Howard Fast

Howard Fast, the son of a factory worker, was born in New York City on 11th November, 1914. Fast became a socialist after reading The Iron Heel, a novel written by Jack London. "The Iron Heel was my first real contact with socialism; the book... had a tremendous effect on me. London anticipated fascism as no other writer of the time did."

He dropped out of high school and at the age of 18 published his first novel Two Villages. Fast held strong left-wing views and a large number of his novels dealt with political themes. This included a series of three books on the American Revolutionary War period: Conceived in Liberty (1939), The Unvanquished (1942), and Citizen Tom Paine (1943).

In 1943 Fast joined the American Communist Party. As he later recalled: "In the party I found ambition, narrowness and hatred; I also found love and dedication and high courage and integrity — and some of the noblest human beings I have ever known." His Marxist views were reflected in the novels that he wrote during this period. This included Freedom Road (1944), a novel that dealt with the Reconstruction era; The American (1946) and a fictionalized biography of the radical Illinois governor, John Peter Altgeld.

On the morning of 20th July, 1948, Eugene Dennis, the general secretary and eleven other party leaders, including John Gates, William Z. Foster, Benjamin Davis, Robert G. Thompson, Gus Hall, Benjamin Davis, Henry M. Winston, and Gil Green were arrested and charged under the Alien Registration Act. This law, passed by Congress in 1940, made it illegal for anyone in the United States "to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government".

The trial began on 17th January, 1949. As John Gates pointed out: "There were eleven defendants, the twelfth, Foster, having been severed from the case because of his serious, chronic heart ailment." After a nine month trial the leaders of the American Communist Party were found guilty of violating the Alien Registration Act and sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. Robert G. Thompson, because of his war record, received only three years.

In his autobiography, Being Red, Fast commented: "That the jury made a mockery of the months of evidence and came to its verdict of guilty almost instantly tells more about the nature of this trial than a hundred pages of legal evidence. What fell to us - and by us, I mean those of us in the arts - was the question of what we could do in the new conditions of anti-Communist propaganda created by the trial. It was not only the twelve defendants in Foley Square who were under attack; in every trade union where the Communist Party had any influence, Communists and suspected Communists were being attacked and driven from their leadership positions, from the union, and from their jobs. In this, the anti-Communists (many of them in their jobs because of the work and courage of the Communist organizers) in the AFL and the CIO turned and led the hunt against the Communists."

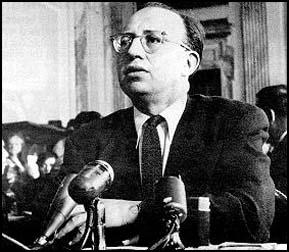

Un-American Activities Committee in 1950.

In 1950 Fast was ordered to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. because he had contributed to the support of a hospital for Popular Front forces in Toulouse during the Spanish Civil War. When he appeared before the HUAC he efused to name fellow members of American Communist Party, claiming that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The HUAC and the courts during appeals disagreed and he was sentenced to three months in prison.

On his release from prison Fast discovered that Jerome had arranged the production of The Hammer. "During the weeks before going to prison, I had written a play called The Hammer. It was a drama about a Jewish family during the war years, a hard-working father who keeps his head just above water, and his three sons. One son comes out of the army, badly wounded, badly scarred. Another son makes a fortune out of the war, and the youngest son provides his share of the drama by deciding to enlist."

Fast went to see the pre-view of the play: "The play began. The father came onstage, Michael Lewin, small, slender, pale white skin, and orange hair. Nina Normani, playing Michael's wife, small, pale. The first son came onstage, James Earl Jones, six feet and two inches, barrel-cheated, eighteen years old if my memory serves me, two hundred pounds of bone and muscle if an ounce, and a bass voice that shook the walls of the little theater."

Fast complained about the casting of James Earl Jones as Jimmy Jones. He was told that it had all been arranged by Victor Jerome and that he was being a white chauvinist in objecting to the part played by a black actor. Fast replied: "I'm not being a white chauvinist, Lionel. But Mike here weighs in at maybe a hundred and ten pounds, and he's as pale as anyone can be and he's Jewish, and for God's sake, tell me what genetic miracle could produce Jimmy Jones." However, after threats that Jerome would have him expelled from the Communist Party he accepted the casting. (28)

In 1950 Howard Fast attempted to get his novel about, Spartacus, an account of the 71 B.C. slave revolt, published. Eight major publishers rejected it. Alfred Knopf sent the manuscript back unopened, saying he wouldn't even look at the work of a traitor. Fast now realised he was blacklisted and formed his own company, the Blue Heron Press, to publish Spartacus (1951). He continued write and publish books that reflected his left-wing views. This included Silas Timberman (1954), a novel about a victim of McCarthyism and The Story of Lola Gregg (1956), describing the FBI pursuit and capture of a communist trade unionist. Fast also worked as a staff writer for the Daily Worker.

According to John Gates, Fast was having serious doubts about communism. He suggested that Eugene Dennis should talk to Fast: "I told Dennis and other party leaders of Fast's deep personal crisis and implored them to talk to him, but outside of some of us on the Daily Worker, not a single party leader thought it important enough to talk to the one writer of national, even world-wide, reputation still in the party."

During the 20th Soviet Communist Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Joseph Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. Howard Fast explained how he reacted in The Daily Worker to the speech: "We accused the Soviets. We demanded explanations. For the first time in the life of the Communist Party of the United States, we challenged the Russians for the truth, we challenged the disgraceful executions that had taken place in Czechoslovakia and Hungary. We demanded explanations and openness. John Gates pulled no punches, printed the hundreds of letters that poured in from our readers, the bitterness of those who had given the best and most fruitful years of their lives to an organization that still clung to the tail of the Soviet Union."

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprisingan estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar.

John Gates, the editor of the Daily Worker, was highly critical of the actions of Nikita Khrushchev and stated that "for the first time in all my years in the Party I felt ashamed of the name Communist". He then went on to add that "there was more liberty under Franco's fascism than there is in any communist country." As a result he was accused of being "right-winger, Social-Democrat, reformist, Browderite, peoples' capitalist, Trotskyist, Titoite, Stracheyite, revisionist, anti-Leninist, anti-party element, liquidationist, white chauvinist, national Communist, American exceptionalist, Lovestoneite, Bernsteinist".

William Z. Foster was a loyal supporter of the leadership of the Soviet Union and refused to condemn the regime's record on human rights. Foster failed to criticize the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution. Large numbers left the party. At the end of the Second World War it had 75,000 members. By 1957 membership had dropped to 5,000. In 1957 Fast published The Naked God: The Writer and the Communist Party (1957).

On 22nd December, 1957, the American Communist Party Executive Committee decided to close down the Daily Worker. John Gates argued: "Throughout the 34 years of its existence, the Daily Worker has withstood the attacks of Big Business, the McCarthyites and other reactionaries. It has taken a drive from within the party - conceived in blind factionalism and dogmatism - to do what our foes have never been able to accomplish. The party leadership must once and for all repudiate the Foster thesis, defend the paper and its political line, and seek to unite the entire party behind the paper."

Howard Fast, who was a staff journalist on the Daily Worker added: "The Daily Worker published its last issue on January 13, 1958, precisely thirty-four years after its first issue had appeared. I doubt whether there was a day during those decades when the paper was not in debt. It was always understaffed, and its staff was always underpaid. It never compromised with the truth as it saw the truth; and while it was at times rigid and believing of whatever the Soviet Union put forth, it was so only because of its blind faith in the socialist cause. It is a part of the history of this country, and like the party that supported it, it preached love for its native land. It had once boasted a daily circulation of close to 100,000. Its final run was five thousand copies."

The Hollywood Blacklist was ended in 1960 when Dalton Trumbo wrote the screenplay for the film Spartacus based on Fast's novel of the same name. Fast himself moved to Hollywood where he wrote several screenplays. However, he continued to write political novels and had considerable commercial success with The Immigrants (1977), Second Generation (1978), The Establishment (1979), The Outsider (1984) and the Immigrant's Daughter (1985). His autobiography, Being Red, was published in 1990.

During his lifetime he published more than 40 novels under his own name and 20 as E.V. Cunningham. Fast also wrote a biography of Josip Tito. His books were translated into 82 different languages and his last novel, Greenwich, was published in 2000. As Alan Wald has pointed out: "In the 1940s, and again in the 1970s and 1980s, he achieved best-seller status with novels explicity promoting left-wing ideas."

Howard Fast died in Old Greenwich, Connecticut, on 12th March, 2003.

Primary Sources

(1) Howard Fast, Being Red (1990)

We were always poor, but while my mother lived, we children never realized that we were poor. My father, at the age of fourteen, was an iron worker in the open-shed furnaces on the East River below Fourteenth Street. There the wrought iron that festooned the city was hammered into shape at open forges. As a kid, Barney had run beer for the big, heavy-muscled men who hammered out the iron at the blazing forges, and there was nothing else he wanted to do. But the iron sheds disappeared as fashions in building changed, and Barney went to work as a gripper man on one of the last cable cars in the city. From there to the tin factory, and finally to being a cutter in a dress factory. He never earned more than forty dollars a week during my mother's lifetime, yet with this forty dollars my mother made do. She was a wise woman, and if a wretched tenement was less than her dream of America, she would not surrender. She scrubbed and sewed and knitted. She made all the clothes for all of her children, cutting little suits out of velvet and fine wools and silks; she cooked and cleaned with a vengeance, and to me she seemedi-a sort of princess, with her stories of London and Kew and Kensington Gardens and the excitement and tumult of Petticoat Lane and Covent Garden. Memories of this beautiful lady, whose speech was so different from the speech of the others around me, were wiped out at the moment of her death.

(2) CNN News (13th March, 2003)

In the 1940s, "Citizen Tom Paine" and "The American," a fictionalized biography of Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld, became best sellers - but brought him trouble from the House Un-American Activities Committee, which labeled them as Communist propaganda. "Citizen Tom Paine" was banned in high school libraries in New York City.

In 1945, the committee demanded he identify people who helped build a hospital in France for anti-fascist fighters. Fast refused and after years of legal battles was jailed for contempt.

Prison only made him more radical, as Fast "began more deeply than ever before to comprehend the full agony and hopelessness of the underclass," he later recalled. Out of this experience he wrote "Spartacus," his populist version of the slave revolt in ancient Rome.

The novel was rejected by several publishers, many of whom received visits from FBI agents, and Fast eventually released it himself.

(3) Eric Homberger, The Guardian (14th March, 2003)

He seldom wrote autobiographically; the nearest he came to a self-portrait was in Citizen Tom Paine. For Paine, the greatest revolutionary propagandist of the 18th century, the likely fate of the American revolution of 1776, as well as of the French of 1789, was betrayal and defeat. Paine knew the vicious attacks of enemies in America and abandonment by his friends, as well as persecution and imprisonment in France under the Jacobins.

And, indeed, Fast's novel is a portrait of the writer as revolutionary. It is also a singularly harsh portrayal of the nature of revolution itself, and of the terrible fate awaiting its creators; it belongs on the same shelf as Arthur Koestler's novel of the fate of an old Bolshevik, Darkness At Noon (1940).

It was while writing Citizen Tom Paine that Fast joined the Communist party. The wartime love affair with the Soviet Union and the Red army was at its peak. Fast later showed himself to be an insightful diagnostician of the way good people, worthy of affection and respect, were degraded, humiliated, lied to and betrayed by Stalin and his conscienceless henchmen in the American party.

The title for his 1957 study, The Naked God: The Writer And Communism, was drawn from a brief, brilliant passage reflecting on the East German Stalinist leader Walther Ulbricht: "He has lost touch with humankind. For him are no more hopes or visions or high dreams - only the caress of power over his righteousness."

(4) Howard Fast, Being Red (1990)

That the jury made a mockery of the months of evidence and came to its verdict of guilty almost instantly tells more about the nature of this trial than a hundred pages of legal evidence. What fell to us - and by us, I mean those of us in the arts - was the question of what we could do in the new conditions of anti-Communist propaganda created by the trial. It was not only the twelve defendants in Foley Square who were under attack; in every trade union where the Communist Party had any influence, Communists and suspected Communists were being attacked and driven from their leadership positions, from the union, and from their jobs. In this, the anti-Communists (many of them in their jobs because of the work and courage of the Communist organizers) in the AFL and the CIO turned and led the hunt against the Communists.

Where did that leave us? I had an idea that I put to some of the leaders, but they brushed it aside. The party had no time or money for what they certainly regarded as the high jinks of the intellectuals, a group never too highly regarded by any Communist leaders at that time. My idea was to organize a great meeting of the arts in the cause of peace. My feeling was that the struggle for peace was paramount. If the march to war could be halted, other matters could be solved more easily. I laid out the details of what could be done to Lionel Berman of the Cultural Section, and he agreed with me that it was worth a try. The leadership of the party turned us down flat. They felt that every resource had to be directed toward fighting the repression and winning the trial. They had little faith in what we might do, and they had no money to spare for us.

(5) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

One of those most shaken was Howard Fast, the only literary figure of note left in the Communist Party. He was a controversial figure not only in the country generally but in the party too. A fabulously successful author before becoming known as a Communist, he had been boycotted for his political beliefs. In the Communist movement he was both idolized and cordially disliked. His forte was the popular historical novel, although he was not noted for his depth of characterization or historical scholarship. Fast had made money but he had also lost it because of his adherence to his principles, and he had gone to jail for his beliefs. Fast had stuck out his neck more than most; he had received the Stalin Prize and defended everything Communist and attacked everything capitalist in the most extravagant terms. It was to be expected that he would react to the Khrushchev revelations in a highly emotional manner, and I know of no one who went through a greater moral anguish and torture.

I told Dennis and other party leaders of Fast's deep personal crisis and implored them to talk to him, but outside of some of us on the Daily Worker, not a single party leader thought it important enough to talk to the one writer of national, even world-wide, reputation still in the party. Later when he announced his withdrawal and told his story, party leaders leaped on him like a pack of wolves and began that particular brand of character assassination which the Communist movement has always reserved for defectors from its ranks.

Fast's book, The Naked God, contains considerable truth, tut it suffers from his weakness of portraying people as either good guys or bad guys. I am far from the angel he depicts and the others are not quite the devils he makes them out. The reality is more subtle, complex and contradictory. But the Daily Worker, to its credit, never joined in the torrent of abuse from the Left that was heaped on Fast. His reaction to his Communist experience has been highly charged with emotion, but not without cause. At the very least, as a man who had given his whole life and career to communism, Fast deserves more understanding and compassion from the Left.

(6) Howard Fast, Being Red (1990)

The offices (of the American Communist Party) were in a nine-story building between University Place and Broadway, a building that also housed The Daily Worker and the Communist Party leadership. The people in the top offices of the party, the general secretary and the members of the National Committee, were housed on the ninth floor, and in referring to them, one often spoke simply of "the ninth floor." The general secretary of the party at that time, Gene Dennis, was a tall, handsome man who had taken over the party leadership from Earl Browder. In 1944, Browder, the leader of the party through some of its most bitter struggles during the thirties, had attempted to change the party from a political party that offered candidates in elections to a sort of educational Marxist entity. His move, I believe, was based on the wartime and prewar influence of the party on Roosevelt's New Deal, and on the hope that it might continue. It is impossible here to go into the lengthy and frequently obtuse theoretical discussion on this point; much of it was almost as meaningless then as it would be today. Sufficient to say that Browder lost the struggle, was removed from leadership, and expelled from the party. Dennis was his successor.

I had never met Gene Dennis and I had never ventured to the sacrosanct heights of the ninth floor, and being in proper awe of the leaders of an organization I had come to respect and honor, I went first to Joe North in the more familiar offices of The New Masses. Would he set up a meeting for me with Gene Dennis? I had perhaps an exaggerated sense of the importance of carrying a message from the Communist Party of Northern India to the Communist Party of the United States, yet in all reality, a plea from one Communist Party to another was of importance and to be treated with respect. Joe agreed with me, picked up his phone, and was told that Dennis would see me. I took the elevator up to the ninth floor, was shown into Dennis's office. He sat behind his desk; he did not rise nor did he offer his hand. Nor did he smile. Nor did he ask me to sit down. Nor did he indicate that he was either pleased or displeased to meet me.

Now this is the national leader of the Communist Party of the United States. Here I am, one of the leading and - at that time - most honored writers in the country. The party busted its ass to get me into the movement. It showered me with praise, lured me with happiness was enough, and I took myself down to the offices of The New Masses on East Twelfth Street. its most winning people, reprinted stuff from my books in The New Masses, and embraced me. But Dennis never asked me to meet him, and now that I was in his office, he looked at me as a judge might look at a prisoner before passing sentence.

Since he didn't ask why I was there, I delivered my message uninvited. Very briefly, I spoke of the crisis in India, and then I repeated to him what the Indian Communist leader had said. He listened, and then he nodded - a signal for me to go.

Am I crazy? I asked myself. Or is this some kind of joke? But Dennis was the last man on earth to exhibit humor. Wasn't he going to ask me what I had seen? Wasn't he going to ask me about the political situation? I had spoken about the largest colonial country in the world. Wasn't he interested? I waited. He told me I could go. I turned and left.

I then went from Dennis's office to Joe North and told him about Dennis's reaction to me and my message from India. Joe said that such was Dennis, and that Dennis was Dennis, and that he was not easy with people. It seemed to me that what a party leader dealt with most was people, and how the devil did he come to be the general secretary of the Communist Party? Joe admitted that Dennis was not the greatest, that it should have been Bill Foster, the grand old man of the left, but Foster had a bad heart and was too old.

(7) New York Times (1st February, 1957)

Howard Fast said yesterday that he had disassociated himself from the American Communist party and no longer considered himself a Communist.

Mr. Fast, the winner of a Stalin International Peace Prize in 1953, has generally been considered the leading Communist writer in this country. His books were once sold in large numbers here, and in recent years many of them have been widely translated and sold throughout the world, particularly in the Soviet Union and other Communist countries. Until last June he was a columnist for The Daily Worker.

Apparently troubled by the need to end his political affiliation, Mr. Fast at first was reluctant to be interviewed. When he agreed, he defined his position in these terms: "I am neither anti-Soviet nor anti-Communist, but I cannot work and write in the Communist movement."

Nikita S. Khrushchev's secret speech last year exposing Stalin was the chief factor leading to his present position, Mr. Fast said.

"It was incredible and unbelievable to me," he said, "that Khrushchev did not end his speech with a promise of the reforms needed to guarantee that Stalin's crimes will not be repeated, reforms such as an end to capital punishment, trial by jury and habeas corpus. Without these reforms one can make neither sense nor reason of the speech itself."

In a column in The Daily Worker last June (Man's Hope, June 12, 1956), Mr. Fast first indicated the shock and anger that the Khrushchev speech had produced in him. He ceased to contribute to that newspaper after that, but did not then break with the Communist movement.

Mr. Fast indicated he had spent the months since last June in fighting out with himself the question of his future. He asserted that he admired Communist party members as dedicated fighters for peace, but that he personally felt he could no longer submit to Communist discipline.

Revelations of anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union also influenced his decision. "I knew little about anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union before the Khrushchev speech," Mr. Fast said. "That little troubled me, but I repressed my doubts. Then the article appeared in The Folksshtime last spring telling what had actually happened. It was not an easy thing to live with."

The Folksshtime, a Yiddish language Communist newspaper in Poland, printed the first news from a Communist source of the repression of Yiddish culture in the Soviet Union and of the jailing and execution of numerous Yiddish writers in that country under Stalin.

Asserting that he had been a devoted Communist because of his belief in democracy, equalitarianism and social justice, Mr. Fast said that his anger at the Khrushchev speech was particularly sharp because of his experience with the American judicial system.

"I was tried and convicted in 1946 under circumstances that made a mockery of our pretensions of justice here," he said. "But while that was happening, I was consoled by the belief that in the Soviet Union a person would receive justice. I can no longer believe this."

Mr. Fast was convicted in 1946 on a charge of contempt of Congress arising from his refusal to produce the records of the Joint Antifascist Refugee Committee before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He served three months in jail on the charge.

Recent events in Poland have moved him deeply, Mr. Fast said. "Poland has been a living proof of the dream of many people that socialism and democracy can exist together."

Mr. Fast said he would not repudiate or return the Stalin International Peace Prize he received in 1953.

A Communist sympathizer since the early Nineteen Thirties and a Communist party member for almost a decade and a half, Mr. Fast declared: "I am not ashamed of anything I have done. I fought against war, Negro oppression and social injustice. I am proud of my books. I regret that in some of my political articles I went overboard - but by and large I stand by what I wrote."

Mr. Fast said that in Daily Worker articles written last spring, he had called for Communists to take a new look at the Soviet campaign against cosmopolitanism ( Cosmopolitanism, April 26, 1956), a movement he now regards as a form of Soviet anti-Semitism directed against Jewish intellectuals there, as well as at the party ban on psychoanalysis (Freud and Science, May 1, 1956) and its condemnation of writers like James T. Farrell, author of the Studs Lonigan books and other works of fiction.

"I was supported in raising these questions by John Gates, Alan Max and Joe Clark," Mr. Fast said. Mr. Gates is the editor of The Daily Worker, Mr. Max the managing editor, and Mr. Clark the foreign editor. These three are generally regarded as leaders of the Communist party's "anti-Stalinist" wing.

Tall, dark and thin, Mr. Fast explained his original interest in communism as born of the poverty in which he grew up after his birth here on Nov. 11, 1914.

Mr. Fast estimated that more than 20,000,000 copies of his books had been printed and distributed throughout the world.

(8) New York Times (13th March, 2003)

Mr. Fast's fiction was always didactic to a degree, opposed to modernism, engaged in social struggle and insistent on taking sides and teaching lessons of life's moral significance, and he liked it that way.

"Since I believe that a person's philosophical point of view has little meaning if it is not matched by being and action, I found myself willingly wed to an endless series of unpopular causes, experiences which I feel enriched my writing as much as they depleted other aspects of my life," he said in a 1972 interview.

Despite the international popularity of historical novels like "Paine," which glorified the professional revolutionary, and the huge commercial success that Mr. Fast's well-paced narratives achieved, his work tended to succeed or fail as art to the extent that he distanced himself from ideology.

(9) The Washington Post (13th March, 2003)

Many of his books from the 1940s and 1950s explored class and race disparity in the United States and implicitly promoted what he then considered a utopian Soviet system. In the 1950s, he was one of the most high-profile authors in the United States to be jailed and blacklisted for actions related to membership in the Communist Party.

He wrote of joining the Communist Party in 1943, influenced by "a series of dismal and underpaid jobs that I had held since, at the age of eleven, pressed by the need of our utter poverty, I went to work as a newspaper delivery boy."

He continued: "If we are to seek for understanding, any sort of understanding, then the reader must not only recall the 1930s, but must comprehend the full meaning of the surrender of childhood, a situation that poverty still imposes on millions of children the world over."