Patricia Woodlock

Mary Winifred Patricia Woodlock, the first of four children of Marion Teresa Martin Woodlock (1847-1913) and David Woodlock (1842-1929) was born in Liverpool on 25th October 1873. At the time her father was an assistant in a drapery shop. In his spare time, he studied at St George's Museum, Walkley, which had been founded by John Ruskin for the education of local workers. (1)

After leaving school Patricia Woodlock worked as an apprentice to a female confectioner and was living at 92 Division Street, Sheffield. (2) She later returned home and lived with her parents at 46 Nicander Road, Sefton Park, Liverpool. David Woodlock now described himself as an "Artist" (3) He was also a socialist and a member of the Independent Labour Party and encouraged his daughter to be involved in politics. (4)

In 1903 Woodlock joined the Liverpool branch of the Women Social & Political Union. In an article in Votes for Women she explained why she felt so strongly about the subject: "A member of Parliament recently spoke of members of the WSPU as being possessed by fanaticism, and it occurred to her that politicians stood in need of a new dictionary – so many words having a different meaning as applied to women or to men – this word fanaticism simply meant enthusiasm." (5)

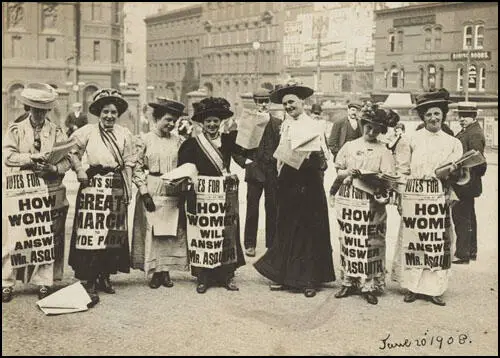

Patricia Woodlock in Manchester

In March 1907 Woodlock came to London to take part in the Woman's Parliament at Caxton Hall. She was arrested in Parliament Square and as this was her third offence she was sent to prison for a month. When she left prison she was described along with Emma Sproson as being "the most unruly and turbulent of spirits". (6) Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence argued that Woodlock was "'the heart of our Movement... the centre, the pivot upon which every part of it turns." (7)

Patricia Woodlock (far right) selling Votes for Women in Manchester on 20th June, 1908.

Patricia Woodlock and Mabel Capper organized a series of public demonstrations at Manchester parks in favour of women's suffrage. The demonstration held at Heaton Park on 19th July 1908, was attended by an estimated 50,000 people. The Manchester Evening News described the demonstration as "decorous", "informative" and "logical". (8)

and Mary Leigh at Batley (1907)

Members of the WSPU had given out leaflets promoting the meeting in Manchester city centre the previous day. Speakers included Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst. Patricia Woodlock and Mabel Capper decided to try making a speech on women's suffrage in the Manchester Royal Exchange. According to Carole O'Reilly: "The Royal Exchange, this bastion of male enterprise was entered by Capper and Woodcock where they attempted to make a speech about women's suffrage but were asked to leave the Exchange or be arrested." (9)

WSPU Organiser in Liverpool

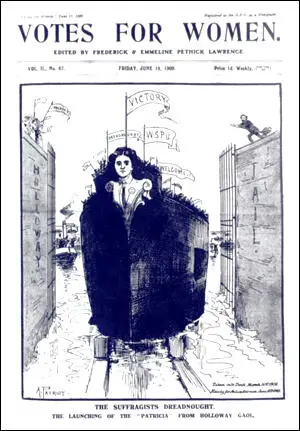

In 1909 Woodlock was appointed as organiser of Liverpool WSPU. (10) In March Woodlock was one of the Liverpool delegates to the Second Women's Parliament in Caxton Hall, London. Woodlock was arrested along with Dora Marsden, and was sentenced to three months in prison because she was as a persistent offender. (11) At the time it was the longest sentence given to a member of the WSPU. (12) Christabel Pankhurst described Woodlock as "one of those who are the great strength of the women's movement, for she is fearless, loyal and unselfish, ready to do the smallest or greatest service, as a speaker and above all as a fighter." (13)

In the House of Commons MPs complained about the length of the sentence. Herbert Gladstone, the Home Secretary stated that considering her previous behaviour the sentence was justified: "This lady, who had three times previously been committed for the same class of offence, and who intimated that if released she would straightway do the same thing, was only required to give securities for good behaviour, and can therefore come out of prison at any time on complying with the order of the Court. I see no reason for interference on my part." (14)

Votes for Women published a profile of Woodlock while she was in prison: "But we who know her know that Patricia Woodlock will never be broken. She has not once faltered or looked back since she heard the call for womanhood of the world more than three years ago. It was in December 1905, that she tried with other Lancashire women to enter the House that is supposed to represent the people of Great Britain. She was sent to Holloway for two weeks, which entailed spending her Christmas in prison. A few weeks later, in February 1907, she again formed one of the deputations of fifty-nine women, and rather than give a pledge that was against her conscience, she suffered a month in Holloway. If the authorities thought this would quell her spirit they were entirely wrong, for in March of the same year, after only a few days of the freedom that those who have been in prison can alone appreciate at its full value, she tried again to put the woman's demand for enfranchisement before the Prime Minister and was sent to prison for one month without the option of a fine. Miss Woodlock has done unceasing and enthusiastic work for the movement in Liverpool and elsewhere, her devotion winning her the love and respect of all with whom she came into contact, and bringing to her own heart the happiness that results from a complete abnegation of self for the sake of humanity." (15)

While she was in prison she was visited by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. Patricia's father, David Woodlock, sent her a letter of thanks and pointed out that he fully supported his daughter's actions: "I am very sure that anything that I can put on paper will but inadequately express my feeling towards you and your thoughtfulness on this occasion and throughout the whole time of my daughter's connection with the movement. I was especially touched (who would not be?) at the fine demonstration of comradeship and greatness of heart displayed by you when, on the morning of your own release from prison, your first public utterance – bold, courageous, and in every way worthy of you – was of sympathy and comfort for the one who still remained behind. Rest assured you will not be disappointed in her. I know my daughter well, and her feeling towards the cause she has at heart, especially the two fine souls she has always looked up to as the ensign and embodiment of that cause, Mrs Pankhurst and yourself; and I think I can safely say that you will always find her ready, loyal, and courageous. 'Britons never shall be slaves'. Indeed! Not much likelihood while we have these young heroines as examples of the prospective mothers of the race!" (16)

On her release on 16th June, Woodlock was greeted by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and several hundred supporters: "As early as half-past seven a large crowd assembled opposite the prison gates, augmented from time to time by the curious or sympathetic among the passers-by, and time went on the numbers swelled, until several hundreds were waiting, the enlivening strains of Bryer's band and the vigorous efforts of bill-distributors making the time pass quickly. As the hour of release drew near a hush fell on the assembled crowd, and when the gate opened and a solitary figure emerged, a mighty cheer went up. Miss Woodlock, who looked pale and thin, but had the light of indomitable courage burning in her eyes, at once entered Mrs Pethick Lawrence's motor-car, which was in waiting, and was driven away, the crowd following, cheering and singing the Marseillaise. It was inspiriting to see the numbers of strangers – principally girls and working men – joining in the song and waving aloft their tool-bags and dinner-bundles."

Woodlock was taken to the Inns of Court where Emmeline Pankhurst gave a speech acknowledging her commitment to the cause: "Mrs Pankhurst... said, no woman had deserved more highly than this brave pioneer in the cause of woman's freedom… During the time she had been a member of the Union, Patricia Woodlock had over and over again taken a front place in the fighting line, and had proved her devotion to the cause by being five times arrested and four times imprisoned… Patricia Woodlock, whose courage in sustaining prison treatment had fired then with enthusiasm."

Mary Gawthorpe also addressed the meeting: "The women of the country honoured Patricia Woodlock because they loved and honoured the case so much, and because to every woman there always came a day when she realised how infinitely more great the cause itself was than any personal sacrifice that might be made for it." Woodlock replied that it "was the object of the Government in sending women to prison in this so-called century of progress. She supposed that the object of men in political power was to stop women for agitating, but they did not know women, and the more they sent them to prison the more determined the women were when they came out.... When women were determination to have their rights, they would get them. They were not asking for favours because they were women; all they wanted was equality as subject." (17)

Bingley Hall Protest

On 22nd September 1909 Patricia Woodlock, Mary Leigh, Charlotte Marsh, Laura Ainsworth, Mabel Capper and Rona Robinson conducted a rooftop protest at Bingley Hall, Birmingham, where Herbert Asquith was addressing a meeting from which all women had been excluded. Using an axe, Leigh removed slates from the roof and threw them at the police below. Sylvia Pankhurst later recalled: "No sooner was this effected, however, than the rattling of missiles was heard on the other side of the hall, and on the roof of the house, thirty feet above the street, lit up by a tall electric standard was seen the little agile figure of Mary Leigh, with a tall fair girl (Charlotte Marsh) beside her. Both of them were tearing up the slates with axes, and flinging them onto the roof of the Bingley Hall and down into the road below-always, however, taking care to hit no one and sounding a warning before throwing. The police cried to them to stop and angry stewards came rushing out of the hall to second this demand, but the women calmly went on with their work." (18)

The Freeman's Journal reported: "Mary Leigh and Mabel Capper have long been among the most reckless members of the suffragist movement. They were two of a large band who visited Birmingham in September, 1909, and were arrested with others on charge arising out of a desperate and well-organised attempt to storm Bingley Hall where Mr Asquith was speaking to an audience of ten thousand. Leigh and another, eluding the vigilance of the police, climbed on to the roof of an adjoining factory, from which she threw ginger beer bottles, slates, and other missiles on the glass roof of Bingley Hall, and into the street when the Premier was passing in a motor car. While awaiting his appearance the women amused themselves by throwing projectiles at the crowd in the street and the police, several officers being struck. A policeman who climbed on the roof – a hazardous undertaking – found Leigh with her boots off, jumping about like a cat, as he described it, and armed with an axe used for the purpose of ripping slates from the roof: 'Come on up at your peril,' the women shouted to the officers, who were struck several times before effecting an arrest." (19)

Leigh got four months's imprisonment, Marsh three months, Woodlock a month and others got fourteen days. They immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the three women by force. (20)

In November 1909, after release, Patricia Woodlock and Laura Ainsworth approached the prison doctor, Dr. Ernest Helby, in the street. He had force-fed Woodlock and others and the two women demanded the immediate release of fellow suffragette Charlotte Marsh. Later that day Dr. Helby's windows were found to be smashed, but no legal action was taken. Marsh was eventually released on 9th december. she had been fed by stomach tube a total of 139 times. (21)

Black Friday

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. However, when Keir Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party, requested two hours to discuss the Conciliation Bill, H. H. Asquith made it clear that he intended to shelve it. (22)

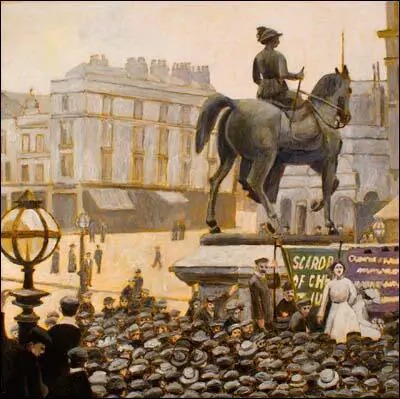

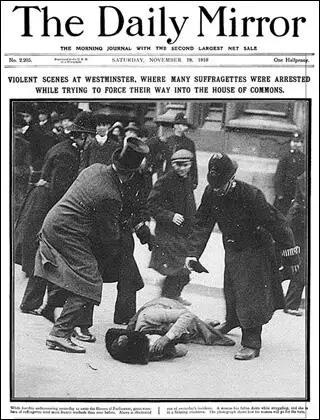

Emmeline Pankhurst was furious at what she saw as Asquith's betrayal and on 18th November, 1910, arranged to lead 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. Pankhurst and a small group of WSPU members, were allowed into the building but Asquith refused to see them. Women, in "detachments of twelve" marched forward but were attacked by the police. (23)

Votes for Women reported that 159 women and three men were arrested during this demonstration that became known as "Black Friday". (24) This included Patricia Woodlock, Ada Wright , Catherine Marshall, Eveline Haverfield, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Mary Leigh, Vera Holme, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Kitty Marion, Clara Giveen, Eileen Casey, Lilian Dove-Wilcox and Grace Roe. (25)

Sylvia Pankhurst later described what happened: "As, one after the other, small deputations of twelve women appeared in sight they were set upon by the police and hurled aside. Mrs Cobden Sanderson, who had been in the first deputation, was rudely seized and pressed against the wall by the police, who held her there by both arms for a considerable time, sneering and jeering at her meanwhile.... Just as this had been done, I saw Miss Ada Wright close to the entrance. Several police seized her, lifted her from the ground and flung her back into the crowd. A moment afterwards she appeared again, and I saw her running as fast as she could towards the House of Commons. A policeman struck her with all his force and she fell to the ground. For a moment there was a group of struggling men round the place where she lay, then she rose up, only to be flung down again immediately. Then a tall, grey-headed man with a silk hat was seen fighting to protect her; but three or four police seized hold of him and bundled him away. Then again, I saw Miss Ada Wright's tall, grey-clad figure, but over and over again she was flung to the ground, how often I cannot say. It was a painful and degrading sight. At last, she was lying against the wall of the House of Lords, close to the Strangers' Entrance, and a number of women, with pale and distressed faces were kneeling down round her. She was in a state of collapse." (26)

Several women reported that the police dragged women down the side streets. "We knew this always meant greater ill-usage.... The police snatched the flags, tore them to shreds, and smashed the sticks, struck the women with fists and knees, knocked them down, some even kicked them, then dragged them up, carried them a few paces and flung them into the crowd of sightseers." It was claimed that two women, Cecilia Haig and Henria Williams, died because of the beatings they endured that day. "I saw Celilia Haig go out with the rest; a tall, strongly built, reserved woman, comfortably situated, who in ordinary circumstances might have gone through life without receiving an insult, much less a blow. She was assaulted with violence and indecency, and died in December 1911, after a painful illness, arising from her injuries. Henria Williams, already suffering from a weak heart, did not recover from the treatment she received that night in the Square, and died on January 1st." (27)

The photograph of Ada Wright on the front page of The Daily Mirror the next day caused a great deal of embarrassment to the Home Office and the government demanded that the negative be destroyed. (28) Wright told a reporter that she had been at seven suffragette demonstrations, but had "never known the police so violent." (29) Charles Mansell-Moullin, who had helped treat the wounded claimed that the police had used "organised bands of well-dressed roughs who charged backwards and forwards through the deputations like a football team without any attempt being made to stop them by the police." (30)

Sylvia Pankhurst believed that Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary, had encouraged this show of force. "Never, in all the attempts which we have made to carry our deputations to the Prime Minister, have I seen so much bravery on the part of the women and so much violent brutality on the part of the policeman in uniform and some men in plain clothes. It was at the same time a gallant and a heart-breaking sight to see those little deputations battling against overwhelming odds, and then to see them torn asunder and scattered, bruised and battered, against the organized gangs of rowdies. Happily, there were many true-hearted men in the crowd who tried to help the women, and who raised their hats and cheered them as they fought. I found out during the evening that the picked men of the A Division, who had always hitherto been called out on such occasions, were this time only on duty close to the House of Commons and at the police station, and that those with whom the women chiefly came into contact had been especially brought in from the outlying districts. During our conflicts with the A Division they had gradually come to know us, and to understand our aims and objects, and for that reason, whilst obeying their orders, they came to treat the women, as far as possible, with courtesy and consideration. But these men with whom we had to deal on Friday were ignorant and ill-mannered, and of an entirely different type. They had nothing of the correct official manner, and were to be seen laughing and jeering at the women whom they maltreated." (31)

Churchill had been a long-term opponent of votes for women. As a young man he argued: "I shall unswervingly oppose this ridiculous movement (to give women the vote)... Once you give votes to the vast numbers of women who form the majority of the community, all power passes to their hands." His wife, Clementine Churchill, was a supporter of votes for women and after marriage he did become more sympathetic but was not convinced that women needed the vote. When a reference was made at a dinner party to the action of certain suffragettes in chaining themselves to railings and swearing to stay there until they got the vote, Churchill's reply was: "I might as well chain myself to St Thomas's Hospital and say I would not move till I had had a baby." However, it was the policy of the Liberal Party to give women the vote and so he could not express these opinions in public. (32)

Henry Brailsford was commissioned to write a report on the way that the police dealt with the demonstration. He took testimony from a large number of women, including Mary Frances Earl: "In the struggle the police were most brutal and indecent. They deliberately tore my undergarments, using the most foul language - such language as I could not repeat. They seized me by the hair and forced me up the steps on my knees, refusing to allow me to regain my footing... The police, I understand, were brought specially from Whitechapel." (33)

Paul Foot, the author of The Vote (2005) has pointed out, Brailsford and his committee obtained "enough irrefutable testimony not just of brutality by the police but also of indecent assault - now becoming a common practice among police officers - to shock many newspaper editors, and the report was published widely". (34) However, Edward Henry, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, claimed that the sexual assaults were committed by members of the public: "Amongst this crowd were many undesirable and reckless persons quite capable of indulging in gross conduct." (35)

Later Life

Black Friday was the last militant action took for the WSPU. She had been imprisoned seven times over a three year period. At the time of the 1911 Census, Patricia Woodlock (36) was living with her parents, David (67), Marion (63) and her sister and brother: Evangeline (26) and Charles (24) at 46 Nicander Road, Sefton Park, Liverpool. (36)

In 1919 and 1920, Patricia Woodlock was living with her father, David Woodlock, her married sister and brother-in-law (Mrs Evangeline Smith and Edward Smith) in Greenbank Road, West Toxteth, Liverpool. In 1938 - 1939 Patricia Woodlock was living with her married sister Mrs Evangeline Smith at 6 Victoria Park, Wavertree, Liverpool. (37)

Patricia Woodlock, aged 87, died in Wandsworth in 1961.

Primary Sources

(1) Votes for Women (11th June 1909)

"She is a Liverpool girl, refined, tender-hearted, heroic", wrote a journalist in the Liverpool Courier of Patricia Woodcock, who is to be released next Wednesday, after serving a sentence of three months imprisonment in the second division. She has had a plank bed, poor and wretchedly served food, prison dress, and worst of all, solitary confinement for twenty-two or twenty-three hours every day for seventy-seven days, even exercising and attending chapel quite alone. "It is like taking a bludgeon to break a butterfly" says the same writer.

But we who know her know that Patricia Woodlock will never be broken. She has not once faltered or looked back since she heard the call for womanhood of the world more than three years ago. It was in December 1905, that she tried with other Lancashire women to enter the House that is supposed to represent the people of Great Britain. She was sent to Holloway for two weeks, which entailed spending her Christmas in prison. A few weeks later, in February 1907, she again formed one of the deputations of fifty-nine women, and rather than give a pledge that was against her conscience, she suffered a month in Holloway. If the authorities thought this would quell her spirit they were entirely wrong, for in March of the same year, after only a few days of the freedom that those who have been in prison can alone appreciate at its full value, she tried again to put the woman's demand for enfranchisement before the Prime Minister and was sent to prison for one month without the option of a fine.

Miss Woodlock has done unceasing and enthusiastic work for the movement in Liverpool and elsewhere, her devotion winning her the love and respect of all with whom she came into contact, and bringing to her own heart the happiness that results from a complete abnegation of self for the sake of humanity.

(2) Votes for Women (18th June, 1909)

Wednesday, June 16, was a notable day in the annals of the WSPU, for on that morning was welcomed back to freedom Patricia Woodlock, after three months' imprisonment in Holloway. As early as half-past seven a large crowd assembled opposite the prison gates, augmented from time to time by the curious or sympathetic among the passers-by, and t time went on the numbers swelled, until several hundreds were waiting, the enlivening strains of Bryer's band and the vigorous efforts of bill-distributors making the time pass quickly.

As the hour of release drew near a hush fell on the assembled crowd, and when the gate opened and a solitary figure emerged, a mighty cheer went up. Miss Woodlock, who looked pale and thin, but had the light of indomitable courage burning in her eyes, at once entered Mrs Pethick Lawrence's motor-car, which was in waiting, and was driven away, the crowd following, cheering and singing the "Marseillaise". It was inspiriting to see the numbers of strangers – principally girls and working men – joining in the song and waving aloft their tool-bags and dinner-bundles. At 9.15 a large party assembled at breakfast at the Inns of Court Hotel to give Miss Woodlock an official welcome…

Mrs Pankhurst then, amid great applause, presented Miss Woodlock with the illuminated address and Holloway broach, given to every prisoner on release, and she also pinned on her breast a special medal "For Valour", which, as she said, no woman had deserved more highly than this brave pioneer in the cause of woman's freedom…

During the time she had been a member of the Union, Patricia Woodlock had over and over again taken a front place in the fighting line, and had proved her devotion to the cause by being five times arrested and four times imprisoned…

Many women would not have volunteered for the deputation on June 29 but for the example of Patricia Woodlock, whose courage in sustaining prison treatment had fired then with enthusiasm. Miss Pankhurst's own determination to make that deputation was, she added, very largely due to the way in which Patricia Woodlock had gone through solitary confinement.

Miss Woodlock then spoke. She said she had been wondering ever since she had been leading the enforced "simple life" in Holloway what was the object of the Government in sending women to prison in this so-called century of progress. She supposed that the object of men in political power was to stop women for agitating, but they did not know women, and the more they sent them to prison the more determined the women were when they came out. A member of Parliament recently spoke of members of the WSPU as being possessed by fanaticism, and it occurred to her that politicians stood in need of a new dictionary – so many words having a different meaning as applied to women or to men – this word fanaticism simply meant enthusiasm. When women were determination to have their rights, they would get them. They were not asking for favours because they were women; all they wanted was equality as subjects….

Miss Mary Gawthorpe announced the arrangements to give Miss Woodlock a public welcome in Lancashire, and said that Patricia Woodlock was the very first to volunteer to go to the Lancashire deputation would be an even greater success, the greatest that has ever been achieved… The women of the country honoured Patricia Woodlock because they loved and honoured the case so much, and because to every woman there always came a day when she realised how infinitely more great the cause itself was than any personal sacrifice that might be made for it.

(3) David Woodlock, letter to Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence (June, 1909)

I am very sure that anything that I can put on paper will but inadequately express my feeling towards you and your thoughtfulness on this occasion and throughout the whole time of my daughter's connection with the movement. I was especially touched (who would not be?) at the fine demonstration of comradeship and greatness of heart displayed by you when, on the morning of your own release from prison, your first public utterance – bold, courageous, and in every way worthy of you – was of sympathy and comfort for the one who still remained behind. Rest assured you will not be disappointed in her. I know my daughter well, and her feeling towards the cause she has at heart, especially the two fine souls she has always looked up to as the ensign and embodiment of that cause, Mrs Pankhurst and yourself; and I think I can safely say that you will always find her ready, loyal, and courageous. "Britons never shall be slaves". Indeed! Not much likelihood while we have these young heroines as examples of the prospective mothers of the race!

(4) J. G. Swift MacNeill, asking a question of Herbert Gladstone, Home Secretary (26 April 1909)

J. G. Swift MacNeill asked the Secretary of State for the Home Department whether he is aware that Miss Patricia Woodcock, a member of a women's suffrage deputation appointed by the National Women's Social and Political Union, was arrested and charged with assaulting the police, and sentenced on 31st March, at Bow Street, to three months' imprisonment in the second division, in default of finding securities; and whether, having regard to the fact that if Miss Woodcock earns the remission to which good conduct entitles her she must, under the terms of the sentence, remain in prison until 16th June, he will consider the advisability of taking steps for the shortening of this term of imprisonment inflicted on a political offender and accompanied with incidents of personal indignity to which public opinion is adverse?

Herbert Gladstone: This lady, who had three times previously been committed for the same class of offence, and who intimated that if released she would straightway do the same thing, was only required to give securities for good behaviour, and can therefore come out of prison at any time on complying with the order of the Court. I see no reason for interference on my part.

(5) David Simkin, Family History Research (18th June, 2020)

David Woodlock was born on 10th or 11th October 1842 in Ballyporeen, County Tipperary, Ireland, the son of Margaret Hennessy and John Joseph Woodlock (1800-1890), an Irish ‘coal dealer'.

David Woodcock came to England at the age of 12 and by 1861 he was living in Liverpool and working as an assistant in a drapery shop. Ten years later, David Woodlock was still working in the drapery trade in Liverpool. (At the time of the 1871 Census Woodlock is described as a 29 year old "Drapery Shopman". The 1871 census return records David Woodlock residing at 28 Almond Road, Liverpool, living with his father, 70 year old John Woodlock, and his two siblings, twenty-year old Margaret Woodlock and his younger brother, Thomas Woodlock , who was also employed in a draper's shop.

On 16th November 1871, at St Brigid's Catholic Church, Liverpool, David Woodlock married Marion Teresa Martin (born 1847, Liverpool, Lancs.). This union produced four children:

1. Mary Winifred Patricia Woodlock was born on 25th October 1873, the first of four children born to Marion Teresa Martin (1847-1913) and David Woodlock (1842-1929). When their daughter was baptised at St Anne's Catholic Church, Liverpool on 9th November 1873, her Christian names were recorded in the baptismal register as "Mary Winifred". No mention is made of her middle name of ‘Patricia', the forename by which she is generally known today.

2. David Sarsfield Woodlock born in Liverpool on 3rd October 1875 - died 1965, Calgary, Alberta, Canada,

3. Evangeline Woodlock born in Liverpool in 1884. Married Edward Smith in 1912.

4. Charles Stuart Woodlock born in Sale, Cheshire, on 10th October 1887. Later became a Jesuit Priest

By 1891, Winifred Patricia Woodlock was working as an apprentice to a female confectioner in Sheffield. The 1891 Census records Winifred Woodlock as a 17 year old "Apprentice Confectioner" at 92 Division Street, Sheffield.

During the late 1880s, Woodlock was living in Sheffield with his wife and four children, and working as a ‘hosier and haberdasher'. In his spare time, he studied at St George's Museum, Walkley, which had been founded by John Ruskin for the education of local workers.

At the time of the 1911 Census, David Woodlock and his family were residing at 46 Nicander Road, Sefton Park, Liverpool. David Woodlock, aged 67, describes himself as " Painter ( Artist )". No occupation is given for his wife Marion (63) or his three grown-up children – Winifred Patricia Woodlock (36), Evangeline (26) or Charles Stuart Woodlock (24). [David Sarsfield Woodlock had emigrated to North America in 1910. David Woodlock junior later settled in Alberta, Canada].

In 1919 and 1920, Patricia Woodlock was living with her father, David Woodlock, her married sister and brother-in-law (Mrs Evangeline Smith and Edward Smith) in Greenbank Road, West Toxteth, Liverpool.

In 1938 - 1939 Patricia Woodlock was living with her married sister Mrs Evangeline Smith at 6 Victoria Park, Wavertree, Liverpool.

The death of (Winifred) Patricia Woodlock, aged 87, was registered in Wandsworth, South London, during the 2nd Quarter of 1961.