On this day on 5th September

On this day in 1548 women's rights campaigner, Catherine Parr, died. She gave birth to a daughter named Mary on 30th August 1548. After the birth, Catherine developed puerperal fever. Her delirium took a painful form of paranoid ravings about her husband and others around her. Catherine accused the people around her of standing "laughing at my grief". She told the women attending her that her husband did not love her. Thomas Seymour held her hand and replied "sweetheart, I would do you no hurt". Seymour is reported to have lain down beside her, but Catherine asked him to leave because she wanted to have a proper talk with the physician who attended her delivery, but dared not for fear of displeasing him.

The fever eventually went and she was able to dictate her will calmly, revealing that Thomas Seymour was the "great love of her life". Queen Catherine, "sick of body but of good mind", left everything to Seymour, only wishing her possessions "to be a thousand times more in value" than they were. Catherine, thirty-six years old, died on 5th September 1548, six days after the birth of her daughter.

After the death of her second husband, Catherine Parr fell in love with Thomas Seymour, the brother of Queen Jane Seymour and Edward Seymour. It has been pointed out by David Starkey, the author of Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (2003): "Edward Seymour was dashing and rather dangerous. That Catherine found him so attractive suggests hidden emotional depths. Or rather, perhaps, very human shallows after a lifetime of doing what she ought, as a daughter and a wife, a little of what she fancied might have seemed irresistibly appealing."

It would seem that Catherine was on the verge of marrying Seymour when she met Henry VIII. He was immediately attracted to Catherine. Susan E. James has argued: "Print and film alike have represented Catherine as an ageing, plain-faced, pious widow with few attractions, selected by the king for her talents as a nurse. This is a misleading image that does not hold up beneath the weight of contemporary evidence. She was of medium height, with red hair and grey eyes. She had a lively personality, was a witty conversationalist with a deep interest in the arts, and an erudite scholar who read Petrarch and Erasmus for enjoyment. She was a graceful dancer, who loved fine clothes and jewels, particularly diamonds, and favoured the colour crimson in her gowns and household livery. Catherine also conveyed a sense of her own value, independent of the marital relationship, which was rare for a woman of this period."

Henry asked Catherine to become his sixth wife. She was in a difficult position. Although she was deeply in love with Thomas Seymour, it was made clear to her, that her reluctance to accept the king as her husband was to defy God's will. Catherine wrote to Seymour "my mind was fully bent the other time I was at liberty to marry you before any man I know". However she decided to marry Henry. Jane Dunn, the author of Elizabeth & Mary (2003) has pointed out: "In marrying the King rather than this love, Catherine Parr had sacrificed her heart for the sake of duty." It has also been suggested that Catherine accepted his proposal for religious reasons: "She was marrying Henry at God's command and for His purpose. And that purpose was no less than to compete the conversion of England to Reform."

Catherine Parr married Henry VIII on 12th July, 1543, at Hampton Court with eighteen people in attendance. A few days later, the King and Queen left on what turned out to be a protracted honeymoon that kept them away from London for the rest of the year. First they travelled into Surrey to visit some of Henry's favourite hunting parks at Oatlands, Woking, Guildford and Sunninghill. They spent several months at Ampthill Castle, the former home of Thomas Wolsey. The plague was particularly virulent in London that summer and autumn and they did not return to the capital until December.

Catherine inherited three step-children, Mary (27), Elizabeth (9) and Edward (6). Queen Catherine became an excellent step-mother. Antonia Fraser, the author of The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1992) points out: "It is greatly to her credit that she managed to establish excellent loving relations with all three of her step-children, despite their very different needs and ages (the Lady Mary was twenty-one years older than Prince Edward). Of course she did not literally install them under one roof: that is to misunderstand the nature of sixteenth-century life when separate households were more to do with status than inclination. At the same time, the royal children were now all together on certain occasions, under the auspices of their stepmother... But the real point was that Catherine was considered by the King - and the court - to be in charge of them, an emotional responsibility rather than a physical one."

Elizabeth did not see very much of her father. On 31st July 1544, she wrote to Catherine asking if she could spend time with the royal couple at Hampton Court. "Inimical fortune, envious of all good and ever revolving human affairs, has deprived me for a whole year of your most illustrious presence, and, not thus content, has yet again robbed me of the same good; which thing would be intolerable to me, did I not hope to enjoy it very soon. And in this my exile I well know that the clemency of your Highness has had as much care and solicitude for my health as the King's Majesty himself. By which thing I am not only bound to serve you, but also to revere you with filial love, since I understand that your most illustrious Highness has not forgotten me every time you have written to the King's Majesty, which, indeed, it was my duty to have requested from you. For heretofore I have not dared to write to him. Wherefore I now humbly pray your most excellent Highness, that, when you write to his Majesty, you will condescend to recommend me to him, praying ever for his sweet benediction, and similarly entreating our Lord God to send him best success, and the obtaining of victory over his enemies, so that your Highness and I may, as soon as possible, rejoice together with him on his happy return. No less pray I God that he would preserve your most illustrious Highness; to whose grace, humbly kissing your hands, I offer and recommend myself."

During the summer of 1544 Henry VIII led a military expedition to France. "During his absence Henry appointed his queen regent-general, together with a regency council dominated by the queen's fellow religionists.... This assumption of power, not merely by a woman but by a woman who only a year before had been a Yorkshire housewife, made the queen enemies, particularly among the religious conservatives who resented her evangelical beliefs." While he was away Catherine wrote him several letters about events at home. According to Antonia Fraser they were "remarkably well-written." Catherine took this opportunity to bring Princess Elizabeth back to court. From the middle of July until the middle of September she kept the royal children with her at Hampton Court.

Henry VIII formed an alliance with Charles V. In 1545 a treaty between the two kings included the proposal that Prince Edward marry Charles V's daughter, Maria and that Mary would marry Charles V himself. Elizabeth's future was also discussed and it was suggested that she should marry Charles V's son and heir, Philip of Spain, although that failed to go beyond the initial stages of negotiation. It is claimed that during discussions "Charles was polite, but not encouraging."

Henry, who was in poor health (although it was treason to say so), had agreed a new Act of Succession that stated that in the case of his death the throne would pass to his son Edward and his heirs, but, if Edward died without children, Princess Mary would succeed to the throne. If she, too, died without heirs, the throne would pass to Princess Elizabeth. He excluded his elder sister, Margaret Tudor (she had died in 1541) and her heirs, who were the royal family of Scotland. This included her granddaughter, Mary Stuart.

Catherine Parr wrote several small books on religious matters. It has been pointed out that Catherine was one of only eight women who had books published in the sixty-odd years of the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII. These books showed that she was an advocate of Protestantism. In the book, The Lamentation of a Sinner Catherine describes Henry as being "godly and learned" and being "our Moses" who "hath delivered us out of the captivity and bondage of Pharaoh (Rome)"; while the "Bishop of Rome" is denounced for "his tyranny".

As David Loades, the author of has pointed out, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (2007): "The Queen meanwhile continued to discuss theology, piety and the right use the bible, both with her friends and also with her husband. This was a practice, which she had established in the early days of their marriage, and Henry had always allowed her a great deal of latitude, tolerating from her, it was said, opinions which no one else dared to utter. In taking advantage of this indulgence to urge further measures of reform, she presented her enemies with an opening."

Catherine Parr also criticised legislation that had been passed in May 1543 that had declared that the "lower sort" did not benefit from studying the Bible in English. The Act for the Advancement of the True Religion stated that "no women nor artificers, journeymen, serving men of the degree of yeomen or under husbandmen nor labourers" could in future read the Bible "privately or openly". Later, a clause was added that did allow any noble or gentlewoman to read the Bible, this activity must take place "to themselves alone and not to others". Catherine ignored this "by holding study among her ladies for the scriptures and listening to sermons of an evangelical nature".

In July 1544 Catherine Parr arranged for John Cheke to become tutor to Prince Edward. John Guy has argued the "reformed cause" was revived at Court after Henry VIII married his sixth wife: "Catherine used her influence to mitigate the Act of Six Articles in several cases. Her immediate circle was centred on the royal nursery, where John Cheke, Richard Cox, Anthony Cooke, and other 'reforming' humanists were appointed tutors to Prince Edward and Princess Elizabeth." It has been suggested that Cheke was an humanist scholar in the tradition of Desiderius Erasmus but it was possible that he was a supporter of Martin Luther and this could explain Edward's support for religious reform. Cheke also arranged for Princess Elizabeth to be taught by William Grindal and Roger Ascham.

In February 1546 conservatives, led by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, began plotting to destroy Catherine. Gardiner had established a reputation for himself at home and abroad as a defender of orthodoxy against the Reformation. On 24th May, Gardiner ordered the arrest of Anne Askew and Sir Anthony Kingston, the Constable of the Tower of London, was ordered to torture Askew in an attempt to force her to name Catherine and other leading Protestants.

The Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley and his assistant, Richard Rich took over operating the rack, after Kingston complained about having to torture a woman. Despite suffering a long period on the rack, Askew refused to name those who shared her religious views. According to Askew: "Then they did put me on the rack, because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen, to be of my opinion... the Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands, till I was nearly dead. I fainted... and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours arguing with the Lord Chancellor, upon the bare floor... With many flattering words, he tried to persuade me to leave my opinion... I said that I would rather die than break my faith." On 16th July, 1546, Askew "still horribly crippled by her tortures but without recantation, was burnt for heresy".

Bishop Stephen Gardiner had a meeting with Henry VIII and raised concerns about Catherine's religious beliefs. Henry, who was in great pain with his ulcerated leg and at first he was not interested in Gardiner's complaints. However, eventually Gardiner got Henry's agreement to arrest Catherine and her three leading ladies-in-waiting, "Herbert, Lane and Tyrwhit" who had been involved in reading and discussing the Bible.

David Loades has explained that "the greatest secrecy was observed, and the unsuspecting Queen continued with her evangelical sessions". However, the whole plot was leaked in mysterious circumstances. "A copy of the articles, with the King's signature on it, was accidentally dropped by a member of the council, where it was found and brought to Catherine, who promptly collapsed. The King sent one of his physicians, a Dr Wendy, to attend upon her, and Wendy, who seems to have been in the secret, advised her to throw herself upon Henry's mercy."

Catherine told Henry that "in this, and all other cases, to your Majesty's wisdom, as my only anchor, Supreme Head and Governor here in earth, next under God". He reminded her that in the past she had discussed these matters. "Catherine had an answer for that too. She had disputed with Henry in religion, she said, principally to divert his mind from the pain of his leg but also to profit from her husband's own excellent learning as displayed in his replies." Henry replied: "Is it even so, sweetheart? And tended your arguments to no worse end? Then perfect friends we are now again, as ever at any time heretofore." Gilbert Burnett has argued that Henry put up with Catherine's radical views on religion because of the good care she took of him as his nurse.

The next day Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley arrived with a detachment of soldiers to arrest Catherine. Henry told him he had changed his mind and sent the men away. Glyn Redworth, the author of In Defence of the Church Catholic: The Life of Stephen Gardiner (1990) has disputed this story because it relies too much on the evidence of John Foxe, a leading Protestant at the time. However, David Starkey, the author of Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (2003) has argued that some historians "have been impressed by the wealth of accurate circumstantial detail, including, in particular, the names of Catherine's women."

Henry's health continued to cause concern. Dr. George Owen, the royal physician, who was paid £100 a year to treat the king, told the Privy Council in December, 1546, that he was dying. The Privy Council, now under the control of religious radicals such as John Dudley, Edward Seymour and Thomas Seymour decided to keep the news secret. On 24th December, Catherine took Mary and Elizabeth to stay at Greenwich Palace for the holidays. On their return they were told that Henry was too ill to see them.

Henry VIII died on 28th January, 1547. The following day Edward and his thirteen year-old sister, Elizabeth, were informed that their father had died. According to one source, "Edward and his sister clung to each other, sobbing". Edward VI's coronation took place on Sunday 20th February. "Walking beneath a canopy of crimson silk and cloth of gold topped by silver bells, the boy-king wore a crimson satin robe trimmed with gold silk lace costing £118 16s. 8d. and a pair of ‘Sabatons’ of cloth of gold."

Edward was only nine years old and was too young to rule. In his will, Henry had nominated a Council of Regency, made up of 16 nobles and churchman to assist him in governing his new realm. His uncle, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, emerged as the leading figure in the government and was given the title Lord Protector. He was now arguably the most influential person in the land.

His brother, Thomas Seymour, although he was in his late thirties, proposed to the Council that he should marry the 13-year-old, Elizabeth, but he was told this was unacceptable. He now set his sights on Catherine Parr. At the time he was described as "being gifted with charm and intelligence... and a handsome appearance".Just a few weeks after Henry's death Catherine wrote to Seymour: "I would not have you think that this mine honest good will toward you to proceed from any sudden motion of passion; for, as truly as God is God, my mind was fully bent, the other time I was at liberty, to marry you before any man I know. Howbeit, God withstood my will therein most vehemently for a time, and... made that possible which seemed to me most impossible."

The historian, Elizabeth Jenkins, believes that the "Queen Dowager, released from the sufferings of her marriage to Henry VIII, behaved like an enamoured girl." Seymour wanted to marry Parr but realised the Council would reject his proposal, as it would be pointed out that if she became pregnant, there would have been uncertainty about whether the child was Seymour's or Henry's. Seymour married Parr in secret in about May 1547.

Seymour visited Parr in her home in Chelsea before the news of their marriage was announced. This created extra problems as Elizabeth and Lady Jane Grey were also living with Parr at this time. It has been pointed out that "Elizabeth was still only thirteen when her stepmother, of whom she was most fond, married for love. The young Princess remained in her care, living principally with her at her dower houses at Chelsea and Hanworth. Ever curious and watchful, Elizabeth could not fail to have noted the effects of the sudden transformation in Catherine Parr's life. From patient, pious consort of an ailing elderly king she had been transmuted into a lover, desired and desiring." Parr also appointed Miles Coverdale as her almoner.

Catherine Parr, who was now thirty-five, became pregnant. Although she had been married three times before, it was her first pregnancy. It came as a great shock as Catherine was assumed to be "barren". Thomas Seymour now began paying more attention to Elizabeth. Katherine Ashley, Elizabeth's governess, later recorded: "Seymour... would come many mornings into the Lady Elizabeth's chamber, before she were ready, and sometimes before she did rise. And if she were up, he would bid her good morrow, and ask how she did, and strike her upon the back or on the buttocks familiarly, and so go forth through his lodgings; and sometime go through to the maidens and play with them, and so go forth... If Lady Elizabeth was in bed, he would... make as though he would come at her. And he would go further into the bed, so that he could not come at her." On one occasion Ashley saw Seymour try to kiss her while she was in bed and the governess told him to "go away for shame". Seymour became more bold and would come up every morning in his nightgown, "barelegged in his slippers".

According to Elizabeth Jenkins, the author of Elizabeth the Great (1958): "Queen Dowager took to coming with her husband on his morning visits and one morning they both tickled the Princess as she lay in her bed. In the garden one day there was some startling horse-play, in which Seymour indulged in a practice often heard of in police courts; the Queen Dowager held Elizabeth so that she could not run away, while Seymour cut her black cloth gown into a hundred pieces. The cowering under bedclothes, the struggling and running away culminated in a scene of classical nightmare, that of helplessness in the power of a smiling ogre... The Queen Dowager, who was undergoing an uncomfortable pregnancy, could not bring herself to make her husband angry by protesting about his conduct, but she began to realize that he and Elizabeth were very often together."

Jane Dunn has controversially argued that Elizabeth was a willing victim in these events: "Although not legally her step-father, Thomas Seymour assumed his role as head of the household and with his manly demeanour and exuberant animal spirits he became for the young Princess a charismatic figure of attraction and respect. Some twenty-five years her senior, Seymour in fact was old enough to be her father and the glamour of his varied heroic exploits in war and diplomatic dealings brought a welcome worldly masculinity into Elizabeth's cloistered female-dominated life.... Elizabeth was also attractive in her own right, tall with fair reddish-gold hair, fine pale skin and the incongruously dark eyes of her mother, alive with unmistakable intelligence and spirit. She was young, emotionally inexperienced and understandably hungry for recognition and love. She easily became a willing if uneasy partner in the verbal and then physical high jinks in the newly sexualised Parr-Seymour household."

Anna Whitelock, the author Elizabeth's Bedfellows: An Intimate History of the Queen's Court (2013) dismisses this idea but admits that it is not easy understanding Catherine Parr's motivation in these events. "On two mornings, at Hanworth in Middlesex, another of Catherine's residences, the queen dowager herself joined Seymour in his visit to Elizabeth's Bedchamber and on this occasion they both tickled the young princess in her bed. Later that day, in the garden, Seymour cut Elizabeth's dress into a hundred pieces while Catherine held her down. The involvement of Catherine here is even more puzzling than that of the others. She had fallen pregnant soon after the marriage, so perhaps this made her jealousy more intense and her behaviour more reckless; maybe she was seeking to maintain Seymour's affection and interest in her by joining in his 'horseplay'. Perhaps she feared that Elizabeth was developing something of a teenage infatuation with her stepfather."

Sir Thomas Parry, the head of Elizabeth's household, later testified that Thomas Seymour loved Elizabeth and had done so for a long time and that Catherine Parr was jealous of the fact. In May 1548 Catherine "came suddenly upon them, where they were all alone, he having her (Elizabeth) in his arms, wherefore the Queen fell out, both with the Lord Admiral and with her Grace also... and as I remember, this was the cause why she was sent from the Queen." Later that month Elizabeth was sent away to stay with Sir Anthony Denny and his wife, at Cheshunt. It has been suggested that this was done not as punishment but as a means of protecting the young girl. Philippa Jones, the author of Elizabeth: Virgin Queen (2010) has suggested that Elizabeth was pregnant with Seymour's child.

Elizabeth wrote to Catherine soon after she left her home: "Although I could not be plentiful in giving thanks for the manifold kindness received at your highness' hand at my departure, yet I am something to be borne withal, for truly I was replete with sorrow to depart from your highness, especially leaving you undoubtful of health. And albeit I answered little, I weighed it more deeper when you said you would warn me of all evils that you should hear of me; for if your grace had not a good opinion of me, you would not have offered friendship to me that way that all men judge the contrary. But what may I more say than thank God for providing such friends to me, desiring God to enrich me with their long life, and me grace to be in heart no less thankful to receive it than I now am glad in writing to show it. And although I have plenty of matter, here I will stay for I know you are not quiet to read."

Catherine Parr gave birth to a daughter named Mary on 30th August 1548. After the birth, Catherine developed puerperal fever. Her delirium took a painful form of paranoid ravings about her husband and others around her. Catherine accused the people around her of standing "laughing at my grief". She told the women attending her that her husband did not love her. Thomas Seymour held her hand and replied "sweetheart, I would do you no hurt". Seymour is reported to have lain down beside her, but Catherine asked him to leave because she wanted to have a proper talk with the physician who attended her delivery, but dared not for fear of displeasing him.

The fever eventually went and she was able to dictate her will calmly, revealing that Thomas Seymour was the "great love of her life". Queen Catherine, "sick of body but of good mind", left everything to Seymour, only wishing her possessions "to be a thousand times more in value" than they were. Catherine, thirty-six years old, died on 5th September 1548, six days after the birth of her daughter.

On this day in 1877 Crazy Horse was invited to a meeting at Fort Robinson. While there he was bayoneted by a soldier named William Gentles. He died later that night.

Crazy Horse was born in about 1840. His father was a medicine man and his mother was the sister of Spotted Tail. A warrior of some distinction he fought with Red Cloud, leader of the Oglala Sioux, during the Indian Wars.

On 21st December, 1866, Captain W. J. Fetterman and an army column of 80 men, were involved in protecting a team taking wood to Fort Phil Kearny. Although under orders not to "engage or pursue Indians" Fetterman gave the orders to attack a group of Sioux warriors. The warriors ran away and drew the soldiers into a clearing surrounded by a much larger force. All the soldiers were killed in what became known as the Fetterman Massacre. Later that day the stripped and mutilated bodies of the soldiers were found by a patrol led by Captain Ten Eyck. Crazy Horse was one of those who took part in this massacre.

Crazy Horse and his men continued to attack soldiers trying to protect the Bozeman Trail. On 2nd August, 1867, several thousand Sioux and Cheyenne attacked a wood-cutting party led by Captain James W. Powell. The soldiers had recently been issued with Springfield rifles and this enabled them to inflict heavy casualties on the warriors. After a battle that lasted four and a half hours, the Native Americans withdrew. Six soldiers died during the fighting and Powell claimed that his men had killed about 60 warriors.

Despite this victory the army was unable to successfully protect the Bozeman Trail and on 4th November, 1868, Red Cloud and 125 chiefs were invited to Fort Laramie to discuss the conflict. As a result of these negotiations the American government withdrew the garrisons protecting the emigrants travelling along the trail to Montana. Red Cloud and his warriors then burnt down the forts.

In December, 1875 the Commissioner of Indian Affairs directed all Sioux bands to enter reservations by the end of January 1876. Sitting Bull, the spiritual leader of his people, refused to leave his hunting grounds. American Horse and Crazy Horse agreed and led his warriors north to join up with Sitting Bull.

In June 1876 Sitting Bull subjected himself to a sun dance. This ritual included fasting and self-torture. During the sun dance Sitting Bull saw a vision of a large number of white soldiers falling from the sky upside down. As a result of this vision he predicted that his people were about to enjoy a great victory.

On 17th June 1876, General George Crook and about 1,000 troops, supported by 300 Crow and Shoshone, fought against 1,500 members of the Sioux and Cheyenne tribes. The battle at Rosebud Creek lasted for over six hours. This was the first time that Native Americans had united together to fight in such large numbers.

General George A. Custer and 655 men were sent out to locate the villages of the Sioux and Cheyenne involved in the battle at Rosebud Creek. An encampment was discovered on the 25th June. It was estimated that it contained about 10,000 men, women and children. Custer assumed the numbers were much less than that and instead of waiting for the main army under General Alfred Terry to arrive, he decided to attack the encampment straight away.

Custer divided his men into three groups. Captain Frederick Benteen was ordered to explore a range of hills five miles from the village. Major Marcus Reno was to attack the encampment from the upper end whereas Custer decided to strike further downstream.

Reno soon discovered he was outnumbered and retreated to the river. He was later joined by Benteen and his men. Custer continued his attack but was easily defeated by about 4,000 warriors. At the battle of the Little Bighorn Custer and all his 264 men were killed. The soldiers under Reno and Benteen were also attacked and 47 of them were killed before they were rescued by the arrival of General Alfred Terry and his army.

The U.S. army now responded by increasing the number of the soldiers in the area. As a result Sitting Bull and his men fled to Canada, whereas Crazy Horse remained in Montana. He continued to lead attacks on settlers but on 22nd April, 1877, Crazy Horse and his followers, including his uncle, Little Hawk, surrendered to General George Crook at the Red Cloud Agency in Nebraska.

On this day in 1905 Arthur Koestler, the only child of Henrik Koestler (1869-1940), Jewish businessman, and Adele Zeiteles (1871–1963), was born in Budapest on 5th September, 1905. Koestler was close to his father but had a difficult relationship with his mother which lasted until her death.

In 1919 the Koestler family fled Hungary after a right-wing coup which deposed the ruling communists, and in 1922 Koestler began studying engineering and physics at the Vienna Technische Hochschule. Koestler became a Jewish nationalist and in 1925 left the university for a kibbutz in Palestine. According to his biographer, Kevin McCarron: "Koestler soon discovered that he was temperamentally unsuited to communal life. He moved to Tel Aviv, where he began to concentrate on journalism, publishing articles in Budapest's Pester Lloyd and in several Zionist papers. In 1927 he was employed by the Ullstein press as their correspondent in the Middle East. Koestler's journalistic work is considered by some to contain his best writing. As his reputation as a writer grew, so too did his disenchantment with Zionism. In 1929 he abruptly left Palestine for Ullstein's Paris office, and in 1930 he moved to Berlin to take up his new position as science editor."

Arthur Koestler was deeply concerned by the emergence of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party and in 1931 joined the German Communist Party. This resulted in him being sacked by Ullstein Verlag. The Communist International sent him to the Soviet Union to write about its first five-year plan. He travelled extensively through the USSR to research for the book but it was rejected by the Soviet authorities for containing too many criticisms of the communist system. Koestler now moved to Paris where he edited the weekly journal, Zukunft . On 22nd June 1935 he married Dorothea Ascher, a Communist Party worker.

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War he was sent by the party to spy on the Nationalist forces. Koestler posed as a right-wing Hungarian journalist working for the News Chronicle, but he came under suspicion and was arrested in Seville in February 1937. He was released the following year in an exchange of prisoners. Upon his release Koestler moved to England, where Victor Gollancz commissioned him to write a book about his experiences. Spanish Testament was published to considerable acclaim in 1937. In 1938 Koestler left the British Communist Party, because of the way Joseph Stalin was dealing with his critics in the Soviet Union.

In 1939 he published his first novel, The Gladiators (1939), a novel about the Spartacus slave revolt. However, he uses the story of Spartacus as an allegory for the corruption of socialism by Stalin. In September of that year Koestler was arrested in France, wrongly assumed to be a security risk, and was interned as a political prisoner in Le Vernet Concentration Camp until January 1940. His views on totalitarian rule appeared in his second novel, Darkness at Noon (1940). This was followed by The Scum of the Earth (1941), an account of his experiences of internment.

Koestler's biographer, Kevin McCarron, has argued: "Clearly influenced by his experiences in the condemned cells in Spain, Darkness at Noon (1940) describes the arrest and imprisonment of Rubashov, one of the early Bolsheviks, during the purges of 1936. During his numerous interrogations Rubashov reviews his career and his unthinking allegiance to communism. At the end of the novel, as he is beginning to doubt the party, he is shot in the back of the head. The novel was an immediate critical as well as commercial success. The novel became a weapon in the arsenal of the Cold War and remains one of the best-known and most widely read political novels of the twentieth century."

A. J. Ayer became one of Koestler's friends. In his autobiography Part of My Life (1977): Arthur Koestler had already published Darkness at Noon and Scum of the Earth, and I had read and admired them both.... Among other things, Darkness at Noon was the expression of Koestler's own disillusionment with the Communist party. The attraction which Soviet communism held in the middle nineteen-thirties had waned in England as a result of the Moscow trials and the Russian-German pact, but it was renewed with the entry of Russia into the war and increased with the success of Russian arms."

Koestler joined the British Army in 1941, but he had difficulty with military discipline and the following year he went to work for the Ministry of Information film unit and for the BBC, while beginning his third novel, Arrival and Departure (1943). In 1944 Koestler met Mamaine Paget, who was eleven years younger than him. By the end of the war Koestler had returned to his earlier Zionism and was a vocal advocate of the Jewish national cause. After a visit to Palestine he published Thieves in the Night (1946).

In 1948 Koestler became a British citizen. The following year he published The God That Failed (1949). It included an analysis of faith in politics and religion: "A faith is not acquired by reasoning. One does not fall in love with a woman, or enter the womb of a church, as a result of logical persuasion. Reason may defend an act of faith - but only after the act has been committed, and the man committed to the act. Persuasion may play a part in a man's conversion; but only the part of bringing to its full and conscious climax a process which has been maturing in regions where no persuasion can penetrate. A faith is not acquired; it grows like a tree. Its crown points to the sky; its roots grown downward into the past and are nourished by the dark sap of the ancestral humus."

Mamaine Paget became his second wife on 15th April 1950. They divorced in 1952 and she died aged 38 in 1954. In 1955 he had a daughter, Christine, with Janine Graetez, but he immediately disowned the girl. According to Kevin McCarron: "Koestler was short, handsome, and energetic, and attractive to women. He was, however, sexually predatory all his life - among other affairs he was the co-respondent named in Bertrand Russell's divorce from his third wife, Patricia Spence - and he was capable of treating women brutally.... A chain-smoker and heavy drinker, he could be arrogant, dogmatic, and violent, but he was financially generous, especially to continental intellectuals and refugees, and he was considered a welcoming host, and very lively, often too lively, company."

David Cesarani, the author of Arthur Koestler: The Homeless Mind (1998), has provided first-hand accounts of his violence towards women. Richard Brooks has argued that "Koestler was a compulsive adulterer who conducted hundreds of affairs throughout his marriages". His official biographer, Michael Scammell, the author of Koestler: The Indispensable Intellectual (2010) agreed with this view and accused him of "chronic promiscuity" and claims that Koestler's lovers included Simone de Beauvoir, Elizabeth Jane Howard and Sonia Brownell, who described him as a "sadist". Scammell quotes a letter written by Koestler where he argues “without an element of initial rape in seduction there is no delight”. However, Scammell raised doubts about an earlier claim made by Michael Foot that Koestler had raped his wife, Jill Craigie.

In 1951 he published his fourth novel, The Age of Longing. From 1952 to 1955 he worked on two volumes of autobiography: Arrival and Departure (1952) and The Invisible Writing (1954). According to one critic: "Lucid, analytical, yet emotional, Koestler depicts himself in his autobiographical writings as both a unique human being and a representative, universal voice of the twentieth century." Other books by Koestler during this period included Reflections on Hanging (1956), The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe (1959) and Hanged By the Neck (1961).

On 8th January 1965, the sixty-year-old, Koestler, married the thirty-seven year old, Cynthia Jefferies, who had been his secretary and occasional lover since 1948. He continued to write and published The Ghost in the Machine (1967), The Case of the Midwife Toad (1971), The Call Girls (1972), The Roots of Coincidence (1972) and Life After Death (1976).

In 1976 Koestler was diagnosed as having Parkinson's disease and his health deteriorated over the next seven years, during which he also succumbed to terminal leukaemia. He wrote in his suicide note: "My reasons for deciding to put an end to my life are simple and compelling: Parkinson's Disease and the slow-killing variety of leukaemia (CCI). I kept the latter a secret even from intimate friends to save them distress. After a more or less steady physical decline over the last years, the process has now reached an acute state with added complications which make it advisable to seek self-deliverance now, before I become incapable of making the necessary arrangements... What makes it nevertheless hard to take this final step is the reflection of the pain it is bound to inflict on my surviving friends, above all my wife Cynthia. It is to her that I owe the relative peace and happiness that I enjoyed in the last period of my life - and never before."

Michael Scammell has argued that Koestler had a “sadomasochistic” relationship with his wife and despite being in perfect health agreed to commit suicide with her husband. She wrote in a note: “I fear both death and the act of dying... Double suicide has never appealed to me, but now Arthur’s incurable diseases have reached a stage where there is nothing else to do.” Scammell sees his wish for her to die with him as evidence of his selfishness.

On 3rd March 1983, Arthur Koestler and Cynthia Koestler were found dead in their flat at 8 Montpelier Square, Kensington, London. They had killed themselves with a mixture of tuinal and alcohol. Koestler left bequests which totalled almost £1 million to further the study of parapsychology.

On this day in 1906 David Lloyd George makes speech explaining why the Liberal Party needs to adopt left-wing policies. He warned that if the government did not pass progressive measures, at the next election, the working-class would vote for the Labour Party: "If at the end of our term of office it were found that the present Parliament had done nothing to cope seriously with the social condition of the people, to remove the national degradation of slums and widespread poverty and destitution in a land glittering with wealth, if they do not provide an honourable sustenance for deserving old age, if they tamely allow the House of Lords to extract all virtue out of their bills, so that when the Liberal statute book is produced it is simply a bundle of sapless legislative faggots fit only for the fire - then a new cry will arise for a land with a new party, and many of us will join in that cry."

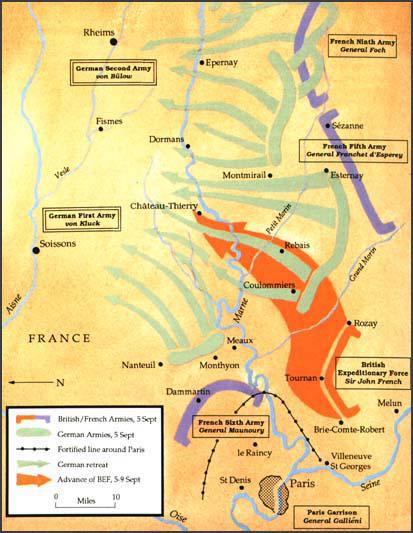

On this day in 1914 the Battle of the Marne begins. At the end of August 1914, the three armies of the German invasion's northern wing were sweeping south towards Paris. The French 5th and 6th Armies and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) were in retreat. General Alexander von Kluck, commander of the German Ist Army, was ordered to encircle Paris from the east. Expecting the German army to capture Paris, the French government departed for Bordeaux. About 500,000 French civilians also left Paris by the 3rd September.

Joseph Joffre, the Commander-in-Chief of the French forces, ordered his men to retreat to a line along the River Seine, south-east of Paris and over 60km south of the Marne. Joffre planned to attack the German Ist Army on 6th September and decided to replace General Charles Lanrezac, the commander of the 5th Army, with the more aggressive, General Franchet D'Esperey. The commander of the BEF,Sir John French, agreed to join the attack on the German forces.

General Michel Maunoury and the French 6th Army attacked the German Ist Army on the morning of 6th September. General von Kluck wheeled his entire force to meet the attack, opening a 50km gap between his own forces and the German 2nd Army led by General Karl von Bulow. The British forces and the French 5th now advanced into the gap that had been created splitting the two German armies.

For the next three days the German forces were unable to break through the Allied lines. At one stage the French 6th Army came close to defeat and were only saved by the use of Paris taxis to rush 6,000 reserve troops to the front line. On 9th September General Helmuth von Moltke, the German Commander in Chief, ordered General Karl von Bulow and General Alexander von Kluck to retreat. The British and French forces were now able to cross the Marne. Despite encountering little opposition, the advance was slow and the armies covered less than twelve miles on that first day. This enabled Kluck's Ist Army to reunite with Bulow's forces at the River Aisne.

By the evening of 10th September, the Battle of the Marne was over. During the battle, the French had around 250,000 casualties. Although the Germans never published the figures, it is believed that Geman losses were similar to those of France. The British Expeditionary Force lost 12,733 men during the battle.

The most important consequence of the Battle of the Marne was that the French and British forces were able to prevent the German plan for a swift and decisive victory. However, the German Army was not beaten and its successful retreat ended all hope of a short war.

On this day in 1945 Igor Gouzenko defects to Canada, exposing Soviet espionage in North America. Gouzenko was born in Rogachovo, Russia on 13th January, 1922. He worked as a cipher clerk at the Soviet Military Intelligence (GRU) in Moscow. "I had a desk in what had been the ballroom of a pre-revolutionary mansion. There were about 40 of us at a time working in three shifts."

Gouzenko joined the Russian Legation in Ottawa, Canada in 1943. This was only a cover as he was really a KGB intelligence officer. According to Benjamin de Forest Bayly: "The military attaché at the Soviet embassy got Gouzenko to decode one of his messages because he didn't feel like doing it himself. When Gouzenko decoded it he saw it was instructions for him to be sent back to the Soviet Union, because he wasn't trusted." His wife advised him to: "Go into the vault and steal every secret thing you can put your hands on, and change the combination on the vault and lock the door. It'll take six weeks for the Russians to send somebody over to chisel the door of the safe open to find out you've taken all these things. Turn yourself over to the Canadians."

Over the next few weeks he started taking home secret documents. Gouzenko left the Soviet embassy on 5th September, 1945. He later wrote: "There were almost a hundred documents, some of them small scraps of paper and others covering several large sheets of stationary... The documents felt like they weighed a ton and I imagined that they were bulging out from under my shirt." The following day he went to the Justice Department. However, he was turned away and he decided to take his story to Ottawa Journal. With their help he was interviewed by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).

The next morning Norman Robertson, Undersecretary of State for External Affairs, had a meeting with Prime Minister Mackenzie King. He explained that Gouzenko had claimed that he had documents showing that the Soviets had spies in Canada and the United States and that "some of these men were around" Edward Stettinius, the U.S. Secretary of State. King wrote in his diary that "Robertson seemed to feel that the information might be so important both to the States... and to Britain that it would be in their interests to seize it no matter how it was obtained." King was worried that taking these documents might cause political problems in the future. "I said to Robinson... that I thought we should be extremely careful in becoming a party to any course of action which would link the government of Canada up with this matter in a manner which might cause Russia to feel that we had performed an unfriendly act. That to seek to gather information in any underhand way would make clear that we did not trust the Embassy... My own feeling is that the individual has incurred the displeasure of the Embassy and is really seeking to shield himself."

Amy W. Knight, the author of How the Cold War Began (2005), has pointed out: "King would later be criticized for not immediately grasping the importance of what the defector had to offer and for his naivety in trusting the Soviets. But his reaction was understandable. Apart from wishing to avoid a diplomatic debacle, King also questioned the motives of the potential defector. The man was quite possibly lying to save his own skin, or because he wanted to live in Canada and needed a means to gain asylum. Whatever the case, King was not about to allow a Soviet code clerk to disrupt the cordial diplomacy that had characterized Ottawa's relations with Moscow."

It was later pointed out that William Stephenson, the head of British Security Coordination, was involved in Gouzenko's defection. He "argued strongly against King's view that Gouzenko should be ignored. The Russian, he said, would certainly have information valuable not merely to Canada but also to Britain, the United States, and other Allies. Furthermore, Gouzenko's life was almost certainly in danger. They should act, and do so immediately, by taking Gouzenko in."

Stephenson arranged for Gouzenko to be taken into protective custody. He was then transferred to Camp X, where he and his wife lived in guarded seclusion. Later two former BSC agents interviewed him. He claiming he had evidence of an Soviet spy ring in Canada. Gouzenko provided evidence that led to the arrest of 22 local agents and 15 Soviet spies in Canada. This included Agatha Chapman, Fred Rose, Sam Carr, Raymond Boyer, Edward Mazerall, Gordon Lunan, and Kathleen Willsher. Information from Gouzenko also resulted in the arrest and conviction of Klaus Fuchs and Allan Nunn May.

The case was passed on to Kim Philby, head of Section IX (Soviet Affairs) of MI6. Philby later recalled: "The first information about Gouzenko and Elli came from Stephenson. "C" (Stewart menzies) called me in and asked me my opinion about it. I said Gouzenko's defection was obviously very important and we treated it as such. But it was a disaster for the KGB and there was no way I could help. The Mounties had Gouzenko so well protected that it was impossible for the Russians to do anything about him, bump him off or anything like that. So he was able to give away a big Canadian network, and the telegrams he brought with him when he defected would have been of great help to Western decrypters."

By 17th September Philby was reporting what Gouzenko was telling BSC. "Stanley (Philby) reports that he managed to learn details of the information turned over to Canada by the traitor Gouzenko... As a result of these affairs the British intelligence and counter-intelligence organs are undoubtedly going to take effective measures soon against illegal activity by fraternal and Soviet intelligence."

Philby was expected to go to Canada but instead he sent Roger Hollis. It has been argued by Ben Macintyre, the author of A Spy Among Friends (2014), the reason for this was that he feared Gouzenko was about to expose him as a Soviet spy. "He (Philby) waited anxiously for the results of Gouzenko's debriefing. Philby may have contemplated defection to the Soviet Union. The defector exposed a major spy network in Canada, and revealed that the Soviets had obtained information about the atomic bomb project from a spy working at the Anglo-Canadian nuclear research laboratory in Montreal. But Gouzenko worked for the GRU, Soviet military intelligence, not the NKVD; he knew little about Soviet espionage in Britain."

Igor Gouzenko told the investigators that when he was working in Moscow he discovered that the GRU had an important spy based in London with the code name "Elli". Apparently Elli's information was considered so important that as soon as the information came in from him it was taken immediately to Joseph Stalin. Gouzenko told Chapman Pincher: "I sat next to my friend Lieutenant Luibimov and one day he passed me a telegram he had deciphered from the Soviet Embassy in London. He said it came from a spy right inside British counter-intelligence in England. The spy's code-name in the secret radio traffic between London and Moscow was Elli." Gouzenko also claimed that when it was decided to send the senior MI5 officer, Guy Liddell to Ottawa in 1944 to discuss security issues with Canadian Intelligence, this information was leaked by someone based in London.

A report written in September 1945 stated that "(Gouzenko) states that while he was in the Central Code Section in Moscow in 1942... he heard about a Soviet agent in England, allegedly a member of the British Intelligence Service. This agent, who was of Russian descent, had reported that the British had a very important agent of their own in the Soviet Union, who was apparently being run by someone in Moscow... When the message arrived it was received by a Lt. Col. Polakova who, in view of its importance, immediately got in touch with Stalin himself by telephone."

Gouzenko and his family were given another identity by the Canadian government out of fear of Soviet reprisals. He later wrote about the reasons why he defected: "During my residence in Canada, I have seen how the Canadian people and their government, sincerely wishing to help the Soviet people sent supplies to the Soviet Union, collected money for the welfare of the Russian people, sacrificing the lives of their sons in the delivery of supplies across the ocean - and instead of gratitude for the help rendered, the Soviet government is developing espionage activity in Canada, preparing to deliver a stab in the back to Canada - all this without the knowledge of the Russian people."

Gouzenko was given a house and two acres of land in Port Credit, Ontario, a small lakeside town west of Toronto. The Canadian government provided them with a new identity and cover stories that accounted for their thickly accented English. They were now Czech immigrants, Stanley and Anna Krysac. They also a RCMP guard living with them. However, the Canadian security services still feared that the Soviets would find a way to assassinate him. The RCMP Commissioner Stuart Wood wrote to the Minister of Justice in October 1947, complaining that "Gouzenko's disregard for advice and the manner in which he persisted in doing things his own way, regardless of security, were bound to expose him within a short period of time."

Gouzenko began work with two journalists on an account of his defection. The book, This Was My Choice, appeared in 1949. However, he was not allowed to give any details of the information that he had given to Western intelligence agencies. The book did not sell well but it ended up being profitable because it was made into a movie, The Iron Curtain (1948). According to John Sawatsky, the author of Gouzenko: The Untold Story (1984) Gouzenko fell-out with most of his guards. He quoted one guard as saying: "Gouzenko was not a true lover of liberty. He was a thoroughly ignorant Russian peasant who had no connection with the Russian Intelligence Service except as a cipher clerk. I have known him for some time and feel he is an unsavory character." Gouzenko also came into conflict with George McClellan, the head of the RCMP Special Branch. When he threatened to withdraw protection he was accused of being a Soviet spy.

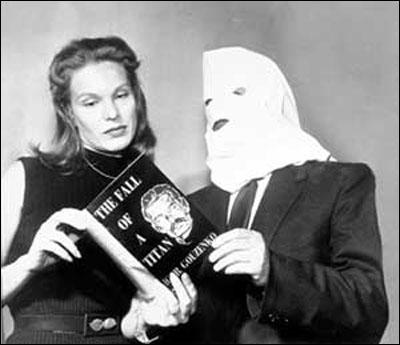

In January 1954 Gouzenko was interviewed by Drew Pearson on television. He wore a pillowcase over his head so that he could not be identified. Gouzenko also appeared in public, wearing a hood, to promote his novel, The Fall of a Titan (1954), about life in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. The book was a huge success and was translated into more than forty languages. The Toronto Daily Star described it as a "panoramic novel... Tolstoyan in its sweep".

Granville Hicks argued in the New York Times: "Involved as the story is, the reader never loses its thread, but goes on, always more and more absorbed, to the explosive climax.... It is Mr. Gouzenko's ability to create this atmosphere - the anguish of the masses, the ruthlessness of the privileged few, the universal terror - that gives his book its overwhelming plausibility." Another critic described it as the work of a "young genius". The Fall of a Titan won the Governor-General of Canada's Prize for Literature in 1954.

Igor Gouzenko was interviewed by Tania Long of the New York Times in December 1954. He told Long that he wanted, above all, to be a good writer: "My immediate ambition you might say is to write my next book in half the time I took on my first. I think I have learned a lot, and what is most important is that I now have confidence in myself. Can you imagine how it was for four years, writing away day after day, with the feeling that maybe I was completely wrong and no one to encourage me?" Gouzenko spent over twenty-five years on his next novel. According to his wife, he produced enough pages to fill three books. However, he never sent it to a publisher because he considered it unfinished.

According to Amy W. Knight, the author of How the Cold War Began (2005): "In addition to acting as her husband's secretary, copyist, and chauffeur, Anna gave birth to eight children, made all their clothes, ran the household (or tried to), and engaged in several entrepreneurial ventures, none of which, including the purchase of the farm and some butcher shops, proved profitable." In 1962, the Canadian government awarded the Gouzenkos a pension of five hundred dollars a month.

Gouzenko did not like being called a defector. It implied that he was a traitor. Instead, he insisted, he should be called an "escaper". When Newsweek referred to him as a defector in February 1964, he contacted a lawyer. He also disliked the suggestion in the article that defectors were psychologically troubled. Gouzenko refused to settle when the magazine offered him one thousand dollars in damages and he ended up getting nothing. However, he was successful in obtaining $750 from Mclean's Magazine. Another successful libel suit was against David Martin, the author of Wilderness of Mirrors. He objected to Martin questioning his motives for defecting. Gouzenko received $10,000 in damages.

In 1972 Gouzenko was re interviewed by MI5. He later told the journalist, Chapman Pincher: "Stewart was stationed in Washington and asked to see me at the Royal York Hotel in Toronto. He read me a long report - several typed sheets - paragraph by paragraph. I was astonished to learn that this was the report submitted by the man, who could only have been Hollis, because I could not understand how he had written so much when he had asked me so little. I soon discovered why because the report was full of nonsense and lies. For instance, he reported me as telling him that I knew, in 1945, that there was a spy working for Britain in a high-level Government office in Moscow. I knew no such thing and had said nothing like that."

Igor Gouzenko concluded that Roger Hollis must have been a Soviet spy: "As Stewart read the report to me it became clear that it had been faked to destroy my credibility so that my information about the spy in MI5 called 'Elli' could be ignored. If the report was written by Hollis then there is no doubt that he was a spy. I suspect that Hollis himself was 'Elli' and he may have feared that I might recognize him if I had seen a photograph of him in the files in Moscow but as a cypher-clerk I had no opportunity to see photographs."

Igor Gouzenko developed diabetes and started to go blind and eventually he lost his sight completely. He then wrote on a braille typewriter or dictated the novel to Anna. He died at Mississauga on 25th June, 1982.

On this day in 1982 Douglas Bader died.

Bader, the son of a soldier who died as a result of the wounds suffered in the First World War, was born in London ion 21st February, 1910. A good student, Bader won a scholarship to St Edward's School in Oxford. An excellent sportsman, Bader won a place to the RAF College in Cranwell where he captained the Rugby team and was a champion boxer.

Bader was commissioned as an officer in the Royal Air Force in 1930 but after only 18 months he crashed his aircraft and as a result of the accident had to have both legs amputated.

Discharged from the RAF he found work with the Asiatic Petroleum Company. On the outbreak of the Second World War was allowed to rejoin the RAF.

A member of 222 Squadron, Bader, flying a Hawker Hurricane, he took part in the operation over Dunkirk and showed his ability by bringing down a Messerschmitt Bf109 and a Heinkel He111.

Douglas Bader was now promoted by Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory and was given command of 242 Squadron, which had suffered 50 per cent casualties in just a couple of weeks. Determined to raise morale, Bader made dramatic changes to the organization. This upset those in authority and was ordered to appear before Hugh Dowding, the head of Fighter Command.

The squadron's first sortie during the Battle of Britain on 30th August, 1940, resulted in the shooting down of 12 German aircraft over the Channel in just over an hour. Bader himself was responsible for downing two Messerschmitt 110.

Bader had strong ideas on tactics and did not always follow orders. He took the view that RAF fighters should be sent out to meet the German planes before they reached Britain. Hugh Dowding rejected this strategy as he believed it would take too long to organise.

Air Vice Marshal Keith Park, the commander of No. 11 Fighter Group, also complained complained that Bader's squadron should have done more to protect the air bases in his area instead of going off hunting for German aircraft to shoot down.

When William Sholto Douglas became head of Fighter Command, he developed what became known as the Big Wing strategy. This involved large formations of fighter aircraft deployed in mass sweeps against the Luftwaffe over the English Channel and northern Europe. Although RAF pilots were able to bring down a large number of German aircraft, critics claimed that they were not always available during emergencies and prime targets became more vulnerable to bombing attacks.

This strategy suited Bader and during the summer of 1941 he obtained 12 kills. His 23 victories made him the fifth highest ace in the RAF. However, on 9th August 1941, he suffered a mid-air collision down near Le Touquet, France. He parachuted to the ground but both his artificial legs were badly damaged.

Bader was taken to a hospital and with the help of a French nurse managed to escape. He reached the home of a local farmer but was soon arrested and sent to a prison camp. After several attempts to escape he was sent to Colditz.

Bader was freed at the end of the Second World War and when he returned to Britain he was promoted to group captain. He left the Royal Air Force in 1946 and became managing director of Shell Aircraft until 1969 when he left to become a member of the Civil Aviation Authority Board.

On this day in 1997 the Spartacus Educational website was established. The last time we counted (October, 2019), the Spartacus Educational website contained 21,036,905 words and 33,196 sources. Spartacus Educational is committed to producing free content, especially to those countries that find it difficult to purchase books, but we need your help. There are several things you could do for us. (1) Do not use ad-blocker. (2) Share our pages via Twitter, Facebook, etc. (3) Make a small donation or a small monthly subscription.