On this day on 6th August

On this day 1862 Elizabeth Robins, the first child of Charles Ephraim Robins (1832–1893) and Hannah Maria Crow (1836–1901), was born in Louisville, Kentucky. Elizabeth's mother, an opera singer, was committed to an insane asylum when she was a child. Her father was an insurance broker and banker. He was also a follower of Robert Owen and held progressive political views. Robins sent Elizabeth to Vassar College to study medicine but at eighteen she ran away to become an actress.

In 1885, Elizabeth Robins married the actor, George Richmond Parks. Whereas Elizabeth was in great demand, George struggled to get parts. On 31st May 1887, he wrote Elizabeth a note saying that "I will not stand in your light any longer" and signed it "Yours in death". That night he committed suicide by jumped into the Charles River wearing a suit of theatrical armour.

In 1888 Elizabeth travelled to London where she introduced British audiences to the work of Henrik Ibsen. Elizabeth produced and acted in several plays written by Ibsen including Hedda in Hedda Gabler, Rebecca West in Rosmersholm, Nora in A Doll's House and Hilda Wangel in The Master Builder. These plays were a great success and for the next few years Elizabeth Robins was one of the most popular actresses on the West End stage.

In 1898 Robins joined with her lover, William Archer, to form the New Century Theatre to sponsor non-profit productions of Ibsen. The company produced several plays including John Gabriel Borkman and Peer Gynt. After one production, the actress, Beatrice Patrick Campbell called her performance in "the most intellectually comprehensive piece of work I had seen on the English stage". According to her biographer, Angela V. John: "In the 1890s her incipient feminism had been fuelled by witnessing the exploitation of actresses by actor–managers and by Ibsen's depiction of strong-minded women."

1898 saw the publication of Robins' popular novel The Open Question. In 1900 Elizabeth travelled to Alaska in an attempt to find her brother, Raymond Robins, who had gone missing while on an expedition. Later she wrote about her experiences in Alaska in the novels, Magnetic North (1904) and Come and Find Me (1908).

Raymond returned to the United States and became an important figure in the social reform movement. He was a member of the Hull House settlement in Chicago and served on the national committee of the Progressive Party. In 1905 he married Margaret Dreier, who was later to become president of the Women's Trade Union League (WTUL).

Elizabeth was a strong feminist and initially had been a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. However, disillusioned by the organisation's lack of success, she joined the Women's Social and Political Union. Soon afterwards Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence commissioned Elizabeth to write a series of articles for her journal Votes for Women. She also asked her to write a play on the subject.

Evelyn Sharp saw Elizabeth Robins make a speech on women's suffrage in Tunbridge Wells in 1906: "The impression she made was profound, even on an audience predisposed to be hostile; and on me it was disastrous. From that moment I was not to know again for twelve years, if indeed ever again, what it meant to cease from mental strife; and I soon came to see with a horrible clarity why I had always hitherto shunned causes."

In 1908 two members of the Women's Social and Political Union, Bessie Hatton and Cicely Hamilton formed the Women Writers Suffrage League. Later that year the women formed the sister organisation, the Actresses' Franchise League. Elizabeth Robins became involved in both organisations. So also did the militant suffragette, Kitty Marion. Other actresses who joined included Winifred Mayo, Sime Seruya, Edith Craig, Inez Bensusan, Ellen Terry, Lillah McCarthy, Sybil Thorndike, Vera Holme, Lena Ashwell, Christabel Marshall, Lily Langtry and Nina Boucicault.

Inez Bensusan oversaw the writing, collection and publication of Actresses' Franchise League plays. Pro-suffragette plays written by members of the Women Writers Suffrage League and performed by the AFL included the play Votes for Women by Elizabeth Robins and was performed by suffragists all over Britain. Robins also used the same story and characters for her novel The Convert. Both of these works of art deal with how men sexually exploit women. The heroine in the story, Vida Levering, a militant suffragette, rejects men because in the past, a lover, Geoffrey Stoner, a Conservative MP, forced her into having an abortion because he feared he would lose his inheritance. The heroine was initially named Christian Levering and was based on Elizabeth's close friend, Christabel Pankhurst. When Emmeline Pankhurst raised fears about what the play might do to Christabel's reputation, Elizabeth agreed to change the name to Vida. Elizabeth Robins, like her heroine in the play and novel, turned down offers of marriage from many men, including the playwright, George Bernard Shaw and the publisher William Heinemann.

In 1907 Elizabeth Robins became a committee member of the WSPU. In July 1909, she met Octavia Wilberforce. Octavia later recalled: "It was a turning point in my life… I had always read omnivorously and longed to write myself, and to meet so distinguished an author in the flesh was a terrific adventure. It was a small family luncheon at Phyllis Buxton's house. Elizabeth Robins was dressed in a blue suit, the colour of speedwell, which matched her beautiful deep-set eyes. I was introduced as Phyllis's friend who lives near Henfield... Elizabeth Robins.... with a charming grace and in an unforgettable voice asked me if I would come to tea one day and she would show me her modest little garden." The two women became lovers.

When the British government introduced the Cat and Mouse Act in 1913, Robins used her 15th century farmhouse at Backsettown, near Henfield, that she shared with Octavia Wilberforce, as a retreat for suffragettes recovering from hunger strike. It was also rumoured that the house was used as a hiding place for suffragettes on the run from the police.

Elizabeth wrote a large number of speeches defending militant suffragettes between 1906 and 1912 (a selection of these can by found her book Way Stations). However, Elizabeth herself never took part in these activities and so never experienced arrest or imprisonment. Emmeline Pankhurst told her it was more important that she remained free so that she could use her skills as a writer to support the suffragettes. It was also pointed out that as Elizabeth was not a British citizen she faced the possibility of being deported if she was arrested. Elizabeth once told a friend that she would "rather die than face prison."

Like many members of the WSPU, Elizabeth Robins objected to Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst's dictatorial style of running the organisation. Elizabeth also disapproved of the decision in the summer of 1912 to start the arson campaign. When the Pankhursts refused to reconsider this decision, Robins resigned from the WSPU.

In 1908 Elizabeth became great friends with Octavia Wilberforce, a young woman who had a strong desire to become a doctor. When Octavia's father refused to pay for her studies, Elizabeth arranged to take over the financial responsibility for the course.

After women gained the vote, Robins took a growing interest in women's health care. Robins had been involved in raising funds for the Lady Chichester Hospital for Women & Children in Brighton since 1912. After the First World War Robins joined Louisa Martindale in her campaign for a much more ambitious project, a fifty-bed hospital run by women for women. Elizabeth persuaded many of her wealthy friends to give money and eventually the New Sussex Hospital for Women was opened in Brighton.

Elizabeth Robins also became involved in the campaign to allow women to enter the House of Lords. Elizabeth's friend, Margaret Haig, was the daughter of Lord Rhondda. He was a supporter of women's rights and in his will made arrangements for her to inherit his title. However, when he died in 1918, the Lords refused to allow Viscountess Rhondda to take her seat. Robins wrote numerous articles on the subject, but it was not until 1958, long after Viscountess Haig's death, that women were first admitted to the House of Lords.

Robins remained an active feminist throughout her life. In the 1920s she was a regular contributor to the feminist magazine, Time and Tide. Elizabeth also continued to write books such as Ancilla's Share: An Indictment of Sex Antagonism that explored the issues of sexual inequality.

Elizabeth Robins joined Octavia Wilberforce and Louisa Martindale in their campaign for a new fifty-bed, women's hospital in Brighton. After the New Sussex Hospital for Women in Brighton opened, Octavia became one of the three visiting doctors. Later she was appointed as the hospital's head physician.

In 1927 Octavia Wilberforce helped Elizabeth Robins and Marjorie Hubert set up a convalescent home at Backsettown, for overworked professional women. Wilberforce used the convalescent home as a means of exploring the best way of helping people to become fit and healthy. Patients were instructed not to talk about illness. Octavia believed diet was very important and patients were fed on locally produced fresh food. Whenever possible, patients were encouraged to eat their meals in the garden.

During the Second World War Elizabeth Robins went back to the United States. However, at the age of eighty-eight, she returned to live with Octavia Wilberforce at her home at 24 Montpelier Crescent in Brighton.

One of her regular visitors was Leonard Woolf. He recalled in his autobiography, The Journey Not the Arrival Matters (1969): "Elizabeth was, I think, devoted to Octavia, but she was also devoted to Elizabeth Robins; when we first knew her, she was already a elderly woman and a dedicated egoist, but she was still a fascinating as well as an exasperating egoist. When young she must have been beautiful, very vivacious, a gleam of genius with that indescribably female charm which made her invincible to all men and most women. One felt all this still lingering in her as one sometimes feels the beauty of summer still lingering in an autumn garden. After the war, when she returned from Florida to Brighton, a very old frail woman, she used every so often to ask me to come and see her in bed, surrounded by boxes full of letters, cuttings, memoranda, and snippets of every sort and kind. In stamina I am myself inclined to be invincible, indefatigable, and imperishable, and I was nearly twenty years younger than Elizabeth, but after two or three hours' conversation with her in Montpelier Crescent, I have often staggered out of the house shaky, drained, and debilitated as if I had just recovered from a severe attack on influenza."

Elizabeth Robins died at 24 Montpelier Crescent, Brighton, on 8th May 1952.

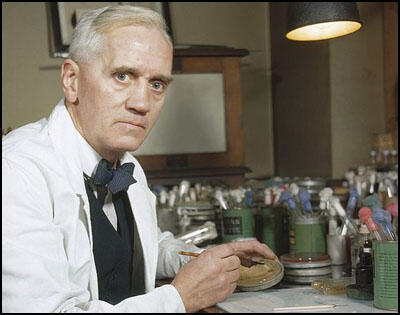

On this day in 1881 scientist Alexander Fleming was born at Lochfield Farm in Darvel. At the age of 12 he attended Kilmarnock Academy. When his father died, his oldest brother Hugh took over the running of the farm.

After leaving school Fleming found work with a shipping company in London. In 1899 the Boer War broke out and in an attempt to escape from a job he hated he joined the London Scottish. Although a good soldier he was indifferent to promotion and was content to remain a private.

In 1901 Fleming was left a legacy by his uncle and he decided to use the money to buy himself out of the army and to study medicine. As he had no formal qualifications, Fleming had to pass an examination before he was allowed to enter medical school. According to one of his biographers: "He had a few lessons, and then applied his prodigious memory and high intelligence to the task, passing top of all the candidates in the UK." He decided to study at St. Mary's Hospital in Paddington.

An outstanding doctor, Fleming was invited to join Almroth Wright at his laboratory at the Inoculation Department. Wright and his colleagues were responsible for developing an anti-typhoid vaccine. Fleming's first success was to take a compound, salvarsan (606), that treated syphilis in rabbits, and develop it so that it could be used on human beings.

On the outbreak of the First World War Fleming joined the Royal Army Medical Corps. Fleming and Almroth Wright were based in Boulogne. Fleming soon discovered that many of the wounded men being transported back from the Western Front were suffering from septicaemia, tetanus and gangrene. He was aware that white blood corpuscles, left to themselves, killed an enormous number of microbes. Yet the infections from war wounds were terrible. Fleming realised that part of the answer was that there was a great deal of dead tissue around the wound, providing a good culture in which microbes could flourish. In September 1915, he published an article in The Lancet advising surgeons to remove as much dead tissue as possible from the area of wounds.

Fleming research showed that the traditional treatment of infected wounds with antiseptics, was totally ineffective when used in the Casualty Clearing Station. He discovered that antiseptics did nothing to prevent gangrene in seriously injured soldiers. The reason for this was that scraps of underclothing and other dirty objects were driven by the force of an explosion deeply into the patient's tissues, where antiseptics were unable to reach.

Fleming and Almroth Wright realised that supporting the natural resources of the body would be more effective in the treatment of gangrene and the showed that a high concentration of saline solution would achieve this. However, they had great deal of difficulty in persuading the Royal Army Medical Corps to adopt this treatment.

One Canadian doctor who visited Boulogne was very impressed with Fleming: "Boulogne being the great supply port of the BEF, there was always a crowd of guests, and the talk grew animated. Though Fleming said little, he did a great deal to keep the conversation at a practical level with his felicitous and opportune remarks and his breadth of outlook. Another doctor who worked with Fleming remarked that "he never said more than he had to, but carried on calmly and efficiently with his work".

Fleming remained convinced that he would eventually find a successful treatment for infected wounds. "Surrounded by all these infected wounds, by men who were suffering and dying without our being able to do anything to help them, I was consumed by a desire to discover, after all this struggling and waiting, something which would kill those microbes."

After the war Fleming returned to St. Mary's Hospital in Paddington and in 1921 Fleming was made assistant director of the Inoculation Department. The following year he discovered lysozyme, a natural antibacterial enzyme which he found initially in human tears.

In 1928 Fleming was appointed as Professor of Bacteriology at the University of London. Later that year he was clearing out some old dishes in which he grew his cultures. On one of the mouldy dishes, he noticed that around the mould, the microbes had apparently been dissolved. He took a small sample of the mould and set it aside. He later identified it as of the penicillium family. He therefore named the anti-bacterial agent he had discovered penicillin.

Fleming published his findings in 1929 but it was not until during the Second World War that Howard Florey and Ernst Chain managed to isolate and concentrate penicillin. It was not until the end of the war that the antibiotic could be mass produced and was widely used. Fleming, Florey and Chain won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1945.

In October 1953 Fleming developed pneumonia. He was given an injection of penicillin. Fleming made a quick recovery and he later commented: "I had no idea it was so good."

Alexander Fleming died from heart failure on 11th March 1955. It was recently estimated that over 200 million lives have been saved by penicillin since 1945.

On this day in 1889 writer John Middleton Murry, the son of a clerk in the inland revenue, was born in Peckham on 6th August 1889. As Kate Fulbrook has pointed out, his father: "John Murry was a determined man from an impoverished and illiterate background who taught himself to write. Poor but ambitious, he saw education as the sole means to fulfil his aspirations for his son. Subjected to intense pressure to learn from the time he could speak, John Middleton Murry could read by the age of two."

He won a scholarship to Christ's Hospital (1901-08) and then won an exhibition and a scholarship to study classics at Brasenose College, Oxford, where he took a first in 1910. The following year he founded and edited the modernist periodical Rhythm.

In 1912 he met the short-story writer, Katherine Mansfield. The couple began living together and Murry began publishing her work in Rhythm. The relationship was very difficult. Vanessa Curtishas pointed out: "Katherine felt superior towards them (men), and had been promiscuous since her late teens, frequently using men for her own pleasure and then moving on once the initial thrill had faded. She fell in love quickly, but until Murry entered the picture, seemed not to possess the stamina needed to develop a relationship more lasting and meaningful."

Katherine Mansfield disliked the traditional role played by women at this time. She wrote in her journal about her relationship with Murry: "I hate hate hate doing these things that you accept just as all men accept of their women... I walk about with a mind full of ghosts of saucepans and primus stoves.... I loathe myself, today. I detest this woman who superintends you and rushes about, slamming doors and slopping water - all untidy with her blouse out and her nails grimed. I am disgusted and repelled by the creature that shouts at you, You might at least empty the pail and wash out the tea-leaves! Yes, no wonder you come over silent."

Murry and Mansfield became close friends with D. H. Lawrence. They were witnesses for the wedding of Lawrence and Frieda von Richthofen in 1914. The two couples established themselves in two cottages near Chesham in Buckinghamshire. According to Claire Tomalin: "Mansfield's reminiscences of New Zealand probably inspired Lawrence with the lesbian episode in The Rainbow (written in winter 1914–15), and she was certainly the model for Gudrun in Women in Love." Later, Mansfield and Murry joined the Lawrences at Higher Tregerthen, near Zennor, in an attempt at communal living. It was a failure and within weeks she and Murry moved on.

Murry became friendly with Philip Morrell and Ottoline Morrell. In 1915 the Morrells purchased Garsington Manor near Oxford and it became a meeting place for left-wing intellectuals. This included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington, Bertram Russell, Leonard Woolf, David Garnett, Desmond MacCarthy, Dorothy Brett, Siegfried Sassoon, D.H. Lawrence, Frieda Lawrence, Ethel Smyth, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, Thomas Hardy, Vita Sackville-West, Herbert Asquith, Harold Nicolson and T.S. Eliot.

In the autumn of 1915 Murry joined forces with D.H. Lawrence and Katherine Mansfield to establish a new magazine called The Signature. Claire Tomalin, the author of Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life (1987) has argued that it was decided "to sell by subscription; it was to be printed in the East End, and the contributors were to have a club room in Bloomsbury for regular meetings and discussions." Sales were poor and the magazine folded after three issues.

Murry also reviewed literature and art for the Westminster Gazette (1912–14) and the Times Literary Supplement (1914–18). In 1916 he published his first significant critical work, Dostoevsky. During the First World War Murry worked in the War Office in the political intelligence department as editor of the confidential Daily Review of the Foreign Press.

Mark Gertler claimed that at one of the parties at Garsington Manor he "made violent love to Katherine Mansfield! She returned it, also being drunk. I ended the evening by weeping bitterly at having kissed another man's woman and everyone was trying to console me. Mansfield told Frieda Lawrence that she was in love with Gertler. Frieda accused Mansfield of leading the younger man on, and threatened never to speak to her again.

Katherine Mansfield became very ill and in December 1917 tuberculosis was diagnosed, and she was told she must go to a warmer climate. She settled in Bandol on the south coast of France. In January 1918, she suffered her first haemorrhage. She now decided to return to London and on 3rd May 1918 she married John Middleton Murry at Kensington Register Office. They rented a house close to Hampstead Heath, and Mansfield persuaded Ida Baker to give up her job and become their housekeeper.

After the war he became editor of The Athenaeum, where he championed modernism in literature and provided a platform for the work of writers such as George Santayana, Paul Valéry, D. H. Lawrence, Aldous Huxley, Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, E. M. Forster, T. S. Eliot, and Virginia Woolf. In 1922 he published his most important work, The Problems of Style.

Murray helped Mansfield's work to become known to the reading public. Vanessa Curtis, the author of Virginia Woolf's Women (2002): "Ironically, as Katherine began to blossom as a writer and receive serious recognition for her work, her health began to slip away, firstly with a recurrence of gonorrhoea and then with the onset of the tuberculosis that was to kill her. Photographs record her plumpness falling away from her bones, her body becoming gaunt, her eyes looking eerily big and scared in a pale, drawn face. She was forced, by the dangers of wintering in cold England, to go to the south of France, alone and away from Murry."

Murry gave Mansfield work reviewing fiction for The Athenaeum, and he negotiated the publication of her second collection, Bliss and other Stories, with Constable, in December 1920. The publication of her third collection, The Garden Party and other Stories, in February 1922 brought her, according to Claire Tomalin, "great and deserved acclaim." Later that month she went to Paris, where a Russian doctor was offering a new treatment for tuberculosis by irradiating the spleen with X-rays. She told Dorothy Brett: "If I were a proper martyr I should begin to have that awful smile that martyrs in the flames put on when they begin to sizzle". On her return she went to live with Brett in Hampstead.

Mansfield knew she was dying and wrote in her journal: "My spirit is nearly dead. My spring of life is so starved that it's just not dry. Nearly all my improved health is pretence - acting". She added that she hoped she would live long enough to enjoy "a garden, a small house, grass, animals, books, pictures, music and life.

In 1922 Murry began an affair with Dorothy Brett. She thought she was pregnant and wrote to a friend: "I am afraid I have struggled through a terrible time of depression... The worry, the fear exhausts me... I feel, as I suppose every woman feels, that the burden is all left to me. Murry can turn from one woman to another while I have to face the beastliness of an illegal operation - or the long strain of carrying a child and perhaps death - not that I mind the last - it might be the best way out if I am not strong enough to stand alone." Murry arranged an abortion for Brett but she miscarried before she had the operation.

Alfred Richard Orage, the editor of The New Age, told Katherine Mansfield about the ideas of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, a Greek-Armenian guru with a new establishment, the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, at Fontainebleau. In October 1922 Ida Baker accompanied Mansfield to the clinic but was then sent away. John Middleton Murry visited her on 9th January 1923. That evening as she went up the stairs she began to cough, a haemorrhage started, she said "I believe… I'm going to die" and according to Murry she was dead within minutes. On 12th January Mansfield was buried in the nearby cemetery at Avon. Only Murry, Baker, Dorothy Brett, and two of her sisters went to the funeral.

After her death two further collections of short stories were published: The Dove's Nest (1923) and Something Childish (1924). John Middleton Murry edited and arranged for the publication of her Journals (1927) and The Letters of Katherine Mansfield (1928). According to Claire Tomalin: "Murry inherited her manuscripts and over the next two decades he edited and published almost all her remaining stories and fragments, her journals, her poems, her reviews, and her letters. In doing so he presented to the world an image of a saintly young woman and suppressed the darker aspects of her character and experience, perhaps understandably, given the conventions of the time. He also made a good income out of her considerable royalties. Not a penny went to Ida Baker."

After the death of Katherine Mansfield he founded and edited The Adelphi. In 1927 Murry appointed Richard Rees as editor of the journal. Rees later recalled: "He possessed the most original and brilliant and in some ways the most penetrating mind I have ever known at close quarters; and it is a remarkable fact that, while I have had a number of friends who have been widely admired and lavishly and deservedly praised, Murry has been consistently and often venomously denigrated, misrepresented, or when possible - though this was not so easy - ignored."

In 1929 Middleton Murry met Max Plowman. Both men were socialist pacifists. According to Richard A. Storey: "Plowman first met the writer and critic John Middleton Murry early in 1929 and the remaining years of his life were marked by a growing friendship and debate with Murry and an active, though still highly critical, involvement in pacifist affairs as the world situation deteriorated."

Murry became a Marxist and in 1931 he published The Necessity of Communism. In the he argued: "All the energy that I can afford is spent in trying (i) to help the workers to struggle intelligently, and (ii) to convert as many bourgeois as I can to an understanding of the necessity and validity of that struggle.... I know by experience that the English worker is a fundamentally decent man: and that nothing sickens him (or me) more than the knowledge that his decency has been exploited. If I can help to give him, or the natural leaders he can really trust, a brand of Marxism worthy of him, and one that will help to safeguard him from this deception, I conceive I am doing what I am best fitted to do in the cause."

In 1931 he joined the Independent Labour Party. His editor, Richard Rees reluctantly joined him in the ILP: "With my political experience from the 1920s I was well aware that, from any practical point of view, Murry was making an error when he joined the I.L.P. at the end of 1931. But since I was at that time playing Engels to his Marx I was obliged to follow suit."

On 16th October 1934, Richard Sheppard, a canon of St. Paul's Cathedral, had a letter published in the Manchester Guardian inviting people to send him a postcard giving their undertaking to "renounce war and never again to support another." Within two days 2,500 men responded and over the next few weeks around 30,000 pledged their support for Sheppard's campaign. The following year he formed the Peace Pledge Union. Middleton Murry became a strong supporter of the PPU. Other members included George Lansbury, Vera Brittain, Max Plowman, Arthur Ponsonby, Wilfred Wellock, Maude Royden, Siegfried Sassoon, Donald Soper, Aldous Huxley, Laurence Housman and Bertrand Russell.

In 1934 Middleton Murry purchased a farm in Langham, Essex. Murry and Max Plowman established a pacifist community centre they called Adelphi Centre on the land. Murry argued he was attempting to create "a community for the study and practice of the new socialism". Plowman organised summer schools where people such as George Orwell, John Strachey, Jack Common, Herbert Read and Reinhold Niebuhr lectured on politics, philosophy and literature. During the Spanish Civil War the farm was handed over to the Peace Pledge Union. They used it to house some 60 Basque refugee children. Middleton Murry now became an outspoken pacifist, writing The Necessity of Pacifism (1937).

Max Plowman continued to work for The Adelphi. When Richard Rees resigned as editor Middleton Murry resumed editorship until 1938, when Plowman took on the role. Richard A. Storey has argued: "Although he lacked the benefit of a university education, Plowman's passionate commitment to literature, which achieved scholarly status in his work on Blake and with which his pacifist philosophy was closely connected, provided both his raison d'être and the livelihood for himself and his family."

On the outbreak of the Second World War the Adelphi Centre became home for some twenty elderly evacuees from from Bermondsey, Bow and Bethnal Green. It was also a co-operative farm of 70 acres with a group of young conscientious objectors. However, as Andrew Rigby pointed out: "As in the case of so many community projects, factions developed between the dozen or so individualists who made up the membership. Murry was subjected to a lot of criticism as he insisted on retaining financial control of the farm, having invested all his capital in the project."

Middleton Murry, with the help of Wilfred Wellock, edited the weekly newspaper, Peace News, from 1940 to 1946. He wrote on 22nd June, 1945, that he was having doubts about his pacifism: "I misjudged two things. First I misjudged the nature of the average decent man, for whom non-violent resistance is infinitely more difficult and less natural than violent. The second mistake was even more serious. I gravely underestimated the terrible power of scientific terrorism as developed by the totalitarian police-states... I am therefore constrained in honesty to admit that under neither the Nazi nor the Soviet system of systematic and applied brutality does non-violent resistance stand a dog's chance... In a word, it seems to me that the scientific terrorism of the totalitarian police state - the wholesale reversion to medieval torture, with all the diabolical ingenuity of applied modern science - has changed the whole frame of reference within which modern pacifism was conceived."

John Middleton Murry died of a heart attack on 13th March 1957 in the West Suffolk Hospital, Bury St Edmunds.

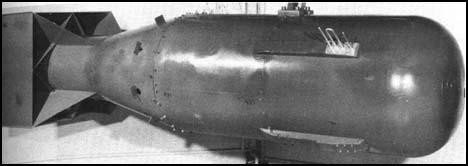

On this day in 1945, a B29 bomber piloted by Paul Tibbets, dropped an atom bomb on Hiroshima. Michihiko Hachiya was living in the city at the time: "Hundreds of people who were trying to escape to the hills passed our house. The sight of them was almost unbearable. Their faces and hands were burnt and swollen; and great sheets of skin had peeled away from their tissues to hang down like rags or a scarecrow. They moved like a line of ants. All through the night, they went past our house, but this morning they stopped. I found them lying so thick on both sides of the road that it was impossible to pass without stepping on them."

Later that day President Harry S. Truman made a speech where he argued: "The harnessing of the basic power of the universe. The force from which the sun draws its power has been used against those who brought war to the Far East. We have spent $2,000,000,000 (about $500,000,000) on the greatest gamble in history, and we have won. With this bomb we have now added a new and revolutionary increase in destruction to supplement the growing power of our armed forces. In their present form these bombs are now in production and even more powerful forms are in development."

Truman then issued a warning to the Japanese government: "We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories and their communications. Let there be no mistake, we shall completely destroy Japan's power to make war. It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued from Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of run from the air the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with a fighting skill of which they have already become well aware."

The journalist, John Hersey, reported that the dropping of the atom bomb was having long term consequences: "Dr. Sasaki and his colleagues at the Red Cross Hospital watched the unprecedented disease unfold and at last evolved a theory about its nature. It had, they decided, three stages. The first stage had been all over before the doctors even knew they were dealing with a new sickness; it was the direct reaction to the bombardment of the body, at the moment when the bomb went off, by neutrons, beta particles, and gamma rays. The apparently uninjured people who had died so mysteriously in the first few hours or days had succumbed in this first stage. It killed ninety-five per cent of the people within a half-mile of the center, and many thousands who were farther away. The doctors realized in retrospect that even though most of these dead had also suffered from burns and blast effects, they had absorbed enough radiation to kill them. The rays simply destroyed body cells - caused their nuclei to degenerate and broke their walls. Many people who did not die right away came down with nausea, headache, diarrhea, malaise, and fever, which lasted several days. Doctors could not be certain whether some of these symptoms were the result of radiation or nervous shock. The second stage set in ten or fifteen days after the bombing. Its first symptom was falling hair. Diarrhea and fever, which in some cases went as high as 106, came next. Twenty-five to thirty days after the explosion, blood disorders appeared: gums bled, the white-blood-cell count dropped sharply, and petechiae (eruptions) appeared on the skin and mucous membranes. The drop in the number of white blood corpuscles reduced the patient's capacity to resist infection, so open wounds were unusually slow in healing and many of the sick developed sore throats and mouths. The two key symptoms, on which the doctors came to base their prognosis, were fever and the lowered white-corpuscle count. If fever remained steady and high, the patient's chances for survival were poor."

One survivor described the death of her daughter from radiation sickness. "She had no burns and only minor external wounds. She was quite all right for a while. But on the 4th September, she suddenly became sick. She had spots all over her body. Her hair began to fall out. She vomited small clumps of blood many times. I felt this was a very strange and horrible disease. We were all afraid of it, and even the doctor didn't know what it was. After ten days of agony and torture, she died on September 14th." It has been estimated that over the years around 200,000 people have died as a result of this bomb being dropped.

Japan did not surrender immediately and a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki three days later. On 15th August the Japanese surrendered. The Second World War was over.

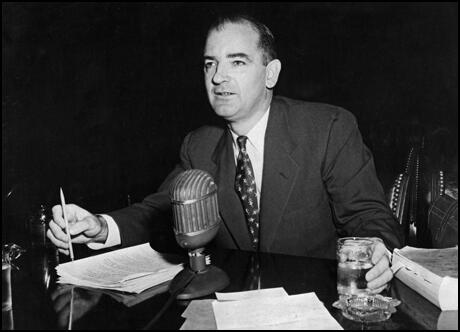

On this day in 2009 Michael Freedland argued that McCarthyism was about purging Jews. Freedland explained in unting communists? They were really after Jews:

It was a milestone in Hollywood history - actors, writers, producers blacklisted for their political beliefs. Sixty years ago, men and women, some of them with flourishing careers, were made to answer the question: "Are you now, or have you ever been, a communist?"

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), anticipating the "investigations" of Senator Joseph McCarthy shortly afterwards, chose Hollywood for the start of its onslaught against communism. At least, that is what they said they were doing. But any investigation into the investigations, to coin a phrase, reveals it was something else. For "communist", read "Jew".

The hearings that took place in Los Angeles and in Washington between 1947 and the mid-'50s were as much (some would say more) antisemitic as anti-Communist. Hollywood was chosen for the attack because of the great publicity value the movie capital offered. It was also a great opportunity to get at the Jews of Hollywood. One after the other, the people called to give evidence to HUAC (in effect, put on trial by the committee) were Jews - not exclusively so, but enough to make the case.

On the floor of the House of Representatives itself, Congressman John Rankin made a speech which consisted of virtually nothing more than a list of Jewish names. The wife of the actor Melvin Douglas, Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas - whom a certain HUAC member named Richard Milhous Nixon had insulted by saying she was "pink, down to her underwear" - asked which films the committee really believed were helping the Communist Party. Rankin answered by reading some of the names that had appeared on a petition to congress: "One is Danny Kaye," he began. "We found his real name was David Daniel Kaminsky. Then there was Eddie Cantor. His real name was Edward (sic) Iskowitz. Edward G Robinson, his name is Emmanuel Goldenberg." The final cut was when he added, almost as an afterthought, the name of the congresswoman's husband: "There's another one here who calls himself Melvyn Douglas, whose real name is Melvyn Hesselberg."

The musician Larry Adler, a refugee from Hollywood after being warned he was about to be put on the blacklist, told me shortly before his death: "What was worse were the letters Rankin wrote. One I saw began, ‘Dear Kike'."

The petition Rankin mentioned was in support of the so-called Hollywood Ten, most of whom were writers, jailed after being denied the opportunity of making a statement in their defence. They were unable to claim either the First Amendment, guaranteeing freedom of speech, or the Fifth, which said they could not be asked to incriminate themselves. Six of the 10 - John Howard Lawson, Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz and Samuel Ornitz - were Jews.

Their appeal to the Supreme Court was rejected. The original chairman of HUAC, Martin Dies, had invoked the 1918 Sedition Act, which declared that anyone who was foreign-born (even if subsequently naturalised) could be declared a "non-citizen" - because "there are too many Jews in Hollywood".

The most important Jews in Hollywood were, of course, the studio bosses - people like the Warner Brothers, Louis B Mayer of MGM, and Harry Cohn of Columbia. They were among those responsible for the Waldorf Declaration - a statement issued after a gathering at the New York hotel which declared that they would never employ a communist. The only one who would not sign was Samuel Goldwyn (born Shmuel Gelbfisch), who said that nobody was going to tell him how to run his operation.

The signatories were cowards. They were scared that if they did not come out in support of HUAC , they themselves would be condemned as communists, resulting in the collapse of their businesses. Once on the blacklist, actors could not get parts, writers could not submit scripts, directors could not get work.

Writers, however, did learn how to use "fronts" (Woody Allen made a film using blacklisted actors and writers - nearly all of them Jewish - called The Front, about a writer getting a restaurant cashier to submit scripts in his name). Actors had many more difficulties. No one could prove that Edward G Robinson was a communist, but he had a reputation for being left-wing. So this superstar was put on a "grey list". Warners would not give him more than a few subsidiary roles in "B" pictures and ordered an article to be published under his name, called "The Reds Made A Sucker of Me".

He was luckier than many. The tough guy actor John Garfield (originally Jules Garfinkle) died from a heart attack at the age of 39 on the eve of being called before HUAC. The blacklisted star of the hit radio and TV series The Goldbergs, Philip Loeb, booked himself into an hotel, ordered champagne from room service and then jumped from the skyscraper building window. It was a scene recalled in The Front by Zero Mostel, another blacklist victim. One scene in the film was taken from Mostel's own story. Walter Bernstein, the blacklistee who wrote the film, told me about the actor, whose busy life had previously included cabaret appearances at Jewish resort hotels in the Catskill mountains. Mostel was out of work."I took him up to the Concord, where he had been used to getting $2,000 a night," said Bernstein. "Now he was only to get $500. His rate was then cut even more. There were 2,000 people there. They loved it. He cursed them in Yiddish and the more he cursed them the more they liked it."

Several Jewish actors and directors came to live in London - like Carl Foreman who had the indignity of seeing his script for the film Bridge on the River Kwai win an Oscar but awarded to the French writer Pierre Boulle instead. Larry Adler's score for the movie Genevieve was nominated for an Academy Award - in the name of the musical director Muir Mathieson. "I was pleased to see that it didn't win," he told me.

A leading Broadway actor, J Edward Bromberg came to Britain, too, after being blacklisted - and died of a heart attack. The Jewish actress Lee Grant was blacklisted for speaking at a memorial service for Bromberg. She was told she could get off the list if she named her husband as a communist. She refused - and did not work for 12 years. Bromberg "died of a broken heart", the Israeli-born actor Theodore Bikel told me. "He was a victim of those antisemites, those fascists."

The blacklist lasted for those 12 years, but ended because of Jews, too. Kirk Douglas (Issur Danielovich) with Spartacus, and Otto Preminger, who was directing Exodus, insisted that the writer of both films, the Hollywood Ten member Dalton Trumbo, should use his real name, not a nom de plume. "I have been working for Hollywood for 60 years, made 85 pictures," said Douglas. "The thing I am most proud of is breaking the blacklist."