On this day on 17th August

On this day in 1510 Edmund Dudley was beheaded at Tower Hill.

Edmund Dudley, the eldest son of John Dudley and Elizabeth Bramshott Dudley was born in about 1462. His father, a Sussex gentleman and justice of the peace, was the second son of John Sutton, first Baron Dudley, and brother of William Dudley, bishop of Durham.

Dudley was educated at Oxford University. He then entered Gray's Inn one of the four ancient Inns of Court in London. This was the normal route for someone interested in a career in politics: "These were sometimes collectively referred to as the Third University of England, because in them young men were not only trained for the law but were also taught history... The legal education was particularly rigorous, consisting as it did in the study of case histories going back to Magna Carta, and excruciatingly complex disputations designed to test the vocational skills of students in preparing intricate writs and pleadings."

According to his biographer, S. J. Gunn: "There (Gray's Inn) he took a prominent part in the inn's learning exercises. In the later 1480s he gave the first known reading in any inn on quo warranto, the procedure by which the king challenged the exercise of private jurisdictions. Thus he demonstrated the interest in the king's rights which was to be a hallmark of his career."

Edmund Dudley was elected to Parliament in 1491. In November 1496 he was chosen one of the two under-sheriffs of London, and in 1501 he served on a commission to investigate infringements of the king's feudal rights and prerogatives in Sussex. In January 1504, Henry VII appointed Dudley to serve as speaker of the House of Commons. By July 1506 he was president of the king's council, the first layman to hold the position. Over the next few years Edmund Dudley and Richard Empson became the king's most dominant members.

Jasper Ridley has pointed out that Dudley and Empson were the chief instruments of the king's financial policy: "They seem to have been almost universally hated throughout England. They were accused of acting illegally when they extorted large sums of money from wealthy landowners under the recognisance system, and of not only obtaining this money for the King, but of enriching themselves in the process." Christopher Morris, the author of The Tudors (1955) has suggested that Dudley was the king's most "unpopular and unscrupulous minister".

Dudley's main role was raising money for the king. "His accounts, surviving with various degrees of completeness in at least four early seventeenth-century transcripts, run from 9 September 1504 to May 1508. They suggest his role was to manage the king's use of a miscellaneous range of opportunities for financial exploitation of his greater subjects. He sold offices, wardships, and licences to marry the widows of tenants-in-chief; pardons for treason, sedition, murder, riot, retaining, and other offences. In less than four years he collected some £219,316 6s. 11d. in cash and bonds for future payment. He also enforced the king's rights and capitalized on his resources in a more specialized way as chief justice of the royal forests south of the Trent."

Dudley was accused of using his position to build up his own wealth. By 1509 he had built up a landed estate in sixteen counties, worth some £550 a year gross, plus £5,000 or more in goods. He was granted a dozen stewardships of crown estates. Most of his money came from bribes concerning legal matters. Dudley and Empson were "resented and distrusted by the bishops and the older nobility". In recent years, historians have discovered a little more about the activities of Dudley and Empson. "Some of this new material seems to vindicate them to some extent, or at least to show that everything they did was justified by the law of England. Other documents confirm their high-handed methods."

Henry VII died on 21st April 1509, but the fact was not announced until the evening of the 23rd. The following day Dudley and Empson were arrested and sent to the Tower of London. It was claimed that after the death of Henry that he conspired to stage a coup d'état. As Roger Lockyer has argued: "Empson and Dudley were tried on a trumped-up charge of treason... Lack of gratitude was to be one of the most typical of Henry's characteristics." The main intention of Henry VIII was to suggest the "disavowal and reversal of the oppressive policies with which they were identified". The new king also declared an amnesty towards certain fines imposed on the aristocracy.

On this day in 1887 Marcus Garvey was born in St. Ann's Bay, Jamaica. After seven years of schooling he worked as a printer. He became an active trade unionist and in 1907 was elected vice president of compositors' branch of the printers' union. He helped lead a printer's strike (1908-09) and after it collapsed the union disintegrated.

In 1911 Garvey moved to England and briefly studied at Birbeck College where he met other blacks who were involved in the struggle to obtain independence from the British Empire. Inspired by what he heard he returned to Jamaica and established the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and published the pamphlet, The Negro Race and Its Problems. Garvey was influenced by the ideas of Booker T. Washington and made plans to develop a trade school for the poor similar to the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

Garvey arrived in the United States on 23rd March 1916 and immediately launched a year-long tour of the country. He organized the first branch of UNIA in June 1917 and began published the Negro World, a journal that promoted his African nationalist ideas. Garvey's organization was extremely popular and by 1919 UNIA had 30 branches and over 2 million members.

Like the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) Garvey campaigned against lynching, Jim Crow laws, denial of black voting rights and racial discrimination. Where UNIA differed from other civil rights organizations was on how the problem could be solved. Garvey doubted whether whites in the United States would ever agree to African Americans being treated as equals and argued for segregation rather than integration. Garvey suggested that African Americans should go and live in Africa. He wrote that he believed "in the principle of Europe for the Europeans, and Asia for the Asiatics" and "Africa for the Africans at home and abroad".

Garvey began to sign up recruits who were willing to travel to Africa and "clear out the white invaders". He formed an army, equipping them with uniforms and weapons. Garvey appealed to the new militant feelings of black that followed the end of the First World War and asked those African Americans who had been willing to fight for democracy in Europe to now join his army to fight for equal rights.

In 1919 Garvey formed the Black Cross Navigation and Trading Company. With $10,000,000 invested by his supporters Garvey purchased two steamships, Shadyside and Kanawha, to take African Americans to Africa. At a UNIA conference in August, 1920, Garvey was elected provisional president of Africa. He also had talks with the Ku Klux Klan about his plans to repatriate African Americans and published the first volume of Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey.

After making a couple of journeys to Africa the Black Cross Navigation and Trading Company ran out of money. Garvey was a poor businessman and although he was probably honest himself, several people in his company had been involved in corruption. Garvey was arrested and charged with fraud and in 1925 was sentenced to five years imprisonment. He had served half of his sentence when President Calvin Coolidge commuted the rest of his prison term and had him deported to Jamaica.

In 1928 Garvey went on a lecture tour of Britain, France, Belgium, Switzerland and Canada. On Garvey's return to Jamaica he established the People's Political Party and a new daily newspaper, The Blackman. The following year Garvey was defeated in the general election for a seat in Jamaica's colonial legislature.

In July, 1932, Marcus Garvey began publishing the evening newspaper, The New Jamaican. The venture was unsuccessful and the printing presses were seized for debts in 1933. He followed this with a monthly magazine, Black Man. He also launched an organization that he hoped would raise money to help create job opportunities for the rural poor in Jamaica.

The project was not a success and in March, 1935, Garvey moved to England where he published The Tragedy of White Injustice. Marcus Garvey continued to hold UNIA conventions and to tour the world making speeches on civil rights until his death in London on 10th June, 1940.

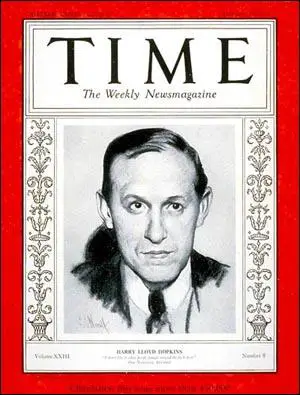

On this day in 1890 Harry Hopkins was born in Sioux City, Iowa.. After graduating from Grinnell College in 1912 he became a social worker in New York City. He was also active in the Democratic Party and a strong supporter of Alfred Smith.

In 1931 Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Hopkins as the executive director of the New York State Temporary Emergency Relief Administration. The historian, William E. Leuchtenburg, has argued: "Harry Hopkins... directed relief operations under Roosevelt in Albany. For a social worker, he was an odd sort. He belonged to no church, had been divorced and analyzed, liked race horses and women, was given to profanity and wisecracking, and had little patience with moralists... A small-town Iowan, he had the sallow complexion of a boy who had been reared in a big-city pool hall... He talked to reporters - often out of the side of his mouth - through thick curls of cigarette smoke, his tall, lean body sprawled over his chair, his face wry and twisted, his eyes darting and suspicious, his manner brusque, iconclastic, almost deliberately rude and outspoken."

When Roosevelt became president he recruited Hopkins to implement his various social welfare programs. As John C. Lee has pointed out: "On the whole, it is apparent that the mission of the Civil Works Administrator had been accomplished by 15th February 1934. His program had put over four million persons to work, thereby directly benefiting probably twelve million people otherwise dependent upon direct relief. The program put some seven hundred million dollars into general circulation. Such losses as occurred were negligible, on a percentage basis, and even those losses were probably added to the purchasing power of the country."

Frances Perkins later recalled: "Hopkins became not only Roosevelt's relief administrator but his general assistant as no one had been able to be. There was a temperamental sympathy between the men which made their relationship extremely easy as well as faithful and productive. Roosevelt was greatly enriched by Hopkins knowledge, ability, and humane attitude toward all facets of life."

The artist, Peggy Bacon met Hopkins during this period: "Pale urban-American type, emanating an aura of chilly cynicism and defeatest irony like a moony, melanchology newsboy selling papers on a cold night." Robert Sherwood, one of President Roosevelt's closest advisors, described him as "a profoundly shrewd and faintly ominous man."

The journalist, Raymond Gram Swing, became a close friend and argued in his book, Good Evening (1964): "One of my friendliest sources in the government was Harry Hopkins, who never was too busy to answer the telephone or see me in an emergency.... The public distrusted him for being a professional social worker who suddenly came to execute high government policy under the New Deal. That the policies he helped create turned out to be beneficial and preserved the American way of life, free enterprise included, will in time be recognized."

Hopkins worked for the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (1933-35) and the Works Projects Administration (1935-38). In a speech in 1936 Hopkins argued: "I believe the days of letting people live in misery, of being rock-bottom destitute, of children being hungry, of moralizing about rugged individualism in the light of modern facts - I believe those days are over in America. They have gone, and we are going forward in full belief that our economic system does not have to force people to live in miserable squalor in dirty houses, half fed, half clothed, and lacking decent medical care." As head of the WPA Hopkins employed more than 3 million people and was responsible for the building of highways, bridges, public buildings and parks.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized Hopkins to set up the Civil Works Administration (CWA). William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), has pointed out: "CWA was a federal operation from top to bottom; CWA workers were on the federal payroll. The agency took half its workers from relief rolls; the other half were people who needed jobs, but who did not have to demonstrate their poverty by submitting to a means test. CWA did not give a relief stipend but paid minimum wages. Hopkins, called on to mobilize in one winter almost as many men as had served in the armed forces in World War I, had to invent jobs for four million men and women in thirty days and put them to work. By mid-January, at its height, the CWA employed 4,230,000 persons."

During the four months of its existence, the CWA built or improved some 500,000 miles of roads, 40,000 schools, over 3,500 playgrounds and athletic fields, and 1,000 airports. The CWA employed 50,000 teachers to keep rural schools open and to teach adult education classes in the cities. The CWA also hired 3,000 artists and writers. It has been estimated that the CWA put a billion dollars of purchasing power into the sagging economy.

Roosevelt became concerned about creating a permanent class of people on relief work. He told Hopkins: "We must be careful it does not become a habit with the country... We must not take the position that we are going to have permanent depression in this country, and it is very important that we have somebody to say that quite forcefully to these people." Despite the protest of political figures such as Robert LaFollette and Bronson Cutting, the program came to an end in March, 1934.

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration now took up the relief burden again. It continued the CWA's unfinished work projects. FERA also erected five thousand public buildings and seven thousand bridges, cleared streams, dredged rivers and terraced land. FERA also employed teachers and over 1,500,000 adults were taught to read and write. It also ran nursery schools for children from low-income families, and helped 100,000 students to attend college.

By 1935 a total of $3,000,000,000 was distributed. Most of this money went to Home Relief Bureaus and Departments of Welfare for Poor Relief. Franklin D. Roosevelt felt he had little to show for this money. The Great Depression continued and over 20 million men were still receiving public assistance. He wrote to Edward House in November, 1934: "What I am seeking is the abolition of relief altogether. I cannot say so out loud yet but I hope to be able to substitute work for relief."

In January, 1935, Roosevelt proposed a gigantic program of emergency public employment, which would give work to 3,500,000 people without work. Roosevelt told Congress that relief was "a narcotic, a subtle destroyer of the human spirit... I am not willing that the vitality of our people be further sapped by the giving of cash, a market baskets, of a few hours of weekly work cutting grass, raking leaves or picking up papers in the public parks. The Federal Government must and shall quit this business of relief."

The Works Projects Administration (WPA) was established in April 1935. Harold Ickes wanted to head the agency. He argued that Harry Hopkins was an irresponsible spender and was not "priming the pump" but "just turning on the fire-plug". Ickes wanted the money spent on heavy capital expenditures whereas Hopkins advocated putting to work as many men as he could who were presently on relief. Roosevelt's main objective was to reduce the numbers on relief and he gave Hopkins overall control of the WPA.

In 1935 the WPA spent $4.9 billion (about 6.7 percent of GDP). The main objective was to provide one paid job for all families in which the breadwinner suffered long-term unemployment.Over the next few years the WPA built more than 2,500 hospitals, 5,900 school buildings, 1,000 airport landing fields, and nearly 13,000 playgrounds. At its peak in 1938, it provided paid jobs for three million unemployed men (and some women).

Hopkins also worked as Secretary of Commerce (1938-40). During the early stages of the Second World War he was Roosevelt's personal envoy to Britain. He was also a member of the War Production Board and served as Roosevelt's special assistant (1942-45). William Leahy worked closely with Hopkins: "Hopkins had an excellent mind. His manner of approach was direct and nobody could fool him, not even Churchill. He was never influenced by a person's rank. Roosevelt trusted him implicitly and Hopkins never betrayed that trust. The range of his activities covered all manner of civilian affairs - politics, war production, diplomatic matters - and, on many occasions, military affairs.... By his brilliant mind, his loyalty, and his selfless devotion to Franklin Roosevelt in helping carry on the war, Harry Hopkins soon erased completely any previous misgivings I might have held."

Raymond Gram Swing has pointed out: "It was his position as President Roosevelt's chief assistant in World War II that, in particular, needs to be better appreciated and valued. He was not Mr. Roosevelt's closest friend, for the President of the United States does not have friends in the true sense of the word. He cannot have loyalty to individuals, since he has placed his loyalty to the country first. And to be his first assistant calls for humility as well as devotion, and an ability almost on a par with his leader's. In the innumerable conferences Harry Hopkins attended abroad as the President's emissary, he was blunt of speech, adroit of mind, and dedicated to the requirements of victory."

Harry Hopkins became involved in controversy while at the Yalta Conference. The journalist, Drew Pearson, claimed that it was agreed that the Red Army should be the first military force to enter Berlin. Hopkins issued a statement on 23rd April, 1945: "There was no agreement made at Yalta whatever that the Russians should enter Berlin first. Indeed, there was no discussion of that whatever. The Chiefs of Staff had agreed with the Russian Chiefs of Staff and Stalin on the general strategy which was that both of us were going to push as hard as we could. It is equally untrue that General Bradley paused on the Elbe River at the request of the Russians so that the Russians could break through to Berlin first."

On the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt Hopkins helped arrange the Potsdam Conference for Harry S. Truman but retired from public life soon afterwards. Hopkins told his friend, Robert E. Sherwood: "You and I have got something great that we can take with us all the rest of our lives. It's a great realization. Because we know it's true what so many people believed about him and what made them love him. The President never let them down. That's what you and I can remember. Oh, we all know he could be exasperating, and he could seem to be temporizing and delaying, and he'd get us all worked tip when we thought he was making too many concessions to expediency. But all of that was in the little things, the unimportant things - and he knew exactly how the little and how unimportant they really were. But in the big things - all of the things that were of real, permanent importance - he never let the people down."

Harry Lloyd Hopkins died of cancer in New York City on 29th January, 1946.

On this day in 1913 Mark Felt was born in Twin Falls, Idaho. After graduating from the University of Idaho in 1935 he worked for James Pope, the Democratic senator for Idaho. Pope lost his seat after discovering details of corruption concerning arms dealings during the First World War.

Felt studied at the George Washington University Law School at night and joined the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1942. He worked at FBI headquarters for several years. He was also stationed at a number of field offices before being appointed head of FBI's Inspection Division in 1964.

By the early 1970s Felt was third in the FBI hierarchy after J. Edgar Hoover and William Sullivan. When Hoover died in May 1972, Felt expected to become the new director of the FBI (Sullivan had left the FBI in 1971). However, Richard Nixon decided to appoint an old friend, L. Patrick Gray, to the post.

Charles Nuzum was placed in charge of the FBI investigation into Watergate. However, as associate director, it was Felt's responsibility to compile all the information that came from from all FBI agents before it was sent to L. Patrick Gray.

On 19th October, 1972, White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman told Nixon a secret source had identified Felt as someone who was leaking information about Watergate to the press. Nixon considered sacking Felt but Haldeman urged caution: "He knows everything that`s to be known in the FBI. He has access to absolutely everything... If we move on him, he'll go out and unload everything."

L. Patrick Gray was forced to resign on 27th April, 1973, after the disclosure that he destroyed papers from the White House safe of E. Howard Hunt, the former CIA agent who had organized the Watergate break-in. Felt now became deputy director under William Ruckelshaus. Felt left the FBI in June 1973.

During the Watergate Scandal some people speculated that Mark Felt was Deep Throat. "It was not I and it is not I," Felt told Washingtonian magazine in 1974. In a press conference in August 1976 Felt denied once again being Deep Throat. He added that he would admit it if it was true as he thought it would have been his moral duty to remove a corrupt politician from power. However, he said, it was not possible to take credit for something he did not do.

In 1979 Mark Felt published his autobiography, The FBI Pyramid: Inside the FBI. He once again denied he was Deep Throat: "I was supposed to be jealous of Gray for having received the appointment as Acting Director instead of myself. They felt that my high position in the FBI gave me access to all the Watergate information and that I was releasing it to Woodward and Bernstein in an effort to discredit Gray so that he would be removed and I would have another chance at the job. Then there were those frequent instances when I had been much less than cooperative in responding to requests from the White House which I felt were improper. I suppose the White House staff had me tagged as an insubordinate. It is true I would like to have been appointed FBI director... but I never leaked information to Woodward and Bernstein or anyone else!"

The FBI Pyramid: Inside the FBI was co-written with Ralph de Toledano. He told Felt that the book would sell more copies if he admitted to being Deep Throat. Toledano later claimed: "Felt swore to me that he was not Deep Throat, that he had never leaked information to the Woodward-Bernstein team or anyone else. The book was published and bombed."

In 1980 Mark Felt and Edward S. Miller were charged with conspiring to violate the constitutional rights of Americans by authorising illegal break-ins and wire taps of people connected to suspected domestic bombers. This related to the investigation of the terrorist group, the Weather Underground. Richard Nixon, who had encouraged the FBI to destroy the group that had planted bombs at the Capitol, the Pentagon, and the State Department, appeared as a defense witness during the trial.

Felt and Miller were convicted by a jury on November 6, 1980. Although the charge carried a maximum sentence of 10 years in prison, Felt was fined $5,000 (Miller was fined $3,500). President Ronald Reagan pardoned both on 15th April, 1981. The president said they had "acted on high principle to bring an end to the terrorism that was threatening our nation."

Several writers have suggested that Mark Felt was Deep Throat. This includes Ronald Kessler (The Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI), James Mann (Atlantic Monthly) and Jack Limpert (Washingtonian). The first person to provide any real evidence that Felt was Deep Throat was Chase Culeman-Beckman. The 17 year old exposed Felt in high-school history paper in 1999. He revealed how as a 8 year old he was told Deep Throat’s identity by Jacob Bernstein, the son of Carl Bernstein. Culeman-Beckman's history teacher was not impressed and did not even give the essay an 'A' grade.

The reason why Felt was rejected as a serious Deep Throat candidate concerns the information he was giving to Bob Woodward. Some of it did include evidence acquired from the FBI investigation. However, most of the important information that Deep Throat revealed came from the CIA and the White House. How did Felt get hold of this information?

For example, one of the most important pieces of information Deep Throat gave Woodward was that Nixon’s was tapping his conversations at the White House. Woodward leaked this information to a staff member of Sam Ervin Committee. He in turn told Sam Dash and as a result Alexander P. Butterfield was questioned about the tapes. Only a very small number of people knew about the existence of these tapes. If Felt knew about these tapes he had his own Deep Throat. If this is the case, it was possibly William C. Sullivan, his former colleague at the FBI who was working for the White House during this period.

Felt, who leaked information to Time Magazine about what became known as the “Kissinger taps”, later admitted that he got this information from Sullivan (one of the first things that Sullivan had done when he was appointed by Richard Nixon was to transfer the wiretap logs to the White House). Sullivan was playing a double-game. He provided information to Nixon about the CIA role in the assassination of John F. Kennedy. It was this information that Nixon tried to use to control Richard Helms. However, Sullivan, like Felt, was a pro-Kennedy Democrat.

On the 25th anniversary of Nixon's resignation in 1999, Felt told a reporter that it would be "terrible" if someone in his position had been Deep Throat. "This would completely undermine the reputation that you might have as a loyal employee of the FBI," he said. "It just wouldn't fit at all."

Felt retired to Santa Rosa, California. In 2001 Felt had a stroke that robbed him of his memory. Before this happened Felt had told his daughter Joan that he was Deep Throat. In May, 2005, Felt's lawyer, John O'Connor, went public with the news. Felt was quoted as saying: "I don’t think being Deep Throat was anything to be proud of. You should not leak information to anyone." However, he added: "If you know your government is engaging in illegal and/or immoral acts, then you have an obligation to speak out that overrides confidentiality agreements and secrecy laws. It's never wrong to inform on serious criminal acts no matter who is perpetrating them."

Felt's daughter admitted that she had persuaded her father to admit being Deep Throat in an attempt to clear the family debts. She admits that the family have gone public in an attempt to obtain money. Joan Felt told journalists: "My son Nick is in law school and he'll owe $100,000 by the time he graduates. I am still a single mom, still supporting them (her children) to one degree or another."

Shortly afterwards Bob Woodward confirmed that Felt had provided him with important information during the Watergate investigation. Ben Bradlee also said that Felt was Deep Throat. However, Carl Bernstein was quick to add that Felt was only one of several important sources.

Ralph de Toledano, the co-author of The FBI Pyramid: Inside the FBI, was furious that Felt had lied to him about the identity of Deep Throat. De Toledano opened a lawsuit against Felt. In August 2007, a DC judge ordered the lawsuit, continued by De Toledano's sons, into arbitration.

Mark Felt died from heart failure on 18th December, 2008, at a hospice care facility in Santa Rosa, California.

On this day in 1935 Charlotte Perkins Gilman, suffering from breast cancer, committed suicide. She left a note that said: "When all usefulness is over, when one is assured of unavoidable and imminent death, it is the simplest of human rights to choose a quick and easy death in place of a slow and horrible one. I have preferred chloroform to cancer."

Charlotte Perkins was born in Hartford, Connecticut, on 3rd July, 1860. Her father, Frederick Perkins, abandoned the family shortly after her birth and she grew up in poverty and received very little formal education. Her aunts, Isabella Beecher Hooker, a suffragist, and Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom's Cabin, had a major influence on her upbringing.

In her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1935), she argued that her mother was not affectionate and to stop them from getting hurt, insisted she did not make close friends or read novels. Charlotte added that her mother only showed affection only when she thought her young daughter was asleep.

In 1878 she briefly attended classes at the Rhode Island School of Design, and supported herself as a painter of trade cards. During her studies she met local artist, Charles Walter Stetson and the couple were married in 1884. A daughter was born the following year but soon afterwards "she fell into extreme despondence, leading to near nervous collapse."

The couple moved to Pasadena but in 1890 Stetson returned to Rhode Island to look after his mother. Charlotte began writing stories and articles for various journals including the New England Magazine. This included the publication of her most important story, The Yellow Wallpaper. Published in January 1892, recounts her own mental breakdown. She later claimed she wrote the story how women's lack of autonomy is detrimental to their mental, emotional and physical well being.

In 1892 she gained a divorce and returned her daughter to the care of her husband. In 1894, Gilman sent her daughter to live with her husband and his second wife, Grace Ellery Channing. Charlotte later explained that her daughter "had a right to know and love her father."

Charlotte continued to write stories and articles for various journals. She also gave lectures on women's suffrage and trade unions. In 1895 she settled in Chicago where she lived with Jane Addams, Ellen Gates Starr and Julia Lathrop in Hull House.

Charlotte was greatly influenced by the work of Edward Bellamy and became a socialist. She joined the Socialist Labor Party and in 1896 she was a delegate to the International Socialist Congress in London. While in England she met leading socialists such as Keir Hardie, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb and George Bernard Shaw. As her biographer, Mari Jo Buhle, has pointed out: "As her reputation spread and she became known for her discussion of women's topics as well, she devoted most of her time to the national lecture circuit."

In 1898 Charlotte published Women and Economics where she advocated equal work for women. In the book she criticized men for desiring weak and feeble wives and urged the economic independence of women. This was followed by other books on social issues such as Concerning Children (1900), The Home (1903) and Human Work (1904).

In 1900 Charlotte married her cousin, George Houghton Gilman. The couple moved to Norwich, Connecticut, whe she continued to campaign for women's rights and in 1909 founded Forerunner, a literary journal devoted to contemporary social issues. Most of the journal was written by Charlotte and she addressed questions of private morality, such as prostitution, social diseases and marriage.

Perkins also wrote several novels including What Diantha Did (1910), Herland (1915) and With Her in Ourland (1916). These novels illustrated her feminism and in many of her stories the traditional sex roles are reversed. Herland, considered to be her most impressive novel, is about a community of women without men.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Perkins and a group of women pacifists in the United States, began talking about the need to form an organization to help bring it to an end. On the 10th January, 1915, over 3,000 women attended a meeting in the ballroom of the New Willard Hotel in Washington and formed the Woman's Peace Party. Jane Addams was elected chairman and other women involved in the organization included Mary McDowell, Florence Kelley, Alice Hamilton, Anna Howard Shaw, Belle La Follette, Fanny Garrison Villard, Emily Balch, Jeanette Rankin, Lillian Wald, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Crystal Eastman, Carrie Chapman Catt, Emily Bach, and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

Perkins continued to write and other books published included His Religion and Hers: A Study of the Faith of Our Fathers and the Work of Our Mothers (1923), Our Changing Morality (1930) and a autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1935).

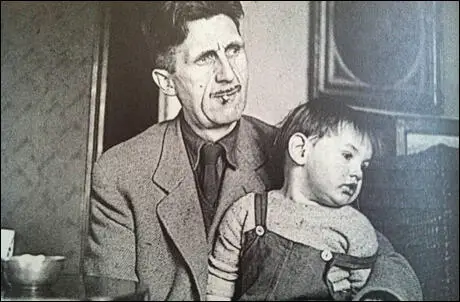

On this day in 1945 the novella Animal Farm by George Orwell is first published. The book was a satire in fable form of the communist revolution in Russia. The book, heavily influenced by his experiences of the way communists behaved during the Spanish Civil War, upset many of his left-wing friends and his former publisher, Victor Gollancz, rejected it. Published in 1945, the novel became one of Britain's most popular books.

His friend, A. J. Ayer, pointed out: "Though he held no religious belief, there was something of a religious element in George's socialism. It owed nothing to Marxist theory and much to the tradition of English Nonconformity. He saw it primarily as an instrument of justice. What he hated in contemporary politics, almost as much as the abuse of power, was the dishonesty and cynicism which allowed its evils to be veiled. When I first got to know him, he had written but not yet published Animal Farm, and while he believed that the book was good he did not foresee its great success. He was to be rather dismayed by the pleasure that it gave to the enemies of any form of socialism, but with the defeat of fascism in Germany and Italy he saw the Russian model of dictatorship as the most serious threat to the realization of his hopes for a better world."

On this day in 1987 Rudolf Hess was in Spandau Prison when he was found dead. Officially he committed suicide but grave doubts have been raised about the possibility of a 93 man in his state of health being able to hang himself with an electrical extension cord without help from someone else.

Rudolf Hess, the son of a wealthy German merchant, was born in Alexandria, Egypt on 26th April, 1894. At the age of twelve Hess was sent back to Germany to be educated at Godesberg. He later joined his father's business in Hamburg.

Hess joined the German Army in August, 1914, and served in the 1st Bavarian Infantry Regiment during the First World War. He was twice wounded and reached the rank of lieutenant. In 1918 became an officer pilot in the German Army Air Service.

After the war Hess settled in Munich where he entered the university to study history and economics. During this period he was greatly influenced by the teachings of Karl Haushofer, who argued that the state is a biological organism which grows or contracts, and that in the struggle for space the strong countries take land from the weak. This inspired Hess to write a prize-winning essay: How Must the Man be Constructed who will lead Germany back to her Old Heights? It included the following passage: "When necessity commands, he does not shrink from bloodshed... In order to reach his goal, he is prepared to trample on his closest friends."

Hess joined the Freikorps led by Franz Epp and helped to put down the Spartakist Rising during the German Revolution in 1919. The following year he heard Adolf Hitler speak at a political meeting. Hess remarked: "Was this man a fool or was he the man who would save all Germany."

Hess was one of the first people to join the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) and soon became a devoted follower and intimate friend of Adolf Hitler.

In November, 1923, Hess took part in the failed Beer Hall Putsch. Hess escaped and sought the help of Karl Haushofer. For a while he lived in Haushofer's home, Hartschimmelhof, in the Bavarian Alps. Later he was helped to escape to Austria. Hess was eventually arrested and sentenced to 18 months in prison. While in Landsberg he helped Hitler write My Struggle (Mein Kampf). According to James Douglas-Hamilton (Motive for a Mission) Haushofer provided "Hitler with a formula and certain well-turned phrases which could be adapted, and which at a later stage suited the Nazis perfectly".

Heinrich Bruening and other senior politicians were worried that Adolf Hitler would use his stormtroopers to take power by force. Led by Ernst Roehm, it now contained over 400,000 men. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles the official German Army was restricted to 100,000 men and was therefore outnumbered by the SA. In the past, those who feared communism were willing to put up with the SA as they provided a useful barrier against the possibility of revolution. However, with the growth in SA violence and fearing a Nazi coup, Bruening banned the organization.

In May 1932, Paul von Hindenburg sacked Bruening and replaced him with Franz von Papen. The new chancellor was also a member of the Catholic Centre Party and, being more sympathetic to the Nazis, he removed the ban on the SA. The next few weeks saw open warfare on the streets between the Nazis and the Communists during which 86 people were killed.

In an attempt to gain support for his new government, in July Franz von Papen called another election. Adolf Hitler now had the support of the upper and middle classes and the NSDAP did well winning 230 seats, making it the largest party in the Reichstag. However the German Social Democrat Party (133) and the German Communist Party (89) still had the support of the urban working class and Hitler was deprived of an overall majority in parliament.

Hitler demanded that he should be made Chancellor but Paul von Hindenburg refused and instead gave the position to Major-General Kurt von Schleicher. Hitler was furious and began to abandon his strategy of disguising his extremist views. In one speech he called for the end of democracy a system which he described as being the "rule of stupidity, of mediocrity, of half-heartedness, of cowardice, of weakness, and of inadequacy."

Rudolf Hess gradually worked his way up the Nazi hierarchy and in December 1932 Adolf Hitler appointed him head of the Central Political Committee and deputy leader of the party and minister without portfolio. Joseph Goebbels described Hess as "the most decent, quiet, friendley, clever, reserved... he is a kind fellow." Joachim C. Fest (The Face of the Third Reich) argued that many Germans thought he was an "honest man" and "the conscience of the Party".

The behaviour of the NSDAP became more violent. On one occasion 167 Nazis beat up 57 members of the German Communist Party in the Reichstag. They were then physically thrown out of the building. The stormtroopers also carried out terrible acts of violence against socialists and communists. In one incident in Silesia, a young member of the KPD had his eyes poked out with a billiard cue and was then stabbed to death in front of his mother. Four members of the SA were convicted of the rime. Many people were shocked when Hitler sent a letter of support for the four men and promised to do what he could to get them released.

Incidents such as these worried many Germans, and in the elections that took place in November 1932 the support for the Nazi Party fell. The German Communist Party made substantial gains in the election winning 100 seats. Hitler used this to create a sense of panic by claiming that German was on the verge of a Bolshevik Revolution and only the NSDAP could prevent this happening.

A group of prominent industrialists who feared such a revolution sent a petition to Paul von Hindenburg asking for Hitler to become Chancellor. Hindenberg reluctantly agreed to their request and at the age of forty-three, Hitler became the new Chancellor of Germany.

Although Adolf Hitler had the support of certain sections of the German population he never gained an elected majority. The best the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) could do in a election was 37.3 per cent of the vote they gained in July 1932. When Hitler became chancellor in January 1933, the Nazis only had a third of the seats in the Reichstag.

In the build up to the Second World War Hitler began to have growing doubts about the abilities of Hess and other leaders such as Hermann Göring, Heinrich Himmler, Joseph Goebbels and Martin Bormann became more important in the party. However, it is possible that Hess was playing a new secret role in Hitler's government.

Rochus Misch, Hitler's bodyguard, claims that in May 1941 he was at Berchtesgaden with Hitler and Hess. According to Misch: “He (Hitler) was talking to Hess, when somebody brought in a dispatch. The Führer read it and exclaimed: 'I cannot go there and go down on my knees!’ Hess replied: 'I can, my Führer.’ At the time a German diplomat was meeting the Swedish emissary, Count Bernadotte, in Portugal. The British were very active in Lisbon, so I think there might have been some peace offer from London.” It is impossible to know if Misch is right about this as the official British documents relating to it are still classified.

On 22nd May 1940 some 250 German tanks were advancing along the French coast towards Dunkirk, threatening to seal off the British escape route. Then, just six miles from the town, at around 11.30 a.m., they abruptly stopped. Adolf Hitler had personally ordered all German forces to hold their positions for three days. This order was uncoded and was picked up by the British. They therefore knew they were going to get away. German generals begged to be able to move forward in order to destroy the British army but Hitler insisted that they held back so that the British troops could leave mainland Europe.

Some historians have argued that this is an example of another tactical error made by Adolf Hitler. However, the evidence suggests that this was part of a deal being agreed between Germany and Britain. After the war, General Gunther Blumentritt, the Army Chief of Staff, told military historian Basil Liddell Hart that Hitler had decided that Germany would make peace with Britain. Another German general told Liddell Hart that Hitler aimed to make peace with Britain “on a basis that was compatible with her honour to accept”. (The Other Side of the Hill, pages 139-41)

According to Ilse Hess, her husband was told by Hitler that the massacring of the British army at Dunkirk would humiliate the British government and would make peace negotiations harder because of the bitterness and resentment it would cause. Joseph Goebbels recorded in his diary in June 1940 that Hitler told him that peace talks with Britain were taking place in Sweden. The intermediary was Marcus Wallenberg, a Swedish banker.

We know from other sources that Winston Churchill was under considerable pressure to finish off the peace talks that had been started by Neville Chamberlain. This is why George VI wanted Lord Halifax as prime minister instead of Churchill. There is an intriguing entry into the diary of John Colville, Churchill’s private secretary, on 10th May. In discussing Churchill’s talks with the king about becoming prime minister Colville writes: “Nothing can stop him (Churchill) having his way – because of his powers of blackmail”.

George VI was bitterly opposed to Winston Churchill becoming prime minister. He tried desperately to persuade Chamberlain to stay on in the job. When he refused he wanted to use his royal prerogative to appoint Lord Halifax as prime minister. Halifax refused as he feared this act would have brought the government down and would put the survival of the monarchy at risk. (John Costello, Ten Days that Saved the West, pages 46-47).

On 8th June 1940, one Labour MP suggested in the House of Commons that Churchill should instigate an inquiry into the “appeasement” party with a view to prosecuting its members. Churchill replied this would be foolish as “there are too many in it”. Hugh Dalton, Minister of Economic Warfare, recorded in his diary that the “appeasement party” was so powerful within the Conservative Party that Churchill faced the possibility of being removed as prime minister.

On 10th September 1940, Karl Haushofer sent a letter to his son Albrecht. The letter discussed secret peace talks going on with Britain. Karl talked about “middlemen” such as Ian Hamilton (head of the British Legion), the Duke of Hamilton and Violet Roberts, the widow of Walter Roberts. The Roberts were very close to Stewart Menzies (Walter and Stewart had gone to school together). Violet Roberts was living in Lisbon in 1940. Portugal, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland were the four main places where these secret negotiations were taking place. Karl and Albrecht Haushofer were close friends of both Rudolf Hess and the Duke of Hamilton.

Heinrich Stahmer, who worked with Haushofer, claimed that meetings between Samuel Hoare, Lord Halifax and Rudolf Hess took place in Spain and Portugal between February and April 1941. The Vichy press reported that Hess was in Spain on the weekend of 20/22 of April 1941. The correspondence between British Embassies and the Foreign Office are routinely released to the Public Record Office. However, all documents relating to the weekend of 20/22 April, 1941 at the Madrid Embassy are being held back and will not be released until 2017.

Karl Haushofer was arrested and interrogated by the Allies in October 1945. The British government has never released the documents that include details of these interviews. However, these interviews are in the OSS archive. Karl told his interviewers that Germany was involved in peace negotiations with Britain in 1940-41. In 1941 Albrecht was sent to Switzerland to meet Samuel Hoare, the British ambassador to Spain. This peace proposal included a willingness to “relinquish Norway, Denmark and France”. Karl goes onto say: “A larger meeting was to be held in Madrid. When my son returned, he was immediately called to Augsburg by Hess. A few days later Hess flew to England.”

On 10th May, 1941, Hess flew a Me 110 to Scotland. When he parachuted to the ground he was captured by David McLean, of the Home Guard. He asked to be taken to Duke of Hamilton, the “middleman” mentioned in the earlier letter. In fact, Hamilton lived close to where Hess landed (Dungavel House). If Hamilton was the “middleman” who was he acting for. Was it George VI or Winston Churchill? Shortly afterwards Sergeant Daniel McBride and Emyr Morris, reached the scene and took control of the prisoner. Hess’s first words to them were: “Are you friends of the Duke of Hamilton? I have an important message for him.”

After the war Daniel McBride attempted to tell his story of what had happened when he captured Hess. This story originally appeared in the Hongkong Telegraph (6th March, 1947). “The purpose of the former Deputy Fuhrer’s visit to Britain is still a mystery to the general public, but I can say, and with confidence too, that high-ranking Government officials were aware of his coming.” The reason that McBride gives for this opinion is that: “No air-raid warning was given that night, although the plane must have been distinguished during his flight over the city of Glasgow. Nor was the plane plotted at the anti-aircraft control room for the west of Scotland.” McBride concludes from this evidence that someone with great power ordered that Hess should be allowed to land in Scotland. This story was picked up by the German press but went unreported in the rest of the world.

According to Lieutenant-Colonel Malcolm Scott, Hess had told one of his guards that “members of the government” had known about his proposed trip to Scotland. Hess also asked to see George VI as he had been assured before he left Nazi Germany that he had the “King’s protection”. The authors of Double Standards, believe the Duke of Kent, the Duke of Hamilton, Samuel Hoare and Lord Halifax, were all working for the king in their efforts to negotiate with Adolf Hitler.

Karlheinz Pintsch, Hess adjutant, was given the task of informing Hitler about the flight to Scotland. James Leasor found him alive in 1955 and used him as a major source for his book, The Uninvited Envoy. Pintsch told Leasor of Hitler’s response to this news. He did not seem surprised, nor did he rant and rave about what Hess had done. Instead, he replied calmly, “At this particular moment in the war that could be a most hazardous escapade.”

Hitler then went onto read the letter that Hess had sent him. He read the following significant passage out aloud. “And if this project… ends in failure… it will always be possible for you to deny all responsibility. Simply say I was out of my mind.” Of course, that is what both Hitler and Churchill did later on. However, at the time, Hitler at least, still believed that a negotiated agreement was possible.

Raymond Gram Swing of the Chicago Daily News was invited to Chequers two months after Hess arrived in Scotland. In his autobiography, Good Evening (1964) he explained: "After the meal, the Prime Minister invited me to take a walk with him in the garden. This turned out to be the occasion for an unexpected and, I must say, somewhat disconcerting exposition to me of the terms on which Britain at that time could make a separate peace with Nazi Germany. The gist of the terms was that Britain could retain its empire, which Germany would guarantee, with the exception of the former German colonies, which were to be returned. The timing of this conversation seemed to me significant. Rudolf Hess, the number-three Nazi, had landed by parachute in Scotland less than two months before, where he had attempted to make contact with the Duke of Hamilton, whom the Nazis believed to be an enemy of Mr. Churchill and his policies... Mr. Churchill said nothing to me about Herr Hess. But he expounded to me the advantage of the German terms; and he seemed to be trying to arouse in me a feeling that unless the United States became more actively involved in the war, Britain might find it to her interest to accept them. I may be ascribing to him intentions he did not have. Later I was to learn that Hitler himself had proposed broadly similar terms to Britain before the war actually began. But I was under the impression that the allurements of peace had been recently underlined by Rudolf Hess... But it troubled me to have him give me his exposition, which must have lasted a full twenty minutes. For my part, I believed that the United States's interests made our entry in the war imperative. But I did not believe it would spur the country to come in to be told that if it did not, Winston Churchill would make a separate peace with Hitler and put his empire under a Hitler guarantee of safety."

Eventually Adolf Hitler became convinced that Winston Churchill would refuse to do a deal. Karlheinz Pintsch was now a dangerous witness and he was arrested and was kept in solitary confinement until being sent to the Eastern Front. Hitler also issued a statement pointing out that "Hess did not fly in my name." Albert Speer, who was with Hitler when he heard the news, later reported that "what bothered him was the Churchill might use the incident to pretend to Germany's allies that Hitler was extending a peace feeler."

It was not until 27th January 1942 that Winston Churchill made a statement in the House of Commons about the arrival of Hess. Churchill claimed it was part of a plot to oust him from power and “for a government to be set up with which Hitler could negotiate a magnanimous peace”. If that was the case, were the Duke of Kent and the Duke of Hamilton part of this plot?

In September, 1943, Anthony Eden, the foreign secretary, admitted in the House of Commons that Hess had indeed arrived in Scotland to negotiate a peace settlement. However, Eden claimed that the British government had been unaware of these negotiations. In fact, he added, Hess had refused to negotiate with Churchill. Eden failed to say who Hess was negotiating with. Nor did he explain why Hess (Hitler) was willing to negotiate with someone other than the British government. The authors of Double Standards argue that Hess was negotiating with Duke of Hamilton and the royal family, via the Duke of Kent. It is true Hamilton had a meeting with Churchill and Stewart Menzies two days after Hess arrived in Scotland. We also know that MI6 was monitoring these negotiations. If Hamilton was truly a traitor, surely Churchill would have punished him. Instead, along with the Duke of Kent, who were both in the RAF, were promoted by Churchill. In July 1941 Hamilton became a Group Captain and Kent became an Air Commodore.

This did not stop journalists speculating that the Duke of Hamilton was a traitor. In February 1942, Hamilton sued the London District Committee of the Communist Party for an article that appeared in their journal, World News and Views. The article claimed that Hamilton had been involved in negotiating with Nazi Germany and knew that Hess was flying to Scotland. Had this information come from Kim Philby? The case was settled when the Communist Party issued a public apology. Clearly, they could not say where this information came from.

Later that year Hamilton sued Pierre van Paassen, who in his book, That Day Alone, described Hamilton as a “British Fascist” who had plotted with Hess. The case was settled out of court in Hamilton’s favour. Sir Archibald Sinclair also issued a statement in the House of Commons that the Duke of Hamilton had never met Rudolf Hess.

However, recently released documents show that this was not all it seemed. The Communist Party threatened to call Hess as a witness. This created panic in the cabinet. A letter from the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, to Sir Archibald Sinclair, dated 18th June 1941, shows that the government was extremely worried about Hess appearing as a witness in this libel case. Morrison asks Sinclair to use his influence on Hamilton to drop the libel case. It is interesting that this letter was sent to Sinclair as he is the man who made the public statement about Hamilton and Hess, carried out the investigation into the Duke of Kent’s death and whose estate Hess was supposed to be living when the crash took place. Hamilton clearly took Morrison’s advice and this explains why the Communist Party did not have to pay any money to Hamilton over the libel.

The Pierre van Paassen’s case is also not as clear-cut as it appears. Hamilton sued him for $100,000. In fact, all Hamilton got was $1,300. The publisher had to promise that future editions of the book would have to remove the offending passage. However, he did not have to recall and pulp existing copies of the book.

However, it is the third case that tells us most about what was going on. On 13th May 1941 the Daily Express published an article detailing the close relationship between the Duke of Hamilton and Rudolf Hess. The Duke’s solicitor had a meeting with Godfrey Norris, the editor of the newspaper. The solicitor later reported that Norris appeared willing to print a retraction. While the discussion was taking place Lord Beaverbrook, the proprietor of the newspaper, arrived. He overruled his editor and stated that the newspaper would stick to its accusation. Beaverbrook added that he could prove that Sir Archibald Sinclair lied when he claimed in the House of Commons that Hamilton had never met Rudolf Hess. Understandably, the Duke of Hamilton withdrew his threat to sue the Daily Express. (Anne Chisholm and Michael Davie, Beaverbrook, A Life, pages 409-10)

What is clear about these events is that Churchill and Sinclair made every attempt to protect the reputation of the Duke of Hamilton following the arrival of Hess. However, Beaverbrook, who like Hamilton was a prominent appeaser before the war, let him know that he was not in control of the situation.

After the war the Duke of Hamilton told his son that he was forced to take the blame for Hess arriving in Scotland in order to protect people who were more powerful than him. The son assumed he was talking about the royal family. It is possible he was also talking about Winston Churchill.

There are other signs that Hess had arrived to carry out serious peace negotiations with the British government.. On the very night that Rudolf Hess arrived in Scotland, London experienced its heaviest German bomb attack: 1,436 people were killed and some 12,000 made homeless. Many historic landmarks including the Houses of Parliament were hit. The Commons debating chamber – the main symbol of British democracy – was destroyed. American war correspondents based in London such as Walter Lippmann and Vincent Sheean, suggested that Britain was on the verge of surrender.

Yet, the 10th May marked the end of the Blitz. It was the last time the Nazis would attempt a major raid on the capital. Foreign journalist based in London at the time wrote articles that highlighted this strange fact. James Murphy even suggested that there might be a connection between the arrival of Hess and the last major bombing raid on London. (James Murphy, Who Sent Rudolf Hess, 1941 page 7)

This becomes even more interesting when one realizes at the same time as Hitler ordered the cessation of the Blitz, Winston Churchill was instructing Sir Charles Portal, Chief of the Air Staff, to reduce bombing attacks on Nazi Germany. Portal was surprised and wrote a memorandum to Churchill asking why the strategy had changed: “Since the Fall of France the bombing offensive had been a fundamental principle of our strategy.” Churchill replied that he had changed his mind and now believed “it is very disputable whether bombing by itself will be a decisive factor in the present war”. (John Terraine, The Right Line: The RAF in the European War 1939-45, 1985 page 295)

Is it possible that Hitler and Churchill had called off these air attacks as part of their peace negotiations? Is this the reason why Hess decided to come to Britain on 10th May, 1941? The date of this arrival is of prime importance. Hitler was no doubt concerned about the length of time these negotiations were taking. We now know that he was desperate to order the invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa) in early Spring. According to Richard Sorge of the Red Orchestra spy network, Hitler planned to launch this attack in May 1941. (Leopold Trepper, The Great Game, 1977, page 126)

However, for some reason the invasion was delayed. Hitler eventually ordered the invasion of the Soviet Union on 22nd June, 1941. It would therefore seem that peace negotiations between Germany and Britain had come to an end. However, is this true? One would have expected Churchill to order to resume mass bombing of Germany. This was definitely the advice he was getting from Sir Charles Portal, Chief of the Air Staff. Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris also took a similar view. In June 1943, Harris was briefing American journalists about his disagreement with Churchill’s policy.

Douglas Reed, a British journalist with a good relationship with Portal and Churchill, wrote in 1943: “The long delay in bombing Germany is already chief among the causes of the undue prolongation of the war.” (Douglas Reed, Lest We Regret, 1943, page 331). One senior army figure told a journalist after the war that Hess’s arrival brought about a “virtual armistice” between Germany and Britain.

Early in 1944, John Franklin Carter, who was in charge of an intelligence unit based in the White House, suggested to President Franklin D. Roosevelt a scheme developed by Ernst Hanfstaengl. He suggested that Hanfstaengl should be allowed to fly to England and meet with Hess. Roosevelt contacted Winston Churchill about this and then vetoed the scheme. According to Joseph E. Persico, the author of Roosevelt's Secret War (2001): "The British, he explained, were not going to let anyone question the possibly insane Nazi, who had recently hurled himself head-first down a flight of stairs."

On 6th November, 1944, Churchill made a visit to Moscow. At a supper in the Kremlin, Joseph Stalin raised his glass and proposed a toast to the British Intelligence Services, which he said had “inveigled Hess into coming to England.” Winston Churchill immediately protested that he and the intelligence services knew nothing about the proposed visit. Stalin smiled and said maybe the intelligence services had failed to tell him about the operation.

Rudolf Hess was kept in the Tower of London until being sent to face charges at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trial. On 13th November, 1945, American psychiatrist Dr Donald Ewen Cameron was sent by Allen Dulles of the OSS to assess Hess’s fitness to stand trial.

Cameron was carrying out experiments into sensory deprivation and memory as early as 1938. In 1943 he went to Canada and established the psychiatry department at Montreal's McGill University and became director of the newly-created Allan Memorial Institute that was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. At the same time he also did work for the OSS. It is almost certain that the US intelligence services were providing at least some of the money for his research during the war.

We know by 1947 he was using the “depatterning” technique to wipe out patients memories of the past. Donald Ewen Cameron believed that after inducing complete amnesia in a patient, he could then selectively recover their memory in such a way as to change their behaviour unrecognisably." In other words, Cameron was giving them a new past. Is it possible that Cameron and the OSS was doing this during the Second World War. Is it possible that the real reason for Cameron’s visit was that he wanted to assess the treatment he had been giving Hess since 1943? That Hess was one of Cameron’s guinea pigs.

When he came face to face with Hermann Göring at Nuremberg, Hess remarked: “Who are you”? Göring reminded him of events that they witnessed in the past but Hess continued to insist that he did not know this man. Karl Haushofer was then called in but even though they had been friends for twenty years, Hess once again failed to remember him. Hess replied “I just don’t know you, but it will all come back to me and then I will recognise an old friend again. I am terribly sorry.” (Peter Padfield, Hess: The Führer’s Disciple, page 305).

Hess did not recognise other Nazi leaders. Joachim von Ribbentrop responded by suggesting that Hess was not really Hess. When told of something that Hess had said he replied: “Hess, you mean Hess? The Hess we have here?” (J. R. Rees, The Case of Rudolf Hess, page 169).

However, Major Douglas M. Kelley, the American psychiatrist who was responsible for Hess during the trials, stated that he did have periods when he did remember his past. This included a detailed account of his flight to Scotland. Hess told Kelley that he had arrived without the knowledge of Hitler. Hess claimed that “only he could get the English King or his representatives to meet with Hitler and make peace so that millions of people and thousands of villages would be spared.” (J. R. Rees, The Case of Rudolf Hess, page 168).

The list of 23 defendants at Nuremberg included Rudolf Hess, Hermann Göring, Wilhelm Frick, Hans Frank, Rudolf Hess, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Alfred Rosenberg, Albert Speer, Julius Streicher, Alfred Jodl, Fritz Saukel, Robert Ley, Erich Raeder, Wilhelm Keitel, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, Hjalmar Schacht, Karl Doenitz, Franz von Papen, Constantin von Neurath and Joachim von Ribbentrop.

Robert Ley and Hermann Goering both committed suicide during the trial. Wilhelm Frick, Hans Frank, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Walther Funk, Fritz Saukel, Alfred Rosenberg, Julius Streicher, Alfred Jodl, Wilhelm Keitel, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, and Joachim von Ribbentrop were found guilty and executed on 16th October, 1946. Rudolf Hess, Erich Raeder, were sentenced to life imprisonment and Albert Speer to 25 years. Karl Doenitz, Walther Funk, Franz von Papen, Alfried Krupp, Friedrich Flick and Constantin von Neurath were also found guilty and sentenced to long terms of imprisonment at Spandau Prison.

In January, 1951, John McCloy, the US High Commissioner for Germany, announced that Alfried Krupp and eight members of his board of directors who had been convicted with him, were to be released. His property, valued at around 45 million, and his numerous companies were also restored to him.

Others that McCloy decided to free included Friedrich Flick, one of the main financial supporters of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). During the Second World War Flick became extremely wealthy by using 48,000 slave labourers from SS concentration camps in his various industrial enterprises. It is estimated that 80 per cent of these workers died as a result of the way they were treated during the war. His property was restored to him and like Krupp became one of the richest men in Germany.

Others serving life-imprisonment at Spandau Prison were also released: Erich Raeder (1955), Karl Doenitz (1956), Friedrich Flick (1957) and Albert Speer (1966). However, the Soviet Union and Britain refused to release Rudolf Hess.

However, Mikhail Gorbachev told German journalists in February 1987, that he was going to give permission for the release of Hess (Peter Padfield, Hess: The Führer’s Disciple, page 328). The West German newspaper Bild reported that Hess was going to be released on his 93rd birthday on 26th April 1987. (Bild, 21st April, 1987) Hess knew differently, he told Abadallah Melaouhi, his nurse, that the “English will kill me” before I am released. (BBC Newsnight, 28th February 1989).

According to Sir Christopher Mallaby, Deputy Secretary of the Cabinet Office, the British did indeed block his release. Gorbachev told Margaret Thatcher that he would expose the British hypocrisy by withdrawing the Soviet guards from Spandau Prison.