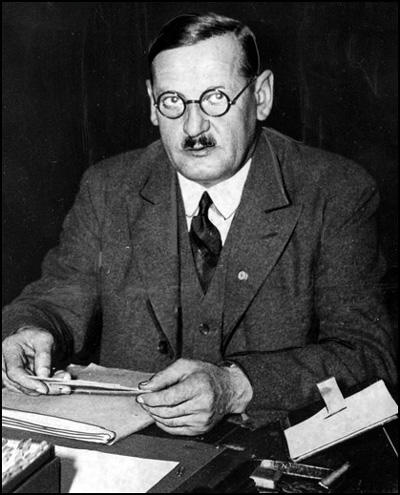

Anton Drexler

Anton Drexler was born in Munich, Germany on 13th June, 1884. Described as "bespectacled and unassuming" he was a locksmith and toolmaker who in 1902 moved to Berlin where he suffered periods of unemployment. Drexler was particularly humiliated by having to play a zither in a restaurant.

During the First World War he joined the right-wing nationalist group, the Fatherland Party. On 7th March 1918, Drexler set up a Committee of Independent Workmen. Drexler's idea was to form an organisation that would "combat the Marxism of the free trade unions" and to agitate for a "just" peace for Germany. His long-term objective was to create a party which would be both working class and nationalist. After six months it only had 40 members and in January 1919 decided to join with right-wing journalist, Karl Harrer, to form the German Worker's Party (GPW). Other early members included Gottfried Feder, Hermann Esser and Dietrich Eckart. Harrer was elected as chairman of the party.

On 30th May, 1919, Captain Karl Mayr, was appointed as head of the Education and Propaganda Department. He was given considerable funds to build up a team of agents and informants. On 12th September, Mayr sent Adolf Hitler to attend a meeting of the German Worker's Party (GWP). Hitler recorded in Mein Kampf (1925): "When I arrived that evening in the guest room of the former Sternecker Brau (Star Corner)... I found approximately 20–25 persons present, most of them belonging to the lower classes. The theme of Feder’s lecture was already familiar to me; for I had heard it in the lecture course... Therefore, I could concentrate my attention on studying the society itself. The impression it made upon me was neither good nor bad. I felt that here was just another one of these many new societies which were being formed at that time. In those days everybody felt called upon to found a new Party whenever he felt displeased with the course of events and had lost confidence in all the parties already existing. Thus it was that new associations sprouted up all round, to disappear just as quickly, without exercising any effect or making any noise whatsoever."

Hitler discovered that the party's political ideas were similar to his own. He approved of Drexler's German nationalism and anti-Semitism but was unimpressed with what he saw at the meeting. Hitler was just about to leave when a man in the audience began to question the logic of Feder's speech on Bavaria. Hitler joined in the discussion and made a passionate attack on the man who he described as the "professor". Drexler was impressed with Hitler and gave him a booklet encouraging him to join the GWP. Entitled, My Political Awakening, it described his objective of building a political party which would be based on the needs of the working-class but which, unlike the Social Democratic Party (SDP) or the German Communist Party (KPD) would be strongly nationalist.

Hitler commented: "In his (Feder's) little book he described how his mind had thrown off the shackles of the Marxist and trades-union phraseology, and that he had come back to the nationalist ideals. The pamphlet secured my attention the moment I began to read, and I read it with interest to the end. The process here described was similar to that which I had experienced in my own case ten years previously. Unconsciously my own experiences began to stir again in my mind. During that day my thoughts returned several times to what I had read; but I finally decided to give the matter no further attention."

Drexler had mixed feelings about Hitler but was impressed with his abilities as an orator and invited him to join the party. Adolf Hitler commented: "I didn't know whether to be angry or to laugh. I had no intention of joining a ready-made party, but wanted to found one of my own. What they asked of me was presumptuous and out of the question." However, Hitler was urged on by his commanding officer, Major Karl Mayr, to join. Hitler also discovered that Ernst Röhm, was also a member of the GWP. Röhm, like Mayr, had access to the army political fund and was able to transfer some of the money into the GWP. Drexler wrote to a friend: "An absurd little man has become member No. 7 of our Party."

Hitler gave his early impression of Drexler and Karl Harrer in Mein Kampf (1925): "Herr Drexler... was a simple worker, as speaker not very gifted, moreover no soldier. He had not served in the Army, and was not a soldier during the war, because his whole being was weak and uncertain, he was not a soldier during the war, and because his whole being was weak and uncertain, he was not a real leader for us. He (and Herr Harrer) were not cut out to be fanatical enough to carry the movement in their hearts, nor did he have the ability to use brutal means to overcome the opposition to a new idea inside the party. What was needed was one fleet as a greyhound, smooth as leather, and hard as Krupp steel."

Louis L. Snyder has argued that Drexler's political ideas were very important in developing his own philosophy: "Hitler was impressed with Drexler's ideas. He agreed wholeheartedly with the concept that there existed a diabolical Jewish-capitalistic-Masonic conspiracy which had to be counteracted. He believed that Drexler was right: on the one side there were the innocent German worker, farmer, and soldier; on the other there was the common enemy... the capitalistic Jews. From this germ came the essence of Hitler's Nazism."

The German Worker's Party used some of this money from Karl Mayr and Ernst Röhm to advertise their meetings. Hitler was often the main speaker and it was during this period that he developed the techniques that made him into such a persuasive orator. Hitler always arrived late which helped to develop tension and a sense of expectation. He took the stage, stood to attention and waited until there was complete silence before he started his speech. For the first few months Hitler appeared nervous and spoke haltingly. Slowly he would begin to relax and his style of delivery would change. He would start to rock from side to side and begin to gesticulate with his hands. His voice would get louder and become more passionate. Sweat poured of him, his face turned white, his eyes bulged and his voice cracked with emotion. He ranted and raved about the injustices done to Germany and played on his audience's emotions of hatred and envy. By the end of the speech the audience would be in a state of near hysteria and were willing to do whatever Hitler suggested. As soon as his speech finished Hitler would quickly leave the stage and disappear from view. Refusing to be photographed, Hitler's aim was to create an air of mystery about himself, hoping that it would encourage others to come and hear the man who was now being described as "the new Messiah".

In February 1920, the German Workers's Party published its first programme which became known as the "Twenty-Five Points". In the programme the party refused to accept the terms of the Versailles Treaty and called for the reunification of all German people. To reinforce their ideas on nationalism, equal rights were only to be given to German citizens. "Foreigners" and "aliens" would be denied these rights. To appeal to the working class and socialists, the programme included several measures that would redistribute income and war profits, profit-sharing in large industries, nationalization of trusts, increases in old-age pensions and free education. Gottfried Feder greatly influenced the anti-capitalist aspect of the Nazi programme and insisted on phrases such as the need to "break the interest slavery of international capitalism" and the claim that Germany had become the "slave of the international stock market".

Hitler's reputation as an orator grew and it soon became clear that he was the main reason why people were joining the party. At one meeting in Hofbräuhaus he attracted an audience of over 2,000 people and several hundred new members were enrolled. This gave Hitler tremendous power within the organization as they knew they could not afford to lose him. One change suggested by Hitler concerned adding "Socialist" to the name of the party. Hitler had always been hostile to socialist ideas, especially those that involved racial or sexual equality. However, socialism was a popular political philosophy in Germany after the First World War. This was reflected in the growth in the German Social Democrat Party (SDP), the largest political party in Germany. Hitler, therefore redefined socialism by placing the word "National" before it. He claimed he was only in favour of equality for those who had "German blood". Jews and other "aliens" would lose their rights of citizenship, and immigration of non-Germans should be brought to an end.

Adolf Hitler advocated that the party should change its name to the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). Hitler, therefore redefined socialism by placing the word "National" before it. He claimed he was only in favour of equality for those who had "German blood". Jews and other "aliens" would lose their rights of citizenship, and immigration of non-Germans should be brought to an end. In April 1920, the German Workers Party became the NSDAP. Hitler became chairman of the new party and Karl Harrer was given the honorary title, Reich Chairman.

Konrad Heiden, a journalist working in Munich, observed the way Hitler gained control of the party: "Success and money finally won for Hitler complete domination over the National Socialist Party. He had grown too powerful for the founders; they - Anton Drexler among them - wanted to limit him and press him to the wall. But it turned out that they were too late. He had the newspaper behind him, the backers, and the growing S.A. At a certain distance he had the Reichswehr behind him too. To break all resistance for good, he left the party for three days, and the trembling members obediently chose him as the first, unlimited chairman, for practical purposes responsible to no one, in place of Anton Drexler, the modest founder, who had to content himself with the post of honorary chairman (July 29, 1921). From that day on, Hitler was the leader of Munich's National Socialist Movement."

An early member of the NSDAP, Ernst Hanfstaengel, has argued that this brought an end to Drexler's influence on Hitler: "Anton Drexler, the original founder of the Party, was there most evenings, but by this time he was only its honorary president and had been pushed more or less to one side. A blacksmith by trade, he had a trade union background and although it was he who had thought up the original idea of appealing to the workers with a patriotic programme, he disapproved strongly of the street fighting and violence which was slowly becoming a factor in the Party's activities and wanted to build up as a working-class movement in an orderly fashion."

Drexler left the NSDAP in 1923. After the reorganization of the NSDAP in February, 1925, he became one of Hitler's opponents. Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) claims that the dispute was over long-term political objectives. "Hitler was as much interested in the working class and the lower middle class as Drexler, but he had no more sympathy for them than he had had in Vienna: he was interested in them as material for political manipulation. Their grievances and discontents were the raw stuff of politics, a means, but never an end. Hitler had agreed to the Socialist clauses of the programme, because in 1920 the German working class and the lower middle classes were saturated in a radical anti-capitalism; such phrases were essential for any politician who wanted to attract their support. But they remained phrases."

Anton Drexler died in Munich on 24th February, 1942.

Primary Sources

(1) Ernst Hanfstaengel first met Anton Drexler in 1922.

Anton Drexler, the original founder of the Party, was there most evenings, but by this time he was only its honorary president and had been pushed more or less to one side. A blacksmith by trade, he had a trade union background and although it was he who had thought up the original idea of appealing to the workers with a patriotic programme, he disapproved strongly of the street fighting and violence which was slowly becoming a factor in the Party's activities and wanted to build up as a working-class movement in an orderly fashion.

(2) Konrad Heiden, Der Führer – Hitler's Rise to Power (1944)

Success and money finally won for Hitler complete domination over the National Socialist Party. He had grown too powerful for the founders; they - Anton Drexler among them-wanted to limit him and press him to the wall. But it turned out that they were too late. He had the newspaper behind him, the backers, and the growing S.A. At a certain distance he had the Reichswehr behind him too. To break all resistance for good, he left the party for three days, and the trembling members obediently chose him as the first, unlimited chairman, for practical purposes responsible to no one, in place of Anton Drexler, the modest founder, who had to content himself with the post of honorary chairman (July 29, 1921). From that day on, Hitler was the leader of Munich's National Socialist Movement.

(3) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962)

The split between Hitler and the committee went deeper than personal antipathy and mistrust. Drexler and Harrer had always thought of the Party as a workers' and lower-middle-class party, radical and anti-capitalist as well as nationalist. These ideas were expressed in the programme, with its Twenty-five Points (drawn up by Drexler, Hitler, and Feder, and adopted in February 1920), as well as in the name of the German National Socialist Workers' Party. The programme was nationalist and anti-Semitic in character. All Germans (including those of Austria and the Sudetenland) were to be united in a Greater Germany. The treaties of Versailles and St Germain were to be abrogated. Jews were to be excluded from citizenship and office; those who had arrived since 1914 were to be expelled from Germany.

At the same time the Party programme came out strongly against Capitalism, the trusts, the big industrialists, and the big landowners. All unearned income was to be abolished; all war profits to be confiscated; the State was to take over all trusts and share in the profits of large industries; the big department stores were to be communalized and rented to small trades people, while preference in all public supplies was to be given to the small trader. With this went equally drastic proposals for agrarian reform: the expropriation without compensation of land needed for national purposes, the abolition of ground rents, and the prohibiting of land speculation.

There is no doubt that on Drexler's and Feder's part this represented a genuine programme to which they always adhered. Hitler saw it in a different light. Although for immediate tactical reasons in 1926 he was forced to declare the Party programme unalterable, all programmes to Hitler were means to an end, to be taken up or dropped as they were needed. "Any idea," he says in Mein Kampf, "may be a source of danger if it be looked upon as an end in itself." Hitler's own programme was much simpler: power, power for himself, for the Party, and the nation with which he identified himself. In 1920 the Twenty-five Points were useful, because they brought support; as soon as the Party had passed that stage, however, they became an embarrassment. Hitler was as much interested in the working class and the lower middle class as Drexler, but he had no more sympathy for them than he had had in Vienna: he was interested in them as material for political manipulation. Their grievances and discontents were the raw stuff of politics, a means, but never an end. Hitler had agreed to the Socialist clauses of the programme, because in 1920 the German working class and the lower middle classes were saturated in a radical anti-capitalism; such phrases were essential for any politician who wanted to attract their support. But they remained phrases.