Ada Wright

Ada Cecile Granville Wright, the daughter of James Wright (1826-1896) and Sarah Jane Massey (1826-1907), was born in Manche, Normandy, in northwestern France, on 9th February 1861. Ada was the third of five children: Agnes Gertrude Wright (1857–1939), Florence Maud Wright (1859–1928), Blanche Eleanor Anne Wright (1863–1950) and Albert Evelyn Wright (1864–1930). Ada's father, James Wright, was a successful importer of American goods. (1)

Wright attended the Slade School of Fine Art and University College London, where she was taught English Literature by the socialist activist, Edward Aveling, the partner of Eleanor Marx, the daughter of Karl Marx. (2)

Wright wanted to became a social worker, but at the time was prevented in doing so by her father. Although she accepted her father's instructions she became interested in the subject of women's rights and commented that she "wished I had been born a boy." Wright was described as "one of those quiet women whose gentle and calm manner hides a courageous and indomitable nature of unexpected depths." (3)

Ada Wright: Women's Suffrage Campaigner

The family moved to Sidmouth and in 1885 her father eventually agreed for her to to join the local settlement house. During this period she helped young people from the local workhouse to find "suitable employment". (4) She also joined the National Union of Suffrage Societies. Later she moved to London and run a club for working-class girls in Soho. She also had a spell as a probationer nurse at the London Hospital. (5)

Ada's father, James Wright, died in 1896, leaving £40,944 to his family. By 1901, Ada Wright was residing with her widowed mother and her three unmarried sisters (Agnes, Florence & Blanche) at "Rushmore", Branksome Road, Bournemouth. (6)

In October 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst decided to establish the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Emmeline stated that the main aim of the organisation was to recruit women into the struggle for the vote. "We resolved to limit our membership exclusively to women, to keep ourselves absolutely free from any party affiliation, and to be satisfied with nothing but action on our question. Deeds, not words, was to be our permanent motto." (7)

The main objective was to gain, not universal suffrage, the vote for all women and men over a certain age, but votes for women, “on the same basis as men.” This meant winning the vote not for all women but for only the small stratum of women who could meet the property qualification. As one critic suggested, it was "not votes for women", but “votes for ladies.” As an early member of the WSPU, Dora Montefiore, pointed out: "The work of the Women’s Social and Political Union was begun by Mrs. Pankhurst in Manchester, and by a group of women in London who had revolted against the inertia and conventionalism which seemed to have fastened upon... the NUWSS." (8)

Conciliation Bill

Ada Wright, who frustrated by the lack of progress made by the National Union of Suffrage Societies who now considered the organisation as being "ineffective for making the question of justice to women a living force." Ada decided to join and devote all her time the WSPU and volunteered for "pavement chalking, unpaid clerical work at Clement's Inn and campaigning at by-elections." (9)

Wright was arrested for the first time in 1907. (10) In October 1908 she was arrested for obstructing the police at the House of Commons. (11) On 29th June, 1909, Ada Wright and Sarah Carwin were arrested for breaking government windows. They were sentenced to a month in prison. While in Holloway they broke every window in their cells as a protest. (12) Both women were released after being on hunger strike for six days. (13)

In January 1910, H. H. Asquith called a general election in order to obtain a new mandate. However, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Henry Brailsford, a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage wrote to Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Woman's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), suggesting that he should attempt to establish a Conciliation Committee for Women's Suffrage. "My idea is that it should undertake the necessary diplomatic work of promoting an early settlement". (14)

Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) agreed to the idea and they declared a truce in which all militant activities would cease until the fate of the Conciliation Bill was clear. A Conciliation Committee, composed of 36 MPs (25 Liberals, 17 Conservatives, 6 Labour and 6 Irish Nationalists) all in favour of some sort of women's enfranchisement, was formed and drafted a Bill which would have enfranchised only a million women but which would, they hoped, gain the support of all but the most dedicated anti-suffragists. (15) Fawcett wrote that "personally many suffragists would prefer a less restricted measure, but the immense importance and gain to our movement is getting the most effective of all the existing franchises thrown upon to woman cannot be exaggerated." (16)

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. However, when Keir Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party, requested two hours to discuss the Conciliation Bill, Asquith made it clear that he intended to shelve it. (17)

18th November 1910

Emmeline Pankhurst was furious at what she saw as Asquith's betrayal and on 18th November, 1910, arranged to lead 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. Pankhurst and a small group of WSPU members, were allowed into the building but Asquith refused to see them. Women, in "detachments of twelve" marched forward but were attacked by the police. (18)

Votes for Women reported that 159 women and three men were arrested during this demonstration. (19) This included Ada Wright, Catherine Marshall, Eveline Haverfield, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Mary Leigh, Vera Holme, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Kitty Marion, Clara Giveen, Eileen Casey, Lilian Dove-Wilcox and Grace Roe. (20)

Sylvia Pankhurst later described what happened: "As, one after the other, small deputations of twelve women appeared in sight they were set upon by the police and hurled aside. Mrs Cobden Sanderson, who had been in the first deputation, was rudely seized and pressed against the wall by the police, who held her there by both arms for a considerable time, sneering and jeering at her meanwhile.... Just as this had been done, I saw Miss Ada Wright close to the entrance. Several police seized her, lifted her from the ground and flung her back into the crowd. A moment afterwards she appeared again, and I saw her running as fast as she could towards the House of Commons. A policeman struck her with all his force and she fell to the ground. For a moment there was a group of struggling men round the place where she lay, then she rose up, only to be flung down again immediately. Then a tall, grey-headed man with a silk hat was seen fighting to protect her; but three or four police seized hold of him and bundled him away. Then again, I saw Miss Ada Wright's tall, grey-clad figure, but over and over again she was flung to the ground, how often I cannot say. It was a painful and degrading sight. At last, she was lying against the wall of the House of Lords, close to the Strangers' Entrance, and a number of women, with pale and distressed faces were kneeling down round her. She was in a state of collapse." (21)

Several women reported that the police dragged women down the side streets. "We knew this always meant greater ill-usage.... The police snatched the flags, tore them to shreds, and smashed the sticks, struck the women with fists and knees, knocked them down, some even kicked them, then dragged them up, carried them a few paces and flung them into the crowd of sightseers." It was claimed that two women, Cecilia Haig and Henria Williams, died because of the beatings they endured that day. "I saw Celilia Haig go out with the rest; a tall, strongly built, reserved woman, comfortably situated, who in ordinary circumstances might have gone through life without receiving an insult, much less a blow. She was assaulted with violence and indecency, and died in December 1911, after a painful illness, arising from her injuries. Henria Williams, already suffering from a weak heart, did not recover from the treatment she received that night in the Square, and died on January 1st." (22)

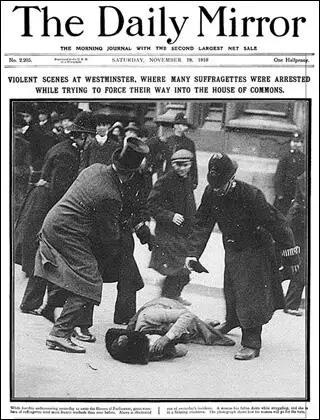

The photograph of Ada Wright on the front page of The Daily Mirror the next day caused a great deal of embarrassment to the Home Office and the government demanded that the negative be destroyed. (23) Wright told a reporter that she had been at seven suffragette demonstrations, but had "never known the police so violent." (24) Charles Mansell-Moullin, who had helped treat the wounded claimed that the police had used "organised bands of well-dressed roughs who charged backwards and forwards through the deputations like a football team without any attempt being made to stop them by the police." (25)

Sylvia Pankhurst believed that Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary, had encouraged this show of force. "Never, in all the attempts which we have made to carry our deputations to the Prime Minister, have I seen so much bravery on the part of the women and so much violent brutality on the part of the policeman in uniform and some men in plain clothes. It was at the same time a gallant and a heart-breaking sight to see those little deputations battling against overwhelming odds, and then to see them torn asunder and scattered, bruised and battered, against the organized gangs of rowdies. Happily, there were many true-hearted men in the crowd who tried to help the women, and who raised their hats and cheered them as they fought. I found out during the evening that the picked men of the A Division, who had always hitherto been called out on such occasions, were this time only on duty close to the House of Commons and at the police station, and that those with whom the women chiefly came into contact had been especially brought in from the outlying districts. During our conflicts with the A Division they had gradually come to know us, and to understand our aims and objects, and for that reason, whilst obeying their orders, they came to treat the women, as far as possible, with courtesy and consideration. But these men with whom we had to deal on Friday were ignorant and ill-mannered, and of an entirely different type. They had nothing of the correct official manner, and were to be seen laughing and jeering at the women whom they maltreated." (26)

Churchill had been a long-term opponent of votes for women. As a young man he argued: "I shall unswervingly oppose this ridiculous movement (to give women the vote)... Once you give votes to the vast numbers of women who form the majority of the community, all power passes to their hands." His wife, Clementine Churchill, was a supporter of votes for women and after marriage he did become more sympathetic but was not convinced that women needed the vote. When a reference was made at a dinner party to the action of certain suffragettes in chaining themselves to railings and swearing to stay there until they got the vote, Churchill's reply was: "I might as well chain myself to St Thomas's Hospital and say I would not move till I had had a baby." However, it was the policy of the Liberal Party to give women the vote and so he could not express these opinions in public. (27)

Henry Brailsford was commissioned to write a report on the way that the police dealt with the demonstration. He took testimony from a large number of women, including Mary Frances Earl: "In the struggle the police were most brutal and indecent. They deliberately tore my undergarments, using the most foul language - such language as I could not repeat. They seized me by the hair and forced me up the steps on my knees, refusing to allow me to regain my footing... The police, I understand, were brought specially from Whitechapel." (28)

Paul Foot, the author of The Vote (2005) has pointed out, Brailsford and his committee obtained "enough irrefutable testimony not just of brutality by the police but also of indecent assault - now becoming a common practice among police officers - to shock many newspaper editors, and the report was published widely". (29) However, Edward Henry, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, claimed that the sexual assaults were committed by members of the public: "Amongst this crowd were many undesirable and reckless persons quite capable of indulging in gross conduct." (30)

1911 Conciliation Bill

Under pressure from the National Union of Suffrage Societies and the Women's Social and Political Union and the in 1911 the Liberal government introduced the Conciliation Bill that was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. According to Lucy Masterman, it was her husband, Charles Masterman, who provided the arguments against the legislation: "He (Churchill) is, in a rather tepid manner, a suffragist (his wife is very keen) and he came down to the Home Office intending to vote for the Bill. Charlie, whose sympathy with the suffragettes is rather on the wane, did not want him to and began to put to him the points against Shackleton's Bill - its undemocratic nature, and especially particular points, such as that 'fallen women' would have the vote but not the mother of a family, and other rhetorical points. Winston began to see the opportunity for a speech on these lines, and as he paced up and down the room, began to roll off long phrases. By the end of the morning he was convinced that he had always been hostile to the Bill and that he had already thought of all these points himself...He snatched at Charlie's arguments against this particular Bill as a wild animal snatches at its food." (31)

Winston Churchill argued in the House of Commons: "The more I study the Bill the more astonished I am that such a large number of respected Members of Parliament should have found it possible to put their names to it. And, most of all, I was astonished that Liberal and Labour Members should have associated themselves with it. It is not merely an undemocratic Bill; it is worse. It is an anti-democratic Bill. It gives an entirely unfair representation to property, as against persons.... Of the 18,000 women voters it is calculated that 90,000 are working women, earning their living. What about the other half? The basic principle of the Bill is to deny votes to those who are upon the whole the best of their sex. We are asked by the Bill to defend the proposition that a spinster of means living in the interest of man-made capital is to have a vote, and the working man's wife is to be denied a vote even if she is a wage-earner and a wife.... What I want to know is how many of the poorest class would be included? Would not charwomen, widows, and others still be disfranchised by receiving Poor Law relief? How many of the propertied voters will be increased by the husband giving a £10 qualification to his wife and five or six daughters?" (32)

David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was officially in favour of woman's suffrage. However, he was convinced that the chief effect of the Bill, if it became law, would be to hand more votes to the Conservative Party. During the debate on the Conciliation Bill he stated that justice and political necessity argued against enfranchising women of property but denying the vote to the working class. The following day Asquith announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise the four million men currently excluded from voting and suggested it could be amended to include women. Paul Foot has pointed out that as the Tories were against universal suffrage, the new Bill "smashed the fragile alliance between pro-suffrage Liberals and Tories that had been built on the Conciliation Bill." (33)

Millicent Fawcett still believed in the good faith of the Asquith government. However, the WSPU, reacted very differently: "Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst had invested a good deal of capital in the Conciliation Bill and had prepared themselves for the triumph which a women-only bill would entail. A general reform bill would have deprived them of some, at least, of the glory, for even though it seemed likely to give the vote to far more women, this was incidental to its main purpose." (34)

Christabel Pankhurst wrote in Votes for Women that Lloyd George's proposal to give votes to seven million instead of one million women was, she said, intended "not, as he professes, to secure to women a larger measure of enfranchisement but to prevent women from having the vote at all" because it would be impossible to get the legislation passed by Parliament. (35)

On 9th November 1911, the WSPU withdrew support for the Conciliation Bill. On 21st November, the WSPU carried out an "official" window smash along Whitehall and Fleet Street. This involved the offices of the Daily Mail and the Daily News and the official residences or homes of leading Liberal politicians such as H. H. Asquith, David Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, Edward Grey, John Burns and Lewis Harcourt. It was reported that "160 suffragettes were arrested, but all except those charged with window-breaking or assault were discharged." (36)

In March 1912 she was arrested with Sarah Carwin, Olive Wharry and Kitty Marion and "charged with the wanton destruction of private property, value £4,000 and was sentenced to six months imprisonment. (37) Wright was one of those arrested for breaking Harcourt's windows in Berkeley Square. It was the fifth time in her suffragette career. Ada was sent to prison for two weeks; she wrote to a friend that the night before taking part in any militant event "the suspense always tries me terribly". (38)

Wright was accused of breaking windows of the Great Northern Railway Company in Charing Cross causing £9 worth of damage. This time she was sentenced to six months in Aylesbury Prison. (35) After going on hunger strike the prison doctor tried to put the feeding tube in her mouth Ada "clenched her teeth to prevent the tube from being pushed into her mouth". A steel gag was then used to prise open her jaws "and the tube was rammed down her throat by clumsy and unskilled fingers". Ada thought she would suffocate as this process made it difficult to breathe. This happened twice a day for ten days. Ada later recalled the wardresses being very distressed and often in tears having to help the doctor in his "gruesome task". (39)

Later Life

On 14th June 1913, Ada Wright sailed to the United States on RMS Carmania, to visit her brother Albert Evelyn Wright, who was living in Plainview, New Jersey. On her arrival she gave her occupation as "Women's Suffrage". (40)

During the First World War she groomed post office horses, worked in canteens and drove hospital and drove hospital ambulances. After the war she was a social worker and on 18th June 1928 was a pall-bearer at the funeral of Emmeline Pankhurst. In the 1930s she cared for refugees who had fled from Nazi Germany. (41)

Ada Cecile Granville Wright was living at 61 Granville Road, Finchley, when she died on 4th December 1939. She left effects valued at £24,580. (42)

Primary Sources

(1) David Simkin, Family History Research (3rd June, 2020)

Ada Cecile Granville Wright was born in Granville, Manche, Normandy, in northwestern France, on 9th February 1861, the daughter of Sarah Jane Massey (1826-1907) and James Wright (1826-1896), a merchant in American goods. (Date of birth given on Baptism Register St Thomas Church, Camden Town, completed on 19th January, 1876). Although born in France, Ada was a 'British Subject' - her father originated from Chesterfield, Derbyshire, and her mother was also from Derbyshire. When James Wright married on 9th August 1856, he gave his occupation as " Merchant ". His bride Sarah Jane Massey was the daughter of Sampson Massey, a farmer of Swarkestone, South Derbyshire.

Ada Cecile Granville Wright was the third of five children - four girls: Agnes Gertrude Wright (1857–1939),

Florence Maud Wright (1859–1928), Ada Cecile Granville Wright (1861–1939), Blanche Eleanor Anne Wright (1863–1950), and one boy, Albert Evelyn Wright (1864–1930). None of the sisters married but her brother Albert Evelyn Wright married twice. At a young age, Albert Evelyn Wright went to live in America, settling in New York City. He was naturalized as an American citizen in 1904. He married both of his wives in the United States. After the death of his second wife in 1929, Albert returned to England and settled in Golders Green, London. He died in Hendon in 1930 and is buried in Finchley.When Ada's father, James Wright, died in 1896, he had effects worth £40,944. At the time of the 1901 Census, Ada Cecile Granville Wright was residing with her widowed mother and her three unmarried sisters (Agnes, Florence & Blanche) at "Rushmore", Branksome Road, Bournemouth.

Ada Cecile Granville Wright does not give her occupation or profession in the census forms of 1881, 1891 or 1901.

September 1939 Ada Cecile Granville Wright was living at 61 Granville Road, Finchley: The accommodation was part of the Wright-Kingsford Home founded by her sister Blanche Eleanor Wright. When she died in Finchley, on 4th December 1939, Ada Cecile Granville Wright left effects valued at £24,580.

14th June 1913 sailed to the United States Liverpool to New York Ship name: Carmania , Visiting brother in Plainview New Jersey.

(2) Aberdeen Press and Journal (22 July 1909)

Release of Hunger Strikers – Miss Carwin and Miss Ada Wright two of the suffragist hunger strikers, were released from Holloway Prison yesterday. They feared for just over six days. This makes 600 hunger strikers released.

(3) Votes for Women (2nd July 1909)

Miss Ada C. Wright comes of a family that has always worked for the public good. She herself since she left school has devoted years of voluntary work to public objects. Both in canvassing for men and assisting Poor-law youths to suitable employment she realised that men will accept a woman's help in everything, and yet deny her the simple justice of the vote. This experience led her to throw herself into the Suffrage movement, and she was imprisoned for the cause in 1907 and again in 1908.

(4) Exmouth Journal (30 March 1912)

The women were charged with the wanton destruction of private property, value £4,000 on March 1st and March 4 th . The following sentences were passed. Six months: Grace Stuart, Ada Wright, Aileen O'Connor Smith, Brita Gurney, Mrs Emily Duval, Evelyn Huddestone, Sarah Carwin, Bertha Ryland, Olive Wharry, Isabella Potbury, Kitty Marion and Jeanette Green.

(5) Sylvia Pankhurst, Votes for Women (25th November 1910)

As, one after the other, small deputations of twelve women appeared in sight they were set upon by the police and hurled aside. Mrs Cobden Sanderson, who had been in the first deputation, was rudely seized and pressed against the wall by the police, who held her there by both arms for a considerable time, sneering and jeering at her meanwhile.

At first the crowds had pressed up close to the House in all directions, but after a fierce struggle the police drove them back and drew up their cordons so as to keep a clear space from the corner of Palace Yard to the Strangers' Entrance.

Just as this had been done, I saw Miss Ada Wright close to the entrance. Several police seized her, lifted her from the ground and flung her back into the crowd. A moment afterwards she appeared again, and I saw her running as fast as she could towards the House of Commons. A policeman struck her with all his force and she fell to the ground. For a moment there was a group of struggling men round the place where she lay, then she rose up, only to be flung down again immediately. Then a tall, grey-headed man with a silk hat was seen fighting to protect her; but three or four police seized hold of him and bundled him away. Then again, I saw Miss Ada Wright's tall, grey-clad figure, but over and over again she was flung to the ground, how often I cannot say. It was a painful and degrading sight. At last, she was lying against the wall of the House of Lords, close to the Strangers' Entrance, and a number of women, with pale and distressed faces were kneeling down round her. She was in a state of collapse.

The same kind of treatment was meted out to other women. I saw one tall woman in a white coat hit about the head and knocked down several times. Close to where my car was standing two young girls with linked arms were being dragged about by two policemen, and a man in plain clothes came up and kicked one of them, whilst a number of others stood by and jeered.

Never, in all the attempts which we have made to carry our deputations to the Prime Minister, have I seen so much bravery on the part of the women and so much violent brutality on the part of the policeman in uniform and some men in plain clothes. It was at the same time a gallant and a heart-breaking sight to see those little deputations battling against overwhelming odds, and then to see them torn asunder and scattered, bruised and battered, against the organized gangs of rowdies. Happily, there were many true-hearted men in the crowd who tried to help the women, and who raised their hats and cheered them as they fought.

I found out during the evening that the picked men of the A Division, who had always hitherto been called out on such occasions, were this time only on duty close to the House of Commons and at the police station, and that those with whom the women chiefly came into contact had been especially brought in from the outlying districts. During our conflicts with the A Division they had gradually come to know us, and to understand our aims and objects, and for that reason, whilst obeying their orders, they came to treat the women, as far as possible, with courtesy and consideration. But these men with whom we had to deal on Friday were ignorant and ill-mannered, and of an entirely different type. They had nothing of the correct official manner, and were to be seen laughing and jeering at the women whom they maltreated.