Edward Burrough

Edward Burrough, son of James Burrough a farmer, was born at Underbarrow, near Kendal, on 1 March 1633. Nothing is known of his mother, except that she died in 1658, or of his other siblings. (1)

The family had conventional religious views and according to Burrough the family would together say prayers, read the Bible and listen to sermons, and sing hymns. (2) A friend stated, that he had "honest parents who had a good report among their neighbours for their upright and honest dealing". (3)

Burrough was extremely religious as between the ages of twelve and sixteen, Burrough began travelling throughout Westmorland to hear presbyterian speakers. However he did not find what he was looking for and this gave him a strong feeling of isolation. Burrough consequently became an object of ridicule, "some of my former acquaintance began to scorn me, calling me a Roundhead". (4)

Edward Burrough - Quaker

In 1652 he heard the preaching of George Fox, a young man who had been travelling the country for the last ten years. According to Pauline Gregg he had came to the simple realization that the spirit of God was within each man, and that the knowledge of Christ was an inner light that could reveal itself at any time without the help of dogma, form, or ceremony. "A man need be equipped with nothing but a humble spirit and a belief in God and Jesus Christ. No prayer-book, no preacher, no sacrament, no church, who needed to guide him - only the witness in his conscience." (5)

Fox refused to bow or to take off his hat to anyone, to use the pronouns "Thee" and "Thou" to all men and women whether they were rich or poor, never to call the days of the week or the months of the year by their names but only by their numbers. He would enter church services and denounce the preacher in the midst of his sermon. Fox attempted to teach the conviction of moral perfection and "almost a personal infallibility, of spirit-inspired utterance". (6) In one pamphlet Fox stated: "Did not the Whore of Rome give you the name of vicars... and parsons and curates?" (7)

During this period Fox called his followers "Children of the Light", "People of God", "Royal Seed of God" or "Friends of the Truth". However, one of his critics, Gervase Bennett, described Fox and his followers as Quakers. This was a derisive term and was based on the fact that Fox's followers quaked and trembled during their worship. Fox defended his followers by pointing out that there were numerous biblical figures who were said to have also trembled before the Lord. Later they became known as the "Religious Society of Friends". (8)

Burrough became a Quaker. His parents disowned him and the relationship never recovered and on their deaths in 1658, he observed "the old man and old woman... according to the flesh, is both departed." (9) By this time he was one of movement's leading preachers. He toured the country with his friend Francis Howgill, but the two men were especially important in London. One of the men who the couple converted in 1654 described them as "the Apostles of this City in their Day" (10)

James Nayler

Another important Quaker preacher was James Nayler who was the leading figure in the movement in London. Nayler was an accomplished speaker and writer, as well as a creative thinker. William Dewsbury, who had the opportunity to watch both Fox and Nayler when they visited Northampton, marveled at the way Nayler "confounded the deceit" of the audience and thought he was a greater speaker than Fox. (11)

Christopher Hill has argued that many people in the movement regarded Nayler as the "chief leader" and the "head Quaker in England". (12) Colonel Thomas Cooper pointed out in the House of Commons: "He (Nayler) writes all their books. Cut off this fellow and you will destroy the sect." (13) Even one of his critics, John Deacon, conceded that he was "a man of exceeding quick wit and sharp apprehension, enriched with that commendable gift of good oratory with a very delightful melody in his utterance." (14)

No written rules governed the Society of Friends because it was a kind of community of equals, all committed to the same goals and having the interests of the group at heart. The question of leadership was left open. Fox and Nayler had been involved in the movement together almost from the beginning and shared many days and nights of travelling, and co-authored pamphlets and epistles. However, by 1655 Fox came infrequently to London, preferring to continue his travels in the countryside, and some regarded Nayler as the movement's leader. This was especially true of Martha Simmonds, "an intelligent and independent person, author of several moving pamphlets about spiritual seeking and apocalyptic hopes." (15)

Fox became concerned about how Nayler was winning such a fervent band of disciples in London. It seemed to Fox that Nayler was erecting a base of influence that gave him a strength and a prestige independent of Fox. In the meetings he held he began talking about "wicked mountains and parties crying against him". With the ability to win followers, "Nayler posed a threat of major proportions to Fox. No movement can follow two masters, as Fox realized." (16)

Burrough and Howgill spent the winter of 1655–6 in Ireland, making friends of people such as John Perrot. When they returned to London they found the dispute between Fox and Nayler was harming the movement. Howgill went as far as saying that their main enemy was "within". Both Burrough and Howgill were involved in the disciplining of James Nayler and his followers. (17)

In October 1656, Nayler re-enacted the Palm Sunday arrival of Christ in Jerusalem. Seated on an ass he was escorted into Bristol by women strewing branches in his path. Oliver Cromwell and other members of the House of Commons were horrified by Nayler allowing himself to be hailed by devoted disciples as a new Messiah. Nayler was arrested. Philip Skippon, a staunch presbyterian and the major-general in charge of the London area, complained that Cromwell's policy of toleration had fostered a Quaker threat: "Their great growth and increase is too notorious, both in England and Ireland; their principles strike at both ministry and magistracy. Many opinions are in this nation (all contrary to the government) which would join in one to destroy you, if it should please God to deliver the sword into their hands." (18)

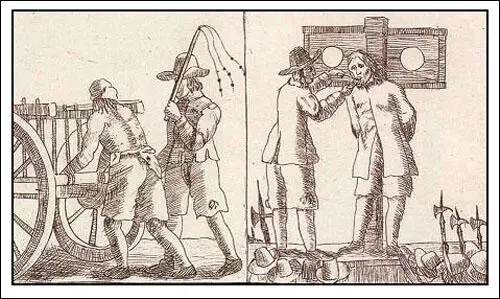

At his trial before Parliament, Nayler declared that he had enacted a "sign" without mistaking himself for Christ. A few members were prepared to accept his account, but the majority were determined on punishment and disagreed only as to its extent. By the narrow margin of 96 to 82, a motion to put him to death was defeated, and after further debate it was resolved on 16 December that Nayler be whipped through the streets by the hangman, exposed in the pillory, have his tongue bored through with a red-hot iron, and have the letter B (for blasphemy) branded on his forehead. He was then to be returned to Bristol and compelled to repeat his ride in reverse while facing the rear of his horse, and finally he was to be committed to solitary confinement in Bridewell Prison for an indefinite period. (19)

Nayler's punishment was carried out in every detail, including 300 lashes that tore all the skin off his back, and the concluding scene at the pillory was witnessed by a large crowd that included Thomas Burton, the MP for Westmorland. He approved of the punishment but admired Nayler's stoicism: "He put out his tongue very willingly, but shrinked a little when the iron came upon his forehead. He was pale when he came out of the pillory, but high-coloured after tongue-boring… Nayler embraced his executioner, and behaved himself very handsomely and patiently." (20)

George Fox refused to sign a petition asking that Nayler's punishment be remitted. Fox also endorsed Parliament's actions against Nayler: "If the seed of the serpent speaks and says he is Christ that is the liar and the blasphemy and the ground of all blasphemy." It has been pointed out that Nayler had been convicted for something that Fox had done, claimed to be the "Son of God".Alexander Parker argued that by alienating the Naylerites, Fox was weakening the movement. Robert Rich, a successful merchant and shipowner from London, was criticised by Fox for his support and continued public defense of the jailed Quaker. (21)

Fox believed that Nayler had been attracting the following of the Ranters. This was supported by Thomas Collier who wrote in 1657 that "any that know the principles of the Ranters" may easily recognize that Quaker doctrines are identical. Both would have "no Christ but within; no Scripture to be a rule; no ordinances, no law but their lusts, no heaven nor glory but here, no sin but what men fancied to be so, no condemnation for sin but in the consciences of ignorant ones". Only Quakers "smooth it over with an outward austere carriage before men, but within are full of filthiness". (22)

Edward Burrough, who had earlier been associated with the Ranters distanced himself from the movement that its leading figures, Abiezer Coppe and Laurence Clarkson advocated "free love". (23) Coppe asserted that property was theft and pride worse than adultery: "I can kiss and hug ladies and love my neighbour's wife as myself without sin." (24) Peter Ackroyd claimed that Coppe and Clarkson professed that "sin had its conception only in imagination" and told their followers that they "might swear, drink, smoke and have sex with impunity". (25) One slogan used by the Ranters included: "There's no heaven but women, nor no hell save marriage." (26) Burrough claimed that the Ranters "have scorned self-righteousness"; their house had once been the house of prayer, though now it has become "the den of robbers", cultivating false peace, false liberty and love and fleshly joy. (27)

Fox's conflict with Nayler highlighted the disruptive side to the individualistic faith of the Quakers. Fox realised he would need to find a way to impose discipline. On the question of individualism versus authority, Fox came down on the side of authority. "A two-level system was erected, a meeting at a local level, a larger and more distant one a rung higher, forming a systematic check on a potential dissident's outward expression of inward leadings as determined by those gripping the instruments of power." (28)

Restoration

In 1658 Edward Burrough was imprisoned in Kingston upon Thames for his refusal to swear the oath of abjuration. His unwillingness to pay his fine of £100 meant he spent seven months in prison. (29) Burrough's main contribution to Quakerism was a series of pamphlets that attacked people who he considered "ungodly" such as John Bunyan and Richard Baxter. Burrough's religious certainty also made him critical of Oliver Cromwell. In A Message to the Present Rulers of England (1659) he told the army's leaders that if they continued in their treachery, God would judge them. (30)

In 1658 Oliver Cromwell announced that he wanted his son, Richard Cromwell, to replace him as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. The English army was unhappy with this decision. While they respected Oliver as a skillful military commander, Richard was just a country farmer. To help him Cromwell brought him onto the Council to familiarize him with affairs of state. (31)

Oliver Cromwell died on 3rd September 1658. Richard Cromwell became Lord Protector but he was bullied by conservative MPs into support measures to restrict religious toleration and the army's freedom to indulge in political activity. The army responded by forcing Richard to dissolve Parliament on 21st April, 1659. The following month he agreed to retire from government. (32)

Parliament and the leaders of the army now began arguing amongst themselves about how England should be ruled. General George Monk, the officer in charge of the English army based in Scotland, decided to take action, and in 1660 he marched his army to London. According to Hyman Fagan: "Faced with a threatened revolt, the upper classes decided to restore the monarchy which, they thought, would bring stability to the country. The army again intervened in politics, but this time it opposed the Commonwealth". (33)

Monck reinstated the House of Lords and the Parliament of 1640. Royalists were now in control of Parliament. Monck now contacted Charles, who was living in Holland. Charles agreed that if he was made king he would pardon all members of the parliamentary army and would continue with the Commonwealth's policy of religious toleration. Charles also accepted that he would share power with Parliament and would not rule as an 'absolute' monarch as his father had tried to do in the 1630s. (34)

Despite this agreement a special court was appointed and in October 1660 those Regicides who were still alive and living in Britain were brought to trial. Ten were found guilty and were sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. This included Thomas Harrison, John Jones, John Carew and Hugh Peters. Others executed included Adrian Scroope, Thomas Scot, Gregory Clement, Francis Hacker, Daniel Axtel and John Cook. On the way to his execution, Harrison said: "I go to suffer upon the account of the most glorious cause that ever was in the world." (35)

Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton, Thomas Pride and John Bradshaw were all posthumously tried for high treason. They were found guilty and on the twelfth anniversary of the regicide, on 30th January 1661, their bodies were disinterred and hung from the gallows at Tyburn. (36) Cromwell's body was put into a lime-pit below the gallows and the head, impaled on a spike, was exposed at the south end of Westminster Hall for nearly twenty years. (37)

The Restoration divided Quakers into two groups: those who found reassurance in Fox's message to trust in God and the inevitable workings of God's will, and those who expected the Society of Friends to take a more militant stance. Edward Burrough was one of those who sought confrontation with the authorities. Burrough was arrested on 1 June 1661. He refused to back down and he died aged twenty-nine in Newgate prison on 14 February 1663. (38)

Primary Sources

(1) Edward Burrough, The case of free liberty of conscience in the exercise of faith and religion presented unto the King and both Houses of Parliament (1661)

Forasmuch as it hath pleased the Lord God of Heaven and Earth, (who is mighty and powerful, and bringeth to pass whatsoever he will in the Kingdomes of this World, so to suffer it to be accomplished, that power and authority is given unto you, to exercise over these Kingdomes; And whereas the people of these Nations (over whom your Authority is extended) are divided in their Judgments in matters Spiritual, and are of different Principles and ways in Relation to Faith and Worship and practises of Religion, and yet are all of them free-born people, and Natives of these Kingdoms, and as such ought to possesse and injoy their Lives, Liberties and Estates by the just Lawes of God and man; And may not justly any of them be destroyed by you, nor one sort of another, in their Persons and Estates, by Death, Banishment or other Persecutions, for and because only of their differences in matters of opinion and judgement, nor though they are contrary minded in profession of Faith and Worship and Religion, while they do walk peaceably and justly in their Conversations, under the Kings Authority, and do not make practise of their Religion, to the violating of the Government, nor to the injury of other mens Persons or Estates, but ought rather to be defended and Protected by you in all their rights both as men and Christians, both in things Civil and Spiritual, Notwithstanding their difference in matters Religious as aforesaid, they giving proof of their peaceable and honest deportment towards the King and his Government, and the people of these Kingdomes.

And therefore that due care may be had, as justly it ought to be by you, for the Peace and Prosperity and happiness of these Kingdomes, and that the just Liberties both civil and Spiritual of all people therein, may be allowed and maintained in all the Kings Dominions, and that unity and peace may be fully established, and justice and Righteousness only brought forth in the Land, and all Persecution, Hatred, Contention and Rebellion may die and perish and never more appear; And that all Christian people (though different in judgement and practises in matters of Faith and worship) may be protected to live a quiet and peaceable life in all Godliness and honesty under this Government, and that indignation and vengeance may he diverted from these Lands, which seems to threaten because of the contrary, and that blessings and peace may come, and rest upon this people forever.

Therefore for these ends and causes, and in the Name of the Lord I do propound unto you, and lay before you on the behalf of all the divided people of these Kingdoms, That free Liberty of Conscience in the exercise of Faith, Worship and Religion to God-wards, may be allowed and maintained unto all, without any imposition, violence or persecution exercised about the same, on the persons, Estates, or consciences of any in any relation of Religion, the Worship of God, Church Government and Ministry; But that all Christian People may be left free in all these Kingdomes, in the exercise of Conscience without being restrained from, or compelled to any way of Worship and practise of Religon, upon any pains and penalties, and that every one may be admitted to worship God in that way as his spirit perswades the heart, and may be defended in such their profession of Religion, while they make not use of their Liberty to the detrement of any other mens persons or Estates as aforesaid.

And let it not seem strange to you, why I appear in this manner and matter, at such a season as this; for your very happiness, prosperity and establishment, or the contrary, dependeth hereupon, even in allowing and maintaining liberty of Conscience in the exercise of Religion, or in limiting and forcing and persecuting about the same, and this may appear if ye justly consider these things following.

The Lordship in and over conscience, and the exercise thereof in all matters of Faith, and worship and duty to Godwards, is Gods alone only and proper right and priviledge, and he hath reserved this power and Authority in himself, and not committed the Lordship over Conscience, nor the exercise thereof, in the cases of faith and worship, to any upon Earth, not to prescribe and impose principles and Practises of Faith and worship and Religion, by force and violence on the persons and Consciences of men, but this belongs only to God, even to work faith in the heart, and to convert to holiness, and to lead and teach people by his Spirit in his worship, and to exercise their Consciences in all his wayes; For the Apostles themselves said, they had not Dominion over the Faith of the Saints, 2 Cor. 1. 24. but the Lord alone. And King Charles the first, said in his Meditations, I have often declared how little I desire my Laws and Scepter should intrench on Gods Soveraignity which is the only King of mens Consciences, etc So that to be Lord in Conscience and exerciser thereof in all the matters of Gods King|dome, is his only proper right, and to him alone it appertains.

And therefore consider if ye do not allow free liberty of Conscience, and give unto God the Lordship and exercise thereof in all matters of Faith and Worship to him-wards, but do impose by violence in forcing to, and restraining from such and such wayes of Religion, then ye take Dominion over mens faith, which ye ought not to do, and ye intrench on Gods Soveraignity, and usurps his Authority in exercising Lordship over the Conscience, in and over which Christ is only King as before recited, and ye ought not to take his right from him, nor to exercise that Authority over mens faith and Conciences which only appertains unto him, as his proper priviledge; for in so doing how dangerous effects may it bring forth, even ye may easilie provoke the Lord to wrath against you, and bring upon your selves sorrow and misery, if ye excise violence upon mens Consciences in and concerning Religious matters, contrary to the Scriptures and the example of Primitive Christians who were persecuted for their Conscience sake, but did never persecute nor punish any for that cause, nor ever used violence about their Religion, as Charles the I in his meditations nothing (said he) violent nor injurious can be religious.