On this day on 25th January

On this day in 1770 radical MP Francis Burdett, the son of the Baronet of Foremark (1743–1794), was born on 25th January 1770, near Repton, Derbyshire. He was educated at Westminster School from 1786 until his expulsion in 1788, and Christ Church, from 1786 to 1788. He later toured the continent for two years, before returning to Britain in 1791.

Burdett returned to England in 1793 and soon afterwards married Sophia Coutts, the daughter of the extremely wealthy banker, Thomas Coutts. On marriage, Sophia received a dowry of £25,000. According to his biographer, Marc Baer: "There were difficult relations with his wife and her parents, caused by the Burdett family's social prejudice, Burdett's own melancholia, pedantry, and quick temper, and Sophia's possessive attachment to him. In 1795–6 Burdett came close to separating from his wife, and discussed suicide. William Stevens, his family's chaplain, commented (18 August 1795) that 'He is too much a Philosopher to be happy or to make happy’. The marriage survived to produce six children. From an affair with Lady Oxford (Jane Elizabeth Harley), Burdett probably fathered one if not two children."

Burdett succeeded his grandfather Sir Robert Burdett (1716–1797) as fifth baronet on 13 February 1797, inheriting estates at Foremark and Bramcote. Later that year Coutts purchased the rotten borough of Boroughbridge in Yorkshire from the Duke of Newcastle for £4,000. Coutts gave the seat to his son-in-law and later that year Burdett became a member of the House of Commons.

Burdett became friends with the radical lawyer, Horne Tooke. He was deeply influenced by his political views and in parliament he refused to join the Whigs or the Tories. This enabled him to act as an independent. His maiden speech was on Ireland and he upset most of his colleagues with the claim that the government was guilty of the "oppression of an enslaved and impoverished people".

Burdett opposed the suspension of Habeas Corpus in 1796 and criticised all attempts by the government to suppress individual freedom. Burdett later recalled: "The best part of my character is a strong feeling of indignation at injustice & oppression and a lively sympathy with the sufferings of my fellows". Marc Baer has argued: "He based his anti-establishment politics on the need to protect individuals put upon by those in power."

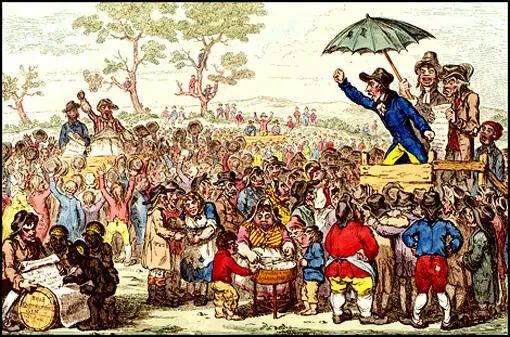

Edna Healey has argued: "He was at the height of his political fame in the first decade of the nineteenth century. It was his campaigns in 1798 and 1800 on behalf of mutinous sailors imprisoned in Cold Bath Fields Prison and his fierce attack on the conditions there that won him popular support. During his election campaigns his appearance on the hustings, elegant and long-limbed, brought cheering crowds.... A passion for freedom, justice and humanity inspired his political career."

Burdett was one of the few members of the House of Commons that supported the idea of parliamentary reform. Radicals in London approached Burdett and asked him to stand as their candidate for the county of Middlesex. He was elected in 1802, but was defeated in the elections held in 1804 and 1806. It has been estimated that Burdett spent £100,000 during these two elections.

Burdett now switched to Westminster, the constituency with a reputation for electing Radicals. At this time, Westminster had one of the largest electoral rolls in England. Most of the 13,863 voters were shopkeepers and artisans who had a strong dislike of aristocratic privilege. Sir Francis Burdett easily won the 1807 election, polling more votes than the combined total of the three defeated candidates. He later recalled: "The best part of my character is a strong feeling of indignation at injustice & oppression & a lively sympathy with the sufferings of my fellows".

Burdett became close friends with William Cobbett. In 1809 he was charged with a breach of privilege by the House of Commons. This resulted from an article that appeared in Cobbett's Political Register. Burdett was defended by Samuel Romilly. Burdett's biographer, Marc Baer, has commented: "The confrontation between the ‘Man of the People' and the Perceval government had been building for some time, owing to Burdett's speeches about the unrepresentative character of the Commons, criticism of the war and the sale of army commissions, and tiresome lectures on the ancient constitution. On 6 April the Commons voted to commit Burdett to the Tower of London, whereupon he challenged the speaker's warrant and barricaded himself in his London house."

Burdett was arrested on the morning of 9th April 1810 and was ordered to was confined to the Tower of London until the end of the parliamentary session on 21st June. The government was too afraid to expel him from Parliament. When Burdett was released he cancelled a march through London, fearing further riots and loss of life. His biographer has argued: "Burdett's popularity reached its peak after the incarceration; three separate biographies of him were published during that spring. But he proceeded to disappoint his followers by preventing a procession through London on his release, fearing further riots and loss of life, or that he would be assassinated." Richard Carlile complained that "the mind of the people has marched, and Sir Francis has not been disposed to march with it".

On 21st April, 1814, his daughter, Angela Burdett, the youngest of his six children was born at 80 Piccadilly, London, on 21st April, 1814. Burdett had been having an affair with Jane Harvey, the Countess of Oxford and as Edna Healey, the author of Lady Unknown: The Life of Angela Burdett-Coutts (1978) has pointed out: "She was the child of the reconciliation between Sir Francis and Sophia. But Sophia still had to endure the strain of conflict between husband and father. Thomas Coutts's attitude to his son-in-law can be imagined. During the years before and after Angela's birth even his tolerance was strained. But there was no moralizing on the subject of infidelity. For in the years when Sir Francis was finding release in the arms of Lady Oxford... he was having a relationship with an enchanting young actress called Harriot Mellon."

Sir Francis Burdett was now seen as the leader of the Radicals in the House of Commons. Burdett introduced motions for parliamentary reform and supported all attempts to expose government corruption. Burdett also supported the campaign against the slave trade. In 1816 he attacked William Wilberforce when he refused to complain about the suspension of Habeas Corpus. Burdett commented: "How happened it that the honourable and religious member was not shocked at Englishmen being taken up under this act and treated like African slaves?" Wilberforce replied that Burdett was opposing the government in a deliberate scheme to destroy the liberty and happiness of the people."

In 1819 Burdett led the campaign for an independent inquiry into the Peterloo Massacre. Burdett wrote to the Westminster electors on 22nd August 1820 condemning the massacre and calling on "the gentlemen of England" to join the masses in protest meetings. Burdett was prosecuted for seditious libel, found guilty, sentenced to the Marshalsea Prison for three months, and fined £2,000. Samuel Bamford, a weaver from Manchester, wrote during this period that Burdett "was our idol".

In a speech on the Peterloo Massacre in the House of Commons on 15th May 1821, Burdett argued: "The pretence of the people having carried arms to the meeting was utterly groundless; and to talk of their having commenced the attack upon the armed soldiers, was, on the face of it, absurd and ridiculous. The people knew they had no means of repelling the attack. They thought they had assembled under the protection of the law, and they knew they had no other protection than that law. The wretches who had perpetrated the massacre at Manchester were at the time in a state of intoxication. When they attacked, sword in hand, the people fled, or attempting to fly, from the dreadful charge made upon them; but, to their horror and surprise, they found flight impracticable; for the avenues of the place were closed by armed men. On one side they were driven back at the point of the bayonet by the infantry; while on the other they were cut down by the yeomanry."

Burdett was also a strong advocate of religious toleration and several times attempted to persuade Parliament to grant Catholics equal rights with Protestants. The Catholic Emancipation Act was finally passed in 1829. Burdett also had the satisfaction of seeing the start of parliamentary reform with the passing of the 1832 Reform Act.

Burdett became friends with Benjamin Disraeli and supported him as the Radical candidate for High Wycombe. Disraeli later wrote about Burdett: "He was tall, and had kept his distinguished figure; a handsome man, with a musical voice, and a countenance now benignant, though very bright... He still retained the same fashion of costume in which he had written up to Westminster more than half a century ago... to support his dear friend Charles Fox; real top-boots, and a blue coat and buff waistcoat."

As he got older, Burdett became more conservative. In his sixties he began to argue that the Catholic Emancipation Act and the 1832 Reform Act had gone too far. These opinions upset the Radicals and his thirty years as M.P. for Westminster came to an end in 1837. He was approached by the Tories to be their candidate in North Wiltshire. Sir Francis Burdett accepted their offer and he won the election.

Harriot Mellon Coutts, Duchess of St Albans, died on 6th August, 1837. The will was read in the presence of the various relatives. To the surprise of all concerned, it was announced that almost the entire estate was left to Burdett's daughter, Angela Burdett-Coutts. This amounted to some £1.8 million (£165 million in 2012 figures). The duchess's will made the inheritance conditional on Angela not marrying a foreign national, in which event it would pass to the next in line, and stipulated that her successors take the surname of Coutts. It has been claimed that after Queen Victoria she was the wealthiest woman in England. The Morning Herald estimated that "the weight in gold is 13 tons, 7 cwt, 3 qtrs, 13 lbs and would require 107 men to carry it, supposing that each of them carried 289 lbs - the equivalent of a sack of flour". Angela gave her mother, Lady Sophia Burdett, £8,000 a year and all her sisters received an allowance of £2,000 a year.

Under the guidance of her father, she decided to give a large percentage of the money to good causes. Edna Healey, the author of Lady Unknown: The Life of Angela Burdett-Coutts (1978) has argued: "She absorbed his values, which, in spite of his change of party (he was now a Tory MP) remained humanitarian and progressive." Her father also encouraged her to be interested in science and she provided funds for research in physics, geology, archaeology and the natural sciences. At his home she met men like Charles Babbage, Michael Faraday and Charles Wheatstone. In 1839 she provided financial backing for Babbage's "calculating engine", the forerunner of the modern computer.

Francis Burdett remained the Tory M.P. for North Wiltshire until his death on 23rd January 1844 at his residence at 25 St James's Place, two days short of his seventy-fourth birthday, from a pulmonary embolism. He was buried in the family vault in Ramsbury Church together with his wife, who had died eleven days earlier. power."

On this day in 1792 London Corresponding Society has its first public meeting. In January 1792 a group of four men, including Thomas Hardy, a London shoemaker, began meeting to discuss the possibility of forming a group of working men in order to campaign for the vote. On the 25th January 1792 they held a public meeting on parliamentary reform. Only eight people attended but the men decided to form a group called the London Corresponding Society. Early members included John Thelwall, John Horne Tooke, Joseph Gerrald, Olaudah Equiano and Maurice Margarot.

As well as campaigning for the vote, the strategy was to create links with other reforming groups in Britain. Thomas Hardy was appointed as treasurer and secretary of the organisation. The society passed a series of resolutions and after being printed on handbills, they were distributed to the public. These resolutions also included statements attacking the government's foreign policy. A petition was started and by May 1793, 6,000 members of the public had signed saying they supported the resolutions of the London Corresponding Society.

By the summer of 1793 the London Corresponding Society had made contact with parliamentary reform groups in Manchester, Sheffield, Nottingham, Derby, Stockport and Tewksbury. They also had meetings with the Society for Constitutional Information, an organisation formed by Major John Cartwright. At the end of 1793 Thomas Muir and the supporters of parliamentary reform in Scotland began to organise a convention in Edinburgh. The Society sent two delegates Joseph Gerrald and Maurice Maragot, but the men and other leaders of the convention were arrested and tried for sedition. Several of the men, including Gerrald and Maragot, were sentenced to fourteen years transportation.

The reformers were determined not to be beaten and Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall began to organise another convention. When the authorities heard what was happening, Hardy and the other two men were arrested and committed to the Tower of London and charged with high treason. The men's trial began at the Old Bailey on 28th October, 1794. The prosecution, led by Lord Eldon, argued that the leaders of the London Corresponding Society were guilty of treason as they organised meetings where people were encouraged to disobey King and Parliament. However, the prosecution was unable to provide any evidence that Hardy and his co-defendants had attempted to do this and the jury returned a verdict of "Not Guilty".

The government continued to persecute supporters of parliamentary reform. Habeas Corpus was suspended in 1794, enabling the government to detain prisoners without trial. In 1797 Samuel Romilly successfully defended John Binns, against a charge of seditious words.

The Seditious Meetings Act made the organisation of parliamentary reform gatherings extremely difficult. Finally, in 1799, the government persuaded Parliament to pass a Corresponding Societies Act. It was now illegal for the London Corresponding Society to meet and the organisation came to an end.

On this day in 1819 Ernest Jones, the son of Major Charles Jones, the equerry to William, Duke of Cumberland, was born in Berlin on 25th January, 1819. Major Jones and his family lived at Reinbeck, Holstein, until it was decided to move back to England in 1838.

Ernest Jones began training as a lawyer in 1838 and six years later he qualified as a Barrister. While a student, Jones married Jane Atherley, the daughter of a large landowner in Cumberland, in June 1841. Jones inherited his father's property on his death in 1844, but some unwise business decisions resulted in bankruptcy.

In 1846 Jones joined the Chartist Movement and soon became a follower of Feargus O'Connor, the leader of the Physical Force movement. A good orator, organizer and writer, Jones was highly valued by O'Connor who employed him as a journalist on the Northern Star. O'Connor and Jones became co-editors of The Labourer, a new monthly journal of literature and politics.

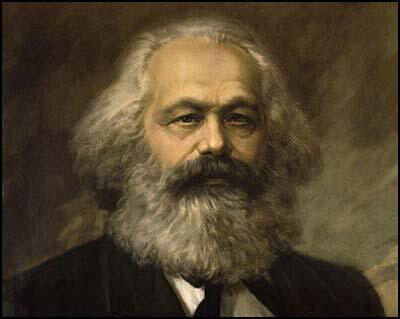

Jones also wrote poetry and his book Chartist Songs, were published in August 1846. In 1847 worked closely with George Julian Harney and the two men met and were influenced by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Harney and Jones now considered themselves as socialists, and suggested that Chartism should become a "workers' party". In July 1847, Jones stood as the Radical candidate in Halifax, but obtained only 208 votes.

On 6th June 1848, Jones was arrested for making a seditious speech where he predicted that the "green flag of Chartism will soon be flying over Downing Street". Jones was found guilty and sentenced to two years in Tothill Fields Prison, Westminster. Conditions in the prison were appalling and two of his fellow Chartist prisoners died of cholera. As Jones refused to pick oakum in prison he was placed in solitary confinement. Kept in a dark and damp 13 ft. by 6 ft. cell, Jones' health was badly damaged during this period. As a further punishment, Jones was fed on bread and water and was refused permission to have a pen, ink or paper. With the help of friends, Jones was able to keep writing and while in prison he produced his epic poem, The Revolt of Hindostan.

R. G. Gammage argued: "Ernest Jones poetry received the most unqualified praise of the most aristocratic journals; he was hailed by all of them as a great poet - one of the greatest of modern times. In 1846 Jones became a politician as well as a poet. Unknown previously to the working class, he came into their ranks under the patronage of Feargus O'Connor. Jones was small in stature; but his voice was stentorian, his delivery good, his language brilliant, his action heroic - and, above all, he had a concealed cunning. In the art of flattery, no demagogue ever excelled him."

After his release from prison in July 1850, Jones wrote for the Red Republican. The following year George Julian Harney and Jones started a new radical newspaper, The Friend of the People. After a dispute with Harney in 1851, Jones started his own journal, The People's Paper. Jones attempted to publish what he hoped would be a "complete newspaper". As well as news of the Chartist movement, The People's Paper included reports of parliamentary debates, public meeting and what Jones called "legal, political, mercantile and general intelligence." The newspaper became a socialist newspaper and one of his main contributors included Karl Marx, who was now living in exile in London.

Although Chartism was in decline, Jones realised that it was virtually important that at least one newspaper remained that promoted universal suffrage. Jones was not able to sell enough copies to finance The People's Paper and therefore had to persuade sympathizers to donate money to pay for it to be printed. Penny collections were organised in the areas where Chartism was still strong. By May 1854, the size of the newspaper had been increased to 12 pages. It also had a pictorial supplement with engravings of events like the Crimean War. Circulation reached 3,000 but the newspaper continued to lose money and in September, 1858, The People's Paper ceased publication.

Ralph Miliband has pointed out: "A remarkable illustration of the truth that men are prisoners of their times. The circumstances of the fifties doomed him to failure as a leader of labour. He (Ernest Jones) preached social revolution to a working class that had turned away from it; he was a militant political organiser when both militancy and political organisation had been replaced by trade unionism geared to limited aims, primarily economic, as the typical form of working class actions."

Ernest Jones continued to be involved in politics and in April 1857 he stood as the Radical candidate for the Nottingham seat in the House of Commons. He received 604 votes but failed to get elected. He also published other radical papers such as The London News and The Cabinet, but the both failed to make a profit. In 1860 Jones returned to his career as a barrister, where he concentrated his efforts defending radicals, including a group of Irish Fenians charged with murder.

As well as journalism, Jones also wrote novels, his most important being: The Battleday (1855), The Painter of Florence (1856), The Emperor's Vigil (1856), The Beldagon Church (1860) and Corayda (1860).

Ernest Jones died on 26th January, 1869. An estimated 100,000 people lined the streets of Manchester during his funeral.

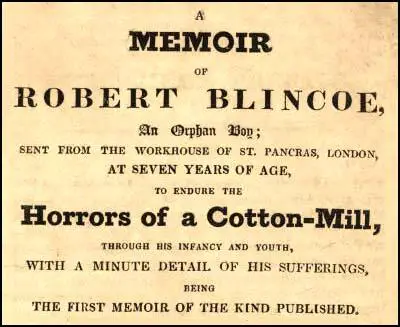

On this day in 1828 Richard Carlile starts publishing Robert Blincoe's account of child labour. Blincoe was born in 1792. At four years old Blincoe was placed in St. Pancras Workhouse, London. He was later told that his family name was Blincoe but he never discovered what happened to his parents. At the age of six Robert was sent to work as a chimney boy. As Nicholas Blincoe, his great-great-great-grandson, has pointed out: "As coal replaced wood-burning grates, chimneys became narrower to create a more intense draught. This was why small boys were needed, but the work was dangerous - the children risked injury, suffocation, lung disease and scrotal cancer as they climbed the chimney stacks. Robert was warned by older inmates not to put himself forward." However, Robert was not a success and after a few months he was returned to the workhouse.

In 1799, Lamberts recruited Robert and eighty other boys and girls from St. Pancras Workhouse. The boys were to be instructed in the trade of stocking weaving and the girls in lacemaking at Lowdam Mill, situated ten miles from Nottingham. Blincoe completed his apprenticeship in 1813, worked as an adult operative until 1817, when he set up his own small cotton-spinning business. Blincoe married a woman called Martha in 1819.

John Brown, a journalist from Bolton, met Robert Blincoe in 1822. He later explained: "It was in the spring of 1822, after having devoted a considerable time to the investigating of the effect of the manufacturing system, and factory establishments, on the health and morals of the manufacturing populace, that I first heard of the extraordinary sufferings of Robert Blincoe. At the same time, I was told of his earnest wish that those sufferings should, for the protection of the rising generation of parish children, be laid before the world. If this young man had not consigned to a cotton-factory, he would probably have been strong, healthy, and well grown; instead of which, he is diminutive as to statue, and his knees are grievously distorted."

Brown interviewed Blincoe for an article he was writing on child labour. Brown found the story so fascinating he decided to write Blincoe's biography. John Brown gave the biography to his friend Richard Carlile who was active in the campaign for factory legislation. Later that year John Brown committed suicide.

Robert Carlile eventually decided to publish Robert Blincoe's Memoir in his radical newspaper, The Lion. The story appeared in five weekly episodes from 25th January to 22nd February 1828. The story also appeared in Carlile's The Poor Man's Advocate. Five years later, John Doherty published Robert Blincoe's Memoir in pamphlet form.

As a result of a fire in 1828, Robert Blincoe's spinning machinery was destroyed. Unable to pay his debts, Blincoe was imprisoned in Lancaster Castle. After his release he became a cotton-waste dealer and his wife ran a grocer's shop.

Blincoe's business was successful and he was able to pay for his three children to be educated. One of his sons went on to graduate from Queens College, University of Cambridge to become a Church of England clergyman.

In January 1837, Richard Bentley, the owner of the journal, Bentley's Miscellany, agreed to publish Oliver Twist, a serial written by Charles Dickens. It has been argued by John Waller, the author of Oliver: The Real Oliver Twist (2005) argues that he took his story from the memoirs of Blincoe.

Robert Blincoe carried on the business of a cotton-waste dealer in Turner Street. Abel Heywood got to know him in Manchester during this period: "He was a little man in height, his legs being very crooked, the result of his early life in a cotton factory." Robert Blincoe died of bronchitis at the home of his daughter in Gunco Lane, Macclesfield in 1860.

On this day in 1830, about 10,000 people attended the first meeting of the Birmingham Political Union. People listened for six hours to speeches made by Thomas Attwood and other leaders of the organisation. Another meeting in May at the Beardsworth Repository in Birmingham was attended by over 80,000 people. Other manufacturing towns in Britain began to follow Birmingham's example and formed Political Unions.

For the next two years Attwood was one of the main leaders in the campaign for parliamentary reform. When the Reform Act was eventually passed in 1832, Attwood was installed as a freeman of the City of London in recognition of the important role he had played in the fight for the vote. In the general election held in the autumn of 1832 Attwood and another leading member of the Political Union, Joshua Scholefield, were elected unopposed as Birmingham's first two MPs.

Attwood worked hard to convince the House of Commons of the wisdom of his economic ideas. However, he was unsuccessful at persuading his fellow MPs and he eventually came to the conclusion that a further reform of Parliament was needed. In May, 1837, the Birmingham Political Union was revived. In June a new list of demands were drawn up, including: currency reform, household suffrage, triennial parliaments, payment of MPs, and the abolition of the property qualification.

In January 1838 Thomas Attwood and the Birmingham Political Union began to work with the London Working Men's Association in the fight for the vote. However, Attwood objected to the aggressive speeches made by Feargus O'Connor and was much more closely aligned with William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, John Cleave and the other Moral Force Chartists.

In June 1839, Attwood presented the first National Petition to the House of Commons. Although it had been signed by over 1,280,000 people, the Commons rejected the petition by 235 votes to 46. Frustrated by the unwillingness of Parliament to respond to public pressure, and aware that many of the Chartist leaders had doubts about currency reform, Attwood decided to resign from Parliament. Attwood took no further part in politics. In later life Attwood suffered from creeping paralysis.

On this day in 1845, Karl Marx received an order deporting him from France. Marx and Friedrich Engels decided to move to Belgium, a country that permitted greater freedom of expression than any other European state. They settled in Brussels, where there was a sizable community of political exiles, including the man who converted him to socialism, Moses Hess.

Engels helped to financially support Marx and his family. Engels gave Marx the royalties of his recently published book, Condition of the Working Class in England and arranged for other sympathizers to make donations. This enabled Marx the time to study and develop his economic and political theories. Marx spent his time trying to understand the workings of capitalist society, the factors governing the process of history and how the proletariat could help bring about a socialist revolution.

In July 1845 Marx and Engels visited England. They spent most of the time consulting books in Manchester Library. Marx also visited London where he met the Chartist leaders, George Julian Harney and other political exiles from Europe. He praised Feargus O'Connor and wrote articles for the Northern Star and claimed it was "the only English paper worth reading for the continental democrats".

Marx returned to Brussels and along with Engels finished their book, The German Ideology. It begins with one of Marx's attention-grabbing generalisations: "Hitherto men have always formed wrong ideas about themselves, about what they are and what they ought to be." He then went on to attack other German philosophers that he had previously praised. This included Ludwig Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer and Max Stirner.

On this day in 1874 William Somerset Maugham was born in the British Embassy in Paris on 25th January, 1874. William's father, Robert Ormond Maugham, a wealthy solicitor, worked for the Embassy in France. Maugham's mother died of tuberculosis when he was seven and his father of cancer three years later.

Maugham later wrote in Summing Up (1938): "My parents died when I was so young, my mother when I was eight, my father when I was ten, that I know little of them but from hearsay...He was forty when he married my mother, who was more than twenty years younger. She was a very beautiful woman and he was a very ugly man. I have been told that they were known in the Paris of that day as Beauty and the Beast.... I have a little photograph of her, a middle-aged woman in a crinoline with fine eyes and a look of good-humoured determination. My mother was very small, with large brown eyes and hair of a rich reddish gold, exquisite features, and a lovely skin." Lady Anglesey told Maugham that she had once said to his mother: "You're so beautiful and there are so many people in love with you, why are you faithful to that ugly little man you've married?" His mother answered: "He never hurts my feelings."

After the death of his parents he was sent to live with his uncle, the Rev. Henry Maugham, in Whitstable, Kent. His biographer, Bryan Connon, has pointed out: "French was Maugham's first language and when he attended King's School, Canterbury, he was taunted for his inadequate English and as a result developed a defensive speech hesitancy which never entirely left him and intensified in times of stress. He moved to Heidelberg when he was sixteen to learn German and came under the influence of John Ellingham Brooks, who seduced him. Ten years his senior and an ostentatious homosexual, Brooks encouraged his ambitions to be a writer and introduced him to the works of Schopenhauer and Spinoza. Maugham returned to England when he was eighteen and, instead of becoming an accountant or a parson as his uncle proposed, enrolled as a student at St Thomas's Hospital, London, where he believed he would have personal freedom and the time to write."

While training to be a doctor Maugham worked as an obstetric clerk in the slums of Lambeth. He used these experiences to help him write his first novel, Liza of Lambeth (1897). The book created a great deal of controversy as it dealt with Liza, a fun-loving factory worker, and her affair with Jim, a married man. The Daily Mail complained about one scene that involved a street fight between the pregnant Liza and Jim's wife which leads to Liza's miscarriage and death. One reviewer claimed Maugham had "imitated" a story by Arthur Morrison called by Liza Hunt of Bow that appeared in Tales of Mean Streets (1894). The critic claimed "the mimicry, indeed, is deliberate and unashamed". The book sold well and he decided to abandon medicine and become a full-time writer.

Maugham achieved fame with his play Lady Frederick (1907), a comedy about money and marriage. By 1908 Maugham had four plays running simultaneously in London. A cartoon by Bernard Partridge in Punch (24th June 1908) showed a worried Shakespeare in front of the playbills. Bryan Connon, the author of Somerset Maugham and the Maugham Dynasty (1997), pointed out: "Maugham's success was repeated in New York, and he celebrated his good fortune by moving into a lavishly appointed house in Mayfair, London, with Walter Payne. As well-to-do bachelors, both men were socially popular. Contemporary photographs show Maugham, a small man, to be good looking, sexy, and fashion-conscious. His dandyism was captured by Sir Gerald Kelly in a full-length portrait of 1911".

In 1914 Maugham met the 22 year old American, Gerald Haxton, in London. The two men became lovers. On the outbreak of the First World War, Maugham, now aged forty, and Haxton, joined a Red Cross ambulance unit in France. In 1915 they parted when Haxton joined the American Army. Maugham went to live in New York City and in 1915 he published his most famous novel, Of Human Bondage.

Maugham had sexual relationships with both men and women and in 1915, Syrie Wellcome, the daughter of Dr. Thomas Barnardo, gave birth to his child. Her husband, Henry Wellcome, cited Maugham as co-respondent in divorce proceedings. After the divorce in 1916, Maugham married Syrie. The marriage was unhappy and after they divorced he denied that Liza was his natural daughter.

In 1916 Maugham was invited by Sir John Wallinger, head of Britain's Military Intelligence (MI6) to act as a secret service agent. Maugham agreed and acted as a link between MI6 in London and its agents working in Europe. The following year he became involved in events in Russia.

When the Tsar Nicholas II abdicated on 13th March, a Provisional Government, headed by Prince George Lvov, was formed. On 5th May, Pavel Milyukov and Alexander Guchkov, the two most conservative members of the Provisional Government, were forced to resign. Guchkov was now replaced as Minister of War by Alexander Kerensky. He toured the Eastern Front where he made a series of emotional speeches where he appealed to the troops to continue fighting. Kerensky argued that: "There is no Russian front. There is only one united Allied front." Kerensky now appointed General Alexei Brusilov as the Commander in Chief of the Russian Army. On 18th June, Kerensky announced a new war offensive.

The Provisional Government made no real attempt to seek an armistice with the Central Powers. Lvov's unwillingness to withdraw Russia from the First World War made him unpopular with the people and on 8th July, 1917, he resigned and was replaced by Kerensky. Ariadna Tyrkova, a member of the Constitutional Democrat Party, commented: "Kerensky was perhaps the only member of the Government who knew how to deal with the masses, since he instinctively understood the psychology of the mob. Therein lay his power and the main source of his popularity in the streets, in the Soviet, and in the Government."

The British ambassador, George Buchanan welcomed the appointment and reported back to London: "From the very first Kerensky had been the central figure of the revolutionary drama and had, alone among his colleagues, acquired a sensible hold on the masses. An ardent patriot, he desired to see Russia carry on the war till a democratic peace had been won; while he wanted to combat the forces of disorder so that his country should not fall a prey to anarchy. In the early stages of the revolution he displayed an energy and courage which marked him out as the one man capable of securing the attainment of these ends."

Mansfield Smith-Cumming, the head of MI6, decided that the British government should do everything possible to keep Kerensky in power. He contacted William Wiseman, their man in New York City and supplied Wiseman with $75,000 (approximately $1.2 million in modern prices) for Kerensky's Provisional Government. A similar sum was received from the Americans. Wiseman now approached Somerset Maugham (to whom he was related by marriage) in June 1917, to go to Russia. Maugham was "staggered" by the proposition: "The long and short of it was that I should go to Russia and keep the Russians in the war."

Maugham, who could speak Russian, was asked by Wiseman to "guide the storm". Maugham told Wiseman: "I was staggered by the proposition. I told Wiseman that I did not think I was competent to do that sort of thing that was expected of me." He asked for forty-eight hours to think it over. He was in the early stages of tuberculosis, had a high fever and was coughing up blood. Maugham later wrote: "An X-ray photograph showed clearly that I had tuberculosis of the lungs. But I could not miss the opportunity of spending certainly a considerable time in the country of Tolstoi, Dostoyevski, and Chekov; I had a notion that in the intervals of the work I was being sent to do I could get something for myself that would be of value; so I set my foot hard on the loud pedal of patriotism and persuaded the physician I consulted that under the tragic circumstances of the moment I was taking no undue risk."

Maugham was supplied with $21,000 (worth approximately $350,000 today) for expenses and travelling from the west coast of the United States, through Japan and Vladivostok, Maugham reached Petrograd in early September 1917. With him went a group of four Czechoslovak refugees headed by Emanuel Voska, Director of the Slav Press Bureau in New York City. Maugham described Voska as the perfect spy: "Ruthless, wise, prudent and absolutely indifferent to the means by which he reached his ends... There was something terrifying about him... he was capable of killing a fellow creature without a trace of ill-feeling." Voska made contact with Tomáš Masaryk in the hope of mobilizing Czech and Slovak elements in Russia to work for the Allied cause. Maugham was impressed by his "good sense and determination" and helped set up a press bureau to disseminate anti-German propaganda.

While in Petrograd Maugham met a former mistress, Sasha Kropotkin, the daughter of Peter Kropotkin, who had a good relationship with Alexander Kerensky and the Provisional Government. Maugham entertained Kerensky or his ministers once a week at the Medvied, the best restaurant in Petrograd, paying for the finest vodka and caviar from the funds supplied by Wiseman. Maugham later recalled "I think Kerensky must have supposed that I was more important than I really was for he came to Sasha's apartment on several occasions and, walking up and down the room, harangued me as though I were at a public meeting for two hours at a time".

Maugham also met Boris Savinkov, a member of the government and a former terrorist. Maugham described Savinkov as "the most remarkable man I met." He found it difficult to believe that Savinkov had been personally responsible for the assassination of a number of senior imperial officials in the years before the war. Maugham wrote, he had the prosperous look of a lawyer." Savinkov believed that if the Bolsheviks gained power they would "annihilate" opposition leaders. Savinkov therefore wanted the government to arrest Lenin and other leading Bolsheviks: "Either Lenin will stand me up in front of a wall and shoot me or I shall stand him in front of a wall and shoot him."

Somerset Maugham worked closely with Major Stephen Alley, the MI1(c) station chief in Petrograd. On 16th October Maugham telegraphed Wiseman recommending a programme of propaganda and covert action. He said that Voska and Masaryk could both conduct "legitimate propaganda" and act as a cover for "other activities" in support of the Mensheviks and against the Bolsheviks. He also proposed setting up a "special secret organisations" recruited from Poles, Czechs and Cossacks with the main aim of "unmasking... German plots and propaganda in Russia".

On 31st October 1917 Maugham was summoned by Kerensky and asked to take an urgent secret message to David Lloyd George appealing for guns and amununition. Without that help, said Kerensky, "I don't see how we can go on. Of course, I don't say that to the people. I always say that to the people. I always say that we shall continue whatever happens, but unless I have something to tell my army it's impossible". Maugham was unimpressed by Kerensky: "His personality had no magnetism. He gave no feeling of intellectual or of physical vigour."

W. Somerset Maugham left the same evening for Oslo to board a British destroyer which, after a stormy passage across the North Sea, landed him in the north of Scotland. Next morning he saw Lloyd George at 10 Downing Street. After the agent told the Prime Minister what Kerensky wanted, he replied: "I can't do that. I'm afraid I must bring this conversation to an end. I have a cabinet meeting I must go to." On 7th November, 1917, Kerensky was overthrown by the Bolshevik Revolution. Maugham later recalled: "Perhaps if I had been sent to Russia six months sooner... I might have been able to do something."

After the First World War Maugham returned to writing. Another successful book, The Moon and Sixpence, was published in 1919. Maugham also developed a reputation as a fine short-story writer, one story, Rain, which appeared in The Trembling of a Leaf (1921), was also turned into a successful feature film. Popular plays written by Maugham include The Circle (1921), East of Suez (1922), The Constant Wife (1926) and the anti-war play, For Services Rendered (1932).

In his later years Maugham wrote his autobiography, Summing Up (1938) and works of fiction such as The Razor's Edge (1945), Catalina (1948) and Quartet (1949).

On this day in 1877 Lillian Mary Dugdale, the third of four children, was born to Elizabeth Moore and Alfred Dugdale in Horfield, Gloucestershire. Her father was a "Master Mariner".

On 19th August 1903, Lillian Dugdale married Arnold William Dove Willcox, an "Assistant Manager in a Leather Factory". On 8th July 1907, Arnold William Dove Willcox died, leaving effects valued at £4,799 to his widow, Lilian Mary Willcox.

After the death of her husband she joined the Women Social & Political Union in Bristol. On 29th June 1909 she was arrested after taking part in the WSPU deputation to the House of Commons and was sentenced to a month's imprisonment.

While in Holloway Prison Lilian Dove Willcox went on hunger-strike. She also assaulted a wardress and was sentenced to a further ten days' imprisonment. Mary Blathwayt recalled what happened when she was released from prison: "We drove down to Bristol station, and formed up into a procession; it was to receive Mrs. Dove Willcox and Miss Mary Allen, two ex-prisoners and hunger strikers on their return to Bristol. A military band had promised to play, but they declined at the last moment. First came a carriage containing Mrs. Dove Willcox, and Miss Mary Allen; Annie Kenney and some others walked just behind it and then followed a long procession of ladies with banners and tricolour."

In 1909 Lillian Dove Willcox worked alongside Annie Kenney, Clara Codd, Marie Naylor, Vera Holme and Elsie Howey in the West of England campaign. During this period she became a frequent visitor to Eagle House near Batheaston, the home of fellow WSPU member, Mary Blathwayt. Her father, Colonel Linley Blathwayt was sympathetic to the WSPU cause and on 10th May 1910 he planted a tree, a Picea Orientalis, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house.

On 18th November 1910, Dove Wilcox took part in a demonstration at 10 Downing Street against the failure of Herbert Asquith and his government to pass legislation to give women the vote. Votes for Women reported that 159 women and three men were arrested. This included Dove Willcox, Catherine Marshall, Eveline Haverfield, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Mary Leigh, Vera Holme, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Kitty Marion, Clara Giveen, Eileen Casey, Ada Wright and Grace Roe.

Dove Willcox replaced Annie Kenney as secretary of the Bristol branch of the WSPU in 1911. Christabel Pankhurst began useing the WSPU newspaper, Votes for Women, to advocate the hunger-strike. "The spiritual force which they are exerting is so great that prison walls are rent, prison gates forced open, and they emerge free in body as they have never for an instant ceased to be... Those who, in these latter days, are privileged to witness this triumph of the spiritual over the physical, understand the true meaning and manner of the miracles of old times." Dove Willcox agreed with this strategy and was willing to employed her home as a place where hunger-strikers, such as Mary Richardson, could recover from their ordeal.

A number of significant figures in the WSPU left the organisation over the arson campaign. This included Lillian Dove Willcox, Elizabeth Robins, Jane Brailsford, Laura Ainsworth, Eveline Haverfield and Louisa Garrett Anderson. Leaders of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage such as Henry N. Brailsford, Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman, argued "that militancy had been taken to foolish extremes and was now damaging the cause".

Some leaders of the WSPU such as Sylvia Pankhurst, disagreed with this arson campaign. In 1913, Pankhurst, with the help of Mary Dove Willcox, Keir Hardie, Norah Smyth, Julia Scurr, Mary Phillips, Millie Lansbury, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Joachim, Jessie Stephen, Nellie Cressall and George Lansbury and Zeli Emerson, established the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party.

As June Hannam has pointed out: "The ELF was successful in gaining support from working women and also from dock workers. The ELF organized suffrage demonstrations and its members carried out acts of militancy. Between February 1913 and August 1914 Sylvia was arrested eight times. After the passing of the Prisoners' Temporary Discharge for Ill Health Act of 1913 (known as the Cat and Mouse Act) she was frequently released for short periods to recuperate from hunger striking and was carried on a stretcher by supporters in the East End so that she could attend meetings and processions. When the police came to re-arrest her this usually led to fights with members of the community which encouraged Sylvia to organize a people's army to defend suffragettes and dock workers. She also drew on East End traditions by calling for rent strikes to support the demand for the vote."

Norah Smyth supplied most of the money for this venture. Appointed treasurer of the EFL she helped finance their weekly newspaper, The Women's Dreadnought that first appeared in March 1914. Although they printed 20,000 copies, by the third issue total sales were only listed as just over 100 copies. During processions and demonstrations, the newspaper was freely distributed as propaganda for the EFF and the wider movement for women's suffrage.

On 3rd June 1914, at St Pancras, London, Lillian Mary Dove-Willcox married 32-year-old journalist Reginald Ramsden Buckley. This union produced a daughter named Diana Gabrielle Buckley (1915-2008). Buckley, aged 37, died in a London hospital on 21st March 1919, leaving effects valued at £4,313.

Between 1924 and 1960, Lillian Mary Buckley lived at various addresses in Hampstead, London. When the 1939 National Register was compiled, she was residing at 156 Haverstock Hill, Hampstead, London, with her unmarried older sister Caroline Elizabeth Dugdale. In 1952, Lillian Mary Buckley was living at 15 Lyndhurst Road, Hampstead, London NW3.

Lillian Dove Willcox was living at 44 Marlborough Road, Ealing East, when she died in 1963.

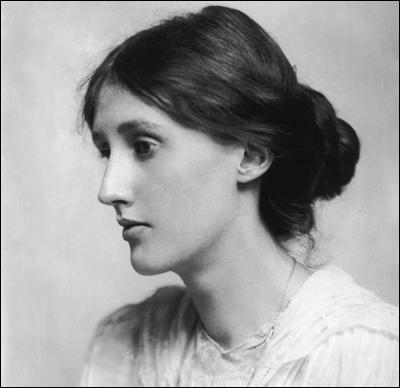

On this day in 1882 Virginia Stephen, the daughter of Leslie Stephen and Julia Princep Duckworth, was born at Hyde Park Gate, Kensington. Her father was the author of several important literary works and the editor of the The Dictionary of National Biography. Her mother had three children from her first marriage, George Duckworth (1868–1934), Stella Duckworth (1869–1897), and Gerald Duckworth (1870–1937). Virginia had a sister and two brothers: Vanessa Stephen (1879), Thoby Stephen (1880) and Adrian Stephen (1883).

According to her biographer, Lyndall Gordon: "Virginia's strongest memories from childhood were the idyll of St Ives, a basis for art, and at the other extreme, humiliation at the age of six when Gerald Duckworth, her grown-up half-brother (the younger son of her mother's first marriage), lifted her onto a ledge and explored her private parts - leaving her prey to sexual fear and initiating a lifelong resistance to certain forms of masculine authority."

When Virginia was thirteen her mother died and this brought on the first of her several breakdowns. She was very close to her sister, Vanessa Stephen. Her biographer, Vanessa Curtis, has commented: "When Vanessa was not in her art class, the sisters often spent mornings companionably closeted away in a little class room off the back of the drawing-room, almost entirely made up of windows and perfect for quiet writing and painting." Leslie Stephen held conventional views on education and unlike her two brothers, Virginia did not go to university.

In 1897 Violet Dickinson visited the home of Leslie Stephen for the first time. Stephen wrote that: "She (Violet Dickinson) has taken a great fancy to all the girls, specially to Ginia (Virginia)". In 1902 Violet began corresponding with Virginia. The two women went on holiday together to Venice, Florence and Paris. Virginia who was seventeen years her junior accused Violet of being a "dangerous woman" who was "not at all the right kind of influence over young girls". Vanessa Curtis, the author of Virginia Woolf's Women (2002) has pointed out that "Violet was full of happiness, brusque common sense, jollity and optimism, all of which were qualities much needed and admired by the young Virginia."

Virginia commented on her new friend: "She is 37 and without any pretence to good looks - which humorously she knows quite well herself and lets you know too - even going out of her way to allude laughingly to her grey hairs, and screws her face in to the most comical grimaces. But an observer who would stop here, putting her down as one of those cleverish, adaptable ladies of middle age who are welcome everywhere and not indispensable anywhere - such an observer would be superficial indeed.

Vanessa Curtis has argued that it is difficult to know if the two women had a sexual relationship. However, she points out that in July 1903 Virginia wrote to Violet that "it is astonishing what depths - what volcano depths - your finger has stirred." On another occasion Virginia told Violet that she had a double bed ready in anticipation of her visit to join her on holiday. Curtis goes on to say that "regardless of the question marks that still hang over the exact nature of their early relationship, there can be no denying that Violet was the first true emotional and physical love of Virginia's early adult life."

Leslie Stephen died of cancer on 22nd February 1904. It has been claimed that Virginia came under the control of her older stepbrother George Duckworth, who bullied and sexually abused her. With both her parents dead, Virginia became even closer to Violet Dickinson. The two women went on holiday together to Venice, Florence and Paris. Virginia who was seventeen years her junior accused Violet of being a "dangerous woman" who was "not at all the right kind of influence over young girls".

In 1904 Mary Sheepshanks, the vice-principal of Morley College for Working Men and Women, appointed Virginia to teach history evening classes. Other lecturers at the college included Graham Wallas, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson and Ernest Shepherd. Sheepshanks later recalled how much the college meant to the people in the area: "Very many of the students left home early in the morning by the workman's train, came straight from work to their classes and arrived home late, not having had any solid meal all day... It was distinctly a school for tired people."

Violet became a firm believer in Virginia's literary talent and introduced her to Margaret Littleton, the editor of the women's supplement of The Guardian . As a result of this meeting, Virginia was commissioned to write an article on Charlotte Brontë. The author of Virginia Woolf's Women (2002) has pointed out that "Violet was full of happiness, brusque common sense, jollity and optimism, all of which were qualities much needed and admired by the young Virginia."

After the death of their father Virginia and Vanessa Stephen moved to Bloomsbury. Their brother, Thoby Stephen, introduced them to some of his friends that he had met at the University of Cambridge. The group began meeting to discuss literary and artistic issues. The friends, who eventually became known as the Bloomsbury Group, included Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, David Garnett, Desmond MacCarthy, Arthur Waley and Duncan Grant. Virgina also had reviews of books published in the Times Literary Supplement.

The Stephen family went on holiday to Greece in September 1906. Violet Dickinson went with them as a self-styled "foster mother". According to Hermione Lee, the author of Virginia Woolf (1996): "For Thoby, Greece was the last long holiday before he was called to the Bar. He was full of energy and ambitions, passionately opinionated and enthusiastic." Thoby Stephen, who returned home seriously ill from typhoid, died on 20th November 1906.

Vanessa Stephen married Clive Bell on 7th February 1907. Vanessa Curtis , the author of Virginia Woolf's Women (2002) , points out that after their marriage, Clive became very close to Virginia: "Virginia, envious of her sister's newfound married happiness, also began to court favour and affection from Clive. A flirtation between the two sprang up in Cornwall, when Vanessa was too wrapped up in her first baby, Julian, to pay much attention to anyone else. Clive, flattered, and feeling shut out by his wife, reciprocated with passion and longed to make the flirtation physical; Virginia, existing cerebrally and intellectually, was happier to draw the line at long, stimulating walks and clever letters."

On 30th August, 1908, Virginia wrote to Violet Dickinson: "Supposing we drift apart, in the next three years, so that we meet and remember our ancient correspondence." Hermione Lee, the author of Virginia Woolf (1996), has argued that "Virginia's intimacy with Violet was playfully erotic from the beginning of their correspondence. The teasing jokes, the demands for attention, the confiding of secrets, were part of an extortionate appeal for petting and mothering. Violet was her woman." Lee points out that Dickinson played an important role in her writing: "She used Violet as her sounding-board for her evolving ideas about how to live, how to talk and how to write."

In December 1908, Ottoline Morrell had tea with Virginia at her home in Fitzroy Square, Bloomsbury. Virginia was impressed with Ottoline and confessed to Violet Dickinson that their relationship was like "sitting under a huge lily, absorbing pollen like a seduced bee." Vanessa believed that Ottoline was bisexual and that she was physically attracted to her sister. In her memoirs, Ottoline admitted that she was entranced by Virginia: "This strange, lovely, furtive creature never seemed to me to be made of common flesh and blood. She comes and goes, she folds her cloak around her and vanishes, having shot into her victim's heart a quiverful of teasing arrows."

in 1910 Virginia suffered another mental breakdown. That summer she spent six weeks at a private nursing home in Twickenham, which specialized in patients with nervous disorders. She was very unhappy during this period and told her sister: "I shall soon have to jump out of a window."

Later that year Clive Bell met Roger Fry in a railway carriage between Cambridge and London. Virginia later recalled: "It must have been in 1910 I suppose that Clive one evening rushed upstairs in a state of the highest excitement. He had just had one of the most interesting conversations of his life. It was with Roger Fry. They had been discussing the theory of art for hours. He thought Roger Fry the most interesting person he had met since Cambridge days. So Roger appeared. He appeared, I seem to think, in a large ulster coat, every pocket of which was stuffed with a book, a paint box or something intriguing; special tips which he had bought from a little man in a back street; he had canvases under his arms; his hair flew; his eyes glowed." From then on Fry became a very important member of the Bloomsbury Group.

Ottoline Morrell remained in close contact with Virginia, but it was always a difficult relationship. In her memoirs, Ottoline recalled: "She seemed to feel certain of her own eminence. It is true, but it is rather crushing, for I feel she is very contemptuous of other people. When I stretched out a hand to feel another woman, I found only a very lovely, clear intellect." Ottoline was fully aware of Virginia's abilities, she had "such energy and vitality and seemed to me far the most imaginative and mastery intellect that I had met for many years."

Virginia took an interest in the campaign for women's suffrage and was active briefly with the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and later joined the Adult Suffrage Society. However, her main political involvement was as a member of the Women's Co-operative Guild, a radical organisation led by Margaret Llewelyn Davies. Virginia wrote that "I went to the Women's Cooperative Guild, which pleased me by its good sense, and the evidence that it does somehow stand for something real to these women. In spite of their solemn passivity they have a deeply hidden and inarticulate desire for something beyond the daily life."

In the spring of 1911 Vanessa Bell went on holiday to Turkey with Clive Bell and Roger Fry. During her stay Vanessa had a miscarriage and a mental breakdown. Virginia went out to help nurse her. She was also going through a period of depression. She wrote: "To be 29 and unmarried - to be a failure - childless - insane too, no writer." Both Vanessa and Virginia fell in love with Fry. That summer Vanessa began an affair with Fry. They tried to keep in secret from Virginia but on 18th January 1912, Vanessa wrote to Fry: "Virginia told me last night that she suspected me of having a liaison with you. She has been quick to suspect it, hasn't she?"

The awareness that her sister was having an affair with Fry was a major influence on why Virginia decided to marry Leonard Woolf on 10th August 1912. He resigned from the colonial service after a six-and-a-half-year stint as civil servant in Ceylon. The couple embarked on a writing life at Hogarth House in Richmond and at her rented home, Asheham House, at Beddingham, near Lewes.

In 1914 Virginia Woolf had a severe mental breakdown. Leonard Woolf nursed her back to recovery and in 1915 her first novel, The Voyage Out, was published. According to Stanford Patrick Rosenbaum: "He had recognized her genius before their marriage, but not the extent of her mental instability. For nearly thirty years one of Leonard's chief occupations was caring for Virginia. Without his vigilant love, her books would never have been written; he was her first reader, her editor, and her publisher. Though not a sexually active marriage, theirs was one of profound and enduring affection."

The couple shared a strong interest in literature and in 1917 founded the Hogarth Press. Over the next few years they published the work of Flora Mayor, Katherine Mansfield, E. M. Forster, John Maynard Keynes, Robert Graves, Julia Strachey, T. S. Eliot and Edith Sitwell. They also published Virginia's Night and Day, a novel that deals with the subject of women's suffrage in 1919. This was followed by Jacob's Room (1922), a novel that tells the story of Jacob Flanders, a soldier killed in the First World War.

After the war they bought Monk's House, a cottage in Rodmell, so Virginia could be close to her sister, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, who lived at Charleston Farmhouse . In 1919 Leonard Woolf was appointed as secretary of an advisory committees on international and imperial questions that had been set-up by the Labour Party. In 1920 Woolf published Empire and Commerce in Africa, which analysed the economic imperialism of African colonization.

Virginia wrote about literature for The Nation and in an article published in December, 1923, attacked the "shallow realism" of Arnold Bennett and advocated a more "internal approach" to literature. This article was an important step in the development of what became known as Modernism. Woolf rejected the traditional framework of narrative, description and rational exposition in prose and made considerable use of the stream of consciousness technique (recording the flow of thoughts and feelings as they pass through the character's mind). This approach was explored in Virginia's novels: Mrs Dalloway (1925) and To the Lighthouse (1927).

Woolf became romantically involved with the writer, Vita Sackville-West. Her nephew, Quentin Bell, later recalled: "There may have been - on balance I think that there probably was - some caressing, some bedding together. But whatever may have occurred between them of this nature, I doubt very much whether it was of a kind to excite Virginia or to satisfy Vita. As far as Virginia's life is concerned the point is of no great importance; what was, to her, important was the extent to which she was emotionally involved, the degree to which she was in love. One cannot give a straight answer to such questions but, if the test of passions be blindness, then her affections were not very deeply engaged."

In September 1927, Sackville-West began an affair with Mary Garman, the wife of Roy Campbell, the poet. Mary wrote: "You are sometimes like a mother to me. No one can imagine the tenderness of a lover suddenly descending to being maternal. It is a lovely moment when the mother's voice and hands turn into the lover's."

Virginia Woolf was very jealous of the affair. She wrote to Vita: "I rang you up just now to find you were gone nutting in the woods with Mary Campbell... but not me - damn you." It is believed that Woolf's novel Orlando was influenced by the affair. In October 1927 Virginia wrote to Vita: "Suppose Orlando turns out to be about Vita; and its all about you and the lusts of your flesh and the lure of your mind (heart you have none, who go gallivanting down the lanes with Campbell) - suppose there's the kind of shimmer of reality which sometimes attaches to my people... Shall you mind?"

Vita Sackville-West replied that she thrilled and terrified "at the prospect of being projected into the shape of Orlando". She added: "What fun for you; what fun for me. You see, any vengeance that you want to take will be ready in your hand... You have my full permission." Orlando, was published in October 1928, with three pictures of Vita among its eight photographic illustrations. Dedicated to Vita, the novel, published in 1928, traces the history of the youthful, beautiful, and aristocratic Orlando, and explores the themes of sexual ambiguity.

After reading the book, Mary Garman wrote to Vita: "I hate the idea that you who are so hidden and secret and proud even with people you know best, should be suddenly presented so nakedly for anyone to read about... Vita darling you have been so much Orlando to me that how can I help absolutely understanding and loving the book... Through all the slight mockery which is always in the tone of Virginia's voice, and the analysis etc., Orlando is written by someone who loves you so obviously."

Virginia Woolf was also romantically involved with Katherine Mansfield. Her nephew, Quentin Bell, wrote: "Virginia felt as a lover feels - she desponded when she fancied herself neglected, despaired when Vita was away, waiting anxiously for letters, needed Vita's company and lived in that strange mixture of elation and despair which lovers - and one would have supposed only lovers - can experience. All this she has done and felt for Katherine Mansfield, but she never writes of her as she does of Vita."

A highly respected journalist and literary critic, Virginia published a series of important non-fiction books including A Room of One's Own that appeared in 1929. An important book in the history of feminism, it argues the need for the economic independence of women and explores the consequences of a male-dominated society.

Virginia Woolf's most ambitious novel, The Waves, was published in 1931. According to Lyndall Gordon: "Its framework of steel invents a revolutionary treatment of the lifespan. Here the writer is at her furthest remove from the traditional biographic schema, the public highway from pedigree to grave. Not only are there no pedigrees in The Waves; there are no placing surnames and no society to speak of, for here she explores the genetic givens of existence, unfolding what is innate in human nature against the backdrop of what is permanent in nature: sun and sea."

Woolf became increasingly interested in feminism and in her diary on 31st December, 1932, she resolved to speak out as a woman against the abuses of power. During this period began a relationship with Ethel Smyth, an activist in the Women Social & Political Union and a former lover of Emmeline Pankhurst.

Virginia Woolf had recurring bouts of depression. The outbreak of the Second World War increased her mental turmoil and Leonard Woolf arranged for Octavia Wilberforce to treat Virginia. He later recalled: "She (Octavia Wilberforce) had, to all intents and purposes become Virginia's doctor, and so the moment I became uneasy about Virginia's psychological health in the beginning of 1941 I told Octavia and consulted her professionally. The desperate difficulty which always presented itself when Virginia began to be threatened with a breakdown - a difficulty which occurs, I think, again and again in mental illness - was to decided how far it was safe to go in urging her to take steps - drastic steps - to ward off the attack."

On 28th March, 1941, Virginia wrote a letter to Leonard: "I feel certain that I am going mad again. I feel we can't go through another of those terrible times. And I shan't recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can't concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don't think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came. I can't fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can't even write this properly. I can't read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that - everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can't go on spoiling your life any longer."

Later that morning she committed suicide by drowning herself in the Ouse, near her home in Rodmell. After her body was recovered three weeks later, on 18 April, Leonard Woolf buried her ashes in the Monk's House garden.

On this day in 1890 Nellie Bly completes her round-the-world journey in 72 days. Elizabeth Cochrane was born in Cochran Mills, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, on 5th May, 1867. Her father died six years later, leaving her mother, Mary Jane Cochrane, with fifteen children to raise. Elizabeth was not an impressive student at school but she did develop a strong desire to be a writer.

The family were fairly poor and when Elizabeth reached sixteen she moved to Pittsburgh to find work. She soon discovered that only low-paid occupations were available to women. In 1885 she read an article in the Pittsburgh Dispatch entitled What Girls Are Good For. The male writer argued that women were only good for housework and taking care of children. Elizabeth was furious and wrote a letter of protest to the editor. George Madden responded by asking her what articles she would write if she was a journalist. She replied that newspapers should be publishing articles that told the stories of ordinary people. As a result of her letter, Madden commissioned Elizabeth, who was only eighteen, to write an article on the lives of women.

Elizabeth accepted, but as it was considered improper for at the time for women journalists to use their real names, she used a pseudonym: Nellie Bly. She decided to write an article on divorce based on interviews with women that she knew. In the piece, Bly used the material to argue for the reform of the marriage and divorce laws. Madden was so impressed with the article he hired her as a full-time reporter for the Pittsburgh Dispatch. Bly's journalistic style was marked by her first-hand tales of the lives of ordinary people. She often obtained this material by becoming involved in a series of undercover adventures. For example, she worked in a Pittsburgh factory to investigate child labour, low wages and unsafe working conditions. Bly was not only interested in writing about social problems but was always willing to suggest ways that they could be solved.

Madden later wrote that Nellie Bly was "full of fire and her writing was charged with youthful exuberance." However, it was not long before he was receiving complaints from those institutions that Bly was attacking in her articles. When companies began threatening to stop buying advertising space in the Pittsburgh Dispatch, the editor was forced to bring an end to the series.

Nellie Bly was now given cultural and social events to cover. Unhappy with this new job, Bly decided to go to Mexico where she wrote about poverty and political corruption. When the Mexican government discovered what Bly had been writing, they ordered her out of the country. Her account of life in Mexico was later published as Six Months in Mexico (1888). It included the followed: "The constitution of Mexico is said to excel, in the way of freedom and liberty to its subjects, that of the United States; but it is only on paper. It is a republic only in name, being in reality the worst monarchy in existence. Its subjects know nothing of the delights of a presidential campaign; they are men of a voting age, but they have never indulged in this manly pursuit, which even our women are hankering after. No two candidates are nominated for the position, but the organized ring allows one of its members - whoever has the most power - to say who shall be president."

In 1887 Bly was recruited by Joseph Pulitzer to write for his newspaper, the New York World. Over the next few years she pioneered the idea of investigative journalism by writing articles about poverty, housing and labour conditions in New York. This often involved undercover work and she feigned insanity to get into New York's insane asylum on Blackwell's Island.

Bly later wrote in Ten Days in a Mad House (1888): "Excepting the first two days after I entered the asylum, there was no salt for the food. The hungry and even famishing women made an attempt to eat the horrible messes. Mustard and vinegar were put on meat and in soup to give it a taste, but it only helped to make it worse. Even that was all consumed after two days, and the patients had to try to choke down fresh fish, just boiled in water, without salt, pepper or butter; mutton, beef, and potatoes without the faintest seasoning. The most insane refused to swallow the food and were threatened with punishment. In our short walks we passed the kitchen where food was prepared for the nurses and doctors. There we got glimpses of melons and grapes and all kinds of fruits, beautiful white bread and nice meats, and the hungry feeling would be increased tenfold. I spoke to some of the physicians, but it had no effect, and when I was taken away the food was yet unsalted."

Bly discovered while staying in the hospital that patients were fed vermin-infested food and physically abused by the staff. She also found out that some patients were not psychologically disturbed but were suffering from a physical illness. Others had been maliciously placed there by family members. For example, one woman had been declared insane by her husband after he caught her being unfaithful. Bly's scathing attacks on the way patients were treated at Blackwell's Island led to much needed reforms.

After reading Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days in 1889, Bly suggested to Joseph Pulitzer that his newspaper should finance an attempt to break the record illustrated in the book. He liked the idea and used Bly's journey to publicize the New York World. The newspaper held a competition which involved guessing the time it would take Bly to circle the globe. Over 1,000,000 people entered the contest and when she arrived back in New York on 25th January, 1890, she was met by a massive crowd to see her break the record in 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes and 14 seconds.

Bly retired from journalism after marrying Robert Seaman in 1895. Seaman, the millionaire owner of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company and the American Steel Barrel Company, died in 1904. Bly decided to take over the running of these two ailing companies. Recognizing the importance of the well-being of the workers, Bly introduced a series of reforms that included the provision of health-care schemes, gymnasiums and libraries.

Bly was on holiday in Europe on the outbreak of the First World War. She immediately travelled to the Eastern Front where she reported the war for the New York Journal American.

Nellie Bly died of pneumonia at St. Mark's Hospital in New York City on 27th January, 1922. She was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.