Women's Industrial Council

In 1886 Clementina Black and Eleanor Marx, both became active in the Women's Trade Union League. For the next few years they travelled the country making speeches trying to persuade women to join trade unions and to campaign for "equal pay for equal work".

In 1889 Clementina Black helped form the Women's Trade Union Association. Five years later she merged this organisation with the Women's Industrial Council. Clementina became president of the council and for the next twenty years she was involved in collecting and publicizing information on women's work. Other members included Margaret Gladstone, Hilda Martindale, Charlotte Despard, Evelyn Sharp, Mary Macarthur, Cicely Corbett Fisher, Lily Montagu and Margery Corbett-Ashby.

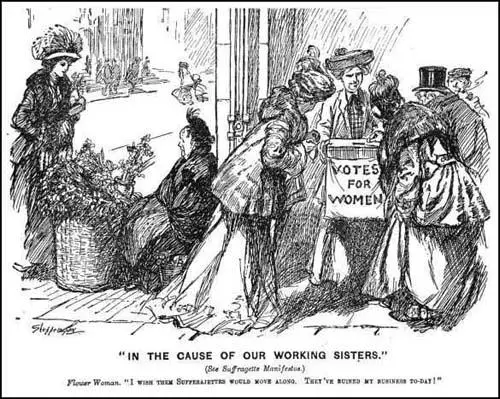

Most members of Women's Industrial Council were also active in the suffrage movement. Organizations such as the NUWSS and the Women's Freedom League worked closely with the council and other groups campaigning for better pay and conditions for women workers. By 1910 women made up almost one third of the workforce. Work was often on a part-time or temporary basis. It was argued that if women had the vote Parliament would be forced to pass legislation that would protect women workers.

The Women's Industrial Council concentrated on acquiring information about the problem and by 1914 the organisation had investigated one hundred and seventeen trades. In 1915 Clementina Black and her fellow investigators published their book Married Women's Work. This information was then used to persuade Parliament to take action against the exploitation of women in the workplace.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1901 Hilda Martindale became a factory inspector. She soon discovered that women and children were often working in terrible conditions. She described the problem in her book From One Generation to Another.

The hours of employment permissible under the Factory Acts in 1901 were long. Women and girls over 14 years could be employed 12 hours a day and on Saturday 8 hours. In addition, in certain industries, and dressmaking was one, an additional 2 hours could be worked by women on 30 nights in any 12 months.

Workrooms were often overcrowded, dirty, ill-ventilated, and insufficiently heated. The employment of little errand girls, usually only 14 years of age, soon attracted by attention. Their work was very varied - running errands, matching materials, taking out parcels, cleaning the workrooms, and often also helping in the work of the house. To be at the beck and call of all employed in a busy workshop was arduous and fatiguing. They could work legally from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. and often were sent out from the workshop a few minutes before 8 p.m. to take a dress to a customer living some distance away, which resulted in their not reaching home until a late hour. It was not surprising that the young persons in those workshops often looked weary and overdone; but there were plenty of girls to take their place, so they would not give in.

(2) On 22nd October 1907, Clementina Black spoke at the National Union Women Workers Conference about unskilled workers.

Trade unionism could not do for the unskilled trades and the sweated industries what it could do for other trades, and they must look to the law for protection. Surely the time was coming when the law, which was the representative of the organised will of the people, would declare that British workers should no longer work for less than they could live upon.

(3) In 1909 Clementina Black published her report Married Women's Work. Part of the report dealt with women who worked at home.

A very large majority of the women visited in their homes are kindly, industrious, reasonable, self-respecting persons and good citizens. The husbands in the main deserve the same praise… Parental affection seems to be the ruling passion of nearly all these fathers and mothers; they work hard with amazing patience in the hope of making their children happy… What is wrong is not the work for wages of married women, but the underpayment.

(4) In 1910, Charlotte Despard of the Women's Freedom League, made a speech about women workers and parliamentary reform.

Fundamentally all social and political questions are economic. With equal wages, the male worker would no longer fear that his female colleague might put him out of a job, and 'men and women will unite to effect a complete transformation to the industrial environment… A woman needs economic independence to live as an equal with her husband. It is indeed deplorable that the work of the wife and mother is not rewarded. I hope that the time will come when it is illegal for this strenuous form of industry to be unremunerated.

(5) Cicely Corbett Fisher, a representative of the Women's Industrial Council, gave a talk on sweated labour at East Grinstead in May 1912 .

Sweated labour may be defined as (1) working long hours, (2) for low wages, (3) under insanitary conditions. Although its victims include men as well as women, women form the great majority of sweated workers. The chief difficulty is combating this evil abuse is that nearly all sweated work is done in the homes of the workers. During the recent strike of Jam makers in Bermondsey the wages of the girls only just sufficed to provide them with food, and left no margin whatsoever for the purchase of clothes, for which they were entirely dependent on gifts from friends… Chief among these evils of sweated labour is the exploitation of child labour. Children of six years and upwards were employed after school hours, in helping to add to the family output and even infants of 3, 4 and 5 years of age work anything from 3 to 6 hours a day in such labour as carding hooks and eyes to add a few pence per week to the wages of the household.

(6) Evelyn Sharp, Unfinished Adventure (1933)

At first, all I saw in the enfranchisement of women was a possible solution of much that subconsciously worried me from the time when, as a London child, I had seen ragged and barefoot children begging in the streets, while I with brothers and nurses went by on the way to play in Kensington Gardens. Later, there were agricuktural labourers with their families, ill-fed, ill-housed, ill-educated, in the villages round my country home, and after that, the sweated workers.

I made spasmodic excursions into philanthropy, worked in girls' clubs and at children's play hours, joined the Anti-Sweating League, helped the Women's Industrial Council in one of its investigations. When the early sensational tactics of the militants focussed my attention upon the political futility of the voteless reformer, I joined the nearest suffrage society, which happened ironically to be the non-militant London Society.

(7) Editorial, Time and Tide (27th February, 1925)

The growing unrest which culminated in the Dock Strike of 1889 stimulated the organised women to revolt in the sweated trades of matchmaking and laundry work. Meetings held by the Amalgamated Society of Laundresses to protest against their exclusion from the Factory and Workshops Bill of 1891, enlisted public sympathy on their side. Women's unions - some eighty or ninety - sprang up under the auspices of the League, most of which expired through lack of money and of co-ordinated direction. It was not until 1903 that the woman capable of supplying both those essentials to successful agitation appeared upon the horizon. Her name was Mary Macarthur.

In amalgamating all these isolated efforts in the National Federation of Women Workers, Miss Macarthur rendered an inestimable service to the cause of the woman worker. Without her opportune support the strike among women employed at Millwall Food Preserving Factory, and those of the Cradley Heath Chainmakers and the Kilburnie netmakers would have been doomed to failure. Relief from their starvation wages and intolerable conditions was largely due to Miss Macarthur's able championship of their claims. As a result the membership of the Federation rapidly increased, and the movement spread from the ranks of industrial workers to the equally underpaid but better educated women employed in the distributive trades. To the establishment of Trade Boards, in 1909, for the purpose of regulating women's as well as men's wages, Miss Macarthur lent all her energy and influence. This innovation had the double effect of imposing minimum wage-rates in sweated industries and of demonstrating to the workers engaged therein the value of Union backing.