Thomas Wriothesley

Thomas Wriothesley, the son of William Wriothesley and Agnes Drayton, was born in 1505. Agnes gave birth to three more children, Elizabeth (1507), Anne (1508) and Edward (1509).

Michael A. R. Graves has pointed out: "It was a sign of the family's rising status and fortunes that Edward Stafford, third duke of Buckingham, and Henry Percy, fifth earl of Northumberland, were godfathers at Edward's baptism." (1) Wriothesley was educated at St Paul's School, London, where his contemporaries included John Leland, Anthony Denny and William Paget. In about 1522 he went to Trinity Hall, Cambridge, where one of his teachers was Stephen Gardiner. A fellow student was his cousin, Charles Wriothesley. However, he left without taking a degree. (2)

In 1524, Wriothesley, when only nineteen, went to work for Thomas Cromwell. whom he styled his master and from that date many documents from the Cromwell office are in his handwriting. In 1530 he was a clerk under Bishop Gardiner, who was now the king's secretary. He remained in that post for a decade and during that time he also continued to serve Cromwell. In December 1532 Wriothesley was sent to Brussels with dispatches, and in October 1533 royal service took him to Marseilles.

Thomas Wriothesley and Thomas Cromwell

In 1533 Thomas Wriothesley married Jane Cheney. Thomas and Jane had three sons: William, Anthony and Henry and five daughters: Elizabeth, Mary, Katherine, Anne, and Mabel. William and Anthony both died in childhood. In 1534 Wriothesley was admitted to Gray's Inn.

In January 1535, Thomas Cromwell was appointed as Vicar-General. This made him the King's deputy as Supreme Head of the Church. On 3rd June he sent a letter to all the bishops ordering them to preach in support of the supremacy, and to ensure that the clergy in their dioceses did so as well. A week later he sent further letters to Justices of Peace ordering them to report any instances of his instructions being disobeyed. In the following month he turned his attention to the monasteries. In September he suspended the authority of every bishop in the country so that the six canon lawyers he had appointed as his agents could complete their surveys of the monasteries. (3)

The survey revealed that the total annual income of all the monasteries was about £165,500. The eleven thousand monks and nuns in this institutions also controlled about a quarter of all the cultivated land in England. The six lawyers provided detailed reports on the monasteries. According to David Starkey: "Their subsequent reports concentrated on two areas: the sexual failings of the monks, on which subject the visitors managed to combine intense disapproval with lip-smacking detail, and the false miracles and relics, of which they gave equally gloating accounts." (4)

A Parliament was called in February 1536 to discuss these reports. With the encouragement of Cromwell they agreed to pass the Act for the Dissolution of Monasteries. This stated that all religious houses with an annual income of less than £200 were to be "suppressed". Thomas Wriothesley played an important role in this. This included the destruction of St Swithin's shrine and the removal of all relics and treasure at Winchester Cathedral. (5)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A total of 419 monastic houses were obliged to close but the abbots made petitions for exemptions, and 176 of the monasteries were allowed to stay open. It is believed that Cromwell was bribed in money and goods to reach this agreement. (6) Monastery land was seized and sold off cheaply to nobles and merchants. They in turn sold some of the lands to smaller farmers. This process meant that a large number of people had good reason to support the monasteries being closed. These actions brought him into conflict with his mentor, Bishop Stephen Gardiner.

Over the next few years Wriothesley acquired, chiefly through royal grant, former monastic manors and religious houses in eight counties, as well as three houses and a manor in London. "The nucleus of his estates was in Hampshire: Quarr Abbey on the Isle of Wight (granted in 1537); the eleven manors and 5000 acres of Titchfield Abbey (1537); Beaulieu Abbey (1538)... Wriothesley made Titchfield the centre of his domain and transformed the buildings into a residence befitting the rising bureaucrat and courtier." (7)

In April 1540 Thomas Cromwell arranged for Thomas Wriothesley and Ralph Sadler to be appointed as Privy Councillors. (8) Cromwell was involved in a power struggle with with Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk. On 10th June, Cromwell arrived slightly late for a meeting of the Privy Council. Norfolk shouted out, "Cromwell! Do not sit there! That is no place for you! Traitors do not sit among gentlemen." The captain of the guard came forward and arrested him. (9) Cromwell was charged with treason and heresy. Norfolk went over and ripped the chains of authority from his neck, "relishing the opportunity to restore this low-born man to his former status". Cromwell was led out through a side door which opened down onto the river and taken by boat the short journey from Westminster to the Tower of London. (10)

Cromwell was convicted by Parliament of treason and heresy on 29th June and sentenced him to be hung, drawn and quartered. He wrote to Henry VIII soon afterwards and admitted "I have meddled in so many matters under your Highness that I am not able to answer them all". He finished the letter with the plea, "Most gracious prince I cry for mercy, mercy, mercy." Henry commuted the sentence to decapitation, even though the condemned man was of lowly birth. (11) Cromwell was executed on 28th July, 1540.

Lord Chancellor

Wriothesley was taken into custody but was released without charge. He now rejected the religious policies of Cromwell and returned to orthodox beliefs of Bishop Stephen Gardiner and became involved in the persecution of the heretics. He also helped to provide evidence of adultery against Catherine Howard. Wriothesley examined and extracted confessions from her music teacher Henry Manox and the courtier Francis Dereham. (12)

On 29th January 1543, Wriothesley became joint chamberlain of the exchequer. Henry VIII used him for several diplomatic missions and was involved in negotiations with Charles V, that resulted in a joint invasion of France. In July, 1544, Henry VIII led a military expedition to France. "During his absence Henry appointed his queen regent-general, together with a regency council dominated by the queen's fellow religionists.... This assumption of power, not merely by a woman but by a woman who only a year before had been a Yorkshire housewife, made the queen enemies, particularly among the religious conservatives who resented her evangelical beliefs." (13) Wriothesley was appointed to the Regency Council during this period.

After the death of Thomas Audley, Wriothesley was appointed as Lord Chancellor. He began to carry out an investigation into the religious reform movement. Eustace Chapuys reported that "the two people who enjoy nowadays most authority and have the most influence and credit with the king", the official "who enjoys most credit" with Henry, and the man "who nowadays… almost governs everything here". Wriothesley was granted thirty-five ex-monastic manors in Hampshire and was elevated to the peerage as Baron Wriothesley of Titchfield. (14)

Thomas Wriothesley was an "ardent in his pursuit of those heretics with connections to the court". (15) This included examining the activities of Queen Catherine Parr, who had written several small books on religious matters. It has been pointed out that Catherine was one of only eight women who had books published in the sixty-odd years of the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII. These books showed that she was an advocate of Protestantism. In the book, The Lamentation of a Sinner Catherine describes Henry as being "godly and learned" and being "our Moses" who "hath delivered us out of the captivity and bondage of Pharaoh (Rome)"; while the "Bishop of Rome" is denounced for "his tyranny".

As David Loades, the author of has pointed out, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (2007): "The Queen meanwhile continued to discuss theology, piety and the right use the bible, both with her friends and also with her husband. This was a practice, which she had established in the early days of their marriage, and Henry had always allowed her a great deal of latitude, tolerating from her, it was said, opinions which no one else dared to utter. In taking advantage of this indulgence to urge further measures of reform, she presented her enemies with an opening." (16)

Catherine also criticised legislation that had been passed in May 1543 that had declared that the "lower sort" did not benefit from studying the Bible in English. The Act for the Advancement of the True Religion stated that "no women nor artificers, journeymen, serving men of the degree of yeomen or under husbandmen nor labourers" could in future read the Bible "privately or openly". Later, a clause was added that did allow any noble or gentlewoman to read the Bible, this activity must take place "to themselves alone and not to others". Catherine ignored this "by holding study among her ladies for the scriptures and listening to sermons of an evangelical nature". (17)

Persecution of Heretics

In February 1546 conservatives, led by Thomas Wriothesley and Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, began plotting to destroy Catherine Parr. Gardiner had established a reputation for himself at home and abroad as a defender of orthodoxy against the Reformation. (18) On 24th May, Gardiner ordered the arrest of Anne Askew and Sir Anthony Kingston, the Constable of the Tower of London, was ordered to torture Askew in an attempt to force her to name Catherine and other leading Protestants.

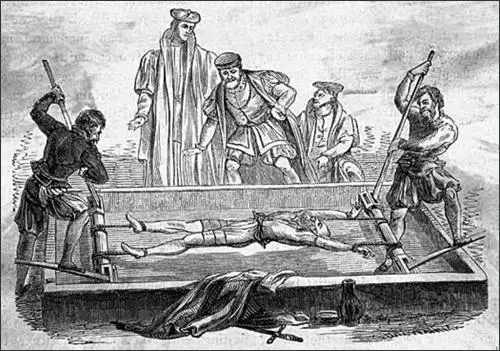

Thomas Wriothesley and his assistant, Richard Rich took over operating the rack, after Kingston complained about having to torture a woman. Despite suffering a long period on the rack, Askew refused to name those who shared her religious views. According to Askew: "Then they did put me on the rack, because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen, to be of my opinion... the Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands, till I was nearly dead. I fainted... and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours arguing with the Lord Chancellor, upon the bare floor... With many flattering words, he tried to persuade me to leave my opinion... I said that I would rather die than break my faith." (19) On 16th July, 1546, Askew "still horribly crippled by her tortures but without recantation, was burnt for heresy". (20)

Thomas Wriothesley's biographer, Michael A. R. Graves, has pointed out: "Wriothesley's prominence in government meant that he was actively employed in enforcing the conservative religious policy of Henry's final years. Rich, Bonner, Wriothesley, and especially Gardiner were prominent among the royal servants, some of them rigorous Catholic conformists, who sought to expose and punish not only individual evangelicals but also their support networks of friends, followers, patrons, and protectors, especially in the court. ... Anne Askew was executed as the decline of Henry VIII's health was causing politicians increasingly to prepare themselves for the next reign. Wriothesley's exact religious position is seldom clear, and may well have been subordinated to his temporal aspirations." (21)

Bishop Stephen Gardiner had a meeting with Henry VIII and raised concerns about Catherine's religious beliefs. Henry, who was in great pain with his ulcerated leg and at first he was not interested in Gardiner's complaints. However, eventually Gardiner got Henry's agreement to arrest Catherine and her three leading ladies-in-waiting, "Herbert, Lane and Tyrwhit" who had been involved in reading and discussing the Bible. (22)

David Loades has explained that "the greatest secrecy was observed, and the unsuspecting Queen continued with her evangelical sessions". However, the whole plot was leaked in mysterious circumstances. "A copy of the articles, with the King's signature on it, was accidentally dropped by a member of the council, where it was found and brought to Catherine, who promptly collapsed. The King sent one of his physicians, a Dr Wendy, to attend upon her, and Wendy, who seems to have been in the secret, advised her to throw herself upon Henry's mercy." (23)

Catherine told Henry that "in this, and all other cases, to your Majesty's wisdom, as my only anchor, Supreme Head and Governor here in earth, next under God". He reminded her that in the past she had discussed these matters. "Catherine had an answer for that too. She had disputed with Henry in religion, she said, principally to divert his mind from the pain of his leg but also to profit from her husband's own excellent learning as displayed in his replies." (24) Henry replied: "Is it even so, sweetheart? And tended your arguments to no worse end? Then perfect friends we are now again, as ever at any time heretofore." (25) Gilbert Burnett has argued that Henry put up with Catherine's radical views on religion because of the good care she took of him as his nurse. (26)

The next day Thomas Wriothesley arrived with a detachment of soldiers to arrest Catherine. Henry told him he had changed his mind and sent the men away. Glyn Redworth, the author of In Defence of the Church Catholic: The Life of Stephen Gardiner (1990) has disputed this story because it relies too much on the evidence of John Foxe,, a leading Protestant at the time. (27). However, David Starkey, the author of Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (2003) has argued that some historians "have been impressed by the wealth of accurate circumstantial detail, including, in particular, the names of Catherine's women." (28)

Henry VIII died on 28th January 1547. Thomas Wriothesley was one of the sixteen executors of the regency council who acted as guardians to Edward VI and were entrusted with the government of the realm. On 16th February, he was created earl of Southampton with an annual allowance of £20. However, it was not long before Edward's uncle, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, emerged as the leading figure in the government and Wriothesley lost his post as Lord Protector. Seymour, a supporter of the Protestants that Wriothesley had been prosecuting, had him arrested. However, he was released without punishment on 29th June. He was also allowed to attend Parliament. (29)

Thomas Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, died on 30th July 1550.

Primary Sources

(1) Alison Plowden, Tudor Women (2002)

Since her marriage the Queen had undoubtedly moved steadily further towards Protestantism, and in the summer of 1546 her enemies at last saw an opportunity to pounce. In her little book of prayers and meditations, The Lamentation of a Sinner, which had recently been circulating in manuscript form, Katherine reminded her own sex that: `if they be women married, they learn of St Paul to be obedient to their husbands, and to keep silence in the congregation, and to learn of their husbands at home'. Unfortunately, there was to be an occasion towards the end of June 1546 when the Queen failed to follow this excellent advice - at least according to the story later told by John Foxe in his best-selling Book of Martyrs. Henry's dancing days were over now, and it was his wife's habit to sit with him in the evenings and endeavour to entertain him and take his mind off the pain of his ulcerated legs by inaugurating a

discussion on some serious topic, which inevitably meant some religious topic. On this particular occasion, Katherine seems to have allowed her enthusiasm to run away with her, and the King was provoked into grumbling to Stephen Gardiner: "A good hearing it is, when women become such clerks, and a thing much to my comfort to come in mine old days to be taught by my wife."This, of course, was Gardiner's cue to warn his sovereign lord that he had reason to believe the Queen was deliberately undermining the stability of the state by fomenting heresy of the most odious kind and encouraging the lieges to question the wisdom of their prince's government. So much so, that the Council was "bold to affirm that the greatest subject in this land, speaking those words that she did speak and defending likewise those arguments that she did defend, had with impartial justice by law deserved death". Henry was all attention. Anything which touched the assurance of his own estate was not to be treated lightly, and he authorized an immediate enquiry into the orthodoxy of the Queen's household, agreeing that if any evidence of subversion were forthcoming, charges could be brought against Catherine herself.

Gardiner and his ally on the Council, the Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley, planned to attack the Queen through her ladies and believed they possessed a valuable weapon in the person of Anne Kyme, better known by her maiden name of Anne Askew, a notorious heretic already convicted and condemned. Anne, a truculent and argumentative young woman who came from a well-known Lincolnshire family, had left her husband and come to London to seek a divorce. Quoting fluently from the Scriptures, she claimed that her marriage was to longer valid in the sight of God, for had not St Paul written: "If a faithful woman have an unbelieving husband, which will not tarry with her she may leave him"? (Thomas Kyme was an old-fashioned Catholic who objected strongly to his wife's Bible-punching propensities.)

Anne failed to get her divorce, but her zeal, her sharp tongue and her lively wit soon made her a well; known figure in Protestant circles. Inevitably she soon came up against the law, and In March 1546 she was arrested on suspicion of heresy, specifically on a charge of denying the Real Presence in the sacrament of the altar. Pressed by Bishop Bonner on this vital point, Anne hesitated and was finally persuaded to sign a confession which amounted to an only slightly qualified statement of orthodox belief. A few days later she was released from gaol and went home to Lincolnshire - not to her husband but to her brother Sir Francis Askew.

Throughout that spring the conservative counter-attack gathered momentum, and by early summer a vigorous anti-heresy drive was in progress. At the end of May Thomas Kyme and his wife were summoned to appear before the Council. Although not proved, it's probable that the initiative for this move came from Kyme himself. Anne had refused to obey the order of the Court of Chancery to return to him, nor is it likely that he wanted her back. At the same time, he was in an invidious position, deserted-and defied by his wife and unable to marry again. It cannot have failed to occur to him that only Anne's death would finally solve his problems. Armed with a royal warrant and backed up by the Bishop of Lincoln (who had a long score to settle with Anne), Thomas Kyme forcibly removed her from her brother's protection and carried her off to London.

The Council's summons was ostensibly about the matrimonial issue, and Kyme was soon dismissed, but Anne, `for that she was very obstinate and heady in reasoning of matters of religion, wherein she avowed herself to be of a naughty opinion', was committed to Newgate prison to face renewed heresy charges. All through the following week determined efforts were made to wring from her a second and more complete recantation. The bishops were not anxious to make martyrs - retractions, especially from the better-known Protestants, would obviously be more valuable for propaganda purposes - but Anne was not to be caught a second time. When Stephen Gardiner tried his charm on her, begging her to believe he was her friend, concerned only with her soul's health, she retorted that that was just the attitude adopted by Judas "when he unfriendly betrayed Christ". Any lingering doubts and fears had passed. She knew now, with serene certainty, what Christ wanted from her, and she was ready to give it. At her trial on 28 June she flatly rejected the existence of any priestly miracle in the eucharist. "As for that ye call your God, it is a piece of bread. For a more proof thereof... let it but lie in the box three months and it will be mouldy." After that, there could be no question of the verdict, and sentence of death by burning was duly passed on this self-confessed and obstinate heretic.

Anne Askew is an interesting example often educated, highly intelligent, passionate woman destined to become the victim of the society in which she lived - a woman who could not accept her circumstances but fought an angry, hopeless battle against them. She was unquestionably sincere in her religious convictions - to what extent she also used them unconsciously to sublimate tensions and frustrations which might otherwise have been unbearable, we can only speculate. To Thomas Wriothesley the interesting thing about her was the fact that she was known to have close connections with the Court. Two of her brothers were in the royal service, and she was friendly with John Lassells - the same who had betrayed Katherine Howard five years before. It's highly probable that Anne had attended some of the Biblical study sessions in the Queen's apartments, and she was certainly acquainted with some of the Queen's ladies. If it could now be shown that any of these ladies - perhaps even the Queen herself- had been in touch with her since her recent arrest; if it could be proved that they had been encouraging her to stand firm in her heresy, then the Lord Chancellor would have ample excuse for an attack on Catherine Parr.

Anne was therefore transferred to the Tower, where she received a visit from Wriothesley and his henchman Sir Richard Rich, the Solicitor General, but the interview proved a disappointment. She denied having received any visits while she had been in prison, and no one had willed her to stick to her opinions. Her maid had been given ten shillings by a man in a blue coat who said that Lady Hertford had sent it, and eight shillings by another man in a violet coat who said it came from Lady Denny, but whether this was true or not she didn't know, it was only what her maid had told her.

Convinced that Anne could have given them a long list of highly-placed secret sympathizers, and infuriated perhaps by her air of stubborn righteousness, Wriothesley ordered her to be stretched on the rack. This was not only illegal without a proper authorization from the Privy Council, it was unheard of to apply torture to a woman, let alone a gentlewoman like Anne Askew with friends in the outside world, and the Lieutenant ant of the Tower hastily dissociated himself from the whole proceeding. As a result, there followed a quite unprecedented scene, with the Lord Chancellor of England stripping off his gown and personally turning the handle of the rack. It was a foolish thing to do. Anne told him nothing more, if indeed there was anything to tell, and, since the story of her constancy soon got about, he'd only succeeded in turning her into a popular heroine.

The plot against the Queen fizzled out, largely due to the King's intervention. He took care that Katherine should receive advance warning of what was being planned for her and gave her the opportunity to explain that of course she had never for one moment intended to lay down the law to him, her lord and master, her only anchor, supreme head and governor here on earth. It was preposterous - against the ordinance of nature - for any woman to presume to teach her husband; it was she who must be taught by him. As for herself, if she had ever seemed bold enough to argue, it had not been to maintain her own opinions but to encourage discussion so that he might `pass away the weariness of his present infirmity' and she might profit by hearing his learned discourse! Satisfied, the King embraced his wife, and an affecting reconciliation took place.

If any real evidence of treasonable heresy had been uncovered in the Queen's household - if Henry had seriously suspected that Catherine was connected with any group which planned to challenge his own mandate from Heaven-then this story might have ended differently. As it was, he'd apparently been sufficiently irritated to feel that it would do her no harm to be taught a lesson, to be given a fright and a sharp warning not to meddle in matters which were no concern of outsiders, however privileged. Katherine, with her usual good sense, took the warning to heart, and there's no mention of any further theological disputations, even amicable ones, between husband and wife.

The Queen was unable to save Anne Askew, but her martyrdom on 16 July 1546 marked the end of the conservative resurgence, and by the time of the old King's death in the following January the progressive party was once more taking the lead.

(2) David Loades, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (2007) page 140-141

Throughout his reign Henry had periodically displayed a compulsive need to demonstrate that he was in charge, and his brinkmanship over Cranmer's arrest may have been another example of that unlovable trait. If so, then the conservative position may have been less damaged by the debacle than appeared. In 1545 a Yorkshire gentlewoman named Anne Askew was arrested on suspicion of being a sacramentary. Her views were extreme, and pugnaciously expressed, so she would probably have ended at the stake in any case but her status gave her a particular value to the orthodox. This was greatly enhanced in the following year by the arrest of Dr Edward Crome, who, under interrogation, implicated a number of other people, both at court and in the City of London. Anne had been part of the same network, and she was now tortured for the purpose of establishing her links with the circle about the Queen, particularly Lady Denny and the Countess of Hertford. She died without revealing much of consequence, beyond the fact that she was personally known to a number of Catherine's companions, who had expressed sympathy for her plight. The Queen meanwhile continued to discuss theology, piety and the right use the bible, both with her friends and also with her husband. This was a practice, which she had established in the early days of their marriage, and Henry had always allowed her a great deal of latitude, tolerating from her, it was said, opinions which no one else dared to utter. In taking advantage of this indulgence to urge further measures of reform, she presented her enemies with an opening. Irritated by her performance on one occasion, the King complained to Gardiner about the unseemliness of being lectured by his wife. This was a heaven-sent opportunity, and undeterred by his previous failures, the bishop hastened to agree, adding that, if the King would give him permission he would produce such evidence that, "his majesty would easily perceive how perilous a matter it is to cherish a serpent within his own bosom". Henry gave his consent, as he had done to the arrest of Cranmer, articles were produced and a plan was drawn up for Catherine's arrest, the search of her chambers, and the laying of charges against at least three of her privy chamber.

The greatest secrecy was observed, and the unsuspecting Queen continued with her evangelical sessions. Henry even signed the articles against her. Then, however, the whole plot was leaked in mysterious circumstances. A copy of the articles, with the King's signature on it, was accidentally dropped by a member of the council, where it was found and brought to Catherine, who promptly collapsed. The King sent one of his physicians, a Dr Wendy, to attend upon her, and Wendy, who seems to have been in the secret, advised her to throw herself upon Henry's mercy. No doubt Anne Boleyn or Catherine Howard would have been grateful for a similar opportunity, but this was a different story. Seeking out her husband, the Queen humbly submitted herself, "... to your majesty's wisdom,, as my only anchor". She had never pretended to instruct, but only to learn, and had spoken to him of Godly things in order to ease and cheer his mind.

Henry, so that story goes, was completely disarmed, and a perfect reconciliation was affected, so that when Sir Thomas Wriothesley arrived at Whitehall the following day with an armed guard, he found all his suspects walking with the King in the garden, and was sent on his way with a fearsome ear-bending. Had the conservatives walked into another well-baited trap? As related by Foxe, the whole story has an air of melodramatic unreality about it, but it bears a striking resemblance to the two stories of Cranmer, which come from a different source. Whether Henry was playing games with his councillors in order to humiliate them, or with his wife in order to reassure himself of her submissiveness, or whether he was genuinely wavering between two courses of action, we shall probably never know. In outline the story is probably correct, and we may never be able to disentangle Foxe's embellishments. The consequences, in any case, were real enough. Gardiner finally lost the King's favour, and did not recover it, so that he was deliberately omitted from the regency council which Henry shortly after set up for his son's anticipated minority.

(3) While she was in the Tower of London, the Protestant, Anne Askew, wrote her own account of being tortured. A copy of this account was then smuggled out to her friends. (29th June, 1546)

Then they did put me on the rack, because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen, to be of my opinion... the Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands, till I was nearly dead. I fainted... and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours arguing with the Lord Chancellor, upon the bare floor... With many flattering words, he tried to persuade me to leave my opinion... I said that I would rather die than break my faith.

(4) John Foxe, Book of Martyrs (1563)

The Lord Chancellor sent to Anne Askew letters offering her the king's pardon if she would recant.. she refused... and thus the good Anne Askew ended the course of her long agonies and was burnt at the stake.

Student Activities

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)