Thomas Newcomen

Thomas Newcomen, was one of two sons of Elias Newcomen, a freeholder, shipowner, and merchant, and his wife, Sarah. He was born in Dartmouth, and baptized at St Saviour's Church on 28th February 1664. His mother died when he was 3 years-old, and he was brought up by Elias Newcomen's new wife, Alice Trenhale. (1)

Newcomen served an engineering apprenticeship in Exeter before he commenced trading as an ironmonger in about 1685. Over the next few years, with his partner, John Calley (1663–1717), he made equipment for the mines of Devon and Cornwall which produced tin and copper. (2) According to John Theophilus Desaguliers both men were Anabaptists. (3)

One of the major problems of mining for coal, iron, lead and tin in the 17th and 18th centuries was flooding. Miners used several different methods to solve this problem. These included pumps worked by windmills and teams of men and animals carrying endless buckets of water. In 1698 Thomas Savery developed a machine to pump water out of the mines. However, the engine could not raise water from very deep mines. Another disadvantage was its tendency to cause explosions. (4)

Newcomen worked on this problem and he eventually came up with the idea of a machine that would rely on atmospheric air pressure to work the pumps, a system which would be safe, if rather slow. The "steam entered a cylinder and raised a piston; a jet of water cooled the cylinder, and the steam condensed, causing the piston to fall, and thereby lift water." (5)

As Jenny Uglow has pointed out: "Newcomen's engines exploited basic atmospheric pressure, building on the way had been found to rush into a vacuum. A vacuum could be created by sucking air out of a closed vessel with a pump, but it could also be created by using steam." (6)

John Theophilus Desaguliers was someone who took a close interest in the development of this machine. "About the year 1710 Thomas Newcomen, Ironmonger and John Calley, glazier, of Dartmouth… anabaptists, made then several experiments in private, and having brought (their engine) to work with a piston... In the latter end of the year 1711 made proposals to draw the water at Griff, in Warwickshire; but their invention meeting not with reception... after a great many laborious attempts, they did make the engine work; but not being either philosophers to understand the reason, or mathematicians enough to calculate the powers and to proportion the parts, very luckily by accident found what they sought for." (7)

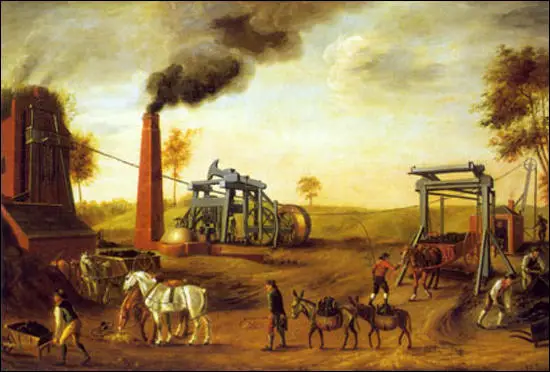

The engine was set up next to the mine it was draining. It had a large, rocking overhead beam. From one end hung a chain which was attached to the top of a piston encased in a cylinder. According to Gavin Weightman, the author of The Industrial Revolutionaries (2007), Newcomen and Calley had "devised and brought to efficient working order was the first really reliable steam engine in the world". (8)

Following the undoubted success of this engine a number of others were built in which Newcomen himself was involved. They included collieries at Griff, Warwickshire (1711); Bilston, Staffordshire (1714); Hawarden, Flintshire (1715); Austhorpe, West Yorkshire (1715) and Whitehaven, Cumberland (1715). During 1715 Newcomen's partner, John Calley became ill and died. (9)

In 1716 Newcomen was granted a patent for his steam-driven pumping engine. The London Gazette reported: "Whereas the invention for raising water by the impellant force of fire, authorized by Parliament, is lately brought to the greatest perfection, and all sorts of mines, etc., may be thereby drained and water raised to any height with more ease and less charge than by the other methods hitherto used, as is sufficiently demonstrated by diverse engines of this invention now at work in the several counties of Stafford, Warwick, Cornwall, and Flint. These are therefore, to give notice that if any person shall be desirous to treat with the proprietors for such engines, attendance will be given for that purpose every Wednesday at the Sword Blade Coffee House in Birchin Lane, London." (10)

Over the next few years over 100 of these machines were purchased. This included several machines sold overseas. He continued to improve the machine. In early models the steam in the cylinder was cooled by running cold water over the outside. Later it was discovered that an injection of cold water into the cylinder was much more effective. (11) He continued to work on developing other machines. In 1725 he wrote to the Lord Chief Justice Robert Raymond about "a new invented wind engine". (12)

It seems that Newcomen was well-respected by fellow businessmen who seemed very pleased with the performance of his machine. In 1719 James Lowther wrote to John Spedding: "There is nothing that will do our business so well and be less liable to accidents than the engine, and… it s the cheapest, safest and best way of keeping the colliery dry." (13) In another letter Lowther wrote: "Mr. Newcomen is a perfect honest man and had helped to make this matter easy, he owns none of the rest that had Fire Engines have been so fair with them as we have." (14)

Thomas Newcomen died in London on 5th August 1729. He was buried in the nonconformist burial-ground at Bunhill Fields, Finsbury.

Primary Sources

(1) John Theophilus Desaguliers, Experimental Philosophy (1744)

About the year 1710 Thomas Newcomen, Ironmonger and John Calley, glazier, of Dartmouth… anabaptists, made then several experiments in private, and having brought (their engine) to work with a piston... In the latter end of the year 1711 made proposals to draw the water at Griff, in Warwickshire; but their invention meeting not with reception, in March following, through the acquaintance of Mr. Potter of Bromsgrove, in Worcestershire, they bargained to draw water for Mr. Back of Wolverhampton where, after a great many laborious attempts, they did make the engine work; but not being either philosophers to understand the reason, or mathematicians enough to calculate the powers and to proportion the parts, very luckily by accident found what they sought for.

(2) The London Gazette (14th August 1716)

Whereas the invention for raising water by the impellant force of fire, authorized by Parliament, is lately brought to the greatest perfection, and all sorts of mines, etc., may be thereby drained and water raised to any height with more ease and less charge than by the other methods hitherto used, as is sufficiently demonstrated by diverse engines of this invention now at work in the several counties of Stafford, Warwick, Cornwall, and Flint. These are therefore, to give notice that if any person shall be desirous to treat with the proprietors for such engines, attendance will be given for that purpose every Wednesday at the Sword Blade Coffee House in Birchin Lane, London.

(3) Gavin Weightman, The Industrial Revolutionaries (2007)

Thomas Newcomen, after more than a decade of experimentation with his engineer colleague John Calley, devised a new kind of steam-driven pumping engine: he was obliged to go into partnership with Savery. This was hard on Newcomen but no more distressing than the bitter disputes that were to attend the development of the steam engine over the next century. The issue was not so much piracy by foreigners as infighting among the rival inventors and their champions.Thomas Newcomen was descended from a distinguished English family which, over several generations, had fallen on hard times. He was a skilled craftsman making equipment for the mines of Devon and Cornwall which produced tin and copper. As with coal mines, the exhaustion of seams near the surface forced the miners to dig deeper wherever they could.They quickly found that mines of any depth were unworkable unless water was pumped out of them continuously. A variety of horse-driven, windmill or manual pumps were used but they were limited in the amount of water they could raise. Keeping and feeding `gin' horses was also extremely expensive.

Savery had the right idea but the wrong machine for mines. His pumps could only draw water from a limited depth, while his partial use of high pressure steam was potentially hazardous. Newcomen and Galley came up with the answer: they would rely on atmospheric air pressure to work their pumps, a system which would be safe, if rather slow What they devised and brought to efficient working order was the first really reliable steam engine in the world. It did not matter that it was a leviathan of a structure with its great pivoted beam see-sawing back and forth alarmingly. There was no question of this engine going anywhere: it was stationary and set up in a brick shell of a building next to the mine it was draining.

The big, rocking overhead beam was the key to the whole thing. From one end hung a chain which was attached to the top of a kind of crude piston encased in a cylinder. A coal-fired boiler generated steam which was fed into the cylinder, filling it and driving out most of the air. The steam in the cylinder was then cooled. In the early models this was done by running cold water over the outside. Later it was discovered that an injection of cold water into the cylinder was much more effective.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)