On this day on 12th August

On this day in 1851 Isaac Singer is granted a patent for his sewing machine. In 1850 Singer was asked to repair a Lerow & Blodgett sewing machine. For over 20 years efforts had been made to invent an effective sewing machine. A French tailor, Barthélemy Thimonnier, was the first to put a sewing device into commercial operation in an attempt to mechanize embroidery. He patented his device in 1830 and by 1841 he had a factory with eighty machines. However, a mob of tailors, worried about their livelihood, broke in and destroyed them.

The first American to make a significant contribution was Walter Hunt, who developed a machine around 1832 that made a lock stitch. Hunt, who had invented the safety pin and the breech-loading rifle, came from a strong Quaker family, abandoned work on the machine after his daughter told him it would throw seamstresses out of work. For example, in New York City at this time, ten thousand women earned their living through needlework. Elias Howe, a machinist from Cambridge, Massachusetts, was granted a patent on a sewing machine in 1846, but found it difficult finding investors to develop the machine as it was expensive to produce and factory owners felt they could get more from seamstresses for the same money.

Sherburne C. Blodgett, a tailor, joined forces with John Alexander Lerow, to produce a "Rotary Sewing Machine", that was patented in 1849. However, it did not work well and was constantly breaking down. After examining the Lerow & Blodgett sewing machine Isaac Merritt Singer came to the conclusion that it would be more reliable if the shuttle moved in a straight line rather than a circle, with a straight rather than a curved needle. The following year he patented his own sewing machine. It could sew 900 stitches per minute, far better than the 40 of a skilled seamstress.

In 1851 Singer joined forces with Edward Cabot Clark to form the Singer Sewing Machine Company. The Singer was the first practical sewing machine for general domestic use and incorporated the basic eye-pointed needle and lock stitch developed by Elias Howe. The Singer met the demand of the tailoring, and leather industries for a heavier and more powerful machine.

The Singer sewing machine was not an immediate success and sales were poor. For example: 1853 (810), 1854 (879), 1855 (883). In 1856 Singer brought out his first machine intended exclusively for use in the home. These machines sold for $100 each ($2,514.00). Selling these machines was a major problem as the average family income was less than $500 a year.

Singer's partner, Edward Clark, came up with what became known as the Hire Purchase Plan: "By advancing a certain percentage of the total price of the machine, a customer could hire a sewing machine, make monthly payments to it, and eventually own it." Singer only charged $5 for the initial payment, but as soon as they failed to make the monthly payments, the machine was repossessed. This method of selling goods was a great success and sales soared. In 1858 the company had sold 3,594 machines, by 1861 sales were over 16,000.

As a result, individuals with even small incomes could own a Singer sewing machine. As sales grew Singer could bring in mass production techniques. He was now able to cut the price in half, while at the same time increasing his profit margin by 530%. Eventually, the price came down to $30 ($716 in today's money). By 1876 Singer sold 262, 316 machines, more than twice as many as its nearest rival.

In 1882 Isaac Singer expanded into the European market, establishing a factory in Clydebank, near Glasgow. A Canadian plant was opened in Montreal five years later. Others followed; despite great growth in domestic business, the company was soon selling more sewing machines abroad than in the United States. It has been argued that Singer had created America's first multinational corporation.

On this day in 1842 the Plug Riots begin. On the 4th May, 1842, Thomas Duncombe presented to Parliament a Chartist petition signed by 3,250,000 people. As well as demanding the six points of the Charter the document also complained about the "cruel wars against liberty"; and "unconstitutional police force"; the 1834 Poor Law; factory conditions and church taxes on Nonconfotmists. It also included an attack on Queen Victoria, contrasting her income of "£164 17s. 10d. a day" with that of "the producing millions". The Chartists were furious when the House of Commons rejected the petition by 287 votes to 47.

This decision was followed by a series of strikes in the industrial districts. It started in the Midland coalfield, and spread during August to Scotland and to the textile industry in Lancashire and Yorkshire. In some cases, striking workers stopped production by removed the boiler plugs from the steam engines in their factories. As a result, these industrial disputes became known as the Plug Plot.

Some workers argued that they would remain out on strike until the People's Charter became the law of the land. A conference of trade union leaders in Manchester also passed a resolution linking the strikes to the demands for universal suffrage. The strikes were supported by George Julian Harney and Thomas Cooper who had earlier advocated a withdrawel of labour, the Sacred Month, as a strategy to obtain the vote. Feargus O'Connor, the leader of the Physical Force Chartists, who had argued against previous plans for a Sacred Month, denounced the strikes in his Northern Star and even suggested they were being organised by the Anti-Corn League.

The prime minister, Sir Robert Peel favoured a non-intervention approach to the problem, but the Duke of Wellington argued for troops to be sent in to deal with the strikers. Eventually Peel agreed with Wellington and Sir James Graham, the Home Secretary, and the army were dispatched to the trouble areas. Leaders of the strikes, including the members of the Manchester Conference who had voted for linking the dispute with the Chartist demands, were arrested. Several Chartist leaders such as Feargus O'Connor, George Julian Harney and Thomas Cooper were detained. Out of the fifteen hundred people arrested, seventy-nine were found guilty and sentenced to between seven and twenty-one years' transportation. By the end of August rioting had come to an end. Most strikers returned to work but the cotton operatives of Lancashire and the Staffordshire miners held out for another month.

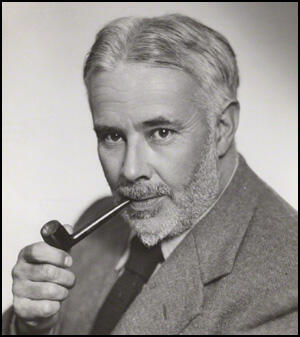

On this day in 1891 English philosopher Cyril Edwin Mitchinson Joad, the son of Edwin Joad, a university lecturer,was born in Durham. His father became a school inspector and moved the family to Southampton. Cyril attended the Dragon School, Oxford, and Blundell's School, Tiverton, before entering Balliol College, in 1910, to study philosophy.

Joad later recalled: "Whatever they had to teach me I had assimilated. Admittedly I had learned nothing for myself; but then I had never been encouraged to think that learning for one-self was either possible or desirable. As a result I went up to Oxford ignorant of the major events that have determined the history of the Western world and made our civilization what it is."

According to Jason Tomes: "Greek philosophy fascinated Joad, whose enthusiasm for Plato and Aristotle led not only to a first in literae humaniores (1914) but also to a contemporary brand of radical positivism." Joad was also influenced by the socialist ideas of G. D. H. Cole, H. G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw and in 1912 he joined the Fabian Society. Joad argued that "Shaw became for me a kind of god. I considered that he was not only the greatest English writer of his time (I still think that), but the greatest English writer of all time (and I am not sure that I don't still think that too)."

In his autobiography, Under the Fifth Rib (1932), Joad wrote: "The dominating interest of my University career, an interest which has largely shaped my subsequent outlook on life, was Socialism. And my Socialism was by no means the mere undergraduate pose which what I have said hitherto may have suggested. Admittedly I and my Socialist contemporaries talked a good deal of inflated nonsense; admittedly we played with theories as a child plays with toys from sheer intellectual exuberance. But we also did a considerable amount of hard thinking."

Joad was especially impressed by the writings of G. D. H. Cole. "Cole's Socialism in those days-for all I know, it has been so ever since - was what it is customary to call Left Wing. Already he was finding the Fabian Society timid and slow; soon he was to break away from it and become, with S. G. Hobson, the joint originator of Guild Socialism. Meanwhile he advocated a new militancy in labour disputes, urged that workers should strike in and out of season."

Joad was also a supporter of women's suffrage and he joined the Men's Political Union for Women's Suffrage. He later recalled: "I hobnobbed with emancipated feminists who smoked cigarettes on principle, drank Russian tea and talked with an assured and deliberate frankness of sex and of their own sex experiences, and won my spurs for the movement by breaking windows in Oxford Street for which I spent one night in custody."

Joad left Oxford University in the summer of 1914. "I left Oxford a revolutionary Socialist, convinced that our social arrangements were contemptible, that they were not so of necessity but could be improved, but that nothing short of a change in the economic structure of Society would improve them. Such a change, I considered, would inevitably involve violence and in all probability an armed conflict between classes. This conflict, therefore, I believed - I suppose that I must have believed it; it seems incredible enough to me now - desirable."

In 1914 he found employment in the labour exchanges department of the Board of Trade and talked about "infusing the civil service with a socialist ethos". By this time he had become a pacifist and on the outbreak of the First World War he joined the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), an organisation formed by Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway, that encouraged men to refuse war service. Joad later recalled: "When the war came, I never for a moment thought of it as other than a gigantic piece of criminal folly; the nation, I considered, had simply gone mad, and it was incumbent upon a wise man to stay quiet until the fit had passed. Never for a moment did it occur to me that it was my duty to participate in the madness by learning to fight. On the contrary, I thought that I ought to do whatever I could to avoid being implicated. I was, therefore, a potential conscientious objector from the first, my objection being based not on religious grounds but on a natural reluctance on the part of a would-be rational and intelligent individual to participate in an orgy of public madness."

The No-Conscription Fellowship required its members to "refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms because they consider human life to be sacred." The group received support from public figures such as Bertrand Russell, Philip Snowden, Bruce Glasier, Robert Smillie, C. H. Norman, William Mellor, Arthur Ponsonby, Guy Aldred, Alfred Salter, Duncan Grant, Wilfred Wellock, Maude Royden, Max Plowman and Rev. John Clifford.

As Martin Ceadel, the author of Pacifism in Britain 1914-1945 (1980) has pointed out: "Joad's similarly acute aversion to suffering can be linked to the (heterosexual) hedonism and love of sensual pleasure for which he was notorious. Highly gifted, but restless and opportunistic, he was a puckish and lightweight amalgam of Bertrand Russell (who believed Joad plagiarized his ideas) and H. G. Wells, tending to the former's iconoclastic optimism rather than to the latter's Olympian seriousness."

Joad married Mary White in 1915 and moved to Westhumble, near Dorking. Over the next few years she gave birth to a son and two daughters. Joad joined the Independent Labour Party and contributed book reviews and articles to left-wing journals, such as the Daily Herald and New Statesman. He also wrote two books on philosophy, Common Sense Ethics (1921) and Common Sense Theology (1922). Jason Tomes has argued: "Joad declared Christianity moribund and rejoiced that clergymen would be extinct by 1960. Unreason in every shape was his foe: superstition, romanticism, psychoanalysis, and also outmoded social convention... What reforms did reason require? Easier divorce and birth control, legalized abortion and sodomy, an end to Sunday trading laws and performing animals, sterilization of the feeble-minded, total disarmament, and less frequent baths."

Joad left his wife in 1921 and moved to Hampstead in London with a student teacher named Marjorie Thomson. This was the first of many mistresses. His biographer has pointed out: "Sexual desire, he opined, resembled a buzzing bluebottle that needed to be swatted promptly before it distracted a man of intellect from higher things... Female minds lacked objectivity; he had no interest in talking to women who would not go to bed with him. A surprising number would - notwithstanding his increasingly gnome - like appearance. Joad was short and rotund, with bright little eyes, round, rosy cheeks, and a stiff, bristly beard. He dressed in old tweeds of great shabbiness as a test: anyone who sneered at his clothing was too petty to merit acquaintance."

In 1925 Joad was expelled from the Fabian Society for sexual misbehaviour during a summer school he was attending. He admitted in his autobiography, Under the Fifth Rib (1932): "I started my adult life, as I have recounted, with such high hopes of women, that the process of disillusionment has left a bitterness behind. If I was never sentimental enough to expect women to be soul mates, at least I thought to treat them as intellectual equals. It was a shock to find that the equality had been imposed by myself upon unequals who resented it. If only women could have remained at the silent-film stage, all would have been well; but the invention of talking has been as disastrous in women as it has in the cinema."

Joad remained a socialist and went to visit the Soviet Union in 1930. "There were no rich and in the towns no poor; all citizens were living on incomes ranging from about, £100 to £200 a year. What is more, the Bolsheviks had succeeded in establishing a society in which the possession of money had been abolished as a criterion of social value. The effects were far-reaching, and, so far as I could see, entirely beneficial. The snobbery of wealth, which is so important a factor in the social life of Anglo-Saxon communities, was absent. There was no ostentation and no display, and the contemporary fat man, complete with fur coat, white waistcoat, champagne and cigars, was missing. It was only when one returned to England that one realized by contrast the vulgarity of wealth... The Russians, admittedly, are poor and live badly, but the sting is removed from poverty if it is not outraged by the continual spectacle of others' wealth. I cannot believe that complete equality of income would not produce similar effects here, and, if snobbery and vulgarity were eliminated from English society, the gain would be incalculable." However, as a pacifist he rejected the idea of violent revolution.

In 1930 Joad obtained the post of head of philosophy at Birkbeck College. Joad retained an interest in politics and impressed with the views of Oswald Mosley he joined his New Party. In 1932 Joad set up the Federation of Progressive Societies and Individuals (FPSI). According to Martin Ceadel, the organisation was "an attempt - with the master's blessing - to implement the Wellsian vision of an enlightened elite of intellectuals uniting to plan rational solutions for the problems of the world."

In January 1932 Mosley met Benito Mussolini in Italy. Mosley was impressed by Mussolini's achievements and when he returned to England he disbanded the New Party and replaced it with the British Union of Fascists. Joad was horrified with Mosley's move towards fascism and along with John Strachey refused to join the BUF.

Joad remained a pacifist and was a member the of the National Peace Council, No More War, the National Civil Liberties Union and the Next Five Years Group. On 9th February 1933 he persuaded the Oxford Union to resolve by 275 votes to 153 "That this house will under no circumstances fight for its King and Country".

With his books, Guide to Modern Thought (1933) and Guide to Philosophy (1936), Joad became Britain's most popular philosopher. He remained a pacifist and he wrote a pamphlet during this period entitled What Fighting Means about the First World War: "Men were burned and tortured; they were impaled, blinded, disembowelled, blown to fragments; they hung shrieking for days and nights on barbed wire with their insides protruding, praying for a chance bullet to put an end to their agony; their faces were blown away and they continued to live."

Joad had a terrible fear of the growth of fascism in Europe and was a supporter of the Popular Front government in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. He joined with Emma Goldman, Rebecca West, Sybil Thorndyke and Fenner Brockway to establish the Committee to Aid Homeless Spanish Women and Children.

Joad was deeply shocked by the way the West had allowed Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini to help Francisco Franco gain power in Spain. He abandoned his pacifism as he felt it was contributing to the inevitability of war. As his old friend Fenner Brockway pointed out: "There is no doubt that the society resulting from an anarchist victory (during the Spanish Civil War) would have far greater liberty and equality than the society resulting from a fascist victory. Thus I came to see that it is not the amount of violence used which determines good or evil results, but the ideas, the sense of human values, and above all the social forces behind its use. With this realisation, although my nature revolted against the killing of human beings just as did the nature of those Catalonian peasants, the fundamental basis of my old philosophy disappeared."

On the outbreak of the Second World War he offered his services to the Ministry of Information. This idea was rejected but in January 1941, Joad became a member of the panel of the BBC radio programme The Brains Trust. The programme was a great success and Joad became a well-known public figure. His favourite expression, "It depends what you mean by..." became a popular catch-phrase. However, the Conservative Party complained about his "socialistic" answers.

After the war he purchased a farm in Hampshire. He rejoined the Labour Party but lost a by-election for the Combined Scottish Universities in 1946. Joad continued to write and blamed President Harry Truman for the Cold War and the nuclear arms race.

On 12th April 1948, Joad was convicted of "unlawfully travelling on the railway without having previously paid his fare and with intent to avoid payment." He was fined £2 but as a result of the conviction he was sacked from The Brains Trust team. He was also told that he had lost all chance of gaining a peerage.

Joad was now in poor health and was confined to bed. In 1952 he published The Recovery of Belief. In the book he endorsed Christianity and the Anglican Church. He died of cancer at his home, 4 East Heath Road, Hampstead, London, on 9th April 1953. As Jason Tomes has pointed out: "Cyril Joad was an outstanding educator, a tireless proponent of progressive causes, and one of the best-known broadcasters of the 1940s. His religious conversion alienated radical agnostics who might otherwise have kept his reputation alive."

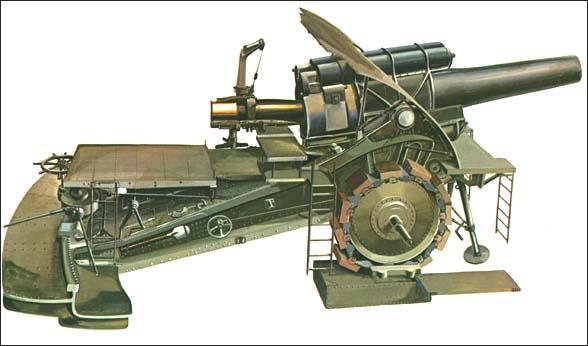

On this day in 1914 Big Bertha fired its first shells at Liege in Belgium. By 1912 Krupp had produced a 420mm weapon that fired a 2,100 lb shell over 16,000 yards. As it weighed 175 tons, it was designed to be transported in five sections by rail and assembled at the firing site. This concerned the German Army and they asked for it to be adapted to be moved by road. By 1914 company had produced a mobile howitzer called Big Bertha (named after Gustav Krupp's wife). This 43 ton howitzer could fire a 2,200 lb shell over 9 miles. Transported by Daimler-Benz tractors, it took its 200-man crew, over six hours to re-assemble it on the site.

On the outbreak of the First World War, two Big Berthas and several Skoda 30.5 howitzers were erected outside the fortress of Liege in Belgium. The first shells were fired on 12th August at the ring of 12 forts around the city. By the 15th August all the forts had either been destroyed or had surrendered. News of the success of this new weapon at Liege encouraged other countries involved in the conflict to produce large mobile guns.

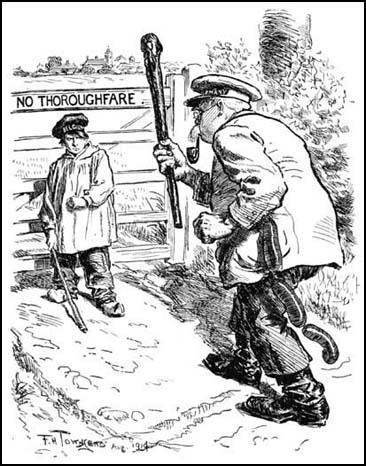

On this day in 1914 F. H. Townsend publishes famous cartoon, No Thoroughfare after the German invasion of Belgium.

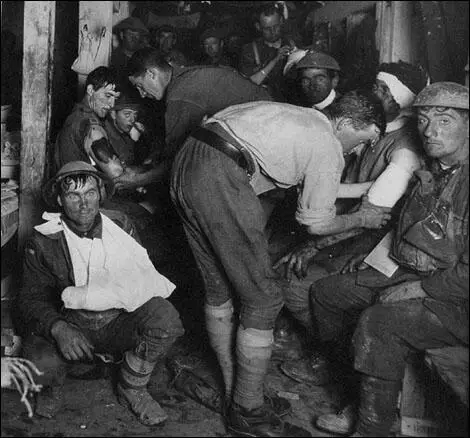

On this day in 1916 John Raws writes about shellshock.

The Australian casualties have been very heavy - fully 50% in our brigade, for the ten or eleven days. I lost, in three days, my brother and my two best friends, and in all six out of seven of all my officer friends (perhaps a score in number) who went into the scrap - all killed. Not one was buried, and some died in great agony. It was impossible to help the wounded at all in some sectors. We could fetch them in, but could not get them away. And often we had to put them out on the parapet to permit movement in the shallow, narrow, crooked trenches. The dead were everywhere. There had been no burying in the sector I was in for a week before we went there.

The strain - you say you hope it has not been too great for me - was really bad. Only the men you would have trusted and believed in before, proved equal to it. One or two of my friends stood splendidly like granite rocks round which the seas stormed in vain. They were all junior officers. But many other fine men broke to pieces. Everyone called it shell shock. But shell shock is very rare. What 90% get is justifiable funk, due to the collapse of the helm - of self-control. I felt fearful that my nerve was going at the very last morning. I had been going - with far more responsibility than was right for one so inexperienced - for two days and two nights, for hours without another officer even to consult and with my men utterly broken, shelled to pieces.

On this day in 1918 Guy Gibson, the son of a civil servant, was born. Educated at St Edward's School in Oxford, he joined the Royal Air Force in 1936 and by the outbreak of the Second World War had become a bomber pilot with 83 Squadron.

Gibson won the Distinguished Flying Cross in July 1940 on Bomber Command's first raid of the war. After completing his first tour of duty he avoided the normal six-month rest from operations at a flying training establishment by obtaining a transfer to Fighter Command. In his new role as a night fighter he obtained four kills and won a bar to his DFC.

At the age of 23 Gibson was promoted to the rank of wing commander and in April 1942 was posted back to Bomber Command. Over the next eleven months he led 106 Squadron and flew 172 sorties before taking over the 617 Squadron.

In February, 1943, the Royal Air Force decided to plan an attack on the five hydroelectric dams on which the Ruhr industrial area depended. Barnes Wallis advised the Royal Air Force to use the new bouncing bomb he had been developing at the National Physics Laboratory in Teddington.

Guy Gibson was selected to take part in Operation Chastise (also known as Dambusters Raid). The targets were the three key dams near the Ruhr area, the Möhne, the Sorpe and the Eder Dam on the Eder River. It was hoped that the raid would result in the loss of hydroelectric power and the supply of water to nearby cities. The success of the operation involved precision bombing. The cylindrical bombs developed by Barnes Wallis had to be dropped from 60 feet to skip into the dam face and roll down it to explode at a depth that triggered a pressure fuse. The pilots had to judge the critical release point by using dual spotlights whose beams converged vertically at 60 feet.

The aircraft used were adapted Avro Lancasters. To reduce weight, much of the armour was removed, as was the mid-upper turret. The substantial bomb and its unusual shape meant that the bomb doors were removed and the bomb itself hung, in part, below the body of the aircraft. The crews practised over the Eyebrook Reservoir, the Derwent Reservoir and the Fleet Lagoon at Chesil Beach. The final test flights took place on 29th April 1943.

Operation Chastise began on the night of 15-16th May. The first wave of aircraft, led by Guy Gibson, would first attack the Möhne Dam. The second group was to attack the Sorpe Dam whereas the third group was a mobile reserve and would take off two hours later, either attacking the main dams or bombing smaller dams at Schwelm, Ennepe and Diemel.

Two aircraft piloted by Les Munro and Geoff Rice were forced to return to base following technical problems. Robert Barlow and Vernon Byers were shot down and crashed into the Waddenzee, whereas Bill Astell came down somewhere over Roosendaal.

The first group of aircraft piloted by Guy Gibson, Melvin Young, John Hopgood, Mick Martin, David Shannon, Henry Maudslay, David Maltby and Les Knight arrived safely at their first target. Gibson bombed first but it failed to hit the Möhne Dam. During his run Hopgood aircraft was hit by flak and destroyed. Gibson now flew his aircraft across the dam to draw flak from Martin's run. Martin's aircraft was hit but he made a successful attack.

Melvin Young was the next man to go. Guy Gibson recorded that Young's bomb made "three good bounces and made contact (with the dam)." A huge column of water rose and a shock wave could be seen rippling through the lake. The dam was now beginning to break but it did not collapse immediately. David Maltby was now ordered to attack the dam. He later said that "the crown of the wall was already crumbling" and that he could see a "breach in the centre of the dam" before dropping his bomb. Gibson radioed back to headquarters that he could now see a great gap, some 150 metres long, in the dam and a torrent of water that looked "like stirred porridge in the moonlight."

Guy Gibson then led Melvin Young, David Shannon, Henry Maudslay and Les Knight to the Eder Dam. The topography of the surrounding hills made the approach difficult and the first aircraft, Shannon's, made several unsuccessful runs without dropping his bomb. Shannon later recalled: "The Eder was a bugger of a job. I was the first to go; I tried three times to get a spot on approach but was never satisfied. To get out of the valley after crossing the dam wall we had to put on full throttle and do a steep climbing turn to avoid a vast rock face. My exit with a 9000lb bomb revolting at 500rpm was bloody hairy."

Gibson ordered David Shannon to take a break and called up Henry Maudslay to have a go. After Maudslay had two unsuccessful runs, Shannon made another attempt and this time he released his bomb and it hit the target. Maudslay made another run but his bomb hit the top of the dam and the aircraft was caught in the blast.

Only Les Knight had a bomb left. His first run ended in failure but the next one resulted in the bomb hitting the dam. Guy Gibson later recalled: "We saw the tremendous earthquake which shook the base of the dam, and then, as if a gigantic hand had punched a hole through cardboard, the whole thing collapsed."

Joe McCarthy reached the Sorpe alone. It was the most difficult to breach as it was a vast earth dam rather than the concrete structures of the Mohne and Eder dams. McCarthy's aircraft successfully dropped its bomb but it did little damage. Three of the reserve aircraft were directed to the Sorpe. However, they were unable to breach the dam.

Meanwhile, Guy Gibson, Melvin Young, David Shannon, and Les Knight were involved in a dangerous journey to get back to England. Henry Maudslay had started off earlier after his aircraft had been badly damaged while bombing the Eder Dam. However, he was shot down close to the German-Dutch border. At 02.58 gunners at Castricum-aan-Zee managed to hit Young's aircraft. It crashed into the sea and all its crew were killed. Another three were captured and ended the war in prison camps.

Only 11 of Gibson's 19 bombers survived the mission. Eight aircraft had been lost and 53 flyers had been killed in the operation.

Gibson was awarded the Victoria Cross for his role in the Dambusters mission. Sent on a lecture tour of the United States, he wrote the book, Enemy Coast Ahead and became prospective Conservative Party candidate for Macclesfield.

Gibson returned to duty in June 1944. On the 19th September, 1944, Gibson flew his De Havilland Mosquito as master bomber in a raid on Rheydt. He never arrived home and later it was discovered that Gibson and his navigator, James Warwick, had been killed when the plane crashed in the Netherlands.

On this day in 1958 historian Mary Ritter Beard died.

Mary Ritter, the daughter of Eli Ritter, a lawyer, and Narcissa Lockward, a schoolteacher, was born in Indianapolis on 5th August 1876. While at DePauw University she met Charles Beard. After their marriage in 1900 the couple moved to England where Beard continued his studies at Oxford University.

The Beards lived in Oxford and Manchester, where they became close friends of Emmeline Pankhurst and her two daughters, Christabel Pankhurst and Sylvia Pankhurst. At the time the women were members of the socialist reform group, the Independent Labour Party. They were also active in the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), but later formed the more militant Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

The couple returned to the United States in 1904 to continue graduate studies at Columbia University. Inspired by the work of the Pankhursts and the Independent Labour Party, Mary became involved in the struggle for women's suffrage and social reform.

In 1907 Beard began working for the Women's Trade Union League, an organization that was attempting to educate women about the advantages of trade union membership. The organization also supported women's demands for better working conditions and tried to raise awareness about the exploitation of women workers. Other leading figures in the organization included Jane Addams, Margaret Robins, Mary McDowell, Margaret Haley, Helen Marot, Agnes Nestor, Florence Kelley and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

Beard also joined the American Woman Suffrage Association and in 1910 became editor of its New York journal, the Women Voter. Beard was able to persuade a large number of talented writers and artists to contribute to the journal including Ida Proper, John Sloan, Mary Wilson Preston, James Montgomery Flagg, Robert Minor, Clarence Batchelor, Cornelia Barnes and Boardman Robinson.

Disillusioned with the failure of the American Woman Suffrage Association to achieve the vote for women, Beard joined in 1913 with Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, Mabel Vernon, Olympia Brown, Belle LaFollette, Helen Keller, Maria Montessori, Dorothy Day and Crystal Eastman to form the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage (CUWS). It was decided that the CUWS should employ the militant methods used by Emmeline Pankhurst and the Women's Social and Political Union in Britain. This included organizing huge demonstrations and the daily picketing of the White House. Over the next couple of years the police arrested nearly 500 women for loitering and 168 were jailed for "obstructing traffic".

Beard spent much of her time writing and in 1915 published Woman's Work in the Municipalities. This was followed by A Short History of the Labor Movement (1920). Working with Charles Beard, she wrote a two volume history of the United States, The Rise of American Civilization (1927). This was followed by America in Midpassage (1939) and The American Spirit (1942). The couple also collaborated on A Basic History of the United States (1944).

Mary and Charles Beard were proponents of what became known as the New History. They challenged the primacy of military and political explanations of the past by examining economic and social factors in more detail. In Beard's books she demonstrated the central role that women had played in history. This was reflected in her book On Understanding Women (1931) and America Through Women's Eyes (1933), a collection of accounts by women who had played an integral part in the development of America's history.

In On Understanding Women she highlighted a problem that faced feminist historians. "Women have been engaged in a continuous contest to defend their arts and crafts, to win the right to use their minds and to train them, to obtain openings for their talents and to earn a livelihood, to break through legal restraints on their unfolding powers. In their quest for rights women have naturally placed emphasis on their wrongs, rather than their achievements and possessions, and have retold history as a story of their long Martyrdom. Feminists have been prone to prize and assume the traditions of those with whom they had waged such a long, and in places bitter conflict. In doing so, they have participated in a distortion of history and a disturbance of the balanced conceptual thought which gives harmony and power to life."

Beard was a strong supporter of women's education and in 1934 published A Changing Political Economy as it Affects Women, which was a detailed syllabus for a women's studies course. However, despite a great deal of campaigning, she was unable to persuade any college or university to adopt what would have been America's first women's studies course.

In 1935 Beard joined with the veteran peace campaigner, Rosika Schwimmer, to create the World Centre for Women's Archives. The main objective for the centre was to preserve the records of women's contributions to history. They chose the motto for the archive: "No documents, no history." The venture was brought to an end in 1940 as a result of her failure to raise enough funds to pay for the centre.

Beard's next project was to analyze how the Encyclopaedia Britannica had systematically excluded the role of women. For example, she claimed that the entry for the 'American Frontier' was "extremely narrow and bigoted" and ignored "women's civilizing role" and the "co-operative enterprises which elevated the individualistic will to social prowess". Beard also criticised the omissions of subjects such as Hull House from the Encyclopaedia Britannica. She worked for 18 months on a multi-disciplinary critique of the information in the encyclopaedia, but her report, A Study of the Encyclopaedia Britannica in Relation to its Treatment of Women, was ignored by the company.

Beard was an active member of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. Although a strong anti-fascist, Mary, like her husband, Charles Beard, was opposed to the United States involvement in the Second World War.

Beard's most important book Woman as Force in History: A Study of Traditions and Realties was published in 1946. In the book she attacked historians and social scientists for the misuse of the generic man and for their omissions and distortions of the record of women. She pointed out that women of the ruling class often wielded great power, and women suffered as much or more from from their class position as from their gender. It was with the development of capitalism, she argued, that "discrimination on account of sex, regardless of class, became pervasive."

This was followed by The Force of Women in Japanese History (1953). After the death of Charles Beard she published the book, The Making of Charles Beard (1955).

On this day in 1964 Ian Fleming died from a heart-attack. At the time of his death Fleming had sold 30 million books. In 1965 over 27 million copies of Fleming's novels were sold in eighteen different languages, producing an income of £350,699. In less than two years, his sales more than doubled those he had achieved in his lifetime. People continued to watch Dr No and it went on to gross $16 million around the world.

Ian Fleming, the second of four sons of Valentine Fleming (1882–1917) and Evelyn Beatrice Ste Croix (1885–1964), was born on 28th May, 1908. His grandfather was Robert Fleming, an extremely wealthy banker. The family lived at Braziers Park, a large house at Ipsden in Oxfordshire.

Ian's father was active in the Conservative Party and in 1910 he became the member of the House of Commons for South Oxfordshire. A fellow member of parliament, Winston Churchill, pointed out that Fleming was "one of those younger Conservatives who easily and naturally combine loyalty to party ties with a broad liberal outlook upon affairs and a total absence of class prejudice... He was a man of thoughtful and tolerant opinions, which were not the less strongly or clearly held because they were not loudly or frequently asserted.... He could not share the extravagant passions with which the rival parties confronted each other. He felt that neither was wholly right in policy and that both were wrong in mood." On the outbreak of the First World War Fleming joined the Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars.

Fleming was educated at Durnford Preparatory School and in 1917 he met Ivar Bryce on a beach in Cornwall: "The fortress builders generously invited me to join them, and I discovered that their names were Peter, Ian, Richard and Michael, in that order. The leaders were Ian and Peter, and I gladly carried out their exact and exacting orders. They were natural leaders of men, both of them, as later history was to prove, and it speaks well for them all that there was room for both Peter and Ian in the platoon."

In May 1917 Fleming heard news that his father, Valentine Fleming, had been killed while fighting on the Western Front. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Order. Fleming went to Eton College but as his biographer, Andrew Lycett, has pointed out: "At Eton he showed little academic potential, directing his energies into athletics, becoming victor ludorum two years in succession, and into school journalism."

While at Eton he became a close friend of Ivar Bryce. He purchased a Douglas motorbike and used this vehicle for trips around Windsor. He also took Fleming on the bike to visit the British Empire Exhibition in London. They also published a magazine, The Wyvern , together. Fleming used mother's contacts to persuade Augustus John and Edwin Lutyens, to contribute drawings. The magazine also published a poem by Vita Sackville-West. The editors showed their right-wing opinions by publishing an article in praise of the British Fascisti Party. It argued that its "primary intention is to counteract the present and every-growning trend towards revolution... it is of the utmost importance that centres should be started in the universities and in our public schools".

His mother decided he was unlikely to follow his brother, Peter Fleming to Oxford University, and arranged for him to attend the Sandhurst Royal Military College. However, he was not suited to military discipline and left without a commission in 1927, following an incident with a woman in which, to his mother's horror, he managed to contract a venereal disease.

His mother, Eve Fleming inherited her husband's large estate in trust, making her very wealthy. This did come with conditions that stated she would lose this money if she remarried. She became the mistress of painter Augustus John with whom she had a daughter, the cellist Amaryllis Fleming.

Fleming was sent to study in Kitzbühel, Austria, where he met Ernan Forbes Dennis, a former British spy turned educationist, and his wife, Phyllis Bottome, an established novelist. It was while staying with the couple that he first considered a career as a writer. Fleming later wrote to Phyllis: "My life with you both is one of my most cherished memories, and heaven knows where I should be today without Ernan."

After studying briefly at the universities in Munich and Geneva, Fleming considered becoming a diplomat but he failed the competitive examination for the Foreign Office. His mother used her contacts to get him work as a journalist. This included reporting on the trial of six engineers working for a British company, Metropolitan-Vickers, who had been accused of spying in the Soviet Union. While in Moscow he attempted to get an interview with Joseph Stalin. After this rejection he returned to London.

In August 1935 Fleming met Muriel Wright while on holiday at Kitzbühel. Over the next four years they spent a great deal of time together. Fleming was dazzled by her looks but did not find her very stimulating company and continued to have relationships with other women, this included Mary Pakenham and Ann O'Neill, the wife of Shane Edward Robert O'Neill. Pakenham later recalled that he had two main topics of conversation - himself and sex: "He was always trying to show me obscene pictures of one sort or another. No one I have known has had sex so much on the brain as Ian in those days." Muriel's brother, Fitzherbert Wright, heard about the way Fleming was treating his sister and arrived at Ian's flat with a horsewhip. He was not there as he had taken Muriel to Brighton for the weekend.

Eve Fleming insisted her son sought a career in the family business of banking. He worked briefly for a small bank before joined Rowe and Pitman, a leading firm of stockbrokers. He hated the work and on the outbreak of the Second World War a family friend, the Governor of the Bank of England, Montagu Norman, arranged for Fleming to join the naval intelligence division as personal assistant to Admiral John Godfrey, the director of naval intelligence.

According to the author of Ian Fleming (1996): "With his charm, social contacts, and gift for languages, Fleming proved an excellent appointment. Working from the Admiralty's Room 39, he showed a hitherto unacknowledged talent for administration, and was quickly promoted from lieutenant to commander. He liaised on behalf of the director of naval intelligence with the other secret services. One of few people given access to Ultra intelligence, he was responsible for the navy's input into anti-German black propaganda."

It has been claimed that Fleming was involved in the plot to lure Rudolf Hess to Britain. Richard Deacon, the author of Spyclopaedia: The Comprehensive Handbook of Espionage (1987), has argued: "The truth is that a number of wartime intelligence coups credited to other people were really manipulated by Fleming. It was he who originated the scheme for using astrologers to lure Rudolf Hess to Britain. Fleming's contract in Switzerland succeeded in planting on Hess an astrologer who was also a British agent. To ensure that the theme of the plot was worked into a conventional horoscope the Swiss contract arranged for two horoscopes of Hess to be obtained from astrologers known to Hess personally so that the faked horoscope would not be suspiciously different from those of the others."

Fleming worked with Colonel Bill Donovan, the special representative of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on intelligence co-operation between London and Washington before Pearl Harbor. Fleming met William Stephenson and Ernest Cuneo in New York City in the summer of 1940. Fleming criticised Admiral Ernest King, Chief of US naval operations for not supporting the Russian convoys forcefully enough. Cuneo responded by claiming that Fleming was only a junior officer who was unlikely to know enough about the subject. Fleming commented: "Do you question my bona fides?" Fleming asked angrily. "No, only your patently limited judgement." Despite this exchange the two men soon became close friends.

Cuneo described Fleming as having the appearance of a lightweight boxer. It was not only his broken nose but the way he carried himself: "He did not rest his weight on his left leg; he distributed it, his left foot and his shoulders slightly forward." Cuneo liked Fleming's "steely patriotism" and told General William Donovan that he was a typical English agent: "England was not a country but a religion, and that where England was concerned, every Englishman was a Jesuit who believed the end justified the means." In May 1941 Fleming accompanied Admiral John Godfrey to America, staying to help write a blueprint for the Office of Co-ordinator of Information (the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency).

During the Second World War Fleming's great friend, Ivar Bryce worked as an SIS agent attached to William Stephenson in New York City. It is claimed that based in Jamaica (his wife Sheila, owned Bellevue, one of the most important houses on the island), Bryce ran dangerous missions into Latin America. Fleming visited Bryce in 1941 and told him that: "When we have won this blasted war, I am going to live in Jamaica. Just live in Jamaica and lap it up, and swim in the sea and write books."

In 1942 Fleming was instrumental in forming a unit of commandos, known as 30 Commando Assault Unit (30AU), a group of specialist intelligence troops, trained by the Special Operations Executive (SOE). The unit was based on a German group headed by Otto Skorzeny, who had undertaken similar activities for Nazi Germany. The unit was initially deployed for the first time during the Dieppe Raid in August 1942, and then took part in the Operation Torch landings in November 1942. The unit went on to serve in Norway, Sicily, Italy, and Corsica between 1942–1943. In June 1944 they took part in the D-Day landings, with the objective of capturing a German radar station at Douvres-la-Delivrande.

During the war, Fleming's girlfriend, Muriel Wright became an air raid warden in Belgravia. However, according to a friend she found the uniform unflattering. She now became a small team of despatch riders at the Admiralty who roared around London on BSA motorcycles. Muriel was killed during an air raid in March 1944. Andrew Lycett, the author of Ian Fleming (1996) has pointed out: "All such casualties are, by definition, unlucky, but she was particularly so, because the structure of her new flat at 9 Eaton Terrace Mews was left intact. She died instantly when a piece of masonry flew in through a window and struck her full on the head. Because there was no obvious damage, no one thought to look for the injured or dead; it was only after her chow, Pushkin, was seen whimpering outside that a search was made. As her only known contact, Ian was called to identify her body, still in a nightdress. Afterwards he walked round to the Dorchester and made his way to Esmond and Ann's room. Without saying a word he poured himself a large glass of whisky, and remained silent. He was immediately consumed with grief and guilt at the cavalier way he had treated her." His friend, Dunstan Curtis, commented: "The trouble with Ian is that you have to get yourself killed before he feels anything."

Ian Fleming was also having an affair with Ann O'Neill, the wife of Lieutenant Colonel Shane Edward Robert O'Neill. He was killed in Italy in October 1944. Although she then went on to marry Esmond Cecil Harmsworth, heir to Lord Rothermere, the owner of The Daily Mail, Fleming continued to see Ann on a regular basis.

After the war Fleming joined the Kemsley Newspaper Group as foreign manager. His friend, Ivar Bryce, helped Fleming find a holiday home and twelve acres of land just outside of Oracabessa. It included a strip of white sand on a lovely part of the coast. Fleming decided to call the house, Goldeneye, after his wartime project in Spain, Operation Goldeneye. Their former boss, William Stephenson, also had a house on the island overlooking Montego Bay. Stephenson had set up the British-American-Canadian-Corporation (later called the World Commerce Corporation), a secret service front company which specialized in trading goods with developing countries. William Torbitt has claimed that it was "originally designed to fill the void left by the break-up of the big German cartels which Stephenson himself had done much to destroy."

Fleming continued her affair with Ann Harmsworth. She told her husband she was staying with Fleming's neighbour, Noël Coward. Ann wrote to Fleming in 1947 after one of her visits: "It was so short and so full of happiness, and I am afraid I loved cooking for you and sleeping beside you and being whipped by you... I don't think I have ever loved like this before." Fleming replied: "All the love I have for you has grown out of me because you made it grow. Without you I would still be hard and dead and cold and quite unable to write this childish letter, full of love and jealousies and adolescence." In 1948 Ann gave birth to his daughter, Mary, who lived only a few hours.

Fleming negotiated a favourable contract with Kemsley Newspaper Group that allowed him to take three months' holiday every winter in Jamaica. Fleming loved the time he spent at Goldeneye: "Every exploration and every dive results in some fresh incident worth the telling: and even when you don't come back with any booty for the kitchen, you have a fascinating story to recount. There are as many stories of the reef as there are fish in the sea."

After the war Ernest Cuneo joined with Ivar Bryce and a group of investors, including Fleming, to gain control of the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA). Andrew Lycett has pointed out: "With the arrival of television, its star had begun to wane. Advised by Ernie Cuneo, who told him it was a sure way to meet anyone he wanted, Ivar stepped in and bought control. He appointed the shrewd Cuneo to oversee the American end of things... and Fleming was brought on board to offer a professional newspaperman's advice." Fleming was appointed European vice-president, with a salary of £1,500 a year. He persuaded James Gomer Berry, 1st Viscount Kemsley, that The Sunday Times should work closely with NANA. He also organized a deal with The Daily Express, owned by Lord Beaverbrook.

Fleming considered the possibility of writing detective fiction. In December 1950 he travelled to New York City to meet with Ernest Cuneo and William Stephenson. Fleming's biographer points out: "With William Stephenson's and Ernie Cuneo's help - Ian spent a night out on the Upper West Side with a couple of detectives from the local precinct. On previous trips he had enjoyed visiting Harlem dance clubs, where he delighted in their energy as much as their music. Now his eyes had been opened to a seedier reality. He met a local crime boss and witnessed with alarm the hold that drug traffickers were gaining in the neighbourhood." Cuneo took the opportunity to tell Fleming that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was a communist front.

Fleming often visited the United States to be with Cuneo. This included doing research in Las Vegas for a novel he was planning. Cuneo argued that Fleming was "a knight errant searching for the lost Round Table and possibly the Holy Grail, and unable to reconcile himself that Camelot was gone and still less that it had probably never existed."

In 1951 Esmond Cecil Harmsworth, who discovered her relationship with Fleming, divorced Ann. Her £100,000 divorce settlement enabled her to live in luxury with the unemployed Fleming. On 24th March 1952 she married Fleming. The very next day, he sat down and began writing Casino Royale. Ann wrote in her diary: "This morning Ian started to type a book. Very good thing." Every morning after a swim he breakfasted with Ann in the garden. After he finished his scrambled eggs, he settled in the main living-room and for the next three hours he "pounded the keys" of his twenty-year-old portable typewriter. He took lunch at noon and afterwards slept for an hour or so. He then returned to his desk and corrected what he had written in the morning.

John Pearson, the author of The Life of Ian Fleming (1966) claims that Fleming wrote a 62,000 word manuscript in eight weeks. He later claimed that he wrote Casino Royale in order to take his mind of being married. Andrew Lycett has argued that in reality, there were other reasons for this burst in creativity: "It was not so much his marriage that spurred Ian as the fait accompli of Ann's pregnancy, which created a new set of circumstances, partly physical - with her need to take her pregnancy carefully, she was hors de combat sexually, so Ian had time and energy on his hands - and partly psychological - Ian realized that, at the age of forty-three, the imminent arrival of his first-born child would change his life more radically than anything he had done before. With no great financial resources behind him, he needed to provide for his off-spring, whatever sex it turned out to be. Casino Royale was to be his child's birthright."

Fleming's novel, Casino Royale, featuring the secret agent James Bond, was published to critical acclaim in April 1953. Fleming later admitted that Bond was based on his wartime colleague, William Stephenson: "James Bond is a highly romanticized version of a true spy. The real thing is... William Stephenson." The 'M' character was inspired by Maxwell Knight, the head of B5b, a unit that conducted the monitoring of political subversion. The Flemings bought a Regency house in Victoria Square, London, and Ann Fleming gained a reputation for giving lunch and dinner parties attended by new literary friends, including Cyril Connolly and Evelyn Waugh.

Barbara Skelton, the wife of George Weidenfeld, and a published novelist, was one of the many visitors to Goldeneye. Unlike most women she did not find Ian attractive: "His eyes were too close together and I don't fancy his raw beef complexion." She accepted that Ann was attractive and "well-bred" but added, "why does she always rouge her cheeks like a painted doll?"

Fleming gave an insight into the writing process when he gave Ivar Bryce advice on writing his memoirs: "You will be constantly depressed by the progress of the opus and feel it is all nonsense and that nobody will be interested. Those are the moments when you must all the more obstinately stick to your schedule and do your daily stint... Never mind about the brilliant phrase or the golden word, once the typescript is there you can fiddle, correct and embellish as much as you please. So don't be depressed if the first draft seems a bit raw, all first drafts do. Try and remember the weather and smells and sensations and pile in every kind of contemporary detail. Don't let anyone see the manuscript until you are very well on with it and above all don't allow anything to interfere with your routine. Don't worry about what you put in, it can always be cut out on re-reading; it's the total recall that matters."

The journalist, Christopher Hudson, has claimed the Flemings were practitioners of sadomasochism: "Those who were lucky enough to visit Goldeneye, Ian Fleming's Jamaican retreat, could never understand how the Flemings went through so many wet towels. But those sodden towels were needed, literally, to cool their fiery partnership, used to relieve the stinging of the whips, slippers and hairbrushes the pair beat each other with - Ian inflicting pain more often than Ann - as well as to cover up the weals Ian made on Ann's skin during their fiery bouts of love-making." She wrote to Fleming: "I long for you to whip me because I love being hurt by you and kissed afterwards. It's very lonely not to be beaten and shouted at every five minutes." Hudson goes on to argue: "The pregnancy which led to their marriage resulted in Caspar, their first and only child. The birth, Ann's second Caesarian, left wide scars on her stomach, to the disgust of Fleming who had a horror of physical abnormality. Ann said it marked the end of their love-making."

Fleming followed Casino Royale with Diamonds Are Forever (1956). It received mixed reviews. Anthony Boucher wrote in the New York Times that Fleming "writes excellently about gambling, contrives picturesque incidents but the narrative is loose-joined and weekly resolved". Fleming defended himself by claiming that he was writing "fairy tales for grown-ups."

From Russia With Love appeared in 1957 and Dr No in 1958. Ann Fleming spent her time painting while Fleming wrote his books. She told Evelyn Waugh, "I love scratching away with my paintbrush while Ian hammers out pornography next door.

Fleming's biographer, Andrew Lycett, has argued: "Bond reflected much of Fleming: his secret intelligence background, his experience of good living, his casual attitude to sex. He differed in one essential - Bond was a man of action, while Fleming had mostly sat behind a desk. Fleming's news training was evident in his lean, energetic writing (with its dramatic set-piece essays on subjects that interested him, such as cards or diamonds) and in his desire to reflect contemporary realities, not only politically but sociologically. He was aware of Bond's position as a hard, often lonely professional, bringing glamour to the grim post-war 1950s. Fleming broke new ground in giving Bond an aspirational lifestyle and larding it with brand names."

Fleming spent a lot of time in Jamaica where he had an affair with Millicent Rogers, the granddaughter of Standard Oil tycoon Henry Huttleston Rogers, and an heiress to his wealth. He also had relationships with Jeanne Campbell and the novelist, Rosamond Lehmann. However, his most important relationship was with Blanche Blackwell who he met in 1956. Blanche described him as a fine physical specimen, "six foot two inches tall, with blue eyes and coal black hair, and so rugged and full of vitality." Blanche told Jane Clinton: “Don’t forget I met him when he was 48. In his early life I believe he did not behave terribly well. I knew an Ian Fleming that I don’t think a lot of people had the good fortune to know. I didn’t fawn over him and I think he liked that.... She (Ann Fleming) disliked me but I can’t blame her. When I got to know Ian better I found a man in serious depression. I was able to give him a certain amount of happiness. I felt terribly sorry for him.”

Sebastian Doggart has claimed that Blackwell was "the inspiration for Dr. No's Honeychile Ryder, whom Bond first sees emerging from the waves – naked in the book, bikini-clad in the movie." As well as Honeychile Ryder it has been argued that Fleming based the character of Pussy Galore , who appeared in Goldfinger on Blackwell.

Ann Fleming developed an interest in politics through her friend Clarissa Churchill, who had married Sir Anthony Eden, the leader of the Conservative Party. However during this period she began an affair with Hugh Gaitskell, the leader of the Labour Party. Brian Brivati, the author of Hugh Gaitskell (1996) has pointed out: "Friends and close colleagues worried both that the liaison would damage Gaitskell politically and that the kind of society life that Fleming lived was far removed from the world of Labour politics. Widely known in journalistic circles, though never reported, his attachment did not outwardly affect his marriage, but it did show the streak of recklessness and the overpowering emotionalism in his character that so diverged from his public image."

In March 1960, Henry Brandon contacted Marion Leiter who arranged for Fleming to have dinner with John F. Kennedy. The author of The Life of Ian Fleming (1966), John Pearson, has pointed out: "During the dinner the talk largely concerned itself with the more arcane aspects of American politics and Fleming was attentive but subdued. But with coffee and the entrance of Castro into the conversation he intervened in his most engaging style. Cuba was already high on the headache list of Washington politicians, and another of those what’s to-be-done conversations got underway. Fleming laughed ironically and began to develop the theme that the United States was making altogether too much fuss about Castro – they were building him into a world figure, inflating him instead of deflating him. It would be perfectly simple to apply one or two ideas which would take all the steam out of the Cuban." Kennedy asked him what would James Bond do about Fidel Castro. Fleming replied, “Ridicule, chiefly.” Kennedy must have passed the message to the CIA for on as the following day Brandon received a phone-call from Allen Dulles, asking for a meeting with Fleming.

Fleming published a collection of short stories, For Your Eyes Only in 1960. Maurice Richardson, writing in Queen Magazine, argued that Fleming's short stories "give you the feeling that Bond's author may be approaching one of those sign-posts in his career and thinking about taking a straighter path."

Ivar Bryce became a film producer and helped to finance The Boy and the Bridge (1959). The film lost money but Bryce decided he wanted to work with its director, Kevin McClory, again and it was suggested that they created a company, Xanadu Films. Fleming, Josephine Hartford and Ernest Cuneo became involved in the project. It was agreed that they would make a movie featuring Fleming's character, James Bond.

The first draft of the script was written by Cuneo. It was called Thunderball and it was sent to Fleming on 28th May. Fleming described it as "first class" with "just the right degree of fantasy". However, he suggested that it was unwise to target the Russians as villains because he thought it possible that the Cold War could be finished by the time the film had been completed. He suggested that Bond should confront SPECTRE, an acronym for the Special Executive for Counterintelligence, Revolution and Espionage. Fleming eventually expanded his observations into a 67-page film treatment. Kevin McClory now employed Jack Whittingham to write a script based on Fleming's ideas.

The Boy and the Bridge was a flop at the box-office and Bryce, on the recommendation of Ernest Cuneo, decided to pull-out of the James Bond film project. McClory refused to accept this decision and on 15th February, 1960, he submitted another version of the Thunderball script by Whittingham. Fleming read the script and incorporated some of the Whittingham's ideas, for example, the airborne hijack of the bomb, into the latest Bond book he was writing. When it was published in 1961, McClory claimed that he discovered eighteen instances where Fleming had drawn on the script to "build up the plot".

Fleming continued to live with Ann Fleming. He wrote to her: "The point lies only in one area. Do we want to go on living together or do we not? In the present twilight we are hurting each other to an extent that makes life hardly bearable." He recorded in his diary: "One of the great sadnesses is the failure to make someone happy." Ann told Cyril Connolly, that Fleming had constantly moaned: "How can I make you happy, when I am so miserable myself?"

In an attempt to make the relationship work they purchased a house in Sevenhampton. His mistress, Blanche Blackwell, moved to England to continue the relationship. Every Thursday morning Blanche would drive him down to Henley where they would have lunch at the Angel Hotel.

President John F. Kennedy was a fan of Fleming's books. In March 1961, Hugh Sidey, published an article in Life Magazine, on President Kennedy's top ten favourite books. It was a list designed to show that Kennedy was both well-read and in tune with popular taste. It included Fleming's From Russia With Love. Up until this time, Fleming's books had not sold well in the United States, but with Kennedy's endorsement, his publishers decided to mount a major advertising campaign to promote his books. By the end of the year Fleming had become the largest-selling thriller writer in the United States.

This publicity resulted in Fleming signed a film deal with the producers, Albert Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, in June 1961. Dr No, starring Sean Connery, opened in the autumn of 1962 and was an immediate box-office success. As soon as it was released Kennedy demanded a showing in his private cinema in the White House. Encouraged by this new interest in his work, Fleming produced another James Bond book, On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1963).

Kevin McClory and Jack Whittingham became angry at the success of the James Bond film and believed that Fleming, Ivar Bryce and Ernest Cuneo had cheated them out of making a profit out of their proposed Thunderball film. The case appeared before the High Court on 20th November 1963. Three days into the case, when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. McClory's solicitor, Peter Carter-Ruck, later recalled: "The hearing was unexpectedly and somewhat dramatically adjourned after leading counsel on both sides had seen the judge in his private rooms." Bryce agreed to pay the costs, and undisclosed damages. McClory was awarded all literary and film rights in the screenplay and Fleming was forced to acknowledge that his novel was "based on a screen treatment by Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham and the author."

On this day in 1976 journalist and politician Tom Driberg died of a heart-attack. His autobiography, Ruling Passions, was published posthumously in 1977.

Tom Driberg was born at Crowborough, East Sussex, on 22nd May 1905. His father, John Driberg, worked for the Indian Civil Service. Educated at Lancing College, Driberg joined the Communist Party when he was fifteen.

Driberg went to Christ Church, Oxford, and studied classics (1924-27) but left without graduating.

During the General Strike Driberg worked at party headquarters and began writing for the communist newspaper, Sunday Worker.

In 1928 he joined the Daily Express as a gossip columnist. He came to the attention of Lord Beaverbrook who gave him his own column "These Names Makes News". It was at this time that Driberg began using the pen name, William Hickey, a famous 18th century diarist.

Driberg was a strong opponent of the British government's Non-Intervention policy in the Spanish Civil War. He visited Spain as a journalist during the war. In January 1939, he helped to take food supplies to the Republican Army fighting General Francisco Franco and his nationalist forces.

Maxwell Knight, head of B5b, a unit that conducted the monitoring of political subversion, recruited Driberg as an agent for MI5. In 1941 Anthony Blunt informed Harry Pollitt that Driberg was an informer and he was expelled from the Communist Party. Knight now suspected that his unit had been infiltrated by the KGB but it was not until after the war that MI5 discovered that Blunt was responsible for exposing Driberg.

In 1942 he was elected to the House of Commons at the Maldon by-election as an Independent. In 1943 Driberg was dismissed from the Daily Express and transferred to the Reynold's News. He later wrote for the Daily Mail and the New Statesman.

During the Second World War Driberg joined the Labour Party and in 1945 retained his seat in Parliament. In 1949 he was elected to the party's National Executive but he was severely censured in 1950 for gross neglect of his parliamentary duties by taking three months off to report on the Korean War.

In his book, Spycatcher (1987), Peter Wright, who had previously worked for MI5 claimed: "Since the 1960s a wealth of material about the penetration of the latter two bodies had been flowing into MI5's files, principally from two Czechoslovakian defectors named Frolik and August. They named a series of Labour Party politicians and trade union leaders as Eastern Bloc agents... Tom Driberg was another MP named by the Czech defectors. I went to see Driberg myself, and he finally admitted that he was providing material to a Czech controller for money. For a while we ran Driberg on, but apart from picking up a mass of salacious detail about Labour Party peccadilloes, he had nothing of interest for us."

Tom Driberg was commissioned to write a book on Soviet spy, Guy Burgess, who he become friendly with in the 1940s. During his research for the book Driberg travelled to Moscow to interview Burgess. He later remarked: "He (Burgess) had lately moved into a new flat in Moscow, for which I had sent him a good deal of Scandinavian furniture from London, and I was able to spend a weekend at his dacha, in a country village about an hour's drive (by official pool car)."

Both Driberg and Burgess were homosexuals and it seems that they had some sort of sexual relationship while in the Soviet Union. According to the Mitrokhin Archive, Driberg was photographed in a homosexual encounter. The honeytrap operation was an attempt to force Driberg to spy for the KGB. The book, Guy Burgess, A Portrait with Background, was published in 1956.Tom Driberg served as chairman of the Labour Party National Executive in 1957-58. After losing Maldon in 1958 Driberg moved to Barking which he won in 1959.

In the early 1960s Driberg attended sex parties with Lord Boothby in London. Boothby commented in its autobiography, Boothby: Recollections of a Rebel: "Tom Driberg once told me that sex was only enjoyable with someone you had never met before, and would never meet again." Winston Churchill added that "Tom Driberg is the sort of person who gives sodomy a bad name."

According to the journalist, John Pearson, "Driberg got to know them through Mad Teddy Smith, a good-looking psychopathic gangster who was a friend and occasional enemy of the Krays. Driberg, described as a voracious homosexual, is said to have given Smith the addresses of his rich acquaintances, whose houses he might burgle in return for sexual favours." As a result of these sex parties Boothby began an affair with gangster Ronnie Kray.

In June 1964, two Conservative back-benchers reported to the chief whip that they had seen Driberg and Lord Boothby at a dog track importuning boys. Boothby was on holiday with Colin Coote, the editor of the Daily Telegraph, when on 12 July 1964, the Sunday Mirror published a front page lead story under the headline: "Peer and a gangster: Yard probe." The newspaper claimed police were investigating an alleged homosexual relationship between a "prominent peer and a leading thug in the London underworld", who is alleged to be involved in a West End protection racket.

The following week the newspaper said it had a picture of the peer and the gangster sitting on a sofa. Rumours soon began circulating that the peer was Lord Boothby and the gangster was Ronnie Kray. Stories also circulated that Harold Wilson and Cecil King, the chairman of the International Publishing Corporation were conspiring in an attempt to overthrow the Conservative government led by Alec Douglas -Home. Boothby's friend, Colin Coote used his contacts in the media to discover what was going on.

As journalist John Pearson pointed out: "By doing nothing he (Boothby) would tacitly accept the Sunday Mirror's accusations. On the other hand, to sue for libel would mean facing lengthy and expensive court proceedings which could ruin him financially - apart from whatever revelations the Sunday Mirror could produce to support its story." Boothby was then approached by two leading Labour Party figures, Gerald Gardiner, QC and solicitor Arnold Goodman. They offered to represent Lord Boothby in any libel case against the newspaper. Goodman was Wilson's "Mr Fixit" and Gardiner was later that year to become the new prime-minister's Lord Chancellor.

John Pearson has argued that Driberg was behind this cover-up: "As an important member of the Labour executive, Driberg had a lot of influence, particularly over Harold Wilson, and he would certainly have used it to encourage Arnold Goodman's rescue operation which would save Boothby and himself. All of which undoubtedly explains why, after the settlement, there was not a squeak in parliament about the case - and why instead there seemed an overwhelming cross-bench willingness to let sleeping dogs, however dirty, lie - and go on lying."

Tom Driberg left the House of Commons in 1974 and the following year was created Baron Bradwell.