On this day on 12th March

On this day in 1539 Thomas Boleyn, Viscount Rochford, died at Hever Castle. Thomas Boleyn, the second son of Sir William Boleyn, was born in Bilickling Hall in about 1477. His grandfather Sir Geoffrey Boleyn had been lord mayor of London.

His wife, Elizabeth Howard, first daughter of Thomas Howard, second Duke of Norfolk (1443–1524). She gave birth to three children, Mary Boleyn (1498), Anne Boleyn (1499) and George Boleyn (1504). He became a diplomat and he attended the wedding of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon.

Sir Thomas was very ambitious for his children. According to David Starkey: "They were intelligent, ambitious and bound by a fierce mutual affection. Their father recognized their talent and did his best to nurture it." Alison Plowden, the author of Tudor Women (2002), claims that he was particularly interested in the education of his two daughters: "Thomas Boleyn... wanted Mary and Anne to learn to move easily and gracefully in the highest circles and to acquire all the social graces, to speak fluent French, to dance and sing and play at least one instrument, to ride and be able to take part in the field sports which were such an all-absorbing passion with the upper classes, and to become familiar with the elaborate code of courtesy which governed every aspect of life at the top."

Boleyn was a valued participant in royal tournaments. He was the king's opponent at Greenwich Palace in May 1510. "With his linguistic skills, his charm, and his knowledge of horses, hawks, and bowls, Boleyn made an ideal courtier." In 1512 Boleyn was sent on a diplomatic mission by Henry VIII to Brussels. During his trip he arranged for Mary Boleyn to join the household of Margaret, Archduchess of Austria.

In August, 1514, Henry announced that his sister Mary was to marry King Louis XII of France. Mary was eighteen and Louis was fifty-two. Princess Mary left England for France on 2nd October. She was accompanied by a retinue of nearly 100 English ladies-in-waiting. This included Boleyn's daughters, Mary and Anne. The couple were married on 9th October. Mary and Anne were among the six young girls permitted to remain at the French court by the king after he dismissed all Mary's other English attendants the day after the wedding.

After King Louis XII's death, his wife secretly married Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk, on 3rd March 1515. Mary stayed in France. There is some evidence that she had a sexual relationship with King Francis. He boasted of having "ridden her" and described her as "my hackney". A representative of Pope Leo X described her as "a very great infamous whore". As her biographer, Jonathan Hughes, has pointed out, "she seems to have acquired a decidedly dubious reputation."

Anne Boleyn also remained in France but she seems to have avoided the kind of behaviour indulged in by her sister. Members of the Royal Court observed that she learned "dignity and poise". According to the French poet, Lancelot de Carle, "she became so graceful that you would never have taken her for an Englishwoman, but for a Frenchwoman born."

Sir Thomas Boleyn eventually heard the rumours concerning Mary and brought her back to England. Boleyn became a maid of honour to Catherine of Aragon. King Henry VIII had several mistresses. The most important was Bessie Blount and on 15th June 1519, she gave birth to a son. He was named Henry FitzRoy, and was later created Duke of Richmond. After the child's birth, the affair ended. It is believed that his new mistress was Thomas Boleyn's daughter, Mary. The historian, Antonia Fraser, has argued: "The affair repeated the pattern established by Bessie Blount: here once again was a vivacious young girl, an energetic dancer and masker, taking the fancy of a man with an older, more serious-minded wife, no longer interested in such things."

On 4th February 1520 Mary Boleyn married William Carey, a gentleman of the privy chamber. Henry VIII attended the wedding and over the next few years gave Carey several royal grants of land and money. David Loades has pointed out: "Whether this was a marriage of convenience, arranged by the King to conceal an existing affair, or whether she only became his mistress after her marriage, is not clear." In 1523 he named a new ship Mary Boleyn. This is believed that Henry did this to acknowledge Mary as his mistress. One historian has suggested that these "transactions might seem to turn Mary into the merest prostitute, with her husband and father as her pimps".

Thomas Boleyn continued to be used for diplomatic trips. He attended the Field of Cloth of Gold and was involved in the Franco-Imperial conferences organized by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey in 1521. In May 1522 he accompanied Henry VIII to a royal meeting with Emperor Charles V at Canterbury. Later that year he was sent to Spain on a further mission promoting an offensive alliance against France, from which he returned in May 1523. On 18th June 1525 at Bridewell Palace he was elevated to the peerage as Viscount Rochford.

Mary Boleyn gave birth to two children, Catherine (1524) and Henry (1526). Some have argued that Henry was the father of both children. Antonia Fraser, the author of The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1992), has argued against this: "Despite later rumours to the contrary, none of Mary's children were fathered by King Henry: her daughter Catherine Carey and her son Henry Carey, created Lord Hunsdon by his first cousin Queen Elizabeth, were born in 1524 and 1526 respectively when the affair was over. We may be sure that Henry Carey would have been acclaimed with the same joy as Henry Fitzroy, if he had been the King's son."

William Carey died of sweating sickness on 22nd June, 1528. Henry VIII ordered Thomas Boleyn to take Mary under his roof and maintain her, and assigned her the annuity of £100 formerly enjoyed by her husband. By this time Henry was having an affair with Mary's sister, Anne Boleyn. It is not known exactly when this relationship had began. Hilary Mantel has pointed out: "We don't know exactly when he fell for Anne Boleyn. Her sister Mary had already been his mistress. Perhaps Henry simply didn't have much imagination. The court's erotic life seems knotted, intertwined, almost incestuous; the same faces, the same limbs and organs in different combinations. The king did not have many affairs, or many that we know about. He recognised only one illegitimate child. He valued discretion, deniability. His mistresses, whoever they were, faded back into private life. But the pattern broke with Anne Boleyn."

For several years Henry had been planning to divorce Catherine of Aragon. Now he knew who he wanted to marry - Anne. At the age of thirty-six he fell deeply in love with a woman some sixteen years his junior. Henry wrote Anne a series of passionate love letters. In 1526 he told her: "Seeing I cannot be present in person with you, I send you the nearest thing to that possible, that is, my picture set in bracelets ... wishing myself in their place, when it shall please you." Soon afterwards he wrote during a hunting exhibition: "I send you this letter begging you to give me an account of the state you are in... I send you by this bearer a buck killed late last night by my hand, hoping, when you eat it, you will think of the hunter."

Philippa Jones has suggested in Elizabeth: Virgin Queen? (2010) that refusing to become his mistress was part of Anne's strategy to become Henry's wife. She had learnt from the experiences of her sister that it was not a very good idea to give him what he wanted straight away: "Anne frequently commented in her letters to the King that although her heart and soul were his to enjoy, her body would never be. By refusing to become Henry's mistress, Anne caught and retained his interest. Henry might find casual sexual gratification with others, but it was Anne that he truly wanted." Historians have suggested that Anne was trying to persuade Henry to marry her: "Henry found her not easily tamed, for it is clear that she had the strength of will to withhold her favours until she was sure of being made his queen... All the same it must remain somewhat surprising that sexual passion should have turned a conservative, easy-going, politically cautious ruler into a revolutionary, head-strong, almost reckless tyrant. Nothing else, however, will account for the facts."

Anne's biographer, Eric William Ives, has argued: "At first, however, Henry had no thought of marriage. He saw Anne as someone to replace her sister, Mary, who had just ceased to be the royal mistress. Certainly the physical side of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon was already over and, with no male heir, Henry decided by the spring of 1527 that he had never validly been married and that his first marriage must be annulled.... However, Anne continued to refuse his advances, and the king realized that by marrying her he could kill two birds with one stone, possess Anne and gain a new wife."

Henry sent a message to the Pope Clement VII arguing that his marriage to Catherine of Aragon had been invalid as she had previously been married to his brother Arthur. Henry relied on Cardinal Thomas Wolsey to sort the situation out. During negotiations the Pope forbade Henry to contract a new marriage until a decision was reached in Rome. With the encouragement of Anne, Henry became convinced that Wolsey's loyalties lay with the Pope, not England, and in 1529 he was dismissed from office. Wolsey blamed Anne for his situation and he called her "the night Crow" who was always in a position to "caw into the king's private ear". Had it not been for his death from illness in 1530, Wolsey might have been executed for treason.

Henry VIII continued to reward Viscount Rochford. This included a grant of the revenues of the see of Durham. It was now clear that he was one of Henry's small inner ring of councillors. On 8th December 1529 he was promoted earl of Wiltshire and earl of Ormond. On 24th January 1530 the new earl replaced Cuthbert Tunstall, bishop of Durham, as lord privy seal. Whitehall Palace was rebuilt for Anne Boleyn, and in 1531 her father was allocated a set of rooms there.

Henry's previous relationship with Mary Boleyn was also causing him problems in Rome. As she was the sister of the woman who he wanted to marry, Anne Boleyn. It was pointed out that "this placed him in exactly the same degree of affinity to Anne as he insisted that Catherine was to him". However, when Henry discovered that Anne was pregnant, he realised he could not afford to wait for the Pope's permission. As it was important that the child should not be classed as illegitimate, arrangements were made for Henry and Anne to get married. King Charles V of Spain threatened to invade England if the marriage took place, but Henry ignored his threats and the marriage went ahead on 25th January, 1533. It was very important to Henry that his wife should give birth to a male child. Without a son to take over from him when he died, Henry feared that the Tudor family would lose control of England.

Elizabeth was born on 7th September, 1533. Henry expected a son and selected the names of Edward and Henry. While Henry was furious about having another daughter, the supporters of his first wife, Catherine of Aragon were delighted and claimed that it proved God was punishing Henry for his illegal marriage to Anne. Retha M. Warnicke, the author of The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn (1989) has pointed out: "As the king's only legitimate child, Elizabeth was, until the birth of a prince, his heir and was to be treated with all the respect that a female of her rank deserved. Regardless of her child's sex, the queen's safe delivery could still be used to argue that God had blessed the marriage. Everything that was proper was done to herald the infant's arrival."

Henry VIII continued to try to produce a male heir. Unfortunately, Anne Boleyn, had two miscarriages. Viscount Rochford found himself less influencial as a result of Anne being able to produce a son. Anne was pregnant again when she discovered Jane Seymour sitting on her husband's lap. Anne "burst into furious denunciation; the rage brought on a premature labour and was delivered of a dead boy." What is more, the baby was badly deformed. (30) This was a serious matter because in Tudor times Christians believed that a deformed child was God's way of punishing parents for committing serious sins. Henry VIII feared that people might think that the Pope Clement VII was right when he claimed that God was angry because Henry had divorced Catherine and married Anne.

Henry now approached Thomas Cromwell about how he could get out of his marriage with Anne. He suggested that one solution to this problem was to claim that he was not the father of this deformed child. On the king's instruction Cromwell was ordered to find out the name of the man who was the true father of the dead child. Philippa Jones has pointed out: "Cromwell was careful that the charge should stipulate that Anne Boleyn had only been unfaithful to the King after the Princess Elizabeth's birth in 1533. Henry wanted Elizabeth to be acknowledged as his daughter, but at the same time he wanted her removed from any future claim to the succession."

In April 1536, a Flemish musician in Anne's service named Mark Smeaton was arrested. He initially denied being the Queen's lover but later confessed, perhaps tortured or promised freedom. Another courtier, Henry Norris, was arrested on 1st May. Sir Francis Weston was arrested two days later on the same charge, as was William Brereton, a Groom of the King's Privy Chamber. Anne's brother, George Boleyn was also arrested and charged with incest.

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer declared Anne's marriage to Henry null and void on 17th May 1536, and according to the imperial ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, the grounds for the annulment included the king's previous relationship with Mary Boleyn. However, this information has never been confirmed. Later that day George Boleyn was executed.

Anne went to the scaffold at Tower Green on 19th May, 1536. The Lieutenant of the Tower reported her as alternately weeping and laughing. The Lieutenant assured her she would feel no pain, and she accepted his assurance. "I have a little neck," she said, and putting her hand round it, she shrieked with laughter. The "hangman of Calais" had been brought from France at a cost of £24 since he was a expert with a sword. This was a favour to the victim since a sword was usually more efficient than "an axe that could sometimes mean a hideously long-drawn-out affair."

Anne Boyleyn's last words were: "Good Christian people... according to the law I am judged to die, and therefore I will speak nothing against it... I pray God save the King, and send him long to reign over you... for to me he was always a good, a gentle, and sovereign Lord."

After the executions of his son and daughter Thomas Boleyn lost the office of lord privy seal to Thomas Cromwell, the agent of their fall. He therefore became the only nobleman dismissed from one of the great offices of state "by the mature Henry VIII apart from those who were also condemned as traitors". Over the next couple of years he lost all his titles but his English earldom (now without an heir).

On this day in 1878 Mary Sophia Allen, the daughter of the manager of the Great Western Railway, was born in Cardiff on 12th March, 1878. Educated at Princess Helena College in Ealing, she joined the Women's Political and Social Union (WSPU) after meeting Annie Kenney. Her father gave her an ultimatum to either give up her involvement in the suffragette movement or to leave the house. She left but her father continued to support her financially.

In February 1909 she was a member of the WSPU deputation to the House of Commons. She was one of the 28 women arrested and was sentenced to a month's imprisonment in Holloway. On her release she was appointed as WSPU organiser in Cardiff.

During the summer of 1908 the WSPU introduced the tactic of breaking the windows of government buildings. On 30th June suffragettes marched into Downing Street and began throwing small stones through the windows of the Prime Minister's house. As a result of this demonstration, twenty-seven women were arrested and sent to Holloway Prison. This included Mary Allen.

Marion Wallace-Dunlop was a fellow prisoner. Christabel Pankhurst later reported: "Miss Wallace Dunlop, taking counsel with no one and acting entirely on her own initiative, sent to the Home Secretary, Mr. Gladstone, as soon as she entered Holloway Prison, an application to be placed in the first division as befitted one charged with a political offence. She announced that she would eat no food until this right was conceded." She refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her after fasting for 91 hours. Soon afterwards other imprisoned suffragettes, including Mary Allen, adopted the same strategy. Unwilling to release all the imprisoned suffragettes, the prison authorities force-fed these women on hunger strike.

In August 1909 she received a hunger-strike medal from Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), she was the first woman to be awarded this medal. In November 1909 she was arrested for breaking the windows of the Bristol Liberal Club during a visit made by Winston Churchill. She was sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment and after going on hunger strike she was forcibly fed.

Grace Roe remarked that at this time Mary Allen was "very feminine, very delicate". Mary Allen recalled that her digestion had been permanently affected and she was forbidden by Emmeline Pankhurst to take part in any further militant activity.

In February 1912 she became organizer of the Hastings branch of the WSPU and in early 1914 she replaced Lucy Burns as organizer in Edinburgh. On 6th May Christabel Pankhurst wrote to Janie Allan that "in Edinburgh a small handful of people... are decidedly cantankerous, and the person who is organising for the time being is made to feel the effect of this. These people criticise Miss Mary Allen."

Like most members of the WSPU, Allen agreed to the decision to give full support to the British war effort during the First World War. According to Joan Lock, the author of The British Policewoman (1979): "She (Mary Allen) was invited to join a needlework guild, a prospect which filled her with horror: she wanted action. While in this state of limbo, she overheard two people on a bus discussing the risible idea of women police. Mary was enchanted by the notion and immediately investigated and volunteered.

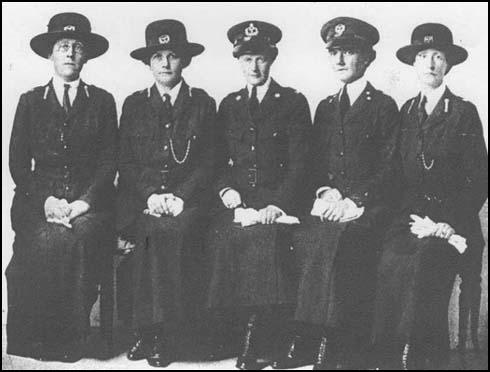

In September 1914, Nina Boyle founded the Women Police Volunteers. The following year Margaret Damer Dawson became Commandant and Allen became Sub-Commandant. Allen argued that it was her experience in the WSPU that made her realise how necessary it was that women when arrested should not "be handled by men."

The government had always opposed the idea of police women but with large numbers of policemen joining the British Army, it was considered a good idea to have women volunteers to help run the service. Another reason that Dawson's proposal was accepted was that her members were willing to work without pay.

Mary Sophia Allen later remarked in her book, The Pioneer Policewoman, that: "A sense of humour had kept me from any bitterness. I was quite as enthusiastically ready to work with and for the police as I had been prepared, if necessary, to enter into combat with them."

In February 1915 Allen and Margaret Damer Dawson renamed her organisation, the Women's Police Service (WPS). At first the WPS concentrated its work in the London area. Wearing a dark-blue uniform, the WPS were assigned responsibilities such as looking after the welfare of refugees. Later that year, Allen was sent to sort out problems in Grantham and Hull. Both towns had army camps and local people were complaining about drunken behaviour and a growth in prostitution.

According to Rebecca Jennings, the author of A Lesbian History of Britain (2007): "Mary Allen's enthusiasm was shared by Margaret Damer Dawson, and the two soon established a close professional and personal relationship, living together in London between 1914 and 1920."

When the Armistice was signed, there were 357 members of the Women's Police Service. Margaret Damer Dawson and Allen, asked the Chief Commissioner, Sir Nevil Macready, to make them a permanent part of his force. He refused, saying that the women were "too educated" and would "irritate" male members of the force. Macready instead decided to recruit and train his own women. However, both Dawson and Allen were awarded the OBE for services to their country during wartime.

When ill-health forced Margaret Damer Dawson to retire in 1920, Allen became the new Commandant of the Women Police Service. In February, 1920, Mary Allen and four of her members were charged with "impersonating police officers". It was claimed that their uniforms were too similar to that of the one worn by the Metropolitan Women Police Patrols. After a four-day hearing Macready won his case and the WPS were forced to change its uniform and its name to the Women's Auxiliary Service.

Rebecca Jennings has argued that: "When Dawson died in 1920, Allen was a major beneficiary in her will, continuing to live in Dawson's house, Danehill, throughout the 1930s and beginning a relationship in the early 1920s with another former WPS officer Miss Helen Tagart."

In 1922 Allen spent time in Cologne where she trained German women for police work. During the 1926 General Strike she helped to keep the road transport services running. According to her biographer, Vera Di Campli San Vito: "In 1927 she founded and edited the Policewoman's Review, which ran until 1937. It was here, in December 1933, that she advertised for recruits to her newly formed women's reserve, the object of which was to train women for service in any national emergency."

Allen was a frequent visitor to Nazi Germany and after meeting Adolf Hitler in 1934 and became one of his most fervent admirers. In a discussion with Hermann Goering she was very pleased when he said that policewomen should wear uniform. Even when on official duties with the Women's Auxiliary Service she wore Nazi style jack-boots.

Mary Sophia Allen was an active supporter of General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist Army during the Spanish Civil War. She was also Chief Women's Officer of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) and a member of the the Right-Club. The historian, Julie V. Gottlieb, has argued: "Allen was a prominent supporter of Mosley's British Union, a movement she claimed she had joined due to her sympathy for its anti-war policy." In 1940 she contributed a series of articles for Action, the organ of the BUF.

Her extreme right-wing views made her unpopular with some members of the Women's Auxiliary Service and she was forced to leave the movement with the approach of the Second World War. According to Helena Wojtczak: "Mary Allen became increasingly eccentric, and her apparent support for Hitler and Goering led to questions about whether she should be interned in 1940." Although she was not interned, her membership of the British Union of Fascists resulted in a suspension order under defence regulation 18B on 11th July 1940.

Mary Allen, who wrote several books, including The Pioneer Policewoman (1925), Woman at the Crossroads (1934) and Lady in Blue (1936), died in the Birdhurst Nursing Home, 4 Birdhurst Road, Croydon, of cerebral thrombosis and cerebral arteriosclerosis on 16th December 1964.

On this day in 1871 Kitty Marion (Katherina Schafer) was born in Westphalia, Germany. Her mother died when she was two and her stepmother when she was six, both of tuberculosis. Her childhood was spent moving between her father, "a strict disciplinarian with a fierce, violent, and evidently uncontrollable temper".

In 1886 she moved to England to be with her sister, Dora. After learning English she adopted the name Kitty Marion and became an actress. In 1889 she was engaged for the pantomime season in Glasgow. According to her biographer, Vivien Gardner: "Her first job was as a chorus member in Robinson Crusoe at the Theatre Royal, Glasgow. Between 1889 and 1903, adopting the name Kitty Marion, she developed a modest but successful career in provincial touring theatre as a singer and dancer in musical comedy and pantomime, graduating from the chorus to minor named roles."

Over the next few years she became a star of the musical hall and she was billed as the "Refined Vocal Comedienne". In 1899 she appeared at the Prince of Wales Theatre in Liverpool, on the same bill as Vesta Tilley. In her autobiography she complained about the "casting couch" tactics of music-hall agents and this was one of the factors that encouraged her to join the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1908.

Kitty Marion took a keen interest in politics and in 1908 joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). She moved to Hartfield in East Sussex and was an active member of the WSPU branch in Brighton. In June she was arrested during a demonstration outside the House of Commons. She later recalled: "Two policemen, one on each arm, quite unnecessarily pinching and bruising the soft underarm, with the third often pushing at the back, would run us along and fling us, causing most women to be thrown to the ground."

Kitty Marion was a supporter of direct action and in July 1909 she was arrested and found guilty of throwing stones at a post office in Newcastle. She was sentenced to a month's imprisonment, went on hunger strike, and was forcibly fed. (5) She barricaded herself in her cell and set fire to her mattress as a protest at her treatment at the hands of the doctors who she described as the "dirty, cringing doormats of the government".

Later that year Kitty Marion joined Elizabeth Robins in helping to form the Actresses' Franchise League. The AFL was open to anyone involved in the theatrical profession and its aim was to work for women's enfranchisement by educational methods, selling suffrage literature and staging propaganda plays. Other actresses who joined included Winifred Mayo, Sime Seruya, Edith Craig, Inez Bensusan, Ellen Terry, Lillah McCarthy, Sybil Thorndike, Vera Holme, Lena Ashwell, Christabel Marshall, Lily Langtry and Nina Boucicault.

In October 1909 she joined forces with Constance Lytton, Jane Brailsford and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and wrote a letter to The Times saying: "We want to make it known that we shall carry on our protest in our prison cells. We shall put before the Government by means of the hunger-strike four alternatives: to release us in a few days; to inflict violence upon our bodies; to add death to the champions of our cause by leaving us to starve; or, and this is the best and only wise alternative, to give women the vote."

Kitty Marion continued to work as an actress and was a significant figure in the Variety Artists' Federation and its campaign against of theatrical agents who she claimed were sometimes involved in the "white slave trade". As Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Women's Suffragette Movement: A Reference Guide (1999), pointed out: "She received a WSPU hunger strike medal in a ceremony at the Albert Hall on 9 December and then went on to do the Christmas pantomime season."

During the 1910 General Election the NUWSS organised the signing petitions in 290 constituencies. They managed to obtain 280,000 signatures and this was presented to the House of Commons in March 1910. With the support of 36 MPs a new suffrage bill was discussed in Parliament. The WSPU suspended all militant activities and on 23rd July they joined forces with the NUWSS to hold a grand rally in London. When the House of Commons refused to pass the new suffrage bill, the WSPU broke its truce on what became known as Black Friday on 18th November, 1910, when its members clashed with the police in Parliament Square. Kitty Marion was arrested during this demonstration but she was released without charge.

Kitty Marion toured the country giving lectures and musical performances. She was billed as the "Music Hall Artiste and Militant Suffragette" and after one meeting in Colchester it was reported: "The awe experienced by the audience was quickly succeeded by delight, for the lady proved a charming vocalist".

In November 1911 she was again arrested outside the House of Commons after taking part in the protest following the defeat of the Conciliation Bill, and was sentenced to 21 days' imprisonment. When in Holloway Prison she again went on hunger-strike and was forced-fed. A friend, Mary Leigh, described what it was like to experience this form of punishment: "On Saturday afternoon the wardress forced me onto the bed and two doctors came in. While I was held down a nasal tube was inserted. It is two yards long, with a funnel at the end; there is a glass junction in the middle to see if the liquid is passing. The end is put up the right and left nostril on alternative days. The sensation is most painful - the drums of the ears seem to be bursting and there is a horrible pain in the throat and the breast. The tube is pushed down 20 inches. I am on the bed pinned down by wardresses, one doctor holds the funnel end, and the other doctor forces the other end up the nostrils. The one holding the funnel end pours the liquid down - about a pint of milk... egg and milk is sometimes used."

Christabel Pankhurst decided that the WSPU needed to intensify its window-breaking campaign. On 1st March, 1912, a group of suffragettes volunteered to take action in the West End of London. The Daily Graphic reported the following day: "The West End of London last night was the scene of an unexampled outrage on the part of militant suffragists.... Bands of women paraded Regent Street, Piccadilly, the Strand, Oxford Street and Bond Street, smashing windows with stones and hammers."

Kitty Marion recalls in her autobiography that she broke windows of the Silversmiths' Association and at Sainsbury's at 134 Regent Street. She was arrested, found guilty and sentenced to six month's imprisonment. Holloway Prison was full so Marion and 23 other members of the WSPU were sent to Winson Green Prison in Birmingham. She again went on hunger-strike and she was released after 10 days.

In July 1912, the WSPU began organizing a secret arson campaign. According to Sylvia Pankhurst: "Women, most of them very young, toiled through the night across unfamiliar country, carrying heavy cases of petrol and paraffin. Sometimes they failed, sometimes succeeded in setting fire to an untenanted building - all the better if it were the residence of a notability - or a church, or other place of historic interest."

Kitty Marion decided she would join this campaign: "I was becoming more and more disgusted with the struggle for existence on commercial terms of sex … I gritted my teeth and determined that somehow I would fight this vile, economic and sex domination over women which had no right to be, and which no man or woman worthy of the term should tolerate."

In July 1912, the WSPU began organizing a secret arson campaign. According to Sylvia Pankhurst: "Women, most of them very young, toiled through the night across unfamiliar country, carrying heavy cases of petrol and paraffin. Sometimes they failed, sometimes succeeded in setting fire to an untenanted building - all the better if it were the residence of a notability - or a church, or other place of historic interest."

Kitty Marion decided she would join this campaign: "I was becoming more and more disgusted with the struggle for existence on commercial terms of sex … I gritted my teeth and determined that somehow I would fight this vile, economic and sex domination over women which had no right to be, and which no man or woman worthy of the term should tolerate."

Fern Riddell has pointed out: "Kitty Marion's hand is evident in attacks from Manchester to Portsmouth; the scope of her attacks overlays neatly into areas she had become well acquainted with during her music hall and theatrical days, which afforded her the luxury of an already established network of lodging houses and local knowledge, allowing her to visit areas and conduct militant activity."

Occasionally they were caught and convicted, usually they escaped. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes.

Christabel Pankhurst pointed out: "Perhaps the Government will realise now that we mean to fight to the bitter end … If men use explosives and bombs for their own purpose they call it war, and the throwing of a bomb that destroys other people is then described as a glorious and heroic deed. Why should a woman not make use of the same weapons as men. It is not only war we have declared. We are fighting for a revolution."

In 1913 the WSPU arson campaign escalated and railway stations, cricket pavilions, racecourse stands and golf clubhouses being set on fire. Slogans in favour of women's suffrage were cut and burned into the turf. Suffragettes also cut telephone wires and destroyed letters by pouring chemicals into post boxes. Marion was a leading figure in the WSPU arson campaign and she was responsible for setting fire to Levetleigh House in St Leonards in April 1913.

From a scrapbook she kept it seems that Kitty Marion also set fire to a train, left standing between Hampton Wick and Teddington on 26th April: "The train was afterwards driven into Teddington Station, where an examination resulted in the discovery of inflammable materials in almost every set of coaches. Among the articles found in the train were partly-burnt candles, four cans of petroleum, three of which had been emptied of their contents, a lady's dressing case containing a quantity of cotton wool, and packages of literature dealing with the woman suffrage movement. Newspaper cuttings of recent suffragette outrages were also found scattered about the train … The method adopted was very simple. First the cushions were saturated with petroleum, and then small pieces of candle were lighted immediately under the seats."

Two months later Kitty Marion and 26 year old Clara Giveen were told that the Grand Stand at the Hurst Park racecourse "would make a most appropriate beacon". The women returned to a house in Kew. A police constable who had been detailed to watch the house, saw the two women return and during the course of the next morning they were arrested. Their trial began at Guildford on 3rd July. She was found guilty and sentenced to three years' penal servitude. She went on hunger strike and was released under the Cat & Mouse Act. She was taken to the WSPU nursing home, into the care of Dr. Flora Murray and Catherine Pine.

As soon as she recovered she went out and broke a window of the Home Office. She was arrested and taken back to Holloway Prison. After going on hunger strike for five days she was again released to a WSPU nursing home. According to her own account, she now set fire to various houses in Liverpool (August, 1913) and Manchester (November, 1913). These incidents resulted in a series of further terms of imprisonment during which force-feeding occurred. It has been calculated that Kitty Marion endured 232 force-feedings in prison while on hunger strike.

Elizabeth Robins disapproved of Kitty Marion's arson campaign but she wrote a circular letter to over 100 leading figures asking them to bring an end to these force-feedings. Robins and Octavia Wilberforce used their 15th century farmhouse at Backsettown, near Henfield, as a hospital and helped her recover from her various spells in prison and the physical effects of going on hunger strike. On 31st May 1914, with the help of Mary Leigh, she escaped to Paris.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

Kitty Marion was one of those members of the Women's Social and Political Union who disagreed with the policy of ending militant activities. She resumed her career as an actress but continued to campaign for the vote. As she had been born in Germany, the government decided to deport her from Britain. After protests from figures such as Constance Lytton and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, she was allowed to go to the United States.

In America she immediately became involved in politics and worked with Margaret Sanger, Lou Rogers and Cornelia Barns in publishing the Birth Control Review. She was arrested several times for violating obscenity laws in New York, and was imprisoned for 30 days in 1918. While in prison Kitty Marion met two other radicals, Mollie Steimer and Agnes Smedley. In 1921 Marion joined Sanger in establishing America's first birth-control clinic. However, the clinic in Brooklyn was closed by the police.

Kitty Marion, wrote an autobiography about her experiences but it was never published. In 1930 she moved to London and gave a copy to the Fawcett Library. She worked with Edith How-Martyn at the Birth Control International Centre. but later returned to New York City and lived there until her death at the Sanger Nursing Home on 9th October 1944.

On this day in 1915 Isabella Ford attacks the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) policy of support for the First World War. The women's movement was split over the issue of what role women should play during the war. The leadership of the Women Social & Political Union was willing to do whatever was necessary to defeat Germany. Millicent Fawcett of the NUWSS urged her members to concentrate on relief work. Others like Isabella Ford and Helena Swanwick argued that the women's movement should use its energies to try and secure a ceasefire. As the war went on Isabella found herself more and more isolated and in 1915 was forced to resign from the executive committee of the NUWSS. For the rest of her life, Ford concentrated her efforts helping the peace movement. In the years, 1919, 1920, 1921 and 1922 Ford was a delegate to the Women's International League Congress.

On this day in 1920 the Kapp Putsch begins. In March 1920, according to the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, the Germans were obliged to dismiss between 50,000 and 60,000 men from the armed forces. Among the units to be disbanded was a naval brigade commanded by Captain Herman Ehrhardt, a leader of a unit of Freikorps. The brigade had played a role in crushing the Bavarian Socialist Republic in May, 1919.

On the evening of 12th March, 1920, the Ehrhardt brigade went into action. He marched 5,000 of his men twelve miles from their military barracks to Berlin. The Minister of Defence, Gustav Noske, had only 2,000 men to oppose the rebels. However, the leaders of the German Army refused to put down the rebellion. General Hans von Seeckt informed him "Reichswehr does not fire on Reichswehr." Noske contacted the police and security officers but they had joined the coup themselves. He commented: "Everyone has deserted me. Nothing remains but suicide." However, Noske did not kill himself and instead fled to Dresden with Friedrich Ebert. However, the local military commander, General George Maercker refused to protect them and they were forced to travel to Stuttgart.

Captain Herman Ehrhardt met no resistance as they took over the ministries and proclaimed a new government headed by Wolfgang Kapp, a right-wing politician. Berlin had been seized from the German Social Democrat government. However, the trade union leaders refused to flee and Carl Legien called for a general strike to take place. As Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982), has pointed out: "The appeal had an immediate impact. It went out at 11am on the day of the coup, Saturday 13 March. By midday the strike had already started. Its effects could be felt everywhere in the capital within 24 hours, despite it being a Sunday. There were no trains running, no electricity and no gas. Kapp issued a decree threatening to shoot strikers. It had no effect. By the Monday the strike was spreading throughout the country - the Ruhr, Saxony, Hamburg, Bremen, Bavaria, the industrial villages of Thuringia, even to the landed estates of rural Prussia."

Louis L. Snyder has argued: "The strike was effective because without water, gas, electricity, and transportation, Berlin was paralyzed." A member of the German Communist Party (KPD) argued: "The middle-ranking railway, post, prison and judicial employees are not Communist and they will not quickly become so. But for the first time they fought on the side of the working class." Five days after the putsch began, Wolfgang Kapp announced his resignation and fled to Sweden.

Richard M. Watt, the author of The Kings Depart: The Tragedy of Germany - Versailles and the German Revolution (1973), has argued: "The Kapp putsch was brought to an end by a combination of the Chancellor Kapp's total incompetence and the astonishing effectiveness of a general strike which the socialists called." Chris Harman interprets these events slightly differently. In The Lost Revolution (1982) he comments: "The putsch was, in fact, confronted by something far more threatening. In place after place workers turned the strike into an armed assault on the power behind the putsch - the structure of armed power built up so laboriously by Noske and the High Command in the previous 14 months... In three parts of Germany - the industrial heartland of the Ruhr, the mining and industrial areas of central Germany, and the northern region between Lubeck and Wismar - the armed working class effectively took power into its own hands."

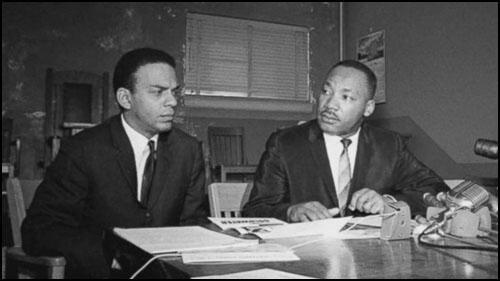

On this day in 1932 Andrew Young was born in New Orleans. After graduating from Howard University in 1951 Young entered the Hartford Theological Seminary. Ordained in 1955, Young served as a pastor in Marion, Alabama and Thomasville and Beachton, Georgia.

Young joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and became increasingly active in the civil rights movement. He became executive director of the SCLC in 1964 and three years later, chairman of the Atlanta Community Relations Commission.

A member of the Democratic Party, Young unsuccessfully ran for Congress in 1970. Two years later he won the seat and over the next four years became a leading spokesman in Congress for African American civil rights. An opponent of the Vietnam War, Young's main concern was to protect the funding of social programs.

In 1976 President Jimmy Carter appointed Young as the country's ambassador to the United Nations. His political views made him popular with the leaders of the Third World but he was forced to resign in 1979 after it became known he had been having meetings with representatives of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

Young returned to political office in 1981 when he was elected mayor of Atlanta. Re-elected in 1985, Young held the post until 1990. Later that year he failed in his attempt to become governor of Georgia.

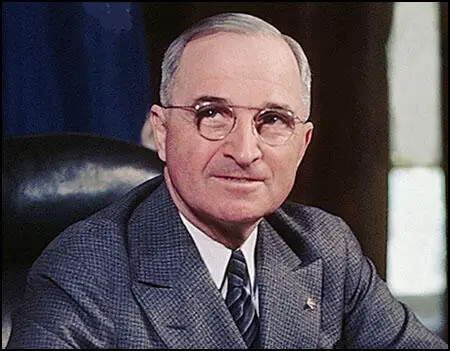

On this day in 1947, Harry S. Truman, announced details to Congress of what eventually became known as the Truman Doctrine. In his speech he pledged American support for "free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures". This speech also included a request that Congress agree to give military and economic aid to Greece in its fight against communism. Truman asked for $400,000,000 for this aid programme. He also explained that he intended to send American military and economic advisers to countries whose political stability was threatened by communism.

On this day in 1973 women's suffrage campaigner Mary Gawthorpe died.

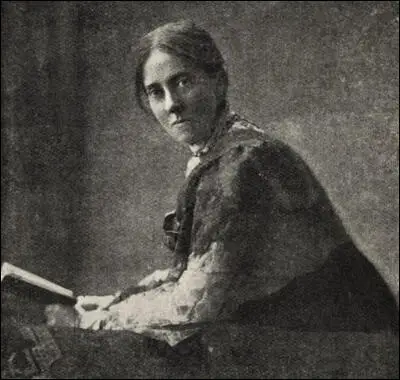

Mary Gawthorpe, the third of the five children of John Gawthorpe, leather worker in Leeds, and Anne Mountain, was born at 5 Melville Street, on 12th January 1881. Her mother had done well at school but her family was extremely poor so from the age of ten had to work in the local textile mill. She had wanted to be a teacher and was determined to make sure her daughter finished her education.

At the age of thirteen Mary became a pupil teacher in the local Church of England school. Annie wanted her daughter to go to college but family finances meant that this was not possible. Instead, Mary worked during the day and studied in the evening and at weekends. Mary qualified as a schoolteacher just before her twenty-first birthday.

In 1901 Mary became friendly with Tom Garrs, a compositor on the Yorkshire Post. Tom was an active member of the Independent Labour Party and Mary began going to meetings with him. Mary Gawthorpe became converted to socialism and she soon developed a reputation as an extremely good public speaker. Mary also became a leading figure in the Leeds branch of the National Union of Teachers.

Mary Gawthorpe was a strong supporter of women's rights and with the help of her friends, Isabella Ford, and Ethel Annakin formed a Leeds branch of the Nation Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. Mary was also active in the Women's Labour League. However, Mary gradually became disillusioned with the Labour Party's failure to organize men to help win the vote for women. In February 1906, Mary met Christabel Pankhurst after she spoke at a meeting in Leeds. Christabel told Mary that: "The further one goes the plainer one sees that men (even Labour men) think more of their own interests than of ours."

Mary joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in October 1905 after reading about the arrest and imprisonment of Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney in Manchester. Tom Garrs disagreed with the militant activities of the WSPU and as a result of this disagreement, the couple parted.

In 1906 Mary gave up her job as a teacher and became the full-time organizer of the WSPU in Leeds. In October she was arrested with Dora Montefiore and Minnie Baldock during a demonstration outside the House of Commons and was sentenced to two months' imprisonment. After being released from Holloway Prison she became one of the WSPU's main speakers at rallies and demonstrations.

Mary suffered from poor health and in February 1907 she was operated on by Louisa Garrett Anderson for appendicitis. After leaving hospital she spent her convalescence with Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence at their home in Surrey. They also took Mary and Annie Kenney to Italy.

The WSPU organised a mass meeting to take place on 21 June 1908 called Women's Sunday at Hyde Park. The leadership intended it "would out-rival any of the great franchise demonstrations held by the men" in the 19th century. Sunday was chosen so that as many working women as possible could attend. It is claimed that it attracted a crowd of over 300,000. At the time, it was the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. Speakers included Mary Gawthorpe, Gladice Keevil, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Jennie Baines, Rachel Barrett, Marie Brackenbury, Georgina Brackenbury, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Marie Naylor, Flora Drummond and Edith New.

Mary Gawthorpe also organised another successful rally at Heaton Park in Manchester that drew over 150,000 people. Her friend, Sylvia Pankhurst commented: "Mary Gawthorpe was a winsome merry creature, with bright hair and laughing hazel eyes, a face fresh and sweet as a flower, the dainty ways of a little bird, and having with all a shrewd tongue and so sparkling a fund of repartee, that she held dumb with astonished admiration, vast crowds of big, slow-thinking workmen and succeeded in winning to good-tempered appreciation the stubbornness opponents." Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy added: "Mary Gawthorpe... is a splendid speaker, full of humour, brilliant and lucid."

In 1909 Mary Gawthorpe heckled a speech given by Winston Churchill. Mary was badly beaten by stewards at the meeting and suffered severe internal injuries. Mary was also imprisoned several times while working for the WSPU. Hunger strikes and force-feeding badly damaged her health and in 1912 she had to abandon her active involvement in the movement.

Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999) has pointed out: "She (Mary Gawthorpe) went to Manchester to implement there a WSPU decision to hold large meetings in the principle cities in order to capitalize on the publicity and success of Hyde Park. She stayed as chief organizer for the WSPU in Lancashire until ill-health forced her to retire at the end of September 1910."

In March 1911 Dora Marsden and her close friend, Grace Jardine, went to work for the Women's Freedom League newspaper, The Vote. Marsden attempted to persuade the WFL to finance a new feminist journal. When this proposal was refused, Marsden left the journal. She now joined forces with Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe to establish her own journal. Charles Granville, agreed to become the publisher. On 23rd November, 1911, they published the first edition of The Freewoman.

Mary Humphrey Ward, the leader of Anti-Suffrage League argued that the journal represented "the dark and dangerous side of the Women's Movement". According to Ray Strachey, the leader of the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Millicent Fawcett, read the first edition and "thought it so objectionable and mischievous that she tore it up into small pieces". Whereas Maude Royden described it as a "nauseous publication". Edgar Ansell commented that it was "a disgusting publication... indecent, immoral and filthy."

Other feminists were much more supportive, Ada Nield Chew, argued that the was "meat and drink to the sincere student who is out to learn the truth, however unpalatable that truth may be." Benjamin Tucker commented that it was "the most important publication in existence". Floyd Dell, who worked for the Chicago Evening Post argued that before the arrival of The Freewoman: "I had to lie about the feminist movement. I lied loyally and hopefully, but I could not have held out much longer. Your paper proves that feminism has a future as well as a past." Guy Aldred pointed out: "I think your paper deserves to succeed. I will use my influence in the anarchist movement to this end." Others showed their support for the venture by writing without payment for the journal. This included Teresa Billington-Greig, Rebecca West, H. G. Wells, Edward Carpenter, Havelock Ellis, Stella Browne, C. H. Norman, Edmund Haynes, Catherine Gasquoine Hartley, Huntley Carter, Lily Gair Wilkinson and Rose Witcup.

The most controversial aspect of the The Freewoman was its support for free-love. On 23rd November, 1911 Rebecca West wrote an article where she claimed: "Marriage had certain commercial advantages. By it the man secures the exclusive right to the woman's body and by it, the woman binds the man to support her during the rest of her life... a more disgraceful bargain was never struck."

On 28th December 1911, Dora Marsden began a five-part series on morality. Dora argued that in the past women had been encouraged to restrain their senses and passion for life while "dutifully keeping alive and reproducing the species". She criticised the suffrage movement for encouraging the image of "female purity" and the "chaste ideal". Dora suggested that this had to be broken if women were to be free to lead an independent life. She made it clear that she was not demanding sexual promiscuity for "to anyone who has ever got any meaning out of sexual passion the aggravated emphasis which is bestowed upon physical sexual intercourse is more absurd than wicked."

Dora Marsden went on to attack traditional marriage: "Monogamy was always based upon the intellectual apathy and insensitiveness of married women, who fulfilled their own ideal at the expense of the spinster and the prostitute." According to Marsden monogamy's four cornerstones were "men's hypocrisy, the spinster's dumb resignation, the prostitute's unsightly degradation and the married woman's monopoly." Marsden then added "indissoluble monogamy is blunderingly stupid, and reacts immorally, producing deceit, sensuality, vice, promiscuity and an unfair monopoly."

Dora Marsden argued that it would be better if women had a series of monogamous relationships. Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990) has argued: "How far her views were based on her own experience it is difficult to tell. Yet the notion of a passionate but not necessarily sexual relationship would perhaps adequately describe her friendship with Mary Gawthorpe, if not others too. Certainly, her argument would appeal to single women like herself who had sexual desires and feelings but were not allowed to express them - unless, of course, in marriage. Even then, sex, for women at least, was supposed to be reserved for procreation."

Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, the wife of George Bernard Shaw, wrote to Dora Marsden "though there has been much I have not agreed with in the paper", The Freewoman was nevertheless a "valuable medium of self-expression for a clever set of young men and women". However, Olive Schreiner disagreed and argued that the debates about sexuality were inappropriate and revolting in a publication of "the women's movement". Frank Watts wrote a letter to the journal that if women really wanted to discuss sex "then it must be admitted by sane observers that man in the past was exercising a sure instinct in keeping his spouse and girl children within the sheltered walls of ignorance."

By the summer of 1912 Dora Marsden had become disillusioned with the parliamentary system and no longer considered it important to demand women's suffrage: "The politics of the community are a mere superstructure, built upon the economic base... even though Mr. George Lansbury were Prime Minister and every seat in the House occupied by Socialist deputies, the capitalist system being what it is they would be powerless to effect anything more than the slow paced reform of which the sole aim is to make men and masters settle down in a comfortable but unholy alliance... the capitalists own the states. A handful of private capitalists could make England, or any other country, bankrupt within a week."

This article brought a rebuke from H. G. Wells: That you do not know what you want in economic and social organization, that the wild cry for freedom which makes me so sympathetic with your paper, and which echoes through every column of it, is unsupported by the ghost of a shadow of an idea how to secure freedom. What is the good of writing that economic arrangements will have to be adjusted to the Soul of Man if you are not prepared with anything remotely resembling a suggestion of how the adjustment is to be affected?"

Mary Gawthorpe also criticised Dora Marsden for her what she called her "philosophical anarchism". She told her that she "was not really an anarchist at all" but one who believed in rank, with herself at the top. Mary added: "Intellectually you have signed on as a member of the coming aristocracy. Free individuals you would have us be, but you would have us in our ranks... I watch you from week to week governing your paper. You have your subordinates. You say to one go and she goes, to another come, and she comes."

During this period Dora Marsden developed loving relationships with several women, including Mary Gawthorpe, Rona Robinson, Grace Jardine and Harriet Shaw Weaver. In her letters to these women she often referred to them as "sweetheart". Her biographer, Les Garner, has argued: "Whether any of her friendships with women were sexual cannot be determined - certainly they were close and certainly too, Dora's personality and fragile beauty inspired many endearing comments from her friends. She appeared to have a special and unique quality that inspired devotion, if not awe, in some women.... Whether Dora was gay in the modern sense is unknown. There is no concrete evidence to support such a claim."

In March 1912, Mary Gawthorpe was unable to continue working as co-editor of The Freewoman. Marsden wrote in the journal that "we earnestly hope that the coming months will see her restored to health". Although Mary was ill, she had not resigned on health grounds, but because of what she claimed was "Dora's bullying" and her "philosophical anarchism". Gawthorpe returned all Dora's letters and asked her not to write again: "The sight of your letters I am obliged to confess turns me white with emotion and I have acute heart attacks following on from that."

Mary Gawthorpe's health gradually recovered and in 1916 she emigrated to the United States. She soon became active in the National Woman's Suffrage Party in New York City. After American women won the vote, Mary became involved in the trade union movement and in 1920 became a full-time official of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union.

On 19th July 1921 Mary married John Sanders and became an American citizen. As Sandra Stanley Holton has pointed out: "Throughout her life she retained her single name. She made a brief return to Britain in 1933, and was also in contact with the Suffragette Fellowship in these years. Little is known of her life after this date, though some of her surviving correspondence from the 1950s and 1960s shows that she remained keenly interested in political issues, and was still in touch with movements in Britain, including the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament."

In 1962 Mary Gawthorpe published Up Hill to Holloway, the story of her life up to her release from prison in November 1906. She died at her home in Long Island on 12th March 1973.

On this day in 2003 Howard Fast died in Old Greenwich, Connecticut. Fast, the son of a factory worker, was born in New York City on 11th November, 1914. Fast became a socialist after reading The Iron Heel, a novel written by Jack London. "The Iron Heel was my first real contact with socialism; the book... had a tremendous effect on me. London anticipated fascism as no other writer of the time did."

He dropped out of high school and at the age of 18 published his first novel Two Villages. Fast held strong left-wing views and a large number of his novels dealt with political themes. This included a series of three books on the American Revolutionary War period: Conceived in Liberty (1939), The Unvanquished (1942), and Citizen Tom Paine (1943).

In 1943 Fast joined the American Communist Party. As he later recalled: "In the party I found ambition, narrowness and hatred; I also found love and dedication and high courage and integrity — and some of the noblest human beings I have ever known." His Marxist views were reflected in the novels that he wrote during this period. This included Freedom Road (1944), a novel that dealt with the Reconstruction era; The American (1946) and a fictionalized biography of the radical Illinois governor, John Peter Altgeld.

On the morning of 20th July, 1948, Eugene Dennis, the general secretary and eleven other party leaders, including John Gates, William Z. Foster, Benjamin Davis, Robert G. Thompson, Gus Hall, Benjamin Davis, Henry M. Winston, and Gil Green were arrested and charged under the Alien Registration Act. This law, passed by Congress in 1940, made it illegal for anyone in the United States "to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government".

The trial began on 17th January, 1949. As John Gates pointed out: "There were eleven defendants, the twelfth, Foster, having been severed from the case because of his serious, chronic heart ailment." After a nine month trial the leaders of the American Communist Party were found guilty of violating the Alien Registration Act and sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. Robert G. Thompson, because of his war record, received only three years.

In his autobiography, Being Red, Fast commented: "That the jury made a mockery of the months of evidence and came to its verdict of guilty almost instantly tells more about the nature of this trial than a hundred pages of legal evidence. What fell to us - and by us, I mean those of us in the arts - was the question of what we could do in the new conditions of anti-Communist propaganda created by the trial. It was not only the twelve defendants in Foley Square who were under attack; in every trade union where the Communist Party had any influence, Communists and suspected Communists were being attacked and driven from their leadership positions, from the union, and from their jobs. In this, the anti-Communists (many of them in their jobs because of the work and courage of the Communist organizers) in the AFL and the CIO turned and led the hunt against the Communists."

In 1950 Fast was ordered to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. because he had contributed to the support of a hospital for Popular Front forces in Toulouse during the Spanish Civil War. When he appeared before the HUAC he efused to name fellow members of American Communist Party, claiming that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The HUAC and the courts during appeals disagreed and he was sentenced to three months in prison.

On his release from prison Fast discovered that Jerome had arranged the production of The Hammer. "During the weeks before going to prison, I had written a play called The Hammer. It was a drama about a Jewish family during the war years, a hard-working father who keeps his head just above water, and his three sons. One son comes out of the army, badly wounded, badly scarred. Another son makes a fortune out of the war, and the youngest son provides his share of the drama by deciding to enlist."

Howard Fast went to see the pre-view of the play: "The play began. The father came onstage, Michael Lewin, small, slender, pale white skin, and orange hair. Nina Normani, playing Michael's wife, small, pale. The first son came onstage, James Earl Jones, six feet and two inches, barrel-cheated, eighteen years old if my memory serves me, two hundred pounds of bone and muscle if an ounce, and a bass voice that shook the walls of the little theater."

Fast complained about the casting of James Earl Jones as Jimmy Jones. He was told that it had all been arranged by Victor Jerome and that he was being a white chauvinist in objecting to the part played by a black actor. Fast replied: "I'm not being a white chauvinist, Lionel. But Mike here weighs in at maybe a hundred and ten pounds, and he's as pale as anyone can be and he's Jewish, and for God's sake, tell me what genetic miracle could produce Jimmy Jones." However, after threats that Jerome would have him expelled from the Communist Party he accepted the casting. (28)

In 1950 Howard Fast attempted to get his novel about, Spartacus, an account of the 71 B.C. slave revolt, published. Eight major publishers rejected it. Alfred Knopf sent the manuscript back unopened, saying he wouldn't even look at the work of a traitor. Fast now realised he was blacklisted and formed his own company, the Blue Heron Press, to publish Spartacus (1951). He continued write and publish books that reflected his left-wing views. This included Silas Timberman (1954), a novel about a victim of McCarthyism and The Story of Lola Gregg (1956), describing the FBI pursuit and capture of a communist trade unionist. Fast also worked as a staff writer for the Daily Worker.

According to John Gates, Fast was having serious doubts about communism. He suggested that Eugene Dennis should talk to Fast: "I told Dennis and other party leaders of Fast's deep personal crisis and implored them to talk to him, but outside of some of us on the Daily Worker, not a single party leader thought it important enough to talk to the one writer of national, even world-wide, reputation still in the party."

During the 20th Soviet Communist Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Joseph Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. Howard Fast explained how he reacted in The Daily Worker to the speech: "We accused the Soviets. We demanded explanations. For the first time in the life of the Communist Party of the United States, we challenged the Russians for the truth, we challenged the disgraceful executions that had taken place in Czechoslovakia and Hungary. We demanded explanations and openness. John Gates pulled no punches, printed the hundreds of letters that poured in from our readers, the bitterness of those who had given the best and most fruitful years of their lives to an organization that still clung to the tail of the Soviet Union."

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprisingan estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar.

John Gates, the editor of the Daily Worker, was highly critical of the actions of Nikita Khrushchev and stated that "for the first time in all my years in the Party I felt ashamed of the name Communist". He then went on to add that "there was more liberty under Franco's fascism than there is in any communist country." As a result he was accused of being "right-winger, Social-Democrat, reformist, Browderite, peoples' capitalist, Trotskyist, Titoite, Stracheyite, revisionist, anti-Leninist, anti-party element, liquidationist, white chauvinist, national Communist, American exceptionalist, Lovestoneite, Bernsteinist".

William Z. Foster was a loyal supporter of the leadership of the Soviet Union and refused to condemn the regime's record on human rights. Foster failed to criticize the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution. Large numbers left the party. At the end of the Second World War it had 75,000 members. By 1957 membership had dropped to 5,000. In 1957 Fast published The Naked God: The Writer and the Communist Party (1957).

On 22nd December, 1957, the American Communist Party Executive Committee decided to close down the Daily Worker. John Gates argued: "Throughout the 34 years of its existence, the Daily Worker has withstood the attacks of Big Business, the McCarthyites and other reactionaries. It has taken a drive from within the party - conceived in blind factionalism and dogmatism - to do what our foes have never been able to accomplish. The party leadership must once and for all repudiate the Foster thesis, defend the paper and its political line, and seek to unite the entire party behind the paper."

Howard Fast, who was a staff journalist on the Daily Worker added: "The Daily Worker published its last issue on January 13, 1958, precisely thirty-four years after its first issue had appeared. I doubt whether there was a day during those decades when the paper was not in debt. It was always understaffed, and its staff was always underpaid. It never compromised with the truth as it saw the truth; and while it was at times rigid and believing of whatever the Soviet Union put forth, it was so only because of its blind faith in the socialist cause. It is a part of the history of this country, and like the party that supported it, it preached love for its native land. It had once boasted a daily circulation of close to 100,000. Its final run was five thousand copies."

The Hollywood Blacklist was ended in 1960 when Dalton Trumbo wrote the screenplay for the film Spartacus based on Fast's novel of the same name. Fast himself moved to Hollywood where he wrote several screenplays. However, he continued to write political novels and had considerable commercial success with The Immigrants (1977), Second Generation (1978), The Establishment (1979), The Outsider (1984) and the Immigrant's Daughter (1985). His autobiography, Being Red, was published in 1990.

During his lifetime he published more than 40 novels under his own name and 20 as E.V. Cunningham. Fast also wrote a biography of Josip Tito. His books were translated into 82 different languages and his last novel, Greenwich, was published in 2000. As Alan Wald has pointed out: "In the 1940s, and again in the 1970s and 1980s, he achieved best-seller status with novels explicity promoting left-wing ideas."

In 1950 Fast was ordered to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. because he had contributed to the support of a hospital for Popular Front forces in Toulouse during the Spanish Civil War. When he appeared before the HUAC he efused to name fellow members of American Communist Party, claiming that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The HUAC and the courts during appeals disagreed and he was sentenced to three months in prison.

On his release from prison Fast discovered that Jerome had arranged the production of The Hammer. "During the weeks before going to prison, I had written a play called The Hammer. It was a drama about a Jewish family during the war years, a hard-working father who keeps his head just above water, and his three sons. One son comes out of the army, badly wounded, badly scarred. Another son makes a fortune out of the war, and the youngest son provides his share of the drama by deciding to enlist."

Fast went to see the pre-view of the play: "The play began. The father came onstage, Michael Lewin, small, slender, pale white skin, and orange hair. Nina Normani, playing Michael's wife, small, pale. The first son came onstage, James Earl Jones, six feet and two inches, barrel-cheated, eighteen years old if my memory serves me, two hundred pounds of bone and muscle if an ounce, and a bass voice that shook the walls of the little theater."

Fast complained about the casting of James Earl Jones as Jimmy Jones. He was told that it had all been arranged by Victor Jerome and that he was being a white chauvinist in objecting to the part played by a black actor. Fast replied: "I'm not being a white chauvinist, Lionel. But Mike here weighs in at maybe a hundred and ten pounds, and he's as pale as anyone can be and he's Jewish, and for God's sake, tell me what genetic miracle could produce Jimmy Jones." However, after threats that Jerome would have him expelled from the Communist Party he accepted the casting. (28)

In 1950 Howard Fast attempted to get his novel about, Spartacus, an account of the 71 B.C. slave revolt, published. Eight major publishers rejected it. Alfred Knopf sent the manuscript back unopened, saying he wouldn't even look at the work of a traitor. Fast now realised he was blacklisted and formed his own company, the Blue Heron Press, to publish Spartacus (1951). He continued write and publish books that reflected his left-wing views. This included Silas Timberman (1954), a novel about a victim of McCarthyism and The Story of Lola Gregg (1956), describing the FBI pursuit and capture of a communist trade unionist. Fast also worked as a staff writer for the Daily Worker.

According to John Gates, Fast was having serious doubts about communism. He suggested that Eugene Dennis should talk to Fast: "I told Dennis and other party leaders of Fast's deep personal crisis and implored them to talk to him, but outside of some of us on the Daily Worker, not a single party leader thought it important enough to talk to the one writer of national, even world-wide, reputation still in the party."

During the 20th Soviet Communist Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Joseph Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. Howard Fast explained how he reacted in The Daily Worker to the speech: "We accused the Soviets. We demanded explanations. For the first time in the life of the Communist Party of the United States, we challenged the Russians for the truth, we challenged the disgraceful executions that had taken place in Czechoslovakia and Hungary. We demanded explanations and openness. John Gates pulled no punches, printed the hundreds of letters that poured in from our readers, the bitterness of those who had given the best and most fruitful years of their lives to an organization that still clung to the tail of the Soviet Union."

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprisingan estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar.

John Gates, the editor of the Daily Worker, was highly critical of the actions of Nikita Khrushchev and stated that "for the first time in all my years in the Party I felt ashamed of the name Communist". He then went on to add that "there was more liberty under Franco's fascism than there is in any communist country." As a result he was accused of being "right-winger, Social-Democrat, reformist, Browderite, peoples' capitalist, Trotskyist, Titoite, Stracheyite, revisionist, anti-Leninist, anti-party element, liquidationist, white chauvinist, national Communist, American exceptionalist, Lovestoneite, Bernsteinist".

William Z. Foster was a loyal supporter of the leadership of the Soviet Union and refused to condemn the regime's record on human rights. Foster failed to criticize the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution. Large numbers left the party. At the end of the Second World War it had 75,000 members. By 1957 membership had dropped to 5,000. In 1957 Fast published The Naked God: The Writer and the Communist Party (1957).

On 22nd December, 1957, the American Communist Party Executive Committee decided to close down the Daily Worker. John Gates argued: "Throughout the 34 years of its existence, the Daily Worker has withstood the attacks of Big Business, the McCarthyites and other reactionaries. It has taken a drive from within the party - conceived in blind factionalism and dogmatism - to do what our foes have never been able to accomplish. The party leadership must once and for all repudiate the Foster thesis, defend the paper and its political line, and seek to unite the entire party behind the paper."

Howard Fast, who was a staff journalist on the Daily Worker added: "The Daily Worker published its last issue on January 13, 1958, precisely thirty-four years after its first issue had appeared. I doubt whether there was a day during those decades when the paper was not in debt. It was always understaffed, and its staff was always underpaid. It never compromised with the truth as it saw the truth; and while it was at times rigid and believing of whatever the Soviet Union put forth, it was so only because of its blind faith in the socialist cause. It is a part of the history of this country, and like the party that supported it, it preached love for its native land. It had once boasted a daily circulation of close to 100,000. Its final run was five thousand copies."

The Hollywood Blacklist was ended in 1960 when Dalton Trumbo wrote the screenplay for the film Spartacus based on Fast's novel of the same name. Fast himself moved to Hollywood where he wrote several screenplays. However, he continued to write political novels and had considerable commercial success with The Immigrants (1977), Second Generation (1978), The Establishment (1979), The Outsider (1984) and the Immigrant's Daughter (1985). His autobiography, Being Red, was published in 1990.

During his lifetime he published more than 40 novels under his own name and 20 as E.V. Cunningham. Fast also wrote a biography of Josip Tito. His books were translated into 82 different languages and his last novel, Greenwich, was published in 2000. As Alan Wald has pointed out: "In the 1940s, and again in the 1970s and 1980s, he achieved best-seller status with novels explicity promoting left-wing ideas."

Un-American Activities Committee in 1950.