Ernst Röhm

Ernst Röhm, the son of a railway official, was born in Ingolstadt, Bavaria, on 28th November, 1887.

Röhm later complained that his father was domineering and harsh. In his memoirs he recalled that "from my childhood I had only one thought and wish - to be a soldier". (1)

Röhm joined the German Army in 1906 and two years later had reached the rank of lieutenant. He was described as "a fanatical, simple-minded swashbuckler" soldier and by the outbreak of the First World War he was a company commander. (2)

On 2nd June, 1916, Röhm was seriously wounded during an assault on Thiamont, part of the belt of fortifications at Verdun. He was "disfigured for life, his skin marked forever with the signs of his military vocation". (3)

The journalist, Konrad Heiden, later reported: "Three times wounded in the war, he returned each time to the front. Half his nose was shot away, he had a bullet hole in his cheek; short, stocky, shot to tatters, and patched, he was the outward image of a freebooter captain. He was more a soldier than an officer. In his memoirs he condemns the cowardice, sensuality, and other vices of many comrades; his revelations were almost treason against his own class." (4)

At the end of the war Röhm had reached the rank of captain. He was assigned to District Command VII in Munich. Röhm strongly believed that army officers should become involved in politics. Under his influence the army's special intelligence section was formed to maintain a watchful eye over the many political groups that were formed after the war. (5) As he pointed out in his memoirs, as a soldier "I was not willing to give up my right to political thought and action within the limits allowed by my military duty, and I made full use of it." (6)

At the end of the war left-wing socialists were in control in Bavaria, where Kurt Eisner, the leader of the Independent Socialist Party, had formed a coalition government with the Social Democratic Party. Eisner was assassinated by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley on 21st February, 1919. It is claimed that before he killed Eisner he said: "Eisner is a Bolshevist, a Jew; he isn't German, he doesn't feel German, he subverts all patriotic thoughts and feelings. He is a traitor to this land." (7)

Röhm arranged for right-wing opponents of the coalition government to receive arms and ammunition from the military. He later wrote: "Since I am an immature and wicked man, war and unrest appeal to be more than good bourgeois order." This included providing help to Colonel Franz Epp, the leader of the Freikorps in Bavaria. (8)

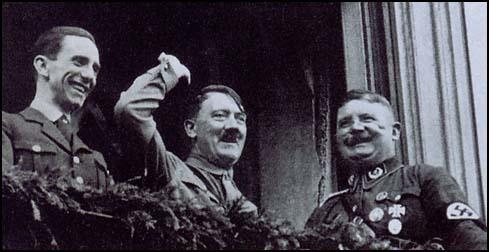

Ernst Röhm in Munich

On 7th March, 1919, Röhm met Adolf Hitler: "There, in that atmosphere of displaced fanaticism, he met a veteran of the Franco-German front, a pale and puny man with a look of exaltation in his eyes, fired by nationalist passion and visionary ambition, a magnetic orator who spoke in short, sharp bursts." Hitler later recalled that they spent the evening "in a cellar where we racked our brains for ways of combating the revolutionary movement". It is believed that night Hitler was recruited as a spy and informer on left-wing organisations. (9)

William L. Shirer, the author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1964) has argued: "He (Röhm) was a stocky, bull-necked, piggish-eyed, scar-faced professional soldier... with a flair for politics and a natural ability as an organizer. Like Hitler he was possessed of a burning hatred for the democratic Republic and the 'November criminals' he held responsible for it. His aim was to re-create a strong nationalist Germany and he believed with Hitler that this could be done only by a party based on the lower classes, from which he himself, unlike most Regular Army officers, had come. A tough, ruthless, driving man - albeit, like so many of the early Nazis, a homosexual." (10)

Hans Mend, who spent time with Hitler in Munich that year later claimed: "Hitler... made persistent attempts to obtain a senior position with the Communists, but he couldn't get into the Munich directorate of the Communist Party although he posed as an ultra-radical. Since he promptly requested a senior Party post that would have exempted him from the need to work - his perpetual aim - the Communists distrusted him despite his mortal hatred of all property owners." (11)

Ernst Röhm arranged for Colonel Franz Epp to receive a secret cache of weapons. Friedrich Ebert, the president of Germany, eventually arranged for 30,000 Freikorps, under the command of General Burghard von Oven, to overthrow the socialist government in Munich. They entered the city on 1st May 1919 and over the next two days the Freikorps easily defeated the Red Guards. (12)

Allan Mitchell, the author of Revolution in Bavaria (1965), pointed out: "Resistance was quickly and ruthlessly broken. Men found carrying guns were shot without trial and often without question. The irresponsible brutality of the Freikorps continued sporadically over the next few days as political prisoners were taken, beaten and sometimes executed." An estimated 700 men and women were captured and executed." (13)

Adolf Hitler was arrested with other soldiers in Munich and accused of being a socialist. Hundreds of socialists were executed without trial but Hitler was able to convince them that he had been an opponent of the regime. It seems almost certain that Ernst Röhm helped to protect him during this period. Hitler volunteered to help to identify soldiers who had supported the Socialist Republic.

On 30th May 1919 Major Karl Mayr was appointed as head of the Education and Propaganda Department. He was given considerable funds to build up a team of agents or informants and to organize a series of educational courses to train selected officers and men in "correct" political and ideological thinking. Mayr was also given the power to finance "patriotic" parties, publications and organizations. Captain Röhm was one of those who joined this unit. (14)

Röhm told Mayr about the abilities of Hitler. On 5th June 1919, Hitler began a course on political education at Munich University that had been organized by Mayr. Hitler attended courses entitled "German History Since the Reformation", "The Political History of the War", "Socialism in Theory and Practice", "our Economic Situation and Peace Conditions" and "The Connection between Domestic and Foreign Policy". (15)

The main aim was to promote his political philosophy favoured by the army and help to combat the influence of the Russian Revolution on the German soldiers. Speakers included Gottfried Feder and Karl Alexander von Müller. During one of Müller's lectures, Hitler was involved in a passionate debate with another student about Jews. Müller was impressed with Hitler's contribution and told Mayr that he had "rhetorical talent".

In September 1919, Hitler was ordered by the head of the Political Department to attend a meeting of the German Worker's Party (GWP). Formed by Anton Drexler, Hermann Esser, Gottfried Feder and Dietrich Eckart, the German Army was worried that it was a left-wing revolutionary group. (16)

Hitler recorded in Mein Kampf (1925): "When I arrived that evening in the guest room of the former Sternecker Brau (Star Corner)... I found approximately 20–25 persons present, most of them belonging to the lower classes. The theme of Feder’s lecture was already familiar to me; for I had heard it in the lecture course... Therefore, I could concentrate my attention on studying the society itself. The impression it made upon me was neither good nor bad. I felt that here was just another one of these many new societies which were being formed at that time. In those days everybody felt called upon to found a new Party whenever he felt displeased with the course of events and had lost confidence in all the parties already existing. Thus it was that new associations sprouted up all round, to disappear just as quickly, without exercising any effect or making any noise whatsoever." (17)

Hitler discovered that the party's political ideas were similar to his own. He approved of Drexler's German nationalism and anti-Semitism but was unimpressed with what he saw at the meeting. Hitler was just about to leave when a man in the audience began to question the logic of Feder's speech on Bavaria. Hitler joined in the discussion and made a passionate attack on the man who he described as the "professor". Drexler was impressed with Hitler and gave him a booklet encouraging him to join the GWP. Entitled, My Political Awakening, it described his objective of building a political party which would be based on the needs of the working-class but which, unlike the Social Democratic Party (SDP) or the German Communist Party (KPD) would be strongly nationalist. (18)

"In his (Feder's) little book he described how his mind had thrown off the shackles of the Marxist and trades-union phraseology, and that he had come back to the nationalist ideals. The pamphlet secured my attention the moment I began to read, and I read it with interest to the end. The process here described was similar to that which I had experienced in my own case ten years previously. Unconsciously my own experiences began to stir again in my mind. During that day my thoughts returned several times to what I had read; but I finally decided to give the matter no further attention." (19)

Drexler was impressed with Hitler's abilities as an orator and invited him to join the party. Hitler commented: "I didn't know whether to be angry or to laugh. I had no intention of joining a ready-made party, but wanted to found one of my own. What they asked of me was presumptuous and out of the question." However, Hitler was urged on by his commanding officer, Captain Karl Mayr, to join. Röhm also became a member of the GWP. Röhm, like Mayr, had access to the army political fund and was able to transfer some of the money into the GWP. (20)

Ernst Röhm became an important figure in the GWP. According to Konrad Heiden, a journalist who investigated the GWP: "Röhm was the secret head of a band of murderers. For his arsenal, he had men killed without the slightest qualm. In his inconspicuous position, he spent four years in Bavaria, secretly building up an army... He never wearies of praising the communists and their military qualities. Once he had him in his company, he assures us he could turn the reddest communist into a glowing nationalist in four weeks." (21)

Röhm was an openly gay man and was accused of using his power in the GWP to seduce young recruits. Joseph Goebbels, who held highly reactionary views about sexuality, later brought this information to the attention of Hitler, and was very surprised by his reaction: "Nauseating! The Party should not be an Eldorado for homosexuality. I will fight against that with all my power." (22)

In April 1920, the German Worker's Party (GWP) changed its name to the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). Hitler, therefore redefined socialism by placing the word "National" before it. He claimed he was only in favour of equality for those who had "German blood". Jews and other "aliens" would lose their rights of citizenship, and immigration of non-Germans should be brought to an end. Hitler became chairman of the new party and Karl Harrer was given the honorary title, Reich Chairman. (23)

On 24th February, 1921 the NSDAP (later nicknamed the Nazi Party) held a mass rally where it announced its new programme. The rally was attended by over 2,000 people, a great improvement on the 25 people who were at Hitler's first party meeting. Hitler knew that the growth in the party was mainly due to his skills as an orator and in the autumn of 1921 he challenged Anton Drexler for the leadership of the party. (24)

The NSDAP committee reported: "Adolf Hitler... regards the time as ripe for bringing dissension and schism into our ranks by means of the shadowy people behind him, and thus furthering the interests of the Jews and their friends. It grows more and more clear that his purposes is simply to use the National Socialist Party as a springboard for his own immoral purposes and to seize the leadership in order to force the Party on to a different track at the psychological moment." (25)

After brief resistance Drexler accepted the inevitable, and Hitler became the new leader of the Nazi Party. In September 1921, Hitler was sent to prison for three months for being part of a mob who beat up a rival politician. When Hitler was released, he formed his own private army called Sturm Abteilung (Storm Section). The SA (also known as stormtroopers or brownshirts) were instructed to disrupt the meetings of political opponents and to protect Hitler from revenge attacks. Röhm played an important role in recruiting these men, who were often former members of the Freikorps and had considerable experience in using violence against their rivals. (26)

Röhm's biographer, Paul R. Maracin, has pointed out that he played a vital role in arming the SA: "After the war a large arsenal was left by the German Army, and Röhm was one of several officers who conspired to divert and cache the arms. The German government had promised the Allies that the guns, ammunition, and vehicles would be dutifully destroyed, and according to the peace treaty, this should have been done. However, in some instances (with the connivance of some Allied officers attached to control commissions), these arms were stored for future use and would later he issued to members of the Freikorps and the SA. As an officer, Röhm had the reputation of a man who resolutely stood by his subordinates, while acting as a buffer between them and his superior officers. For all his dedication as a soldier, he was, paradoxically, a person who casually arranged for the murder of informants who tried to reveal the whereabouts of his hidden arsenals." (27)

In February 1923, with the help of Röhm, Adolf Hitler entered into negotiations with the Patriotic Leagues in Bavaria. This included the Lower Bavarian Fighting League, Reich Banner, Patriotic League of Munich and Oberland Defence League. A joint committee was set up under the chairmanship of Lieutenant Colonel Hermann Kriebel, the military leader of the Working Union of the Patriots Fighting Associations. Over the next few months Hitler and Rohm worked hard to bring in as many of the other right-wing groups as they could. (28)

Beer Hall Putsch

Gustav Stresemann, of the German National People's Party (DNVP), with the support of the Social Democratic Party, became chancellor of Germany in August 1923. On 26th September, he announced the decision of the government to call off the campaign of passive resistance in the Ruhr unconditionally, and two days later the ban on reparation deliveries to France and Belgium was lifted. He also tackled the problem of inflation by establishing the Rentenbank. (29)

Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) has pointed out: "This was a courageous and wise decision, intended as the preliminary to negotiations for a peaceful settlement. But it was also the signal the Nationalists had been waiting for to stir up a renewed agitation against the Government." (30) Hitler made a speech in Munich attacking Stresemann, as showing "subserviency towards the enemy, surrender of the human dignity of the German, pacifist cowardice, tolerance of every indignity, readiness to agree to everything until nothing remains." (31)

Röhm, Adolf Hitler, Hermann Göring and Hermann Kriebel had a meeting together on 25th September where they discussed what they were to do. Hitler told the men that it was time to take action. Röhm agreed and resigned his commission to give his full support to the cause. Hitler's first step was to put his own 15,000 Sturm Abteilung men in a state of readiness. The following day, the Bavarian Cabinet proclaimed a state of emergency and appointed Gustav von Kahr, one of the best-known politicians, with strong right-wing leanings, as State Commissioner with dictatorial powers. Kahr's first act was to ban Hitler from holding meetings. (32)

General Hans von Seeckt made it clear that he would take action if Hitler attempted to take power. As William L. Shirer, the author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1964), has pointed out: "He issued a plain warning to... Hitler and the armed leagues that any rebellion on their part would be opposed by force. But for the Nazi leader it was too late to draw back. His rabid followers were demanding action." (33)

Wilhelm Brückner, one of his SA commanders, urged him to strike at once: "The day is coming, when I won't be able to hold the men back. If nothing happens now, they'll run away from us." A plan of action was suggested by Alfred Rosenberg and Max Scheubner-Richter. The two men proposed to Hitler and Röhm that they should strike on 4th November during a military parade in the heart of Munich. The idea was that a few hundred storm troopers should converge on the street before the parading troops arrived and seal it off with machine-guns. However, when the SA arrived they discovered the street was fully protected by a large body of well-armed police and the plan had to be abandoned. It was then decided that the putsch should take place three days later. (34)

On 8th November, 1923, the Bavarian government held a meeting of about 3,000 officials. While Gustav von Kahr, the prime minister of Bavaria was making a speech, Adolf Hitler and 600 armed SA men entered the building. According to Ernst Hanfstaengel: "Hitler began to plough his way towards the platform and the rest of us surged forward behind him. Tables overturned with their jugs of beer. On the way we passed a major named Mucksel, one of the heads of the intelligence section at Army headquarters, who started to draw his pistol as soon as he saw Hitler approach, but the bodyguard had covered him with theirs and there was no shooting. Hitler clambered on a chair and fired a round at the ceiling." Hitler then told the audience: "The national revolution has broken out! The hall is filled with 600 armed men. No one is allowed to leave. The Bavarian government and the government at Berlin are hereby deposed. A new government will be formed at once. The barracks of the Reichswehr and the police barracks are occupied. Both have rallied to the swastika!" (35)

Leaving Hermann Göring and the SA to guard the 3,000 officials, Hitler took Gustav von Kahr, Otto von Lossow, the commander of the Bavarian Army and Hans von Seisser, the commandant of the Bavarian State Police into an adjoining room. Hitler told the men that he was to be the new leader of Germany and offered them posts in his new government. Aware that this would be an act of high treason, the three men were initially reluctant to agree to this offer. Adolf Hitler was furious and threatened to shoot them and then commit suicide: "I have three bullets for you, gentlemen, and one for me!" After this the three men agreed to become ministers of the government. (36)

Hitler dispatched Max Scheubner-Richter to Ludwigshöhe to collect General Eric Ludendorff. He had been leader of the German Army at the end of the First World War. Ludendorff had therefore found Hitler's claim that the war had not been lost by the army but by Jews, Socialists, Communists and the German government, attractive, and was a strong supporter of the Nazi Party. However, according to Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962): "He (Ludendorff) was thoroughly angry with Hitler for springing a surprise on him, and furious at the distribution of offices which made Hitler, not Ludendorff, the dictator of Germany, and left him with the command of an army which did not exist. But he kept himself under control: this was a national event, he said, and he could only advise the others to collaborate." (37)

While Adolf Hitler had been appointing government ministers, Ernst Röhm, leading a group of stormtroopers, had seized the War Ministry and Rudolf Hess was arranging the arrest of Jews and left-wing political leaders in Bavaria. Hitler now planned to march on Berlin and remove the national government. Surprisingly, Hitler had not arranged for the Sturm Abteilung (SA) to take control of the radio stations and the telegraph offices. This meant that the national government in Berlin soon heard about Hitler's putsch and gave orders to General Hans von Seeckt for it to be crushed. (38)

Gustav von Kahr, Otto von Lossow and Hans von Seisser, managed to escape and Von Kahr issued a proclamation: "The deception and perfidy of ambitious comrades have converted a demonstration in the interests of national reawakening into a scene of disgusting violence. The declarations extorted from myself, General von Lossow and Colonel Seisser at the point of the revolver are null and void. The National Socialist German Workers' Party, as well as the fighting leagues Oberland and Reichskriegsflagge, are dissolved." (39)

Wilhelm Brückner and Ernst Röhm in 1923

The next day Adolf Hitler, Hermann Kriebel, Eric Ludendorff, Julius Steicher, Hermann Göring, Max Scheubner-Richter, Walter Hewell, Wilhelm Brückner and 3,000 armed supporters of the Nazi Party marched through Munich in an attempt to join up with Röhm's forces at the War Ministry. At Odensplatz they found the road blocked by the Munich police. What happened next is in dispute. One observer said that Hitler fired the first shot with his revolver. Another witness said it was Steicher while others claimed the police fired into the ground in front of the marchers. (40)

William L. Shirer has argued: "At any rate a shot was fired and in the next instant a volley of shots rang out from both sides, spelling in that instant the doom of Hitler's hopes. Scheubner-Richter fell, mortally wounded. Goering went down with a serious wound in his thigh. Within sixty seconds the firing stopped, but the street was already littered with fallen bodies - sixteen Nazis and three police dead or dying, many more wounded and the rest, including Hitler, clutching the pavement to save their lives." (41)

Louis L. Snyder later commented: "In seconds 16 Nazis and 3 policeman lay dead on the pavement, and others were wounded. Goering, who was shot through the thigh, fell to the ground. Hitler, reacting spontaneously because of his training as a dispatch bearer during World War I, automatically hit the pavement when he heard the crack of guns. Surrounded by comrades, he escaped in a car standing close by. Ludendorff, staring straight ahead, moved through the ranks of the police, who in a gesture of respect for the old war hero, turned their guns aside." (42)

Hitler, who had dislocated his shoulder, lost his nerve and ran to a nearby car. Although the police were outnumbered, the Nazis followed their leader's example and ran away. Only Eric Ludendorff and his adjutant continued walking towards the police. Later Nazi historians were to claim that the reason Hitler left the scene so quickly was because he had to rush an injured young boy to the local hospital. (43)

Two hours after Hitler's march through the streets had been halted and dispersed by police bullets, Röhm realized the futility of the operation, surrendered, and was placed under arrest. Röhm, Adolf Hitler, Eric Ludendorff, Wilhelm Frick, Wilhelm Brückner, Hermann Kriebel, Walter Hewell, Friedrich Weber and Ernst Pöhner were also charged with high treason. If found guilty, they could faced the death penalty. The trial began on 26th February, 1924. The court-case created a great deal of interest and it was covered by the world's press. Hitler realized this was a good opportunity to speak to a large audience. (44)

Franz Gürtner, the Minister of Justice in Bavaria, was an old friend and protector of Hitler and he saw to it that he would be treated well in court: "Hitler was allowed to interrupt as often as he pleased, cross-examine witnesses at will and speak on his own behalf at any time and at any length - his opening statement consumed four hours, but it was only the first of many long harangues." (45)

Hitler argued in court: "One thing was certain, Lossow, Kahr, and Seisser had the same goal that we had - to get rid of the Reich Government with its present international and parliamentary government. If our enterprise was actually high treason, then during this whole period Lossow, Kahr, and Seisser must have been committing high treason along with us, for during all these weeks we talked of nothing but the aims of which we now stand accused.... I alone bear the responsibility, but I am not a criminal because of that. If today I stand here as a revolutionary, it is as a revolutionary against the Revolution. There is no such thing as high treason against the traitors of 1918." (46)

On the 1st April, 1924, the verdicts were announced. Eric Ludendorff was acquitted. Hitler, Weber, Kriebel and Pöhner were found guilty and were sentenced to five years' imprisonment. Röhm, although found guilty, was released and placed on probation. As Ian Kershaw has pointed out: "Even on the conservative Right in Bavaria, the conduct of the trial and sentences prompted amazement and disgust. In legal terms, the sentence was nothing short of scandalous. No mention was made in the verdict of the four policeman shot by the putschists; the robbery of 14,605 billion Marks was entirely played down; the destruction of the offices of the SPD newspaper Münchener Post and the taking of a number of Social Democratic city councillors as hostages were not blamed on Hitler." (47)

Hitler was sent to Landsberg Castle in Munich to serve his prison sentence. He was treated well and was allowed to walk in the castle grounds, wear his own clothes and receive gifts. Officially there were restrictions on visitors but this did not apply to Hitler, and a steady flow of friends, party members and journalists spent long spells with him. He was even allowed to have visits from his pet Alsatian dog. (48)

Ernst Röhm and Politics

Ernst Röhm was released on the day he was convicted. As the German historian, Rudolf Olden, has pointed out: "The indefatigable soldier at once started again at the very point where he had stopped: recruiting, drilling and holding parades... His conviction remained what it always had been: a soldier had to play his part in politics. Röhm did not understand that politics, in other words the leadership of a nation or a party, must be homogeneous; he believed in the necessity of dualism, of a duplication of functions." (49)

With the other leaders in prison, Röhm became the most significant figure in the Nazi Party. According to Kurt Ludecke, he was now working very closely with his lover, Edmund Heines. "Many of the men with whom I conferred were veritable condottieri (mercenaries)... Almost without exception they resumed Röhm's work eagerly, only too glad to be busy again at the secret military work without which they found life wearisome." (50)

Röhm, Alfred Rosenberg and Gregor Strasser, were anxious to take part in the national and State elections in the spring of 1924. Hitler, who was not a German citizen, was automatically excluded, and had from the beginning attacked all parliamentary activity as worthless and dangerous to the independence of the movement. Hitler was now concerned with the threat to his personal position as leader of the Party if others were elected to the Reichstag while he remained outside. Despite Hitler's opposition, supported by Julius Steicher and Hermann Esser, the Nazi Party did well in the elections, with Strasser, Röhm, Gottfried Feder, Wilhelm Frick and Erich Ludendorff winning seats. (51)

While his leader was in prison, Röhm made and attempt to increase his power. He wrote to Ludendorff suggesting that the SA should play a more important role in the Party. "The political and military movements are entirely independent of each other... As the present leader of the military movement I make the demand that the defence organizations should be given appropriate representation in the parliamentary group and that they should not be hindered in their special work." (52)

Röhm's biographer, Paul R. Maracin, has pointed out that after the election he experienced a scandal that caused him serious political problems: "He now entered the most difficult period of his life.... During 1924 Röhm endured the embarrassment of having his suitcase and personal papers stolen while he was consorting with questionable acquaintances in a sordid section of Berlin; as a result of this indiscretion, his homosexual proclivities became known to police authorities." (53)

Conflict with Adolf Hitler

In April 1925, Ernst Röhm came into conflict with Adolf Hitler. He complained that he could not stand the "flatterers" who "unscrupulously crowded around", exploiting his vanity, feeding him on illusions and "venturing no word of contradiction". Röhm decided "to speak openly to his friend as a loyal comrade". Hitler reacted badly and the two men had a vicious argument. Röhm wrote a letter to Hitler begging for the resumption of their old personal friendship, but Hitler did not answer. "Thus the real creator of Adolf Hitler parted with his creature who had grown too great and thought himself even greater." (54)

On 14th February 1926, Röhm attended the Bamberg Party Congress where Adolf Hitler attempted to settle to Nazi Party program. There had been a clash of opinion between northern and southern leaders about future policy. Röhm, Gregor Strasser and Joseph Goebbels represented the urban, socialist, revolutionary trend, whereas Gottfried Feder reflected rural, racialist and populist ideas. At the conference Hitler made a two-hour speech where he opposed the socialism of Röhm, Goebbels and Strasser. He argued that the NSDAP must not help Communist-inspired movements. (55)

Goebbels was initially appalled by the speech and noted in his diary: "I feel devastated... Hitler a reactionary? Amazingly clumsy and uncertain... Italy and England natural allies... Short discussion. Strasser speaks. Hesitant, trembling, clumsy, the good honest Strasser. God, how poor a match we are for those swine... Probably one of the greatest disappointments of my life. I no longer believe fully in Hitler." (56)

Goebbels and Strasser finally accepted these arguments and in return they received promotion. Strasser was appointed as Propaganda Leader of the NSDAP and Goebbels became Gauleiter of Berlin. However, Röhm made it clear that he still retained his faith in socialism. As a result Hitler removed him as leader of the Sturm Abteilung (SA) and replaced him with Franz Pfeffer von Salomon.

According to Michael Burleigh, the author of The Third Reich: A New History (2001): "Franz Felix Pfeffer von Salomon... brief was to check its aspirations to quasi-military status by firmly subordinating it to the Party's political and propaganda goals. The SA was to perform two functions: to rough up opponents during elections, a practice Hitler seems to have admired across the Atlantic, and to assert the Nazi presence on the streets." Hitler wrote to Pfeffer: "We have to teach Marxism that the future master of the streets is National Socialism, just as one day it will be master of the state." (57)

Paul R. Maracin claims that Röhm took this dismissal very badly. "Röhm... withdrew from political life, and failed miserably in his efforts to support himself. He drifted about, worked for a short period at a machine factory, became a book salesman, and imposed on his homosexual friends for sustenance. As a civilian, he was totally out of his element... Virtually destitute, he moved about in the lowest of circles and associated with the dregs of the social stratum.... In 1928 he briefly reconciled with Hitler and traveled throughout Germany renewing contacts with active duty Reichswehr officers as the party chief's envoy. After yet another dispute with Hitler, he abruptly left Germany for South America, accepting the post of military adviser to the Bolivian Army as a lieutenant-colonel. From Bolivia he imprudently sent letters to friends in Germany in which he decried the lack of understanding for homosexuals in that faraway land. Some of the letters addressed to Dr. Karl-Gunther Heimsoth fell into the hands of newspaper journalists and were given wide-spread publicity." (58)

Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) has argued that Pfeffer became just as difficult as Röhm had been. "Whatever steps Hitler took, however, the S.A. continued to follow its own independent course. Pfeffer held as obstinately as Röhm to the view that the military leadership should be on equal terms with, not subordinate to, the political leadership. He refused to admit Hitler's right to give orders to his Stormtroops. So long as the S.A. was recruited from the ex-service and ex-Freikorps men who had so far provided both its officers and rank and file, Hitler had to tolerate this state of affairs." (59)

Ernst Röhm and the Brownshirts

On 2nd September 1930 Hitler relieved Franz Pfeffer von Salomon of his command. Hitler assumed temporary leadership of the Sturmabteilung but decided to forgive Röhm for past indiscretions. A telegram was dispatched from Munich to La Paz. By the end of 1930 Röhm had returned to his native Germany, and in January 1931 he was named Chief of Staff of the SA. However, as one historian, Toby Thacker, points out, at the same time Hitler was negotiating with Röhm's enemies, industrialists and leaders of the German Army. (60) In just over a year Röhm expanded the SA from 70,000 to 170,000 members. (61)

Karl Ernst was a handsome young man and he attracted the attention of Ernst Röhm, who added him to his intimate circle of young men. On 4th April, 1931, Röhm promoted Karl Ernst to the post of supreme Sturmabteilung (SA) leader of Berlin. The following year Röhm arranged for Ernst to be elected to the Reichstag. Later he became SS-Gruppenführer (Lieutenant General) and was attached to the supreme leadership of the national SA. (62)

In the spring of 1931 the Berlin state attorney's office received a tip off about Ernst Röhm sexual behaviour. It probably came from one of his enemies in the Nazi Party. They started an investigation of Röhm for "unnatural offences" but it was eventually terminated for lack of evidence. Joseph Goebbels, now began spreading stories about Röhm in the hope of getting him dismissed. When he discovered what was going on, Röhm started rumours about Goebbels' relationship with Magda Quandt. He suggested that he "was interested less in Magda than in her young son." (63)

Adolf Hitler refused to sack Röhm and continued to use the brownshirts to break-up meetings held by the German Communist Party (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP). By 1932 there were nearly 2 million members of the SA and they easily won the "battle of the streets against the Communists". (64)

German journalists continued to investigate Röhm's sexual activities. Helmut Klotz, a former member of the Nazi Party, but now a supporter, of the SDP, published a pamphlet, The Röhm Case, where he produced evidence that Röhm was a homosexual. He pointed out that Hitler advocated the "castration of homosexuals" but "Captain Röhm... remains in his position as leader of young people." (65)

The SDP had 300,000 copies of this pamphlet published and a large number was sent to senior officials, officers, pastors, teachers, doctors, lawyers and journalists. The story was picked up by newspapers and several stories appeared about Röhm seducing young men in the SA. On 12th May 1932, in the lobby of the Reichstag, a group of Nazi deputies, led by Edmund Heines, beat up Klotz. The police were called and four of the Nazis were arrested. (66) The foreign press continued to report stories about the leader of the SA. Time Magazine commented that all Germany knew about this "greedy, sensual, plug-ugly face of... Ernst Röhm" and "his bull-like philandering with effeminate young men". (67)

Richard Walther Darré and Heinrich Himmler in January 1933.

When Hitler became Chancellor in 1933 Ernst Röhm made a speech where he stated: "A tremendous victory has been won. But not an absolute victory! The SA and the SS will not tolerate the German revolution going to sleep and being betrayed at the half-way stage by non-combatants. Not for the sake of the SA and SS but for Germany's sake. For the SA is the last armed force of the nation, the last defence against communism. If the German revolution is wrecked by the reactionary opposition, incompetence, or laziness, the German people will fall into despair and will be an easy prey for the bloodstained frenzy coming from the depths of Asia. If these bourgeois simpletons think that the national revolution has already lasted too long, for once we agree with them. It is in fact high time the national revolution stopped and became the National Socialist one. Whether they like it or not, we will continue our struggle - if they understand at last what it is about - with them; if they are unwilling - without them; and if necessary - against them."

By 1934 Hitler appeared to have complete control over Nazi Germany, but like most dictators, he constantly feared that he might be ousted by others who wanted his power. Albert Speer pointed out: "After 1933 there quickly formed various rival factions that held divergent views, spied on each other, and held each other in contempt. A mixture of scorn and dislike became the prevailing mood within the party. Each new dignitary rapidly gathered a circle of intimates around him. Thus Himmler associated almost exclusively with his SS following, from whom he could count on unqualified respect... As an intellectual Goebbels looked down on the crude philistines of the leading group in Munich, who for their part made fun of the conceited academic's literary ambitions. Göring considered neither the Munich philistines nor Goebbels sufficiently aristocratic for him and therefore avoided all social relations with them; whereas Himmler, filled with the elitist missionary zeal of the SS felt far superior to all the others." (68)

Hitler was especially afraid of Röhm and did not give him a post in his government. Röhm complained to Herman Rauschning: "Adolf is a swine... He only associates with the reactionaries now. His old friends aren't good enough for him. Getting matey with the East Prussian generals. They're his cronies now... Are we revolutionaries or aren't we? The generals are a lot of old fogies. They will never have a new idea... I don't know where he's going to get his revolutionary spirit from. They're the same old clods, and they'll certainly lose the next war." (69)

Industrialists such as Albert Voegler, Gustav Krupp, Alfried Krupp, Fritz Thyssen and Emile Kirdorf, who had provided the funds for the Nazi victory, were unhappy with Röhm's socialistic views on the economy and his claims that the real revolution had still to take place. Walther Funk reported that Hjalmar Schacht and his friends in big business were worried that the Nazis might begin "radical economic experiments". (70)

General Werner von Blomberg, Hitler's minister of war, and Walther von Reichenau, chief liaison officer between the German Army and the Nazi Party, became increasingly concerned about the growing power of Ernst Röhm and the Sturmabteilung (SA). They feared that the SA was trying to absorb the regular army in the same way that the SS had taken over the political police. (71) Reichenau was concerned by a letter he received from Röhm: "I regard the Reichswehr now only as a training school for the German people. The conduct of war, and therefore of mobilization as well, in the future is the task of the SA." (72)

Many people in the party disapproved of the fact that Röhm, and many other leaders of the SA, including his deputy, Edmund Heines, were homosexuals. Konrad Heiden, a German journalist who investigated these rumours later claimed that Heines was at the centre of this homosexual ring. "The perversion was wide-spread in the secret murderers' army of the post-war period, and its devotees denied that it was a perversion. They were proud, regarded themselves as 'different from the others', meaning better." (73)

However, Hitler allowed him to continue in his post. According to Ernst Hanfstaengel, during this period, Hitler was frightened of Röhm because Karl Ernst had information about the leader's sexuality: "Ernst, another homosexual SA officer, hinted in the early 1930s that a few words would have sufficed to silence Hitler had he complained about Röhm's behavior." (74)

Hermann Göring, Joseph Goebbels and Heinrich Himmler were all concerned with the growing power of Röhm, who continued to make speeches in favour of socialism. As Peter Padfield has pointed out, the Sturmabteilung (SA) "now a huge, heterogeneous and generally discontent army of four million, threatened the hereditary leadership of the Army, the Junker landowners, the bureaucracy, and the heavy industrialists" with talk of a second revolution. (75)

Rudolf Diels Report

Göring suggested to Rudolf Diels, the head of the Gestapo, that he was too close to Röhm. "I warn you, Diels, you can't sit on both sides of the fence." Göring ordered Diels to carry out an investigation into Röhm and the SA. He reported back with details of homosexual rings centering on Röhm and other SA leaders, and on their corruption of Hitler Youth members. Göring complained to Diels: "This whole camarilla around Chief of Staff Röhm is corrupt through and through. The SA is the pacemaker in all this filth (in the Hitler Youth movement). You should look into it more thoroughly." (76)

Diels presented his report to Adolf Hitler in January 1934 at his retreat at Obersalzberg. Diels provided information that Röhm had been conspiring with Gregor Strasser and Kurt von Schleicher against the government. It was also suggested that Röhm had been paid 12 million marks by the French to overthrow the Nazi government. (77) Hitler was furious and stated that "it is incomprehensible that Strasser and Schleicher, these arch-traitors, have survived to this day." After the meeting had ended Göring turned to Diels and said: "You understand what the Führer wants? These three must disappear and very soon." (78) He added that Strasser "can commit suicide - he is a chemist after all". (79)

Richard Overy has claimed that both Strasser and Von Schleicher were both politically inactive and posed no threat to Hitler. (80) Peter Stachura, the author of Gregor Strasser and the Rise of Nazism (1983) believes that Strasser was faithfully keeping a written promise to Hitler that he would renounce politics, shunning his former political associates and doing everything possible to deny rumours that he was involved in any conspiracy. (81)

Night of the Long Knives

In February, 1934, Hitler had a meeting with Group Captain Frederick Winterbotham. Hitler told him that there should be only three major powers in the world, the British empire, the American empire and the future German empire. "All we ask is that Britain should be content to look after her empire and not interfere with Germany's plans of expansion." He then went on to deal with the subject of Communism. "He stood up and, as if he was an entirely different personality, he started to yell in a high-pitched staccato voice... He ranted and raved against the Communists." It was later speculated that Hitler was letting Britain know he intended to purge the left-wing of the Nazi Party. (82)

Heinrich Himmler and Karl Wolff went to visit Ernst Röhm at the SA headquarters at the end of April. According to Wolff he "implored Röhm to dissociate himself from his evil companions, whose prodigal life, alcoholic excesses, vandalism and homosexual cliques were bringing the whole movement into disrepute". He then said with moist eyes, "do not inflict me with the burden of having to get my people to act against you". Röhm, also with tears in his eyes, thanked his old comrade for giving him this warning. (83)

On 4th June, 1934, Hitler held a five-hour meeting with Röhm. According to Hitler's account he told Röhm that he had heard that "certain conscienceless elements were preparing a Nationalist-Bolshevik revolution, which could lead only to miseries beyond description". Hitler informed Röhm that some people suspected that he was the leader of a group who "praise the Communist paradise of the future, which, in reality, would only lead to a battle for Hell." (84)

After the meeting Röhm told friends that he was convinced that he could rely on Hitler to take his side against "the gentlemen with uniforms and monocles". (85) Louis L. Snyder argues that Hitler had in fact decided to give his support to Röhm's enemies: "Hitler later alleged that his trusted friend Röhm had entered a conspiracy to take over political power. The Führer was told, possibly by one of Röhm's jealous colleagues, that Röhm intended to use the SA to bring a socialist state into existence... Hitler came to his final decision to eliminate the socialist element in the party." (86)

On 11th June 1934, Hjalmar Schacht had a private meeting with the Governor of the Bank of England, his personal friend and business associate, Montagu Norman. Both men were members of the Anglo-German Fellowship group and shared a "fundamental dislike" of the "French, Roman Catholics, Jews". (87) Schacht told Norman that there would be no "second revolution" and that the SA were about to be purged. (88)

Heinrich Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich, Hermann Göring and Theodore Eicke worked on drawing up a list of people who were to be eliminated. It was known as the "Reich List of Unwanted Persons". (89) The list included Ernst Röhm, Edmund Heines, Karl Ernst, Hans Erwin von Spreti and Julius Uhl of the SA, Gregor Strasser, Kurt von Schleicher, Hitler's predecessor as chancellor, Gustav von Kahr, who crushed the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, Herbert von Bose and Edgar Jung, two men who worked for Franz von Papen and Fritz Gerlich, a journalist who had investigated the death of Hitler's niece, Geli Raubal. (90)

Also on the list was Erich Klausener, the President of the Catholic Action movement, who had been making speeches against Hitler. It was feared that he was building up a strong following from within the Catholic Church. On 24th June, 1934, Klausener had organized a meeting held at Hoppegarten racecourse, where he spoke out against political oppression in front of an audience of 60,000. (91)

On the evening of 28th June, 1934, Hitler telephoned Röhm to convene a conference of the SA leadership at Hanselbauer Hotel in Bad Wiesse, two days later. "The call served the double purpose of gathering the SA chiefs in one out-of-the-way spot, and reassuring Röhm that, despite the rumours flying about, their mutual compact was safe. No doubt Röhm expected the discussion to centre on the radical change of government in his favour promised for the autumn." (92)

The following day Hitler held a meeting with Joseph Goebbels. He told him that he had decided to act against Röhm and the SA. Hitler felt he could not take the risk of "breaking with the conservative middle-class elements in the Reichswehr, industry, and the civil service". By eliminating Röhm he could make it clear that he rejected the idea of a "socialist revolution". Although he disagreed with the decision, Goebbels decided not to speak out against "Operation Humingbird" in case he was also eliminated. (93)

On 29th June, Karl Ernst got married and as he planned to go on his honeymoon and therefore could not attend the SA meeting at the Hanselbauer Hotel. Ernst Röhm and Hermann Göring both attended the wedding. (94) Later that day he alerted the Berlin SA that he had heard rumours that there was a danger of a putsch against Hitler by the right-wing of the party. (95)

At around 6.30 in the morning of 30th June, Hitler arrived at the hotel in a fleet of cars full of armed Schutzstaffel (SS) men. (96) Erich Kempka, Hitler's chauffeur, witnessed what happened: "Hitler entered Röhm's bedroom alone with a whip in his hand. Behind him were two detectives with pistols at the ready. He spat out the words; Röhm, you are under arrest. Röhm's doctor comes out of a room and to our surprise he has his wife with him. I hear Lutze putting in a good word for him with Hitler. Then Hitler walks up to him, greets him, shakes hand with his wife and asks them to leave the hotel, it isn't a pleasant place for them to stay in, that day. Now the bus arrives. Quickly, the SA leaders are collected from the laundry room and walk past Röhm under police guard. Röhm looks up from his coffee sadly and waves to them in a melancholy way. At last Röhm too is led from the hotel. He walks past Hitler with his head bowed, completely apathetic." (97)

Edmund Heines was found in bed with his chauffeur and other SA men were found in compromising situations. Heines and his boyfriend were dragged out and shot on the road. (98) Joseph Goebbels complained about the "revolting, almost nauseating scenes". (99) At the Munich railroad station, the SA leaders were beginning to arrive. As they alighted from the incoming trains they were taken into custody by SS troops. It is estimated that about 200 senior SA officers were arrested during that day. All of them were taken to Stadelheim Prison. (100)

One of Röhm's boyfriends, Karl Ernst, and the head of the SA in Berlin, had just married and was driving to Bremen with his bride to board a ship for a honeymoon in Madeira. His car was overtaken by Schutzstaffel (SS) gunman, who fired on the car, wounding his wife and his chauffeur. Ernst was taken back to SS headquarters and executed later that day. (101)

A large number of the SA officers were shot as soon as they were captured but Adolf Hitler decided to pardon Röhm because of his past services to the movement. However, after much pressure from Göring and Himmler, Hitler agreed that Röhm should die. Himmler ordered Theodor Eicke to carry out the task. Eicke and his adjutant, Michael Lippert, travelled to Stadelheim Prison in Munich where Röhm was being held. Eicke placed a pistol on a table in Röhm's cell and told him that he had 10 minutes in which to use the weapon to kill himself. Röhm replied: "If Adolf wants to kill me, let him do the dirty work." (102)

According to Paul R. Maracin, the author of The Night of the Long Knives: Forty-Eight Hours that Changed the History of the World (2004): "Ten minutes later, SS officers Michael Lippert and Theodor Eicke appeared, and as the embittered, scar-faced veteran of verdun defiantly stood in the middle of the cell stripped to the waist, the two SS officers riddled his body with revolver bullets." Eicke later claimed that Röhm fell to the floor moaning "Mein Führer". (103)

Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary: "Executions nearly finished. A few more are necessary. That is difficult, but necessary... It is difficult, but is not however to be avoided. There must be peace for ten years. The whole afternoon with the Führer. I can't leave him alone. He suffers greatly, but is hard. The death sentences are received with the greatest seriousness. All in all about 60." (104)

Time Magazine reported that the men had been executed as a result of a conflict between the SS and SA. It claimed that Hermann Göring and Gustav Krupp had been involved in the conspiracy. It reported that "Röhm was shot in the back next day by a firing squad". The magazine also reported that the Nazi government insisted that Herbert von Bose had committed suicide "until it could no longer be concealed that his death was due to six bullets". (105)

Goebbels broadcast the Nazi account of the executions on 10th July. He thanked the German press for "standing by the government with commendable self-discipline and fair-mindedness" and accused the foreign press of issuing false reports so as to create confusion. He stated that these newspapers and magazines had been involved in a "campaign of lies" which he compared to the "atrocity-story campaign waged against Germany" during the First World War. (106)

Hitler made a speech where he stated that he acted as "the Supreme Justiciar of the German Volk" and had used this violence "to prevent a revolution". A retrospective law was passed to legitimize the murders. The German judiciary made no protest about the use of the law to legalize murder. These events, however, had a major impact on the outside world: "The killings of 30 June and succeeding days were also an important moment in the history of the Nazi movement. Before the people of Germany, and the outside world, the leaders of the Party were revealed as calculating killers." (107)

Aftermath

It is not known how many people were murdered between 30th June and 2nd July, when Hitler called off the killings. Hitler admitted to 76, but the real number is probably nearer 200 or 250. "Bodies were found in fields and woods for weeks afterwards and files of petitions from relatives of the missing remained active for months. What seems certain is that less than half were SA officers." (108)

Herman Rauschning argued that the execution of the leaders of the SA showed that Hitler believed that the German Army posed no real threat to his government: "They had got their wish: Röhm was removed. The independence of the Reichswehr was assured. That was enough for them. They had no use for civil unrest. They reserved the right to make a special investigation into the shooting of the two generals, von Schleicher, the former Reich Chancellor, and von Bredow. They allowed their one opportunity of shaking off the National Socialist yoke to go by. Without political insight, uncertain and vacillating in everything except their military calling, they were anxious to return as quickly as possible to ordered and regular activities. This failure of the high officials and officers, and also of the big industrial and agricultural interests, was symptomatic of their further attitude. They were no longer capable of any statesmanlike action. In every crisis, they would again be in the opposition, but would always recoil before the final step, the overthrow of the regime." (109)

Hitler told Albert Speer what happened at Bad Wiesse: "Hitler was extremely excited and, as I believe to this day, inwardly convinced that he had come through a great danger. Again and again he described how he had forced his way into the Hotel Hanselmayer in Wiessee - not forgetting, in the telling, to make a show of his courage: We were unarmed, imagine, and didn't know whether or not those swine might have armed guards to use against us. The homosexual atmosphere had disgusted him: In one room we found two naked boys! Evidently he believed that his personal action had averted a disaster at the last minute: I alone was able to solve this problem. No one else! His entourage tried to deepen his distaste for the executed SA leaders by assiduously reporting as many details as possible about the intimate life of Röhm and his following." (110)

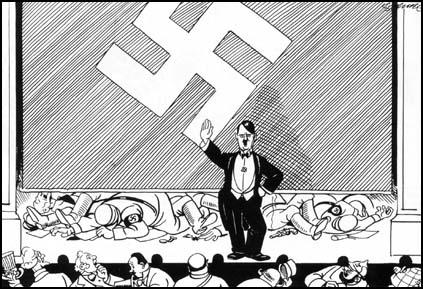

The purge of the SA was kept secret until it was announced by Hitler on 13th July. It was during this speech that Hitler gave the purge its name: Night of the Long Knives (a phrase from a popular Nazi song). Hitler claimed that 61 had been executed while 13 had been shot resisting arrest and three had committed suicide. Others have argued that as many as 400 people were killed during the purge. In his speech Hitler explained why he had not relied on the courts to deal with the conspirators: "In this hour I was responsible for the fate of the German people, and thereby I become the supreme judge of the German people. I gave the order to shoot the ringleaders in this treason."

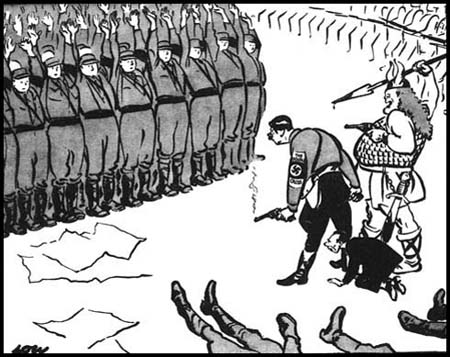

Sidney Strube, Daily Express (3rd July, 1934)

Heinrich Himmler made a speech to Gestapo officials on 11th October, 1934: "For us as Secret State Police and as members of the SS, 30 June was not - as several believe - a day of victory or a day of triumph, but it was the hardest day that can be visited on a soldier in his lifetime. To have to shoot one's own comrades, with whom one has stood side by side for eight or ten years in the struggle for an ideal, and who had then failed, is the bitterest thing which can happen to a man. For everyone who knows the Jews, freemasons and Catholics, it was obvious that these forces - who in the final analysis caused even 30 June in so much as they sent numerous individuals into the SA and the entourage of the former Chief of Staff and drove him to catastrophe - these forces were very much annoyed at the rout on 30 June. Because 30 June signified no more and no less than the detonation of the National Socialist state from within, blowing it up with its own people. There would have been chaos, and it would have given a foreign enemy the possibility of marching into Germany with the excuse that order had to be created in Germany." (111)

Joseph Goebbels later regretted the killing of Ernst Röhm: "I point out to the Führer at length that in 1934 we unfortunately failed to reform the Wehrmacht when we had an opportunity of doing so. What Röhm wanted was, of course, right in itself but in practice it could not be carried through by a homosexual and an anarchist. Had Röhm been an upright solid personality, in all probability some hundred generals rather than some hundred SA leaders would have been shot on 30 June. The whole course of events was profoundly tragic and today we are feeling its effects. In that year the time was ripe to revolutionize the Reichswehr." (112)

Primary Sources

(1) Paul R. Maracin, The Night of the Long Knives: Forty-Eight Hours that Changed the History of the World (2004)

War's end found him with the rank of captain, assigned to District Command VII in Munich. Contrary to what some of his professional fellow officers thought, he believed that army officers should be political activists; it is difficult to conceive of a more active one than Ernst Röhm. Through his work the army's special intelligence section was formed to maintain a watchful eye over the many political groups that proliferated after the end of hostilities. He eventually replaced Captain Mayr as head of the unit.

After the war a large arsenal was left by the German Army, and Röhm was one of several officers who conspired to divert and cache the arms. The German government had promised the Allies that the guns, ammunition, and vehicles would be dutifully destroyed, and according to the peace treaty, this should have been done. However, in some instances (with the connivance of some Allied officers attached to control commissions), these arms were stored for future use and would later be issued to members of the Freikorps and the SA. As an officer, Röhm had the reputation of a man who resolutely stood by his subordinates, while acting as a buffer between them and his superior officers.

For all his dedication as a soldier, he was, paradoxically, a person who casually arranged for the murder of informants who tried to reveal the whereabouts of his hidden arsenals.

It was Röhm - not Hitler - who first stumbled across the German Workers' Party, and it was Röhm who transformed that "talking club" (as one early writer described it) into a viable, fermenting hotbed of activists. It was Röhm who provided the infusion of restless, action-seeking (and action-producing) soldiers and former soldiers, thereby changing the original working-class character of the party. Röhm was already a member when Hitler discovered the party in the fall of 1919. He was impressed with Hitler's oratory, and was instrumental in putting Hitler in touch with politicians and military personnel who could be useful to the party. Without this assistance, it is doubtful that Hitler's political star could have risen so quickly.

The genesis of the SA dates back to the summer of 1920, when Emil Maurice, an ex-convict who later became Hitler's personal chauffeur, was placed in charge of a motley group of unruly party protectors. As a camouflage, in August 1921, they were called the "Gymnastic and Sports Division" of the party, and this transparent attempt to conceal the true purpose of the division was continued until October 1921 when it became known as the SA. Röhm was always the guiding light behind the SA, and it was his influence that brought in the militaristic recruits, his fine hand and expertise that restructured the SA into the formidable force it became in later years. It was Hitler who spouted the words; it was Rohm and his SA who provided the brawn to back them up.

During the latter part of September 1923, Röhm resigned from the Reichswehr and devoted all of his time to Hitler and the cause. Less than two months later he was deeply involved in the Beer Hall Putsch. He was the only leader in the coup d'etat who accomplished his objective: to seize the headquarters of the army at the War Ministry in Munich. Two hours after Hitler's march through the streets had been halted and dispersed by police bullets, Röhm realized the futility of the operation, surrendered, and was placed under arrest. He was one of the ten defendants tried for treason. While Hitler was sent to Landsberg Prison, Röhm (although found guilty) was placed on probation and released.

(2) Lothar Machtan, The Hidden Hitler (2001)

For the most part, however, Hitler continued to cling during 1919 to the authority whose 40 marks' army pay could at least enable him to keep his head above water: the military. He soon received some extra income from the same source. On March 7, 1919, he made the acquaintance of Captain Ernst Röhm - "in a cellar," as Hitler himself claimed later, "where we racked our brains for ways of combating the revolutionary movement. In all probability, this form of words was a euphemism for Hitler's employment as an informer by Rohm, who was then chief of staff to Epp, the Freikorps commander. Röhm had recently begun to recruit Bavarian mercenaries with the aid of a leaflet campaign."

Hitler's activities as an informer are attested by another source, which states that he had originally been hired by the intelligence service of that counterrevolutionary organization, and had there received his instructions from Rohm. Hitler is reputed to have been particularly close to Munich's revolutionary "soldiers' councils" in the spring of 1919 but only two months later he joined the 2nd Infantry's "discharge and fact-finding board," a body set up immediately after the counterrevolutionaries had triumphed. This job, which he would scarcely have obtained without Röhm's recommendation, entailed checking on the political convictions of comrades due for discharge.

Before long, Hitler was working for the intelligence department of Reichswehrgruppenkommando (military district headquarters) IV under Captain Karl May; once again as an informer. Mayr, who had quickly discerned Hitler's special ability in this sphere, employed him to systematically denounce politically unreliable officers and enlisted men.'' If Mayr's description of his "snitch" is correct, Hitler was very relieved to be offered a new "home,"" and he must have reacted in an extremely conformist and submissive manner. No book on Hitler has ever raised the question of what he really had to offer Mayr for the latter to protect him in this way. Nothing we know about that ambitious staff officer's life suggests that altruism could have been involved. In 1928 he coldly described Hitler as "an individual, paid by the month, from whom regular information could be expected." Mayr was an unscrupulous, go-getting secret service chief who, once the imperial regime had collapsed, wanted to help the counterrevolution to triumph at all costs. Thus there are only two possibilities: either he had personal reasons for making a protégé of Hitler, or he must have thought Hitler had a natural talent for spying and denunciation. The same goes for Röhm: already a devotee of the homoerotic aspects of militaristic nationalism, he sponsored Hitler in a quite exceptional manner.

(3) Konrad Heiden, Der Führer – Hitler's Rise to Power (1944)

The German Revolution of 1918-23 was not the great experience of the German people, but it was the great experience of its officers. A strange grey terror rose from the trenches and overpowered them. They began to study this terror and turn it to their own ends. Army and revolution entered upon a struggle for the source of power in modern society: the proletariat.

The educated worker, the intellectual of the fourth estate, is the strength of present-day armies. This proletarian worker, who more and more is becoming the actual intellectual of the technical age, is the human reservoir of modern society. Any militarism which does not want to die of malnutrition is dependent on him. The modern army is an army of technicians. The army needs the worker, and that is why it fights against the revolution; not for the throne and not for the money-bags, but for itself.

The army devours the people. A fatherland rises up within the fatherland.... Germany is: a tank park, a line of cannon, and the grey human personnel belonging to them. "I find", wrote one of those two hundred thousand officers in his autobiography, "that I no longer belong to this people. All I remember is that I once belonged to the German army."

The words are by Ernst Röhm. This Röhm, more than any other in his circle, is the key figure we were seeking when we asked: Who sent out the murderers? who gave the judges their orders? A young officer in his mid-thirties, a captain like a thousand others, the kind who might gladly and easily disappear in the mass, he stood modestly aside in the dazzling parades where generals and marshals, personally responsible, perhaps, for the loss of the war, were applauded by a misguided patriotic youth. Röhm was only an adjutant to the chief of the infantry troops stationed in Bavaria, a certain Colonel von Epp. But from this modest post he established, in defiance of the law and against the will of every Minister in Berlin and Munich, a volunteer army of a hundred thousand men, calling themselves modestly the Einwohnerwehr (citizens' defence). When this armed mass was finally disbanded by orders from above, he formed new nuclei. New organizations kept springing up, with all sorts of names, under constantly changing official leaders, all having ostensibly nothing to do with the Reichswehr. Actually all were an extension of the Reichswehr, under the command of Röhm.

Röhm was a professional soldier of petty bourgeois origin. His father was a middling railway official in Ingolstadt, Bavaria, where Röhm was born on November 28, 1887. The boy became an excellent soldier, the embodiment of personal bravery. In 1906 he joined the army, in 1908 became a lieutenant. Three times wounded in the war, he returned each time to the front. Half his nose was shot away, he had a bullet hole in his cheek; short, stocky, shot to tatters, and patched, he was the outward image of a freebooter captain. He was more a soldier than an officer. In his memoirs he condemns the cowardice, sensuality, and other vices of many comrades; his revelations were almost treason against his own class.

(4) Rudolf Olden, Hitler the Pawn (1936)

Röhm had also been convicted of high treason, but, together with others like him who were found guilty in a lesser degree, had been discharged on the day sentence was pronounced. The indefatigable soldier at once started again at the very point where he had stopped: recruiting, drilling and holding parades. Against the Notbann of Epp he set up a Frontbann which was to unite all the defence leagues.

His conviction remained what it always had been: a soldier had to play his part in politics. Röhm did not understand that politics, in other words the leadership of a nation or a party, must be homogeneous; he believed in the necessity of dualism, of a duplication of functions. His ideal was not modelled on Frederick the Great or Napoleon, the soldier-sovereign. He followed the example of Moltke and Ludendorff, who wanted only to guide and check the politicians, and not supplant them. He might have learnt a lesson from the events that followed the Great War. But clever and competent as he was, he could never grasp the main thing. He says, it is true, that he demands the chief position in the State for the soldier, but he cannot understand that in that case the soldier must be a politician, a political leader. No one has taught with greater insistence than Clausewitz that the Army must be subordinate to politics. Exactly like Ludendorff and the majority of German officers, Röhm studied the great Prussian military philosopher to little advantage.

Hitler never recognised military claims in his party. For this reason he always had to fight his military advisers. He required troops for political guerilla warfare, for his mass meetings and for service in the streets. He knew the magic influence that marching and fluttering banners exercise on the German mind, and in his propaganda campaign he could not do without them. He granted banners and military titles, founded brigades and divisions. But he never wanted to use them for anything except intimidation, and he was anxious to leave war preparations to the experts in the Army.

But Captain Röhm finally formulated his opposition in an ultimatum, a" demand " which he sent to Ludendorff, the leader of the entire völkisch movement. He wrote: "the political and military movements are entirely independent of one another. Both the political and the military movement are represented in the parliamentary group. As the present leader of the military movement, I demand that the defence leagues be granted appropriate representation in Parliament and that they be not hindered in their own particular work... Germany's liberty - at home and abroad - will never be won by mere chatter and bargaining; it must be fought for..." Nonsense that it was, it could not have been expressed more clearly.

(5) Konrad Heiden, Hitler: A Biography (1936)

Poor fatherland! You must entrust yourself to the wolves unless you want to go to the dogs. And it did not even help. At the second election, Hitler, though increasing his vote too 13,400,000, was again defeated by Hindenburg with 19,300,000. In the decisive hour Thaelmann was abandoned by many; his vote fell to approximately 3,500,000.

One thing was clear after these elections: the large majority of Germans were opposed to National Socialism. But nothing else was clear. It was plain what the country was against, but not what it was for. Nevertheless, the elections surely gave the Government a moral sanction to stamp out the smouldering flame of National Socialist civil war after so much hesitation. Groener was embittered; for many months he had believed firmly in Hitler's legality, he had even told him so publicly - and then suddenly the S.A. had drawn its ring around Berlin and armed for an attack on the arsenals of the Reichswehr.

But Schleicher had entirely different plans for the S.A., and not only for the S.A. In his conversations with Rohm a plan had matured by which both men had involved themselves in a treasonable plot, one against the State, the other against his party. The plan was to separate not only the S.A. but the other combat leagues from their parties by a sudden blow and put them under the jurisdiction of the State. At once Germany would have a "militia" numbering millions, with Schleicher as their General. If the General suddenly felt that his chief, Groener, was in his way, Röhm had almost the same feeling towards Adolf Hitler. Röhm had become more and more open and confiding. towards Schleicher; he had played Hitler into Schleicher's hands by telling him a number of unrepeatable stories about his Führer; in conversation with third parties, Schleicher boasted of knowing the most gruesome details.

Röhm was convinced that Germany was approaching a period of pure military rule; and not only Germany. In every country, he thought, there was a nucleus of soldierly men with an inner bond between them. It was immaterial under what party banners they had previously marched. For the parties were associations of shopkeepers; they had grown out of bourgeois interests and bourgeois experience; they pursued the aims of a peaceful world that seemed to be doomed, and consequently they were obsolete. This might be equally true of the National Socialist Party organization, to which Hitler had firmly welded the S.A. Now the party had again been defeated in an election, and perhaps Hitler's course would turn out to be wrong. Then it would be the hour of the S.A. Civil war was hanging over the country. If Röhm had known Nietzsche better, he might have recognized his own dreams in the philosopher's prophecy of rising European nihilism.

The unusual step which Röhm now took was probably taken with the knowledge, even the wish, of Schleicher. Röhm opened negotiations with the "Iron Front". Among its leaders there was a man who had once worked closely with Röhm, and who, like Röhm, might have called himself one of the inventors of Adolf Hitler. This was Karl Mayr, a former major in the Reichswehr. He had been a captain in that information section of the Munich Reichswehr which had sent out Hitler as its civilian employee, first to spy on the inner enemy, then to speak to the people in the streets and squares. Mayr, a true genius in the department that military men euphemistically call "information service", had a few years later broken with the Reichswehr and all his political friends. He had gone over to Social Democracy, had helped to build up the Reichsbanner, perhaps in the conviction that this was the right way to create a people's army.

When a new leadership transformed the Reichsbanner into the "Iron Front", Mayr vanished from the central leadership, but continued in his own way to work in the ranks. Rohm now turned to this old comrade. Was there no way, he asked, of bringing the S.A. and the Iron Front together, of getting rid of the useless political windbags and "making the soldier master of Germany"?

Röhm was shrewd enough not to keep the conversation secret from Hitler. The interview took place in Mayr's apartment, and with all the trappings of a spy movie; behind a curtain sat a lady taking shorthand notes. Mayr asked Röhm what grounds he had for thinking that he could detach the S.A. from the party. Röhm replied that he knew he had powerful and dangerous enemies in the party; Mayr's comment on this was: Would you like me to tell you the name of your future murderers? At that time Röhm's wild homosexual life had become fully public; there was great bitterness in the ranks against this leader who brought shame to the organization; Hitler had defiantly covered Röhm. "Captain Röhm", he said, "remains my Chief of Staff, now and after the elections, despite all slanders." The underground hostility to him was all the bitterer. A few months later, a Munich court actually did sentence two obscure National Socialists, Horn and Danzeisen, to short jail terms for having talked of murdering the Chief of Staff; but the court believed them when they said that it had been mere talk.

The conversation between Röhm and Mayr seems likewise to have gone no farther than talk, because Mayr had lost his influence on the Iron Front.

(6) Ernst Röhm, article published about Adolf Hitler becoming Chancellor of Germany (June, 1933)

A tremendous victory has been won. But not an absolute victory! The SA and the SS will not tolerate the German revolution going to sleep and being betrayed at the half-way stage by non-combatants. Not for the sake of the SA and SS but for Germany's sake. For the SA is the last armed force of the nation, the last defence against communism. If the German revolution is wrecked by the reactionary opposition, incompetence, or laziness, the German people will fall into despair and will be an easy prey for the bloodstained frenzy coming from the depths of Asia.

If these bourgeois simpletons think that the national revolution has already lasted too long, for once we agree with them. It is in fact high time the national revolution stopped and became the National Socialist one. Whether they like it or not, we will continue our struggle - if they understand at last what it is about - with them; if they are unwilling - without them; and if necessary - against them.

(7) Comments made by Ernst Röhm to Herman Rauschning about Adolf Hitler in May, 1933.

Adolf is a swine... He only associates with the reactionaries now. His old friends aren't good enough for him. Getting matey with the East Prussian generals. They're his cronies now... Are we revolutionaries or aren't we? The generals are a lot of old fogies. They will never have a new idea... I don't know where he's going to get his revolutionary spirit from. They're the same old clods, and they'll certainly lose the next war.

(8) Comments made by Ernst Röhm to Kurt Ludecke (January, 1934)

Hitler can't walk over me as he might have done a year ago; I've seen to that. Don't forget that I have three million men, with every key position in the hands of my own people, Hitler knows that I have friends in the Reichswehr, you know! If Hitler is reasonable I shall settle the matter quietly; if he isn't I must be prepared to use force - not for my sake but for the sake of our revolution.

(9) Time Magazine (20th March, 1933)

In Munich polite siege was laid to the State Government of Catholic Premier Dr. Heinrich Held of Tiavaria by apple-cheeked youngsters trying to look grim in their brown shirt uniforms. They were led by Captain Ernst Röhm, the National Storm Troops' queer sub-commander. Premier Held, reluctant to have dealings with such a person as Captain Röhm, nevertheless accepted a decree signed by President von Hindenburg (under his emergency powers to seize any part of Germany "if there be danger of Communist excesses").

About 4 p. m., when Captain Röhm again called on Dr. Held, the Premier resigned after stating the fact that "conditions for the application of this decree are completely lacking, because peace and order and prevention of Communist excesses are secured beyond a doubt by the resources of the State."

Ousted ex-Premier Held telegraphed to the Berlin Dictator his protest and abhorrence of Dictator Hitler's methods. Then, clapping on his hat, he walked out through serried ranks of Captain Röhm's young men.

In Nazi eyes nudism is a vice to be exterminated at all costs. Some 500,000 Germans, male & female, belong to nudist clubs. Suppressing them all by a single, nation-wide order, Nazi Minister-Without-Portfolio Hermann Wilhelm Goring denounced "the so-called cult of nudism" as "one of the greatest dangers to German culture and morals."

"In women," said Herr Goring, "nudism deadens the sense of shame, and in men it destroys respect for womanhood."