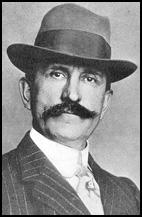

Fremont Older

Fremont Older was born in Appleton, Wisconsin, in 1856. He developed a desire to became a writer after reading the work of Charles Dickens. He moved to California in 1873 and two years later became managing director of the San Francisco Bulletin.

When he took over the newspaper it had a circulation of 9,000 and was losing $3,000 a month. Older used the newspaper to wage a campaign against political corruption. His biographer has pointed out: "Older's journalism was populist, and to be sure, sensational, but below the sensationalism lay a bedrock of uncompromising rectitude. Older's rectitude almost cost him his life on at least three occasions." Ella Winter described him as an "editor of the old type, independent and fearlessly outspoken."

One of Fremont Older's major campaigns was against Mayor Eugene Schmitz, who was under the control of Abraham Ruef. Eventually he got them both convicted of extortion. As a result Older was the target of a dynamite plot. He was also kidnapped on Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco by car, and put aboard a southbound train. Luckily, following a tip-off, he was rescued in Santa Barbara.

On 22nd July, 1916, employers in San Francisco organized a march through the streets in favour of an improvement in national defence. Critics of the march such as William Jennings Bryan, claimed that the Preparedness March was being organized by financiers and factory owners who would benefit from increased spending on munitions. During the march a bomb went off in Steuart Street killing six people (four more died later). Two witnesses described two dark-skinned men, probably Mexicans, carrying a heavy suitcase near to where the bomb exploded.

On the evening of the bombing Martin Swanson went to see the District Attorney, Charles Fickert. Swanson told Fickert that despite the claims that it was the work of Mexicans, he was convinced that Tom Mooney and Warren Billings were responsible for the explosion. The next day Swanson resigned from the Public Utilities Protective Bureau and began working for the District Attorney's office. On 26th July 1916, Fickert ordered the arrest of Mooney, his wife Rena Mooney, Warren Billings, Israel Weinberg and Edward Nolan. Mooney and his wife were on vacation at Montesano at the time. When Mooney read in the San Francisco Examiner that he was wanted by the police he immediately returned to San Francisco and gave himself up. The newspapers incorrectly reported that Mooney had "fled the city" and failed to mention that he had purchased return tickets when he left San Francisco.

None of the witnesses of the bombing identified the defendants in the lineup. The prosecution case was instead based on the testimony of two men, an unemployed waiter, John McDonald and Frank Oxman, a cattleman from Oregon. They claimed that they saw Warren Billings plant the bomb at 1.50 p.m. Oxman saw Tom Mooney and his wife talking with Billings a few minutes later. However, at the trial, a photograph showed that the couple were over a mile from the scene. A clock in the photograph clearly read 1.58 p.m. The heavy traffic at the time meant that it was impossible for Mooney and his wife to have been at the scene of the bombing. Despite this, Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life-imprisonment. Rena Mooney and Israel Weinberg were found not guilty and Edward Nolan was never brought to trial.

Fremont Older was convinced that Mooney and Billings had been framed. He published letters in his newspaper that showed that the chief prosecution witness was not in San Francisco when the bomb went off and that the prosecution's case was fabricated. The owner of the San Francisco Bulletin did not share these views and gave him an ultimatum to drop the case or be fired. When he heard what had happened, William Randolph Hearst, offered him the post of editor of the San Francisco Call.

Considered to be one of the most important investigative journalists during the muckraking era, Older later became disillusioned by the state of journalism. In 1926 he was asked what had happened to these radical journalists: "Some of them are in jail, some of them, with little hope left, are still on the job, but more of them have been inoculated by the money madness that has seized America."

Ella Winter, the new wife of his old friend, Lincoln Steffens, met Fremont Older for the first time in 1926. She wrote about it in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "An extremely tall, powerful man sitting at a wooden desk piled high with books rose as we came in. He had huge hands, a big head, a face carved into deep lines of character, and his voice was full of kindliness."

Fremont Older died of a heart attack on 3rd March, 1935.

© John Simkin, May 2013

Primary Sources

(1) William Randolph Hearst had used his newspapers to campaign for the conviction of Tom Mooney. However in 1918 he changed his mind about his guilt and stated in the New York American that Mooney should not be executed. Fremont Older responded to this decision in an article published in the San Francisco Bulletin (21st March, 1918)

The public tolerated the trial methods because the lies knowingly given currency by the Hearst papers had convinced it that Mooney and his fellow prisoners were guilty. When Hearst denounces those methods he denounces himself. When he asks clemency for Mooney he asks that a wrong be undone which could never have been done without his conscious aid.

There can be no excuse or evasion for Hearst. All that he or his New York editor knows now about the trial of Mooney he and his San Francisco editors knew a year ago. If it appears now that Mooney has been unjustly treated it appeared so then.

The only difference is that a year ago it took courage and a willingness to make sacrifices, to demand justice for Mooney and that now it is dangerous for a newspaper to stand out against that demand.

Fickert's ship is going down. And the rats are leaving it.

(2) Cora Miranda Baggerly Older, San Francisco Call-Bulletin (10th October 1955)

Fremont’s last crusade was to free Tom Mooney. He had been sentenced to death for alleged participation in bombing the Preparedness Day parade, but his sentence had been commuted by President Woodrow Wilson.

For several years Fremont devoted much energy to collecting evidence that Mooney was innocent. Sometimes Fremont was discouraged about Mooney’s unpleasant letters from prison, but he never showed them to me. “If I were imprisoned for a crime I hadn’t committed,” he said “I suppose I’d be bitter too.”