On this day on 6th September

On this day in 1795 Fanny Wright was born in Dundee. Both her father, a wealthy Scottish linin manufacturer, and her mother died by the time she was three years old. Wright was brought up in the homes of relatives, including James Milne, a member of Scottish school of progressive philosophers. Milne, who encouraged Fanny to question conventional ideas, was to have a lasting influence on her political development.

Wright visited the USA in 1818 and after returning to England published her observations of the country in her book, Views of Society and Manners in America (1821). The book praised America's experiments in democracy and provided information for those radicals in Britain involved in the struggle for parliamentary reform.

In England she became friendly with the Marquis de Lafayette and together they returned to the United States in 1824. Later that year Wright visited New Harmony in Indiana, the socialist community established by Robert Owen and his son Robert Dale Owen. She was immediately converted to Owenism and decided to form her own co-operative community.

In 1825 Wright purchased 2,000 acres of woodland thirteen miles from Memphis in Tennessee and formed a community called Nashoba. Wright then bought slaves from neighbouring farmers, freed them, and gave them land on her settlement.

Some aspects of Wright's community were extremely controversial, especially her decision to encourage sexual freedom. She came to believe that miscegenation was the ultimate solution of the racial question. Wright saw marriage as a discriminatory institution and started advocating free love.

Wright also developed her own dress code for women. This included bodices, ankle-length pantaloons and a dress cut to above the knee. This style was later promoted by feminists such as Amelia Bloomer, Susan Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Wright spent her entire personal fortune on her Nashoba co-operative community. She hoped it would become economically self-sufficient but this did not happen and in 1828 she was forced to abandon her experiment. Wright and Robert Dale Owen arranged for the former slaves to be sent to the black republic of Haiti.

In 1829 Wright settled in New York where she published her book, Course of Popular Lectures. She also combined with Robert Dale Owen to publish the Free Enquirer. In the journal Wright advocated socialism, the abolition of slavery, universal suffrage, free secular education, birth control, changes in the marriage and divorce laws. Wright and Owen also became involved in the radical Workingmen's Party while living in New York.

Fanny Wright married the French doctor, Guillaume P. Darusmont in 1831. The marriage was not a success and ended in divorce. As her husband, Darusmont had managed to gain control over her entire property, including her earnings from lectures and the royalties from her books. Fanny Wright was in the middle of a legal struggle with Darusmont, when she died on 13th December, 1852. As requested, her tombstone in Cincinnati was inscribed with the words: "I have wedded the cause of human improvement, staked on it my fortune, my reputation and my life."

On this day in 1860 Jane Addams, the eighth child of a successful businessman, was born in Cedarville, Illinois. Jane's mother died when she was only three years old but she was deeply influenced by her father who was a Quaker but had supported Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War.

According to Harriet Hyman Alonso: "Jane Addams was greatly influenced by her father, who stood out in the community as a great supporter of Abraham. Lincoln and an opponent of slavery and was a God-fearing man who, his daughter claimed, favored Quakerism although regularly attending services in both Methodist and Presbyterian churches. Addams, therefore, was reared in a religious home that valued humanitarianism. As a girl, she expressed sympathy for former slaves and other impoverished people in the community. As many other children whose parents opposed slavery but supported the Civil War, Addams grew up aware of the dilemma between fighting a just war and maintaining moral witness against all violence. These values made her a perfect candidate for a lifetime of work around social justice issues."

Edmund Wilson claimed that: "A little girl with curvature of the spine, whose mother had died when she was a baby, she abjectly admired her father, a man of consequence in frontier Illinois, a friend of Lincoln and a member of the state legislature, who had a floor mill and a lumber mill on his place. Whenever there were strangers at Sunday school, she would try to walk out with her uncle so that her father should not be disgraced by people's knowing that such a fine man had a daughter with a crooked spine."

Jane Addams graduated from Rockford Female Seminary in 1881. She then attended the Women's Medical College in Philadelphia, but was forced to abandon her studies after undergoing a serious spinal operation. Eleanor J. Stebner, the author of The Women of Hull House (1997), has argued: "For the next seven years, Addams struggled to find her voice and a way to take an active part in the world she encountered."

In 1888, while on a European tour, Jane Addams and Ellen Starr, visited the university settlement, Toynbee Hall in the East End of London. Named after the social reformer, Arnold Toynbee, the settlement was run by Samuel Augustus Barnett, canon of St. Jude's Church. Situated in Commercial Street, Whitechapel, Toynbee Hall was Britain's first university settlement. The idea was to create a place where students from Oxford University and Cambridge University could work among, and improve the lives of the poor during their summer holidays. The settlement also served as a base for Charles Booth and his group of researchers working on the Life and Labour of the People in London.

When Jane Addams and Ellen Starr returned to Chicago in 1889, they decided to start a similar project in Chicago. Helen Culver agreed to rent them Hull House for $60 a month. This large, abandoned mansion had been built by the wealthy businessman, Charles J. Hull, in 1856. Situated in Halstead Street, most of the people living in the area were recently arrived immigrants from Italy and Germany.

Jane Addams and Ellen Starr moved in to Hull House on 18th September, 1889. They began by inviting people living in the area to hear reading of George Eliot's Romola and to look at slides of Florentine art. After talking to the people who visited the house, it soon became clear that the women had a desperate need for a place where they could bring their young children. Addams and Starr decided to start a kindergarten and provide a room where the mothers could sit and talk. Jenny Dow, who lived in an expensive part of Chicago, agreed to come to Hull House to run the nursery school. Within three weeks the kindergarten had enrolled twenty-four children with 70 more on the waiting list.

Other activities soon followed. Jane Addams ran a club for teenage boys. Whereas Ellen Starr provided lessons in cooking and sewing for young girls. Local university teachers and students were also recruited to provide free lectures on a wide variety of different topics.

Inspired by the ideas of William Morris and John Ruskin, the women decided to turn Hull House into an art gallery. While in Europe the two women had collected reproductions of paintings and these were now hung in the various rooms of the house. Ellen Starr organized art classes and exhibitions as well as developing a scheme where people could borrow art reproductions to hang in their own homes.

Italian and German evenings were also organized at Hull House. Local people presented songs, dances, games and food associated with the countries from where they used to live. This was probably the most successful of their early ventures as it provided an opportunity for local people to make their own contribution to the venture. As Addams later recalled, it soon became clear that the object of the settlement program should be to "help the foreign-born conserve and keep whatever of value their past life contained and to bring them into contact with a better class of Americans."

In 1890 Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr were joined at Hull House by Julia Lathrop. All three women had been students at Rockford Seminary together in the 1980s. Lathrop, who had been trained as a lawyer by her father, the United States senator, William Lathrop, was an excellent organizer, and took over the day to day running of the settlement.

Jane Addams, Ellen Gates Starr and Julia Lathrop gradually became more involved in the community where they were living. They were shocked by the poor housing, the overcrowding and the poverty that the people were having to endure. Addams wrote to her step-brother that she was "overpowered by the misery and narrow lives" of these people.

In the early days of Hull House, the three women were influenced by the Christian Socialism that had inspired the creation of Toynbee Hall. This was reinforced by the arrival in 1891 of Florence Kelley at Hull House. A member of the Socialist Labor Party, Kelley had considerable experience of political and trade union activity. It was Kelley who was mainly responsible for turning Hull House into a centre of social reform.

The presence of Florence Kelley in Hull House attracted other social reformers to the settlement. This included Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Alice Hamilton, Mary McDowell, Charles Beard, Mary Kenney, Charlotte Perkins, Alzina Stevens and Sophonisba Breckinridge. Working-class women, such as Kenney and Stevens, who had developed an interest in social reform as a result of their trade union work, played an important role in the education of the middle-class residents at Hull House. They in turn influenced the working-class women. As Kenney was later to say, they "gave my life new meaning and hope".

Addams met Mary White Ovington, the founder of the Greenpoint Settlement in Brooklyn. Ovington remembers Addams telling her: "If you want to be surrounded by second-rate ability, you will dominate your settlement. If you want the best ability, you must allow great liberty of action among your residents."

Florence Kelley and several other women based at Hull House carried out research into the sweating trade in Chicago and this led to the passing of the pioneering Illinois Factory Act (1893). Kelley was recruited by the state's new governor, John Peter Altgeld, as the chief factory inspector, and two other women involved in the research, Alzina Stevens and Mary Kenney, became inspectors in Illinois.

Helen Culver, who owned Hull House, also gave the women other adjacent property. Wealthy people in Chicago contributed money, including Louise Bowen who provided three quarters of a million dollars. This enabled the group to expand its activities. An art gallery was added in 1891, a coffee house and gymnasium in 1893, a club house in 1898 and a theatre in 1899.

In 1903 several women associated with Hull House, including Jane Addams, Mary Kenney, Mary McDowell, Florence Kelley and Sophonisba Breckinridge, were involved in establishing the Women's Trade Union League. Union meetings were often held at Hull House and members of the settlement helped support workers during industrial disputes. This resulted in some wealthy people withdrawing their support for Hull House. One businessman wrote that Hill House had "been so thoroughly unionized that it has lost its usefulness and has become a detriment and harm to the community as a whole."

The Hull House complex was not completed until 1907. The settlement now had thirteen buildings spread over a large city block. There were around 70 people living in Hull House and it cost the settlement over $26,500 to run the house and its programs. Rents and sales raised $12,000 but the rest had to come from donations.

On 3rd September 1908, William English Walling published his article, Race War in the North. Walling complained that "a large part of the white population" in the area were waging "permanent warfare with the Negro race". He quoted a local newspaper as saying: "It was not the fact of the whites' hatred toward the negroes, but of the negroes' own misconduct, general inferiority or unfitness for free institutions that were at fault." Walling argued that they only way to reduce this conflict was "to treat the Negro on a plane of absolute political and social equality".

Walling argued that the people behind the riots were seeking economic benefits: "If the white laborers get the Negro laborers' jobs; if masters of Negro servants are able to keep them under the discipline of terror as I saw them doing in Springfield; if white shopkeepers and saloon keepers get their colored rivals' trade; if the farmers of neighboring towns establish permanently their right to drive poor people out of their community, instead of offering them reasonable alms; if white miners can force their negro fellow-workers out and get their positions by closing the mines, then every community indulging in an outburst of race hatred will be assured of a great and certain financial reward, and all the lies, ignorance and brutality on which race hatred is based will spread over the land."

Walling suggested that racists were in danger of destroying democracy in the United States: "The day these methods become general in the North every hope of political democracy will be dead, other weaker races and classes will be persecuted in the North as in the South, public education will undergo an eclipse, and American civilization will await either a rapid degeneration or another profounder and more revolutionary civil war, which shall obliterate not only the remains of slavery but all other obstacles to a free democratic evolution that have grown up in its wake. Yet who realizes the seriousness of the situation, and what large and powerful body of citizens is ready to come to their aid.

Mary Ovington, a journalist working for the New York Evening Post, responded to the article by writing to Walling and inviting him and a few friends to her apartment on West Thirty-Eighth Street. Ovington was impressed with Walling: "It always seemed to me that William English Walling looked like a Kentuckian, tall, slender; and though he might be talking the most radical socialism, he talked it with the air of an aristocrat."

They decided to form the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). The first meeting of the NAACP was held on 12th February, 1909. Early members included Jane Addams, William English Walling, Anna Strunsky, Mary Ovington, Josephine Ruffin, Mary Talbert, Lillian Wald, Florence Kelley, Mary Church Terrell, Inez Milholland, George Henry White, William Du Bois, Charles Edward Russell, John Dewey, Charles Darrow, Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, William Dean Howells, Fanny Garrison Villard, Oswald Garrison Villard and Ida Wells-Barnett.

A strong supporter of women's suffrage, Addams was vice-president of the National American Women's Suffrage Association (1911-14). Addams controversially supported Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Party in the 1912 presidential elections. Some of the her friends were highly critical of his aggressive foreign policy and his unwillingness to openly support African American civil rights.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Jane Addams and a group of women pacifists in the United States, began talking about the need to form an organization to help bring it to an end. On the 10th January, 1915, over 3,000 women attended a meeting in the ballroom of the New Willard Hotel in Washington and formed the Woman's Peace Party. Addams was elected chairman and other women involved in the organization included Mary McDowell, Florence Kelley, Alice Hamilton, Anna Howard Shaw, Belle La Follette, Fanny Garrison Villard, Emily Balch, Jeanette Rankin, Lillian Wald, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Mary Heaton Vorse, Freda Kirchwey, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Crystal Eastman, Carrie Chapman Catt and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

In April 1915, Arletta Jacobs, a suffragist in Holland, invited members of the Woman's Peace Party to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Addams was asked to chair the meeting and Alice Hamilton, Mary Heaton Vorse, Julia Lathrop, Leonora O'Reilly, Sophonisba Breckinridge, Grace Abbott and Emily Bach went as delegates from the United States. Others who went to the Hague included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse, (England); Chrystal Macmillan (Scotland) and Rosika Schwimmer (Hungary). Afterwards, Addams, Jacobs, Macmillan, Schwimmer and Balch went to to London, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Rome and Paris to speak with members of the various governments in Europe. During this time they met Edward Grey (13th May), Herbert Asquith (14th May), Gottlieb von Jagow (21st May), Theobold von Bethmann-Hollweg (22nd May), Karl von Sturgkh (26th May), Théophile Delcassé (12th June) and Rene Viviani (14th June).

The women were attacked in the press by Theodore Roosevelt who described them as "hysterical pacifists" and called their proposals "both silly and base". Addams was selected for particular criticism. One man wrote in the Rochester Herald, "In the true sense of the word, she is apparently without education. She knows no more of the discipline and methods of modern warfare than she does of its meaning. If the woman conceded by her sisters to be the ablest of her sex, is so readily duped, so little informed, men wonder what degree of intelligence is to be secured by adding the female vote to the electorate."

Henry Ford, the wealthy American businessman, soon made it clear he opposed the war and supported the decision of the Woman's Peace Party to organize a peace conference in Holland. After the conference Addams, Oswald Garrison Villard, and Paul Kellogg, met with Ford and suggested he should sponsor an international conference in Stockholm to discuss ways that the conflict could be brought to an end. During this period Theodore Roosevelt described Addams as "the most dangerous woman in America."

Henry Ford came up with the idea of sending a boat of pacifists to Europe to see if they could negotiate an agreement that would end the war. He chartered the ship Oskar II, and it sailed from Hoboken, New Jersey on 4th December, 1915. Addams planned to be on the ship but three days before it was due to leave she became seriously ill with tuberculosis of the kidneys. The Ford Peace Ship reached Stockholm in January, 1916, and a conference was organized with representatives from Denmark, Holland, Norway, Sweden and the United States. However, unable to persuade representatives from the warring nations to take part, the conference was unable to negotiate an Armistice.

In 1918 Herbert Hoover recruited Addams to his Department of Food Administration. She toured the country making speeches encouraging the people of America to help conserve and increase production of food. This upset some pacifists who felt that any support of the war effort was morally wrong. However, she was praised by some of her former critics. The editor of the Los Angeles Times wrote: "now she is seeing clearly again, and her service is with the country, with the administration, with the Allies, wholehearted and whole-souled."

Addams was again criticised in April 1919 when she lead the American delegation to the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) conference in Zurich. Among the delegates were Florence Kelley, Alice Hamilton, Emily Balch, Jeanette Rankin and Lillian Wald. At the conference Addams was elected president of the WILPF and Balch became secretary-treasurer.

In 1919 Woodrow Wilson appointed A. Mitchell Palmer as his attorney general. Palmer had previously been associated with the progressive wing of the party and had supported women's suffrage and trade union rights. However, once in power, Palmer's views on civil rights changed dramatically. Worried by the revolution that had taken place in Russia, Palmer became convinced that Communist agents were planning to overthrow the American government. Palmer recruited John Edgar Hoover as his special assistant and together they used the Espionage Act (1917) and the Sedition Act (1918) to launch a campaign against radicals and left-wing organizations.

On 7th November, 1919, the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, over 10,000 suspected communists and anarchists were arrested in what became known as the Palmer Raids. Palmer and Hoover found no evidence of a proposed revolution but large number of these suspects were held without trial for a long time. The vast majority were eventually released but Emma Goldman and 247 other people, were deported to Russia.

In January, 1920, another 6,000 were arrested and held without trial. Palmer and Hoover found no evidence of a proposed revolution but a large number of these suspects, many of them members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), continued to be held without trial. When Palmer announced that the communist revolution was likely to take place on 1st May, mass panic took place. In New York, five elected Socialists were expelled from the legislature.

Jane Addams was appalled by the way people were being persecuted for their political beliefs and in 1920 joined with Roger Baldwin, Norman Thomas, Chrystal Eastman, Paul Kellogg, Clarence Darrow, John Dewey, Abraham Muste, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Upton Sinclair to form the American Civil Liberties Union.

During her life Jane Addams wrote articles about social problems in a variety of magazines including American Magazine, McClures, Crisis, and Ladies Home Journal. Addams also wrote several books including, Democracy and Social Ethics (1902), Newer Ideals of Peace (1907), Spirit of Youth (1909), Twenty Years at Hull House (1910), A New Conscience and an Ancient Evil (1912), Peace and Bread in Time of War (1922) and The Second Twenty Years at Hull House (1930).

In 1927 Jane Addams joined with John Dos Passos, Alice Hamilton, Jane Addams, Upton Sinclair, Dorothy Parker, Ben Shahn, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Floyd Dell, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells in an effort to prevent the execution of Nicola Sacco and Bertolomeo Vanzetti. Although Webster Thayer, the original judge, was officially criticised for his conduct at the trial, the execution went ahead on 23rd August 1927.

Even when Jane Addams was in her seventies right-wing figures continued to attack her as the "most dangerous woman" in the United States. In 1934 Elizabeth Dilling wrote in her book, The Red Network, that: "Jane Addams has been able to do more probably than any other living woman to popularize pacifism and to introduce radicalism into colleges, settlements, and respectable circles. The influence of her radical proteges, who consider Hull House their home center, reaches out all over the world."

Jane Addams, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931, remained president of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom until her death on 21st May, 1935.

On this day in 1888 Joseph Patrick Kennedy, the son of Patrick Joseph Kennedy and Mary Augusta Hickey Kennedy, was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on 6th September, 1888. His father was the owner of the wine and spirit importation business, P. J. Kennedy and Company, and a leading figure in the local Democratic Party. All of Kennedy's grandparents had emigrated to Massachusetts in the 1840s to escape the Irish famine.

Kennedy studied at Harvard University and in 1914 married Rose Fitzgerald, the daughter of John Francis Fitzgerald, the mayor of Boston. The couple had nine children: Joseph (25th July, 1915), John (29th May, 1917), Rose (13th September, 1918), Kathleen (20th February, 1920), Eunice (10th July, 1921), Patricia (6th May, 1924), Robert (20th November, 1925), Jean (20th February, 1928) and Edward (22nd September, 1932).

In 1919 Kennedy became manager of Hayden, Stone and Company, where he became an expert in dealing on the Wall Street Stock Market. He became a multi-millionaire and retired from the business just before the Wall Street Crash. Kennedy went on to become a motion-picture tycoon. It is estimated that Kennedy made over $5 million ($67.7 million in today's money) from his investments in Hollywood. While in Hollywood he had a three-year affair with film star Gloria Swanson.

Kennedy was an active member of the Democratic Party and was a strong supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt. During Roosevelt's 1932 presidential election he donated, loaned, and raised a substantial amount of money for the campaign. 1934 President Roosevelt appointed Kennedy chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission. A colleague asked Roosevelt why he had appointed "such a crook". Roosevelt replied: "Takes one to catch one." With his inside knowledge of the system Kennedy was able to outlaw those speculative practices that had made him rich but had contributed to the Wall Street Crash.

Kennedy also helped Roosevelt in his struggle with Father Charles Coughlin, an Irish-Canadian priest in Detroit, who became the most prominent Roman Catholic spokesman on political and financial issues in the 1930s. It was estimated that Coughlin's radio broadcasts were getting an audience of 30 million people. He was also having to employ twenty-six secretaries to deal with the 400,000 letters a week he was receiving from his listeners. In 1936 Coughlin accused Roosevelt of "leaning toward international socialism or sovietism". Kennedy now worked with Bishop Francis Spellman to remove Coughlin from the radio to undermine his influence among Irish Americans.

In 1937 Kennedy was appointed United States Ambassador to Britain. Joseph E. Persico, the author of Roosevelt's Secret War (2001) has argued: "The President may have had an ulterior motive. Joe Kennedy had proved something of a misguided missile in Washington. The right wing saw him as a renegade, a businessman who attacked his own kind. The left painted him as a man who could be troublesome for labor. Within the administration, he was counted a power-hungry publicity hound, a harsh critic of the administration when it suited him, and a man whose business dealings might not stand up to close scrutiny." Henry Morgenthau was upset by the appointment and demanded a meeting with Roosevelt. He later claimed that Roosevelt told him: "Kennedy is too dangerous to have around here... I have made arrangements to have Joe Kennedy watched hourly and the first time he opens his mouth and criticizes me, I will fire him."

In December 1939, after the outbreak of the Second World War, Kennedy informed Roosevelt that Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, was "ruthless and scheming" and was in close touch with an "American clique... notably, certain strong Jewish leaders" who wanted the United States to intervene in the conflict. Two months later Harold Ickes claimed that Kennedy informed William Bullitt that at a meeting with Joseph M. Patterson and Doris Fleeson of the New York Daily News: "Before long he (Kennedy) was saying that Germany would win, that everything in France and England would go to hell, and that his one interest was in saving his money for his children. He began to criticize the President very sharply, whereupon Bill (Bullitt) took issue with him... Bill told him that he was disloyal and that he had no right to say what he had before Patterson and Fleeson."

Kennedy soon came to the conclusion that the island was a lost cause and he considered aid to Britain fruitless. Kennedy, an isolationist, consistently warned Roosevelt "against holding the bag in a war in which the Allies expect to be beaten." Averell Harriman later explained the thinking of Kennedy and other isolationists: "After World War I, there was a surge of isolationism, a feeling there was no reason for getting involved in another war... We made a mistake and there were a lot of debts owed by European countries. The country went isolationist.

On 27th May, 1940, Kennedy told Secretary of State Cordell Hull that "only a miracle could save the Britsh Army from annihilation." The "miracle" came at Dunkirk. However, Kennedy was still not convinced and Neville Chamberlain wrote in his diary in July 1940: "Saw Joe Kennedy who says everyone in the USA thinks we shall be beaten before the end of the month."

When Winston Churchill became prime minister in May 1940 he appointed William Stephenson as the head of the British Security Coordination (BSC) that was based in New York City. Churchill told Stephenson: "You know what you must do at once. We have discussed it most fully, and there is a complete fusion of minds between us. You are to be my personal representative in the United States. I will ensure that you have the full support of all the resources at my command. I know that you will have success, and the good Lord will guide your efforts as He will ours." Charles Howard Ellis said that he selected Stephenson because: "Firstly, he was Canadian. Secondly, he had very good American connections... he had a sort of fox terrier character, and if he undertook something, he would carry it through."

Stephenson knew that with leading officials supporting isolationism he had to overcome these barriers. His main ally in this was another friend, William Donovan, who he had met in the First World War. "The procurement of certain supplies for Britain was high on my priority list and it was the burning urgency of this requirement that made me instinctively concentrate on the single individual who could help me. I turned to Bill Donovan." Donovan arranged meetings with Henry Stimson (Secretary of War), Cordell Hull (Secretary of State) and Frank Knox (Secretary of the Navy). The main topic was Britain's lack of destroyers and the possibility of finding a formula for transfer of fifty "over-age" destroyers to the Royal Navy without a legal breach of U.S. neutrality legislation.

It was decided to send Donovan to Britain on a fact-finding mission. Donovan took with him the journalist Edgar Ansel Mowrer. He left on 14th July, 1940. When he heard the news, Joseph P. Kennedy complained: "Our staff, I think is getting all the information that possibility can be gathered, and to send a new man here at this time is to me the height of nonsense and a definite blow to good organization." He added that the trip would "simply result in causing confusion and misunderstanding on the part of the British". Andrew Lycett has argued: "Nothing was held back from the big American. British planners had decided to take him completely into their confidence and share their most prized military secrets in the hope that he would return home even more convinced of their resourcefulness and determination to win the war." According to Randolph Churchill, during this period Kennedy was seen by the British government as an enemy: "We had reached the point of bugging potential traitors and enemies. Joe Kennedy, the American ambassador, came under electronic surveillance."

William Donovan arrived back in the United States in early August, 1940. In his report to President Franklin D. Roosevelt he argued: "(1) That the British would fight to the last ditch. (2) They could not hope to hold to hold the last ditch unless they got supplies at least from America. (3) That supplies were of no avail unless they were delivered to the fighting front - in short, that protecting the lines of communication was a sine qua non. (4) That Fifth Column activity was an important factor." Donovan also urged that the government should sack Ambassador Joseph Kennedy, who was predicting a German victory. Roosevelt took Donovan's advice and in November, 1940, he was forced to resign. Edgar Ansel Mowrer also wrote a series of articles, based on information supplied by William Stephenson, that Nazi Germany posed a serious threat to the United States.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor Kennedy was keen to help with the war effort but was not invited to do so. It is believed that Kennedy wanted to challenge Roosevelt for the nomination in 1944 but he decided against it and eventually encouraged Irish-American and Roman Catholics to vote for the incumbant. During the war, Kennedy's eldest son, Joseph Kennedy was killed while serving in the armed forces, whereas his second son, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, served with distinction with the Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron.

After the war Kennedy concentrated on helping the political careers of his three surviving sons. John Fitzgerald Kennedy became president but was assassinated in 1963. Robert Kennedy served as U.S. attorney general and as senator from New York before being murdered in 1968. Edward Kennedy, a senator from Massachusetts, was the front-runner to become the Democratic Party presidential candidate until the death of Mary Jo Kopechne in July, 1969.

Joseph Patrick Kennedy died on 18th November, 1969.

On this day in 1914 Arthur Conan Doyle makes speech in favour of joining the Armed Forces.

There was a time for all things in the world. There was a time for games, there was a time for business, and there was a time for domestic life. There was a time for everything, but there is only time for one thing now, and that thing is war. If the cricketer had a straight eye let him look along the barrel of a rifle. If a footballer had strength of limb let them serve and march in the field of battle.

but there's only one field today where you can get honour." (21st October, 1914)

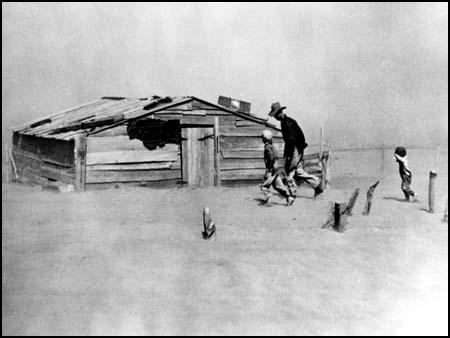

On this day in 1936 Franklin D. Roosevelt makes radio broadcast on the Dust Bowl.

I have been on a journey of husbandry. I went primarily to see at first hand conditions in the drought states; to see how effectively Federal and local authorities are taking care of pressing problems of relief and also how they are to work together to defend the people of this country against the effects of future droughts.

I saw drought devastation in nine states.

I talked with families who had lost their wheat crop, lost their corn crop, lost their livestock, lost the water in their well, lost their garden and come through to the end of the summer without one dollar of cash resources, facing a winter without feed or food -- facing a planting season without seed to put in the ground.

That was the extreme case, but there are thousands and thousands of families on western farms who share the same difficulties.

I saw cattlemen who because of lack of grass or lack of winter feed have been compelled to sell all but their breeding stock and will need help to carry even these through the coming winter. I saw livestock kept alive only because water had been brought to them long distances in tank cars. I saw other farm families who have not lost everything but who, because they have made only partial crops, must have some form of help if they are to continue farming next spring.

I shall never forget the fields of wheat so blasted by heat that they cannot be harvested. I shall never forget field after field of corn stunted, earless and stripped of leaves, for what the sun left the grasshoppers took. I saw brown pastures which would not keep a cow on fifty acres.

Yet I would not have you think for a single minute that there is permanent disaster in these drought regions, or that the picture I saw meant depopulating these areas. No cracked earth, no blistering sun, no burning wind, no grasshoppers, are a permanent match for the indomitable American farmers and stockmen and their wives and children who have carried on through desperate days, and inspire us with their self-reliance, their tenacity and their courage. It was their fathers' task to make homes; it is their task to keep those homes; it is our task to help them with their fight.

On this day in 1963 Senator Wayne Morse warns against getting involved in the Vietnam War.

"The policy of our Government to continue to support military dictatorship is costing us heavily in prestige around the world, because the policy proves us to be hypocritical... So long as Diem is the head of the Government of South Vietnam, we continue to support a tyrant, we continue to support a police-state dictator... On the basis of the present policies that prevail there, South Vietnam is not worth the life of a single American boy."