On this day on 3rd February

On this day in 1399 John of Gaunt died. John of Gaunt, the fourth son of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault, was born at St Bavo's Abbey, Ghent, on 6th March 1340. He was brought up in the household of Edward, the Black Prince, and "was soon initiated into the strenuous military traditions of the Plantagenet family".

Gaunt was on his father's ship during the Anglo-Castilian sea battle off Winchelsea in August 1350 and was knighted at the start of the Norman campaign in July 1355. He also served with his father in Scotland in 1356.

The Black Prince arranged for John of Gaunt to marry Blanche of Lancaster, his third cousin, in 1359 (both were great-great-grandchildren of King Henry III). On the death of his father-in-law, Henry of Grosmont, the 1st Duke of Lancaster, in 1361, John received half his lands, the title "Earl of Lancaster", and distinction as the greatest landowner in the north of England.

At the age of twenty-two John of Gaunt was the richest nobleman in England - a status he was to retain throughout his life. The duchy of Lancaster estates yielded about £12,000 a year, an income at least double the amount enjoyed by any contemporary English magnate.

According to Jean Froissart Blanche was "young and pretty" and she gave birth to seven children, three of whom survived infancy: Philippa (1360), Elizabeth (1363) and Henry of Bolingbroke (1367). Blanche died on 12th September 1368, probably from the Black Death.

Edward III was in poor health and his son John of Gaunt became an important figure in the royal court. He was also sent on several diplomatic missions. In April 1367, his command of the English vanguard at Nájera increased his reputation as a military general. The Scottish Parliament even discussed the possibility of John of Gaunt succeeding the childless David II as king of Scotland.

On 21st September 1371, John of Gaunt married Constance of Castile, the daughter of Peter of Castile, the King of Castile, who died in 1369. Gaunt used the marriage to claim the crown of Castile. However, Henry of Castile, the illigetimate son of Alfonso XI, became the King of Castile. The duke was formally authorized to use the Castilian royal titles by Edward III on 30 January 1372. A plan to send an invasion force was cancelled in October 1372.

John's oldest brother, Edward, the Black Prince, had been the commander of the English army during the Hundred Years War, but suffering from repeated attacks of what was probably dysentery, he was forced to return to England. John of Gaunt, was now asked to replace him in France and in April 1373, his army of 6,000 men departed from Dover. "Stiff French resistance kept the English forces away from the Paris basin, however, and forced the duke to march eastwards, to Rheims and Troyes, and then southwards through the Auvergne to Aquitaine, which the duke and his army reached in December." John returned to England in April 1374.

In desperate need for money to fund the war, a Parliament was held in April 1376. John of Gaunt was the royal family's representative as both his father and elder brother were too ill to attend (his brother Edward died on 8th June). Members of the House of Commons complained about the heavy incidence of taxation and the consistent lack of military success. His support of John Wycliffe suggested that he was a religious reformer and this caused problems with church leaders.

February, 1377, Wycliffe was told to appear before Archbishop Simon Sudbury and charged with seditious preaching. Anne Hudson has argued: "Wycliffe's teaching at this point seems to have offended on three matters: that the pope's excommunication was invalid, and that any priest, if he had power, could pronounce release as well as the pope; that kings and lords cannot grant anything perpetually to the church, since the lay powers can deprive erring clerics of their temporalities; that temporal lords in need could legitimately remove the wealth of possessioners."

In 1377 the government introduced a poll-tax where four pence was to be taken from every man and woman over the age of fourteen. "This was a huge shock: taxation had never before been universal, and four pence was the equivalent of three days' labour to simple farmhands at the rates set in the Statute of Labourers". Edward III died soon afterwards and John of Gaunt took the blame for the new tax.

The leading magnates feared that John of Gaunt would claim the throne. They therefore promoted the idea, that his ten-year-old grandson, should become king. Richard II was crowned in July 1377. Thomas Walsingham described it as "a day of joy and gladness.... the long-awaited day of the renewal of peace and of the laws of the land, long exiled by the weakness of an aged king and the greed of his courtiers and servants."

In 1379 Richard II called a parliament to raise money to pay for the continuing war against the French. After much debate it was decided to impose another poll tax. This time it was to be a graduated tax, which meant that the richer you were, the more tax you paid. For example, the Duke of Lancaster and the Archbishop of Canterbury had to pay £6.13s.4d., the Bishop of London, 80 shillings, wealthy merchants, 20 shillings, but peasants were only charged 4d.

In 1380 John of Gaunt and his army was sent north to deal with problems on the northern border. The trouble began when pirates operating out of Hull and Newcastle. had captured a Scottish ship. The Scots reacted to the loss by breaching the border, terrorising the northern counties and looting Penrith. According to Dan Jones "protecting the northern border certainly held some private interest for him; but he was also a champion of the rights of the Crown - a trait that often saw him unfairly characterised as having personal ambitions to the throne."

While he was away, Simon Sudbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury, suggested a new poll tax of three groats (one shilling) per head over the age of fifteen. "There was a maximum payment of twenty shillings from men whose families and households numbered more than twenty, thus ensuring that the rich paid less than the poor. A shilling was a considerable sum for a working man, almost a week's wages. A family might include old persons past work and other dependents, and the head of the family became liable for one shilling on each of their 'polls'. This was basically a tax on the labouring classes."

The peasants felt it was unfair that they should pay the same as the rich. They also did not feel that the tax was offering them any benefits. For example, the English government seemed to be unable to protect people living on the south coast from French raiders. Most peasants at this time only had an income of about one groat per week. This was especially a problem for large families. For many, the only way they could pay the tax was by selling their possessions. John Wycliffe gave a sermon where he argued: "Lords do wrong to poor men by unreasonable taxes... and they perish from hunger and thirst and cold, and their children also. And in this manner the lords eat and drink poor men's flesh and blood."

John Ball toured Kent giving sermons attacking the poll tax. When the Archbishop of Canterbury, heard about this he gave orders that Ball should not be allowed to preach in church. Ball responded by giving talks on village greens. The Archbishop now gave instructions that all people found listening to Ball's sermons should be punished. When this failed to work, Ball was arrested and in April 1381 he was sent to Maidstone Prison. At his trial it was claimed that Ball told the court he would be "released by twenty thousand armed men".

In May 1381, Thomas Bampton, the Tax Commissioner for the Essex area, reported to the king that the people of Fobbing were refusing to pay their poll tax. It was decided to send a Chief Justice and a few soldiers to the village. It was thought that if a few of the ringleaders were executed the rest of the village would be frightened into paying the tax. However, when Chief Justice Sir Robert Belknap arrived, he was attacked by the villagers.

Belknap was forced to sign a document promising not to take any further part in the collection of the poll tax. According to the Anonimalle Chronicle of St Mary's: "The Commons rose against him and came before him to tell him... he was maliciously proposing to undo them... Accordingly they made him swear on the Bible that never again would he hold such sessions nor act as Justice in such inquests... And Sir Robert travelled home as quickly as possible."

After releasing the Chief Justice, some of the villagers looted and set fire to the home of John Sewale, the Sheriff of Essex. Tax collectors were executed and their heads were put on poles and paraded around the neighbouring villages. The people responsible sent out messages to the villages of Essex and Kent asking for their support in the fight against the poll tax.

Many peasants decided that it was time to support the ideas proposed by John Ball and his followers. It was not long before Wat Tyler, a former soldier in the Hundred Years War, emerged as the leader of the peasants. Tyler's first decision was to march to Maidstone to free John Ball from prison. "John Ball had been set free and was safe among the commons of Kent, and he was bursting to pour out the passionate words which had been bottled up for three months, words which were exactly what his audience wanted to hear."

Charles Poulsen, the author of The English Rebels (1984) has pointed out that it was very important for the peasants to be led by a religious figure: "For some twenty years he had wandered the country as a kind of Christian agitator, denouncing the rich and their exploitation of the poor, calling for social justice and freeman and a society based on fraternity and the equality of all people." John Ball was needed as their leader because alone of the rebels, he had access to the word of God. "John Ball quickly assumed his place as the theoretician of the rising and its spiritual father. Whatever the masses thought of the temporal Church, they all considered themselves to be good Catholics."

On 5th June there was a revolt at Dartford and two days later Rochester Castle was taken. The peasants arrived in Canterbury on 10th June. Here they took over the archbishop's palace, destroyed legal documents and released prisoners from the town's prison. More and more peasants decided to take action. Manor houses were broken into and documents were destroyed. These records included the villeins' names, the rent they paid and the services they carried out. What had originally started as a protest against the poll tax now became an attempt to destroy the feudal system.

The peasants decided to go to London to see Richard II. As the king was only fourteen-years-old, they blamed his advisers for the poll tax. The peasants hoped that once the king knew about their problems, he would do something to solve them. The rebels reached the outskirts of the city on 12 June. It has been estimated that approximately 30,000 peasants had marched to London. At Blackheath, John Ball gave one of his famous sermons on the need for "freedom and equality".

Wat Tyler also spoke to the rebels. He told them: "Remember, we come not as thieves and robbers. We come seeking social justice." Henry Knighton records: "The rebels returned to the New Temple which belonged to the prior of Clerkenwell... and tore up with their axes all the church books, charters and records discovered in the chests and burnt them... One of the criminals chose a fine piece of silver and hid it in his lap; when his fellows saw him carrying it, they threw him, together with his prize, into the fire, saying they were lovers of truth and justice, not robbers and thieves."

Charles Poulsen praises Wat Tyler as learning the "lessons of organisation and discipline" when in the army and in showing the "same pride in the customs and manners of his own class as the noblest baron would for his". The medieval historians were less complimentary and Thomas Walsingham described him as a "cunning man, endowed with much sense if he had applied his intelligence to good purposes".

John of Gaunt was still in Scotland with the English Army when these events took place. King Richard II sent a message to bring his soldiers, an estimated 20,000 men, back to London. However, the message did not arrive in time for him to take effective action. Dan Jones, the author of Summer of Blood: The Peasants' Revolt (2009), has pointed out: "Some four hundred miles from the worst crisis of order the country had ever known, the most experienced and powerful noble in the land was left exiled and impotent."

Richard II gave orders for the peasants to be locked out of London. However, some Londoners who sympathised with the peasants arranged for the city gates to be left open. Jean Froissart claims that some 40,000 to 50,000 citizens, about half of the city's inhabitants, were ready to welcome the "True Commons". When the rebels entered the city, the king and his advisers withdrew to the Tower of London. Many poor people living in London decided to join the rebellion. Together they began to destroy the property of the king's senior officials. They also freed the inmates of Marshalsea Prison.

Part of the English Army was at sea bound for Portugal whereas the rest were with John of Gaunt in Scotland. Thomas Walsingham tells us that the king was being protected in the Tower by "six hundred warlike men instructed in arms, brave men, and most experienced, and six hundred archers". Walsingham adds that they "all had so lost heart that you would have thought them more like dead men than living; the memory of their former vigour and glory was extinguished". Walsingham points out that they did not want to fight and suggests they may have been on the side of the peasants.

John Ball sent a message to Richard II stating that the rising was not against his authority as the people only wished only to deliver him and his kingdom from traitors. Ball also asked the king to meet with him at Blackheath. Archbishop Simon Sudbury and Robert Hales, the treasurer, both objects of the people's hatred, warned against meeting the "shoeless ruffians", whereas others, such as William de Montagu, the Earl of Salisbury, urged that the king played for time by pretending that he desired a negotiated agreement.

Richard II's biographer, Anthony Tuck, has pointed out: "Richard's own part in the discussions is almost impossible to determine, though some historians have suggested that he took the initiative in seeking to negotiate with the rebels, despite the fact that he was only fourteen when the rebellion occurred. Even before the Kentish rebels entered London, Richard had apparently suggested negotiation with their leaders at Greenwich, but the talks had broken down almost as soon as they began."

Richard II agreed to meet the rebels outside the town walls at Mile End on 14th June, 1381. Most of his soldiers remained behind. Charles Oman, the author of The Great Revolt of 1381 (1906), pointed the "ride to Mile End was perilous: at any moment the crowd might have broken loose, and the King and all his party might have perished... nevertheless, though surrounded all the way by a noisy and boisterous multitude, Richard and his party ultimately reached Mile End".

When the king met the rebels at 8.00 a.m. he asked them what they wanted. Wat Tyler explained the demands of the rebels. This includes the end of all feudal services, the freedom to buy and sell all goods, and a free pardon for all offences committed during the rebellion. Tyler also asked for a rent limit of 4d per acre and an end to feudal fines through the manor courts. Finally, he asked that no "man should be compelled to work except by employment under a regularly reviewed contract".

The king immediately granted these demands. Wat Tyler also claimed that the king's officers in charge of the poll tax were guilty of corruption and should be executed. The king replied that all people found guilty of corruption would be punished by law. The king agreed to these proposals and 30 clerks were instructed to write out charters giving peasants their freedom. After receiving their charters the vast majority of peasants went home.

G. R. Kesteven, the author of The Peasants' Revolt (1965), has pointed out that the king and his officials had no intention of carrying out the promises made at this meeting, they "were merely using those promises to disperse the rebels". However, Wat Tyler and John Ball were not convinced by the word given by the king and along with 30,000 of the rebels stayed in London.

While the king was in Mile End discussing an agreement with the king, another group of peasants marched to the Tower of London. There were about 600 soldiers defending the Tower but they decided not to fight the rebel army. Simon Sudbury (Archbishop of Canterbury), Robert Hales (King's Treasurer) and John Legge (Tax Commissioner), were taken from the Tower and executed. Their heads were then placed on poles and paraded through the streets of cheering Londoners.

Rodney Hilton argues that the rebels wanted revenge on all those involved in the levying of taxes or the administrating the legal system. Roger Leggett, one of the most important government lawyers was also killed. "They attacked not only the lawyers themselves - attorneys, pleaders, clerks of the courts - but others closely associated with the judicial processes... The hostility to lawyers and to legal records was not of course peculiar to the Londoners. The widespread destruction of manorial court records is well-known" during the rebellion.

The rebels also attacked foreign workers living in London. "The commons made proclamation that every one who could lay hands on Flemings or any other strangers of other nations might cut off their heads". It has been claimed that "some 150 or 160 unhappy foreigners were murdered in various places - thirty-five Flemings in one batch were dragged out of the church of St. Martin in the Vintry, and beheaded on the same block... The Lombards also suffered, and their houses yielded much valuable plunder."

It was agreed that another meeting should take place between Richard II and the leaders of the rebels at Smithfield on 15th June, 1381. William Walworth rode "over to the rebels and summoned Wat Tyler to meet the king, and mounted on a little pony, accompanied by only one attendant bearing the rebel banner, he obeyed". When he joined the king he put forward another list of demands that included: the removal of the lordship system, the distribution of the wealth of the church to the poor, a reduction in the number of bishops, and a guarantee that in future there would be no more villeins.

Richard II said he would do what he could. Wat Tyler was not satisfied by this reply. He called for a drink of water to rinse out his mouth. This was seen as extremely rude behaviour, especially as Tyler had not removed his hood when talking to the king. One of Richard's party shouted out that Tyler was "the greatest thief and robber in Kent". The author of the Anonimalle Chronicle of St Mary's claims: "For these words Wat wanted to strike the valet with his dagger, and would have killed him in the king's presence; but because he tried to do so, the Mayor of London, William of Walworth... arrested him... Wat stabbed the mayor with his dagger in the body in great anger. But, as it pleased God, the mayor was wearing armour and took no harm.. he struck back at the said Wat, giving him a deep cut in the neck, and then a great blow on the head. And during the scuffle a valet of the king's household drew his sword, and ran Wat two or three times through the body... Wat was carried by a group of the commons to the hospital for the poor near St Bartholomew's, and put to bed. The mayor went there and found him, and had him carried out to the middle of Smithfield, in the presence of his companions, and had him beheaded."

The peasants raised their weapons and for a moment it looked as though there was going to be fighting between the king's soldiers and the peasants. However, Richard rode over to them and said: "Will you shoot your king? I will be your chief and captain, you shall have from me that which you seek " He then spoke to them for some time and eventually they agreed to go back to their villages.

Chroniclers such as Henry Knighton and Thomas Walsingham suggested that these events were unplanned and unexpected. However, modern historians have doubts about this version of events. Anthony Tuck has argued: "The rapid arrival of the militia suggests some element of advance planning, and those around the king, even perhaps the king himself, may have intended to create an opportunity to kill or capture Tyler and separate him from the main body of his followers. If this is so, it was a risky strategy, as the Mile End meeting had been, and again Richard's personal courage is not in doubt."

An army, led by Thomas of Woodstock, John of Gaunt's younger brother, was sent into Essex to crush the rebels. A battle between the peasants and the King's army took place near the village of Billericay on 28th June. The king's army was experienced and well-armed and the peasants were easily defeated. It is believed that over 500 peasants were killed during the battle. The remaining rebels fled to Colchester, where they tried in vain to persuade the towns-people to support them. They then fled to Huntingdon but the towns people there chased them off to Ramsey Abbey where twenty-five were slain.

Richard II was not a very successful military commander. His biographer, Peter Earle, points out: "Richard, son of the Black Prince, inherited only his father's outward appearance and none of his skills at war. Not that he was the coward or weakling of legend - on many occasions in his reign he was to display outstanding courage - but his was the courage of pride, not military prowess." This was reflected in a failed military expedition to Scotland in 1385.

Richard's failure in Scotland encouraged the French to consider invading England. Charles VI assembled the largest force so far raised by either side during the Hundred Years War. This induced widespread panic and insecurity in England. Parliament met in October 1386, to consider the request from the chancellor, Michael de la Pole, for an unprecedented quadruple subsidy to cover the cost of defence against the threatened invasion. This was refused and the barons began to question the way Richard was ruling the country.

At first Parliament blamed Richard's advisors and his chancellor was impeached by the House of Commons on charges arising out of his conduct in office. De la Pole was found guilty and condemned to imprisonment, but Richard set aside the penalty and he retained his freedom. "Parliament then established a commission which was to hold office for a year and which was to conduct a thorough review of royal finances. It was to have control of the exchequer and the great and privy seals, and Richard was required to take an oath to abide by any ordinances it made."

Richard raised an army against Parliament. Led by Robert de Vere, Duke of Ireland it was said to contained no more than 4,000 men. Rumours began to circulate that Richard had agreed to accept military support from France, and that he would place England under French military occupation. Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, and several other nobles, including Henry of Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray, Earl of Nottingham, mobilized an army of their retainers numbering 4,500 and marched on de Vere's army. The king's army was defeated at the Battle of Radcot Bridge on 19th December 1387.

Richard was arrested and Woodstock threatened to have him executed because of his dealings with France. They eventually decided against it and instead forcing him to call a session of Parliament. Henry Knighton described it as the Merciless Parliament as it resulted in several of Richard's leading advisors, including Sir Nicholas Brembre, Simon de Burley and Robert Tresilian were executed. Alexander Neville, Archbishop of York, Robert de Vere and Michael de la Pole, all managed to escape to France where they died in exile.

On 3rd May 1389 Richard was allowed back on the throne. This time he made no attempt to revive the style of government which had brought about the crisis of 1387 and for the time being no new inner circle of courtiers emerged to enjoy Richard's favour and patronage. John of Gaunt returned to England in November 1389 and pledged his support to Richard. The atmosphere of peace was to last for six years. During this period he had some diplomatic success. This included a settlement in Ireland in 1394 and two years later negotiated a truce with France.

As soon as he felt strongly enough, Richard fought back against those who were responsible for ousting him from power in 1387. He ordered the arrest of Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, Richard FitzAlan, 11th Earl of Arundel and Thomas de Beauchamp, 12th Earl of Warwick. Gloucester was murdered soon afterwards and Arundel was executed on 21st September, 1397. Warwick made a full confession to attempting to overthrow the king, was banished for life to the Isle of Man.

John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, died on 3rd February 1399.

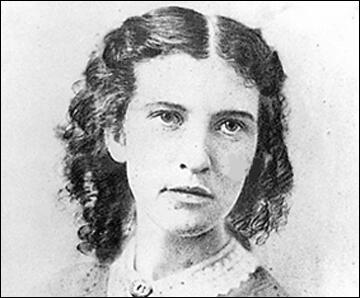

On this day in 1820 Susanna Inge was born in Folkestone. Her father Richard Inge Austin was a plumber, glazier and painter. A few years later the family moved to London and dropped the surname Austin.

Susanna later wrote: "You not know perhaps, that I never went to school but two months after I was nine years old - that at sixteen I could not write my own name - though I could read well, so I was told, and talk and spell correctly. The teaching I had while in Folkestone, where I had nearly all my schooling was good, and I was very forward, even for my age, being ahead of my cousins even those who were older than me. But writing was not taught in those days while children were so young, thus I knew nothing of writing and my parents were always talking of sending me to writing, but they never did."

In 1836 Susanna bought her a copy book and asked her to write to him. "This I did, though not often, for in those days postage was eight pence a letter and a sheet of paper a penny, so to me, who rarely had more than a penny or time a week to call my own, this was a small fortune and could not often be expended."

The 1841 census returns show that Susanna Inge had returned to Folkestone, where she was working as a family servant in the household of a linen draper in Broad Street. At this time she joined the the London Female Radical Association. When it was founded it stated it wanted to "unite with our sisters in the country, and to use our best endeavours to assist our brethren in obtaining universal suffrage". The organisation made the point that they would use their power as managers of the household to obtain the vote for their men by "to deal as much as possible with those shopkeepers who are favourable to the People's Charter".

Susanna Inge explained her decision in an article for The Northern Star in July, 1842. "As civilisation advances man becomes more inclined to place woman on an equality with himself, and though excluded from everything connected with public life, her condition is considerably improved". She went on to urge women to “assist those men who will, nay, who do, place women in on equality with themselves in gaining their rights, and yours will be gained also".

In October 1842, Susanna Inge and Mary Ann Walker attempted to establish a Female Chartist Association. Inge argued that in time women should be given the vote. However, she felt before this could happen women "ought to be better educated, and that, if she were, so far as mental capacity, she would in every respect be the equal of man”.

This plan to form a Female Chartist Association was criticised by some male Chartists. One declared that he "did not consider that nature intended women to partake of political rights". He argued that women were "more happy in the peacefulness and usefulness of the domestic hearth, than in coming forth in public and aspiring after political rights".

It was also suggested that if a "young gentleman" might try "to influence her vote through his sway over her affection". Mary Ann Walker responded by claiming that "she would treat with womanly scorn, as a contemptible scoundrel, the man who would dare to influence her vote by any undue and unworthy means; for if he were base enough to mislead her in one way, he would in another.”

On 6th November, 1842, The Sunday Observer reported that Susanna Inge was giving a lecture at the National Charter Hall in London. With her was another woman, Emma Matilda Miles. The newspaper suggested that the women had joined in response to the arrest and punishment of John Frost after the Newport Uprising. It would seem that Inge was a supporter of the Physical Force movement.

Susanna Inge was not content to be a mere propagandist. She had ideas on how Chartism might be better organised. In one letter to the The Northern Star she suggested that every Chartist locality should have its byelaws and plan of organisation hung in a prominent place, that these should be read before every meeting, and that any officer who failed to abide by them should be called to account.

Feargus O'Connor, the leader of the Physical Force chartists, was not in favour of women having equal political rights with men. He claimed that the role of the woman was to be a "housewife to prepare meals, to wash, to brew, and look after my comforts, and the education of my children." Anna Clark has pointed out that O'Connor demanded "entry into the public sphere for working men" and "the privileges of domesticity for their wives".

Susanna Inge wrote letters to O’Connor's newspaper complaining about his views. These were rejected for publication and in July, 1843, it admitted that Inge "very much questions the propriety or right of Mr O’Connor to name or suggest to the people, through the medium of the Northern Star, any person to fill any office whatever" as "it is not according to her ideas of democracy." The newspaper dismissed her comments with the words: "We dare say Miss Inge is greatly in love with her ideas of democracy; and so she ought, for we fancy they will suit nobody else”

She continued to be active in the Chartist movement and it was reported that Susanna Inge gave a lecture on the subject in August 1843. The Hereford Journal reported that she left the movement in February 1843, after a dispute with Mary Ann Walker. "Miss Susanna Inge, who had hitherto remained silent, now rose and tendered her resignation as secretary of the Female Chartist Association saying, with disdain, that she was quite sick of the business."

Susanna Inge continued to send letters and articles to the The Northern Star. In September, 1844, the editor commented "that even gallantry in Miss Inge’s case is not strong enough to break through" this censorship. She also tried to have her work published in other journals. George Reynolds, the editor of the Reynolds's Miscellany, sent back an article, advising her that she try a better class of magazine “for which its style was more suited”. Another rejection letter suggested "it is very good… it shows you have power to do, but that you require study. This is a proof of what you can do; rather than anything done… This is good but you can do better".

On 18th February 1847, aged 27, she gave birth to a son who she named James. Susanna was unmarried and now took the name Susanna McGregor. In the 1851 census she referred to herself as a widow and was living at 10 Dorrington Street, Clerkenwell. Susanna was recorded as working as a "furrier finisher".

In 1857 Susanna MacGregor and her son emigrated to New York City, settling in Brooklyn, where she found work in the fur trade. She kept in touch with the family of her younger brother John, sending letters, stories and poems to her nieces Alice and Jessie. Attempts to have her work published in American magazines ended in failure.

Susanna Inge MacGregor died on 26th December 1902.

On this day in 1821 Elizabeth Blackwell was born in Bristol, England. Her father, Samuel Blackwell, held progressive views and Elizabeth and her sisters were taught subjects such as Latin, Greek and mathematics.

In 1832 the Blackwell family emigrated to the United States. Samuel Blackwell was strongly opposed to slavery and after meeting William Lloyd Garrison, became involved in Abolitionist activities. When her husband died in 1838 Hannah Blackwell had nine children to look after. Elizabeth contributed to the family income by opening a small private school with two of her sisters, Anna and Marian, in Cincinnati. Later she taught in Kentucky and North Carolina.

Elizabeth became interested in the topic of medicine. At that time there were no women doctors in the United States but Elizabeth argued that many women would prefer to consult with a woman rather than a man about her health problems. She was rejected by 29 medical schools before being accepted by Geneva Medical School in 1847. The male students ostracized her and teachers refused permission for her to attend medical demonstrations. Despite these problems, when graduated in 1849 she was ranked first in her class. She also became the first woman to qualify as a doctor in the United States and over 20,000 people turned up to watch Blackwell being awarded her MD.

Elizabeth now moved to Europe where she took a midwives' course at La Maternite in Paris. While in France she contracted purulent ophthalma from a baby she was treating. As a result of this infection she lost the sight of one eye. Elizabeth now had to abandon her plans to become a surgeon.

In October, 1850, Elizabeth moved to England where she worked under Dr. James Paget at St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London. It was here that she met and became friends with Florence Nightingale and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. Both these women were inspired by Elizabeth's success and became pioneers in women's medicine in Britain.

Elizabeth returned to the United States in 1851 and attempted to find work in New York. Refused posts in the city's hospitals and dispensaries, she was forced to work privately. Her experiences of gender discrimination encouraged her to write the book The Laws of Life (1852).

In 1853 Elizabeth opened a dispensary in the slums of New York. Soon afterwards she was joined by her younger sister, Emily Blackwell, who had now also graduated with a medical degree, and Marie Zakrzewska. In 1857 the three women established the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. The women gave public lectures on hygiene, created a health centre, appointed sanitary visitors and campaigned for better preventive medicine

During the American Civil War Elizabeth organized the Women's Central Association of Relief. This involved the selection and training of nurses for service in the war. Blackwell, along with Emily Blackwell and Mary Livermore, played an important role in the development of the United States Sanitary Commission.

After the war the Blackwell sisters established the Women's Medical College in New York. Elizabeth became professor of hygiene until 1869 when he moved to London to help form the National Health Society and the London School of Medicine for Women. After meeting Charles Kingsley Blackwell became active in the Christian Socialist movement.

In 1875 Elizabeth Garrett Anderson invited Blackwell to became professor of gynecology at the London School of Medicine for Children. She remained in this post until she had a serious fall in 1907.

Elizabeth Blackwell died in Hastings, Sussex, on 31st May, 1910.

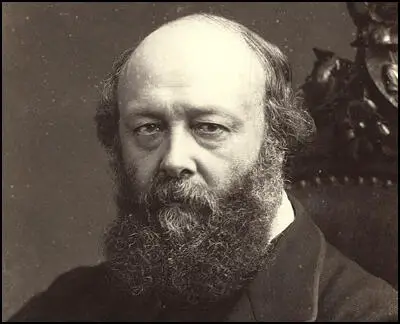

On this day in 1830 Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, was born. Robert Cecil, son of the 2nd Marquis of Salisbury, was born at Hatfield House in 1830. Cecil was educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford.

A supporter of the Conservative Party Cecil was elected to represent Stamford in 1853. He was granted the title of Lord Cranborne on the death of his brother in 1865. Cranborne played an important role in the defeat of the Parliamentary Reform Bill proposed by William Gladstone in 1866.

After Gladstone was forced to resign from office, the new prime minister, Lord Derby, appointed Cranborne as his Secretary for India. He strongly opposed the proposal by Benjamin Disraeli to introduce his own parliamentary reform bill. When he realised he was unable to stop Disraeli's 1867 Reform Act he resigned from the cabinet. He later argued: "Unfortunately for Conservatism, its leaders belong solely to one class; they are a clique composed of members of the aristocracy, land-owners, and adherents whose chief merit is subserviency. The party chiefs live in an atmosphere in which a sense of their own importance and of the importance of their class interests and privileges is exaggerated, and to which the opinions of the common people can scarcely penetrate."

In 1868 Robert Cecil succeeded his father as the 3rd Marquis of Salisbury. In 1874 Salisbury returned to government as Benjamin Disraeli's Secretary for India. Four years later he replaced Lord Derby as Foreign Secretary.

On the death of Benjamin Disraeli in 1878 the Marquis of Salisbury became leader of the Conservative Party. However, he had to wait until the general election of 1885 before he became Prime Minister. He argued in a letter to Randolph Churchill that he found government difficult: "We have to give some satisfaction to both the upper classes and the masses. This is especially difficult with the upper classes - because all legislation is rather unwelcome to them, as tending to disturb a state of things with which they are satisfied. It is evident, therefore, that we must work at less speed and at a lower temperature than our opponents. Our bills must be tentative and cautious, not sweeping and dramatic."

He was replaced by William Gladstone briefly in 1886 but also headed the Conservative governments between 1886-92 and 1895-1902. Salisbury supported the policies that led to the Boer War (1899-1902).

Robert Cecil, the Marquis of Salisbury, retired from public life in July 1902 and died the following year on 22nd August, 1903.

On this day in 1831 Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, proposed parliamentary reform bill. In June 1830 Earl Grey made an impressive speech on the need for parliamentary reform. The Duke of Wellington, the prime minister and leader of the Tories in Parliament, replied that the "existing system of representation was as near perfection as possible". It was now clear that the Tories would be unwilling to change the electoral system and that if people wanted reform they had to give their support to the Whigs.

On 15th November, 1830 Wellington's government was defeated in a vote in the House of Commons. The new king, William IV, was more sympathetic to reform than his predecessor and decided to ask Earl Grey to form a government. As soon as Grey became prime minister he formed a cabinet committee to produce a plan for parliamentary reform. Details of the proposals were announced on 3rd February 1831. The bill was passed by the House of Commons by a majority of 136, but despite a powerful speech by Earl Grey, the bill was defeated in the House of Lords by forty-one.

The defeat of the Reform Act resulted in Earl Grey calling a general election. The Whigs were popular with the electorate and after the election they had a larger majority than before in the House of Commons. A second reform bill was also defeated in the House of Lords. When people heard the news, riots took place in several British towns. Nottingham Castle was burnt down and in Bristol the Mansion House was set on fire.

In 1832 Earl Grey tried again but the House of Lords refused to pass the bill. Grey now appealed to William IV for help. He agreed to Grey's request to create a large number of new Whig peers. When the Lords heard the news, they agreed to pass the Reform Act. On 7th June the Bill received the Royal Assent and large crowds celebrated in the streets of Britain.

Earl Grey now called another general election and in the new reformed House of Commons, Grey had a majority of over a hundred. The Whigs were now able to introduce and pass a series of reforming measures. This included an act for the abolition of slavery in the colonies and the 1833 Factory Act. After the passing of the 1834 Poor Law Earl Grey decided to resign from office.

On this day in 1874 Gertrude Stein was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania. As a child she lived in Vienna and Paris before returning to the United States to study at Radcliffe College (1893-97) and Johns Hopkins Medical School (1897-1901) but left before taking her degree. In 1903 Stein moved to France where she lived with her lover, Alice B. Toklas. Her home became a gathering place for European artists and American writers.

Her first novel, Three Lives, was published in 1909. Its prose style is highly unconventional and virtually dispenses with normal punctuation. Tender Buttons (1914) was even more experimental and sold extremely badly. Other work by Stein include her theory of writing, Composition and Explanation (1926), The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), two volumes of memoirs, Everybody's Autobiography (1937) and Wars I Have Seen (1945), Brewsie and Willie (1946) a novel about the Second World War and an opera about Susan B. Anthony, the women's rights campaigner, The Mother of Us All (1946). Gertrude Stein died at Neuilly-sur-Seine on 27th July, 1946.

On this day in 1892 Juan Negrín, the son of a wealthy businessman, was born in Spain in 1892. He studied at several German universities and in 1923 he became professor of physiology at the Medical Faculty of Madrid University.

In 1929 Negrin joined he Socialist Party (PSOE) and two years later was elected to the Cortes. Over the next few years he was a supporter of Indalecio Prieto, the leader of the moderate faction in the PSOE.

Negrin supported the Popular Front government and in September 1936 Francisco Largo Caballero appointed him minister of finance. During the Spanish Civil War Negrin took the controversial decision to transfer the Spanish gold reserves to the Soviet Union in return for arms to continue the war. Worth $500 million at the time, critics argued that this action put the Republican government under the control of Joseph Stalin.

In the Civil War the National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT), the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) and the Worker's Party (POUM) played an important role in running Barcelona. This brought them into conflict with other left-wing groups in the city including the Union General de Trabajadores (UGT), the Catalan Socialist Party (PSUC) and the Communist Party (PCE).

On the 3rd May 1937, Rodriguez Salas, the Chief of Police, ordered the Civil Guard and the Assault Guard to take over the Telephone Exchange, which had been operated by the CNT since the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. Members of the CNT in the Telephone Exchange were armed and refused to give up the building. Members of the CNT, FAI and POUM became convinced that this was the start of an attack on them by the UGT, PSUC and the PCE and that night barricades were built all over the city.

Fighting broke out on the 4th May. Later that day the anarchist ministers, Federica Montseny and Juan Garcia Oliver, arrived in Barcelona and attempted to negotiate a ceasefire. When this proved to be unsuccessful, Negrin now called on Francisco Largo Caballero to use government troops to takeover the city. Largo Caballero also came under pressure from Luis Companys, the leader of the PSUC, not to take this action, fearing that this would breach Catalan autonomy.

On 6th May death squads assassinated a number of prominent anarchists in their homes. The following day over 6,000 Assault Guards arrived from Valencia and gradually took control of Barcelona. It is estimated that about 400 people were killed during what became known as the May Riots.

These events in Barcelona severely damaged the Popular Front government. Negrin was highly critical of the way Francisco Largo Caballero handled the May Riots. President Manuel Azaña agreed and on 17th May he asked Negrin to form a new government. Negrin was now a communist sympathizer and from this date Joseph Stalin obtained more control over the policies of the Republican government.

In April 1938 Negrin also took over the Ministry of Defence. He now began appointing members of the Communist Party (PCE) to important military and civilian posts. This included Marcelino Fernandez, a communist, to head the Carabineros. Communists were also given control of propaganda, finance and foreign affairs. The socialist, Luis Araquistain, described Negrin's government as the "most cynical and despotic in Spanish history."

Juan Negrín now attempted to gain the support of western governments by announcing his plan to decollectivize industries. On 1st May 1938 Negrin published a thirteen-point program that included the promise of full civil and political rights and freedom of religion. President Manuel Azaña attempted to oust Negrin in August 1938. However, he no longer had the power he once had and with the support of the communists in the government and armed forces, Negrin was able to survive.

On 27th February, 1939, the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain recognized the Nationalist government headed by General Francisco Franco. Later that day President Azaña resigned from office, declaring that the war was lost and that he did not want Spaniards to make anymore useless sacrifices.On 27th February, 1939, the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain recognized the Nationalist government headed by General Francisco Franco. Later that day Manuel Azaña resigned from office, declaring that the war was lost and that he did not want Spaniards to make anymore useless sacrifices.

Negrin now promoted communist leaders such as Antonio Cordon, Juan Modesto and Enrique Lister to senior posts in the army. Segismundo Casado, commander of the Republican Army of the Centre, now became convinced that Negrin was planning a communist coup. On 4th March, Casedo, with the support of the socialist leader, Julián Besteiro and disillusioned anarchist leaders, established an Anti-Negrin National Defence Junta.

On 6th March José Miaja in Madrid joined the rebellion by ordering the arrests of Communists in the city. Negrin, about to leave for France, ordered Luis Barceló, commander of the First Corps of the Army of the Centre, to try and regain control of the capital. His troops entered Madrid and there was fierce fighting for several days in the city. Anarchists troops led by Cipriano Mera, managed to defeat the First Corps and Barceló was captured and executed.

Negrin now fled to France where he attempted to maintain a government in exile. After the invasion of the German Army in the summer of 1940 he went to live in England.

After the Second World War Negrin returned to France where he died on 12th November, 1956.

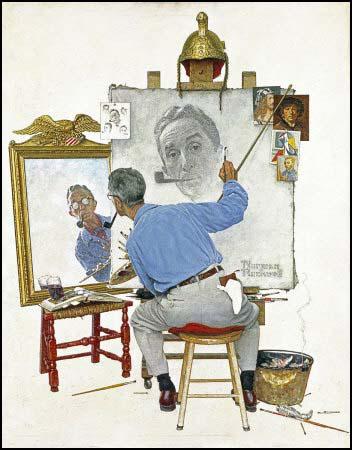

On this day in 1894 artist Norman Rockwell was born in New York City. According to his biographer, Karal Ann Marling: "The young Norman was skinny and clumsy at sports. He feared the rough neighbourhoods near his family's home on the Upper West Side. Coddled by his mother, Nancy, who boasted of her English heritage and artistic forbears, he also came to resent her imaginary illnesses and spates of religious fervor."

Norman's father, Waring Rockwell, worked in the textile industry. He was also an amateur artist and spent time with his son copying illustrations out of magazines. Waring also read to his family the novels of Charles Dickens. While he read, Norman drew the characters from the novels. According to one art critic: "His (Norman Rockwell) strong sense of narrative and his eye for the telling detail were byproducts of those long, nurturing evenings in his father's company." During this period his artistic heroes were Charles Dana Gibson, Harrison Fisher, Howard Pyle and Newell Convers Wyeth.

In 1907 the family moved to Mamaroneck, a small settlement on the Long Island Sound. Rockwell went to the local school but travelled the 25 miles to Manhatten to study at the the New York School of Art, an institution run by the artist, William Merritt Chase. In 1909, at the age of 15, he left high school and enrolled in the National Academy School.

Rockwell found the teaching at the academy very conventional and in 1910 he joined the Art Students League. With teachers such as Thomas Eakins, Robert Henri, John Sloan, Art Young, George Luks, Boardman Robinson, George Bellows, Howard Pyle and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, it developed a reputation for progressive teaching methods and radical politics. At this time it had nearly a thousand students and was considered the most important art school in the country.

His main teacher was Thomas Fogarty. He later claimed that Fogarty's main contribution to his career was that he taught him the importance of meeting deadlines and following his client's wishes. Fogarty was impressed with Rockwell's talent that in 1913 he arranged for him to be appointed art editor of Boys' Life, the journal of the Boy Scouts of America.

Rockwell really wanted to work for the Saturday Evening Post and in March 1916 he visited its main office in Philadelphia. He showed the editor, George Horace Lorimer, a collection of front cover ideas. Lorimer was so impressed with the work that he purchased two cover pictures and commissioned three more. This was the start of his long-term relationship with the magazine that was to last over 45 years.

The author of Norman Rockwell (2005) has argued: "The pictorial cover was crucial to the success of a magazine. It had to make itself visible and comprehensible at a distance, so the casual passerby would want to pluck that issue off the rack at the newsstand. It had to identify the Saturday Evening Post and carry with it some slight hint of the character of the journal... In a sense, it also needed to mirror the taste and status of the potential reader, who could see him - or herself in that image. Covers were a tricky business, and one crucial to the success of the Saturday Evening Post."

Rockwell's first Saturday Evening Post cover appeared on 20th May, 1916. Boy with Baby Carriage shows a little boy, dressed in his Sunday best, pushing a baby in a pram past two other boys in baseball uniforms who mock him for the "unmanly" task he is performing. At this time, the covers were only printed in two colours, and Rockwell makes good use of the red and back on the white paper.

Rockwell used one boy, Billy Paine, to pose for all three characters. Rockwell used hats, haircuts, and facial expressions to disguise this fact. Rockwell later recalled: "At the beginning of the modeling sessions I'd set a stack of nickels on a table beside my easel. Every 25 minutes... I'd transfer of the nickels to the other side of the table, saying, Now that's your pile."

Later that year, Rockwell married Irene O'Connor, a local schoolteacher. The couple moved to New Rochelle where he takes over a studio that was formerly owned by Frederick Remington. By this time he was in great demand as an illustrator and provided a large number of covers for Saturday Evening Post and The Literary Digest. Rockwell was also recruited to produce illustrations for advertising that appeared in magazines and on posters.

Soon after the United States entered the First World War, Rockwell joined the US Navy. Over the next year Rockwell worked for US Navy publications. After the Armistice Rockwell returned to full-time illustrating. As well as magazine work, Rockwell became involved in designing advertising campaigns. As Karal Ann Marling has pointed out: "The big money of the era was in advertising art. Foodstuffs had been one of the first customer products to be branded... In the 1920s, a new, modern wave of edibles hit the mass market, with a corresponding demand for artwork to sell chewing gum, soft drinks, and candy."

One of Rockwell's most popular paintings, No Swimming, appeared on the front cover of the Saturday Evening Post on 4th June, 1921. The art critic, Christopher Finch, has argued: "We find that it has been painted in an almost impressionistic way. There is no question hem of an outline having been drawn then filled in with color. On the contrary, the image is built up from areas of boldly applied pigment - a well-loaded brush is evident - overlapping and overlaying each other to build up planes that create the illusion of solidity and depth. (Note in particular the way in which the anatomy of the boy in the foreground has been evoked.) Many of the edges of forms have been deliberately blurred in this picture, partly to help produce a sense of speed, but largely as a natural consequence of this approach to image-making. Even Rockwell's highly stylized signature is loosely painted."

In 1930 Rockwell went to Hollywood to paint the film-star Gary Cooper for the Saturday Evening Post. This was used to advertise Cooper's latest film, The Texan. As the author of Norman Rockwell (2005) has pointed out: "His time in Hollywood had important artistic consequences: Rockwell was becoming a master of theatrical and cinematic effects. His covers and occasional illustrations took on the appearance of moments from the movies, when the actors face the camera directly, when directors compose their scenes to under-score key moments in the script, when overstated costuming allows the audience to identify the genre at a glance. Rockwell's trip to Hollywood in 1930 cemented the connection between his art and the art of the filmmaker."

Rockwell divorced Irene in 1930. Soon afterwards he met Mary Barstow, another young school-teacher and later that year they got married. Over the next few years she gave birth to three sons: Jerry (1932), Tommy (1933) and Peter (1936).

Rockwell was a supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal. However, he was unable to express his political views in his covers for the Saturday Evening Post. He therefore had to rely on subtle methods to get his views across. For example, his cover, The Ticket Seller, that appeared on 24th April, 1937, shows a man selling tickets to holiday destinations, while trapped like a circus lion within his own cage.

In 1939 Rockwell and his family moved to Arlington, Vermont. On the outbreak of the Second World War, Rockwell offered his services free of charge to the United States Office of War Information (OWI) in Washington. He was rejected by the person in charge of pictorial propaganda with the words: "The last war you illustrators did the posters. This war we're going to use fine arts men, real artists."

Rockwell refused to be beaten and began thinking about he could help. He was eventually inspired by a joint statement made by Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill about the reasons why it was important to fight a war against Nazi Germany. In his autobiography, he points out that after returning from a town meeting: "My gosh, I thought, that's it. There it is. Freedom of Speech. I'll illustrate the Four Freedoms using my Vermont neighbors as models. I'll express the ideas in simple, everyday scenes. Freedom of Speech - a New England town meeting. Freedom from Want - a Thanksgiving dinner."

The Freedom of Speech painting showed Jim Edgerton, who had argued for the building of a new high school in Arlington. Edgerton had found no support for his views. But the meeting had listened respectfully to his views. Norman Rockwell considered this was a good example of freedom of speech in action.

Rockwell found coming up with an idea for a painting on religion much more difficult. After making several false starts he painted a close-up portrait of seven individuals of various skin tones, united in prayer. Freedom to Worship included the words in golden letters at the top of the canvas: "Each according to the dictates of his own conscience."

Freedom from Want depicted his own family. The Rockwell cook, Mrs. Wheaton, is shown presenting the turkey. His wife, Mary Rockwell, can be seen on the left side of the table. His mother is the elderly lady seated across from her. Rockwell later recalled: "She (Mrs. Wheaton) cooked it, I painted it, and we ate it. That was one of the few times I've ever eaten the model."

The final painting, Freedom from Fear, was produced during the Blitz. It shows the husband and wife watching their two children asleep. The man carries a newspaper, with a headline referring to the bombing of London. His biographer, Karal Ann Marling, argues that: "The rag doll abandoned on the floor just behind his feet echoes the posture of the sleeping children but, in her limp, discarded form, also alludes to the European children who did not enjoy the safety of a warm bed guarded by caring parents."

When the editor of the Saturday Evening Post saw these four paintings he decided to publish them inside the magazine so that they would be suitable for framing. These were so popular that the United States Office of War Information printed 2,500,000 posters of the paintings. The original paintings went out on tour.

Another popular cover produced during the Second World War was Rosie the Riveter (29th May, 1943). The term Rosie the Riveter had been first used in a song of the same name written by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb in 1942. The song portrays Rosie as an assembly line worker, who is filling the role of man who had joined the armed forces. By the time Rockwell painted the picture Rosie had become a feminist icon.

Norman Rockwell also produced humorous covers for the Saturday Evening Post during the war. A good example of this is Tattoo Artist that appeared on 4th March, 1944. In the painting the tattoos is in the process of crossing out the names of girls already displayed on the arm of the sailor. The work makes fun of sailors who had the reputation of having a different girlfriend at every port.

The art critic, Ken Johnson, has argued: "It is no secret that Rockwell relied on photographs to achieve the seeming naturalism of his paintings. But the extent and sophistication of his use of photography from the late 1930s on will come as a surprise to many of his fans and detractors. Rockwell did not shoot his pictures, but employed professional photographers, including Gene Pelham, Bill Scovill, Louis J. Lamone and others who remain unidentified. But Rockwell did orchestrate every other aspect of studio sessions. He found and bought props; recruited friends, acquaintances and relatives as models; constructed sets; and conceived scenes like a Hollywood movie director."

After the war Rockwell was probably the best known artist in the United States. Christopher Finch has pointed out: "We should not judge Rockwell by individual work, nor even by a selection of his finest pictures, but rather by the cumulative effect of his total output. It is this that makes Rockwell so outstanding a figure in the pantheon of American popular culture. Elsewhere I have remarked that it seems, at first glance, almost absurd to talk of Norman Rockwell as having a distinctive style - his stock in trade is quasi-photographic realism, and his technique derives from a variety of conventional academic sources - yet a Rockwell painting is immediately recognizable as a Rockwell painting. Clearly he does have a style that is unlike any other. It is not easy to define. however, because it dots not depend upon any broad mannerisms. It is, rather, made up of small but significant deviations from the photographic and academic norms."

In 1947 Norman Rockwell helped to establish the Famous Artists School in Westport, Connecticut. The organisation, headed by Albert Dorne, ran corresponding courses. Faculty members that included Rockwell, Austin Briggs, Stevan Dohanos, Robert Fawcett, Peter Helck, Fred Ludekens, Al Parker, Ben Stahl, Harold von Schmidt and Jon Whitcomb, produced step-by-step textbooks on how to produce art work for magazine covers and illustrations for advertising campaigns.

Rockwell's wife, Mary, suffered from alcoholism and a variety of other health problems. She was treated at the Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. In 1953 Norman Rockwell moved to the town to be close to his wife and to receive treatment for depression. In 1959 Mary died unexpectedly of heart failure.

Rockwell also had strong political views. He felt particularly strongly over the issue of civil rights. Ken Stuart, the art director of the Saturday Evening Post, began turning down his front covers. On other occasions, he had section of a cover painting repainted without telling the artist that he had done so. Rockwell threatened to stop working for the magazine, but the editor, Ben Hibbs, promised it would not happen again.

On 13th February, 1960, the magazine's front-cover was Triple Self-Portrait. The Saturday Evening Post acknowledged his importance to the magazine by publishing a serial version of autobiography that year. This was later released as a book, My Adventures as an Illustrator. Rockwell was a great supporter of John F. Kennedy and his last illustration for the magazine was a portrait of the assassinated president on 14th December, 1963.

The death of Kennedy convinced him to join Look Magazine, as a commentator of current affairs. Rockwell's first double-page illustration for the magazine, The Problem We All Live With (14th January, 1964) was one of his most memorable paintings. It shows Ruby Bridges, who in 1960, when she was 6 years old, became involved in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) campaign to integrate the New Orleans School system. When she entered William Frantz Elementary School in 1960 she became the first African-American child to attend an all-white elementary school in the South.

Rockwell also painted Southern Justice, that dealt with the deaths of three Congress on Racial Equality field-workers in Meridian, Mississippi, Michael Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman, on 21st June, 1964. The painting appeared in Look Magazine on 29th June, 1965. The magazine also published several of his paintings that reflected his opposition to the Vietnam War.

Karal Ann Marling has argued: "Some Americans turned a blind eye to Rockwell's pleas for racial justice and idealism, however. In the summer of 1964, three so-called Freedom Riders James Chancy, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman were killed for their efforts to register black voters in the South. Eventually, their bodies were discovered in an earthen dam in rural Philadelphia, Mississippi. Rockwell responded in Look in June of 1965 with an imaginative recreation of their martyrdom. In the harsh glare of headlights, the shadows of armed Klansmen draw closer to the bleeding figure of Chancy, in the arms of one of his white companions. The painting argues for the brotherhood of the trio and presents their attackers as inhuman creatures of the night. The landscape is an almost Biblical scene of desolation: bare, rock-strewn, and forbidding -a killing ground. It is Norman Rockwell's most passionate indictment to date of the nation whose little missteps and personal follies had been his lifelong preoccupation. The second great issue of the decade was the spreading conflict in Indochina. By the end of 1965, 150,000 American troops were fighting in Vietnam and opposition to the war was growing. In a work originally painted for the Congress of Racial Equality, Rockwell shows slaughter as the great equalizer of America's blacks and whites. The two young men who lie side by side in death have become Blood Brothers. In at least one of the preliminary sketches for the work, they wear the uniforms of U. S. Marines."

Norman Rockwell died at his home in Stockbridge on 8th November, 1978.

On this day in 1909 French philosopher, Simone Weil, the daughter of a doctor, was born in Paris, France, in 1909. A member of a prosperous Jewish family Weil studied at the Lycée Fénelon (1920-24), Lycée Victor Duruy (1924-25) and Lycée Hebri IV (1925-28) before entering the Ecole Normale Supérieure in 1928.

At university Weil developed radical political views and was known as the 'Red Virgin'. After graduating she taught at schools in Le Puy, Auxeterre, Roanne, Bourges and Saint-Quentin. Weil also worked as a factory worker for Renault in order to discover what it was like to be a member of the working class. She also served as a volunteer with the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War.

During the Second World War the Weil family left Paris and went to live in Marseilles before moving to the United States. Weil moved to London in November 1942, where he joined General D and his government in exile. She wanted to return to the front-line but because of her poor health she worked for the minister of the interior preparing for the postwar social reconstruction of France.

Simone Weil died of a combination of tuberculosis and anorexia on 24th August 1943. Her writings published after her death included Gravity and Grace (1952) and The Need for Roots (1952).

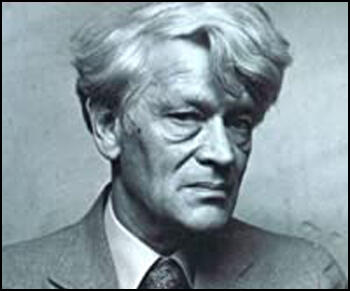

On this day in 1924 E. P. Thompson, the son of Methodist missionaries, was born in Oxford. He studied history at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. His studies were interrupted by the Second World War and as a member of the British Army saw action in Italy. His brother, Frank Thompson, was killed while fighting for the Bulgarian partisans.

In 1948 Thompson became lecturer in history at the University of Leeds. For the next 17 years he worked as a extra mural lecturer. Later he became Reader in the Centre for the Study of Social History at the University of Warwick.

Thompson joined Eric Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, A. L. Morton, Raphael Samuel, George Rudé, John Saville, Dorothy Thompson, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan and Maurice Dobb in forming the Communist Party Historians' Group. In 1952 members of the group founded the journal, Past and Present. Over the next few years the journal pioneered the study of working-class history.

John Saville later wrote: "The Historian's Group had a considerable long-term influence upon most of its members. It was an interesting moment in time, this coming together of such a lively assembly of young intellectuals, and their influence upon the analysis of certain periods and subjects of British history was to be far-reaching."

Disillusioned by the events in the Soviet Union and the invasion of Hungary, Thompson, like many Marxist historians, left the Communist Party in 1956. Later he became active in the Labour Party.

In 1957 Thompson helped form the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). Other members included J. B. Priestley, Bertrand Russell, Fenner Brockway, Frank Allaun, Donald Soper, Vera Brittain, Sydney Silverman, James Cameron, Jennie Lee, Victor Gollancz, Konni Zilliacus, Richard Acland, A. J. P. Taylor, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot.

Thompson wrote William Morris, Romantic to Revolutionary (1955) and The Making of the English Working Class (1963). In protest against the "tailoring of Warwick University to the needs of industry" Thompson resigned his post in 1971.

Thompson spent the next few years as a roving ambassador for world peace. He also wrote a series of books including Whigs and Hunters (1975), The Poverty of Theory (1978), Writing by Candlelight (1980), Protest and Survive (1980),Customs in Common (1992), Witness Against the Beast (1994) and Making History: Writings on History and Culture (1994). Edward Thompson died on 28th August, 1993.

On this day in 1952 Harold L. Ickes died. Ickes was born in Frankstown, Pennsylvania on 15th March, 1874. He attended the University of Chicago and after graduating in 1897 he set himself up as a lawyer. Ickes held progressive political views and often worked for causes he believed in without pay.

As a young man he was deeply influenced by the politics of John Altgeld. He later wrote: "How the Chicago Tribune and others had smeared this humane and courageous man because he had fought for the underdog, and especially because he had pardoned those who still lived of the innocent victims who had been railroaded to the penitentiary after the Haymarket riot! So far as I could see, Altgeld stood about where I wanted to stand on social questions."

Ickes worked for Theodore Roosevelt in the 1912 presidential election. After the demise of the Progressive Party, Ickes switched to Hiram Johnson and managed his unsuccessful campaign to became a presidential candidate in 1924.

Harold L. Ickes became a follower of Franklin D. Roosevelt after being impressed by his progressive policies as governor of New York. In 1932 Ickes played an important role in persuading progressive Republicans to support Roosevelt in the presidential election. He was a supporter of the New Deal. As he later argued: "Many billions of dollars could properly be spent in the United States on permanent improvements. Such spending would not only help us out of the depression, it would do much for the health, well-being and prosperity of the people. I refuse to believe that providing an adequate water supply for a municipality or putting in a sewage system is a wasteful expenditure of money. Any money spent in such fashion as to make our people healthier and happier human beings is not only a good social investment, it is sound from a strictly financial point of view. I can think of no better investment, for instance, than money paid out to provide education and to safeguard the health of the people."

In 1933 Roosevelt appointed Ickes as his Secretary of the Interior. This involved running the Public Works Administration (PWA) and over the next six years spent more than $5,000,000,000 on various large-scale projects. Ickes, a strong supporter of civil rights, he worked closely with Walter Francis White of the NAACP to establish quotas for African American workers in PWA projects.

His work was praised by the New York Times: "Mr. Ickes knows all the rackets that infest the construction industry. He is a terror to collective bidders and skimping contractors. He warns that the PWA fund is a sacred trust fund and that only traitors would graft on a project undertaken to save people from hunger. He insists on fidelity to specifications; cancels violated contracts mercilessly, sends inspectors to see that men in their eagerness to work are not robbed of pay by the kickback swindle."

Ickes felt that others in the administration, such as Harry L. Hopkins, had more power and influence over Roosevelt's decision. Ickes did not get on with Harry S. Truman and resigned from his government in 1946 in protest over the appointment of Edwin W. Pauley, Under Secretary of the Navy.

In his final years Ickes wrote a syndicated newspaper column and contributed regularly to the New Republic. Ickes wrote several books including New Democracy (1934), Back to Work: The Story of the PWA (1935), Yellowstone National Park (1937), The Third Term Bugaboo: A Cheerful Anthology (1940), Fighting Oil: The History and Politics of Oil (1943) and The Autobiography of a Curmudgeon (1943).

Harold L. Ickes died in Washington on 3rd February, 1952. The Secret Diary of Harold L. Ickes, was published posthumously in 1953.