On this day on 20th October

On this day in 1632 Christopher Wren was born. On 2nd September, 1666, the Great Fire of London destroyed a large area of the city. Charles II had to appoint someone to take charge of rebuilding London. After much thought the king gave the job to his childhood friend, Christopher Wren. This included the task of building over fifty new churches in London. Wren was also commissioned to design and build St. Paul's Cathedral. St. Paul's took thirty-five years to build. The most dramatic aspect of St. Paul's was its great dome. It was the second largest dome ever built (the largest was St. Peter's Basilica in Rome). Both domes were based on the one in the Pantheon built by the ancient Romans. Wren was sixty-six years old when he finished St. Paul's. Other buildings designed by Wren included the Royal Exchange, College of Physicians, Chelsea Hospital, the Royal Naval College, Custom House and the Drury Lane Theatre. When Christopher Wren died in 1723 he became the first person to be buried in St. Paul's Cathedral.

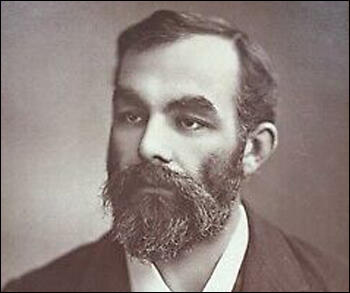

On this day in 1858 John Burns, English union leader and politician, was born. In 1879 Burns joined the Amalgamated Society of Engineers and found employment with the United Africa Company. Horrified by the way the Africans were treated, Burns became convinced that only socialism would remove the inequalities between races and classes. He returned to England in 1881 and soon afterwards formed the Battersea branch of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). One of the first people to join was another young engineer, Tom Mann.

When the London Dock Strike started in August 1889, Ben Tillett asked John Burns to help win the dispute. Burns, a passionate orator, helped to rally the dockers when they were considering the possibility of returning to work. He was also involved in raising money and gaining support from other trade unionists. During the dispute Burns emerged with Tillett and Tom Mann as one of the three main leaders of the strike.

The employers hoped to starve the dockers back to work but other trade union activists such as Will Thorne, Eleanor Marx, James Keir Hardie and Henry Hyde Champion, gave valuable support to the 10,000 men now out on strike. Organizations such as the Salvation Army and the Labour Church raised money for the strikers and their families. Trade Unions in Australia sent over £30,000 to help the dockers to continue the struggle. After five weeks the employers accepted defeat and granted all the dockers' main demands.

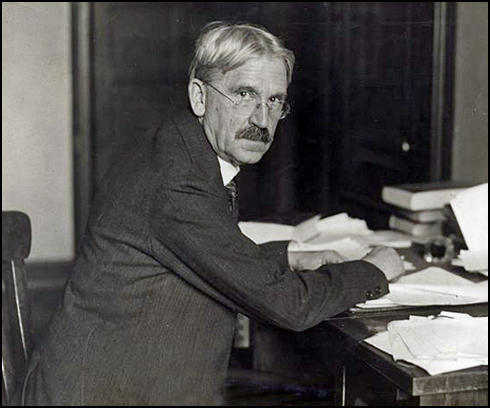

On this day in 1859, John Dewey, American psychologist and philosopher was born. In his books Dewey outlined his views on how education could improve society. The founder of what became known as the progressive education movement, Dewey argued that it was the job of education to encourage individuals to develop their full potential as human beings. He was especially critical of the rote learning of facts in schools and argued that children should learn by experience. In this way students would not just gain knowledge but would also develop skills, habits and attitudes necessary for them to solve a wide variety of problems. Dewey wrote several books on education and philosophy including Moral Principles in Education (1909), Interest and Effort in Education (1913) and Democracy and Education (1916).

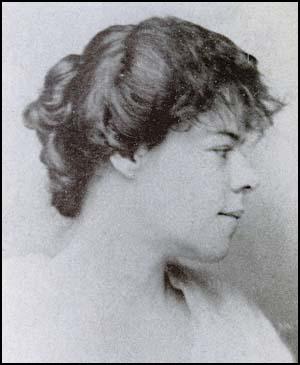

On this day in 1872 Flora Mayor, the youngest daughter of Reverand Joseph Bickersteth Mayor and Alexandrina Jessie, was born at Kingston Hill, Surrey. Flora was an identical twin. As Sybil Oldfield has pointed out: "Her relationship with Alice proved immensely positive for much of her life. Some twins... suffer from confusion about their identities or engage in acute sibling rivalry, but both Flora and Alice Mayor seem to have had strong, individual, characters from birth."

Flora was educated with Alice at Surbiton High School. According to one of the other students, they were "appallingly clever" and Flora went on to win the Sixth Form Latin Prize. However, her main pleasure came from acting in school productions and she had the star part in Little Lord Fauntleroy.

After leaving school Flora and Alice were sent to the Moravian School of Montmirail in Switzerland in order to perfect their French. Flora found the school very strictly regulated: "You can't do a single thing here without asking permission. You can't wear a different dress, you can't leave the room even without asking first - at least if you do somebody comes up with an awestruck face." Sybil Oldfield points out: "Both the twins, now eighteen years old, were frequently corrected for their pride, their untidiness, talking too much English, banging the door, bad sewing, and for sitting with their legs crossed. Many of the English girls began to have attacks of hysteria and fainting fits."

In 1892 Flora went to Newnham College to study history. She enjoyed her time at university but did not spend enough time studying. Flora wrote to Alice saying: "I don't get compliments about my history. I guess I'm going to do awfully badly." Flora took part in several theatre productions. Flora explained to Alice: "The Acting is simply lovely, infinitely nicer than our School for Scandal. Of course it's more fun to stage-manage and have the best part." Alice later remarked: "When Flora was at Newnham she burnt the candle at both ends and her health never recovered."

While at Cambridge University she met Mary Sheepshanks, who became a life-long friend. Flora introduced her to her sister Alice: "Mary Sheepshanks is an awfully nice girl to talk to". Alice agreed: "We had lots of interesting talk. I think (Mary Sheepshanks) about the most interesting girl I know to talk to ... she talks a good deal about men and matrimony, religion, books, art (very intelligently which is more than most people do)... She is certainly very keen on men and would get on with them admirably I'm sure... it is inspiring to the intellect to have her to discuss things with, we differ exceedingly."

Another friend was Florence Melian Stawell. In a letter to Alice she explained how they met: "Miss Stawell was very nice and just think in the evening she asked me to dance with her and afterwards to come and see her. Unenlightened as you are you don't know what an honour that is but she is absolutely the Queen of the College... I did feel proud. She dances most splendidly."

Flora Mayor and Mary Sheepshanks both became friends with Bertrand Russell, a strong advocate of free love and women's suffrage. Both women became critical of organised religion. Mary's sister, Dorothy Sheepshanks, recalled that, "Mary came to hold very advanced views in many respects, views of which father disapproved." John Sheepshanks, who was Bishop of Norwich at the time, was so shocked by Mary's views on politics and religion that he insisted that Mary must not spend any of her future university vacations at home.

Flora also had trouble from her father, Reverand Joseph Bickersteth Mayor. He wrote to her about the dangers of developing progressive political and religious views at Newnham College: "You will probably meet people of advanced views at Newnham, and some of our friends thought we were rash in letting you go there, but it is no longer possible for women to go through the world with their eyes shut, and if the highest education is reserved for those who have already a tendency to scepticism, or who belong to agnostic homes, it will be a very bad look-out for English society in the future.... Your position is probably better than that of most of your companions, both socially and intellectually, and in time you ought to be able to exercise some influence. That God's blessing may be with you through this eventful year is the earnest wish and prayer of your affectionate father."

While at university Flora, Florence Melian Stawell and Mary Sheepshanks began to teach adult literacy classes in the poor working-class district of Barnwell. Mary came to the conclusion that she wished to spend the rest of her life helping those from disadvantaged background. Flora was not so committed to social reform as Mary. Edward Marsh wrote to Bertrand Russell about meeting Mayor and Stawell in Cambridge. "I met a lovely person on Sunday. Miss Stawell, whom Dickinson was nice enough to ask me to meet. I think she's very superior indeed - she seems to have quite a rare feeling for beauty in art, I hope we shall see more of her. Mayor's sister was there too, she seemed rather common and flippant in comparison."

After leaving university Mary Sheepshanks found work at the Women's University Settlement, later the Blackfriars Settlement, in Southwark. Flora Mayor visited the settlement but admitted to her sister Alice that she could not do that kind of work: "I felt rather shy though I must say the Settlement people are very nice... I don't think I shall go again... The children are rather revolting I think on the whole."

According to her biographer, Merryn Williams: "A lively girl, she threw herself so fervently into Cambridge pleasures that despite earlier academic achievement at school, she got only a third. For the next seven years she thrashed about in search of an occupation."

Flora Mayor told Mary Sheepshanks that she intended to become an actress. This was influenced by seeing Ellen Terry perform. She told her Alice: "Ellen Terry is just sublime. Her gestures are so awfully natural, and her voice thrills me to the marrowbone." In another letter to Alice she wrote about her future career. "I am much exercised about my future ... I am wondering whether I really am capable of writing or not. I feel sometimes I'm not really in the least clever and that it is futile thinking of anything even like research work, let alone writing my prophesied book. Now my dear girl think the problem seriously over. It's awful when one's self-complacency gets undermined. If only I could go on the stage, it's the one thing I feel sure of... I don't know what to do if father is set against the Stage. I do want it and I feel more and more it's the thing I'm most fitted for but if it really grieves him I can't do it. I want awfully to talk to Mother and him about it."

In her book, Spinsters of this Parish (1984) Sybil Oldfield has argued: "Theatre life was insecure and even sordid; only actresses and prostitutes then ever used make-up and the unchaperoned young women would necessarily hear bad language backstage and be thrown into undesirable company.... Flora also had a host of opponents within her immediate family. Her mother was totally against the stage on snobbish grounds; her father was opposed on spiritual and moral grounds."

In February 1897 Flora Mayor joined a small theatre group based in Hastings. As Flora told her sister Alice: "The company arrived in detachments, very ordinary rather flashy-looking, shop-walking young men and pretty girls. The leading lady is charming-looking ... I feel horribly ugly beside them. There was one awful lady who crept along with a most terrible smile, very wicked-looking, a sort of Potiphar's wife. The ladies of the company hate her and she tells disgusting stories to the men. She was good-looking in a way but very musty... The dressing rooms are rather horrid gloomy little holes, no hot water or anything of that sort, a pot to act as a slop-pail... Conversation in the dressing room is not inspiring, it is mostly about what cleanser one uses and what lodgings one is going to take in the next town.... It really does seem to me rather immoral in places, and the tone is low throughout. As to the acting none of it was very bad and none very good... These stage experiences have been well worth getting - this is private of course."

When the season came to an end Flora was dismissed from the company. The actor, Arthur Paterson, told her that she had a "good figure, striking eyes but a ugly mouth". She wrote in her diary that "he thought my appearance was against me for seeing managers first off." However, Paterson thought she had an attractive personality and added: "You must make them talk to you and then you can do what you like with them."

Flora Mayor and Mary Sheepshanks remained good friends. Sybil Oldfield, the author of Spinsters of this Parish (1984) pointed out: "From time to time during her vain assaults on the agents and actor-managers in the capital, Flora vvould call in for tea and sympathy with her friend Mary Sheepshanks in her lodgings in Stepney. Mary could always be relied upon for approval and encouragement in the matter of striking out independently and unconventionally, so Flora did not have to be at all defensive about the stage with her, but she did wish she could have reported a little more success. However, Mary did not depress Flora by claiming to be any more successful in life than she was. Flora could even feel that she was cheering Mary up by recounting her own inglorious struggle... One bond between the two of them, in addition to their wish to achieve something in the world, was their shared sense that they were not a success with men. Men might find both women stimulating to talk to, but they did not invite them out. Marriage was far from being their great aim in life; nonetheless it was a sore point that neither of them could, at the age of twenty-five, feel confident of any man's passionate affection."

While out of work she began writing her first novel, Mrs Hammond's Children. During this period her brother, Henry Mayor, introduced her to Ernest Shepherd. Shepherd was an architect with a strong interest in literature, theatre, music and art. Flora introduced Shepherd to Mary Sheepshanks. As a result he volunteered to teach students at her Morley College for Working Men and Women. Shepherd was a great success at the college: "His enthusiasm for church architecture and for conducting student excursions to local landmarks - in fact for every kind of antiquity - was infectious."

On 23rd June, 1900, Flora, Mary, Ernest and Frank Earp went to Queensgate House together. Flora wrote in her diary: "Mary Sheepshanks came to lunch looking very pretty. We met Ernest and Frank Earp and went on the river, most successful and most cheerful tea. Ernest was very lively, possibly owing to Mary. Mary talked a good deal about Mr. Fountain's engagement."

Flora's novel was nearly completed when she was employed by the Benson Shakespearian Company at the Lyric Theatre, in December 1900. Flora received no pay for the first six weeks, then 15 shillings a week thereafter. Over the next few months she had small parts in The Taming of the Shrew and The Merchant of Venice. Flora was disturbed by the behaviour of some male members of the company. She wrote in her diary: "There is a great deal more pawing and squeezing from the managers than one is used to."

Ernest Shepherd came to see her in the plays. She wrote in her diary: "Ernest was so very nice. He is such a good friend, so awfully sympathetic. He said several times how lucky Benson was to have me." However, when the season came to an end, Flora was not retained. Flora Mayor returned to her novel writing. She showed the manuscript to Ernest, who encouraged her to send it to a publisher. It was rejected as not "being suitable neither for children nor for adults". Other publishers took a similar view but it was eventually accepted by a small firm called Johnson. Mrs Hammond's Children was brought out in September 1901 but it was ignored by the reviewers and sold very few copies.

Flora returned to the stage and got a small part in Our Boys, a comedy written by Henry James Byron. In 1902 she appeared in The Rivals by Richard Brinsley Sheridan. This was followed by Bethlehem, a play by Laurence Housman that was part of a production by the feminist, Edith Craig. In January 1903 she joined the cast of The Eternal City, a popular play written by Hall Caine, in its tour of the provinces.

Ernest Shepherd had fallen in love with Flora but he was not earning enough money as an architect to marry her. In March 1903, Ernest took a well-paying post as part of the Architectural Survey of India. He then proposed to Flora. At first she hesitated because she did not want to be separated from her family. She wrote to her twin sister, Alice: "I don't like the thought of India... what am I to do without you?" Flora also suspected that Ernest was really in love with Mary Sheepshanks. This he denied and eventually she agreed to marry him.

Under instructions from Flora, Shepherd went to see Mary. That night he wrote to Flora: "I called on Mary Sheepshanks today and told her about ourselves; you know I said I should... Of course I did not expect her to care one way or the other and I don't think she did; but she spoke very nicely, and was pleased that I had come to tell her; so though it was very awkward, embarrassing and hateful I am very glad I did it."

In April 1903, Ernest Shepherd left for India and Flora agreed to travel to the country to get married later that year. He wrote to Flora on 11th July complaining about his colleagues: "The men are unutterably dull - they never talk of anything but sport and bridge; and are intensely competitive about tennis... I don't know anybody - never shall know anybody as far as I can see; everyone is so exceedingly reserved." However, he did grow to love the country. On 2nd August he wrote: "I believe I am getting to like India - The lovely bright sun and clear air, the beautiful views of the country through the arches of the mosque quadrangle." In their letters they made arrangements to get married in Bombay.

In October, 1903, Ernest Shepherd was taken ill and he was sent to hospital in Simla. He wrote to Flora on 7th of that month: "Don't be alarmed at this address... When I went to see the Doctor on Monday he said I wasn't getting on a bit and looked the picture of misery - which I thought a gross libel - and therefore I'd better go into hospital and take vigorous measures to get well, which seemed sensible."

Ernest Shepherd died on 22nd October, 1903. He had been suffering not only from malaria but also from an undiagnosed acute enteric disorder. Flora later recalled that the telegram said: "Deeply regret Mr Shepherd died yesterday, funeral today." In her diary she wrote: "I read it over and over but it really didn't convey anything."

A few days later Flora received a letter from Fanny Fawcett, the woman who nursed him in Simla, enclosing a lock of Ernest's hair: "He (Ernest Shepherd) was conscious up to the last, but very, very weak of course. Just at the end I asked him if he had any message for you, and he said Tell her I have never forgotten her, and his last words were Best Beloved. I send you some of his hair which we cut off for you. He looked so peaceful and he was taken to his last resting-place surrounded by friends and exquisite flowers. Forgive a complete stranger saying so, but oh! his love for you was so true and ever-present with him, and I want you to feel this and to know his last thoughts were yours."

Mary Bateson wrote: "I heard from Alice Gardner today. I can't invent one single word or thought of consolation, and I can't pretend. Try not to mourn too terribly... Many of us stumble along without meeting the one co-soul; to have known that there was such an one, and what life could hold, can't have been a thing to crush and blight you utterly and for ever: I mean somehow or other you must live upon the riches you have got within you."

Flora kept a grief journal where she carried out a conversation with Ernest. The final entry was nine years later: "It is just ten years ago since our engagement. I am forty. You seem so young, thirty-one. I always love best your letter to Alice and the one about Alice to me. Help me if you can to cure my faults and make me more tender, you are so much much more unselfish. Each year brings us nearer."

In April 1904, Flora's brother, Henry Mayor, who had been appointed classics master at Clifton College, suggested that they should set up house together in Bristol. She agreed and returned to writing. However, she suffered from chronic bronchial asthma, that had been aggravated by the emotional shock of Ernest's death.

Flora Mayor was a member of the National Union of Suffrage Societies. However, she rejected the militant tactics of the Women Social & Political Union. In a letter to Alice in 1907 she explained how Annie Kenney had tried to persuade her to join the WSPU: "I saw the little Kenney again, to whom I feel quite warmhearted. She again implored me to join her, but I would have none of her, chiefly for your sake you stupid ass... I think it is rather cowardly of me when I do feel it is right and important."

In another letter in April 1908 Flora admitted she had been told by a friend, Emily Leaf, that Charlotte Despard and Anne Cobden Sanderson, "might take to bomb-throwing". She added that the women were "getting almost irresponsible through the strain of the one idea". However, she admitted that: "I feel just as keen on Suffrage. Why should one fool make any difference to me?"

Flora Mayor published her next novel, The Third Miss Symons, in 1913. Sybil Oldfield has argued that in the book: "'We watch an intensely loving child become an interesting, clever schoolgirl and then deteriorate, through loneliness and emotional disappointment, into a nagging, jealous, petty-minded caricature of the typical spinster, as she bullies the chambermaid or cheats at Patience or turns two hours of her company into a bad-tempered nightmare... Finally Henrietta even perceived an answer to why she had been unloved. It had been her own anger towards all the world which had exacerbated her awful loneliness - her resentment at being rejected had led to her rejecting everyone in her turn, and therefore she had been more rejected still."

The book received several good reviews. The Daily Telegraph commented that: "In many ways this slim volume represents an extremely interesting experiment. It ranks as fiction, and yet it is entirely unlike the average provender of the circulating libraries. It is very short... being something between a half and a third the length of an ordinary novel. It is also completely unpopular in style, making no concession to the common taste for gush and sentiment, eschewing decoration of every kind, and keeping close to the bare, austere presentation of a single character... It deserves success more than 90% of the novels which commend themselves so glibly to the public taste. For the author, Miss F.M. Mayor, is a true artist, restrained but confident in touch... her elaborate study of a spinster's life... is brilliantly clever, actual, and sincere. Without the slightest attempt to play upon the feelings, it reaches to the very heart of things, and leaves the reader with an aching sense of the intolerable waste of human nature."

After comparing Flora Mayor to Jane Austen and Elizabeth Gaskell the reviewer in the New Statesman added: "She uses English with a wise economy employed by few writers today; she moves the reader strongly again and again without ever resorting to hysterical methods; and she manages, above all, to interest one profoundly in the destinies of a wasted, unloved woman, whom in life nine-tenths of us would have passed by as boring or positively irritating. She enables us (unusual thing) to look at Henrietta from the outside and the inside at one and the same time."

On the outbreak of the First World War, some of Flora's friends such as Mary Sheepshanks and Bertrand Russell, were active in the anti-war movement. Sheepshanks was a leading figure in the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom whereas Russell was one of England's best known pacifists and became chairman of the Non-Conscription Fellowship. Flora was a strong supporter of the war and in her letters she referred scornfully to "the Bertrand Russell gang" and "the Lytton Strachey set" and suggested that they should be sent to the trenches on the Western Front.

After the First World War Mayor began work on her third novel, The Rector's Daughter. According to her biographer, Sybil Oldfield, the novel is about the 35 year old Mary Jocelyn: "Motherless from a child, isolated physically from her brothers, mentally from her subnormal sister, emotionally from her withdrawn and chilly father, and considered odd by all the contemporaries of her own social class." Merryn Williams has pointed out: "This is a longer and more complex novel, concentrating on the inner life of a middle-aged spinster, Mary Jocelyn, her unconsummated love for a married clergyman, and her lonely death."

The book had difficulty finding a publisher until Leonard Woolf and Virginia Woolf offered to take it on a commission basis for the Hogarth Press. The book was extremely popular with Britain's main literary figures. E. M. Forster wrote to Flora saying that: "Mary Jocelyn begins as ridiculous and ends as dignified: this seemed to me a very great achievement." John Masefield, the future Poet Laureate, also wrote to Flora: "It is a remarkable book and confirms you in your remarkable rank... It is a great advance in every way on your other two stories, though you know that I thought and still think both of them most unusually good in their own ways."

Gerald Gould wrote in The Saturday Review: "Miss Mayor has taken the subject-matter of all the serials in all the journals suitable for home reading of the last century, and made it live.... She has the true novelist's divine incommunicable gift: no shadows flit across her pages: she has but to mention someone, give him a phrase to say or even to write, and he puts on solidity and permanence."

Sylvia Lynd, was another reviewer who was very enthusiastic about The Rector's Daughter, in Time and Tide: "The Rector's Daughter belongs to the finest English tradition of novel writing. It is like a bitter Cranford. Miss Mayor explores depths of feeling that Mrs Gaskell's generation perhaps did not know and certainly did not admit to knowing. Mrs Mayor's genius struggles with exasperation where Mrs. Gaskell's struggled with the much milder demon of sentimentality... The Rector's daughter, Mary Jocelyn, is one of those sad figures of whom it is said that nothing has ever happened to them. Mrs Mayor reveals the meaninglessness of that phrase."

Despite the good reviews the book sold badly and it was soon out of print. Over the next few years Flora concentrated on writing ghost-stories. During this period Flora developed right-wing opinions that alienated her from her friends such as Mary Sheepshanks who was active in the Labour Party.

In September 1926, Flora Mayor had a letter published in the Church of England weekly newspaper, The Guardian, about the General Strike. She accused the miners' leaders of exploiting the "natural weaknesses of greed, intellectual laziness and moral cowardice". She contrasted the miners' refusal to work a longer shift with "the clergy, the house-masters at public schools and civil servants, all of whom (like her own father and brothers) were willing to work much longer than eight hours a day out of their sense of duty". The editor pointed out that "miners, unlike public schoolmasters, do not have three-and-a-half months' annual holiday, nor do they earn more money when they are sixty than when they are twenty, nor can they ever afford to retire before they are old."

Flora Mayor's next novel The Squire's Daughter appeared in 1929. The main character, Sir Geoffrey De Lacey, fortunes are in decline and at the end is forced to sell off his centuries-old ancestral home. The story deals with the problems that this causes his daughter. Unlike her previous novels, it was disliked by the critics. Gerald Gould, who had written such a good review of The Rector's Daughter, argued that he found the daughter's selfishness and emptiness unbearable. He added that "apparently she had some sort of charm and attractiveness which her creator never succeeds in communicating."

Flora Mayor died at her home at 7 East Heath Road, Hampstead, on 28th January 1932 of pneumonia complicated by influenza, and is buried in Hampstead cemetery. John Masefield wrote an obituary for The Times but such was the decline in her reputation that they refused to publish it.

On 28th February 1941, John O'London's Weekly, published a tribute to Flora Mayor by Rosamond Lehmann. In the article, Lehmann praises The Rector's Daughter with the comment that: "It is the daughter, Mary Jocelyn, who makes the book particularly memorable. She is my favourite character in contemporary fiction: favourite in that she is completely real to me, deeply moving, evoking as vivid and valid a sense of sympathy, pity, and admiration as do the Bronte sisters each time I live with them and through them again in the pages of Mrs. Gaskell's biography."

The Rector's Daughter was republished as a Penguin Modern Classic in 1973. This was followed in 1979 by The Third Miss Symons that appeared in the Virago Modern Classic series.

On this day in 1880 Lydia Maria Child died in Wayland, Massachusetts..

Lydia Maria Francis was born in Medford, Massachusetts on 11th February, 1802. In her twenties Child began to write popular historical novels such as Hobomok (1824) and The Rebels (1825). In 1826 established a periodical for children called Juvenile Miscellany. Her book, The Frugal Housewife (1829), was especially popular with the American public.

After hearing William Lloyd Garrison speak at a public meeting in 1831 Child began involved in the campaign against slavery. This included her book An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans (1833). This book converted people such as Charles Sumner to the cause but upset her traditional readers and sales of her other books dropped dramatically. She was eventually forced to cease publication of Juvenile Miscellany and instead she started with her husband, David Lee Child, a weekly newspaper, the Anti-Slavery Standard.

In 1839 Child and two other women, Lucretia Mott and Maria Weston Chapman were elected to the executive committee of the Anti-Slavery Society. This upset some members of the society were extremely upset by this decision. Lewis Tappan, the brother of Arthur Tappan, the president of the society, argued that: "To put a woman on the committee with men is contrary to the usages of civilized society."

Whereas one leaders, such as William Lloyd Garrison, Theodore Weld, Wendell Phillips and Frederick Douglass were as committed to women's rights as they were to the abolition of slavery. Others disagreed with this view and in 1840 a group including Arthur Tappan, James Birney and Gerrit Smith left the Anti-Slavery Society and formed a rival organization, the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society.

In 1861 Child controversially helped Harriet Jacobs publish Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. At the time the book was condemned because of the way it dealt with the sexual exploitation of young female slaves. Jacobs was also highly critical of the role of the Church in maintaining slavery.

Child also became concerned about the rights of women and Native Americans. This was reflected in the publication of History of the Condition of Woman in Various Ages and Nations and An Appeal for the Indians.

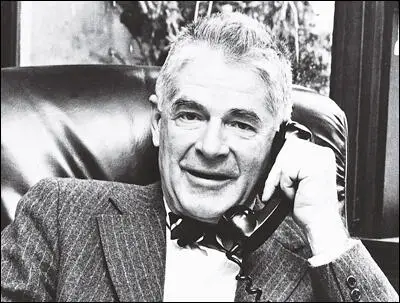

On this day in 1900 Wayne Morse, American politician was born. A member of the Republican Party, Morse was elected to the Senate in 1944. On the left of the party, Morse's liberal views made him a target of Joseph McCarthy. However, Mansfield was extremely popular in Oregon and he was able to survive McCarthy's claims that he was a Communist sympathizer. Although an anti-Communist, Morse continued to support the civil liberties of members of the Communist Party. He also signed the Declaration of Conscience, a document that attacked the abuses of McCarthyism. Morse was an advocate of Afro-American civil rights and fought for the desegregation of the District of Columbia and upset senators from the Deep South by inviting black leaders to meetings in the Senate. A strong opponent of the Vietnam War, Morse was one of only two senators to vote against the Gulf of Tonkin resolution in 1964. Morse was defeated for re-election in 1968. Wayne Morse died in Portland, Oregon, on 22nd July, 1974.

On this day in 1926 Eugene V. Debs died. Debs left school at the age of 14 and found work as a painter in a railroad yards. He became a railroad fireman in 1870 and soon afterwards became active in the trade union movement. Debs was elected national secretary of Brotherhood of Locomotive Fireman in 1880. In 1893 Debs was elected the first president of the American Railway Union (ARU). In 1894 George Pullman, the president of the Pullman Palace Car Company, decided to reduced the wages of his workers. When the company refused arbitration, the ARU called a strike. The attorney-general, Richard Olney, sought an injunction under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act against the Pullman Strike. As a result, of Olney's action, Debs was arrested and despite being defended by Clarence Darrow, was imprisoned. The case came before the Supreme Court in 1895. David Brewer spoke for the court on 27th May, explaining why he refused the American Railway Union's appeal. This decision was a great set-back for the trade union movement.

While serving his time in Woodstock Prison he read the works of Karl Marx. By the time he left prison in 1895 Debs became a socialist and believed that capitalism should be replaced by a new cooperative system. Although he advocated radical reform, Debs was opposed to the revolutionary violence supported by some left-wing political groups.

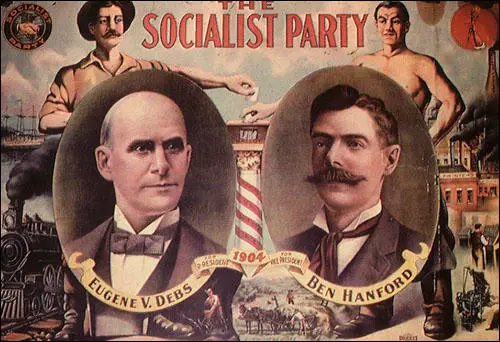

In the 1904 Presidential Election Eugene Debs was the Socialist Party of America candidate. His running-mate was Benjamin Hanford. Debs finished third to Theodore Roosevelt with 402,810 votes. This was an impressive performance and in the 1908 Presidential Election he managed to increase his vote to 420,793.

Between 1901 and 1912 membership of the Socialist Party of America grew from 13,000 to 118,000 and its journal Appeal to Reason was selling 500,000 copies a week. This provided a great platform for Debs and his running-mate, Emil Seidel, in the 1912 Presidential Election. During the campaign Debs explained why people should vote for him: "You must either vote for or against your own material interests as a wealth producer; there is no political purgatory in this nation of ours, despite the desperate efforts of so-called Progressive capitalists politicians to establish one. Socialism alone represents the material heaven of plenty for those who toil and the Socialist Party alone offers the political means for attaining that heaven of economic plenty which the toil of the workers of the world provides in unceasing and measureless flow. Capitalism represents the material hell of want and pinching poverty of degradation and prostitution for those who toil and in which you now exist, and each and every political party, other than the Socialist Party, stands for the perpetuation of the economic hell of capitalism. For the first time in all history you who toil possess the power to peacefully better your own condition. The little slip of paper which you hold in your hand on election day is more potent than all the armies of all the kings of earth."

Debs and Seidel won 901,551 votes (6.0%). This was the most impressive showing of any socialist candidate in the history of the United States. In some states the vote was much higher: Oklahoma (16.6), Nevada (16.5), Montana (13.6), Washington (12.9), California (12.2) and Idaho (11.5).

On this day in 1935 Arthur Henderson died. In 1908 he replaced Kier Hardie as leader of the Labour Party. In May 1915, Henderson became the first member of the Labour Party to hold a Cabinet post when Herbert Asquith invited him to join his coalition government. Henderson disagreed with those politicians who believed Germany should be harshly treated after the First World War, and as a result of the nationalist fervour of the 1918 General Election, he lost his seat. He returned at a by-election at Burnley in February 1924 and joined the government headed by Ramsay MacDonald as Home Secretary.

After the 1929 General Election victory, MacDonald appointed Henderson as his Foreign Secretary. In this post Henderson attempted to reduce political tensions in Europe. Diplomatic relations were re-established with the Soviet Union and Henderson gave his full support to the League of Nations by arguing for international arbitration, de-militarization and collective security. However, he resigned in 1931 when McDonald formed a National Government in order to cut public spending.

Henderson became leader of the Labour Party and ver the next few years Henderson worked tirelessly for world peace. Between 1932 and 1935 he chaired the Geneva Disarmament Conference and in 1934 his work was recognised when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

On this day in 1935 the Long March, undertaken by the armed forces of the Chinese Communist Party comes to an end. On 12th March 1925, Sun Yat-sen, the leader of the Kuomintang died. He was replaced by Chaing Kai-Shek who now carried out a purge that eliminated the communists from the organization. Those communists who survived managed to established the Jiangxi Soviet.

The nationalists now imposed a blockade and Mao Zedong decided to evacuate the area and establish a new stronghold in the north-west of China. In October 1934 Mao, Zhou Enlai, Lin Biao, Zhu De, and some 100,000 men and their dependents headed west through mountainous areas. The marchers experienced terrible hardships. The most notable passages included the crossing of the suspension bridge over a deep gorge at Luting (May, 1935), travelling over the Tahsueh Shan mountains (August, 1935) and the swampland of Sikang (September, 1935). The marchers covered about fifty miles a day and reached Shensi on 20th October 1935. Only around 30,000 survived the 8,000-mile march.

On this day in 1947 the House Un-American Activities Committee begins its investigation into Communist infiltration of the Hollywood film industry. Victor Navasky, the author of Naming Names (1982) has been pointed out that ten of the nineteen originally named members of the American Communist Party were Jews (Gordon Kahn, Lewis Milestone, Richard Collins, Albert Maltz, Robert Rossen, Samuel Ornitz, John Howard Lawson, Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole) and two others had been involved in the recent film, Crossfire (1947), that was an attack on anti-Semitism (Adrian Scott and Edward Dmytryk).

On this day in 1960 Christabel Marshall, women's suffrage and peace campaigner, died in Tenterden after suffering pneumonia and heart disease.

Christabel Gertrude Marshall, the youngest of the nine children of Emma Marshall (1828–1899), novelist, and Hugh Graham Marshall (c.1825–1899), manager of the West of England Bank, was born on 24 October 1871 at 38 High Street, Exeter.

Marshall was educated from 1894 at Somerville College, before moving to London where she worked as temporary secretary to Winston Churchill. After her conversion to Roman Catholicism she sometimes used the name, Christopher Marie St John, for her artistic work.

After a relationship with the musician Violet Gwynne in 1895, Marshall met Edith Craig, the daughter of Ellen Terry. From 1899, the two women shared a flat at 7 Smith Square, London. Their relationship became temporarily strained when Craig received a marriage proposal from the musician Martin Shaw and Marshall attempted suicide. Soon after this she accepted her lesbianism and took the name "Christopher St John".

Marshall's first published book, The Crimson Weed (1900), was a novel concerning the illegitimate son of an opera singer. She also acted in Gilbert Murray's translation of Andromache at the Garrick Theatre in 1904. Edith Craig arranged for her to appear in The Vikings at the Imperial Theatre. She also wrote a biography of Ellen Terry in 1907. Sybil Thorndike recalled Marshall as being "vivid … too much an individual in her life and work to be one of the most popular". Vita Sackville West added that "she was in the grand tradition of English eccentrics."

Marshall was active in the women's suffrage movement and joined the Women's Social and Political Union. She was also a committee member of the Catholic Women's Suffrage Society. In 1908 two members of the WSPU, Bessie Hatton and Cicely Hamilton formed the Women Writers Suffrage League. Marshall joined and later became a committee member of the organisation. Later that year the women formed the sister organisation, the Actresses' Franchise League. Marshall also joined this group that at this time included Elizabeth Robins, Kitty Marion, Winifred Mayo, Sime Seruya, Inez Bensusan, Ellen Terry, Lillah McCarthy, Sybil Thorndike, Lena Ashwell, Lily Langtry and Nina Boucicault.

The first meeting of the Actresses' Franchise League took place at the Criterion Restaurant at Piccadilly Circus. The AFL was open to anyone involved in the theatrical profession and its aim was to work for women's enfranchisement by educational methods, selling suffrage literature and staging propaganda plays. The AFL neither supported nor condemned militancy.

Inez Bensusan oversaw the writing, collection and publication of AFL plays. Pro-suffragette plays written by members of the Women Writers Suffrage League and performed by the AFL included the play How the Vote was Won a play co-written by Marshall and Cicely Hamilton. Another popular play was Votes for Women by Elizabeth Robins. Marshall appeared in another play by Hamilton, A Pageant of Great Women, that was directed by Edith Craig.

Christabel Marshall was arrested in 1909 for setting fire to a pillar box. However Marshall and Craig, like many members of the WSPU, began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were having too much influence over the organisation. Eventually, Marshall, joined Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard as members of the Women's Freedom League (WFL).

In 1911 Edith Craig established the Pioneer Players. Under her leadership this society became internationally known for promoting women's work in the theatre. Marshall contributed as dramatist, translator, and actor and was also honorary secretary from 1915 to 1920, and a member of the advisory and casting committees.

During the First World War, Marshall continued to act and write plays. She wrote about her relationship with Craig in her journal, The Golden Book (1911), and in her anonymously published second novel, Hungerheart: the Story of a Soul (1915). In 1916 Clare Atwood moved into the flat at 31 Bedford Street, Covent Garden, that she shared with Christabel Marshall, forming a permanent ménage à trois. Her biographer, Katharine Cockin, has pointed out that Marshall wrote they "achieved independence within their intimate relationships... working respectively in the theatre, art, and literature, drew creative inspiration and support from each other."

After the death of Ellen Terry in 1928, Edith Craig converted the barn in the grounds of her mother's house in Smallhythe Place, Tenterden, into a theatre. Their home next door, The Priest's House, became an important cultural centre that was visited by Radclyffe Hall, Una Troubridge, Vita Sackville West and Virginia Woolf. In 1929 acted there in A Midsummer Night's Dream and subsequently in several other plays.

Using the name Christopher St John, she wrote a biography of Christine Murrell in 1935. Murrell, a member of the Women's Social and Political Union, eventually became a member of the Medical Council of Great Britain.

Edith Craig died of coronary thrombosis and chronic myocarditis on 27th March 1947. According to Katharine Cockin, the author of Edith Craig (1998), Christabel Marshall destroyed all her "papers (and presumably the memoirs)" after Craig's death. A second biography, published in 1958, was of Ethel Smyth, the lover of Emmeline Pankhurst.

Christabel Marshall (Christopher Marie St John) died in Tenterden on 20th October 1960 after suffering pneumonia and heart disease.

On this day in 1964 Herbert Hoover died. Hoover was elected as president in 1928. A position he held during the Wall Street Crash. Within a short time, 100,000 American companies were forced to close and consequently many workers became unemployed. As there was no national system of unemployment benefit, the purchasing power of the American people fell dramatically. This in turn led to even more unemployment. Yip Harburg pointed out that before the Wall Street Crash, the American citizen thought: "We were the prosperous nation, and nothing could stop us now.... There was a feeling of continuity. If you made it, it was there forever. Suddenly the big dream exploded. The impact was unbelievable."

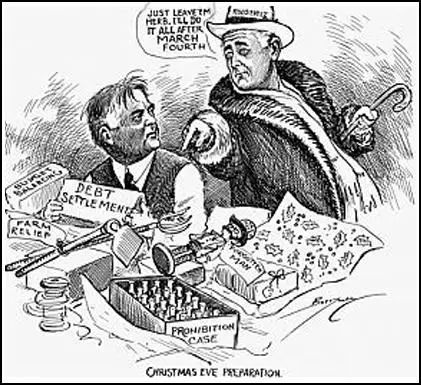

Franklin D. Roosevelt was selected as the Democratic Party candidate for the 1932 Presidential Election. There was a general agreement that Hoover ran a very bad campaign. Several leading Republican politicians, on the left of the party, including Robert LaFollette Jr of Wisconsin, Hiram Johnson of California, George Norris of Nebraska, Bronson Cutting of New Mexico and Smith Wildman Brookhart of Iowa, supported Roosevelt. Jonathan Bourne of Oregon stated: "I think Hoover is the most pitiful failure we have ever had in the White House."

The turnout, almost 40 million, was the largest in American history. Roosevelt received 22,825,016 votes to Hoover's 15,758,397. With a 472-59 margin in the Electoral College, he captured every state south and west of Pennsylvania. Roosevelt carried more counties than a presidential candidate had ever won before, including 282 that had never gone Democratic. Of the forty states in Hoover's victory coalition four years before, the President held but six. Hoover received 6 million fewer votes than he had in 1928. The Democrats gained ninety seats in the House of Representatives to give them a large majority (310-117) and won control of the Senate (60-36). Only one previous Republican candidate, William Howard Taft, had done as badly as Hoover.

all after March 4th." Cliff Berryman, Washington Evening Star (December, 1932)

On this day in 1973 President Richard Nixon fired U.S. Attorney General Elliot Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus after they refuse to remove special prosecutor Archibald Cox. Richardson had appointed Cox to investigate the alleged Watergate cover-up and illegal activity in the 1972 presidential campaign. Eventually, Robert Bork, the Solicitor-General, fired Cox.

An estimated 450,000 telegrams went sent to Richard Nixon protesting against his decision to remove Cox. The heads of 17 law colleges now called for Nixon's impeachment. Nixon was unable to resist the pressure and on 23rd October he agreed to comply with the subpoena and began releasing some of the tapes. The following month a gap of over 18 minutes was discovered on the tape of the conversation between Nixon and H. R. Haldeman on June 20, 1972. Nixon's secretary, Rose Mary Woods, denied deliberately erasing the tape. It was now clear that Nixon had been involved in the cover-up and members of the Senate began to call for his impeachment. On 9th August, 1974, Nixon became the first President of the United States to resign from office.