Charlotte Haldane.

Klaus Fuchs was was released following representations from many distinguished scientists, protesting that his skills were going to waste. Rudolf Peierls, who worked at Birmingham University, recruited Klaus Fuchs to help him with his research into atomic weapons: "In 1940, when it was clear that an atomic weapon was a serious possibility, and that it was urgent to do experimental and theoretical work, I wanted someone to help me with the theoretical side. Most competent theoreticians were already doing something important, and when I heard that Fuchs, whom I knew and respected as a physicist from his work at Bristol, was back in the UK, temporarily in Edinburgh, it seemed a good idea to try to get him to come to Birmingham. There was at first some difficulty about security clearance, and I was told I could not tell him what it was all about... I explained that in the kind of work that had to be done he could be of no use to me and unless he knew exactly what one was trying to do, and that there was no half-way house. In the end he was cleared."

According to a document in the NKVD archives, Klaus Fuchs began spying for the Soviet Union in August 1941: "Klaus Fuchs has been our source since August 1941, when he was recruited through the recommendation of Urgen Kuchinsky (an exiled German Communist resident in Great Britain). In connection with the laboratory's transfer to America, Fuchs's departure is expected, too. I should inform you that measures to organize a liaison with Fuchs in America have been taken by us, and more detailed data will be conveyed in the course of passing Fuchs to you." Another file says that Fuchs passed material to their agent for the first time in September 1941.

Fuch's Soviet controller was Ursula Beurton: "Klaus and I never spent more than half an hour together when we met. Two minutes would have been enough but, apart from the pleasure of the meeting, it would arouse less suspicion if we took a little walk together rather than parting immediately. Nobody who did not live in such isolation can guess how precious these meetings with another German comrade were."

In 1943 Klaus Fuchs went with Peierls to join the Manhattan Project, which was the codename given to the American atomic bomb programme based in Los Alamos. However, Fuchs was based in the research unit in New York City. Over the next few months he met five times with his Soviet contact. On 21st January, 1944, the agent sent a report on Fuchs to GRU headquarters: "While working with us, Fuchs passed us a number of theoretical calculations on atomic fission and creation of the uranium bomb... His materials were appraised highly." The report also stated that Fuchs was a "devout Communist... whose only financial reward consisted of occasional gifts."

Fuchs's courier was Harry Gold. He sometimes went to the house of Fuchs' sister, who was living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to meet with Fuchs. Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999), has pointed out: "The NKVD had chosen Gold, an experienced group handler, as Fuchs' contact on the grounds that it was safer than having him meet directly with a Russian operative, but Semyon Semyonov was ultimately responsible for the Fuchs relationship."

Gold reported after his first meeting with Klaus Fuchs: "He (Fuchs) obviously worked with our people before and he is fully aware of what he is doing... He is a mathematical physicist... most likely a very brilliant man to have such a position at his age (he looks about 30). We took a long walk after dinner... He is a member of a British mission to the U.S. working under the direct control of the U.S. Army... The work involves mainly separating the isotopes... and is being done thusly: The electronic method has been developed at Berkeley, California, and is being carried out at a place known only as Camp Y... Simultaneously, the diffusion method is being tried here in the East... Should the diffusion method prove successful, it will be used as a preliminary step in the separation, with the final work being done by the electronic method. They hope to have the electronic method ready early in 1945 and the diffusion method in July 1945, but (Fuchs) says the latter estimate is optimistic. (Fuchs) says there is much being withheld from the British. Even Niels Bohr, who is now in the country incognito as Nicholas Baker, has not been told everything."

Fuchs met Gold for a second meeting on 25th February, 1944, where he turned material with his personal work on "Enormoz". At a third meeting on 11th March, he delivered fifty additional pages. Gold reported to Semyon Semyonov that "(Klaus Fuchs) asked me how his first stuff had been received, and I said quite satisfactorily but with one drawback: references to the first material, bearing on a general description of the process, were missing, and we especially needed a detailed schema of the entire plant. Clearly, he did not like this much. His main objection, evidently, was that he had already carried out this job on the other side (in England), and those who receive these materials must know how to connect them to the scheme. Besides, he thinks it would be dangerous for him if such explanations were found, since his work here is not linked to this sort of material. Nevertheless, he agreed to give us what we need as soon as possible." On 28th March, 1944, Fuchs complained to Gold that "his work here is deliberately being curbed by the Americans who continue to neglect cooperation and do not provide information." He even suggested that he might learn more by returning to England. If Fuchs went back, "he would be able to give us more complete general information but without details."

Frustrated at the lack of success in the United States in October 1944 Major Pavel Fitin sent Leonid Kvasnikov to build up a network of atomic spies. The following month Kvasnikov was pleased to hear that Fuchs had been transferred to Los Alamos. This included Fuchs, Theodore Hall, Harry Gold, Julius Rosenberg, David Greenglass and Ruth Greenglass. On 8th January, 1945, Kvasnikov sent a message to Fitin about the progress he was making. "(David Greenglass) has arrived in New York City on leave... In addition to the information passed to us through (Ruth Greenglass), he has given us a hand-written plan of the layout of Camp-2 and facts known to him about the work and the personnel. The basic task of the camp is to make the mechanism which is to serve as the detonator. Experimental work is being carried out on the construction of a tube of this kind and experiments are being tried with explosive."

Major Pavel Fitin, the head of NKVD's foreign intelligence unit, claimed that Klaus Fuchs was the most important figure in the project he had given the codename "Enormoz". In November 1944 he reported: "Despite participation by a large number of scientific organization and workers on the problem of Enormoz in the U.S., mainly known to us by agent data, their cultivation develops poorly. Therefore, the major part of data on the U.S. comes from the station in England. On the basis of information from London station, Moscow Center more than once sent to the New York station a work orientation and sent a ready agent, too (Klaus Fuchs)." Another memorandum from NKVD stated that "Fuchs is an important figure with significant prospects and experience in agent's work acquired over two years spent working with the neighbors (GRU). After determining at early meetings his status in the country and possibilities, you may move immediately to the practical work of acquiring information and materials."

The Soviet government was devastated when the atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6th and 9th August, 1945. Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999): "On August 25, Kvasnikov responded that the station had not yet received agent reports on the explosions in Japan. As for Fuchs and Greenglass, their next meetings with Gold were scheduled for mid-September. Moscow found Kvasnikov's excuses unacceptable and reminded him on August 28 of the even greater future importance of information on atomic research, now that the Americans had produced the most destructive weapon known to humankind."

Pavel Fitin wrote to Vsevolod Merkulov: "Practical use of the atomic bomb by the Americans means the completion of the first stage of enormous scientific-research work on the problem of releasing intra-atomic energy. The fact opens a new epoch in science and technology and will undoubtedly result in rapid development of the entire problem of Enormoz - using intra-atomic energy not only for military purposes but in the entire modern economy. All this gives the problem of Enormoz a leading place in our intelligence work and demands immediate measures to strengthen our technical intelligence."

In 1946 Klaus Fuchs returned to England, where he was appointed by John Cockcroft as head of the theoretical physics division at the newly created British Nuclear Research Centre at Harwell. Fuchs approached members of the Communist Party of Great Britain in order to get back in contact with the NKVD. On 19th July, 1947, Fuchs met Hanna Klopshtock in Richmond Park.

Klopshtock arranged for Fuchs to meet Alexander Feklissov, London's deputy station chief for scientific and technical intelligence. Fuchs explained to Feklissov the principle of the hydrogen bomb on which Enrico Fermi and Edward Teller were working on at the University of Chicago. Feklissov reported: "I thanked him once again for helping us and, having noted that we know about his refusal to accept material help from us in the past, said that now conditions had changed: his father was his dependent, his ill brother (who has tuberculosis) needed his help... therefore we considered it imperative to propose our help as an expression of gratitude." Fuchs was given £200. However, he returned £100 on the grounds that he could not explain the sudden appearance of £200.

In March 1948, Feklissov received orders to keep clear of Klaus Fuchs. This was because the Daily Express had reported that British counter-intelligence were investigating three unnamed scientists who were suspected of being members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Feklissov was also told that one of Fuchs' former contacts (Ursula Beurton) had been interviewed by the FBI. The point was made that Fuchs would probably not now be in a position to give them any worthwhile information as even if he was not arrested, he would probably be barred from participating in secret scientific research work on the atomic problem. However, Feklissov continued to have meetings with Fuchs.

The NKVD became especially concerned when Judith Coplon was arrested on 4th March, 1949 in New York City as she met with Valentin Gubitchev, a Soviet employee on the United Nations staff. They discovered that she had in her handbag twenty-eight FBI memoranda. Eight days later Moscow sent Feklissov a message: "In connection with the latest events in (New York City) and in order to avoid repetition of such cases in other places, it is necessary to revise urgently and most carefully the practice of holding meetings... We ask you to revise... all methods for carrying out meetings, especially with (Fuchs)."

On 12th September 1949, MI5 was sent documents that had been uncovered by the Venona Project that suggested that Fuchs was a Soviet spy. His telephones were tapped and his correspondence intercepted at both his home and office. Concealed microphones were installed in Fuchs's home in Harwell. Fuchs was tailed by B4 surveillance teams, who reported that he was difficult to follow. Although they discovered he was having an affair with the wife of his line manager, the investigation failed to produce any evidence of espionage.

In January 1950, Percy Sillitoe, the head of MI5, wrote to Fuchs's boss, Sir Archibald Rowlands pointing out: "We have had Fuchs' activities under intensive investigation for more than four months. Since it has been generally agreed that Fuchs' continued employment is a constant threat to security and since our elaborate investigation has produced no dividends, I should be grateful if you would be kind enough to arrange for Fuchs' departure from Harwell as soon as is decently possible."

Fuchs was interviewed by MI5 officers but he denied any involvement in espionage and the intelligence services did not have enough evidence to have him arrested and charged with spying. Jim Skardon later recalled: "He (Klaus Fuchs) was obviously under considerable mental stress. I suggested that he should unburden his mind and clear his conscience by telling me the full story." Fuchs replied "I will never be persuaded by you to talk." The two men then went to lunch: "During the meal he seemed to be resolving the matter and to be considerably abstracted... He suggested that we should hurry back to his house. On arrival he said that he had decided it would be in his best interests to answer my questions. I then put certain questions to him and in reply he told me that he was engaged in espionage from mid 1942 until about a year ago. He said there was a continuous passing of information relating to atomic energy at irregular but frequent meetings."

Fuchs explained to Skardon: "Since that time I have had continuous contact with the persons who were completely unknown to me, except that I knew they would hand whatever information I gave them to the Russian authorities. At that time I had complete confidence in Russian policy and I believed that the Western Allies deliberately allowed Russia and Germany to fight each other to the death. I had therefore, no hesitation in giving all the information I had, even though occasionally I tried to concentrate mainly on giving information about the results of my own work. There is nobody I know by name who is concerned with collecting information for the Russian authorities. There are people whom I know by sight whom I trusted with my life."