On this day on 4th August

On this day in 1792 Percy Bysshe Shelley, the son of Sir Timothy Shelley, the M.P. for New Shoreham, was born at Field Place near Horsham, in 1792. Sir Timothy Shelley sat for a seat under the control of the Duke of Norfolk and supported his patron's policies of electoral reform and Catholic Emancipation.

Shelley was educated at Eton and Oxford University and it was assumed that when he was twenty-one he would inherit his father's seat in Parliament. As a young man he was taken to the House of Commons where he met Sir Francis Burdett, the Radical M.P. for Westminster. Shelley, who had developed a strong hatred of tyranny while at Eton, was impressed by Burdett, and in 1810 dedicated one of his first poems to him. At university Shelley began reading books by radical political writers such as Tom Paine and William Godwin.

At university Shelley wrote articles defending Daniel Isaac Eaton, a bookseller charged with selling books by Tom Paine and the much persecuted Radical publisher, Richard Carlile. He also wrote The Necessity of Atheism, a pamphlet that attacked the idea of compulsory Christianity. Oxford University was shocked when they discovered what Shelley had written and on 25th March, 1811 he was expelled.

Shelley eloped to Scotland with Harriet Westbrook, a sixteen year old daughter of a coffee-house keeper. This created a terrible scandal and Shelley's father never forgave him for what he had done. Shelley moved to Ireland where he made revolutionary speeches on religion and politics. He also wrote a political pamphlet A Declaration of Rights, on the subject of the French Revolution, but it was considered to be too radical for distribution in Britain.

Percy Bysshe Shelley returned to England where he became involved in radical politics. He met William Godwin the husband of Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of Vindication of the Rights of Women. Shelley also renewed his friendship with Leigh Hunt, the young editor of The Examiner. Shelley helped to support Leigh Hunt financially when he was imprisoned for an article he published on the Prince Regent.

Leigh Hunt published Queen Mab, a long poem by Shelley celebrating the merits of republicanism, atheism, vegetarianism and free love. Shelley also wrote articles for The Examiner on polical subjects including an attack on the way the government had used the agent provocateur William Oliver to obtain convictions against Jeremiah Brandreth.

In 1814 Shelley fell in love and eloped with Mary, the sixteen-year-old daughter of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. For the next few years the couple travelled in Europe. Shelley continued to be involved in politics and in 1817 wrote the pamphlet A Proposal for Putting Reform to the Vote Throughout the United Kingdom. In the pamphlet Shelley suggested a national referendum on electoral reform and improvements in working class education.

Percy Bysshe Shelley was in Italy when he heard the news of the Peterloo Massacre. He immediately responded by writing The Mask of Anarchy, a poem that blamed Lord Castlereagh, Lord Sidmouth and Lord Eldon for the deaths at St. Peter's Fields. In The Call to Freedom Shelley ended his argument for non-violent mass political protest with the words: "Which in sleep had fallen on you - Ye are many - they are few."

In 1822 Percy Bysshe Shelley, moved to Italy with Leigh Hunt and Lord Byron where they published the journal The Liberal. By publishing it in Italy the three men remained free from prosecution by the British authorities. The first edition of The Liberal sold 4,000 copies. Soon after its publication, Percy Bysshe Shelley was lost at sea on 8th July, 1822 while sailing to meet Leigh Hunt.

On this day in 1840 Lord Ashley makes speech in the House of Commons on child labour. "The future hopes of a country must, under God, be laid in the character and condition of its children; however right it may be to attempt, it is almost fruitless to expect, the reformation of its adults; as the sapling has been bent, so will it grow. The first step towards a cure is factory legislation. My grand object is to bring these children within the reach of education."

On this day in 1869 Evelyn Sharp, the ninth of eleven children, was born on 4th August 1869. Her father, James Sharp, was a slate merchant. Her brother, Cecil Sharp (1859-1924), later gained fame as the leader of the folk-dance revival. Evelyn only had a couple of years of conventional schooling, but successfully passed several university local examinations.

In 1881 Evelyn Sharp, aged twelve, was sent to Strathallan House School. She enjoyed boarding school: "School was the great adventure of late Victorian girlhood, where girls for the first time found their own level." Sharp was an intelligent girl and passed the Cambridge Higher Local Examination in history. Whereas her brothers went to the University of Cambridge, she was sent to a finishing school in Paris.

Against the wishes of her family, Sharp moved to London where she undertook daily tutoring while writing articles for the Pall Mall Gazette and the girls' magazine, Atalanta. She later claimed that a writer should approach children as equals and "make them feel on a level with the author". Sharp also wrote and published several novels including, The Making of a Prig (1897), All the Way to Fairyland (1898) and The Other Side of the Sun (1900).

On 30th December 1901, Evelyn Sharp met Henry Nevinson for the first time at the Prince's Ice Rink in Knightsbridge. She later recalled, "when he took my hand in his and we skated off together as if all our life before had been a preparation for that moment." Although he was married to Margaret Nevinson, they soon became lovers. Nevinson wrote in his diary that Evelyn "was both pretty and wise - exquisite in every way". Evelyn later told him: "The first time I saw you I knew you wanted something you have never got." The situation was further complicated by the fact that Nevinson was also having an affair with Nannie Dryhurst.

Nevinson, who was an experienced journalist, helped her to find work writing articles for the Daily Chronicle and the Manchester Guardian, a newspaper that published her work for over thirty years. Sharp's journalism made her more aware of the problems of working-class women and she joined the Women's Industrial Council and the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. Sharp and Nevinson shared the same political beliefs. He told his old friend from university, Philip Webb, that Evelyn possessed "a peculiar humour, unexpected, stringent, keen without poison" but "above all she is a supreme rebel against injustice.

Evelyn Sharp worked as a journalist and a part-time teacher. In November, 1903, her father died: "I went to Brook Green to live for the best part of a year with my mother... By the time I was free again I had lost my teaching connection, and, rather than attempt to work it up again, I determined to rely instead on journalism for my regular income. I was equally sorry to give up my private pupils and my school lecturing, which not only interested me but also brought me into contact with children at a period when I was writing stories about them. At the same time, I have never regretted a change which caused me seriously to adopt a great profession and led to many journeys and adventures that would not otherwise have come my way."

In 1905 Sharp and Nevinson established the Saturday Walking Club. Other members included William Haselden, Henry Hamilton Fyfe, Clarence Rook and Charles Lewis Hind. According to Angela V. John, the author of Evelyn Sharp: Rebel Women (2009): "Although Evelyn and Henry were serious walkers, both the Saturday Walking Club and dining with friends afforded the opportunity to be together in public in a manner that was acceptable."

In May 1906 she told Nevinson that she would give up all her literary fame to "belong to you openly and fairly." The following month she wrote to Nevinson: "If it isn't true that you love me it isn't true that the sun shines or that my heart beats quicker when I hear you at the door. My heart is only ill because you put a smile into it that will never die, and my heart had not learnt to smile before." Evelyn Sharp was desperate to have children, but as Nevinson remained married this was impossible. She told a friend that she knew that she was "longing for the impossible" and that "I can hardly bear to look at a baby now."

In the autumn of 1906 Sharp was sent by the Manchester Guardian to cover a speech by Elizabeth Robins. She later wrote: "Elizabeth Robins, then at the height of her fame both as a novelist and as an actress, sent a stir through the audience when she stepped on the platform. The impression she made was profound, even on an audience predisposed to be hostile; and on me it was disastrous. From that moment I was not to know again for twelve years, if indeed ever again, what it meant to cease from mental strife; and I soon came to see with a horrible clarity why I had always hitherto shunned causes."

As a result of hearing the speech, Sharp joined the the Women's Social and Political Union. Sharp later recalled the differences between the suffragists (NUWSS) and the suffragettes (WSPU). Suffragists had waited and worked for so long that they felt they could wait a little longer. Suffragettes who had become "suddenly aware of an imperative need, could not wait another minute."

Evelyn Sharp made her first WSPU speech at Fulham Town Hall in January 1907. In her autobiography, Unfinished Adventure, Sharp admitted that she was terrified by public speaking and that it caused a "cold feeling at the pit of the stomach". However, she used humour to disarm her audience and Emmeline Pankhurst claimed that she was one of the WSPU's best speakers. She went on a WSPU demonstration with Henry Nevinson on 13th February 1907. He recorded that after being attacked by a police officer he resorted to language that was "something horrible."

In 1907 Sharp began a regular column on women's suffrage for the Daily Chronicle. However, in November the editor decided to stop the articles because they "alienated" so many readers. C. P. Scott, her editor at the Manchester Guardian, disapproved of the WSPU's tactics but admitted that Sharp was "the ablest and best brain in the movement".

In January 1909 Sharp was sent to Denmark to lecture on the militant suffrage movement. The following year she was appointed as secretary for the Kensington branch of the WSPU. Another member was the surgeon Louisa Garrett Anderson and the two women became very close friends. The two women sold Votes for Women in Kensington High Street.

Sharp also published Rebel Women (1910), a series of vignettes of suffrage life. Angela V. John, the author of Evelyn Sharp: Rebel Women (2009), has argued: "It brought together in fourteen revealing vignettes the mundane, yet extraordinary, lives of suffragettes. Evelyn tells tales of the unexpected. we see a working-class mother and lady writer making common cause and a little rebel who seizes the moment to join the boys in her own version of cricket. The stories warn us never to jump to conclusions or judge people by appearance."

Evelyn's mother was unhappy about her daughter being a member of the WSPU and made her promise not to do anything that would result in her being sent to prison. In a letter on 25th March 1911, her mother absolved her from that promise: "I am writing to exonerate you from the promise you made me - as regards being arrested - although I hope you will never go to prison, still I feel I cannot any longer be so prejudiced and must really leave it to your own better judgment. So brave, so enthusiastic as you have been for so long - I have really been very unhappy about it and feel I have no right to thwart you - much as I should regret feeling that you were undergoing those terrible hardships which so many noble and brave women have and are doing still... I feel sure what a grief it has been that you could not accompany your friends: I cannot write more but you will be happy now, won't you?"

Evelyn Sharp now became active in the militant campaign. On 7th November she was sent to Holloway Prison for fourteen days for breaking government windows. In her autobiography, Unfinished Adventure, she explained what happened when she arrived in prison: "When the doctor asked me if I minded solitary confinement, I surprised him by saying truly that I objected to it because it was not solitary. You might be left alone for twenty-two out of twenty-four hours, but you could never be sure of being left for five minutes without the door being burst suddenly open to admit some official. Yet this threat of interruption, while it destroyed solitude, which I love, never took me from the horror of the locked door, just as one never lost the irritating sense of being peered at through the observation hole."

On 22nd November Evelyn Sharp wrote from her prison cell: "Just by sitting here with cold feet and being given suet pudding (without treacle) for dinner, and going without a bath, and being treated like rather a dangerous child - one is doing more for the cause than all the eloquence of the last five years." However, later Sharp admitted that she felt uncomfortable about taking militant action: "Who am I to be doing all these ugly things when I only long for solitude and a fairy tale to write.... I only know I shall go on till I drop and so will hundreds of others whose names will never be known."

On 5th March 1912, detectives arrived at the WSPU headquarters at Clement's Inn to arrest Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick Lawrence. It was the Pethick-Lawrences who edited and financed the WSPU's newspaper, Votes for Women. As Angela V. John has pointed out: "Frederick Pethick Lawrence believed that Evelyn was the one person with the requisite technical experience and political acumen to take over the paper as assistant editor - it was just twenty-four hours away from going to press - and this she agreed to do." Elizabeth Robins has argued that the newspaper now had an editor of "distinguished ability and rare devotion."

Sharp was also an active member of the Women Writers Suffrage League and on 24th August 1913 she was chosen to represent the organisation in a delegation that hoped to meet with the Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna, at the House of Commons to discuss the Cat and Mouse Act. McKenna was unwilling to talk to them and when the women refused to leave the building, Mary Macarthur and Margaret McMillan were physically ejected and Sharp, Sybil Smith and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were arrested and sent to Holloway Prison.

The arrest of Sybil Smith, the daughter of the William Randal McDonnell, 6th Earl of Antrim, and the mother of seven children, created problems for the government and Sharp and the other suffragettes were released unconditionally after four days. Henry Nevinson arrived at the prison gates with red roses and a bottle of Muscat. He wrote in his diary that they "had perfect happiness again". Weighing less than seven stone she was taken to the home of Hertha Ayrton where she was looked after by her doctor friend, Louisa Garrett Anderson. A few days later she spent time in the Oxfordshire home of Gerald Gould and Barbara Ayrton Gould.

Sharp continued to be involved with Henry Nevinson. As he was a foreign correspondent he was often out of the country. When he was away she wrote him passionate love letters. On one occasion she said: "Oh I am so glad I love some one who could never make me feel ashamed of what I have given so freely." Women found Henry Nevinson very attractive. Henry Brailsford has argued that "Nevinson was a handsome man, who carried himself with a noble air which earned him the nickname of the Grand Duke. His blend of humanity, compassion, and daring made him a popular figure in his own lifetime." Olive Banks commented: "He obviously admired the courage and determination of the militant leaders. At heart a romantic, his view of women was not without its protective side, and female beauty had a strong appeal to him. On the other hand, his passion for freedom, which inspired so much of his work, gave him sympathy also for women's need for political rights and self-determination."

Angela V. John has argued that: "He was cultured and courteous yet rebellious. He travelled to faraway and dangerous places. A touch of shyness, an ability to listen to others and an appreciation of women's rights and of intelligent women ensured that many found him irresistible." Evelyn Sharp also made a big impression on Nevinson. In 1913 he wrote to Sidney Webb: "She (Sharp) has one of the most beautiful minds I know - always going full gallop, as you see from her eyes, but very often in regions beyond the moon, when it takes a few seconds to return. At times she is the very best speaker among the suffragettes."

Sharp left the Women's Social and Political Union in protest against the expulsion by Emmeline Pankhurst of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick Lawrence. The breakaway group formed the United Suffragists and Sharp edited its journal, Votes for Women. Other members of this organisation included Henry Nevinson, Margaret Nevinson, Hertha Ayrton, Israel Zangwill, Edith Zangwill, Lena Ashwell, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, John Scurr, Julia Scurr and Laurence Housman.

Unlike many members of the women's movement, Sharp was unwilling to end the campaign for the vote during the First World War. This brought her criticism from the leaders of the WSPU. In 1914 Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." In

October 1915, the WSPU changed its newspaper's name from The Suffragette to Britannia. Emmeline's patriotic view of the war was reflected in the paper's new slogan: "For King, For Country, for Freedom'. In the newspaper anti-war activists such as Ramsay MacDonald were attacked as being "more German than the Germans".

Her friend and fellow campaigner for women's suffrage, Beatrice Harraden, objected to the unpatriotic tone of some of her articles in Votes for Women. Evelyn was also asked by C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian, to modify the pacifist tone of some of her stories that were published in the newspaper during the war.

During the First World War a group of wealthy suffragettes, including Janie Allan, decided to fund the Women's Hospital Corps. Evelyn Sharp did support this venture and she visited Louisa Garrett Anderson and Flora Murray when they were running the hospital in Claridge Hotel in Paris.

A pacifist, Sharp was active in the Women's International League for Peace that was established soon after the war started. She was one of 156 British women invited to its conference in The Hague in April 1915. Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary, refused permission for the women to go. Only Chrystal Macmillan, Kathleen Courtney and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, who had already left the country, managed to attend the conference.

Sharp was also a member of the Tax Resistance League and refused to pay income tax on her earnings. She argued that to do so amounted to "taxation without representation". By 1917 she owed six years' tax and the authorities declared her bankrupt. Her possessions were seized and sold at public auction. Her friends came to her aid and purchased items that they later gave back to her.

On 10th January 1918, a majority in the House of Lords, voted for the Qualification of Women Act. Evelyn Sharp wrote that later that night she walked around the scenes of their long fought battle. It "was almost the happiest moment of my life" when "I walked away up Whitehall on the evening that the lost cause triumphed." Two days later Henry Nevinson hosted a dinner in honour of the victory. Guests included Sharp, Elizabeth Robins, J. A. Hobson, Gerald Gould and Barbara Ayrton Gould.

Nevinson later argued that the persistence of the United Suffragists that had made the triumph of 1918 possible. He added that all its members would admit that our very existence through those four years from February 1914 to February 1918, were almost entirely due to the brilliant mind and dogged resolution of Evelyn Sharp, who inspired our members to maintain their enthusiasm."

After the Armistice, Evelyn Sharp, now a member of the Labour Party, worked as a journalist for a variety of newspapers, including the Daily Herald and the Manchester Guardian. She visited Russia several times. In November, 1917, she had written in her diary that she was "thrilled at the news of the Russian Revolution". In an article published in The Nation in 1919, Sharp argued that the Bolsheviks were creating a society "in which no one shall starve, and no able-bodied person shall be idle". She added that communism was "the most magnificent ideal of life ever conceived." However, Sharp never joined the Communist Party of Great Britain and by the early 1920s she had become totally disillusioned by the repressive measures of the Soviet government.

In May 1922 the Manchester Guardian started a daily Women's Page. Edited by Madeline Linford, it dealt with "subjects which are special to women" and aimed at the "intelligent woman". Evelyn Sharp was its first regular columnist. Other contributors included Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby. As Angela V. John has pointed out: "It became renowned, provoking debates about the necessity for space dedicated to women."

Henry Nevinson and Margaret Nevinson still lived together. They used to eat separately except for Sundays. According to her biographer, Angela V. John: "Her final years were lonely ones, plagued by depression." Christopher Nevinson described their home "a cheerless uninhabited house". Henry wrote: "Children are a quiverful of arrows that pierce the parents' hearts."

In 1928 Margaret told friends that she wanted to go into a nursing home "and have done with it". She tried to drown herself in the bath. Henry Nevinson wrote to Elizabeth Robins about her health: "At present I am in great tribulation, for Mrs. Nevinson's mind is rapidly failing, and I am perplexed what is best for her. To send her to a mental home among strangers seems to me cruel, but all are urging it, partly in hopes of reducing the great expense. I am so much opposed to it that I should far rather go on spending my small savings in the hope that she may end quietly here." Margaret Nevinson died of kidney failure at her Hampstead home, 4 Downside Crescent, on 8th June 1932.

Henry Nevinson married Evelyn Sharpon 18th January 1933 at Hampstead Registry Office. Evelyn was 63 and Henry was in his seventy-seventh year. Evelyn wrote that "if age and experience have any value at all, they should help and not hinder the explorer who sets out to sail the uncharted seas of married life." The prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, offered to be best man but they refused as they had not approved of him becoming the leader of the National Government. Evelyn shocked the guests by wearing a black dress for the ceremony. Sharp's autobiography, Unfinished Adventure, was published later that year.

Soon after the outbreak of the Second World War the Nevinsons' house in Hampstead was bombed and in October 1940 the couple moved to the vicarage at Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire. Henry Nevinson died aged 85 on 9th November, 1941. Sharp wrote in her diary: "There was a flaming red sunset right across the sky and the reflection of it was across the room."

Margaret Storm Jameson told Evelyn that "you were woven into his life by memories, going back years and years" and that he had depended on her "as an anchor and centre". Maude Royden claimed that Evelyn and Henry's "happiness had lit up a room like a lamp". George Peabody Gooch added that the "greatest thing in his life was their love for each other".

Evelyn returned to living alone in London flats as she had done for most of her adult life. She died in Methuen Nursing Home, 13 Gunnersbury Avenue, Ealing, on 17 June 1955. During her life she had published over thirty books including fifteen novels, several volumes of short stories, the libretto for an opera by Ralph Vaughan Williams, a history of folk dancing and a life of the physicist Hertha Ayrton.

On this day in 1878 Flora Gibson was born in Manchester, but spent her childhood on the Isle of Arran. She took a business training course in Glasgow and also attended lectures on economics at the University of Glasgow. Flora qualified as a post mistress but was refused entry because she was too short.

After her marriage to Joseph Drummond in 1898 Flora lived in Manchester and she and her husband joined the Independent Labour Party. She was also a member of the Fabian Society and the Clarion Club. Her husband worked as an upholsterer. At the time she was employed in a baby-linen factory.

According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "Flora Drummond... later explained her involvement in the women's suffrage movement by her experience at this time. She saw that women were paid such low wages that they were forced to engage in prostitution in order to live. Flora Drummond's husband, an upholsterer, was often out of work and it seems unlikely that she would have elected to take low-paid work if she could have been more gainfully employed."

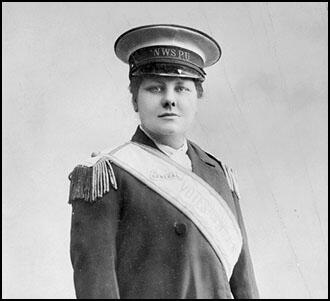

Flora Drummond became a member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and in the summer of 1905 she joined Hannah Mitchell in the campaign to recruit women to the cause in Lancashire towns. On 13th October she was with Teresa Billington-Greig at the Free Trade Hall when they witnessed the arrests of Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney. Pankhurst and Kenney were found guilty of assault and fined five shillings each. When the women refused to pay the fine they were sent to prison.

In 1906 Drummond joined Annie Kenney, Mary Gawthorpe, Nellie Martel, Helen Fraser, Adela Pankhurst and Minnie Baldock as WSPU full-time organizers. As Christabel Pankhurst pointed out: "Clement's Inn, our headquarters, was a hive seething with activity... General Flora Drummond's office was full of movement. As department was added to department, Clement's Inn seemed always to have one more room to offer. Mary Richardson described her as having a "broad, lovable Scottish accent."

On 9th March, 1906, Flora Drummond and Annie Kenney, led a demonstration to Downing Street, repeatedly knocking on the door of the Prime Minister, Henry Campbell-Bannerman. Drummond and Kenney were arrested but Campbell-Bannerman refused to press charges and they were released. A few months later Drummond was arrested outside the House of Commons and she served her first term of imprisonment in Holloway Prison.

In 1908 Flora Drummond was put in charge of the WSPU offices at Clement's Inn. It was during this time that she acquired the nickname "General". Emmeline Pankhurst said that "Mrs. Drummond is a woman of very great public spirit; she is an admirable wife and mother; she has very great business ability, and she has maintained herself, although a married woman, for many years, and has acquired for herself the admiration and respect of all the people with whom she has had business relations."

Flora Drummond was arrested with Christabel Pankhurst in October 1908 and charged with the incitement to "rush the House of Commons". She was sentenced to three months' imprisonment but she was discharged after nine days, when the prison authorities discovered that she was pregnant. Her son was named "Keir" after Keir Hardie.

In 1909 Drummond moved to Glasgow. She wrote to Minnie Baldock that her husband, Joseph Drummond, had decided to go and live in Australia. She organized the WSPU campaign in the January 1910 General Election. In 1911 she returned to Clement's Inn where she was put in charge of all the WSPU branches in the country on a wage of £3 10s a week.

Drummond was arrested during a demonstration on 15th April 1913. In court she argued that if she was imprisoned she would go on hunger-strike. The Daily Herald reported: "She (Flora Drummond) did not like the idea of hunger striking any more than the most normal human beings, but hunger strike she would if she were sent to gaol." The court decided to withdraw the charges against her.

In May 1914, she was arrested again. For the ninth time she was imprisoned. After going on hunger strike she was released under the Cat and Mouse Act. Drummond recuperated in the Isle of Arran but she returned to Clement's Inn after the outbreak of the First World War. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

During the First World War Drummond toured the country in an attempt to persuade trade unionists from going on strike. In 1917 Drummond joined with Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst to form the The Women's Party. Its twelve-point programme included: (1) A fight to the finish with Germany. (2) More vigorous war measures to include drastic food rationing, more communal kitchens to reduce waste, and the closing down of nonessential industries to release labour for work on the land and in the factories. (3) A clean sweep of all officials of enemy blood or connections from Government departments. Stringent peace terms to include the dismemberment of the Hapsburg Empire." The WP also supported: "equal pay for equal work, equal marriage and divorce laws, the same rights over children for both parents, equality of rights and opportunities in public service, and a system of maternity benefits." Christabel and Emmeline had now completely abandoned their earlier socialist beliefs and advocated policies such as the abolition of the trade unions.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918, Flora Drummond helped Christabel Pankhurst, who represented the The Women's Party in Smethwick. Despite the fact that the Conservative Party candidate agreed to stand down, Christabel lost a straight fight with the representative of the Labour Party by 775 votes.

In 1922 Flora divorced Joseph Drummond and two years later married Alan Simpson, an engineer from Glasgow. Drummond had now completely rejected her early socialism and now held right-wing opinions and along with Elsie Bowerman and Norah Dacre Fox established the Women's Guild of Empire, a right wing league opposed to communism. Her biographer, Krista Cowman, pointed out: "When the war ended she was one of the few former suffragettes who attempted to continue the popular, jingoistic campaigning which the WSPU had followed from 1914 to 1918. With Elsie Bowerman, another former suffragette, she founded the Women's Guild of Empire, an organization aimed at furthering a sense of patriotism in working-class women and defeating such socialist manifestations as strikes and lock-outs." By 1925 Drummond claimed the organization had a membership of 40,000. In April 1926, she led a demonstration that demanded an end to the industrial unrest that was about to culminate in the General Strike.

Juanita Frances, who worked with Drummond in the Women's Guild of Empire, described her as someone who "looked as she spoke" and was "like a charwoman" and that she was "rather shabby" and "a little unkempt".

Drummond became involved in a dispute with Norah Dacre Fox who had criticised the violent methods of the British Union of Fascists. On 22nd February 1935 Norah argued in The Blackshirt that Drummond had once "defied all law and order; smashed not only windows, but all the meetings of Cabinet Ministers on which she could lay hands, and was for long the daily terror of the Public Prosecutor and the despair of Bow Street!" Norah described Drummond and other former suffragettes as "extinct volcanoes either wandering about in the backwoods of international pacifism and decadence, or prostrating themselves before the various political parties."

Flora Drummond died on 17th January 1949.

On this day in 1914 Karl Liebknecht was the only member of the Reichstag who voted against Germany's participation in the First World War. He argued: "This war, which none of the peoples involved desired, was not started for the benefit of the German or of any other people. It is an Imperialist war, a war for capitalist domination of the world markets and for the political domination of the important countries in the interest of industrial and financial capitalism. Arising out of the armament race, it is a preventative war provoked by the German and Austrian war parties in the obscurity of semi-absolutism and of secret diplomacy."

Paul Frölich, a supporter of Liebknecht in the Social Democratic Party (SDP), argued: "On the day of the vote only one man was left: Karl Liebknecht. Perhaps that was a good thing. That only one man, one single person, let it be known on a rostrum being watched by the whole world that he was opposed to the general war madness and the omnipotence of the state - this was a luminous demonstration of what really mattered at the moment: the engagement of one's whole personality in the struggle. Liebknecht's name became a symbol, a battle-cry heard above the trenches, its echoes growing louder and louder above the world-wide clash of arms and arousing many thousands of fighters against the world slaughter."

John Peter Nettl claims that two left-wing members of the SDP, Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin, were horrified by these events. They had great hopes that the SDP, the largest socialist party in the world with over a million members, would oppose the war: "Both Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin suffered nervous prostration and were at one moment near to suicide. Together they tried on 2 and 3 August to plan an agitation against the war; they contacted 20 SPD members with known radical views, but they got the support of only Liebknecht and Mehring... Rosa sent 300 telegrams to local officials who were thought to be oppositional, asking their attitude to the vote in the Reichstag and inviting them to Berlin for an urgent conference. The results were pitiful."

Karl Liebknecht campaigned against the war but decided against forming a new party and agreed to continue working within the SPD. Clara Zetkin was initially reluctant to join this anti-war faction. She argued: "We must ensure the broadest relationship with the masses. In the given situation the protest appears more as a personal beau geste than a political action... It is justified and nice to say that everything is lost, except one's honour. If I wanted to follow my feelings, then I would have telegraphed a yes with great pleasure. But now we must more than ever think and act coolly."

However, by September, 1914, Zetkin was playing a significant role in the anti-war movement. She co-signed with Luxemburg, Liebknecht and Mehring, letters that appeared in socialist newspapers in neutral countries condemning the war. Above all Zetkin used her position as editor-in-chief of the Glieichheit and as Secretary of the Women's Secretariat of the Socialist International to propagate the positions of the anti-war movement.

Clara Zetkin who later recalled: "The struggle was supposed to begin with a protest against the voting of war credits by the social-democratic Reichstag deputies, but it had to be conducted in such a way that it would be throttled by the cunning tricks of the military authorities and the censorship. Moreover, and above all, the significance of such a protest would doubtless be enhanced, if it was supported from the outset by a goodly number of well-known social-democratic militants."

Karl Liebknecht continued to make speeches in public about the war: "The war is not being waged for the benefit of the German or any other peoples. It is an imperialist war, a war over the capitalist domination of the world market... The slogan 'against Tsarism' is being used - just as the French and British slogan 'against militarism' - to mobilise the noble sentiments, the revolutionary traditions and the hopes of the people for the national hatred of other peoples."

In May 1915, Liebknecht published a pamphlet, The Main Enemy Is At Home! He argued that: "The main enemy of the German people is in Germany: German imperialism, the German war party, German secret diplomacy. This enemy at home must be fought by the German people in a political struggle, cooperating with the proletariat of other countries whose struggle is against their own imperialists. We think as one with the German people – we have nothing in common with the German Tirpitzes and Falkenhayns, with the German government of political oppression and social enslavement. Nothing for them, everything for the German people. Everything for the international proletariat, for the sake of the German proletariat and downtrodden humanity."

In December, 1915, 19 other deputies joined Karl Liebknecht in voting against war credits. The following year a series of demonstrations took place. Some of these were "spontaneous outbursts by unorganised groups of people, usually women: anger would flare when a shop ran out of food, or put its prices up, or when rations were suddenly cut." These demonstrations often led to bitter clashes between workers and the police.

Over the next few months members of this group were arrested for their anti-war activities and spent several short spells in prison. This included Rosa Luxemburg, Ernest Meyer, Wilhelm Pieck and Hugo Eberlein. Other activists included Leo Jogiches, Paul Levi, Franz Mehring, Julian Marchlewski and Hermann Duncker. On the release of Luxemburg in February 1916, it was decided to establish an underground political organization called Spartakusbund (Spartacus League). The Spartacus League publicized its views in its illegal newspaper, Spartakusbriefe. Like the Bolsheviks in Russia, they argued that socialists should turn this nationalist conflict into a revolutionary war.

On this day in 1917 Noel Chavasse was badly wounded at Passchendaele. Chavasse was sent to the Casualty Clearing Station at Brandhoek. Although operated on he died. Noel Godfrey Chavasse was Britain's most highly decorated serviceman in the war.

Noel Godfrey Chavasse was born in Oxford on 9th November, 1884. His father, Francis Chavasse, became Bishop of Liverpool in 1900.

Chavasse was educated at Liverpool College and Trinity College, Oxford . After graduating with first class honours in 1907 he studied medicine. In 1908 Chavasse and his twin brother, Christopher, both represented Britain in the Olympic Games in the 400 metres.

In 1909 Chavasse joined the Oxford University Officer Training Corps Medical Unit. The following year he sat and passed the examination that allowed him to join the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons. Chavasse worked in Dublin and the Royal Southern Hospital in Liverpool before joining the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1913.

On the outbreak of the First World War Chavasse offered to serve in France. He was transferred to the Western Front in November 1914 where he was attached to the Liverpool Scottish Regiment. In the first few months Chavasse was kept busy dealing with trench foot, a condition caused by standing for long periods in mud and water.

In March 1915 the regiment took part in the offensive at Ypres, where poison gas was used for the first time. By June 1915 only 142 men out of the 829 men who arrived with Chavasse remained on active duty. The rest had been killed or badly wounded.

Chavasse was promoted to captain in August 1915 and six months later was awarded the Military Cross for his actions at the Battle of Hooge. In April 1916 he was granted three days leave to receive his award from King George V.

In July 1916 Chavasse's battalion was moved to the Somme battlefield near Mametz. On the 7th August the Liverpool Scottish Regiment were ordered to attack Guillemont. Of the 620 men who took part in the offensive, 106 of the men were killed and 174 were wounded. This included Chavasse who was hit by shell splinters while rescuing men in no-mans-land. For this he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

In February 1917 he was granted 14 days leave in England. He returned to the Liverpool Scottish Regiment and took part in the offensive at Passchendaele. For nearly two days he went out into the battlefield rescuing and treating wounded soldiers. It was during this period Noel performed the deeds that gained him his second Victoria Cross.