Tudor Heretics

The Roman Catholic Church dominated Europe in the Middle Ages. Like most organised religions, it was intolerant of those who disagreed with its beliefs. By the 11th century it had firmly established the law that heretics (people who maintain beliefs contrary to the established teachings of the Church) should be burned alive.

The Cathars in the south of France were considered to be heretics. They protested against what they perceived to be the moral, spiritual and political corruption of the Catholic Church. Fighting in wars, capital punishment and the killing of animals was abhorrent to the Cathars and their belief that men and women were equal also upset Pope Innocent III. In 1208 he gave orders for the Cathars to be either converted or exterminated.

The crusader army came under the command of the papal legate Arnaud-Amaury, Abbot of Cîteaux. In the first significant engagement of the war, the town of Béziers was besieged on 22nd July 1209. The Catholic inhabitants of the city were granted the freedom to leave unharmed, but many refused and opted to stay with the Cathars. When the Abbot gave orders for all the inhabitants to be killed, one of the soldiers asked how they would distinguish the Cathars from the Catholics. He replied: "Kill them all. For the Lord knoweth them that are His." It is estimated that over 15,000 people were executed that day. (1)

John Wycliffe and the Lollards

In the 14th century a new heresy appeared, inspired by the English priest and theologian John Wycliffe. On 26th July 1374, Wycliffe was appointed as one of five new envoys to continue negotiations in Bruges with papal officials over clerical taxes and provisions. The negotiations ended without conclusion, and the representatives of each side retired for further consultation. (2) It has been argued that the failure of these negotiations had a profound impact on his religious beliefs. "He began to attack Rome's control of the English Church and his stance became increasingly anti-Papal resulting in condemnation of his teachings and threats of excommunication." (3)

Wycliffe antagonized the orthodox Church by disputing transubstantiation, the doctrine that the bread and wine used in religious services become the actual body and blood of Christ. Wycliffe developed a strong following and those who shared his beliefs became known as Lollards. They got their name from the word "lollen", which signifies to sing with a low voice. The term was applied to heretics because they were said to communicate their views in a low muttering sound. (4)

As one of the historians of this period of history, John Foxe, has pointed out: "Wycliffe, seeing Christ's gospel defiled by the errors and inventions of these bishops and monks, decided to do whatever he could to remedy the situation and teach people the truth. He took great pains to publicly declare that his only intention was to relieve the church of its idolatry, especially that concerning the sacrament of communion. This, of course, aroused the anger of the country's monks and friars, whose orders had grown wealthy through the sale of their ceremonies and from being paid for doing their duties. Soon their priests and bishops took up the outcry." (5)

In 1382 John Wycliffe was condemned as a heretic and was forced into retirement. (6) Archbishop William Courtenay urged Parliament to pass a Statute of the Realm against preachers such as Wycliffe: "It is openly known that there are many evil persons within the realm, going from county to county, and from town to town, in certain habits, under dissimulation of great holiness, and without the licence ... or other sufficient authority, preaching daily not only in churches and churchyards, but also in markets, fairs, and other open places, where a great congregation of people is, many sermons, containing heresies and notorious errors." (7)

The Lollards presented a petition to Parliament in 1394, claiming: "That the English priesthood derived from Rome, and pretending to a power superior to angels, is not that priesthood which Christ settled upon his apostles. That the enjoining of celibacy upon the clergy was the occasion of scandalous irregularities. That the pretended miracle of transubstantiation runs the greatest part of Christendom upon idolatry. That exorcism and benedictions pronounced over wine, bread, water, oil, wax, and incense, over the stones for the altar and the church walls, over the holy vestments, the mitre, the cross, and the pilgrim's staff, have more of necromancy than religion in them.... That pilgrimages, prayers, and offerings made to images and crosses have nothing of charity in them and are near akin to idolatry." (8)

During the 14th century several Lollards were charged and convicted with heresy. John Badby, a tailor from Evesham was charged with heresy and appeared before Thomas Peverell, the Bishop of Worcester on 2nd January 1409. According to his biographer, Peter McNiven, Badby had... achieved notoriety by his uninhibited denial of the doctrine of transubstantiation... Badby insisted that the bread in the eucharist was not, and could not be, miraculously transformed into Christ's body." Although Badby was adjudged a heretic, and so liable to the death penalty, the church had no wish to make martyrs of insignificant men and was released. (9)

Prince Henry (the future Henry V) suggested to the House of Commons that they might endorse a Lollard solution to the crown's financial problems by the "wholesale confiscation of the church's temporal possessions". Archbishop Thomas Arundel was horrified by this suggestion and persuaded Henry IV to make an example of a Lollard leader.

John Badby appeared before a convocation of the clergy on 1st March 1410. The author of Heresy and Politics in the Reign of Henry IV: The Burning of John Badby (1987) has argued that this "hearing became a show trial of national importance". The principal charge against him was that he believed the "bread was not turned into the actual physical body of Christ upon consecration".

Badby refused to renounce his beliefs and on 15th March, 1409, he was declared a heretic, and was turned over to the secular authorities for punishment. "That afternoon, John Badby was brought to Smithfield and put in an empty barrel, bound with chains to the stake, and surrounded by dry wood. As he stood there, the king's eldest son happened by and encouraged Badby to save himself while there was still time, but Badby refused to change his opinions. The barrel was put over him and the fire lit." (10)

John F. Harrison, the author of The Common People (1984) has pointed out that "John Badby was one of the earliest of a succession of Lollard martyrs memorialized for later generations of humble readers in the gruesome illustrations to Foxe's Book of Martyrs. It is clear from John Foxe's great work that Lollards survived into the 1530s, and that most of them belonged to the common people... Tradesmen and craftsmen seem to have been more numerous than husbandmen, and there was a handful of merchants and professional men from the towns, especially London." (11)

Act for the Burning of Heretics

Acts of Parliament were passed in 1382, 1401 and 1414, that gave statutory authority for burning heretics. The 1401 Act stated that when a person had been condemned as a heretic by the ecclesiastical courts, the King had to issue a warrant ordering the civil power - the sheriffs and justices of the peace - to burn the heretic alive. When a person was accused of heresy, they were brought before the court of the Bishop of the diocese. The accused heretic was given every encouragement to recant. If they refused they were burnt at the stake. Between 1401 and 1440 sixteen heretics were burned in England. (12)

The persecution of Lollards continued throughout the fifteenth century. In the reign of Henry VII, twelve heretics were burned. The first to suffer was Joan Broughton, who according to John Foxe was an eighty-year-old widow who was accused of holding the opinions of John Wycliffe: "She held eight of his ten opinions so firmly that all the doctors of London could not make her give up even one of them. Told she would burn for her obstinacy, Mrs. Boughton defied the threat, saying she so loved by God that she didn't fear the fire." Broughton was burnt at Smithfield on 28th April 1494. (13)

Faced with the possibility of being burnt at the stake, most people recanted. This was a formal retraction or disavowal of the belief to which one has previously committed oneself. Those who recanted were forced to take part in the ceremony known as "carrying his faggot". A faggot was bundle of sticks bound together. The heretic was taken to the place of execution carrying a faggot on his shoulder, and when the fire was lit they threw the faggot into the fire. Sometimes the heretic was also required to preach a sermon repudiating their heresy and begging for the forgiveness of the Church. (14)

In 1506 a group of heretics in Lincoln were arrested. The leader of the group was William Tylsworth and it was decided to burn him at the stake. His married daughter, Joan Clerke, was forced to set fire to her own father. "At the same time, her husband, John Clerke, did penance by carrying a fagot of wood, as did between twenty-three and sixty others. Those doing penance at Tylsworth's burning were then compelled to wear badges and travel to other towns to do further penance over the space of seven years. Several of them were branded on the cheek for their offences." (15)

Heresy in Tudor England

The main cause of heresy in Tudor England concerned the dispute over the doctrine of transubstantiation. According to the teaching of the Catholic Church, the bread and the wine used in the sacrament of the Eucharist become in actual reality the body and blood of Christ. In May 1511 six men and four women, from Tenterden in Kent, were denounced as heretics for claiming that "the sacrament of the altar was not the body of Christ but merely material bread". They were all tried as heretics and they all recanted. However, two of the men had recanted before and so were burnt at the state. (16)

John Foxe pointed out that in the 16th century, Lollards and other heretics were opposed to certain aspects of the Catholic Church: "The religion of Christ, meant to be spirit and truth, had been turned into nothing but outward observances, ceremonies, and idolatry. We had so many saints, so many gods, so many monasteries, so many pilgrimages. We had too many churches, too many relics (true and fake), too many untruthful miracles. Instead of worshipping the only living Lord, we worshipped dead bones; in place of immortal Christ, we worshipped mortal bread.

No care was taken about how the people were led as long as the priests were fed. Instead of God's Word, man's word was obeyed; instead of Christ's testament, the pope's canon. The law of God was seldom read and never understood, so Christ's saving work and the effect on man's faith were not examined. Because of this ignorance, errors and sects crept into the church, for there was no foundation for the truth that Christ willingly died to free us from our sins - not bargaining with us but giving to us." (17)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 - $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Lollards who survived into the 16th century, embraced the ideas of Martin Luther. This included William Tyndale who worked for many years in completing the English translation of the English Bible that had been started by John Wycliffe and the Lollards. (18) This was a very dangerous activity for ever since 1408 to translate anything from the Bible into English was a capital offence. (19) Tyndale argued: "All the prophets wrote in the mother tongue... Why then might they (the scriptures) not be written in the mother tongue... They say, the scripture is so hard, that thou could never understand it... They will say it cannot be translated into our tongue... they are false liars." In Cologne he translated the New Testament into English and it was printed by Protestant supporters in Worms in 1526. (20)

Thomas More and Heretics

Thomas Bilney became a well-known preacher against idolatry. Twice he was pulled from his pulpit by some members of his congregation. (21) At Ipswich, Bilney denounced pilgrimages to popular shrines like Our Lady of Walsingham and warned of the worthlessness of prayers to the saints, while at Willesden he attacked the custom of leaving offerings before images. Bilney called on Henry VIII to destroy these images. (22)

In 1527 Bilney's attacks "on the insolence, pomp, and pride of the clergy" drew the attention of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. On 29th November, Bilney was brought before Wolsey and a group of bishops, priests, and lawyers at Westminster. Also in attendance was Sir Thomas More. It has been argued by Jasper Ridley: "This was unprecedented, for a common lawyer and layman would not ordinarily have joined the bishops and canon lawyers in the examination of a heretic." (23)

Thomas Bilney declared that he had not "taught the opinions" of Martin Luther. Bilney was now handed over to Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall who declared he "was a wicked and detestable heretic". Bilney was held in custody and on 7th December he agreed to recant his beliefs. According to John Foxe: "He was sentenced to prison for some time and forced to do penance by going before the procession at St. Paul's bareheaded and carrying a faggot on his shoulder, then standing before the preacher during the sermon." (24)

Thomas Bilney remained in prison until his release early in January 1529. On his return to Cambridge he went to see Hugh Latimer and asked him to hear his confession. (25) According to John Foxe: "Latimer was so moved by what he heard that he left his study of the Catholic doctors to learn true divinity. Where before he was an enemy of Christ, he now became a zealous seeker of Him... Latimer and Bilney stayed at Cambridge for some time, having many conversations together; the place they walked soon became known as Heretics' Hill. Both of them set a good Christian example by visiting prisoners, helping the needy, and feeding the hungry." (26)

Jasper Ridley, the author of The Statesman and the Fanatic (1982) points out that no heretics were burned between 1521 and 1529 when Cardinal Thomas Wolsey was Lord Chancellor. However, things changed when Sir Thomas More replaced Wolsey: "Apart from other factors, these heretics were burned when More was Chancellor because they refused to recant, or, having recanted, relapsed into heresy, whereas in Wolsey's time all the heretics whom he examined recanted at their trial. But there is no doubt that at least part of the reason is that More was a far more zealous persecutor than Wolsey." (27) Over the next four years thirteen people were burnt at the stake for heresy.

According to Peter Ackroyd, the appointment of Thomas More was a shrewd political move. "Since More was known to be an avid hunter of heretics, it was evident proof that Henry did not wish to disavow the orthodox Church. In fact, More started his pursuit within a month of taking his position he arrested a citizen of London, Thomas Phillips, on suspicion of heresy... It was the beginning of the new chancellor's campaign of terror against the heretics." (28)

More was opposed to Henry VIII divorcing Catherine of Aragon, but came under increasing pressure from other members of the Privy Council to agree with this policy. (29) When this was unsuccessful, he was excluded from the inner circle of councillors concerned with the divorce proceedings. More now concentrated his energies on persecuting Heretics.

In 1530 More issued two proclamations proscribing a number of publications and banned the importation of any foreign imprints of English works. More imprisoned a number of men for owning banned books. More also ordered the execution of three heretics and publicly approved of the execution of others. "The vigour with which More pursued heretics through the courts was mirrored by the relentlessness with which he fought them... The times demanded strictness, he repeatedly argued, because the stakes were so high. No other aspect of More's life has engendered greater controversy than his persecution of heretics. Critics argue that as one of Europe's leading intellectuals, and one with particularly strong humanist leanings, More should have rejected capital punishment of heretics. His supporters point out that he was a product of his times, and that those men he most admired... lamented but accepted as necessary the practice of executing heretics." (30)

In early 1531 Thomas Bilney announced to his friends that he was "going up to Jerusalem" and set off for Norwich to court martyrdom. He began to preach in the open air, renounced his earlier recantation, and distributed copies of the English Bible that had been translated by William Tyndale. He was arrested in March and as a relapsed heretic he knew he would be burnt at the stake. (31)

John Foxe later described his execution in August 1531: "Bilney approached the stake in a layman's gown, his arms hanging out, his hair mangled by the church's ritual divestiture of office. He was given permission to speak to the crowd and told them not to blame the friars present for his death and then said his private prayers. The officers put reeds and wood around him and lit the fire, which flared up rapidly, deforming Bilney's face as he held up his hands." Foxe claimed he called out "Jesus" and "I believe". (32)

Richard Bayfield was arrested at a London bookbinder's in October 1531. He was imprisoned, and interrogated by Sir Thomas More. Bayfield was a close associate of William Tyndale and arranged for his English translation of the Bible to be imported to England. It is estimated that during this period 18,000 copies of this book were printed and smuggled into England.

Jasper Ridley has argued that the Tyndale Bible created a revolution in religious belief: "The people who read Tyndale's Bible could discover that although Christ had appointed St Peter to be head of his Church, there was nothing in the Bible which said that the Bishops of Rome were St Peter's successors and that Peter's authority over the Church had passed to the Popes... The Bible stated that God had ordered the people not to worship graven images, the images and pictures of the saints, and the station of the cross, should not be placed in churches and along the highways... Since the days of Pope Gregory VII in the eleventh century the Catholic Church had enforced the rule that priests should not marry but should remain apart from the people as a special celibate caste... The Protestants, finding a text in the Bible that a bishop should be the husband of one wife, believed that all priests should be allowed to marry." (33)

As Andrew Hope points out Bayfield was an important figure in the illegal importation of English books: "Bayfield... took on the role of the main supplier of prohibited reformation books to the English market, a role vacant since the arrest of Thomas Garrett in 1528.... He is known to have sent three major consignments to England, the first via Colchester in mid-1530, the second via St Katharine by the Tower, London, in late 1530, and the third via Norfolk about Easter 1531. The second consignment was wholly intercepted by Lord Chancellor Sir Thomas More, and the third probably partially so." (34)

Richard Bayfield was imprisoned, and interrogated and tortured by Thomas More. "Richard Bayfield was cast into prison, and endured some whipping, for his adherence to the doctrines of Luther... The sufferings this man underwent for the truth were so great that it would require a volume to contain them. Sometimes he was shut up in a dungeon, where he was almost suffocated by the offensive and horrid smell of filth and stagnant water. At other times he was tied up by the arms, until almost all his joints were dislocated. He was whipped at the post several times, until scarcely any flesh was left on his back; and all this was done to make him recant. He was then taken to the Lollard's Tower in Lambeth palace, where he was chained by the neck to the wall, and once every day beaten in the most cruel manner by the archbishop's servants." (35)

According to Jasper Ridley More later attempted to discredit Bayfield by claiming he had two wives. His friends claimed this was untrue. More suggested that Bayfield had relapsed into heresy, "like a dog returning to his vomit" but was "willing to recant again as long as he thought that there was any chance of saving his life". (36)

Richard Bayfield was convicted as a relapsed heretic, degraded, and "burnt with excruciating slowness" at Smithfield, on 27th November, 1531. (37) According to one source More stamped on Bayfield's ashes and cursed him." (38) The following month, on 3rd December, Thomas More issued a proclamation denouncing William Tyndale as a "spreader of seditious heresy". (39)

Thomas More also sent a close friend, Sir Thomas Elyot, to try to arrange the arrest of William Tyndale who was living in Brussels. This ended in failure and the next person to try was Henry Phillips. He had gambled away money entrusted to him by his father to give to someone in London, and had fled abroad. Phillips offered his services to help capture Tyndale. After befriending Tyndale he led him into a trap on 21st May, 1535. (40) Tyndale was taken at once to Pierre Dufief, the Procurer-General, who immediately raided Poyntz's house and took away all Tyndale's property, including his books and papers. Luckily, his work on the Old Testament was being kept by John Rogers. Tyndale was taken to Vilvorde Castle, outside Brussels, where he was kept for the next sixteen months. (41)

Pierre Dufief had a reputation for hunting down heretics. He was motivated by the fact he was given a proportion of the confiscated property of his victims, and a large fee. Tyndale was tried by seventeen commissioners, led by three chief accusers. At their head was the greatest heresy-hunter in Europe, Jacobus Latomus, from the new Catholic University of Louvain, a long-time opponent of Desiderius Erasmus as well as of Martin Luther. Tyndale conducted his own defence. He was found guilty but he was not burnt alive, as a mark of his distinction as a scholar. On 6th October, 1536, he was strangled first, and then his body was burnt. John Foxe reports that his last words were "Lord, open the king of England's eyes!" (42)

Lord Chancellor Thomas More was a strong supporter of the Catholic Church and he was determined to destroy the Protestant movement in England. As a writer, More was aware of the power of books to change people's opinions. He therefore drew up a list of Protestant books that were to be banned. This included the English translation of the Bible by William Tyndale. More attempted to make life difficult for those publishing such books. He introduced a new law that required the name and address of the printer to be printed in every book published in England. People caught owning Protestant books were sat facing back-to-front on a horse. Wearing placards explaining their crimes, these people were walked through the streets of London. More also organized public burnings of Protestant books. People found guilty of writing and selling Protestant books were treated more harshly. Like those caught making Protestant sermons, they were sometimes burnt at the stake.

More wrote to a friend that he especially hated the Anabaptists: "The past centuries have not seen anything more monstrous than the Anabaptists". His biographer, Jasper Ridley, has argued: "As Thomas More approached the age of fifty, all the conflicting trends in his strange character blended into one, and produced the savage persecutor of heretics who devoted his life to the destruction of Lutheranism. To say that he suffered from paranoia on this subject would be to resort to a glib phrase, not a serious psychiatric analysis; but it is unquestionable that More, like other persecutors throughout history, believed that the foundations of civilisation, and all that he valued as sacred, were threatened by the forces of evil, and that it was his mission to exterminate the enemy by all means, including torture and lies. The worst of all the heretics were the Anabaptists, the most extreme of all the Protestant sects, who were already causing great concern to the authorities in Germany and the Netherlands. They not only rejected infant baptism, but believed, like the inhabitants of Utopia, that goods should be held in common." (43)

Thomas More wrote that of all the heretical books published in England, Tyndale's translation of the New Testament, was the most dangerous. He began his book, Confutation of Tyndale's Answer, with a striking opening sentence: "Our Lord send us now some years as plenteous of good corn we have had some years of late plenteous of evil books. For they have grown so fast and sprung up so thick, full of pestilent errors and pernicious heresies, that they have infected and killed I fear me more simple souls than the famine of the dear years have destroyed bodies." (44)

One of Tyndale's associates, John Frith arrived in England in July 1531 to help distribute Tyndale's Bible. Frith was arrested when he was suspected that he might have stolen goods hidden in his bag. When the bag was opened they discovered that it contained English Bibles. After the authorities discovered his real name he was sent to the Tower of London. While in the Tower he wrote an extended essay where he explained his arguments against Catholic ideas such as transubstantiation. It was smuggled out and read by his supporters. (45) "He argued first that the matter of the sacrament was no necessary article of faith under pain of damnation. Next, that Christ had a natural body (apart from sin), and could not be in two places at once. Third, that 'This is my body' was not literal. Last, that what the church practised was not what Christ instituted." (46)

Thomas More obtained a copy of the essay. Catholics like More upheld the doctrine of transubstantiation, whereby the bread and wine became in actual fact the body and blood of Christ. It is believed because it is impossible, it is proof of the overwhelming power of God. Frith, a follower of Martin Luther, who believed in the real presence of Christ in the sacrament, but denied that he was there "in substance". Luther believed in what became known as consubstantiation or sacramental union, whereby the integrity of the bread and wine remain even while being transformed by the body and blood of Christ. (47)

According to John Foxe, Frith and More were engaged in a long debate on two main issues: "While there (in the Tower of London), he and More wrote back and forth to each other, arguing about the sacrament of communion and purgatory. Frith's letters were always moderate, calm, and learned. Where he was not forced to argue, he tended to give in for the sake of peace." (48)

Thomas More and Bishop Stephen Gardiner suggested to Henry VIII that an example should be made of John Frith. Henry ordered Frith to recant or be condemned. Frith refused and he was examined at St Paul's Cathedral on 20th June 1533. (49) His examinations revolved around two points: purgatory and the substance of the sacrament. Frith wrote to his friends, "I cannot agree with the divines and other head prelates that it is an article of faith that we must believe - under pain of damnation - that the bread and wine are changed into the body and blood of our Savior Jesus Christ while their form and shape stay the same. Even if this were true, it should not be an article of faith."

John Frith was burnt at the stake on 4th July 1533. It was reported that "Frith was led to the stake, where he willingly embraced the wood and fire, giving a perfect testimony with his own life. The wind blew the fire away from him, toward Andrew Hewet, who was burning with him, so Frith's death took longer than usual, but he seemed to be happy for his companion and not to care about his own prolonged suffering." (50)

Act of Supremacy

In March 1534 Pope Clement VII eventually made his decision. He announced that Henry's marriage to Anne Boleyn was invalid. Henry reacted by declaring that the Pope no longer had authority in England. In November 1534, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy. This gave Henry the title of the "Supreme head of the Church of England". A Treason Act was also passed that made it an offence to attempt by any means, including writing and speaking, to accuse the King and his heirs of heresy or tyranny. All subjects were ordered to take an oath accepting this. (51)

Sir Thomas More and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, refused to take the oath and were imprisoned in the Tower of London. More was summoned before Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell at Lambeth Palace. More was happy to swear that the children of Anne Boleyn could succeed to the throne, but he could not declare on oath that all the previous Acts of Parliament had been valid. He could not deny the authority of the pope "without the jeoparding of my soul to perpetual damnation." (52)

Elizabeth Barton was arrested and executed for prophesying the King's death within a month if he married Anne Boleyn. (53) Henry's daughter, Mary I, also refused to take the oath as it would mean renouncing her mother, Catherine of Aragon. On hearing this news, Anne Boleyn apparently said that the "cursed bastard" should be given "a good banging". Mary was only confined to her room and it was her servants who were sent to prison.

On 15th June, 1534, it was reported to Thomas Cromwell that the Observant Friars of Richmond refused to take the oath. Two days later two carts full of friars were hanged, drawn and quartered for denying the royal supremacy. A few days later a group of Carthusian monks were executed for the same offence. "They were chained upright to stakes and left to die, without food or water, wallowing in their own filth - a slow, ghastly death that left Londoners appalled". (54) Cromwell told More that the example he was setting was resulting in other men being executed. More responded: "I do nobody harm. I say none harm, I think none harm, but wish everybody good. And if this be not enough to keep a man alive, in good faith I long not to live." (55)

In May 1535, Pope Paul III created Bishop John Fisher a Cardinal. This infuriated Henry VIII and he ordered him to be executed on 22nd June at the age of seventy-six. A shocked public blamed Queen Anne for his death, and it was partly for this reason that news of the stillbirth of her child was suppressed as people might have seen this as a sign of God's will. Anne herself suffered pangs of conscience on the day of Fisher's execution and attended a mass for the "repose of his soul". (56)

Henry VIII decided it was time that Thomas More was tried for treason. The trial was held in Westminster Hall. More denied that he had ever said that the King was not Head of the Church, but claimed that he had always refused to answer the question, and that silence could never constitute an act of high treason. The prosecution cited the statement that he had made to Thomas Cromwell on 3rd June, where he argued that the Act of Supremacy was like a two-edged sword in requiring a man either to swear against his conscience or to suffer death for high treason. (57)

The verdict was never in doubt and Thomas More was convicted of treason. Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley "passed sentence of death - the full sentence required by law, that More was to be hanged, cut down while still living, castrated, his entrails cut out and burned before his eyes, and then beheaded. Henry VIII commuted the sentence to death by the headsman's axe. (58)

Thomas Cromwell & Religious Reform

With the death of Sir Thomas More, government figures sympathetic to Protestantism became more powerful. Thomas Cromwell, now invited leading reformers such as Robert Barnes, who were living in exile, to return to England. As Carl R. Trueman has pointed out: "From now on Barnes's career would be inextricably intertwined with the fortunes of Cromwellian domestic and foreign policy." (59)

In September 1535, another important reformer, Hugh Latimer was appointed as Bishop of Worcester. Once established in his diocese he embarked upon a programme of dismantling images and promoting new standards of preaching. He stripped the statue of the Virgin that stood in Worcester Cathedral. He also removed the renowned relic of Christ's blood from Hailes Abbey. (60) In June 1536 Latimer was chosen to preach before the senior clergy assembled at St Paul's Cathedral where he attacked the activities of Pope Paul III. (61) Other reformers were also appointed to senior posts. This included Nicholas Shaxton and Nicholas Ridley.

During this period no Protestants were executed for being heretics. However, a Roman Catholic, Friar John Forest, who had been a religious adviser to Catherine of Aragon, was charged with heresy. In the whole history of the religious persecutions in Tudor England, Forest was the only Roman Catholic who was accused of this crime. He was sentenced to be both hanged for treason and burnt for heresy. Bishop Latimer agreed to preach the sermon at Forest's execution on 22nd May 1538. His sermon lasted for three hours while he waited for death. Latimer told Cromwell that he made it a long sermon to increase Forest's suffering. "Forest was chained to a gallows which was placed above the fire which burned below him... When the flames reached his feet, he drew them up, then bravely lowered them into the fire, and remained there till he burned to death." (62)

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, was also sympathetic to the ideas of people such as Martin Luther. He joined forces with Cromwell, Latimer, Ridley and Shaxton to introduce religious reforms. They wanted the Bible to be available in English. This was a controversial issue as William Tyndale had been denounced as a heretic and ordered to be burnt at the stake by Henry VIII eleven years before, for producing such a Bible. The edition they wanted to use was that of Miles Coverdale, that was a reworking of the one produced by Tyndale. Cranmer approved the Coverdale version on 4th August 1538, and asked Cromwell to present it to the king in the hope of securing royal authority for it to be available in England. (63)

Henry agreed to the proposal on 30th September. Every parish had to purchase and display a copy of the Coverdale Bible in the nave of their church for everybody who was literate to read it. "The clergy was expressly forbidden to inhibit access to these scriptures, and were enjoined to encourage all those who could do so to study them." (56) Cranmer was delighted and wrote to Cromwell praising his efforts and claiming that "besides God's reward, you shall obtain perpetual memory for the same within the realm." (64)

Six Articles

In May 1539 the bill of the Six Articles was presented by Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk in Parliament. It was soon clear that it had the support of Henry VIII. Although the word "transubstantiation" was not used, the real presence of Christ's very body and blood in the bread and wine was endorsed. So also was the idea of purgatory. The six articles presented a serious problem for Latimer and other religious reformers. Latimer had argued against transubstantiation and purgatory for many years. Latimer now faced a choice between obeying the king as supreme head of the church and standing by the doctrine he had had a key role in developing and promoting for the past decade. (65)

Bishop Hugh Latimer and Bishop Nicholas Shaxton both spoke against the Six Articles in the House of Lords. Thomas Cromwell was unable to come to their aid and in July they were both forced to resign their bishoprics. For a time it was thought that Henry would order their execution as heretics. He eventually decided against this measure and instead they were ordered to retire from preaching.

On 10th June, 1540, Thomas Cromwell arrived slightly late for a meeting of the Privy Council. Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, shouted out, "Cromwell! Do not sit there! That is no place for you! Traitors do not sit among gentlemen." The captain of the guard came forward and arrested him. (66) Cromwell was charged with treason and heresy. Norfolk went over and ripped the chains of authority from his neck, "relishing the opportunity to restore this low-born man to his former status". Cromwell was led out through a side door which opened down onto the river and taken by boat the short journey from Westminster to the Tower of London. (67)

Thomas Cromwell was convicted by Parliament of treason and heresy on 29th June and sentenced him to be hung, drawn and quartered. He wrote to Henry VIII soon afterwards and admitted "I have meddled in so many matters under your Highness that I am not able to answer them all". He finished the letter with the plea, "Most gracious prince I cry for mercy, mercy, mercy." Henry commuted the sentence to decapitation, even though the condemned man was of lowly birth. (68)

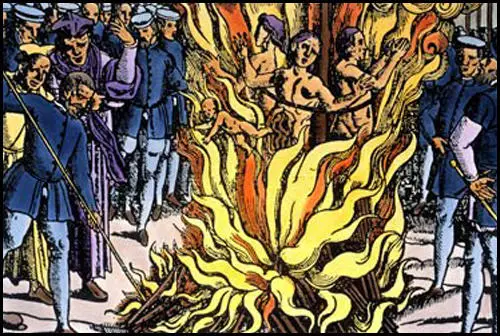

On 22nd July, 1540, Robert Barnes, Thomas Garrard and William Jerome, were attainted as heretics, a procedure which denied them the chance to defend themselves in court, and sentenced to death; their heresies were not specified. At the stake, on 30th July, Garrard and his fellows maintained that they did not know why they were being burnt, and that they died guiltless. Richard Hilles, who observed the executions, commented that the men "remained in the fire without crying out, but were as quiet and patient as though they felt no pain". The men were burnt at the same time that three Catholics, Thomas Abell, Edward Powell, and Richard Fetherstone, were hanged, drawn, and quartered for treason. (69)

David Loades, the author of Thomas Cromwell (2013), has argued: "None of these men was guilty of the radical heresies with which they were charged, but it was deemed necessary as part of the campaign against Cromwell to represent him as the controlling force behind a dangerous heretical conspiracy - and these were the other conspirators, or some of them. Like him they were condemned by Act of Attainder, and Barnes at least proclaimed his innocence in his last speech to the crowd. He had never preached sedition or disobedience, and had used his learning against the Anabaptists. He did not know why he was condemned to die, but the true answer lay not in his own doings or beliefs, but in his association with Thomas Cromwell." (70)

On 28th July, Thomas Cromwell walked out onto Tower Green for his execution. In his speech from the scaffold he denied that he had aided heretics, but acknowledged the judgment of the law. He then prayed for a short while before placing his head on the block. The executioner bungled his work, and took two strokes to sever the neck of Cromwell. He suffered a particularly gruesome execution before what was left of his head was set upon a pike on London Bridge. (71)

Anne Askew

Bishop Stephen Gardiner now attempted to remove Lutherism from England. One of his first targets was Anne Askew. When she was fifteen her family forced her to marry Thomas Kyme. Anne rebelled against her husband by refusing to adopt his surname. The couple also argued about religion. Anne was a supporter of Martin Luther, while her husband was a Roman Catholic. (72)

From her reading of the Bible she believed that she had the right to divorce her husband. For example, she quoted St Paul: "If a faithful woman have an unbelieving husband, which will not tarry with her she may leave him"? Askew was well connected. One of her brothers, Edward Askew, was cup-bearer to the king, and her half-brother Christopher, was gentleman of the privy chamber. She was also friendly with John Lascelles, another important figure in the reform movement.

Alison Plowden has argued that "Anne Askew is an interesting example often educated, highly intelligent, passionate woman destined to become the victim of the society in which she lived - a woman who could not accept her circumstances but fought an angry, hopeless battle against them." (73) In 1544 Askew decided to travel to London and request a divorce from Henry VIII. This was denied and documents show that a spy was assigned to keep a close watch on her behaviour. She made contact with Joan Bocher, a leading figure in the Anabaptists. One spy who had lodgings opposite her own reported that "at midnight she beginneth to pray, and ceaseth not in many hours after." (74)

In March 1546 she was arrested on suspicion of heresy. (75) She was questioned about a book she was carrying that had been written by John Frith, a Protestant priest who had been burnt for heresy in 1533, for claiming that neither purgatory nor transubstantiation could be proven by Holy Scriptures. She was interviewed by Edmund Bonner, the Bishop of London who had obtained the nickname of "Bloody Bonner" because of his ruthless persecution of heretics. (76)

After a great deal of debate Anne Askew was persuaded to sign a confession which amounted to an only slightly qualified statement of orthodox belief. With the help of her friend, Edward Hall, the Under-Sheriff of London, she was released after twelve days in prison. Askew's biographer, Diane Watt, argues: "It would appear that at this stage Bonner was concerned more about the heterodoxy of Askew's beliefs than with her connections and contacts, and that he principally wanted to rid himself of a woman whom he found obstinate and vexatious. Her treatment during her first examination suggests, therefore, that Askew's opponents did not yet view her as particularly influential or important." (77) Askew was released and sent back to her husband. However, when she arrived back to Lincolnshire she went to live with her brother, Sir Francis Askew.

In February 1546 conservatives in the Church of England, led by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, began plotting to destroy the radical Protestants. (78) He gained the support of Henry VIII. As Alison Weir has pointed out: "Henry himself had never approved of Lutheranism. In spite of all he had done to reform the church of England, he was still Catholic in his ways and determined for the present to keep England that way. Protestant heresies would not be tolerated, and he would make that very clear to his subjects." (79) In May 1546 Henry gave permission for twenty-three people suspected of heresy to be arrested. This included Anne Askew.

Gardiner selected Askew because he believed she was associated with Henry's sixth wife, Catherine Parr. (80) Catherine also criticised legislation that had been passed in May 1543 that had declared that the "lower sort" did not benefit from studying the Bible in English. The Act for the Advancement of the True Religion stated that "no women nor artificers, journeymen, serving men of the degree of yeomen or under husbandmen nor labourers" could in future read the Bible "privately or openly". Later, a clause was added that did allow any noble or gentlewoman to read the Bible, this activity must take place "to themselves alone and not to others". Catherine ignored this "by holding study among her ladies for the scriptures and listening to sermons of an evangelical nature". (81)

Gardiner believed the Queen was deliberately undermining the stability of the state. Gardiner tried his charm on Askew, begging her to believe he was her friend, concerned only with her soul's health, she retorted that that was just the attitude adopted by Judas "when he unfriendly betrayed Christ". On 28th June she flatly rejected the existence of any priestly miracle in the eucharist. "As for that ye call your God, it is a piece of bread. For a more proof thereof... let it but lie in the box three months and it will be mouldy." (82)

Gardiner instructed Sir Anthony Kingston, the Constable of the Tower of London, to torture Askew in an attempt to force her to name Catherine Parr and other leading Protestants as heretics. Kingston complained about having to torture a woman (it was in fact illegal to torture a woman at the time) and the Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley and his assistant, Richard Rich took over operating the rack. Despite suffering a long period on the rack, Askew refused to name those who shared her religious views. According to Askew: "Then they did put me on the rack, because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen, to be of my opinion... the Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands, till I was nearly dead. I fainted... and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours arguing with the Lord Chancellor, upon the bare floor... With many flattering words, he tried to persuade me to leave my opinion... I said that I would rather die than break my faith." (83) Afterwards, Anne's broken body was laid on the bare floor, and Wriothesley sat there for two hours longer, questioning her about her heresy and her suspected involvement with the royal household. (84)

Askew was removed to a private house to recover and once more offered the opportunity to recant. When she refused she was taken to Newgate Prison to await her execution. On 16th July 1546, Agnew "still horribly crippled by her tortures" was carried to execution in Smithfield in a chair as she could not walk and every movement caused her severe pain. (85) It was reported that she was taken to the stake which had a small seat attached to it, on which she sat astride. Chains were used to bind her body firmly to the stake at the ankles, knees, waist, chest and neck. (86)

Anne Askew's executioner helped her die quickly by hanging a bag of gunpowder around her neck. (87) Also executed at the same time was John Lascelles, John Hadlam and John Hemley. (88) John Bale wrote that “Credibly am I informed by various Dutch merchants who were present there, that in the time of their sufferings, the sky, and abhorring so wicked an act, suddenly altered colour, and the clouds from above gave a thunder clap, not unlike the one written in Psalm 76. The elements both declared wherein the high displeasure of God for so tyrannous a murder of innocents." (89)

Bishop Stephen Gardiner had a meeting with Henry VIII after the execution of Anne Askew and raised concerns about his wife's religious beliefs. Henry, who was in great pain with his ulcerated leg and at first he was not interested in Gardiner's complaints. However, eventually Gardiner got Henry's agreement to arrest Catherine Parr and her three leading ladies-in-waiting, "Herbert, Lane and Tyrwhit" who had been involved in reading and discussing the Bible. (90)

Henry then went to see Catherine to discuss the subject of religion. Probably, aware what was happening, she replied that "in this, and all other cases, to your Majesty's wisdom, as my only anchor, Supreme Head and Governor here in earth, next under God". He reminded her that in the past she had discussed these matters. "Catherine had an answer for that too. She had disputed with Henry in religion, she said, principally to divert his mind from the pain of his leg but also to profit from her husband's own excellent learning as displayed in his replies." (91) Henry replied: "Is it even so, sweetheart? And tended your arguments to no worse end? Then perfect friends we are now again, as ever at any time heretofore." (92) Gilbert Burnett has argued that Henry put up with Catherine's radical views on religion because of the good care she took of him as his nurse. (93)

The next day Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley arrived with a detachment of soldiers to arrest Catherine. Henry told him he had changed his mind and sent the men away. Glyn Redworth, the author of In Defence of the Church Catholic: The Life of Stephen Gardiner (1990) has disputed this story because it relies too much on the evidence of John Foxe, a leading Protestant at the time. (94) However, David Starkey, the author of Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (2003) has argued that some historians "have been impressed by the wealth of accurate circumstantial detail, including, in particular, the names of Catherine's women." (95)

Reign of Edward VI

Henry VIII died on 28th January, 1547. During his 38-year reign he had ordered the execution of eighty-one people for heresy. His son Edward was only nine years old and was too young to rule. In his will, Henry had nominated a Council of Regency, made up of 16 nobles and churchman to assist Edward VI in governing his new realm. It was not long before his uncle, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, emerged as the leading figure in the government and was given the title Lord Protector. Seymour had been a secret Protestant for several years and brought an end to the prosecution of heretics.

In May 1547 Bishop Stephen Gardiner wrote to the Duke of Somerset complaining about incidents of image-breaking and the circulation of protestant books. Gardiner urged Somerset to resist religious innovation during the royal minority. Somerset replied accusing Gardiner of scaremongering and warning him about his future behaviour. According to his biographer, C. D. C. Armstrong: "Gardiner had tried to counter religious innovation with four arguments: first, he warned of the inadvisability of change during a royal minority; second, he argued that innovation was contrary to Henry's express wishes; third, he raised technical and legal objections; and finally he offered theological objections." (96)

On 25th September 1547 Gardiner was summoned to appear before the Privy Council. Unhappy with his answers he was sent to Fleet Prison. Gardiner himself believed that he had been imprisoned in order to keep him away from the parliament that proceeded to repeal the Henrician religious legislation such as Act for the Advancement of the True Religion. He was released in January 1548, after the closure of parliament. During this period the Duke of Somerset rejected proposals for the execution of leading Roman Catholics. (97)

Although Edward's government was tolerant towards Protestants they disliked the more radical Anabaptists. It has been pointed out: "The Anabaptists not only objected to infant baptism, but also denied the divinity of Christ or said that he was not born to the Virgin Mary. They advocated a primitive form of Communism, denouncing private property and urging that all goods should be owned by the people in common." (98)

Joan Bocher had held Anabaptist views for many years. She distributed pamphlets, and expressed the opinion that Christ, the perfect God, had not been born as a man to the Virgin Mary. She was arrested and brought to trial before Bishop Nicholas Ridley and found guilty of heresy. Bocher's views upset both Catholics and Protestants. John Rogers, who had been involved in the publishing of English Bible that had been translated by William Tyndale, was brought in to persuade her to recant. After failing in his mission he declared that she should be burnt at the stake.

John Foxe, who had been active in opposing the burning of heretics during the reign of Henry VIII was very distressed that Joan Bocher was now to be burned under the Protestant government of Edward VI. Although he disagreed with her views he thought that the life of "this wretched woman" should be spared and suggested that a better way of dealing with the problem was to imprison her so that she could not propagate her beliefs. Rogers insisted that she must die. Foxe replied she should not be burned: "at least let another kind of death be chosen, answering better to the mildness of the Gospel." Rogers insisted that burning alive was gentler than many other forms of death. Foxe took Rogers' hand and said: "Well, maybe the day will come when you yourself will have your hands full of the same gentle burning." (99) Foxe was right as Queen Mary ordered Rogers to be burnt at the stake on 4th February, 1555. (100)

It has been claimed by Christian Neff that the 12-year-old King Edward at first refused to sign the death warrant. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer insisted that "she should be punished with death for her heresy according to the law of Moses".He is said to have told Cranmer with tears, "Cranmer, I will sign the verdict at your risk and responsibility before God’s judgment throne." Cranmer was deeply impressed, and he tried once more to induce her to recant but she still refused. (101)

Joan Bocher was burnt at Smithfield on 2nd May 1550. "She died still upbraiding those attempting to convert her, and maintaining that just as in time they had come to her views on the sacrament of the altar, so they would see she had been right about the person of Christ. She also asserted that there were a thousand Anabaptists living in the diocese of London." (102)

As a result of the Bocher case, a commission was formed in January 1551 to deal with Anabaptism and other religious groups considered to be promoting heresy. One of the first people to be arrested was George van Parris. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, Miles Coverdale and Nicholas Ridley were the judges at the trial of Parris. As he knew no English, Coverdale acted as interpreter. He was examined on his views, and most especially the belief that "God the Father is only God, and that Christ is not very God". His refusal to recant sealed his fate, and he was condemned for Arianism on 7th April. Parris was burnt alive on 25th April 1551. (103)

Reign of Mary Tudor

Edward VI died on 6th July, 1553. During his six-year reign only two people had been burnt at the stake. As soon as she gained power, Queen Mary ordered the arrests of the leading Protestants in England. When he was arrested Hugh Latimer, the former Bishop of Worcester, told the officer that Smithfield, the place where heretics were burned, "had long groaned for him". (104) Latimer was taken to the Tower of London. So many Protestants were arrested that Latimer had to share his apartment with Thomas Cranmer, Nicholas Ridley and John Bradford. (105) To their mutual comfort, they "did read over the new testament with great deliberation and painful study", discussing again the meaning of Christ's sacrifice, and reinforcing their opinions on the spiritual presence in the Lord's supper. (106)

John Rogers was accused of being a seditious preacher and the Privy Council ordered his arrest. Rogers stayed a prisoner in his house for five months. Some of his religious friends escaped to Europe but Rogers insisted on staying in London to defend his beliefs. On 27th January 1554 he was sent to Newgate Prison. His biographer, David Daniell, points out: "He (John Rogers) was not permitted to receive any stipend, though by law he was still incumbent of St Sepulchre. His wife and ten children were in desperate need. He remained in Newgate for a year, untried. In November or December 1554 he joined with his fellow prisoners in writing a letter to the queen, protesting against the illegality of their imprisonment and begging to be brought to trial." (107)

In December 1554 parliament re-enacted legislation permitting the execution of heretics, and on 22nd January 1555 John Rogers was put on trial before Bishop Stephen Gardiner. Rogers was accused of heresy in denying the Papal Supremacy over the Church and the Real Presence of Christ in the consecrated bread and wine of the Sacrament. Rogers was attacked for having a wife and eleven children. He defended his decision to marry by arguing that the Bible did not say that priests should not have a wife. Rogers was also criticised for "misusing the gifts of learning which God had given them by arguing for a wicked cause against God's truth". (108)

John Rogers was found guilty of heresy. Rogers told the commissioners that he had only one request to make, and asked that before he was burned he should be permitted to receive one farewell visit from his wife. His request was denied and on 4th February 1555 he was degraded by Bishop Edmund Bonner. (109) This process has been explained by Jasper Ridley, the author of Bloody Mary's Martyrs (2002): "The hands were scraped with a knife to remove the holy oil with which they had been anointed. The scraping could be done either gently or roughly. The Protestants alleged that Bonner did it roughly whenever he took part in a degradation ceremony; but this may have been Protestant propaganda, for Bonner's attitude varied between boisterous and aggressive gloating and a patient attempt to persuade heretics to recant so that their lives could be spared." (110)

On 4th February, 1555, John Rogers was taken to Smithfield. His wife and children met him on the way to the burning, but Rogers still refused to recant. He told Sheriff Woodroofe: "That which I have preached I will seal with my blood." Woodroofe replied: "Then, you are a heretic. That will be known on the day of judgment." Just before the burning began a pardon arrived. However, Rogers refused to accept it and became the first martyr to suffer death during the reign of Queen Mary. (111)

It was claimed that when the fire took hold of his body, "he, as one feeling no smart, washed his hands in the flame, as though it had been in cold water" and "lifting up his hands to heaven he did not move them again until they were consumed in the devouring fire". (112) Protestants rejoiced in his faithfulness and even Catholic opponents noted his heroic fortitude in death. (113)

On 30th June 1555 John Bradford was told he was to executed the following day. "Thank God" he replied. "I've looked forward to this for a long time. The lord make me worthy." His execution was announced for four o'clock the next morning. "No one was sure why such an unusual hour was chosen, but if the authorities hoped the hour would discourage a crowd, they were disappointed. The people waited faithfully at Smithfield until Bradford was brought there at nine in the morning, led by an unusually large number of armed guards. Bradford fell to the ground to say his prayers then went cheerfully to the stake." (114)

Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley were moved to the Bocardo Prison in Oxford. By the time of his trial at the end of September 1555, Latimer complained that he had been kept "so long to the school of oblivion" with only "bare walls" for a library, that he could not defend himself adequately. (115) Unrepentant he unleashed upon his audience a categorical attack against the Catholic Church, which he characterized as "the traditional enemy of the true, persecuted flock of Christ". (116)

Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley were sentenced to be burnt at the stake for heresy on 16th October, 1555. John Foxe recalled that Latimer followed Ridley to the stake in Oxford in "a poor Bristol style frock all worn" and underneath a new shroud hanging down to his feet. Ridley was burnt first and Foxe recorded Latimer's defiant proclamation: "Be of good comfort Master Ridley, and play the man: we shall this day light such a candle by God's grace in England, as I trust shall never be put out". Foxe claimed that after Latimer "stroked his face with his hands, and as it were bathed them a little in the fire, he soon died with very little pain."

Nicholas Ridley took some time to die: "Ridley, by reason of the evil making of the fire unto him... burned clean all his nether parts before it touched the upper... Yet in all this torment he forgot not to call upon God... Let the fire come to me, I cannot burn. In which pains he laboured, till one of the standers by with his bill, pulled the faggots above, and when he saw the fire flame up, he wrested himself into that side. And when the flame touched the gunpowder, he was seen to stir no more." (117)

In November 1555 Thomas Cranmer, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote to Queen Mary urging her to assert and defend her royal supremacy over the Church of England and not to submit to the domination of the Bishop of Rome. When Mary received the letter she said that she considered it a sin to read, or even to receive, a letter from a heretic, and handed the letter to Archbishop Reginald Pole for him to reply to Cranmer. "There could have been nothing more painful for Cranmer, after he had appealed to his Queen to assert her royal supremacy against the foreign Pope, than to receive a reply from the Bishop of Rome's Legate informing him that the Queen had asked him to reply to Cranmer's letter to her." (118)

Cranmer was guarded by Nicholas Woodson, a devout Catholic, who attempted to persuade him to change his views. It has been claimed that this friendship came to be his only emotional support, and, to please Woodson, he began giving way to everything that he had hated. On 28th January, 1556, he signed his first hesitant submission to papal authority. This was followed by submissions on 14th, 15th and 16th February. On 24th February he was made aware that his execution would take place in a few days time. In an attempt to save his life, he signed a statement that was truly a recantation. He probably did not write it himself; the Catholic commentary on it merely says that Cranmer was ordered to sign it. (119)

Despite these recantations, Queen Mary I refused to pardon him and ordered Thomas Cranmer to be burnt at the stake. When he was told the news he probably remembered what Henry VIII said to him when he successfully persuaded the king not to execute his daughter. According to Ralph Morice Henry warned Cranmer that he would live to regret this action. (120)

On 21st March, 1556, Thomas Cranmer was brought to St Mary's Church in Oxford, where he stood on a platform as a sermon was directed against him. He was then expected to deliver a short address in which he would repeat his acceptance of the truths of the Catholic Church. Instead he proceeded to recant his recantations and deny the six statements he had previously made and described the Pope as "Christ's enemy, and Antichrist, with all his false doctrine." The officials pulled him down from the platform and dragged him towards the scaffold. (121)

Cranmer had said in the Church that he regretted the signing of the recantations and claimed that "since my hand offended, it will be punished... when I come to the fire, it first will be burned." According to John Foxe: "When he came to the place where Hugh Latimer and Ridley had been burned before him, Cranmer knelt down briefly to pray then undressed to his shirt, which hung down to his bare feet. His head, once he took off his caps, was so bare there wasn't a hair on it. His beard was long and thick, covering his face, which was so grave it moved both his friends and enemies. As the fire approached him, Cranmer put his right hand into the flames, keeping it there until everyone could see it burned before his body was touched." Cranmer was heard to cry: "this unworthy right hand!" (122)

It was claimed that just before he died Thomas Cranmer managed to throw the speech he intended to make in St Mary's Church into the crowd. A man whose initials were J.A. picked it up and made a copy of it. Although he was a Catholic, he was impressed by Cranmer's courage, and decided to keep it and it was later passed on to John Foxe, who published in his Book of Martyrs.

Jasper Ridley has argued that as a propaganda exercise, Cranmer's death was a disaster for Queen Mary. "An event which has been witnessed by hundreds of people cannot be kept secret and the news quickly spread that Cranmer was repudiated his recantations before he died. The government then changed their line; they admitted that Cranmer had retracted his recantations were insincere, that he had recanted only to save his life, and that they had been justified in burning him despite his recantations. The Protestants then circulated the story of Cranmer's statement at the stake in an improved form; they spread the rumour that Cranmer had denied at the stake that he had ever signed any recantations, and that the alleged recantations had all been forged by King Philip's Spanish friars." (123)

Queen Mary died, aged forty-two, on 17th November 1558. John Foxe has argued: "No other king or queen of England spilled as much blood in a time of peace as Queen Mary did in four years through her hanging, beheading, burning, and imprisonment of good Christian Englishmen. When she first sought the crown and promised to retain the faith and religion of Edward, God went with her and brought her the throne through the efforts of the Protestants. But after she broke her promises to God and man, sided with Stephen Gardiner, and gave up her supremacy to the pope, God left her. Nothing she did after that thrived." (124)

| Number of people executed for heresy in England and Wales. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Monarch | Date | Executed |

| Henry VII | 1485-1509 | 24 |

| Henry VIII | 1509-1547 | 81 |

| Edward VI | 1547-1553 | 2 |

| Mary | 1553-1558 | 283 |

| Elizabeth | 1558-1603 | 4 |

During Mary's reign that lasted for forty-five months, 283 Protestants - 227 men and 56 women - were burned alive. This was twice the number that had been burned in the previous 150 years. As Jasper Ridley has pointed out, this had long-term consequences for British history: "Queen Mary Tudor... has gone down in history as 'Bloody Mary', and her Roman Catholic co-relgionists still suffer, at least in some respects, because of what she did to the martyrs. It is impossible for a King or Queen of England to be a Roman Catholic or to marry a Roman Catholic; and Bloody Mary is indirectly responsible for the hatred of 'Papist' felt by the Protestants in Northern Ireland today. It was chiefly because the English and Irish Protestants remembered her martyrs that 130 years later, in 1688, they refused to accept a Roman Catholic king and to grant religious toleration to Roman Catholics. This led to the siege of Londonderry, the Battle of the Boyne, and the events of 1690 which are remembered with such disastrous results in Northern Ireland today." (125)

Queen Elizabeth and Heretics

Queen Elizabeth reappointed to her Privy Council most of the lords who had been in Mary's Privy Council who had dutifully persecuted Protestants. One of her first acts was to appoint Sir William Cecil as her Secretary. He had previously worked for Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, the Lord Protector during the reign of Edward VI. This was a clear indication that she wanted to create a society that was going to be more tolerant of those who had rebelled against the Roman Catholic Church. (126)

At the time she took power, there were Protestants in London and Salisbury, who had been condemned as heretics and were waiting to be burned. Elizabeth refused to sign their death warrants and they were released. However, she showed no interest in punishing those who had taken part in the burnings. Protestants in Guernsey attempted to prosecute Helier Gosselin who had organised the execution of three women on 18th July 1556.

Perotine Massey and her sister, Guillemine Gilbert, and their mother, Katharine Cawches, were charged with receiving a stolen goblet. At their trial it was decided that the main witness, Vincent Gosset, had lied about the goblet. The women were found not guilty and Gosset had his ear nailed to the pillory. During the trial it was recorded that the three women had not been attending church. According to the court report: "Master Dean and justices in your court and jurisdiction, after all amiable recommendations, pleaseth you to know that we are informed by the depositions of certain honest men, passed before us in manner of an inquiry; in the which inquiry Katharine Cawches and her two daughters have submitted themselves in a certain matter criminal: wherein we be informed that they have been disobedient to the commandments and ordinances of the church, in contemning and forsaking the mass and the ordinances of the same, against the will and commandment of our sovereign lord the king and the queen." All three women were charged with heresy and on 1st July 1556 taken to Castle Cornet. (127)

On 4th July, Perotine Massey, Guillemine Gilbert, and Katharine Cawches were tried for heresy. The women claimed that they had been acting according to the religious policies of King Edward VI. However, according to the testimony of their neighbours, they had been unwilling to follow the religious ceremonies that had been imposed by Queen Mary. All three women were found guilty of heresy and condemned to be burnt at the stake. Perotine was pregnant. In pagan times pregnant women could not be executed, but Catholics in the sixteenth century thought it was acceptable to kill the unborn.

Helier Gosselin was placed in charge of the executions that took place on 18th July 1556. All three were burnt on the same fire. John Foxe later recorded the deaths of the three women: "The time then being come, when these three good servants and holy saints of God, the innocent mother with her two daughters, should suffer, in the place where they should consummate their martyrdom were three stakes set up. At the middle post was the mother, the eldest daughter on the right hand, the youngest on the other. They were first strangled, but the rope brake before they were dead, and so the poor women fell in the fire. Perotine, who was then great with child, did fall on her side, where happened a rueful sight, not only to the eyes of all that there stood, but also to the ears of all true-hearted Christians that shall read this history. For as the belly of the woman burst asunder by the vehemence of the flame".

One of the witnesses to the execution, William House, took the baby from the fire and was laid upon the grass. Helier Gosselin ordered that "it should be carried back again, and cast into the fire". In his book, Book of Martyrs (1563), Foxe argued: "And so the infant, baptized in his own blood, to fill up the number of God's innocent saints, was both born and died a martyr, leaving behind to the world, which it never saw, a spectacle wherein the whole world may see the Herodin cruelty of.... catholic tormentors." (128) As the dead mother's uncle later complained in one of the surviving records of the incident "the baby born of one of them being taken up and cast into the fire again, four being executed, though only three had been condemned." (129)

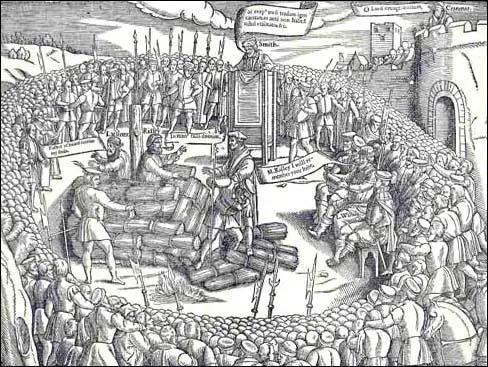

stake. An illustration from Foxe's Book of Martyrs (1563)

Protestants in Guernsey attempted to prosecute Helier Gosselin for the execution of Perotine Massey's baby. As the baby had not been condemned as a heretic, it was argued that the Gosselin was guilty of murder. Elizabeth was reluctant to become involved in punishing the people who had taken part in the burning of 283 Protestants during Mary's reign and decided to pardoned Gosselin. (130)

On 20th November, 1558, the first Sunday of the new reign, Dr. William Bill, Elizabeth's almoner, preached at St Paul's Cross. "This was the most important pulpit in the kingdom, and was regularly used as the sounding board for government religious policy." (131) Dr. Bill, who had been the Master of Trinity College during the reign of Edward VI but had been ejected from the post by Roman Catholic fellows of the college, when Mary became Queen of England. Elizabeth instructed Dr. Bill to say, in his sermon, that the Protestants would not make any alteration in religion until the Queen authorised it. (132)

Elizabeth allowed Mary to have a splendid Catholic funeral that took place on 14th December, 1558. Bishop John White preached the sermon. He chose as his text: "I praise the dead more than the living", and did not disguise the fact that he was favourably comparing the dead Queen Mary with the living Queen Elizabeth. The main theme of his sermon was to warn against change, John Jewel, later Bishop of Salisbury, described the sermon as "very seditious". White lost his post but was not imprisoned or burnt as a heretic. (133)

Bishop Owen Oglethorpe, celebrated Mass for Elizabeth in her chapel royal at Whitehall at Christmas 1558. She ordered him not to elevate the Host for adoration. He refused to comply with her instructions, and elevated it; so she walked out of the chapel in protest. As has been pointed out, any woman who had done this six weeks earlier would have been burned as a heretic. (134) Oglethorpe was not punished and was allowed to officiate at her coronation on 15th January 1559. (135)

Elizabeth's first Parliament met in March 1559. She asked it to pass legislation repudiating Papal supremacy, and acknowledging the Queen as Supreme Governor of the Church of England. Another bill made it a criminal offence to celebrate or attend Mass, punishable by imprisonment for six months for the first offence, twelve months for the second offence, and for life for the third offence. These bills were opposed by the bishops in the House of Lords, including Bishop Edmund Bonner, who had been allowed to keep his post despite the fact that he had played a leading role in the persecution of Protestants. (136) John Foxe claimed that about 200 were personally tried and sentenced by him. (137)

In the House of Commons Elizabeth's main opponent was John Story, who had played so prominent a part in the interrogation of several heretics, as well as having been one of the counsel for the prosecution at the trial of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer. Story defended the part he had played in persecuting heretics under Mary: "I wish for my part that I had done more that I did. I threw a faggot in the face of an earwig at the stake at Uxbridge as he was singing a psalm, and set a bushel of thorns under his feet... and I see nothing to be ashamed of, nor sorry for." Story then went on to say that he had told Queen Mary that she was only prosecuting the common people by "chopping at twigs". Story explained that he "wished to have chopped at the roots, which if they had done, this gear had not come now in question". Virtually everyone who heard the debate thought that Story meant that the Catholics should have burned Princesses Elizabeth. (138)

The bill abolishing Papal supremacy, and acknowledging the Queen as Supreme Governor of the Church of England passed the House of Lords by thirty-three votes to twelve with all the bishops voting against it. The bill abolishing the Mass and imposing the Third Book of Common Prayer passed by a majority of three. On the day it came into force Bishop Edmund Bonner celebrated Mass in St Paul's Cathedral. He was imprisoned but not tried as a heretic.

John Story went to live in Spain and took part in the persecution of heretics. He also attempted to persuade Spain to invade England. Story was kidnapped and brought back to England and was prosecuted for "stirring foreigners to invade the queen's dominions and of compassing war against her abroad". Story was found guilty of high treason and was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. He was executed on 1st June, 1571. (139)

In 1575 a congregation of Anabaptists were discovered in Aldgate. Although they were of Dutch nationality they were tried before Edwin Sandys, the bishop of London in St Paul's Cathedral for heresy and blasphemy. Some of them recanted and were allowed to go free after parading the streets with lighted faggots in their hands. Fifteen of them were deported and five were condemned to death by burning. (140)

Only their two leaders, John Weelmaker and Henry Toorwoort, were actually ordered to be burnt at the stake at Smithfield. John Foxe attempted to save them. He later stated that he was disappointed that Elizabeth had not introduced "religious liberty" but acknowledged that she was not cruel monarch and did appear to have an "aversion to bloodshed". (141)

The Tudor historian, John Stow, says that Weelmaker and Toorwoort died "with great horror, crying and roaring". James Mackintosh, the 19th century historian, commented: "This murder, as far as the multitude thought of it, met with their applause. It was considered by others as the ordinary course. But the first blood spilt by Elizabeth for religion forms in the eye of posterity a dark spot upon a government hitherto distinguished, beyond that of any other European community, by a religious administration, which, if not unstained, was at least bloodless." (142)

Elizabeth did allow Catholic priests to be tortured. John Gerard suffered this ordeal in 1594: "The torture chamber was underground and dark... every device and instrument of torture was there... They left me hanging by my hands and arms fastened above my head... a gripping pain came over me... All the blood in my body seemed to rush up into my arms and hands and I thought the blood was oozing out from the ends of my fingers and the pores of my skin. But was only a sensation caused by my flesh swelling above the irons holding them... The warder went on and on, begging and imploring me to pity myself and tell the gentleman what they wanted to know." (143)

Primary Sources

(1) John Gerard was a Catholic priest who was tortured in the Tower of London on 14 April 1597.

The torture chamber was underground and dark... every device and instrument of torture was there... They left me hanging by my hands and arms fastened above my head... a gripping pain came over me... All the blood in my body seemed to rush up into my arms and hands and I thought the blood was oozing out from the ends of my fingers and the pores of my skin. But was only a sensation caused by my flesh swelling above the irons holding them... The warder went on and on, begging and imploring me to pity myself and tell the gentleman what they wanted to know... More than once I interrupted him, "Stop this talk, for heaven's sake. Do you think I'm going to throw my soul away to save my life?"

(2) On 21 March 1556, Thomas Cranmer, the first Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury was executed for heresy. An eyewitness in the crowd described his death.

Coming to the stake... he put off his garments with haste, and stood upright in his shirt The fire was lit... he stretched out his right hand, and thrust it into the flame, and held it there before the flame came to any other part of the body... As soon as the fire got up, he was very soon dead, never stirring or crying all the while.

(3) Rowland Lea worked in the Tower of London during Lady Jane Grey's imprisonment. In his diary, Rowland Lea described the execution of Lady Jane Grey on the green within the walls of the Tower of London.

Lady Jane was calm, although . Elizabeth and Ellen wept... The executioner kneeled down and asked for forgiveness, which she gave most willingly... she said: "I pray you dispatch me quickly." She tied a handkerchief over her eyes; then feeling for the block, she said, "What shall I do? Where is it?" One of the bystanders guided her... She laid down her head upon the block, and stretched forth her body.

(4) While she was in the Tower of London, the Protestant, Anne Askew, wrote her own account of being tortured. A copy of this account was then smuggled out to her friends. (29 June, 1546)