Barbed-Wire Entanglements

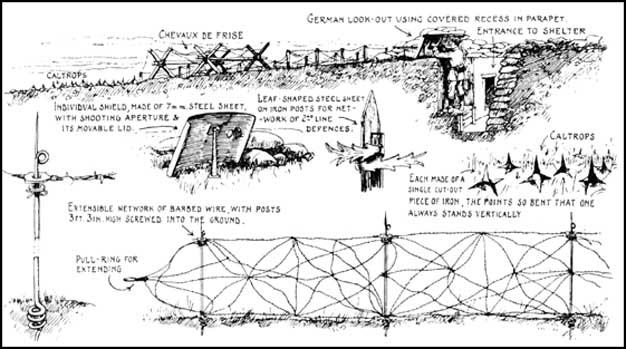

Trenches on the Western Front were usually about seven feet deep and six feet wide. These trenches were protected by thick barbed-wire entanglements. Being a member of a wiring party was one of the most unpopular duties experienced by soldiers. This involved carrying out 6 ft. steel pickets and rolls of wire. The pickets were knocked into place by muffled mallets. When fastened to the pickets, the wire was pulled out to make what was known as a apron.

Barbed-wire was usually placed far enough from the trenches to prevent the enemy from the trenches to prevent the enemy from approaching close enough to lob grenades in. Sometimes barbed-wire entanglements were set up in order to channel attacking infantry into machine-gun fire.

Barbed-wire entanglements were virtually impassable. Before a major offensive soldiers were sent out to cut a path with wire-cutters. Another tactic was to place a Bangalore Torpedo (a long pipe filled with explosive) and detonate it under the wire.

Heavy bombardment was necessary to destroy the barbed-wire. However, this always removed the crucial element of surprise. Many soldiers disputed the fact that shelling was capable of creating a gap in the wire. Arthur Coppard, who observed attempts to destroy barbed-wire entanglements at the Somme remarked: "Who told them that artillery fire would pound such wire to pieces, making it possible to get through? Any Tommy could have told them that shell fire lifts wire up and drops it down, often in a worse tangle than before."

As Ernst Toller pointed out, being caught on the wire was a terrible experience:"One night we heard a cry, the cry of one in excruciating pain; then all was quiet again. Someone in his death agony, we thought. But an hour later the cry came again. It never ceased the whole night... Later we learned that it was one of our own men hanging on the wire. Nobody could do anything for him; two men had already tried to save him, only to be shot themselves. We prayed desperately for his death. He took so long about it, and if he went on much longer we should go mad. But on the third day his cries were stopped by death."

Sometimes death came later.Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier pointed out in his book, A Brass Hat in No Man's Land (1930): "Colonel Pope, the commanding officer of the Borderers, becomes a casualty. Tripping over some rusty wire he falls and punctures his face. Two years later a military funeral leaves AIillbank Hospital, and on the gun-carriage are the mortal remains of Pope. The dirty wire killed him."

Primary Sources

(1) Ernst Toller, I Was a German (1933)

One night we heard a cry, the cry of one in excruciating pain; then all was quiet again. Someone in his death agony, we thought. But an hour later the cry came again. It never ceased the whole night. Nor the following night. Naked and inarticulate the cry persisted. We could not tell whether it came from the throat of German or Frenchman. It existed in its own right, an agonized indictment of heaven and earth. We thrust our fingers into our ears to stop its moan; but it was no good; the cry cut like a drill into our heads, dragging minutes into hours, hours into years. We withered and grew old between those cries.

Later we learned that it was one of our own men hanging on the wire. Nobody could do anything for him; two men had already tried to save him, only to be shot themselves. We prayed desperately for his death. He took so long about it, and if he went on much longer we should go mad. But on the third day his cries were stopped by death.

(2) George Coppard was a machine-gunner at the Battle of the Somme. In his book With A Machine Gun to Cambrai, he described what he saw on the 2nd July, 1916.

The next morning we gunners surveyed the dreadful scene in front of our trench. There was a pair of binoculars in the kit, and, under the brazen light of a hot mid-summer's day, everything revealed itself stark and clear. The terrain was rather like the Sussex downland, with gentle swelling hills, folds and valleys, making it difficult at first to pinpoint all the enemy trenches as they curled and twisted on the slopes.

It eventually became clear that the German line followed points of eminence, always giving a commanding view of No Man's Land. Immediately in front, and spreading left and right until hidden from view, was clear evidence that the attack had been brutally repulsed. Hundreds of dead, many of the 37th Brigade, were strung out like wreckage washed up to a high-water mark. Quite as many died on the enemy wire as on the ground, like fish caught in the net. They hung there in grotesque postures. Some looked as though they were praying; they had died on their knees and the wire had prevented their fall. From the way the dead were equally spread out, whether on the wire or lying in front of it, it was clear that there were no gaps in the wire at the time of the attack.

Concentrated machine gun fire from sufficient guns to command every inch of the wire, had done its terrible work. The Germans must have been reinforcing the wire for months. It was so dense that daylight could barely be seen through it. Through the glasses it looked a black mass. The German faith in massed wire had paid off.

How did our planners imagine that Tommies, having survived all other hazards - and there were plenty in crossing No Man's Land - would get through the German wire? Had they studied the black density of it through their powerful binoculars? Who told them that artillery fire would pound such wire to pieces, making it possible to get through? Any Tommy could have told them that shell fire lifts wire up and drops it down, often in a worse tangle than before.

(3) Captain Geoffrey Donaldson, letter (23rd June, 1916)

The night before last I took out a patrol of four men about half way across No Man's Land. There is comparatively little risk attached to this work but it is of course a considerable strain on the nerves. Last night, I went out with Wakefield and a wiring party, that is to say with about six men improving our wire entanglements. I consider on the the whole this is a nerve-racking a job as any, more so than patrol work.

(8) Charles Hudson, journal entry, quoted in Soldier, Poet, Rebel (2007)

On the evening before the attack, company commanders were called to HO for a final briefing. After the colonel had outlined the plan, the senior company commander, an ex-regular, a horsy type, tall, slim, good-looking and stupid, rose to speak. He pointed out that in accordance with previous orders he had sent out patrols to see if the bombardment had succeeded in cutting the enemy wire. The wire, he said, had not been cut and the other company commanders, including myself, confirmed this. The colonel pointed out that as we would not be asked to advance unless the enemy withdrew, too much importance need not be placed on this. This remark was the occasion for an hysterical outburst from the senior company commander. We were being asked, he said, to sacrifice ourselves against uncut wire. The order amounted to murder, he for one would absolutely refuse to let his men advance against uncut wire. The colonel repeated that our orders were dependent on the success of the main attack and the withdrawal of the enemy, but the Major had completely lost control of himself. In a wild welter of words, he inveighed against our commanders and staffs and their whole attitude towards the fighting troops. How were the staff to know whether or not the enemy opposite our sector had withdrawn? We would be ordered to advance just the same whether they had or not. At this, the colonel broke up the meeting and the Major, I am glad to say, was ordered to hand over his company.

(4) Henri Gaudier-Brezeska, letter to his father (10th November, 1914)

My lieutenant sent me out to repair some barbed wire between our trenches and the enemy's. I went through the mist with two chaps. I was lying on my back under the obstacle when pop, out came the moon, then the Boches saw me and well! Then they broke the entanglement over my head, which fell on me and trapped me. I took my butcher's knife and hacked at it a dozen times. My companions had got back to the trench and said I was dead, so the lieutenant, in order to avenge me, ordered a volley of fire, the Boches did the same and the artillery joined in, with me bang in the middle. I got back to the trench, crawling on my stomach, with my roll of barbed wire and my rifle.

(5) Guy Chapman, A Passionate Prodigality: Fragments of Autobiography (1933)

"Care to see the wire?" said my guide. I followed him gingerly over the edge of the wall, and slid clumsily down a ramp of greasy sandbags. A small party was working swiftly over a tangle of some dark stuff. Two of my own soldiers were being inducted into the ceremony of wiring. "Hold it tight, chum," growled one figure. He proceeded to smite a heavy bulk of timber with a gigantic maul, the head of which had been cunningly muffled in sandbags.

(6) Private Jack Sweeney, letter to girlfriend (May, 1916)

It is simply murder at this part of the line. There is one of our officers hanging on the German barbed wire and a lot of attempts have been made to get him and a lot of brave men have lost their lives in the attempt. The Germans know that we are sure to try and get him in so all they have to do is to put two or three fixed rifles on to him and fire every few seconds - he must be riddled with bullets by now: he was leading a bombing party one night and got fixed in the wire - the raid was a failure.

(7) Frank Percy Crozier, A Brass Hat in No Man's Land (1930)

Colonel Pope, the commanding officer of the Borderers, becomes a casualty. Tripping over some rusty wire he falls and punctures his face. Two years later a military funeral leaves AIillbank Hospital, and on the gun-carriage are the mortal remains of Pope. The dirty wire killed him.

(8) Charles Hudson, letter to his sister (undated, 1915)

We are now 150yd from Fritz and the moon is bright, so we bend and walk quietly onto the road running diagonally across the front into the Bosche line. There is a stream the far side of this - boards have been put across it at intervals but must have fallen in - about 20yd down we can cross. We stop and listen - swish - and down we plop (for a flare lights everything up) it goes out with a hiss and over the board we trundle on hands and knees. Still.

Apparently no one has seen so we proceed to crawl through a line of "French" wire. Now for 100yd dead flat weed-land with here and there a shell hole or old webbing equipment lying in little heaps! These we avoid. This means a slow, slow crawl head down, propelling ourselves by toes and forearm, body and legs flat on the ground, like it snake.

A working party of Huns are in their lair. We can just see dark shadows and hear the Sergeant, who is sitting down. He's got a bad cold! We must wait a bit, the moon's getting low but it's too bright now 5 a.m. They will stop soon and if we go on we may meet a covering party lying low. 5.10. 5.15. 5.25. 5.30. And the moon's gone.

"Cot the bombs, Sergeant?"

"'No. Sir, I forgot them!"

"Huns" and the last crawl starts.

The Bosch is moving and we crawl quickly on to the wire - past two huge shell holes to the first row. A potent row of standards are the first with a nut at the top and strand upon strand of barbed wire. The nut holds the two iron pieces at the top and the ends are driven into the ground 3ft apart. Evidently this line is made behind the parapet and brought out, the legs of the standard falling together. All the joins where the strands cross are neatly done with a separate piece of plain wire. Out comes the wire cutter. I hold the strands to prevent them jumping apart when cut and Stafford cuts. Twenty-five strands are cut and the standard pulled out. Two or three tins are cut off as we go. (These tins are hung on to give warning and one must beware of them.) Next a space 4ft then low wire entanglements as we cut on through to a line of iron spikes and thick, heavy barbed wire.

The standard has three furls to hold the wire up and strive as we can, it won't come out. "By love, it's a corkscrew, twist it round" and then, wonder of wonders, up it goes and out it comes! It is getting light, a long streak has already appeared and so we just make a line of "knife rests" (wire on wooden X-X) against the German parapet and proceed to return. I take the corkscrew and Stafford the iron double standard. My corkscrew keeps on catching and Stafford has to extract me twice from the wire, his standard is smooth and only 3ft so he travels lighter. He leads back down a bit of ditch. Suddenly a sentry fires 2 shots which spit on the ground a few yards in front. We lie absolutely flat, scarcely daring to breathe - has he seen? Then we go on with our trophies, the ditch gets a little deeper, giving cover! My heart is beating nineteen to the dozen - will it mean a machine gun, Stafford is gaining and leads by 10yd. "My God," I think, "it is a listening post ahead and this the ditch to it. I must stop him." I whisper, "Stafford, Stafford" and feel I am shouting. He stops, thinking I have got it. "Do you think it's a listening post?" There! By the mound - listen."

"Perhaps we had better cut across to the left Sir."

"Are you all right Sir," from Stafford.

I laugh, "Forgot that damned wire." (Our own wire outside our listening post). The LP occupants have gone in. Soon we are behind the friendly parapet and it is day. We are ourselves again, but there's a subtle cord between us, stronger than barbed wire, that will take a lot of cutting. Twenty to seven, 2 hrs 10 minutes of life - war at its best. But shelling, no, that's death at its worst. And I can't go again, it's a vice. Immediately after I swear I'll never do it again, the next night I find myself aching after "No Man's Land".