On this day on 8th December

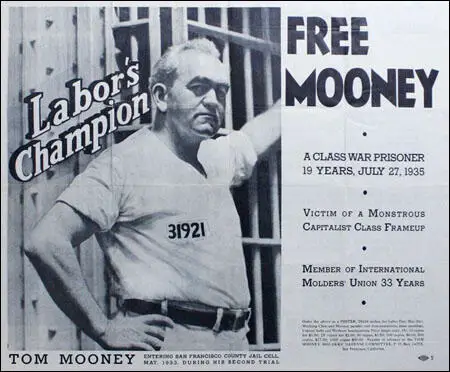

On the day in 1882 Tom Mooney, the son of Irish immigrants, was born in Chicago. Mooney's father was a coal miner who died of tuberculosis at the age of 36. When he was fourteen Mooney started work at a local factory. The following year he was apprenticed as an iron molder and in 1902 joined the International Molders Union. When he saved enough money Mooney went to Europe and visited Ireland, England, France, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Hungary, Switzerland and Italy. While in a Rotterdam art museum he met Nicholas Klein, an American who was in Europe for a meeting of the International Socialist Congress. By the time Mooney returned to the United States he was a committed socialist and had begun reading the works of Karl Marx.

In March 1908 Mooney found work as an iron molder in Stockton. Soon afterwards he joined the Socialist Party of America and played an active role in the presidential campaign of Eugene V. Debs. After the unsuccessful political campaign Mooney returned to Chicago where he spent twelve hours a day in the reference library reading books on socialism.

In 1909 Mooney found work in an Idaho iron foundry. The following year he represented his party at the International Socialist Congress in Copenhagen and met with leaders of the Labour Party in England. On his return he settled in San Francisco where he became a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Over the next few years Mooney became friendly with some of IWW's leading figures such as William Haywood, Mary 'Mother' Jones and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn.

Mooney married Rena Hermann in 1911. He also became the publisher of The Revolt, a socialist newspaper in San Francisco. The paper was a great success and acquired a circulation of 1,500. Mooney also ran as the Socialist Party of America candidate for Sheriff.

In September 1913 Mooney was asked by Edgar Hurley, a local trade unionist, to carry a suitcase from Oakland to Sacramento. Mooney had been set-up by Martin Swanson of the Pinkerton Detective Agency and when he arrived in Sacremento he was arrested and charged with transporting explosives illegally on a streetcar. He was convicted and sentenced to Folsom Penitentiary for two years.

Mooney was released on appeal and in 1914 he was active in the campaign to free Joe Haaglund Hill, a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Convicted of the murder of a Salt Lake City businessman, Hill was shot by a firing squad on 19th November, 1915.

Mooney also associated with the revolutionary anarchist Alexander Berkman. In 1916 Mooney helped Berkman launch the journal Blast. Contributors to the journal included Emma Goldman, Mary Heaton Vorse and Robert Minor. Unable to find work as a iron molder Mooney worked full-time as a union organizer. He became one of the leaders of the Californian Federation of Labor and in 1916 became involved in a strike of streetcar workers employed by the United Railroads (URR).

On 11th June a high-voltage tower of the Sierra and San Francisco Power Company, which served the URR, was dynamited in the San Bruno hills. Soon afterwards the URR offered a reward of $5,000 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the dynamiters. Martin Swanson, who now worked for the Public Utilities Protective Bureau, became convinced that Mooney was the man responsible for the bombing. On 13th June 1916 Swanson interviewed Israel Weinberg, a jitney bus driver who had often taken Mooney to trade union meetings. Swanson offered Weinberg a share of the $5,000 reward if he could provide evidence that would convict Mooney of the San Bruno bombing.

Soon afterwards Swanson approached Warren Billings, a trade union friend of Mooney. As well as a share of the $5,000 reward Billings was offered a job with the Pacific Gas and Electric Company if he could provide information connecting Mooney with the San Bruno bombing. Billings refused and reported the approach to Mooney and George Speed, the secretary of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

On 22nd July, 1916, employers in San Francisco organized a march through the streets in favour of an improvement in national defence. Critics of the march such as William Jennings Bryan, claimed that the Preparedness March was being organized by financiers and factory owners who would benefit from increased spending on munitions. During the march a bomb went off in Steuart Street killing six people (four more died later). Two witnesses described two dark-skinned men, probably Mexicans, carrying a heavy suitcase near to where the bomb exploded.

The Chamber of Commerce immediately offered a reward of $5,000 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the dynamiters. Other organizations and individuals added to this sum and the reward soon reached $17,000. Offering such a large reward was condemned by the editor of the New York Times claiming it was a "sweepstake for perjurers".

On the evening of the bombing Martin Swanson went to see the District Attorney, Charles Fickert. Swanson told Fickert that despite the claims that it was the work of Mexicans, he was convinced that Mooney and Warren Billings were responsible for the explosion. The next day Swanson resigned from the Public Utilities Protective Bureau and began working for the District Attorney's office. On 26th July 1916, Fickert ordered the arrest of Mooney, his wife Rena Mooney, Warren Billings, Israel Weinberg and Edward Nolan. Mooney and his wife were on vacation at Montesano at the time. When Mooney read in the San Francisco Examiner that he was wanted by the police he immediately returned to San Francisco and gave himself up. The newspapers incorrectly reported that Mooney had "fled the city" and failed to mention that he had purchased return tickets when he left San Francisco.

None of the witnesses of the bombing identified the defendants in the lineup. The prosecution case was instead based on the testimony of two men, an unemployed waiter, John McDonald and Frank Oxman, a cattleman from Oregon. They claimed that they saw Warren Billings plant the bomb at 1.50 p.m. Oxman saw Mooney and his wife talking with Billings a few minutes later. However, at the trial, a photograph showed that the couple were over a mile from the scene. A clock in the photograph clearly read 1.58 p.m. The heavy traffic at the time meant that it was impossible for Mooney and his wife to have been at the scene of the bombing at 1.50 p.m. Despite this, Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life-imprisonment. Rena Mooney and Israel Weinberg were found not guilty and Edward Nolan was never brought to trial.

A large number of people believed that Billings and Mooney had been framed. Those involved in the campaign to get them released included Robert Minor, Fremont Older, George Bernard Shaw, Heywood Broun, Samuel Gompers, Eugene V. Debs, Roger Baldwin, John Dewey, John Haynes Holmes, Oswald Garrison Villard, Norman Hapgood, Crystal Eastman, Norman Thomas, Upton Sinclair, Theodore Dreiser, Sinclair Lewis, Lincoln Steffens, H. L. Mencken, Burton K. Wheeler, Sherwood Anderson, Abraham Muste, Harry Bridges, James Larkin, James Cannon, William Z. Foster, Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman, John Bright, William Haywood, William A. White, Carl Sandburg, Arturo Giovannitti and Robert Lovett.

Mooney's defence team complained about the method of selecting his jury. Bourke Cockran pointed out that in San Francisco "each Superior Court Judge places in the box from which the trial jurors are drawn the names of such persons as he may think proper. In theory he is supposed to choose persons peculiarly well qualified to decide issues of fact. In actual practice he places in the box the names of men who ask to be selected. The practical result is that a jury panel is a collection of the lame, the halt, the blind, and the incapable, with a few exceptions, and these are well known to the District Attorney who is thus enabled to pick a jury of his own choice." It was also discovered that William MacNevin, the foreman of Mooney's jury, was a close friend of Edward Cunha, who led the prosecution. MacNevin's wife later claimed her husband was in collusion with Cunha during the trial.

The American government also became concerned about the Mooney and Billings Case and the Secretary of Labor, William Bauchop Wilson, delegated John Densmore, the Director of General Employment, to investigate the case. By secretly installing a dictaphone in the private office of the District Attorney he was able to discover that Mooney and Billings had probably been framed by Charles Fickert. The report was leaked to Fremont Older who published it in the San Francisco Call on 23rd November 1917.

There were protests all over the world and President Woodrow Wilson called on William Stephens, the Governor of California, to look again at the case. Two weeks before Mooney was scheduled to hang, Stephens commuted his sentence to life imprisonment in San Quentin. Soon afterwards Mooney wrote to Stephens: "I prefer a glorious death at the hands of my traducers, you included, to a living grave."

In November 1920, Draper Hand of the San Francisco Police Department, went to Mayor James Rolph and admitted that he had helped Charles Fickert and Martin Swanson to frame Mooney. Hand also confessed that he had arranged for John McDonald to get a job when he began threatening to tell the newspapers that he had lied in court about Mooney and Billings. Mooney's defence team now began to search for MacDonald. He was found in January 1921 and agreed to make a full confession. He claimed he did see two men with the large suitcase but was unable to get a good look at them. When he reported the incident to District Attorney Charles Fickert he was asked to say the men were identify Mooney and Warren Billings. Fickert said that if he did this "I will see that you get the biggest slice of the reward." Later two witnesses, Edgar Rigall and Earl K. Hatcher, came forward and provided evidence that Frank Oxman was 200 miles away during the bombing and could not have seen what he told the court at the trial of Mooney.

In February 1921 John McDonald confessed that the police had forced him to lie about the planting of the bomb. Despite this new evidence the Californian authorities refused a retrial. After the publication of this new evidence it was generally believed that Charles Fickert and Martin Swanson had framed Mooney and Billings. However, Republican governors over the next twenty years: William Stephens (1917-1923), Friend Richardson (1923-1927), Clement Young (1927-1931), James Rolph (1931-1934) and Frank Merriam (1934-39) all refused to order the release of the two men.The international campaign to free Mooney and Billings continued.

In a survey carried out in 1935 and it was discovered that Tom Mooney was one of the four best known Americans in Europe (other three were Franklin D. Roosevelt, Charles A. Lindbergh and Henry Ford).

In 1937 a group of politicians led by Caroline O'Day, Nan Honeyman, Jerry O'Connell, Emanuel Celler, James E. Murray, Vito Marcantonio, Gerald Nye and Usher Burdick asked President Franklin D. Roosevelt to intercede in the case. When Roosevelt declined Murray and O'Connell introduced a resolution in the Senate calling on Governor Frank Merriam to pardon Mooney and Billings.

In November 1938 Culbert Olson was elected as Governor of California. He was the first member of the Democratic Party to hold this office for forty-four years. Soon after gaining power Olson ordered that Mooney and Warren Billings should be released from prison. Rena Mooney, who welcomed her husband as he left San Quentin was quoted as saying: "These twenty-two long years have been moth-eaten. Life to me has been something like a cloak. There is little left but the tatters."

A crowd of 25,000 greeted Mooney in San Francisco. Over $20,000 in debt, Mooney planned a lecture tour on the merits of the New Deal, trade union rights and the dangers of fascism in Europe. However, he was a sick man and a month after being released from prison he had an emergency operation to remove his gallbladder. For the next two years he had three more operations and spent most of his time in hospital. Tom Mooney died on 6th March, 1942.

On the day in 1891 Mary Jane Stafford died. Stafford was born in Hyde Park, Vermont, on 31st December, 1834. When she was three years old Mary's family moved to Crete, Illinois. After leaving school she taught in Joliet, Shawneetown and Cairo.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War the Union Army arrived to protect Cairo from the Confederate Army. As the town was situated at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. A series of epidemic diseases broke out amongst the troops and Stafford volunteered her services as a nurse.

In the summer of 1861 Stafford began work with Mary Ann Bickerdyke at Fort Donelson. Stafford also served under General Ulysses S. Grant. at Shiloh in Tennessee. She also worked on the hospital ships, City of Memphis and Hazel Dell.

After the war Stafford was determined to become a doctor. She graduated from the Medical College for Women in New York in 1869. She also studied at the University of Breslaw in Germany, wher she performed the first ovariotomy ever done by a woman.

In 1872 Mary Jane Stafford opened a private practice in Chicago. Later she became professor of women's diseases at the Boston University School of Medicine and a staff doctor at the Massachusetts Homeopathic Hospital.

On the day in 1895 journalist George Augustus Sala died. Sala, the youngest son of Augustus Sala (1792-1828) and Henrietta Simon (1789-1860), was born on 24th November, 1828. After the death of his father, George's mother supported herself and five surviving children by teaching singing and giving annual concerts in London and Brighton.

Educated at the Pestalozzian school at Turnham Green, Sala left at fifteen to become a clerk. Later he found work drawing railway plans during the Railway Mania of 1845. A talented artist, Sala also worked as a scene-painter at the Lyceum Theatre and in 1848 was commissioned to illustrate Albert Smith's The Man in the Moon. This was followed by an illustrated guidebook for foreign tourists that was published by Rudolf Ackermann. Other work included prints of the Great Exhibition and the funeral of the Duke of Wellington.

Sala was also interesting in becoming a journalist and in 1851 Charles Dickens accepted his article, The Key of the Street, for his journal, Household Words. This was the first of many articles that Dickens published over the next few years. In April, 1856, Dickens sent Sala to Russia as the journal's special correspondent. Sala also contributed to the author's next venture, All the Year Round and other journals such as the London Illustrated News, Punch Magazine and Cornhill Magazine.

In 1857, Sala began writing for the Daily Telegraph. For the next twenty-five years he contributed an average of ten articles a week. Although paid £2,000 a year for his work, Sala, who was an avid collector of rare books and expensive china, was always in debt.

George Augustus Sala loved travelling and in 1863 accepted the offer of becoming the Telegraph's foreign correspondent. Over the next few years he reported on wars and uprisings all over the world. During the Franco-German War he was arrested in Paris as a spy but was eventually released from prison. He wrote several books based on his travels including From Waterloo to the Peninsula (1867), Rome and Venice (1869), Paris (1880), America Revisited (1882), A Journey Due South (1885) and Right Round the World (1888).

After leaving the Daily Telegraph Sala moved to Brighton where he attempted to start his own periodical, Sala's Journal. The venture failed and left him deeply in debt and he was forced to sell his large library of books.

On the day in 1926 Agatha Christie disappeared for ten days. Her car was found in a chalk pit in Newland's Corner, Surrey. She was eventually found staying at the Old Swan Hotel in Harrogate under the name of the woman with whom Archibald Christie had recently admitted to having an affair. She claimed to have suffered a nervous breakdown and a fugue state caused by the death of her mother and her husband's infidelity. The couple were divorced in 1928.

After recovering from her nervous breakdown Agatha Christie returned to writing novels. This included The Big Four (1927), The Mystery of the Blue Train (1928) and The Seven Dials Mystery (1929). Her next book, The Murder at the Vicarage (1930), was the first one to feature Miss Jane Marple.

In 1930, Agatha Christie married the archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan. The couple did a lot of travelling and this gave her plenty of material for her detective stories. In 1931 Christie published The Sittaford Mystery (1931). This was followed by Peril at End House (1932), Lord Edgware Dies (1933), Murder on the Orient Express (1934), Why Didn't They Ask Evans? (1934), Three Act Tragedy (1935), Death in the Clouds (1935), The A.B.C. Murders (1936), Murder in Mesopotamia (1936), Cards on the Table (1936), Dumb Witness (1937), Death on the Nile (1937), Appointment with Death (1938), Hercule Poirot's Christmas (1938), Murder is Easy (1939) and And Then There Were None (1939).

The Second World War did not reduce Christie's productivity. During the war she published Sad Cypress (1940), One, Two, Buckle My Shoe (1940), Evil Under the Sun (1941), N or M? (1941), The Body in the Library (1942), Five Little Pigs (1942), The Moving Finger (1942), Towards Zero (1944), Death Comes as the End (1945) and Sparkling Cyanide (1945).

After the war Christie continued to publish novels about the murder investigations of Hercule Poirot, Miss Marble, Colonel Race, Ariadne Oliver, Tommy Beresford and Tuppence Cowley. This included The Hollow (1946), Taken at the Flood (1948), Crooked House (1949), A Murder is Announced (1950), They Came to Baghdad (1951), Mrs McGinty's Dead (1952) and They Do It with Mirrors (1952).

Christie also wrote for the theatre. Her stage play, The Mousetrap, opened at the Ambassadors Theatre in London on 25th November 1952. It is still running after more than 20,000 performances.

Other books by Christie include After the Funeral (1953), A Pocket Full of Rye (1953), Destination Unknown (1954), Hickory Dickory Dock (1955), Dead Man's Folly (1956), 4.50 from Paddington (1957), Ordeal by Innocence (1958), Cat Among the Pigeons (1959), The Pale Horse (1961), The Mirror Crack'd from Side to Side (1962), The Clocks (1963), A Caribbean Mystery (1964), At Bertram's Hotel (1965), Third Girl (1966), Endless Night (1967), By the Pricking of My Thumbs (1968), Hallowe'en Party (1969) and Passenger to Frankfurt (1970).

In 1971 Agatha Christie was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire. Her final books included Nemesis (1971), Elephants Can Remember (1972), Postern of Fate (1973), Curtain (1975) and Sleeping Murder (1976).

Agatha Christie died on 12th January 1976, at Winterbrook House. She is buried in the nearby St Mary's Churchyard in Cholsey. It has been estimated that four billion copies of her novels have been sold. UNESCO claims that she is currently the most translated individual author in the world.

On the day in 1949 Helen Archdale died at 17 Grove Court, St John's Wood. Helen Russel, the daughter of Alexander Russel and Helen De Lacy Evans, was born in 1876. Her father was the editor of The Scotsman, who had campaigned for the entry of Sophia Jex-Blake to the medical school in Edinburgh. Her mother was one of the students involved in that campaign.

Helen was educated at St Leonards School and University of St Andrews (1893-94). In 1901 Helen married Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Montgomery Archdale, who was stationed in India. Over the next few years she gave birth to two sons and a daughter.

On her return to England she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). On 9th October 1909 she took part in a WSPU demonstration in Edinburgh. Later that month Helen Archdale was arrested with Adela Pankhurst and Maud Joachim in Dundee after interrupting a meeting being held by the local MP, Winston Churchill. On 20th October all three women went on hunger strike. They were all released after four days of imprisonment.

In March 1910 she became WSPU organizer in Sheffield. The following year she moved to London to act as the WSPU prisoners' secretary. In December 1911 she was sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison for breaking a window in a government building. On her release Archdale worked on the WSPU newspaper, The Suffragette. During this period she left her husband, Theodore Montgomery Archdale.

During the First World War she started a training farm for women agricultural workers, served as a clerical worker with Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps from 1917, and in 1918 worked in the women's department of the Ministry of National Service.

After leaving her husband Helen Archdale began a relationship with Margaret Haig Thomas. According to her biographer, David Doughan: "Helen Archdale had an intense relationship with Lady Rhondda, which seems to have begun in committee work during the First World War, though they also shared a background in suffrage militancy. By the early 1920s, she was sharing an apartment, and, together with her family, a country house (Stonepits, Kent) with Lady Rhondda."

Lady Rhondda founded the political magazine Time and Tide in 1920. Helen Archdale became the first editor of the magazine. The following year the two women launched the Six Point Group of Great Britain, which focused on what she regarded as the six key issues for women: The six original specific aims were: (1) Satisfactory legislation on child assault; (2) Satisfactory legislation for the widowed mother; (3) Satisfactory legislation for the unmarried mother and her child; (4) Equal rights of guardianship for married parents; (5) Equal pay for teachers; (6) Equal opportunities for men and women in the civil service.

At first Time and Tide supported left-wing causes but over the years the magazine, like its owner, moved to the right. As David Doughan points out: "However, philosophical disagreements, as well as Lady Rhondda's increasing editorial interventions, resulted in her being effectively forced out of the editorship of Time and Tide in 1926. Although she remained a director of Time and Tide Publishing Company, after her resignation specifically feminist concerns were gradually marginalized in Time and Tide."

In 1927 Archdale she began work for the Women's International Organizations in Geneva. Archdale was also International Secretary of the Six Point Group of Great Britain and chairperson of Equal Rights International. She was also active in the International Federation of Business and Professional Women. She also contributed to The Times, The Daily News and The Scotsman.

On the day in 1972 Dorothy Hunt had a meeting with Michelle Clark, a journalist working for CBS. Dorothy was married to E. Howard Hunt, a senior figure in the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

On 3rd July, 1972, Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker and James W. McCord were arrested while removing electronic devices from the Democratic Party campaign offices in an apartment block called Watergate. The phone number of E. Howard Hunt was found in address books of two of the burglars. Reporters were able to link the break-in to the White House. Bob Woodward, a reporter working for the Washington Post was told by a friend who was employed by the government, that senior aides of President Richard Nixon, had paid the burglars to obtain information about its political opponents.

E. Howard Hunt threatened to reveal details of who paid him to organize the Watergate break-in. Dorothy Hunt took part in the negotiations with Charles Colson. According to investigator Sherman Skolnick, Hunt also had information on the assassination of John F. Kennedy. He argued that if "Nixon didn't pay heavy to suppress the documents they had showing he was implicated in the planning and carrying out, by the FBI and the CIA, of the political murder of President Kennedy"

James W. McCord claimed that Dorothy told him that at a meeting with her husband's attorney, William O. Buttmann, she revealed that Hunt had information that would "blow the White House out of the water". In October, 1972, Dorothy Hunt attempted to speak to Charles Colson. He refused to talk to her but later admitted to the New York Times that she was "upset at the interruption of payments from Nixon's associates to Watergate defendants."

On 15th November, Colson met with Richard Nixon, H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman at Camp David to discuss Howard Hunt's blackmail threat. John N. Mitchell was also getting worried by Dorothy Hunt's threats and he asked John Dean to use a secret White House fund to "get the Hunt situation settled down". Eventually it was arranged for Frederick LaRue to give Hunt about $250,000 to buy his silence.

However, on 8th December, 1972, Dorothy Hunt had a meeting with Michelle Clark, a journalist working for CBS. According to Sherman Skolnick, Clark was working on a story on the Watergate case: "Ms Clark had lots of insight into the bugging and cover-up through her boyfriend, a CIA operative." Also with Hunt and Clark was Chicago Congressman George Collins.

Dorothy Hunt, Michelle Clark and George Collins took the Flight 533 from Washington to Chicago. The aircraft hit the branches of trees close to Midway Airport: "It then hit the roofs of a number of neighborhood bungalows before plowing into the home of Mrs. Veronica Kuculich at 3722 70th Place, demolishing the home and killing her and a daughter, Theresa. The plane burst into flames killing a total of 45 persons, 43 of them on the plane, including the pilot and first and second officers. Eighteen passengers survived." Hunt, Clark and Collins were all killed in the accident.

Just before Dorothy Hunt boarded the aircraft she purchased $250,000 in flight insurance payable to E. Howard Hunt. In his book Undercover (1974) Hunt claims he was unaware that his wife planned to do this. In the book he also tried to explain what his wife was doing with $10,000 in her purse. According to Hunt it was money to be invested with Hal Carlstead in "two already-built Holiday Inns in the Chicago area".

The following month E. Howard Hunt pleaded guilty to burglary and wiretapping and eventually served 33 months in prison. Hunt kept his silence although another member of the Watergate team, James W. McCord, wrote a letter to Judge John J. Sirica claiming that the defendants had pleaded guilty under pressure (from John Dean and John N. Mitchell) and that perjury had been committed.

The airplane crash was blamed on equipment malfunctions. Carl Oglesby (The Yankee and Cowboy War) has pointed out that the day after the crash, White House aide Egil Krogh was appointed Undersecretary of Transportation, supervising the National Transportation Safety Board and the Federal Aviation Association - the two agencies charged with investigating the airline crash. A week later, Nixon's deputy assistant Alexander P. Butterfield was made the new head of the FAA.

Several writers, including Robert J. Groden, Peter Dale Scott, Alan J. Weberman, Sherman Skolnick and Carl Oglesby, have suggested that Dorothy Hunt was murdered. In 1974, Charles Colson, Howard Hunt's boss at the White House, told Time Magazine: "I think they killed Dorothy Hunt." (7/8/1974)

Barboura Morris also raised several issues in her article, Flight 553: The Watergate Murder? that appeared in Big Brother and the Holding Company: the world behind Watergate (1975) Morris claimed that Attorney General John N. Mitchell was under investigation for corruptly helping the El Paso Natural Gas Company against its main competitor, the Northern Natural Gas Company. Mitchell's decision to drop anti-trust charges was worth an estimated $300 million to El Paso. Ralph Blodgett and James W. Kreuger, two attorneys working for Northern Natural Gas Company in the investigation of Mitchell, were both killed in the crash. .

Morris also claimed that just hours after the crash an anonymous call was made to the WBBM Chicago (CBS) talk show. The caller described himself as a radio ham who had monitored ground control's communications with 553, and he reported an exchange concerning gross control tower error or sabotage. CBS, the employer of Michelle Clark, kept this information from the authorities investigating the accident. One FBI agent went straight to Midway's control tower and confiscated the tape containing information concerning the crash. The FBI did this before the NTSB could act - a unique and illegal intervention.

Morris also pointed out that FBI agents were at the scene of the crash before the Fire Department, which received a call within one minute of the crash. The FBI later claimed that 12 agents reached the scene of the crash. Later it was revealed that there were over 50 agents searching through the wreckage.

(It was completely irregular for the FBI to get involved in investigating a crash until invited in by the National Transportation Safety Board. The FBI director justified this action because it considered the accident to have been the result of sabotage. That raises two issues: (i) How were they able to get to the crash scene so quickly? (ii) Why did they believe Flight 553 had been a case of possible sabotage? Morris does not answer these questions. However, it could be argued that it is possible to answer both questions with the same answer. The FBI had been told that Flight 553 was going to crash as it landed in Chicago.

On the day in 1978 Golda Meir died in Jerusalem. Golda Mobovich, the daughter of Jewish parents, was born in Kiev, Russia in 1898. When she was a child her family emigrated to the United States. The family settled in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. After graduating from college she taught in a local school.

Golda married Morris Myerson in 1917 but later adopted the Hebrew name of Meir. The couple emigrated to Palestine in 1921 and became active in the emerging socialist movement in the country. She was elected to the woman's labour council of Histadrut in 1928.

The Jewish state of Israel was established on 14th May 1948 when the British mandate over Palestine came to an end. David Ben-Gurion became prime minister and appointed Golda Meir as Israeli ambassador to the Soviet Union (1948-49), Minister of Labour (1949-56) and Foreign Minister (1956-66).

Golda Meir became prime minister in 1969. In this post she clashed with Moshe Dayan, the Defence Minister, who wanted to colonize the Arab territories occupied during the Six-Day War. For a while Meir wanted to negotiate a peace settlement that would allow the return of Sinai to Egypt and the Golan Heights to Syria. However, she eventually sided with Dayan.

On 6th October 1973, Egyptian and Syrian forces launched a surprise attack on Israel. Two days later the Egyptian Army crossed the Suez Canal while Syrian troops entered the Golan Heights. Israeli troops counter-attacked on 8th October. They crossed the Suez Canal near Ismailia and advanced towards Cairo. The Israelis also recaptured the Golan Heights and moved towards the Syrian capital. The October War came to an end when the United Nations arranged a cease-fire on 24th October.

The Labour Party won the general election in December, 1973. However, Golda Meir could not get her cabinet to agree on policies and she resigned in April 1974.