On this day on 19th January

On this day in 1661 Thomas Venner was executed. Thomas Venner was probably born in Littleham, Devon, in about 1608. By 1633 he had moved to London, where he worked as a cooper and became a member of the Coopers' Company. Venner emigrated to Salem, Massachusetts, in 1638 where he was allocated 40 acres. A juryman in 1638 and 1640, he married Alice and his son Thomas was born in 1641. The following year he served as constable. He spent time in Providence Island in the West Indies, but in 1644 he returned to America and settled in Boston. His wife gave birth to two more children, Hannah (b. February 1645) and Samuel (b. February 1650). Venner became a member of the artillery company in 1645 and in October 1648 he organized the coopers of Boston and Charlestown into a trading company.

After the execution of Charles I on 30th January 1649, Venner returned to England. Following the English Civil War groups such as the Levellers, Diggers and the Fifth Monarchists began to demand political reforms. Venner became a Fifth Monarchist. They argued that the king's death was a prophetic moment, signalling the coming of the new millennium and the reign of Christ and the saints on earth. This was as a result of their close reading of the prophecies of the Book of Daniel, in which the fall of the four earthly empires (Assyrian, Persian, Greek and Roman) would be followed by the rule of "King Jesus" and his saints.

Oliver Cromwell was opposed to these groups and their leaders such as John Lilburne were imprisoned. Soldiers continued to protest against the government. The most serious rebellion took place in London. Troops commanded by Colonel Edward Whalley were ordered from the capital to Essex. A group of soldiers led by Robert Lockyer, refused to go and barricaded themselves in The Bull Inn near Bishopsgate, a radical meeting place. A large number of troops were sent to the scene and the men were forced to surrender. The commander-in-chief, General Thomas Fairfax, ordered Lockyer to be executed.

Lockyer's funeral on Sunday 29th April, 1649, proved to be a dramatic reminder of the strength of the Leveller organization in London. "Starting from Smithfield in the afternoon, the procession wound slowly through the heart of the City, and then back to Moorfields for the interment in New Churchyard. Led by six trumpeters, about 4000 people reportedly accompanied the corpse. Many wore ribbons - black for mourning and sea-green to publicize their Leveller allegiance. A company of women brought up the rear, testimony to the active female involvement in the Leveller movement. If the reports can be believed there were more mourners for Trooper Lockyer than there had been for the martyred Colonel Thomas Rainsborough the previous autumn."

By 1655 Venner was employed as a master cooper in the Tower, but he was arrested in June and dismissed for allegedly discussing the possible assassination of Oliver Cromwell. (6) The government did not take him very seriously, for he was free by winter, when he participated in meetings with other Fifth Monarchists, including John Portman and Arthur Squibb, and republicans such as John Okey and the naval officer John Lawson. It is claimed that the men discussed A Healing Question (1656) that had been written by Henry Vane. The pamphlet argued for civil and religious liberty.

It was the starting point for their discussions about possible joint political action, but they failed to achieve substantive agreement. Okey, Lawson, Portman, and others were arrested in the summer, and officials were searching for Venner. In early August he was holding meetings of his Fifth Monarchist congregation at Swan Alley, Coleman Street, London; copies of Englands Remembrancers, "urging the godly to elect proponents of the Good Old Cause to parliament, were distributed."

In April 1657 he planned a rising that was backed by a manifesto, a flag that depicted a red lion and the motto "Who shall rouse him up?" The rebels intended to rendezvous at Mile End Green and then march into East Anglia, where they expected many recruits to join them. Venner and about 25 other men were arrested in London before "their plans for a theocracy and government according to biblical lore had been put to much of a test." Venner was sent to prison again, without a trial, and by the time Charles II was restored to the throne he was free once more. "His zeal was undimmed, possibly because no one seemed to take him seriously enough to prosecute him for what were undoubtedly treasonous acts."

It has been claimed that Major General Thomas Harrison and John Carew were supporters of the Fifth Monarchists. (10) On the Restoration Harrison was an obvious target for the Royalists. Harrison refused to flee the country and was therefore like other Regicides arrested and brought to the Tower of London. At his trial in October 1660 he asserted that he had acted in the name of the parliament of England and by their authority. "Maybe I might be a little mistaken, but I did it all according to the best of my understanding, desiring to make the revealed will of God in his holy scriptures as a guide to me".

Harrison claimed he had been acting on the authority of the House of Commons: Denzil Holles rejected this argument. "You do very well know that this that you did, this horrid, detestable act which you committed, could never be perfected by you till you had broken the Parliament. That House of Commons, which you say gave you authority, you know what yourself made of it when you pulled out the speaker; therefore do not make the Parliament to be the author of your black crimes."

Harrison was found guilty of treason and was sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. On 13th October 1660 he was taken on a sledge to Charing Cross, the place of his execution. On the way to his execution, Harrison said: "I go to suffer upon the account of the most glorious cause that ever was in the world." Harrison said on the scaffold: "Gentleman, by reason of some scoffing, that I do hear, I judge that some do think I am afraid to die... I tell you no, but it is by reason of much blood I have lost in the wars, and many wounds I have received in my body which caused this shaking and weakness in my nerves."

Venner responded to death of Harrison and the other Regicides by producing a new manifesto, A Door of Hope, that called his followers to arms, urging them not to sheath their swords until the monarchy had been destroyed. It called for an international crusade, financed by expropriated property, to defeat France, Spain, the Catholic states in Germany, and the papacy, and for a godly society free of poverty, taxation, primogeniture, and capital punishment for theft.

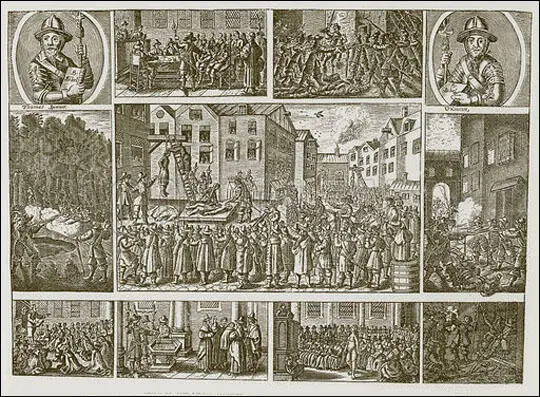

Thomas Venner and about 50 of his supporters carried flags emblazoned with King Jesus, and the "regicides' heads upon the gates" temporarily seized St Paul's, before retreating to Aldersgate. The rebels fought in a skirmish early on Wednesday morning near Leadenhall Street. Venner later claimed he had killed at least three of the approximately twenty loyalists who died. The Vennerites suffered comparable losses, and Venner himself sustained nineteen wounds.

Arraigned at the Old Bailey on the 17th, he initially refused to plead, instead launching into a discourse on the Fifth Monarchy. After finally pleading not guilty, he admitted having participated in the insurrection, but not as leader, for that had been Jesus's role. As Venner prepared to be hanged, drawn, and quartered before his meeting-house on 19 January 1661, he remained defiant, claiming to have acted "according to the best light I had, and according to the best understanding that the Scripture will afford".

By 21 January thirteen of his compatriots had been executed, and the government demolished his meeting-house. Their heads were stuck up on London Bridge as a warning to others who might attempt similar rebellious acts. As Richard L. Greaves has pointed out: If the revolt was pathetic and desperate, as some historians have suggested, it was also a manifestation of Venner's fierce conviction that Christ's people, their triumph assured, were literally to take the field against the forces of Antichrist. Resolute in his faith, Venner was a misguided millenarian zealot."

Two days after Venner's execution George Fox and eleven other Quakers issued what latter became known as the "Peace Testimony". The signers did not include militants such as Edward Burrough and Thomas Salthouse. The statement said it wanted to remove "the ground of jealously and suspicion" regarding "the harmless and innocent people of God, called Quakers." It then went on to argue: "We utterly deny all outward wars and strife and fightings with outward weapons, for any end, or under any pretence whatsoever; and this is our testimony to the whole world. The spirit of Christ, by which we are guided, is not changeable, so as once to command us from a thing as evil and again to move unto it; and we do certainly know, and so testify to the world, that the spirit of Christ, which leads us into all Truth, will never move us to fight and war against any man with outward weapons, neither for the kingdom of Christ, nor for the kingdoms of this world."

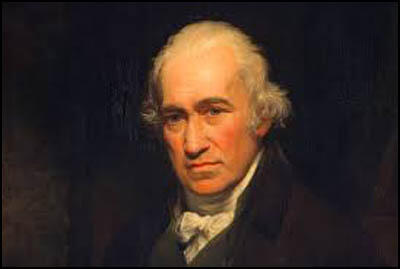

On this day in 1736 James Watt, the eldest surviving child of eight children, five of whom died in infancy, of James Watt (1698–1782) and his wife, Agnes Muirhead (1703–1755), was born in Greenock. His father was a successful merchant.

According to his biographer, Jennifer Tann: "James Watt was a delicate child and suffered from frequent headaches during his childhood and adult life. He was taught at home by his mother at first, then was sent to M'Adam's school in Greenock. He later went to Greenock grammar school where he learned Latin and some Greek but was considered to be slow. However, on being introduced to mathematics, he showed both interest and ability."

At the age of nineteen he was sent to Glasgow to learn the trade of a mathematical-instrument maker. After spending a year in London, Watt returned to Scotland in 1757 where he established his own instrument-making business. Watt soon developed a reputation as a high quality engineer and was employed on the Forth & Clyde Canal and the Caledonian Canal. He was also engaged in the improvement of harbours and in the deepening of the Forth, Clyde and other rivers in Scotland.

James Watt became very interested in the subject of steam power. In 1761 he got hold of a steam digester, a type of pressure cooker with a safety valve. It had been created by Denis Papin, a French mathematician. He looked at ways of improving the machine. He fixed an ordinary apothecary's syringe to the valve, and put a little piston inside it with a rod pointing out of the top. Between digester and syringe he fitted a steam cock which he could turn so that the steam either filled the syringe or escaped.

Thomas Savery had also tried to improve Papin's machine. One of the major problems of mining for coal, iron, lead and tin in the 17th and 18th centuries was flooding. Miners used several different methods to solve this problem. These included pumps worked by windmills and teams of men and animals carrying endless buckets of water. Savery used Papin's idea of using a cylinder and a piston to design a pumping engine which incorporated two different ways of utilizing steam to generate power. Steam was pumped into a cylinder and then cooled so that a vacuum was formed and atmospheric pressure drew water up.

On 25th July 1698 Thomas Savery obtained a patent for fourteen years. The patent contained no description of the machine, but in June 1699 it was shown to members of the Royal Society. Savery established a workshop at Salisbury Court, London. At this workshop, mine and colliery owners could see the engine demonstrated before purchase. However, the engine could not raise water from very deep mines. Another disadvantage was its tendency to cause explosions.

In 1763 Watt was sent a steam engine produced by Thomas Newcomen to repair. Newcomen, an inventor from Dartmouth , had also attempted to improve on the machines produced by Papin and Savery. He eventually came up with the idea of a machine that would rely on atmospheric air pressure to work the pumps, a system which would be safe, if rather slow. The "steam entered a cylinder and raised a piston; a jet of water cooled the cylinder, and the steam condensed, causing the piston to fall, and thereby lift water."

As Jenny Uglow has pointed out: "Newcomen's engines exploited basic atmospheric pressure, building on the way had been found to rush into a vacuum. A vacuum could be created by sucking air out of a closed vessel with a pump, but it could also be created by using steam."

Newcomen and his partner, John Calley, produced their first steam engine in 1710. John Theophilus Desaguliers points out: "In the latter end of the year 1711 made proposals to draw the water at Griff, in Warwickshire; but their invention meeting not with reception... after a great many laborious attempts, they did make the engine work; but not being either philosophers to understand the reason, or mathematicians enough to calculate the powers and to proportion the parts, very luckily by accident found what they sought for."

The steam-engine was set up next to the mine it was draining. It had a large, rocking overhead beam. From one end hung a chain which was attached to the top of a piston encased in a cylinder. According to Gavin Weightman, the author of The Industrial Revolutionaries (2007), Newcomen and Calley had "devised and brought to efficient working order was the first really reliable steam engine in the world".

Following the undoubted success of this engine a number of others were built in which Newcomen himself was involved. They included collieries at Griff, Warwickshire (1711); Bilston, Staffordshire (1714); Hawarden, Flintshire (1715); Austhorpe, West Yorkshire (1715) and Whitehaven, Cumberland (1715).

Although many mine-owners used Newcomen's steam-engines, they constantly complained about the cost of using them. The main problem with it was they used a great deal of coal and were therefore expensive to run. While putting it back into working order, Watt attempted to discover how he could make the engine more efficient.

Watt later told his friend, the Glasgow engineer, Robert Hart: "I had gone to take a walk on a fine Sabbath afternoon. I passed the old washing-house. I was thinking upon the engine at the time and had gone as far as the Herd's house when the idea came into my mind, that as steam was an elastic body it would rush into a vacuum, and if a communication was made between the cylinder and an exhausted vessel, it would rush into it, and might be there condensed without cooling the cylinder."

Watt worked on the idea for several months and eventually produced a steam engine that cooled the used steam in a condenser separate from the main cylinder. Watt calculated that this would produce a saving of fuel of around 75 per cent. It has been argued by Jennifer Tann that "Watt identified several problems, of which the wastage of steam during the ascent of the engine piston and the method of vacuum formation in which the system was cooled were two of the most fundamental. He therefore made a new model, slightly larger than the original, and conducted many experiments on it.... The theory of latent heat underpinned Watt's experiments on the separate condenser, in which the steam cylinder remained hot while a separate condensing vessel was cold."

In April, 1765, James Watt wrote to James Lind about his invention. "I have now almost a certainty of the facturum of the fire-engine, having determined the following particulars: the quantity of steam produced; the ultimatum of the lever engine; the quantity of steam produced; the quantity of steam destroyed by the cold of its cylinder; the quantity destroyed in mine... mine ought to raise water to 44 feet with the same quantity of steam that there does to 32 (supposing my cylinder as thick as theirs). I can now make a cylinder of 2 feet diameter and 3 feet high only a 40th of an inch thick, and strong enough to resist the atmosphere... in short, I can think of nothing else but this machine."

James Watt built an instrument-maker's model but the next stage involved producing a massive working engine made of brick and iron. Watt had no money for large-scale models and so he had to seek a partner with capital. Watt's friend, Joseph Black, introduced him to John Roebuck, the owner of Carron Ironworks near Falkirk in Scotland. He also owned nearby coal mines to provide fuel for his ironworks.

Roebuck agreed and the two men went into partnership. Roebuck held two-thirds of the original patent (9th January 1769) in return for discharging some of Watt's debts. James Patrick Muirhead, the author of The Life of James Watt (1854) claims that Roebuck's made every effort to get Watt's machine into production as he was "ardent and sanguine in the pursuit of his undertakings".

In March 1773 Roebuck became bankrupt. At the time he owed Matthew Boulton over £1,200. Boulton knew about Watt's research and wrote to him making an offer for Roebuck's share in the steam-engine. Roebuck refused but on 17th May, he changed his mind and accepted Boulton's terms. James Watt was also owed money by Roebuck, but as he had done a deal with his friend, he wrote a formal discharge "because I think the thousand pounds he (Boulton) he has paid more than the value of the property of the two thirds of the inventions."

Roger Osborne, the author of Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution (2013) has argued: "The two men instantly knew they could work together. Perhaps Watt saw that Boulton was the necessary complement to his own gloomy character - an energetic optimist who would carry him through his difficulties - while Boulton surely recognised the seriousness of Watt's character.... Watt was delighted not just by the prospect of investment hut especially by Boulton's personal enthusiasm."

Boulton pointed out that before he would give Watt financial backing, he insisted that the 1769 patent, with only eight years to run, should be extended to twenty-five years. This meant petitioning the House of Commons. By 1775 the two men had their patent which gave them "the sole use and property of certain steam-engines of his invention, throughout the majesty's dominions." This prevented others from making steam-engines which contained improvements of their own.

Under the terms of the partnership Watt assigned two-thirds of both property and the patent to Boulton. In return Boulton undertook to pay the expenses already incurred, to meet the costs of experiments, and to pay for materials and wages. The profits were to be divided in proportion to their shares. "It would be incorrect to stereotype Boulton as the entrepreneur and Watt as the inventor, for Boulton made many suggestions for improvements to the engine and Watt also had a good head for business. But there is no doubt that Boulton's flair for marketing was significant for the early success of the business."

For the next eleven years Boulton's factory producing and selling Watt's steam-engines. These machines were mainly sold to colliery owners who used them to pump water from their mines. Watt's machine was very popular because it was four times more powerful than those that had been based on the Thomas Newcomen design.

One of their machines was installed at Whitbread's Brewery in London in 1775 to grind malt and raise the liquor, taking the place of a huge wheel which needed six horses at a time to turn it. The company was very pleased with the economic benefits of Watt's steam engine that had cost them £1,000.

Watt continued to experiment and in 1781 he produced a rotary-motion steam engine. Whereas his earlier machine, with its up-and-down pumping action, was ideal for draining mines, this new steam engine could be used to drive many different types of machinery. Richard Arkwright was quick to importance of this new invention, and in 1783 he began using Watt's steam-engine in his textile factories.

The ironmaster John Wilkinson, was one of the first people to buy Watt's steam engine. He installed eleven engines at his Bradley ironworks by the 1790s and at least seven elsewhere. The partners depended heavily on Wilkinson for it was he who was capable of boring engine cylinders with greater accuracy than any other iron-founder. His boring machine has been called the first machine tool that was developed in the industrial revolution.

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that James Watt's steam engine was "the foundation of industrial technology". Arthur Young commented in his book, Tours in England and Wales (1791) about the impact that Watt had on Britain: "What trains of thought, what a spirit of exertion, what a mass and power of effort have sprung in every path of life, from the works of such men as Brindley, Watt, Priestley, Harrison, Arkwright.... In what path of life can a man be found that will not animate his pursuit from seeing the steam-engine of Watt?"

Richard Guest pointed out that Watt's steam engine that drove the power looms was extremely popular with factory owners: "The increasing number of steam-looms is a certain proof of their superiority over the hand-looms. In 1818, there were in Manchester, Stockport, Middleton, Hyde, Stayley Bridge, and their vicinities, 14 factories, containing about 2,000 looms. In 1821, there were in the same neighbourhoods 32 factories, containing 5,732 looms. Since 1821, their number has still increased, and there are at present not less than 10,000 steam-looms at work in Great Britain."

Boulton & Watt company had a virtual monopoly over the production of steam-engines. Watt charged his customers a premium for using his steam engines. To justify this he compared his machine to a horse. Watt calculated that a horse exerted a pull of 180 lb., therefore, when he made a machine, he described its power in relation to a horse, i.e. "a 20 horse-power engine". Watt worked out how much each company saved by using his machine rather than a team of horses. The company then had to pay him one third of this figure every year, for the next twenty-five years.

Henry Brougham later recalled: "There was one quality, which most honourably distinguished him from too many inventors, and was worthy of all imitation, he was not only entirely free from jealously, but he exercised a careful and scrupulous self-denial, and was anxious not to appear, even by accident, as appropriating to himself that which he thought belonged to others."

James Watt became an important member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham. The group took this name because they used to meet to dine and converse on the night of the full moon. The group grew out of a friendship between Matthew Boulton and Erasmus Darwin and first began meeting as a group in 1768. Other members included Josiah Wedgwood, Joseph Priestley, James Brindley, Thomas Day, William Small, John Whitehurst, John Robison, Joseph Black, William Withering, John Wilkinson, Richard Lovell Edgeworth and Joseph Wright.

The historian, Jenny Uglow, has argued: "It has been said that the Lunar Society kick-started the industrial revolution. No individual or group can be said to change a society in such a way, and time and again one can see that if they hadn't invented or discovered something, someone else would have done it. Yet this small group of friends really was at the leading edge of almost every movement of its time in science, in industry and in the arts, even in agriculture. They were pioneers of the turnpikes and canals and of the new factory system. They were the group who brought efficient steam power to the nation."

Watt deeply felt the loss of some of his friends from the Lunar Society. A number of Watt's friends died at the turn of the century. Josiah Wedgwood (1795), Joseph Black (1799), Erasmus Darwin (1802), Joseph Priestley (1804) and John Robison (1805). It is claimed that in retirement he was haunted by the fear that his mental faculties were failing.

Watt's partner, Matthew Boulton, suffered from stones in the kidneys, and he told a friend: "My doctors say my only chance of continuing in this world depends on my living quiet in it." He died aged 81 of kidney failure on 17th August 1809. Watt wrote that Boulton was "not only an ingenious mechanic, well skilled in all the practices of the Birmingham manufacturers, but possessed in a high degree the faculty of rendering any new invention of his own or others useful to the public, by organising and arranging the processes by which it could be carried on."

James Watt died aged 73 at Heathfield in Handsworth, Birmingham, on 25th August 1819 and was buried beside Matthew Boulton in St Mary's Church on 2nd September 1819. He left over £60,000 (£81,000,000 in today's money) in his will to his family.

On this day in 1856 Margaret Ashton was born in Withington. She was the third of the six daughters and three sons of Thomas Ashton, a wealthy cotton manufacturer. Her father, was a Unitarian and an active member of the Liberal Party, and held progressive views on social reform.

In 1870 Ashton worked closely with Samuel Fielden, in raising money for Owens College, the Nonconformist education establishment founded in Manchester by the cotton-merchant, John Owens. By 1870 Fielden and Ashton had raised £200,000 for the college.

As her biographer, Peter D. Mohr, points out: "From 1875 Margaret Ashton worked on a voluntary basis as the manager of the Flowery Fields School in Hyde, which had been founded by her grandfather, for the children of mill workers. Her first involvement in politics came in 1888, when she helped to found the Manchester Women's Guardian Association, an organization which encouraged women to become poor-law guardians and to take a more active role in local politics."

Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999) claims that "her father refused her request to be taken into the family business, although she was able to concern herself with its welfare policy." In 1895 Margaret joined the Women's Liberal Federation, and the following year became a founder member of the Women's Trade Union League. She was also a member of the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies.

After the death of her father, Thomas Ashton, in 1898, Margaret became more active in politics and in 1900 she was elected to the Withington Urban District Council. Eight years later she became the first woman to the Manchester City Council. According to Peter D. Mohr: "As a councillor she devoted herself to the issues of women's health and education, and campaigned to improve the conditions of employment for women. She supported new legislation to improve the wages and conditions of factory girls, to raise the age of employment of children, and to abolish the sweated system."

In 1906 Margaret Ashton resigned from the Liberal Party when it became clear to her that Henry Campbell-Bannerman, decided that his government would not find time to allow legislation to be passed concerning women's suffrage. Ashton became chairperson of the North of England Society for Women's Suffrage, and financially supported its newspaper, The Common Cause.

Ashton remained committed to the use of constitutional methods to gain votes for women. Ashton, like other members of the NUWSS, feared that the militant actions of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) would alienate potential supporters of women's suffrage. However, Ashton admired the courage of the suffragettes and in 1906 she joined with Millicent Fawcett and Lilias Ashworth Hallett in organizing the banquet at the Savoy to celebrate the release from Holloway Prison of WSPU prisoners.

In July 1914 the NUWSS argued that Asquith's government should do everything possible to avoid a European war. Two days after the British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914, Millicent Fawcett declared that it was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Although the NUWSS supported the war effort, it did not follow the WSPU strategy of becoming involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces.

Despite pressure from members of the NUWSS, Fawcett refused to argue against the First World War. Her biographer, Ray Strachey, argued: "She stood like a rock in their path, opposing herself with all the great weight of her personal popularity and prestige to their use of the machinery and name of the union." At a Council meeting of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies held in February 1915, Fawcett attacked the peace efforts of people like Mary Sheepshanks. Fawcett argued that until the German armies had been driven out of France and Belgium: "I believe it is akin to treason to talk of peace."

After a stormy executive meeting in Buxton all the officers of the NUWSS (except the Treasurer) and ten members of the National Executive resigned over the decision not to support the Women's Peace Congress at the Hague. This included Ashton, Chrystal Macmillan, Kathleen Courtney, Catherine Marshall, Eleanor Rathbone and Maude Royden, the editor of the The Common Cause.

In April 1915, Aletta Jacobs, a suffragist in Holland, invited suffrage members all over the world to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Some of the women who attended included Mary Sheepshanks, Jane Addams, Alice Hamilton, Grace Abbott, Emily Bach, Lida Gustava Heymann, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse, Chrystal Macmillan, Rosika Schwimmer. At the conference the women formed the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WIL). Although the government blocked Ashton and other British women from travelling to the Hague, she immediately joined this organisation.

Margaret Ashton's pacifism made her unpopular during the First World War. Se was branded "pro-German" and ousted from Manchester City Council in 1921. Her civic work was never properly recognized; a portrait by Henry Lamb to commemorate her seventieth birthday was refused by the Manchester City Art Gallery as a protest against her pacifist views.

In later life she joined the National Council of Women, and helped to found the Manchester Women's Citizens Association. Mary Ashton died at her home, 12 Kingston Road, Didsbury, on 15th October 1937.

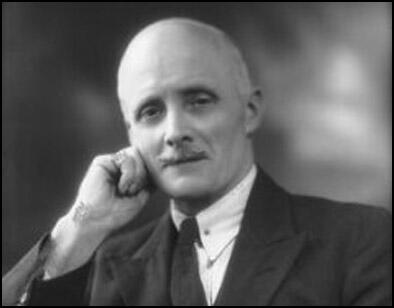

On this day in 1870 Arthur Pugh, the fifth child of William Pugh and his wife, Amelia Adlington Pugh, was born at Ross-on-Wye. Both his parents died when he was a child. He went to his local elementary school and at thirteen was apprenticed to a butcher. In 1894 he moved to Neath in Wales and found work in the steel industry.

After his marriage to Elizabeth Morris he became a smelter at the Frodingham Iron Works in Lincolnshire. He became active in the British Steel Smelters' Association (BSSA) and eventually became a branch secretary. In 1906 he became a full-time union official. Soon afterwards, John Hodge, was elected as the Labour Party MP for Gorton in Manchester. Pugh now replaced him as general secretary of the BSSA. Hamilton Fyfe, the editor of the Daily Herald, was never convinced by him as a committed trade unionist and that given different circumstances "he would have made a fortune as a chartered accountant".

In 1917 the BSSA became the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation. In 1920 Pugh was elected to the parliamentary committee of the Trade Union Congress, and six years later became its chairman. Later that year he replaced the left-winger Alonzo Swales as chairman of the TUC's Special Industrial Committee (SIC). This job became very important during the General Strike that began on 3rd May, 1926. The TUC adopted the following plan of action. To begin with they would bring out workers in the key industries - railwaymen, transport workers, dockers, printers, builders, iron and steel workers - a total of 3 million men (a fifth of the adult male population). Only later would other trade unionists, like the engineers and shipyard workers, be called out on strike. Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), was placed in charge of organising the strike.

John Hodge believed that Pugh was ambivalent about the dispute. "I have never heard him say that he was in favour of it, but I have never heard him say that he was against it." (5) Paul Davies, went further and claimed that Pugh was a reluctant participant in this conflict: "Pugh confessed that the SIC had no policy with which to conduct negotiations. The SIC reluctance to prepare was based on a complex mixture of moderation, defeatism and realism, but above all fear: fear of losing, fear of winning, fear of bloodshed, fear of unleashing forces that union leaders could not control." (6)

Walter Citrine, the general secretary of the TUC, was desperate to bring an end to the General Strike. He argued that it was important to reopen negotiations with the government. His view was "the logical thing is to make the best conditions while our members are solid". Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin refused to talk to the TUC while the General Strike persisted. Citrine therefore contacted Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), who shared this view of the strike, and asked him to arrange a meeting with Herbert Samuel, the Chairman of the Royal Commission on the Coal Industry.

Without telling the miners, the TUC negotiating committee met Samuel on 7th May and they worked out a set of proposals to end the General Strike. These included: (i) a National Wages Board with an independent chairman; (ii) a minimum wage for all colliery workers; (iii) workers displaced by pit closures to be given alternative employment; (iv) the wages subsidy to be renewed while negotiations continued. However, Samuel warned that subsequent negotiations would probably mean a reduction in wages. These terms were accepted by the TUC negotiating committee, but were rejected by the executive of the Miners' Federation.

Herbert Smith, the President of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB), was furious with the TUC for going behind the miners back. One of those involved in the negotiations, John Bromley of the NUR, commented: "By God, we are all in this now and I want to say to the miners, in a brotherly comradely spirit... this is not a miners' fight now. I am willing to fight right along with them and suffer as a consequence, but I am not going to be strangled by my friends." Smith replied: "I am going to speak as straight as Bromley. If he wants to get out of this fight, well I am not stopping him."

Walter Citrine wrote in his diary: "Miner after miner got up and, speaking with intensity of feeling, affirmed that the miners could not go back to work on a reduction in wages. Was all this sacrifice to be in vain?" Citrine quoted Cook as saying: "Gentleman, I know the sacrifice you have made. You do not want to bring the miners down. Gentlemen, don't do it. You want your recommendations to be a common policy with us, but that is a hard thing to do."

Smith asked Arthur Pugh if the decision was "the unanimous decision of your Committee?" Pugh replied that it was the view that the General Strike should come to an end. Smith pleaded for further negotiations. However, Pugh was insistent: "That is it. That is the final decision, and that is what you have to consider as far as you are concerned, and accept it."

On the 11th May, at a meeting of the Trade Union Congress General Committee, it was decided to accept the terms proposed by Herbert Samuel and to call off the General Strike. The following day, the TUC General Council visited 10 Downing Street and attempted to persuade the Government to support the Samuel proposals and to offer a guarantee that there would be no victimization of strikers.

Baldwin refused but did say if the miners returned to work on the current conditions he would provide a subsidy for six weeks and then there would be the pay cuts that the Mine Owners Association wanted to impose. He did say that he would legislate for the amalgamation of pits, introduce a welfare levy on profits and introduce a national wages board. The TUC negotiators agreed to this deal. As Lord Birkenhead, a member of the Government was to write later, the TUC's surrender was "so humiliating that some instinctive breeding made one unwilling even to look at them."

Baldwin already knew that the Mine Owners Association would not agree to the proposed legislation. They had already told Baldwin that he must not meddle in the coal industry. It would be "impossible to continue the conduct of the industry under private enterprise unless it is accorded the same freedom from political interference that is enjoyed by other industries."

To many trade unionists, Walter Citrine had betrayed the miners. A major factor in this was money. Strike pay was haemorrhaging union funds. Information had been leaked to the TUC leaders that there were cabinet plans originating with Winston Churchill to introduce two potentially devastating pieces of legislation. "The first would stop all trade union funds immediately. The second would outlaw sympathy strikes. These proposals would... make it impossible for the trade unions' own legally held and legally raised funds to be used for strike pay, a powerful weapon to drive trade unionists back to work."

Arthur Pugh and Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), informed the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) leaders, that if the General Strike was terminated the government would instruct the owners to withdraw their notices, allowing the miners to return to work on the "status quo" while the wage reductions and reorganisation machinery were negotiated. Arthur J. Cook, the general secretary of the MFGB, asked what guarantees the TUC had that the government would introduce the promised legislation, Thomas replied: "You may not trust my word, but will not accept the word of a British gentleman who has been Governor of Palestine".

When the General Strike was terminated, the miners were left to fight alone. On 21st June 1926, the British Government introduced a Bill into the House of Commons that suspended the miners' Seven Hours Act for five years - thus permitting a return to an 8 hour day for miners. In July the mine-owners announced new terms of employment for miners based on the 8 hour day. As Anne Perkins has pointed out this move "destroyed any notion of an impartial government".

Arthur J. Cook toured the coalfields making passionate speeches in order to keep the strike going: "I put my faith to the women of these coalfields. I cannot pay them too high a tribute. They are canvassing from door to door in the villages where some of the men had signed on. The police take the blacklegs to the pits, but the women bring them home. The women shame these men out of scabbing. The women of Notts and Derby have broken the coal owners. Every worker owes them a debt of fraternal gratitude."

Hardship forced men to begin to drift back to the mines. By the end of August, 80,000 miners were back, an estimated ten per cent of the workforce. 60,000 of those men were in two areas, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. "Cook set up a special headquarters there and rushed from meeting to meeting. He was like a beaver desperately trying to dam the flood. When he spoke, in, say, Hucknall, thousands of miners who had gone back to work would openly pledge to rejoin the strike. They would do so, perhaps for two or three days, and then, bowed down by shame and hunger, would drift back to work."

As one historian pointed out: "Many miners found they had no jobs to return to as many coal-owners used the eight-hour day to reduce their labour force while maintaining productions levels. Victimisation was practised widely. Militants were often purged from payrolls. Blacklists were drawn up and circulated among employers; many energetic trade unionists never worked in a it again after 1926. Following months of existence on meague lockout payments and charity, many miners' families were sucked by unemployment, short-term working, debts and low wages into abject poverty."

Pugh retired as secretary of the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation in 1937. He remained active in politics and helped to administer the Daily Herald. He also joined the British delegates on the economic consultative committee of the League of Nations. On the outbreak of the Second World War he served on the Central Appeal Tribunal under the Military Service Acts. In 1951 he published a history of the metal unions, Men of Steel. Arthur Pugh died on 2nd August 1955.

On this day in 1871 Frederick Maurice, the eldest son of Major-General John Frederick Maurice (1841–1912) and his wife, Anne Frances Fitzgerald, was born in Dublin on 19th January 1871. His grandfather was Frederick Denison Maurice, a leading Christian Socialist and the founder of the Working Men's College. His father was professor of military art and history at the Camberley Staff College.

Maurice was educated at St. Paul's School and the Sandhurst Royal Military College. He was commissioned in 1892 in the Derbyshire Regiment (Sherwood Foresters) and saw service in the Boer War. By 1899 he had reached the rank of major. After the war he graduated from the Staff College and served under General Douglas Haig in the directorate of staff duties at the War Office. In 1913 Maurice was appointed an instructor at the Staff College under General William Robertson. A strong friendship developed between the two men that was to last for the rest of their lives.

On the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 Maurice went to France as a staff officer with the 3rd division; he was soon promoted to head its general staff. He received praise for the way he dealt with the thirteen-day retreat from Mons to the Marne. In 1915 General Robertson became chief of staff to General John French, commander of the British Expeditionary Force. Soon afterwards Robertson selected Maurice to take charge of the operations section at general headquarters.

According to his biographer, Trevor Wilson: "They worked well together and Maurice was further promoted. Then in December Robertson was transferred to London to become chief of the Imperial General Staff and principal military adviser to the government. Maurice went with him, to become director of military operations at the War Office with the rank of major-general. At the War Office, Robertson and Maurice worked in agreement. They endorsed a strategy of concentrating Britain's military resources and operations on the western front against the armed might of Germany, and they resisted policies which would have directed Britain's endeavours towards lesser adversaries in more extraneous theatres."

General William Robertson became convinced that the war would be won on the Western Front. Robertson wrote on 8th February, 1915: "If the Germans are to be defeated they must be beaten by a process of slow attrition, by a slow and gradual advance on our part, each step being prepared by a predominant artillery fire and great expenditure of ammunition". His long-term friend, General Douglas Haig, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force, agreed with this strategy. He wrote in his autobiography, From Private to Field-Marshal (1926): "There was never, so far as I know, any material difference of opinion between us in regard to the main principles to be observed in order to win the war."

Robertson's biographer, David R. Woodward, has argued: "Assisted by his handpicked director of military operations, Sir Frederick B. Maurice, Robertson in his new role as chief of general staff attempted to solve the riddle of static trench warfare which had replaced the war of movement of the first months of the war. The ever-expanding system of earthworks had the property of an elastic band. They bent rather than broke. Robertson concluded that a decisive battle was unlikely so long as Germany had reserves to bring forward. To prevent the Germans from gradually giving ground while inflicting heavy losses on the attacker, Robertson and Maurice hoped to nail the defenders to their trenches by choosing an objective which the enemy considered strategically vital."

Herbert Henry Asquith, the prime minister, did not challenge this approach to the war. However, he lost office after the failure of the Somme Offensive on the Western Front. His replacement, David Lloyd George, disagreed with this strategy and at various stages advocated a campaign on the Italian front and sought to divert military resources to the Turkish theatre.

According to the historian, Michael Kettle, Maurice became involved in a plot to overthrow David Lloyd George. Others involved in the conspiracy included General William Robertson, Chief of Staff and the prime ministers main political adviser, Maurice Hankey, the secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID) and Colonel Charles Repington, the military correspondent of the Morning Post. Kettle argues that: "What Maurice had in mind was a small War Cabinet, dominated by Robertson, assisted by a brilliant British Ludendorff, and with a subservient Prime Minister. It is unclear who Maurice had in mind for this Ludendorff figure; but it is very clear that the intention was to get rid of Lloyd George - and quickly."

On 24th January, 1918, Repington wrote an article where he described what he called "the procrastination and cowardice of the Cabinet". Later that day Repington heard on good authority that Lloyd George had strongly urged the War Cabinet to imprison both him and his editor, Howell Arthur Gwynne. That evening Repington was invited to have dinner with Lord Chief Justice Charles Darling, where he received a polite judicial rebuke.

General William Robertson disagreed with Lloyd George's proposal to create an executive war board, chaired by Ferdinand Foch, with broad powers over allied reserves. Robertson expressed his opposition to General Herbert Plumer in a letter on 4th February, 1918: "It is impossible to have Chiefs of the General Staffs dealing with operations in all respects except reserves and to have people with no other responsibilities dealing with reserves and nothing else. In fact the decision is unsound, and neither do I see how it is to be worked either legally or constitutionally."

On 11th February, Charles Repington, revealed in the Morning Post details of the coming offensive on the Western Front. Lloyd George later recorded: "The conspirators decided to publish the war plans of the Allies for the coming German offensive. Repington's betrayal might and ought to have decided the war." Repington and his editor, Howell Arthur Gwynne, were fined £100 each, plus costs, for a breach of Defence of the Realm regulations when he disclosed secret information in the newspaper.

General William Robertson wrote to Repington suggesting that he had been the one who had leaked him the information: "Like yourself, I did what I thought was best in the general interests of the country. I feel that your sacrifice has been great and that you have a difficult time in front of you. But the great thing is to keep on a straight course". Maurice also sent a letter to Repington: "I have the greatest admiration for your courage and determination and am quite clear that you have been the victim of political persecution such as I did not think was possible in England."

Robertson put up a fight in the war cabinet against the proposed executive war board, but when it was clear that Lloyd George was unwilling to back down, he resigned his post. He was now replaced with General Henry Wilson. General Douglas Haig rejected the idea that Robertson should become one of his commanders in France and he was given the eastern command instead.

On 9th April, 1918, David Lloyd George, told the House of Commons that despite heavy casualties in 1917, the British Army in France was considerably stronger than it had been on January 1917. He also gave details of the number of British troops in Mesopotamia, Egypt and Palestine. Maurice, whose job it was to keep accurate statistics of British military strength, knew that Lloyd George had been guilty of misleading Parliament about the number of men in the British Army. Maurice believed that Lloyd George was deliberately holding back men from the Western Front in an attempt to undermine the position of Sir Douglas Haig.

Maurice wrote to Henry Wilson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff pointing out these inaccuracies. He did not receive a reply and after consulting with his wife and mother, he took the decision to write a letter to the newspapers giving the true figures. Maurice knew that by taking this decision, his military career would be brought to an end. However, as he said in a letter to his daughter Nancy: "I am persuaded that I am doing what is right, and once that is so, nothing else matters to a man. That is I believe Christ meant when he told us to forsake father and mother and children for his sake."

On 6th May, 1916, Maurice wrote a letter to the press stating that ministerial statements were false. The letter appeared on the following morning in the The Morning Post, The Times, The Daily Chronicle and The Daily News. The letter accused David Lloyd George of giving the House of Commons inaccurate information. The letter created a sensation. Maurice was immediately suspended from duty and supporters of Herbert Henry Asquith called for a debate on the issue.

Maurice's biographer, Trevor Wilson: "Despite containing some errors of detail, the charges contained in Maurice's letter were well founded. Haig had certainly been obliged against his wishes to take over from the French the area of front where his army suffered setback on 21 March. The numbers of infantrymen available to Haig were fewer, not greater, than a year before. And there were several more ‘white’ divisions stationed in Egypt and Palestine at the time of the German offensive than the government had claimed."

The debate took place on 9th May and the motion put forward amounted to a vote of censure. If the government lost the vote, David Lloyd George would have been forced to resign. As A.J.P. Taylor has pointed out: "Lloyd George developed an unexpectedly good case. With miraculous sleight of hand, he showed that the figures of manpower which Maurice impuhned, had been supplied from the war office by Maurice's department." Although many MPs suspected that Lloyd George had mislead Parliament, there was no desire to lose his dynamic leadership during this crucial stage of the war. The government won the vote with a clear majority.

Maurice, by writing the letter, had committed a grave breach of discipline. He was retired from the British Army and was refused a court martial or inquiry where he would have been able to show that David Lloyd George had mislead the House of Commons on both the 9th April and 7th May, 1918.

According to Trevor Wilson: "And although Lloyd George subsequently claimed that the government had been supplied with its figures concerning troop strengths on the western front by Maurice's own department (figures which happened to be inaccurate), these had only been provided after the statements by Lloyd George to which Maurice took exception, and had been corrected by the time Lloyd George made his rebuttal to Maurice in the parliamentary debate of 9 May. Whether, even so, a serving officer should have taken issue with his political masters in the public way Maurice did must remain a matter of opinion. Haig, for one, certainly thought not, as he recorded in his diary. Maurice himself took the view that, as a concerned citizen, he was obliged to rebut misleading statements by ministers which served to divert responsibility for setbacks on the battlefield from the political authorities, where it belonged, to the military. To this end he was prepared to sacrifice his career in the army."

After leaving the army Maurice became military correspondent of The Daily Chronicle. This was a surprising decision as Robert Donald, the editor, had been for a long time a close friend and loyal supporter of David Lloyd George. Donald had already rejected an offer of a knighthood from Lloyd George as he feared it might compromise his editorial freedom. It would seem that Donald was beginning to have doubts about the honesty of Lloyd George.

David Lloyd George was furious with Donald's decision to employ Maurice and on 5th October it was announced that a group of his friends led by Sir Henry Dalziel, had purchased the The Daily Chronicle. Both Robert Donald and Maurice were forced to resign from the paper.

After leaving the Daily Chronicle Maurice worked as the military correspondent of the Daily News, and later articles for the Westminster Gazette. He also wrote several books about the war including Intrigues of the War (1922), Governments and War (1926), British Strategy (1929) and The Armistices of 1918 (1943).

Edward Louis Spears, his future son-in-law, wrote: "As imperturbable as a fish, always unruffled, the sort of man who would eat porridge by gaslight on a foggy morning in winter… just as if he were eating a peach in a sunny garden in August. A very tall, very fair man, a little bent, with a boxer's flattened-out nose, and a rather abrupt manner. A little distrait owing to great inner concentration."

Frederick Maurice was also the principal of the Working Men's College (1922-1933) and East London College (1933-44). Highly valued as a lecturer, in 1926 he was also appointed professor of military studies at London University. He also taught for many years at Trinity College. He was also a leading figure in the British Legion. Frederick Maurice died at his home, 62 Grange Road, Cambridge on 19th May 1951.

On this day in 1887 Alexander Woollcott was born in Colts Neck Township, New Jersey, on 19th January, 1887. His father, Walter Woollcott, was a successful businessman and had an income of $5,700 but Woollcott later recalled that his memories of childhood are "slightly overcast by clouds of financial anxiety".

According to his biographer, Samuel Hopkins Adams, the author of Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (1946), Woollcott enjoyed a good relationship with his mother: "But for his father he conceived and maintained a dogged distaste. When the head of the family passed around the breakfast table, bestowing the morning kiss upon his offspring, Aleck would slyly thrust an upright fork above his ear in the fond hope of puncturing the paternal jowl. The dislike was not reciprocated. Walter Woollcott was carelessly interested in and amused by his youngest. He would recite classical passages to him and, while the boy was still very young, so thoroughly imbued him with the principles and strategy of cribbage and the game remained a source of permanent profit to Aleck."

One of his cousins claims that as a child he said he wanted to be a girl: "In his early teens he loved to dress up and pass himself off as a girl. Someone gave him a wig of beautiful brown hair, and he coaxed various bits of apparel from his sister, Julie, and her friends." At the age of fourteen he attended a New Year's party dressed as a girl and he began signing letters "Alecia".

Woollcott was unhappy at Central High School in Philadelphia. At an academic centenary he told the audience: "It is a tradition of the old alumnus, tottering back to the scene of his schooldays, to speak with great affection of the school. I must be an exception here tonight. During the four years that I attended Central High School I had a lousy time... I was something of an Ishmaelite among the students." However, he did have some inspirational teachers including Ernest Lacey, who wrote plays in verse and Franklin Spencer Edmonds, an imaginative and inspirational teacher of economics. Len Shippey, the author of Luckiest Man Alive (1959), claims that teacher Sophie Rosenberger "inspired him to literary effort" and with whom he "kept in touch all her life."

At the age of eighteen he entered Hamilton College in Clinton. One of the students, Merwyn Nellis, recalled: "Aleck, at the time, had a high-pitched voice, a slightly effeminate manner and an unusual - even eccentric - personality and appearance. He was far enough from the norm so that the first impression on a lot of healthy and immature boys was that he was a freak." Another student, Lloyd Paul Stryker, pointed out that he was unlike other young men at college in other ways as well: "We could not understand a freshman who had pondered, read, and thought so much."

Woollcott was an outstanding student and became editor of the Hamilton Literary Monthly . He also had stories published in various magazines. Albert A. Getman, another student at the college, claims that by his senior year he was "easily the most remarkable and accomplished person on the campus". He also added that he was also "the most unpopular" student at Hamilton. One of the reasons for this was his cruel wit. One student commented that "he could squash with a compliment as well as with a smashing blow." Samuel Hopkins Adams has argued: "He thought of himself as a Socialist, without any real comprehension of what it meant. To the end his political and economic thinking, coloured by emotion and prejudice, was, notwithstanding his sincerity, superficial and unclear."

After graduating he applied to Carr Van Anda, the managing director of the New York Times, for a job. One of his first assignments was to investigate the killing of a policeman, Edgar Rice, in Coatesville, Pennsylvania. While he was in the town Zachariah Walker, a "feeble-minded negro" was arrested. "Five hundred steel workers stormed the hospital where the negro lay with a police bullet in his body, took him out, and roasted him to death over a slow fire while two thousand onlookers cheered." According to Walter Davenport, who was working for the Philadelphia Public Ledger, Woollcott went to see the mayor of the town: "Mr. Shallcross, I represent The New York Times, which must insist that you take immediate measures to fetch the perpetrators of this wholly unnecessary outrage to book or justice or whatever your quaint custom may be here in Coatesville". When Woollcott's article of the lynching was published in the newspaper, Richard Harding Davis, telephoned the editor and commented: "They don't do newspaper writing any better than that."

During this time he met the young writer, Walter Duranty. They spent a lot of time together and later Woollcott commented about Duranty: "No other man... could make a purposeless hour at the sidewalk cafe so memorably delightful." They visited nightclubs and theatres together and it was Woollcott who first gave Duranty the idea that he should take up journalism. Another friend during this period was Cornelius Vanderbilt III, who described him as "a plump, good-natured cuss, rather showy and gaudy, who liked to hang around late and talk."

Soon after joining the newspaper he was diagnosed as suffering from mumps. According to the author of Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (1946): "In great pain he dosed himself with Julie's morphine for a fortnight, when the swelling began to subside. But the damage was done. Thereafter he was, if not totally neutralized, permanently depleted of sexual capacity. Another sequel was the unhealthy fat of semi-eunuchism." However, this did not stop him falling in love with Jane Grant, a young reporter at the New York Times.

In 1914 Woollcott became the drama critic of the New York Times. He had strong opinions on how the job should be done. "There is a popular notion that a dramatic criticism, to be worthy of the name, must be an article of at least 1,000 words, mostly polysyllables and all devoted - perfectly devoted - to the grave discussion of some play as written and performed... The tradition of prolixity and the dullness in all such writing is as old as Aristotle and as lasting as William Archer." His daily column was an instant success. One journalist argued: "Woollcott set forth reflectively his opinions of plays and players against a background of broad dramatic knowledge, spicing the seriousness of his treatment with lively anecdotal matter. No one else had done the same thing as well."

In the winter of 1914 Woollcott joined Walter Duranty, who was now also working for the New York Times and Wythe Williams in Paris. During this period Duranty described Woollcott as "an exhilarating companion of my youth". They together covered the trial of Henriette Caillaux, who had murdered Gaston Calmette, the editor of Le Figaro, who she had accused of slandering her husband, Joseph Caillaux, the Minister of Finance.

When President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany and entered the First World War, Woollcott offered his services to the US Army. His biographer, Samuel Hopkins Adams, has pointed out: "Only his physique stood between him and military glory. He was fat, flabby, and myopic. But beneath that inauspicious exterior burned a crusading flame. Some way or another he could be of service: some way or another he was bound to get in. No combat unit would look at him twice."

Eventually he was accepted by the medical service. He was sent to Saint-Nazaire and worked at Base Hospital No. 8. Sally J. Taylor has pointed out: "Pudgy and artistically inclined, the New York Times drama critic didn't seem cut out for the vicissitudes of soldiering, but immediately after the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, there he was, lining up to share in all of the rights and privileges extended to a private in the U.S. Army. He hoped, he explained somewhat shamefacedly to his friends, that basic training would run some of the fat off him, and it must have done so because he good-humoredly made it through the ordeal and thus across the Atlantic, making light of any inconvenience or embarrassment he had suffered.... Not surprisingly, he was immensely popular, not only with the string of celebrities who found their way into the orderly room at the hospital but also with his patients and fellow workers. Somehow, he always managed to have a bottle of something drinkable on hand for anything that could be construed as an appropriate occasion."

The author of Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (1946): "He (Alexander Woollcott) was the least military figure in the A.E.F. His uniform, soiled, sagging, and corrugated with unexpected bulges, looked as if it had just emerged from the delousing plant. His carriage was grotesque. He had the air of submitting to drill in a spirit of tolerance rather than from any recognition of authority or respect for discipline. He hated M.P.s and resented shoulder-strap superiority. To be sure, he possessed certain compensating virtues, but they were not of the obviously soldierly kind. He had courage, hardihood, endurance, self-reliance, enterprise, a burning enthusiasm for the service, and an unflagging willingness to do more than his share. Useful as these qualities may be in the field, they do not commend themselves to brass-hattery as do a straight back and a snappy salute. Sergeant Woollcott would hardly have won a commission had the war lasted twenty years."

After being promoted to the rank of sergeant he was assigned to the recently established Stars and Stripes, a weekly newspaper by enlisted men for enlisted men. Harold Ross was appointed editor. Aware of his great journalistic talent, Ross sent him to report on the men in the front-line trenches. It was claimed he "made his way fearlessly in and around the front, gathering material for the kinds of things the fighting men wanted to read: stories about rotten cooks, nosey dogs, leaky boots, and other common nuisances of life at the front." Albian A. Wallgren, provided a cartoon of Woollcott the accompany his articles. The figure of a "chubby soldier in uniform and a raincoat, his gas mask worn correctly across his chest, and a small musette bag at his side, tin hat placed correctly, straight across his head, puttees rolled beautifully, prancing with that almost effeminate rolling gait of Aleck's."

One of his colleagues claimed he showed great bravery in reporting life on the Western Front. "The road ahead of us was being shelled and the chauffeur could see this plainly and to our intense alarm. Woollcott said nothing about it, however, and neither did the chauffeur or I, figuring (as we realized on subsequent comparing of emotions) that we'd be damned if we said anything about stopping until he did. we got into Thiacourt all right, and got out of it all right. We walked out because, after we got in, an officer sent our car back, it being conspicuous and things being too hot. He asked why the hell we'd taken a chance on driving into the place and Aleck explained that he hadn't seen any shelling." As a friend pointed out, Woollcott had chosen not to see the shelling: "Aleck may have had imperfect vision, but his hearing was unimpaired... and an approaching and exploding shell makes quite a noticeable commotion."

Heywood Broun, in one of his articles, quotes William Slavens McNutt, who also reported on the First World War with Woollcott. "All hell had broken loose in a valley just below us and I was taking cover in a ditch as Aleck and Arthur Ruhl (Collier's Weekly war correspondent) ambled briskly past me on their way into action. Aleck had a frying pan strapped around his waist, and an old grey shawl across his shoulders. Whenever it was necessary to duck from a burst of shellfire, Aleck would place the shawl carefully in the middle of the road and sit on it."

Woollcott arranged for Jane Grant to become a singer with the YMCA Entertainment Corps in France. Samuel Hopkins Adams points out: "Presently he was talking marriage. It was mostly in a tone of banter, but at times he became earnest and seemed to be trying to persuade himself as well as the girl that they might make a go of it, for a time, anyway - and how about taking a chance? Not being certain how far he meant it, and, in any case, not being interested, she laughed it off. Some of his friends thought that she treated the whole affair in a spirit of levity and that Aleck was cruelly hurt." Jane later married Harold Ross.

On his return to New York City Woollcott published a couple of articles based on his experiences on the Western Front. These two articles were added to a selection of his articles from Stars and Stripes and published as The Command Is Forward: Tales of the A.E.F. Battlefields (1919). The book received very little attention from the critics. He told one friend that he returned to the New York Times in "a sort of fog of the soul."

Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley all worked at Vanity Fair during the First World War. They began taking lunch together in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel. Sherwood was six feet eight inches tall and Benchley was around six feet tall, Parker, who was five feet four inches, once commented that when she, Sherwood and Benchley walked down the street together, they looked like "a walking pipe organ." John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971) has argued that Woollcott "resembled a plump owl... who was a droll, often preposterous, often sentimental, often waspish, and always flamboyantly self-dramatic."

"John Peter Toohey, a theater publicist, and Murdock Pemberton, a press agent, decided to throw a mock "welcome home from the war" celebration for the egotistical, sharp-tongued columnist Alexander Woollcott. The idea was really for theater journalists to roast Woollcott in revenge for his continual self-promotion and his refusal to boost the careers of potential rising stars on Broadway. On the designated day, the Algonquin dining room was festooned with banners. On each table was a program which misspelled Woollcott's name and poked fun at the fact that he and fellow writers Franklin Pierce Adams (F.P.A.) and Harold Ross had sat out the war in Paris as staff members of the army's weekly newspaper, the Stars and Stripes, which Bob had read in the trenches. But it is difficult to embarrass someone who thinks well of himself, and Woollcott beamed at all the attention he received. The guests enjoyed themselves so much that John Toohey suggested they meet again, and so the custom was born that a group of regulars would lunch together every day at the Algonquin Hotel."

Murdock Pemberton later recalled that he owner of the hotel, Frank Case, did what he could to encourage this gathering: "From then on we met there nearly every day, sitting in the south-west corner of the room. If more than four or six came, tables could be slid along to take care of the newcomers. we sat in that corner for a good many months... Frank Case, always astute, moved us over to a round table in the middle of the room and supplied free hors d'oeuvre... The table grew mainly because we then had common interests. We were all of the theatre or allied trades." Case admitted that he moved them to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, so others could watch them enjoy each other's company.

The people who attended these lunches included Woollcott, Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Donald Ogden Stewart, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Franklin Pierce Adams, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Frank Crowninshield, Ben Hecht, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire. This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table.

Samuel Hopkins Adams, the author of Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (1946), has argued: "The Algonquin profited mightily by the literary atmosphere, and Frank Case evinced his gratitude by fitting out a workroom where Broun could hammer out his copy and Benchley could change into the dinner coat which he ceremonially wore to all openings. Woollcott and Franklin Pierce Adams enjoyed transient rights to these quarters. Later Case set aside a poker room for the whole membership." The poker players included Woollcott, Herbert Bayard Swope, Harpo Marx, Jerome Kern and Prince Antoine Bibesco. On one occasion, Woollcott lost four thousand dollars in an evening, and protested: "My doctor says it's bad for my nerves to lose so much." It was also claimed that Harpo Marx "won thirty thousand dollars between dinner and dawn".

Edna Ferber wrote about her membership of the group in her book, A Peculiar Treasure (1939): "The contention was that this gifted group engaged in a log-rolling; that they gave one another good notices, praise-filled reviews and the like. I can't imagine how any belief so erroneous ever was born. Far from boosting one another they actually were merciless if they disapproved. I never have encountered a more hard-bitten crew. But if they liked what you had done they did say so, publicly and wholeheartedly. Their standards were high, their vocabulary fluent, fresh, astringent and very, very tough. Theirs was a tonic influence, one on the other, and all on the world of American letters. The people they could not and would not stand were the bores, hypocrites, sentimentalists, and the socially pretentious. They were ruthless towards charlatans, towards the pompous and the mentally and artistically dishonest. Casual, incisive, they had a terrible integrity about their work and a boundless ambition."

Woollcott published a couple of articles based on his experiences on the Western Front. These two articles were added to a selection of his articles from Stars and Stripes and published as The Command Is Forward: Tales of the A.E.F. Battlefields (1919). The book received very little attention from the critics. He told one friend that he returned to the New York Times in "a sort of fog of the soul."

In 1922 Woollcott published Shouts and Murmurs: Echoes of a Thousand and One First Nights: "It might be pointed out that the review of a play as it appears in the morning newspapers is addressed not to the actors nor to the playwrights, but to the potential playgoer, that the dramatic critic's function is somewhat akin to that of the attendant at some Florentine court whose uneasy business was to taste each dish before it was fed to anyone that mattered. He is an ink stained wretch, invited to each new play and expected, in the little hour that is left him after the fall of the curtain, to transmit something of that play's flavour, to write, with whatever of fond tribute, sharp invective, or amiable badinage will best express it, a description of the play as performed, in terms of the impression it made upon himself."

Woollcott remained a member of the Algonquin Round Table. They played games while they were at the hotel. One of the most popular was "I can give you a sentence". This involved each member taking a multi syllabic word and turning it into a pun within ten seconds. Dorothy Parker was the best at this game. For "horticulture" she came up with, "You can lead a whore to culture, but you can't make her thin." Another contribution was "The penis is mightier than the sword." They also played other guessing games such as "Murder" and "Twenty Questions". Woollcott called Parker "a combination of Little Nell and Lady Macbeth."

Woollcott was strongly attracted to the artist Neysa McMein. However, one of his friends suggested he "just wants somebody to talk to in bed." Samuel Hopkins Adams, the author of Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (1946) disagreed with this view and argued that Woollcott was very serious about her: "Neysa McMein was a reigning toast of the Algonquin Sophisticates and the object of unrequited passion to several... Woollcott, now cured of his disappointment over Jane Grant, had joined the court of Miss McMein's devotees, where the others never saw any occasion to be jealous of him."

Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987), has written in some detail about his relationship with McMein: "Alec constituted Neysa's longest and most constant 'extramarital' relationship... However, because of his stunted sexuality, there was often an unconsummated quality about Alec's quasi-sexual relationships, never more so than in the case of Neysa, who was the most overtly sensuous of all the women to whom he was close. Throughout their relationship the two often played at a coy sexual game based on, or at least allowed by, Alec's near eunuchhood.... Often Neysa was Alec's companion for opening nights. The tall, beautiful Neysa, usually dressed oddly or eccentrically, and the obese, plain Alec, in his dandified cloak and hat, made for a queer-looking couple. It is very doubtful that on such occasions Alec solicited Neysa's theatrical opinions - or that he even gave her sufficient chance to voice them, for Alec's great forte was monologue, not repartee, and Neysa was, apart from his large radio audience, among the most admiring and indulgent of his listeners. From time to time, but less frequently than with some other of his good and true friends, Alec would become overbearing and there would have to be, at Neysa's insistence, a trial separation of some weeks or months."

Jack Baragwanath , the husband of Neysa McMein, later recalled in his autobiography, A Good Time was Had (1962): that he never liked Woollcott: " Among all of Neysa's friends there was only one man I disliked: Alexander Woollcott. Unfortunately, he was one of Neysa's closest and oldest attachments and seemed to regard her as his personal property. I knew, too, that she was deeply fond of him, which made my problem much harder, for I imagined the consequences of the sort of open row which Alec often seemed bent on promoting. When he and I were alone he was disarmingly pleasant, but in a group he would sometimes go out of his way to make me feel small. I was no match for him at the kind of thrust and parry that was his forte, but after a while I found that if I could make him mad, he would drop his rapier and furiously attack with a heavy mace of anger, with which he would sometimes clumsily knock himself over the head. Then I would have him.... Close as Neysa and Alec were, and as much as he loved her, his uncontrollable tongue would get the better of him and he would say something so cruel and spiteful to her that she would refuse to see him for as long as six months at a time. And there were little incidents, not infrequent ones, when he would obviously try to hurt her."

Woollcott considered Alice Duer Miller to be along with Dorothy Parker to be the cleverest of the women who were members of the Algonquin Round Table. According to Samuel Hopkins Adams, the author of Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (1946), "Miller's character and mentality he considered far above her product as a novelist, while not belitting the agreeable quality of her fiction." Alice pointed out in a discussion on quarrels with Woollcott on the radio that they held very different opinions on the subject: "You advocating them as a means of clearing up inherent disagreements between friends, I disapproving of them on the ground that nothing worth quarrelling about could ever really be forgiven." Alice once said, when clearly thinking of Woollcott: "If it's very painful for you to criticize your friends - you're safe in doing it. But if you take the slightest pleasure in it, that's the time to hold your tongue."

Some members of the Algonquin Round Table began to complain about the nastiness of some of the humour as it gained the reputation for being the "Vicious Circle". Donald Ogden Stewart commented: "It wasn't much fun to go there, with everybody on stage. Everybody was waiting his chance to say the bright remark so that it would be in Franklin Pierce Adams' column the next day... it wasn't friendly... Woollcott, for instance, did some awfully nice things for me. There was a terrible sentimental streak in Alec, but at the same time, there was a streak of hate that was malicious."

John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1975) has argued that Woollcott was mainly responsible for this change in atmosphere: "Over the years, good humour had given way to banter, and now banter had given way to insult. If any one person could be considered instrumental in having brought this change about, that would have been Alexander Woollcott, whose sense of humour was undependable. On one occasion it led him to advise a young lady that her brains were made of popcorn soaked in urine... Woollcott was a perplexing man, given to many kindnesses and generosities, but at the same time he seemed to feel a need to find the minutest chinks in his friends' armour, wherein to insert a poisoned needle."