On this day on 14th March

On this day in 1764 Charles Grey was born at Fallodon. His father, General Charles Grey, was one of Britain most important military commanders. He was later granted the titles Viscount Howick and Earl Grey. After being educated at Winchester and King's College, Cambridge, Charles Grey toured Europe.

At the age of twenty-two Charles Grey he became the Member of Parliament for Northumberland. Although his father was a staunch Tory, Grey soon became a follower of Charles Fox, the leader of the Radical Whigs in the House of Commons. Like Fox, Grey disliked William Pitt and was a consistent critic of the British Prime Minister.

Grey did not agree with those who advocated universal suffrage but he did feel that there was a strong need to improve the parliamentary system in Britain. In April 1792, Grey joined with a group of pro-reform Whigs to form the Friends of the People. Three peers (Lord Porchester, Lord Lauderdale and Lord Buchan) and twenty-eight Whig MPs joined the group. Other leading members included Richard Sheridan, Major John Cartwright, Lord John Russell, George Tierney,Thomas Erskine and Samuel Whitbread. The main objective of the the society was to obtain "a more equal representation of the people in Parliament" and "to secure to the people a more frequent exercise of their right of electing their representatives". Charles Fox was opposed to the formation of this group as he feared it would lead to a split the Whig Party.

On 30th April 1792, Charles Grey introduced a petition in favour of constitutional reform. He argued that the reform of the parliamentary system would remove public complaints and "restore the tranquillity of the nation". He also stressed that the Friends of the People would not become involved in any activities that would "promote public disturbances". Although Charles Fox had refused to join the Friends of the People, in the debate that followed, he supported Grey's proposals. When the vote was taken, Grey's proposals were defeated by 256 to 91 votes.

On 6th May 1793, Charles Grey once again introduced a parliamentary reform bill. Grey argued that one of the basic principles established by the Glorious Revolution of 1688 was the freedom of elections to the House of Commons. Grey added that "a man ought not to be governed by laws, in the framing of which he had not a voice, either in person or by his representative, and that he ought not to be made to pay any tax to which he should not have consented in the same way." Grey also attacked William Pitt, the Prime Minister, for the way that he exploited the present system. Grey pointed out that Pitt had created 30 new peers who nominated or indirectly influenced the return of a total of 40 MPs.

Charles Fox and Richard Sheridan supported Grey in the debate that followed. Robert Jenkinson and Lord Mornington, spoke against. So also did William Pitt who argued that any reform at this time would give encouragement to the Radicals in Britain who were supporting the French Revolution. When the vote was taken, Grey's proposals were defeated by 282 to 41. Members of the Friends of the People now realised they had no chance of persuading the House of Commons to accept parliamentary reform and the group disbanded.

In 1794 Charles Grey spoke against the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act and the following year he opposed the Seditious Meetings Bill. Frustrated by Pitt's refusal to consider parliamentary reform, Charles Grey decided to stop attending debates at the House of Commons. After a three year absence Grey returned in 1800 to oppose the Act of Union with Ireland.

In April 1803 Henry Addington offered Grey a place in his coalition government he refused with the comment that he would not take office without Charles Fox. When Fox entered the cabinet in January 1806, Grey joined him as first Lord of the Admiralty.

After the death of Charles Fox on 13th September, 1806, Charles Grey became leader of the Whig section of the government. Grey now became Foreign Secretary and leader of the House of Commons and was responsible for the act abolishing the African Slave Trade. In March 1807 George III ordered Lord Grenville's government not to introduce any more controversial measures. Grenville's government believed this instruction was unconstitutional and they resigned.

Charles Grey's father died on 16th November 1807. He now inherited his father's title and moved to the House of Lords. Although he was no longer in the House of Commons Earl Grey continued to play an active role in politics. He took part in the campaign for Catholic Emancipation and changes in the parliamentary system but was unsuccessful in persuading Lord Liverpool and his Tory government to introduce reforms. Grey opposed the renewal of war with France in 1815 and denounced the Gagging Acts imposed in 1817.

In June 1830 Earl Grey made an impressive speech on the need for parliamentary reform. The Duke of Wellington, the prime minister and leader of the Tories in Parliament, replied that the "existing system of representation was as near perfection as possible". It was now clear that the Tories would be unwilling to change the electoral system and that if people wanted reform they had to give their support to the Whigs.

On 15th November, 1830 Wellington's government was defeated in a vote in the House of Commons. The new king, William IV, was more sympathetic to reform than his predecessor and decided to ask Earl Grey to form a government. As soon as Grey became prime minister he formed a cabinet committee to produce a plan for parliamentary reform. Details of the proposals were announced on 3rd February 1831. The bill was passed by the House of Commons by a majority of 136, but despite a powerful speech by Earl Grey, the bill was defeated in the House of Lords by forty-one.

The defeat of the Reform Act resulted in Earl Grey calling a general election. The Whigs were popular with the electorate and after the election they had a larger majority than before in the House of Commons. A second reform bill was also defeated in the House of Lords. When people heard the news, riots took place in several British towns. Nottingham Castle was burnt down and in Bristol the Mansion House was set on fire.

In 1832 Earl Grey tried again but the House of Lords refused to pass the bill. Grey now appealed to William IV for help. He agreed to Grey's request to create a large number of new Whig peers. When the Lords heard the news, they agreed to pass the Reform Act. On 7th June the Bill received the Royal Assent and large crowds celebrated in the streets of Britain.

Earl Grey now called another general election and in the new reformed House of Commons, Grey had a majority of over a hundred. The Whigs were now able to introduce and pass a series of reforming measures. This included an act for the abolition of slavery in the colonies and the 1833 Factory Act. After the passing of the 1834 Poor Law Earl Grey decided to resign from office.

Earl Charles Grey died on 17th July, 1845.

On this day in 1848 George Reynolds spoke at a large Chartist meeting that took place at Kennington Common. at the National Convention he represented Derby. At the assembly Reynolds called for the Chartists to establish their own parliament in opposition to the House of Commons. However, he was a strong opponent of Fergus O'Connor and Physical Force Chartism.

Reynolds started his own radical journal, Reynolds Political Instructor and for a short period had a circulation of 30,000 a week. When he closed the journal he replaced it with the Reynolds's Weekly Newspaper. The first edition was published on Sunday, 5th May, 1850 and he kept it going for the rest of his life. George Reynolds died on 17th June 1879.

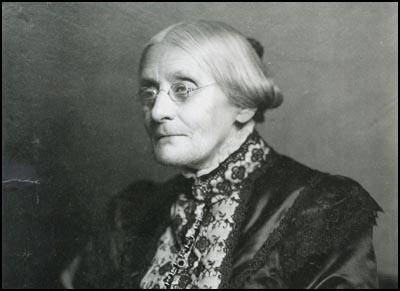

On this day in 1906 Susan B. Anthony died. Susan Brownell Anthony, the daughter of Daniel Anthony, a cotton manufacturer, was born in Adams, Massachusetts, on 15th February, 1820. Her father was a Quaker who campaigned against the slave trade.

After an education at her father's school and a Philadelphia boarding school, she began teaching at a female academy near Rochester, New York.

In 1852 Anthony joined with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Amelia Bloomer in campaigning for women's suffrage and equal pay. Anthony also became involved in the campaign for prohibition and was active in the American Anti-Slavery Society and helped escaped slaves on the Underground Railroad.

During the American Civil War Anthony strongly supported the Union cause. She also aided the administration of President Abraham Lincoln by forming the Women's Loyal League. In 1866 Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott and Lucy Stone established the American Equal Rights Association. The following year, the organisation became active in Kansas where Negro suffrage and women's suffrage was to be decided by popular vote. However, both ideas were rejected at the polls. In 1868 Anthony and Stanton founded the political weekly, The Revolution.

In 1869 Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton formed a new organisation, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). The organisation condemned the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments as blatant injustices to women. The NWSA also advocated easier divorce and an end to discrimination in employment and pay. Anthony toured the country making speeches on women's rights. In one year alone, she travelled 13,000 miles and made over 170 speeches. In 1872 Anthony attempted to vote in a an election in Rochester. She was arrested, charged and later found guilty of violating voting rights.

Another group, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), was also active in the campaign for women's rights and by the 1880s it became clear that it was not a good idea to have two rival groups campaigning for votes for women. After several years of negotiations, the AWSA and the NWSA merged in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Elizabeth Cady Stanton became the NAWSA's first president, but Anthony took over in 1892 and held the post for the next eight years.

Susan B. Anthony was also a historian and with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, she complied and published the four volume, The History of Woman Suffrage (1881-1902).

On this day in 1912 Charlotte Marsh is arrested for taking part in a window-smashing campaign in London. It is claimed that she alone smashed nine windows in the Strand during this demonstration. Emily Blathwayt wrote in her diary: "Linley had a nice letter from C. A. L. Marsh in Holloway awaiting her trial as they all refused bail. His birthday letter to her begging her not to take part in violence followed her there. Like the rest, they all think it their duty to take a large share of suffering." As she had previous convictions she was sentenced to six months' in Aylesbury Prison. She took part in the hunger-strike and was forcibly fed.

Charlotte Marsh, the daughter of Arthur Hardwick Marsh (1842-1909), an artist, was born in 1887. She was educated at St Margaret's School, Newcastle upon Tyne, and Roseneath, Wrexham, and then spent a year studying in Bordeaux.

Marsh joined the Women Social & Political Union in March 1907 but did not become an active member until she finished her training as a sanitary inspector a year later. According to her biographer, Michelle Myall: "She was one of the first women to train as a sanitary inspector but, appalled by the insight her work gave her into the lives of many women, gave up a promising career to join the women's suffrage movement in 1908, to give women a voice in public affairs." On 30th June 1908 she was arrested with Elsie Howey and charged with obstructing the police. She was found guilty and sentenced to a month's imprisonment in Holloway Prison.

A wealthy supporter of the WSPU donated money to buy Emmeline Pankhurst a motor car so that she could travel the country in comfort. According to Martin Pugh, the author of The Pankhursts (2001), Marsh applied for the job of driving the car. However, Vera Holme, got the post, but there were occasions when she worked as Pankhurst's chauffeur.

On 22nd September 1909 Charlotte Marsh was arrested along with Rona Robinson, Laura Ainsworth and Mary Leigh while disrupting a public meeting being held by Herbert Asquith. As Michelle Myall has pointed out: "The police attempted to move the two women by, among other methods, turning a hosepipe on them and throwing stones. However, Charlotte Marsh and Mary Leigh proved to be formidable opponents and were only brought down from the roof when three policeman dragged them down."

On 22nd September 1909 she was arrested along with Rona Robinson, Laura Ainsworth and Mary Leigh while disrupting a public meeting being held by Herbert Asquith. As Michelle Myall has pointed out: "The police attempted to move the two women by, among other methods, turning a hosepipe on them and throwing stones. However, Charlotte Marsh and Mary Leigh proved to be formidable opponents and were only brought down from the roof when three policeman dragged them down."

Marsh, Robinson, Ainsworth and Leigh were all sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment. They immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the three women by force.

C.P. Scott wrote to Asquith complaining of the "substantial injustice of punishing a girl like Miss Marsh with two months hard labour plus forcible feeding." According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "The Prison Visiting Committee reported that at first she had to be fed by placing food in the mouth and holding the nostrils, but that she later took food from a feeding cup." Votes for Women, on her release, reported that she had been fed by tube 139 times. Although her father was seriously ill, the authorities refused to release Marsh early. Marsh left Winson Green Prison on 9th December, 1909. She immediately dashed to her family home in Newcastle upon Tyne but he was already unconscious and he died a few days later.

In February 1910 Charlotte Marsh was WSPU organiser in Oxford. She then moved onto Portsmouth and in September 1910 she ran a WSPU holiday campaign in Southsea. During this period a fellow suffragette described her as "a tall young woman, of quiet, resolute bearing." The Times reported that she was "strikingly beautiful with blue eyes and long corn-coloured hair." Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence described her as one of the "saints of the Church Militant".

Marsh visited Eagle House near Batheaston in April 1911 with Annie Kenney and Laura Ainsworth. Their host, was Mary Blathwayt, a fellow member of the WSPU. Her father Colonel Linley Blathwayt planted a tree, a Picea Polita, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. Mary's mother, Emily Blathwayt, commented in her diary: "Miss Marsh planted her tree. She greatly dislikes her first name Charlotte and all her friends call her Charlie. Her label will be C. A. L. Marsh. (She also goes by the name of Calm). We liked very much what we saw of her. She is very fair with light hair and a pretty face. She is very tall ... She has a wonderful constitution and seems very well after all she has gone through. She has begun the late custom of not taking meat or chicken. She seems a very nice quiet girl."

In 1912 she became WSPU organiser in Nottingham. She also spent time in London working alongside Grace Roe. In June 1913 she was the Standard Bearer at the funeral of Emily Wilding Davison.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

Charlotte Marsh initially accepted this policy and worked as a motor mechanic before becoming the chauffeur of David Lloyd George "accepting his suggestion that the relationship would promote the victory of the cause of women's enfranchisement". She also worked as a member of the Women's Land Army in Surrey.

Marsh became increasingly critical of the way that Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst were running the WSPU during the First World War. Questions were also being asked about the funds of the WSPU. According to Martin Pugh, the author of The Pankhursts (2001): "The accounts had not been rendered since February 1914 when an annual income of £46,000 had been recorded. Moreover, the conviction that this money had been misappropriated for the Pankhursts' own purposes continued to rankle for many years." In March 1916, Charlotte Marsh set up the Independent WSPU.

After the war Marsh worked for Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. According to Elizabeth Crawford: "She then spent some time with the Department of Social Work in San Francisco and then with the Overseas Settlement League. By 1934 she was working with the Public Assistance Department of the London County Council." Marsh was also, along with Margaret Haig Thomas and Theresa Garnett, an executive member of the Six Point Group. She was also vice-president of the Suffragette Fellowship.

Charlotte Marsh, who never married, died at her home, 31 Copse Hill, Wimbledon, on 21st April 1961.

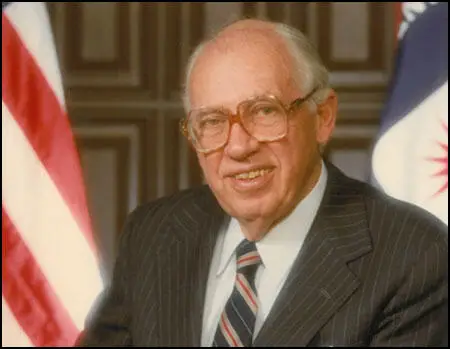

On this day in 1913 CIA director William J. Casey was born in New York. He graduated from Fordham University in 1934. Later he studied law at St. John's University. After law school, he joined the Research Institute of America, rising to become chairman of the institute's board of editors.

During the Second World War Casey served in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Sent to France he received the Bronze Star for his work in coordinating French Resistance forces in support of the D-Day invasion of Normandy. In 1945 he took over from Paul Helliwell, as head of the Secret Intelligence Branch of the OSS in Europe.

After the war he served as associate general counsel at the European headquarters of the Marshall Plan. He returned to the United States in 1949 where he practiced law and engaged in various publishing and entrepreneurial activities in New York City.

In 1971 he became chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission. He also served as Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs and president and chairman of the Import-Export Bank of the United States.

A member of the Republican Party, he directed the presidential campaign of Ronald Reagan in 1980. During the campaign Casey was informed that Jimmy Carter was attempting to negotiate a deal with Iran to get the American hostages released. This was disastrous news for the Reagan campaign. If Carter got the hostages out before the election, the public perception of the man might change and he might be elected for a second-term.

According to Barbara Honegger, a researcher and policy analyst with the 1980 Reagan/Bush campaign, William Casey and other representatives of the Reagan presidential campaign made a deal at two sets of meetings in July and August at the Ritz Hotel in Madrid with Iranians to delay the release of Americans held hostage in Iran until after the November 1980 presidential elections. Reagan’s aides promised that they would get a better deal if they waited until Carter was defeated.

On 22nd September, 1980, Iraq invaded Iran. The Iranian government was now in desperate need of spare parts and equipment for its armed forces. Jimmy Carter now proposed that the US would be willing to hand over supplies in return for the hostages.

Once again, the Central Intelligence Agency leaked this information to Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. This attempted deal was also passed to the media. On 11th October, the Washington Post reported rumors of a “secret deal that would see the hostages released in exchange for the American made military spare parts Iran needs to continue its fight against Iraq”.

A couple of days before the election Barry Goldwater was reported as saying that he had information that “two air force C-5 transports were being loaded with spare parts for Iran”. This was not true. However, this publicity had made it impossible for Carter to do a deal. Ronald Reagan on the other hand, had promised the Iranian government that he would arrange for them to get all the arms they needed in exchange for the hostages. According to Mansur Rafizadeh, the former U.S. station chief of SAVAK, the Iranian secret police, CIA agents had persuaded Khomeini not to release the American hostages until Reagan was sworn in. In fact, they were released twenty minutes after his inaugural address.

Reagan appointed William J. Casey as director of the Central Intelligence Agency. In this position he was able to arrange the delivery of arms to Iran. These were delivered via Israel. By the end of 1982 all Regan’s promises to Iran had been made. With the deal completed, Iran was free to resort to acts of terrorism against the United States. In 1983, Iranian-backed terrorists blew up 241 marines in the CIA Middle-East headquarters.

The Iranians once again began taking American hostages in exchange for arms shipments. On 16th March, 1984, William Francis Buckley, a diplomat attached to the U.S. Embassy in Beirut was kidnapped by the Hezbollah, a fundamentalist Shiite group with strong links to the Ruhollah Khomeini regime. Buckley was tortured and it was soon discovered that he was the CIA station chief in Beirut.

Buckley had also worked closely with William Casey in the secret negotiations with the Iranians in 1980. Buckley had a lot to tell his captors. He eventually signed a 400 page statement detailing his activities in the CIA. He was also videotaped making this confession. Casey asked Ted Shackley for help in obtaining Buckley’s freedom.

Three weeks after Buckley’s disappearance, President Ronald Reagan signed the National Security Decision Directive 138. This directive was drafted by Oliver North and outlined plans on how to get the American hostages released from Iran and to “neutralize” terrorist threats from countries such as Nicaragua. This new secret counter terrorist task force was to be headed by Shackley’s old friend, General Richard Secord. This was the beginning of the Iran-Contra deal.

Talks had already started about exchanging American hostages for arms. On 30th August, 1985, Israel shipped 100 TOW missiles to Iran. On 14th September they received another 408 missiles from Israel. The Israelis made a profit of $3 million on the deal.

In October, 1985, Congress agreed to vote 27 million dollars in non-lethal aid for the Contras in Nicaragua. However, members of the Ronald Reagan administration decided to use this money to provide weapons to the Contras and the Mujahideen in Afghanistan.

The following month, Ted Shackley traveled to Hamburg where he met General Manucher Hashemi, the former head of SAVAK’s counterintelligence division at the Atlantic Hotel. Also at the meeting on 22nd November was Manucher Ghorbanifar. According to the report of this meeting that Shackley sent to the CIA, Ghorbanifar had “fantastic” contacts with Iran. At the meeting Shackley told Hashemi and Ghorbanifar that the United States was willing to discuss arms shipments in exchange for the four Americans kidnapped in Lebanon. The problem with the proposed deal was that William Francis Buckley was already dead (he had died of a heart-attack while being tortured).

Ted Shackley recruited some of the former members of his CIA Secret Team to help him with these arm deals. This included Thomas Clines, Raphael Quintero, Ricardo Chavez and Edwin Wilson of API Distributors. Also involved was Carl E. Jenkins and Gene Wheaton of National Air. The plan was to use National Air to transport these weapons.

In May 1986 Gene Wheaton told Casey about what he knew about this illegal operation. Casey refused to take any action, claiming that the agency or the government were not involved in what later became known as Irangate.

Wheaton now took his story to Daniel Sheehan, a left-wing lawyer. Wheaton also contacted Newt Royce and Mike Acoca, two journalists based in Washington. The first article on this scandal appeared in the San Francisco Examiner on 27th July, 1986. As a result of this story, Congressman Dante Facell wrote a letter to the Secretary of Defense, Casper Weinberger, asking him if it "true that foreign money, kickback money on programs, was being used to fund foreign covert operations." Two months later, Weinberger denied that the government knew about this illegal operation.

Charles E. Allen, a national intelligence officer for counter-terrorism, went to see Robert Gates on 1st October, 1986, and told him that he believed that the proceeds from the Iran arms sales may have been diverted to support the contras. Gates then passed this information onto Casey.

On 5th October a Sandinista patrol in Nicaragua shot down a C-123K cargo plane that was supplying the Contras. Eugene Hasenfus, an Air America veteran, survived the crash and told his captors that he thought the CIA was behind the operation. Two days later, Roy M. Furmark, who was working for Adnan Khashoggi, told Casey that his boss was owed $10 million for his role played in the arms-hostages deal. Furmark also claimed that the man behind the deal was Oliver North.

On 9th October, Casey and Robert Gates had lunch with Oliver North. It seems that the CIA wanted to see the paperwork for the delivery of arms to Iran. Gates told North: "If you think it's that sensitive we can put it in the director's personal safe. But we need our copy." That afternoon, Casey appeared before two Congressional oversight committees, where he maintained that the CIA had nothing to do with the supplying of contras.

On 15th October, leaflets were given out in Tehran stating that high-ranking advisers to President Ronald Reagan had been visiting Iran the previous month to negotiate a deal to release hostages for arms. Two days later, Charles E. Allen provided Casey with a seven-page assessment of the "arms-hostage machinations". Allen wrote: "The government of the United States, along with the government of Israel, acquired substantial profit from these transactions, some of which profit was redistributed to other projects of the U.S. and of Israel."

Meanwhile, Eugene Hasenfus was providing information to his captors on two Cuban-Americans running the operation in El Salvador. This information was made public and it was not long before journalists managed to identify Raphael Quintero and Felix Rodriguez as the two men described by Hasenfus.

At the beginning of November, newspapers in the United States began running stories about the Iran-Contra conspiracy. On 6th November, President Ronald Reagan told reporters that the story that Robert McFarlane had been negotiating an arms for hostages deal "has no foundation". He also argued that he would not carry out talks with Iran as its government was part of "a new international version of Murder Incorporated".

On 21st November, Casey appeared again before the House Select Committee on Intelligence (HSCI). By this time it was public knowledge about the arms-hostages deal. Casey was asked who was responsible for what one committee member described as this "misguided policy". Casey replied: "I think it was the President". Casey also claimed that this was a National Security Council operation. As Bernard McMahon pointed out, "we came out believing the CIA had acted only in a support role at the direction of the White House".

The following day, two investigators working for Attorney General Edwin Meese, discovered important documents while searching Oliver North's office. These documents revealed that the profits on the Iranian arms deals amounted to $16.1 million. However, the Contras had only received $4 million and at least another $12.1 million had gone missing. It was later established that Richard Secord and his partners had taken at least $6.6 million in profits and commissions.

William J. Casey was now summoned to appear before the House Defense Appropriations Subcommittee. On Monday 8th December, he was questioned about the possibility of Iranian payments being diverted to Afghanistan. Two days later he appeared before the House Foreign Relations Committee (HFRC). He was questioned about when he first knew that money was being diverted from the profits of the hostage-arms deals. Casey claimed that he first heard about it from Edwin Meese. Members of the HFRC pointed out that Roy M. Furmark had already testified that he told casey about the deal as early as the 7th October. Casey was questioned for five and a half hours. One member said that "questioning Bill Casey was like punching a pillow". Another claimed: "He didn't seem to know what was going on in his own agency."

The following day Casey appeared before the House Select Committee on Intelligence (HSCI). Alan Fiers, a colleague at the CIA who also attended the session, remarked: He stumbled and fumbled. at times it seemed he couldn't talk. He had to be carried. He'd start to answer and wave to one of us to take over when his words or his facts failed him."

Casey was due to appear before the HSCI on 16th December. The day before, CIA physician, Dr. Arvel Tharp went to visit Casey in his office. According to Tharp, while he was being examined, Casey suffered a seizure. He was taken to Georgetown University Hospital and was not able to appear before the HSCI. Tharp told Casey he had a brain tumor and that he would have to endure an operation. Casey was not keen and asked if he could have radio therapy instead. However, Tharp was insistent that he needed surgery.

Casey entered the operating room on 18th December. The tumor was removed but during the operation, brain cells were damaged and Casey lost his ability to speak. As his biographer, Joseph E. Persico, points out (The Lives and Secrets of William J. Casey): "one school of rumors ran, the CIA or the NSC or the White House had arranged to have a piece of the brain removed from the man who knew the secrets".

Robert Gates now became acting director of the CIA. He claimed that he was not involved in the Iran-Contra operation. As Lawrence E. Walsh pointed out in Iran-Contra: The Final Report "Gates consistently testified that he first heard on October 1, 1986, from the national intelligence officer who was closest to the Iran initiative, Charles E. Allen, that proceeds from the Iran arms sales may have been diverted to support the contras. Other evidence proves, however, that Gates received a report on the diversion during the summer of 1986 from DDI Richard Kerr. The issue was whether Independent Counsel could prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Gates was deliberately not telling the truth when he later claimed not to have remembered any reference to the diversion before meeting with Allen in October."

William Joseph Casey died on 6th May, 1987. After his death, Oliver North testified that Casey had played an important role in the Irangate Scandal. Lawrence E. Walsh argued in Iran-Contra: The Final Report: "There is evidence that Casey played a role as a Cabinet-level advocate both in setting up the covert network to resupply the contras during the Boland funding cut-off, and in promoting the secret arms sales to Iran in 1985 and 1986."

On this day in 1938 Clarence Darrow died. Darrow was born in Kinsman, Ohio, on 18th April, 1857. His father had originally trained as a Unitarian minister, but lost his faith and Clarence was brought up as an agnostic. An opponent of slavery, Darrow brought up his son as a supporter of reformist politicians such as Horace Greeley and Samuel Tilden. "From my youth I was always interested in political questions. My father, like many others in northern Ohio, had early come under the spell of Horace Greeley... I was fifteen years old when Horace Greeley ran for the presidency. My father was an enthusiastic supporter of Greeley and I joined with him; and well do I remember the gloom and despair that clouded our home when we received the news of his defeat."

After an education at Allegheny College and the University of Michigan Law School, Darrow became a member of the Ohio bar in 1878. For the next nine years he was a typical small-town lawyer. However, in 1887 Darrow moved to Chicago in search of more interesting work. During this period he read the work of radical journalist, Henry George. "During these early years in Chicago I was very much interested in what passes under the name of 'radicalism' and at one time was a pronounced disciple of Henry George. But as I read and pondered about the history of man, as I learned more about the motives that move individuals and communities, I became doubtful of his philosophy. Socialism seemed to me much more logical and profound; Socialism at least recognised that if man was to make a better world it must be through the mutual effort of human units; that it must be by some sort of co-operation that would include all the units of the state. Still, while I was in sympathy with its purposes, I could never find myself agreeing with its methods. I had too little faith in men to want to place myself entirely in the hands of the mass. And I never could convince myself that any theory of Socialism so far elaborated was consistent with individual liberty."

As a young lawyer, Darrow had been impressed by the book Our Penal Machinery and Its Victims by John Peter Altgeld. The two men became close friends and shared a belief that the United States criminal system favoured the rich over the poor. Later Altgeld was elected governor of Illinois and controversially pardoned several men convicted after the Haymarket Bombing.

In 1890 Darrow became the general attorney to the Chicago and North Western Railway. However, during the Pullman Strike Darrow felt sympathy for the trade unions and offered his services to its leaders. Darrow argued in one trial involving union leaders: "Let me tell you, gentlemen, if you destroy the labor unions in this country, you destroy liberty when you strike the blow, and you would leave the poor bound and shackled and helpless to do the bidding of the rich. It would take this country back to the time when there were masters and slaves."

Darrow defended Eugene Debs, president of the American Railway Union, when he was arrested for contempt of court arising from the strike. Although Debs and his fellow trade unionists were convicted, Darrow had established himself as America's leading labour lawyer. Over the next few years Darrow defended several trade union leaders arrested during industrial disputes. Darrow also became involved in the campaign against child labour and capital punishment.

In September 1905, Darrow helped to establish the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Other members included Jack London, Upton Sinclair, Florence Kelley, Jack London, Anna Strunsky, Bertram D. Wolfe, Jay Lovestone, Rose Pastor Stokes and J.G. Phelps Stokes. Its stated purpose was to "throw light on the world-wide movement of industrial democracy known as socialism."

In 1905 William D. Haywood, leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), was charged with taking part in the murder of Frank R. Steunenberg, the former governor of Idaho. Steunenberg was much hated by the trade union movement after using federal troops to help break strikes during his period of office. Over a thousand trade unionists and their supporters were rounded up and kept in stockades without trial.

James McParland, from the Pinkerton Detective Agency, was called in to investigate the murder. McParland was convinced from the beginning that the leaders of the Western Federation of Miners had arranged the killing of Steunenberg. McParland arrested Harry Orchard, a stranger who had been staying at a local hotel. In his room they found dynamite and some wire. McParland helped Orchard to write a confession that he had been a contract killer for the WFM, assuring him this would help him get a reduced sentence for the crime. In his statement, Orchard named Hayward and Charles Moyer (president of WFM). He also claimed that a union member from Caldwell, George Pettibone, had also been involved in the plot. These three men were arrested and were charged with the murder of Steunenberg.

Darrow was employed to defend Hayward, Moyer and Pettibone. The trial took place in Boise, the state capital. It emerged that Harry Orchard already had a motive for killing Steunenberg, blaming the governor of Idaho, for destroying his chances of making a fortune from a business he had started in the mining industry. During the three month trial, the prosecutor was unable to present any information against Hayward, Moyer and Pettibone except for the testimony of Orchard and were all acquitted.

Harrison Gray Otis, the owner of the Los Angeles Times, was a leading figure in the fight to keep the trade unions out of Los Angeles. This was largely successful but on 1st June, 1910, 1,500 members of the International Union of Bridge and Structural Workers went on strike in an attempt to win a $0.50 an hour minimum wage. Otis, the leader of the Merchants and Manufacturers Association (M&M), managed to raise $350,000 to break the strike. On 15th July, the Los Angeles City Council unanimously enacted an ordinance banning picketing and over the next few days 472 strikers were arrested.

On 1st October, 1910, a bomb exploded by the side of the newspaper building. The bomb was supposed to go off at 4:00 a.m. when the building would have been empty, but the clock timing mechanism was faulty. Instead it went off at 1.07 a.m. when there were 115 people in the building. The dynamite in the suitcase was not enough to destroy the whole building but the bombers were not aware of the presence of natural gas main lines under the building. The blast weakened the second floor and it came down on the office workers below. Fire erupted and spread quickly through the three-story building, killing twenty-one of the people working for the newspaper.

The next day unexploded bombs were found at the homes of Harrison Gray Otis and of F. J. Zeehandelaar, the secretary of the Merchants and Manufacturers Association. The historian, Justin Kaplan, has pointed out: "Harrison Gray Otis accused the unions of waging warfare by murder as well as terror.... In editorials that were echoed and amplified across a country already fearful of class conflict, Otis vowed that the supposed dynamiters, who had committed the 'Crime of the Century,' must surely hang and the labor movement in general."

William J. Burns, the detective who had been highly successful working in San Francisco, was employed to catch the bombers. Otis introduced Burns to Herbert S. Hockin, a member of the union executive who was a paid informer of the (M&M). Information from Hockin resulted in Burns discovering that union member Ortie McManigal had been handling the bombing campaign on orders from John J. McNamara, the secretary-treasurer of the International Union of Bridge and Structural Workers. McManigal was arrested and Burns convinced him that he had enough evidence to get him convicted of the Los Angeles Times bombing. McManigal agreed to tell all he knew in order to secure a lighter prison sentence, and signed a confession implicating McNamara and his brother, James B. McNamara. Other names on the list included Frank M. Ryan, president of the Iron Workers Union. According to Ryan the list named "nearly all those who have served as union officers since 1906."

Some believed that it was another attempt to damage the reputation of the emerging trade union movement. It was argued that Harrison Gray Otis and his agents had framed the McNamaras, the object being to cover up the fact that the explosion had really being caused by leaking gas. Darrow was employed by Samuel Grompers, head of the American Federation of Labor, to defend the McNamara brothers. One of Darrow's assistants was Job Harriman, a former preacher turned lawyer.

On 19th November 1911, Darrow and Lincoln Steffens was asked to meet with Edward Willis Scripps at his Miramar ranch in San Diego. According to Justin Kaplan, the author of Lincoln Steffens: A Biography (1974): "Darrow arrived at Miramar with the sure prospect of defeat. He had failed, in his own investigations, to breach the evidence against the McNamaras; on his own, he had even turned up fresh evidence against them; and, in desperation, hoping for a hung jury and a mistrial.... Steffens, who had interviewed the McNamaras in their cell that week, asking for permission to write about them on the assumption that they were guilty; he had even talked to them about changing their plea. Darrow, too, was approaching the same stage in his reasoning. It was tragic, he had to agree with the other two, that the case could not be tried on its true issues, not as murder, but as a 'social crime' that was in itself an indictment of a society in which men believed they had to destroy life and property in order to get an hearing."

Scripps suggested that the McNamaras had committed a selfless act of insurgency in the unequal warfare between workers and owners; after all, what weapons did labour have in this warfare except "direct action". The McNamaras were as "guilty" as John Brown had been guilty at Harper's Ferry. Scripps argued that "Workingmen should have the same belligerent rights in labour controversies that nations have in warfare. There had been war between the erectors and the ironworkers; all right, the war is over now; the defeated side should be granted the rights of a belligerent under international law."

Lincoln Steffens agreed with Scripps and suggested that the "only way to avert class struggle was to offer men a vision of society founded on the Golden Rule and on faith in the fundamental goodness of people provided that they were given half a chance to be good". Steffens offered to try and negotiate a settlement out of court. Darrow accepted the offer as he valued Steffens for "his intelligence and tact, and his acquaintance with people on both sides". This involved Steffens persuading the brothers to plead guilty. Steffens later wrote: "I negotiated the exact terms of the settlement. That is to say, I was the medium of communication between the McNamaras and the county authorities". Steffens met with the district attorney, John D. Fredericks. It was agreed the brothers would change their plea to guilty but offer no confession; the state would withdraw its demand for the death penalty, agree to impose only moderate prison terms, and also agree that there would be no further pursuit of other suspects in the case.

Darrow argued in his autobiography, The Story of My Life (1932): "The one reason that made me most anxious to save their lives was my belief that there was never any intention to kill any one. The Times building was not blown up; it was burned down by a fire started by an explosion of dynamite, which was put in the alley that led to the building. In the statement that was made by J. B. McNamara, at the demand of the State's attorney before the plea was entered, he said that he had placed a package containing dynamite in the alley, arranged the contraption for explosion, and went away. This was done to scare the employees of The Times and others working in non-union shops. Unfortunately, the dynamite was deposited near some barrels standing in the alley that happened to contain ink, which was immediately converted into vapor by the explosion, and was scattered through the building, carrying the fire in every direction."

On 5th December, 1911, Judge Walter Bordwell sentenced James B. McNamara to life imprisonment at San Quentin. His brother, John J. McNamara, who could not be directly linked to the Los Angeles bombing, received a 15 year sentence. Bordwell denounced Steffens for his peacemaking efforts as "repellent to just men" and concluded: "The duty of the court in fixing the penalties in these cases would have been unperformed had it been swayed in any degree by the hypocritical policy favoured by Mr. Steffens (who by the way is a professed anarchist) that the judgment of the court should be directed to the promotion of compromise in the controversy between capital and labour." As he left the court James McNamara said to Steffens: "You see, you were wrong, and I was right".

Although Darrow supported Allied involvement in the First World War he represented several people charged with anti-war activities. Darrow was especially critical of the Espionage Act and the way it was used to imprison left-wing trade union activists. However, he refused to support the Russian Revolution and he told Lincoln Steffens that the Bolshevik leaders would "end up like all the rest".

Darrow's liberal views were based on the belief the social and psychological pressures were mainly responsible for an individual's anti-social behaviour. In 1924 he agreed to take the Leopold-Loeb case, where two wealthy students had kidnapped and murdered a young boy. Darrow insisted that his clients plead guilty and then saved them from the death penalty by using expert witnesses to show how Leopold and Loeb were not completely responsible for their actions.

His old friend Lincoln Steffens claimed that "Darrow handles himself as if he were a musical instrument. He has fought the greatest battles of our day and won them. He can't bear to have a client executed. We call him the attorney for the damned, and he says life isn't worth living!" (Darrow had once said that "had I known what life would be like when I was born, I'd have asked God to let me off.")

Darrow's most famous case was in 1925 when he defended John T. Scopes, a teacher accused of teaching the evolutionary origin of man, rather than the doctrine of divine creation. His main opponent in the case was the former presidential candidate, William Jennings Bryan, who believed the literal interpretation of the Bible. Although it is claimed that Darrow outshone Bryan during the Scopes Trial, Scopes was found guilty.

Darrow also played a prominent role in the Sweet Case (1925-26), where he successfully defended a black family who had used violence against a mob trying to expel them from a white area in Detroit. Darrow also worked on the Scottsboro Case, where nine young black men were falsely charged with the rape of two white women on a train.

Ella Winter, the wife of Lincoln Steffens met Charles Darrow for the first time in 1926. She wrote in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "Clarence Darrow was as picturesque as he was fascinating. His huge head dropped sideways, as if too heavy to carry. His face was carved into deep and wonderful lines, his hulking frame hung loosely inside his clothes, and he hunched his head deep into his shoulders when he made a point, so that you saw no neck at all.... Darrow, craggy, broad-shouldered, slow-speaking and humorous... I was tremendously drawn to him and he was eager to know his old friend's new young wife. Darrow had a great interest in women."

Clarence Darrow, was the author of several books, including Crime, its Cause and Treatment(1925), The Prohibition Mania (1927) and an autobiography, The Story of My Life (1932).

On this day in 1957 Lena Ashwell died. Lena Ashwell was born on a ship on the River Tyne on 28th September, 1872. Her father was the captain of a training ship. When she was a child the family emigrated to Canada. After the death of her mother she returned to Europe where she studied French at Lausanne University before moving to London where she studied singing at the Royal Academy of Music.

Ashwell decided to concentrate on acting and in 1891, she appeared in The Pharisee. This was followed by appearing with Ellen Terry and Henry Irving in King Arthur, by J. Comyns Carr. She also took the lead in Mrs Dane's Defence (1900) and Leah Kleschna (1905).

In 1907 she established her own theatre known as the Kingsway. It is believed that it received financial backing from Muriel De La Warr. Ashwell married the royal obstetrician Henry Simpson in 1908.

In 1908 Lena Ashwell joined forces with Elizabeth Robins, Kitty Marion, Winifred Mayo, Sime Seruya, Edith Craig, Inez Bensusan, Ellen Terry, Lillah McCarthy, Sybil Thorndike, Lily Langtry and Nina Boucicault to establish the Actresses' Franchise League. The first meeting of the AFL took place at the Criterion Restaurant at Piccadilly Circus. The AFL was open to anyone involved in the theatrical profession and its aim was to work for women's enfranchisement by educational methods, selling suffrage literature and staging propaganda plays. The AFL neither supported nor condemned militancy. In 1908 Ashwell appeared in Diana of Dobson's, a play written by Cicely Hamilton.

On the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 the AFL, at the instigation of Lena Ashwell, launched the Women's Theatre Camps Entertainments, which travelled round camps and hospitals. She was one of the founders of the Women's Emergency Corps and honorary treasurer of the British Women's Hospitals, and then took the Lena Ashwell Players to the Western Front.

After the war the Lena Ashwell Players continued as a company that was committed to bringing plays dealing with social issues to audiences in town halls.

On this day in 1963 women's suffrage campaigner Elsie Howey died.

Elsie Howey, the daughter of Gertrude and Thomas Howey, rector of Finningley in Nottinghamshire, on 1st December 1884. She attended St Andrews University between 1902-1904. She lived for a while in Germany where she later claimed "she had first occasion to realise women's position."

Howey joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and in February 1908 she was arrested for taking part in a demonstration outside the House of Commons. She was sentenced to six weeks' imprisonment and released on 18th March.

In May 1908, she joined Mary Blathwayt and Annie Kenney to help at a by-election in Shropshire. Blathwayt wrote in her diary: "This afternoon I helped Annie Kenney make her plans for a West of England campaign, I wrote out lists of towns and dates which are to be sent to Mrs. Pankhurst and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence. This evening Miss Howey went round the town with some steps, and I went with her. And when we came to a crowd she got onto the steps and shouted Keep the Liberal out. Votes for Women".

Elsie Howey was arrested for the second time after taking part in a demonstration outside the home of Herbert Asquith. She was sentenced to three months' imprisonment. On her release she and Vera Wentworth were met at the gates of Holloway Prison and then drawn by 50 women on a carriage to Queen's Hall. On her arrival she was presented with bouquets in the suffragette colours and with illuminated scrolls designed by Sylvia Pankhurst to commemorate their imprisonment.

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence wrote an article in Votes for Women in February 1909: "I say to you young women who have private means or whose parents are able and willing to support you while they give you freedom to choose your vocation. Come and give one year of your life to bringing the message of deliverance to thousands of your sisters... Miss Elsie Howey is honorary organiser in Plymouth. She is the daughter of Mrs. Howey, of Malvern. Mrs. Howey and her two daughters have given generously of all that they have, but the best prized gift is the life-work of this noble girl who has undergone two periods of imprisonment for the sake of women less privileged and happily placed than herself. She is one of our most able and successful organisers, and takes all the duties and responsibilities of our chief officers."

Howey, who was described by the mother of Mary Blathwayt as being "a wonderful speaker" went to work with Annie Kenney who was based in Bristol. During this period she was a visitor to Eagle House at Batheaston. Others who spent time at Blathwayt's house included Christabel Pankhurst, Clara Codd, Constance Lytton, Vera Wentworth, Jessie Kenney, Annie Kenney, Clare Mordan and Helen Watts. Colonel Linley Blathwayt photographed the women. These were then signed and sold at WSPU bazaars. He also invited them to plant a tree to commemorate their prison sentences and hunger strikes.

On 16th April 1909 Elsie Howey rode as Joan of Arc at the head of the procession to welcome Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence on her release from Holloway Prison. On 30th July she was arrested with Vera Wentworth for demonstrating at a meeting held in Penzance by Lord Carrington. They were sentenced to seven days' imprisonment and both women went on hunger strike. Howey fasted for 144 hours and on her release she went to stay at Eagle House at Batheaston.

On 5th September she was involved with Vera Wentworth and Jessie Kenney in assaulting Herbert Asquith and Herbert Gladstone while they were playing golf. Emily Blathwayt was horrified by this increase in violence. On 7th September she wrote in her diary: "We hear of terrible things by the two Hooligans we know, Vera and Elsie and there is a Kenney in it. They made a regular raid on Mr. Asquith breaking a window and using personal violence. Then missiles have been thrown lately through windows during Cabinet Members meetings which might injure or kill innocent persons."

The following day Emily Blathwayt sent a letter to the WSPU headquarters: "Dear Madam, with great reluctance I am writing to ask that my name may be taken off the list as a Member of the W.S.P.U. Society. When I signed the membership paper, I thoroughly approved of the methods then used. Since then there has been personal violence and stone throwing which might injure innocent people. When asked by acquaintances what I think of these things I am unable to say that I approve, and people of my village who have hitherto been full of admiration for the Suffragettes are now feeling very differently. Colonel Linley Blathwayt wrote to Christabel Pankhurst complaining about the behaviour of Elsie Howey and Vera Wentworth and suggested that they would no longer be welcome at Eagle House.

Colonel Blathwayt also wrote letters to Wentworth and Howley about their behaviour. He said that "an attack on one undefended man by three women was an act I did not expect from the Society". According to Emily Blathwayt, they received a "long letter from Vera Wentworth who is very sorry we are grieved but if Mr. Asquith will not receive deputation they will pummel him again." She also claimed that Herbert Gladstone gave Jessie Kenney "a nasty blow in the chest".

Howey was arrested with Constance Lytton on 14th January 1910 and sentenced to six weeks' hard labour. Votes for Women described Howey as: "A devoted honorary organiser who gives the whole of her services and the whole of her life to the Cause. She is a beautiful, refined, and charming girl."

Howey was inactive in 1911 but was arrested again in March 1912 when she took part in the WSPU window-smashing campaign. She was found guilty and sentenced to four months' imprisonment. At the end of 1912 she was back in Holloway Prison for setting-off a fire-alarm. She went on hunger strike and was forcibly fed. Elsa Gye commented that the injuries inflicted during the force-feeding meant that "her beautiful voice was quite ruined." In June 1913 Howey played the role of Joan of Arc at the funeral of Emily Wilding Davison.

Her biographer, Krista Cowman, wrote: "Tired and ill, Elsie vanished from public life when militancy ended in 1914. She remained in Malvern but followed no career, and never fully recovered from the sacrifices she made in the name of the WSPU.

Elsie Howey died on 13 March 1963 at the Court House Nursing Home, Court Road, Malvern, from chronic pyloric stenosis, almost certainly connected to her numerous forcible feedings."

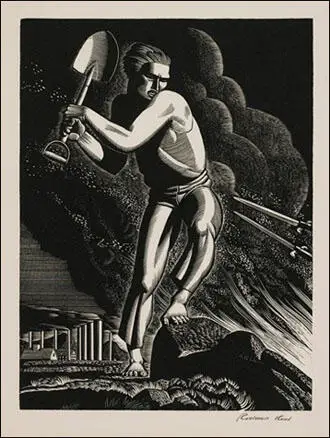

On this day in 1971 Rockwell Kent died. He was born in New York on 21st June 1882. He studied architecture at Columbia University (1900-03) and art at the New York School of Art (1903-04) where he was influenced by Robert Henri and was associated with the social realist Ash Can group of artists. Kent's first one man's show was at the Clausen Galleries in 1908.

Kent was involved with the radical journal, The Masses, and in 1912 was responsible for recruiting Maurice Becker to the staff. Kent left in 1916 with John Sloan and Stuart Davis over a dispute concerning the role of illustrations in the journal.

After spending the winter of 1918 on Fox Island in Alaska he published an illustrated account of his experiences in Wilderness (1920). In the 1920s he established a reputation as an engraver, lithographer and illustrator. He also produced the mural for the General Electric Company Building (1939). His autobiography, It's Me O Lord was published in 1955.

Throughout his life he remained a left-wing activist and was blacklisted as a result of the activities of Joe McCarthy and the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Kent received the Lenin Peace Prize in 1967, a portion of which he donated to North Vietnam.

On this day in 1985 Margaret Thatcher met Mikhail Gorbachev for the first time at the funeral of Konstantin Chernenko. Thatcher's views on the Soviet Union changed after Gorbachev announced his new policy of Perestroika (Restructuring). This heralded a series of liberalizing economic, political and cultural reforms which had the aim of making the Soviet economy more efficient. Gorbachev also introduced policies with the intention of establishing a market economy by encouraging the private ownership of Soviet industry and agriculture.

On the death of Chernenko Gorbachev was elected by the Central Committee as General Secretary of the Communist Party. As party leader he immediately began forcing more conservative members of the Central Committee to resign. He replaced them with younger men who shared his vision of reform.

In 1985 Gorbachev introduced a major campaign against corruption and alcoholism. He also spoke about the need for Perestroika (Restructuring) and this heralded a series of liberalizing economic, political and cultural reforms which had the aim of making the Soviet economy more efficient.

Gorbachev introduced policies with the intention of establishing a market economy by encouraging the private ownership of Soviet industry and agriculture. However, the Soviet authoritarian structures ensured these reforms were ineffective and there were shortages of goods available in shops.

Gorbachev also announced changes to Soviet foreign policy. In 1987 he met with Ronald Reagan and signed the Immediate Nuclear Forces (INF) abolition treaty. He also made it clear he would no longer interfere in the domestic policies of other countries in Eastern Europe and announced the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan. In December 1987 he announced the withdrawal of 500,000 Soviet troops from Central and Eastern Europe and made it clear he would not send in Soviet troops to protect communist states. The following year he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Aware that Gorbachev would not send in Soviet tanks there were demonstrations against communist governments throughout Eastern Europe. Over the next few months the communists were ousted from power in Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, and East Germany.

Gorbachev's attempts to make the Soviet Union a more democratic country made him unpopular with conservatives still in positions of power. In August 1991 he survived a coup staged by hard-liners in the Communist Party. Gorbachev responded by dissolving the Central Committee. However, with the Soviet Union disintegrating into separate states, Gorbachev resigned from office on 25th December, 1995.

On this day in 1995 war hero Odette Sansom died. Odette Brailly was born in Amiens, France, on 28th April 1912. Her father was a soldier in the French Army and was killed during the First World War. Educated at the Convent of Therese in Amiens she married Roy Sansom, a hotel worker, in 1931. The couple moved to London where she gave birth to three children.

Distressed by the occupation of France by the German Army in 1940 she made contact with the Free French forces based in London. As a result she was recruited by the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

In October, 1941, she was sent by boat to France with orders to help establish a new circuit in Burgundy. Over the next few months she worked under Peter Churchill, the SOE's organizer in that part of the country.

On 16th April, 1943, Sansom and Churchill were arrested by Hugo Bleicher of Abwehr. They claimed they were husband and wife and related to Winston Churchill. They hoped that this story would help them receive better treatment while in prison.

Sansom was sent to Fresnes Prison in Paris and while being tortured by the Gestapo she had all her toenails pulled out. On 13th May 1944 the Germans transported Sansom and seven other SOE agents, Yolande Beekman, Eliane Plewman, Vera Leigh, Diana Rowden, Andrée Borrel, Sonya Olschanezky and Madeleine Damerment to Nazi Germany. The following month she was sent to Ravensbruck Concentration Camp.

Sansom continued to claim that she was related to Winston Churchill and in 1945, with the Red Army advancing on Ravensbruck from the east, she persuaded Fritz Suhren, the camp commandant, to drive her to the Allied lines in the west. In 1946 Sansom was awarded the George Cross for bravery and the following year she married Peter Churchill.

The marriage ended in divorce in 1956 and she married Geoffrey Hallowes, a wine importer.