The Great Depression in Britain

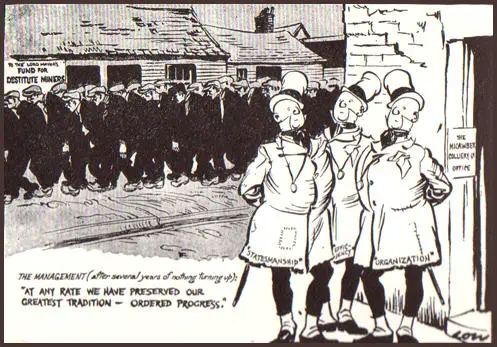

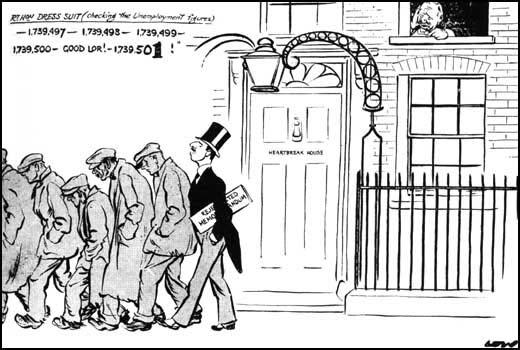

In January 1930 unemployment in Britain reached 1,533,000 (12.4%). By March, the figure was 1,731,000 (13.7%). Oswald Mosley proposed a programme that he believed would help deal with the growing problem of unemployment in Britain. Mosley argued that unemployment could be radically reduced by a £200m public-works programme on the lines advocated by the John Maynard Keynes and the Trade Union Congress. However, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Snowden, who was a strong believer in laissez-faire economics, and disliked the proposals. (1) Ramsay MacDonald was unhappy with Snowden's "hard dogmatism exposed in words and tones as hard as the ideas" but he also dismissed "all the humbug of curing unemployment by Exchequer grants." (2)

Ramsay MacDonald passed the Mosley Memorandum to a committee consisting of Philip Snowden, Tom Shaw, Arthur Greenwood and Margaret Bondfield. The committee reported back on 1st May. Mosley's administrative proposals, the committee claimed "cut at the root of the individual responsibilities of Ministers, the special responsibility of the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the sphere of finance, and the collective responsibility of the Cabinet to Parliament". The Snowden Report went onto argue that state action to reduce unemployment was highly dangerous. To go further than current government policy "would be to plunge the country into ruin". (3)

MacDonald recorded in his diary what happened when Oswald Mosley heard the news about his proposals being rejected. "Mosley came to see me... had to see me urgently: informed me he was to resign. I reasoned with him and got him to hold his decision over till we had further conversations. Went down to Cabinet Room late for meeting. Soon in difficulties. Mosley would get away from practical work into speculative experiments. Very bad impression. Thomas light, inconsistent but pushful and resourceful; others overwhelmed and Mosley on the verge of being offensively vain in himself." (4)

Mosley was not trusted by most of his fellow MPs. He came from an aristocratic background and first entered the House of Commons as a representative of the Conservative Party. One Labour Party MP said Mosley had a habit of speaking to his colleagues "as though he were a feudal landlord abusing tenants who are in arrears with their rent". (5) John Bew described Mosley as "handsome... lithe and black and shiny... he looked like a panther but behaved like a hyena". (6)

At a meeting of Labour MPs took place on 21st May where Oswald Mosley outlined his proposals. This included the provision of old-age pensions at sixty, the raising of the school-leaving age and an expansion in the road programme. He gained support from George Lansbury and Tom Johnson, but Arthur Henderson, speaking on behalf of MacDonald, appealed to Mosley to withdraw his motion so that his proposals could be discussed in detail at later meetings. Mosley insisted on putting his motion to the vote and was beaten by 210 to 29. (7)

Mosley now resigned from the government and was replaced by Clement Attlee. It has been claimed that MacDonald was so fed up with Mosley that he looked around him and choose the "most uninteresting, unimaginative but most reliable among his backbenchers to replace the fallen angel". Winston Churchill said he was "a modest little man, with plenty to be modest about". Mosley was more generous as he accepted that he had "a clear, incisive and honest mind within the limits of his range". However, he added, in agreeing to take his job, Attlee "must be reckoned as content to join a government visibly breaking the pledges on which he was elected." (8)

In June, 1930, unemployment in Britain reached 1,946,000 (15.4%) and by the end of the year it reached a staggering 2,725,000 (19.9%). MacDonald responded to the crisis by asking John Maynard Keynes to become a chairman of the Economic Advisory Council to "advise His Majesty's Government in economic matters". Members of the committee included J. A. Hobson, George Douglas Cole, Walter Citrine, Hubert Henderson, Hugh Macmillan, Walter Layton, William Weir and Andrew Rae Duncan. However, Keynes was disappointed by MacDonald's reaction to his advice: "Politicians rarely look to economists to tell them what to do: mainly to give them arguments for doing things they want to do, or for not doing things they don't want to do." (9)

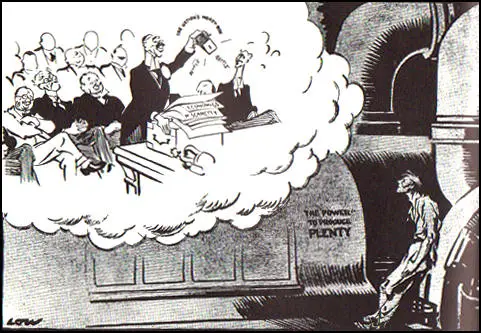

Cole later recalled: "Philip Snowden held a strong position in the Party as its one recognised financial expert... MacDonald nor most of the other members of the Cabinet had any understanding of finance, or even thought they had... The Economic Advisory Council, of which I was a member, discussed the situation again and again; and some of us, including Keynes, tried to get MacDonald to understand the sheer necessity of adopting some definite policy for stopping the rot. Snowden was inflexible; and MacDonald could not make up his mind, with the consequence that Great Britain drifted steadily towards a disaster." (10)

The Gold Standard

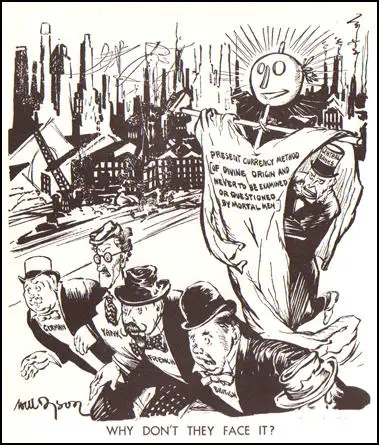

During the 19th century all the main countries of the world adhered to a fixed-exchange rate system known as the Gold Standard. "Their domestic currencies were freely convertible into specified amounts of gold; they maintained fixed proportions between the quantity of money in circulation and the gold reserves of their central banks. An ounce of gold was worth 3.83 pounds sterling and dollars 18.60, giving a sterling-dollar exchange rate of 4.86. The appeal of the gold standard was that it provided not just exchange rate stability, which encouraged international trade, but promised long-run stability in prices, since the obligation to maintain convertibility acted as a check on the 'over-issue' of notes by governments." (11)

By the 20th century the gold standard was seen as providing stability, low interest rates and a steady expansion in world trade. On the outbreak of the First World War Germany immediately left the gold standard. Britain followed soon afterwards. In financing the war and abandoning gold, many of the belligerents suffered serious problems with inflation. Price levels doubled in Britain, tripled in France and quadrupled in Italy. The economist, Richard G. Lipsey, has pointed out that the gold standard could not cope with the consequences of a world war. (12)

Under the terms of the Versailles Treaty the Allies confiscated Germany's gold supplies. They were therefore unable to return to the gold standard. During the Occupation of the Ruhr the German central bank (Reichsbank) issued enormous sums of non-convertible marks to support workers who were on strike against the French occupation and to buy foreign currency for reparations; this led to the German hyper-inflation of the early 1920s and helped to undermine confidence in the country's financial system. It also provided a warning of what could happen when a country managed its own currency. (13)

Winston Churchill rejoined the Conservative Party and on 6th November, 1924 Stanley Baldwin appointed him as Chancellor of the Exchequer. His biographer, Clive Ponting pointed out that he "had no experience of financial or economic matters". He had "taken virtually no interest in such questions and the only ideas on economic policy he was known to advocate were free trade and sound finance". Ponting adds that "he was, unusually for him, lacking in self-confidence on economic policy and proved much more willing to accept conventional wisdom and the advice of experts." (14)

Otto Niemeyer, Controller of Finance at the Treasury, and Montagu Norman, Governor of the Bank of England, and a handful of bankers argued that Churchill should return to the gold standard. Churchill had discussions with John Maynard Keynes and Reginald McKenna, chairman of the Midland Bank, who were both against the move. The Federation of British Industry, favoured postponement. Industrialists were not consulted, Norman commented that their views on the subject was comparable to asking shipyard workers what they thought about the "design of a battleship." (15)

According to Percy J. Grigg, Churchill's private secretary, at a meeting on 17th March, 1925, Keynes told the Chancellor of the Exchequer, that a return to the gold standard would result in an increase in "unemployment and downward adjustment of wages and prolonged strikes in some of the heavy industries, at the end of which it would be found that these industries had undergone a permanent contraction". It was therefore "better to keep domestic prices and nominal wage rates stable and allow the exchanges to fluctuate for the time being." (16)

Churchill found Keynes arguments convincing. He told Niemeyer he was concerned about the attitude of the Governor of the Bank of England: "The Treasury have never, it seems to me, faced the profound significance of what Mr Keynes calls the 'paradox of unemployment amidst dearth'. The Governor shows himself perfectly happy at the spectacle of Britain possessing the finest credit in the world simultaneously with a million and a quarter unemployed. It is impossible not to regard the object of full employment as at least equal, and probably superior, to the other valuables objectives you mention... The community lacks goods, and a million and a quarter people lack work. It is certainly one of the highest functions of national finance to bridge the gulf between the two." (17)

Despite these concerns, on 28th April, 1925, Churchill announced the return to the gold standard in the House of Commons. Churchill fixed the price at the pre-war rate of $4.86. "If we had not taken this action the whole of the rest of the British Empire would have taken it without us, and it would have come to a gold standard, not on the basis of the pound sterling, but a gold standard of the dollar." (18)

Keynes offered Geoffrey Dawson, the editor of The Times, a series of articles on the effects of the return to the gold standard. When he saw them he turned them down: "They are extraordinary clever and very amusing; but I really feel that, published in The Times at this particular moment, they would do harm and not good." (19) William Maxwell Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, was more receptive and the articles appeared in the Evening Standard, in July, 1925. This was followed by a pamphlet, The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill. (20)

Keynes argued: "Our troubles arose from the fact that sterling's value had gone up by 10 per cent in the previous year. The policy of improving the exchange by 10 per cent involves a reduction of 10 per cent in the sterling receipts of our export industries". But they could not reduce their prices by 10 per cent and remain profitable unless all internal prices and wages fell by 10 per cent. "Thus Mr. Churchill's policy of improving the exchange by 10 per cent was, sooner or later, a policy of reducing everyone's wages by 2s. in the pound." Keynes went on to suggest that workers would be "justified in defending themselves" because they had no guarantee that they would be compensated later by a lower cost of living. (21)

Selina Todd pointed out in The People: The Rise and Fall of the Working Class (2014): "Churchill wanted to raise the value of the pound against other national currencies; a morale boost for those who recalled Britain's imperial pre-eminence in the years before 1914 but - as the economist John Maynard Keynes predicted - disastrous for the British economy. In 1914 Britain's government and industrialists had been able to rely on the empire both to produce and consume British goods. But by 1925 British industrialists relied heavily on exporting goods, and manufactures had to price their goods competitively in the free international market. Churchill's move made exports prohibitively expensive." (22)

It has been argued that Churchill overvalued sterling by at least ten per cent. "Domestically the results were disastrous. The overvalued pound meant the costs had to be reduced in an unavailing attempt to keep exports competitive and this at a time when real wages were already below 1914 levels. Attempts to impose further wage reductions inevitably led to industrial disputes, lock-outs, strikes, rising unemployment and increased social strains. The overvalued pound made perhaps as many as 700,000 people unemployed. The impact showed up the 1925 decision for what it was - a banking and financial policy designed to benefit the City of London." (23)

A Treatise on Money

John Maynard Keynes published A Treatise on Money on 24th October 1930. It was the product of a long intellectual struggle to escape from the ideas in which he had been reared, later dubbed "classical economics"; for example, the Ricardian view that supply creates its own demand. "The focus of the book was on money and prices rather than on output and employment: it contained a full study of the operation of the monetary system, national and international. Fluctuations in prices were no longer explained in terms of changes in the stock of money as in the quantity theory, but in terms of the pressure of demand on the available supply of resources; and the pressure of demand was represented as varying with the magnitude of any divergence between the volume of investment and the availability of savings to finance it." (24)

The traditional view was that unemployment would force down wages and eventually people would be able to sell their services for less and would be "priced into a job". Keynes rejected the view that this "equilibrating mechanism" always worked in this way and sometimes wages are not always "responsive to unemployment". In fact, since the slowdown in the economy began in 1924 wages had not declined. In one lecture he pointed out that wage rates were fixed by "social and historical forces", not by the "marginal productivity of labour". (25)

Keynes made this point in more detail in more detail in a BBC radio interview: "The existence of the dole undoubtedly diminishes the pressure on the individual man to accept a rate of wages or a kind of employment which is not just what he wants or what he is used to. In the old days the pressure on the unemployed was to get back somehow or other into employment, and if that was so to-day surely it would have more effect on the prevailing rate of wages... I cannot help feeling that we must partly attribute to the dole the extraordinary fact.... that, in, spite of the fall in prices, and the fall in the cost of living, and the heavy unemployment, wages have practically not fallen at all since 1924." (26)

Nicholas Kaldor has suggested that Keynes criticised the employers for reducing wages and the Bank of England for "imposing high interest rates in an attempt to limit overseas lending to the amount that the level of net exports". By examining "exports, the trade balance, the flow of overseas lending, the nature of the adjustment mechanism in foreign trade, the instruments employed by the Bank of England" he was able to show the system was generating "a low employment trap". (27)

John Maynard Keynes went on to argue that wages had not fallen recently. Jacques Rueff, a conservative French economist, and supporter of the free-market, argued that the problem was that British workers were receiving too much unemployment pay: "In actual fact the wages level is a result of collective contracts, but these contracts would never have been observed by the workmen if they had not been sure of receiving an indemnity which differed little from their wages. It is the dole, therefore, that has made trade union discipline possible... Therefore we may assume that the dole is the underlying cause of the unemployment which has been so cruelly inflicted on England since 1920." (28)

Hugh Macmillan, a Conservative Party member of the Economic Advisory Council agreed and argued that social security benefits had prevented "economic laws" from working. Keynes replied: "I do not think they are sins against economic law. I do not think it is any more economic law that wages should go down easily than that they should not. It is a question of facts. Economic law does not lay down the facts, it tells you what the consequences are." He insisted unemployment benefits were not the cause of unemployment. "I think we are forced by the use of the wrong weapon to have a hospital because it has resulted in there being so many wounded." (29)

Ramsay MacDonald and Philip Snowden had several meetings with the Economic Advisory Council. Keynes described these sessions as visits to the "monkey house". Keynes, who joined forces with George Douglas Cole and Walter Citrine, in favour of "a programme of productive and useful home development". It was claimed that the businessmen wanted to reduce costs, including taxes. Keynes also argued for controls on the export of capital. Hugh Dalton explained that MacDonald and Snowden would not agree to an enquiry into monetary policy or the state in relation to unemployment policy. Keynes responded bitterly at one meeting where he described himself as "the only socialist present". (30)

Hubert Henderson, who had co-written Can Lloyd George Do It?, also now became one of Keynes opponents. He told Keynes with the slump gathering force, the budgetary cost of public works schemes was bound to shoot up, as the projects financed became progressively less remunerative. Henderson feared that "with an increasing hole in the Budget, and increasing apprehension, until you were faced with either abandoning the whole policy or facing a real panic - flight from the pound and all the rest". (31)

Keynes wrote several articles for The Nation on the economic crisis. On 13th December he praised the manifesto published by Oswald Mosley and signed by seventeen Labour Party MPs as "offering a starting point for thought and action". The following week he asked: "Is the man in the street now awakening from a pleasant dream to face the darkness of facts? Or dropping off into a nightmare that will pass away?" He then answered his own question: "This is not a dream. This is a nightmare. For the resources of nature and men's devices are just as fertile and productive as they ever were." (32)

Keynes realised that the political balance of the left-centre had shifted decisively to the Labour Party. He therefore opened talks with Arnold Bennett, the chairman of the New Statesman board. Keynes told David Lloyd George that "it would be difficult or impossible to make a real success of both papers separately since we appeal to almost identical politics. But the combined paper should be capable of establishing itself securely and being an important organ of opinion." (33)

The first issue of the New Statesman and Nation appeared on 28th February 1931. It styled itself as an independent organ of the left, without special affiliation to a political party. The editor was Kingsley Martin who later commented: "Maynard Keynes was to play a crucial part in my life. He had a reputation for arrogance when he was young, and I doubt if he ever learnt to suffer fools gladly. He had the most powerful and formidable mind I ever worked with; he had imagination and was constructive as well as iconoclastic. He was often unscrupulous in argument, and for years was the only person I feared, because he could so easily make me feel a fool. He was one of the few economists I've ever known who realised that statistics represented human beings." (34)

The George May Committee

Unemployment continued to rise and the national fund was now in deficit. Austen Morgan, has argued that when Ramsay MacDonald refused to become master of events, they began to take control of the Labour government: "With the unemployed the principal sufferers of the world recession, he allowed middle-class opinion to target unemployment benefit as a problem... With Snowden at the Treasury, it was only a matter of time before the economic issue was being defined as an unbalanced budget." (35)

Philip Snowden rejected Keynes ideas and this resulted in the resignation of Charles Trevelyan, the Minister of Education. "For some time I have realised that I am very much out of sympathy with the general method of Government policy. In the present disastrous condition of trade it seems to me that the crisis requires big Socialist measures. We ought to be demonstrating to the country the alternatives to economy and protection. Our value as a Government today should be to make people realise that Socialism is that alternative." (36)

Trevelyan told a meeting of the Parliamentary Labour Party that the main reason he had resigned: "I have for some time been painfully aware that I am utterly dissatisfied with the main strategy of the leaders of the party. But I thought it my duty to hold on as long as I had a definite job in trying to pass the Education Bill. I never expected a complete breakthrough to Socialism in this Parliament. But I did expect it to prepare the way by a Government which in spirit and vigour made such a contrast with the Tories and Liberals that we should be sure of conclusive victory next time."

He attacked the government for refusing to introduce socialist measures to deal with the economic crisis: "Now we are plunged into an exampled trade depression and suffering the appalling record of unemployment. It is a crisis almost as terrible as war. The people are in just the mood to accept a new and bold attempt to deal with radical evils. But all we have got is a declaration of economy from the Chancellor of the Exchequer. We apparently have opted, almost without discussion, the policy of economy. It implies a faith, a faith that reduction of expenditure is the way to salvation. No comrades. It is not good enough for a Socialist party to meet this crisis with economy. The very root of our faith is the prosperity comes from the high spending power of the people, and that public expenditure on the social services is always remunerative." (37)

In February 1931, on the advice of Philip Snowden, MacDonald asked George May, the Secretary of the Prudential Assurance Company, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problems. Other members of the committee included Arthur Pugh (trade unionist), Charles Latham (trade unionist), Patrick Ashley Cooper (Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company), Mark Webster Jenkinson (Vickers Armstrong Shipbuilders), William Plender (President of the Institute of Chartered Accountants) and Thomas Royden (Thomas Royden & Sons Shipping Company). (38)

A. J. P. Taylor has pointed out that four of the May Committee were leading capitalists, whereas only two represented the labour movement: "Snowden calculated that a fearsome report from this committee would terrify Labour into accepting economy, and the Conservatives into accepting increased taxation. Meanwhile he produced a stop-gap budget in April, intending to produce a second, more severe budget in the autumn." Snowden made speeches in favour of "national unity" hoping that he would get help from the other political parties to push through harsh measures. (39)

Snowden came increasing under attack from England's leading economists. John Maynard Keynes criticised Snowden's belief in free-trade and urged the introduction of an import tax in order that Britain might resume the vacant financial leadership of the world, which no one else had the experience or the public spirit to occupy. Keynes believed this measure would create a budget surplus. (40) Others questioned the wisdom of devoting £60m to paying off the national debt. (41) According to Edward Vallance for Ramsay MacDonald it was "vitally important that the still-young Labour Party present the face of a responsible party of government... like so many Labour prime ministers after him, the quest for respectability led him further away from the party's roots." (42)

On 14th July, the Economic Advisory Council published its report on the state of the economy. Chaired by Hugh Macmillan, committee members included John Maynard Keynes, J. A. Hobson, George Douglas Cole, Walter Citrine, Hubert Henderson, Walter Layton, William Weir and Andrew Rae Duncan. The report drew attention to Britain's balance of payments. "The export of manufactured goods had not paid for the import of food and raw materials for over a hundred years but this had been made up by so-called 'invisible' earnings, such as banking, shipping and the interest on foreign income. These had declined with the recession. Crude estimates a new economic indicator - suggested that Britain was about enter into a balance of payments deficit... By way of solution, they proposed a revenue tariff." (43)

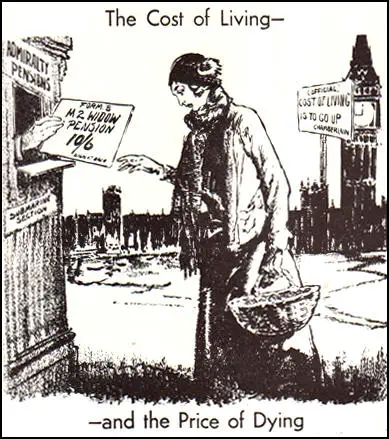

In July, 1931, the George May Committee produced (the two trade unionists refused to sign the document) its report that presented a picture of Great Britain on the verge of financial disaster. It proposed cutting £96,000,000 off the national expenditure. Of this total £66,500,000 was to be saved by cutting unemployment benefits by 20 per cent and imposing a means test on applicants for transitional benefit. Another £13,000,000 was to be saved by cutting teachers' salaries and grants in aid of them, another £3,500,000 by cutting service and police pay, another £8,000,000 by reducing public works expenditure for the maintenance of employment. "Apart from the direct effects of these proposed cuts, they would of course have given the signal for a general campaign to reduce wages; and this was doubtless a part of the Committee's intention." (44)

The five rich men on the committee recommended, not surprisingly, that only £24 million of this deficit should be met by increased taxation. As David W. Howell has pointed out: "A committee majority of actuaries, accountants, and bankers produced a report urging drastic economies; Latham and Pugh wrote a minority report that largely reflected the thinking of the TUC and its research department. Although they accepted the majority's contentious estimate of the budget deficit as £120 million and endorsed some economies, they considered the underlying economic difficulties not to be the result of excessive public expenditure, but of post-war deflation, the return to the gold standard, and the fall in world prices. An equitable solution should include taxation of holders of fixed-interest securities who had benefited from the fall in prices." (45)

William Ashworth, the author of An Economic History of England 1870-1939 (1960) has argued: "The report presented an overdrawn picture of the existing financial position; its diagnosis of the causes underlying it was inaccurate; and many of its proposals (including the biggest of them) were not only harsh but were likely to make the economic situation worse, not better." (46) Keynes reacted with great anger as it was the complete opposite of what he had been telling the government to do and called the May Report "the most foolish document I ever had the misfortune to read". (47)

The May Report had been intended to be used as a weapon to use against those Labour MPs calling for increased public expenditure. What it did in fact was to create abroad a belief in the insolvency of Britain and in the insecurity of the British currency, and thus to start a run on sterling, vast amounts of which were held by foreigners who had exchanged their own currencies for it in the belief that it was "as good as gold". This foreign-owned sterling was now exchanged into gold or dollars and soon began to threaten the stability of the pound. (48)

The Labour government officially rejected the report because MacDonald and Snowden could not persuade their Cabinet colleagues to accept May's recommendations. MacDonald and Snowden now formed a small committee, made up of themselves and Arthur Henderson, Jimmy Thomas and William Graham, three people they thought they could persuade to accept public spending cuts. Their report was published on 31st July, the last day of parliament sitting. It was a bland document that made no statement on May's recommendations. (49)

On 5th August, John Maynard Keynes wrote to MacDonald, arguing that the committee's recommendations clearly represented "an effort to make the existing deflation effective by bringing incomes down to the level of prices" and if adopted in isolation, they would result in "a most gross perversion of social justice". Keynes suggested that the best way to deal with the crisis was to leave the gold standard and devalue sterling. (50)

Philip Snowden presented his recommendations to the Cabinet on 20th August. It included the plan to raise approximately £90 million from increased taxation and to cut expenditure by £99 million. £67 million was to come from unemployment insurance, £12 million from education and the rest from the armed services, roads and a variety of smaller programmes. Most members of the Cabinet rejected the idea of the proposed cut in unemployment benefit and the meeting ended without any decisions being made. Clement Attlee, who was a supporter of Keynes, condemned Snowden for his "misplaced fidelity to laissez-faire economics". (51)

Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Susan Lawrence both decided to resign from the government if the cuts to the unemployment benefit went ahead: Pethick-Lawrence wrote: "Susan Lawrence came to see me. As Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health, she was concerned with the proposed cuts in unemployment relief, which she regarded as dreadful. We discussed the whole situation and agreed that, if the Cabinet decided to accept the cuts in their entirety, we would both resign from the Government." (52)

Arthur Henderson argued that rather do what the bankers wanted, Labour should had over responsibility to the Conservatives and Liberals and leave office as a united party. The following day MacDonald and Snowden had a private meeting with Neville Chamberlain, Samuel Hoare, Herbert Samuel and Donald MacLean to discuss the plans to cut government expenditure. Chamberlain argued against the increase in taxation and called for further cuts in unemployment benefit. MacDonald also had meetings with trade union leaders, including Walter Citrine and Ernest Bevin. They made it clear they would resist any attempts to put "new burdens on the unemployed". Sidney Webb later told his wife Beatrice Webb that the trade union leaders were "pigs" as they "won't agree to any cuts of unemployment insurance benefits or salaries or wages". (53)

At another meeting on 23rd August, 1931, nine members (Arthur Henderson, George Lansbury, John R. Clynes, William Graham, Albert Alexander, Arthur Greenwood, Tom Johnson, William Adamson and Christopher Addison) of the Cabinet stated that they would resign rather than accept the unemployment cuts. A. J. P. Taylor has argued: "The other eleven were presumably ready to go along with MacDonald. Six of these had a middle-class or upper-class background; of the minority only one (Addison)... Clearly the government could not go on. Nine members were too many to lose." (54)

That night Ramsay MacDonald went to see George V about the economic crisis. He warned the King that several Cabinet ministers were likely to resign if he tried to cut unemployment benefit. MacDonald wrote in his diary: "King most friendly and expressed thanks and confidence. I then reported situation and at end I told him that after tonight I might be of no further use, and should resign with the whole Cabinet.... He said that he believed I was the only person who could carry the country through." (55)

MacDonald told his son, Malcolm MacDonald, about what happened at the meeting: "The King has implored J.R.M. to form a National Government. Baldwin and Samuel are both willing to serve under him. This Government would last about five weeks, to tide over the crisis. It would be the end, in his own opinion, of J.R.M.'s political career. (Though personally I think he would come back after two or three years, though never again to the Premiership. This is an awful decision for the P.M. to make. To break so with the Labour Party would be painful in the extreme. Yet J.R.M. knows what the country needs and wants in this crisis, and it is a question whether it is not his duty to form a Government representative of all three parties to tide over a few weeks, till the danger of financial crash is past - and damn the consequences to himself after that." (56)

After another Cabinet meeting where no agreement about how to deal with the economic crisis could be achieved, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to resign. Sir Clive Wigram, the King's private secretary, later recalled that George V "impressed upon the Prime Minister that he was the only man to lead the country through the crisis and hoped that he would reconsider the situation." At a meeting with Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain and Herbert Samuel, MacDonald told them that if he joined a National Government it "meant his death warrant". According to Chamberlain he said "he would be a ridiculous figure unable to command support and would bring odium on us as well as himself." (57)

The National Government

On 24th August 1931 King George V had a meeting with the leaders of the Conservative and Liberal parties. Herbert Samuel later recorded that he told the king that MacDonald should be maintained in office "in view of the fact that the necessary economies would prove most unpalatable to the working class". He added that MacDonald was "the ruling class's ideal candidate for imposing a balanced budget at the expense of the working class." (58)

Later that day MacDonald returned to the palace and had another meeting with the King. MacDonald told the King that he had the Cabinet's resignation in his pocket. The King replied that he hoped that MacDonald "would help in the formation of a National Government." He added that by "remaining at his post, his position and reputation would be much more enhanced than if he surrendered the Government of the country at such a crisis." Eventually, he agreed to continue to serve as Prime Minister. George V congratulated all three men "for ensuring that the country would not be left governless." (59)

Ramsay MacDonald was only able to persuade three other members of the Labour Party to serve in the National Government: Philip Snowden (Chancellor of the Exchequer) Jimmy Thomas (Colonial Secretary) and John Sankey (Lord Chancellor). The Conservatives had four places and the Liberals two: Stanley Baldwin (Lord President), Samuel Hoare (Secretary for India), Neville Chamberlain (Minister of Health), Herbert Samuel (Home Secretary), Lord Reading (Foreign Secretary) and Philip Cunliffe-Lister (President of the Board of Trade).

MacDonald's former cabinet colleagues were furious about what he had done. Clement Attlee asked why the workers and the unemployed were to bear the brunt again and not those who sat on profits and grew rich on investments? He complained that MacDonald was a man who had "shed every tag of political convictions he ever had". His so-called National Government was a "shop-soiled pack of cards shuffled and reshuffled". This was "the greatest betrayal in the political history of this country". (60)

G. D. H. Cole had his own explanation of what had happened: "In the case of both Snowden and MacDonald, vanity played an outstanding part. Their vanities, however, were widely different. Snowden was utterly sure of being always and entirely both right and righteous, and had no scruples over his methods of handling colleagues whom he regarded as fools. MacDonald was equally self-righteous, but had no similar confidence that he knew the right answer to every question... He was always seeing the force in the policies put up by his opponents - provided only that they were not to the left of him." (61)

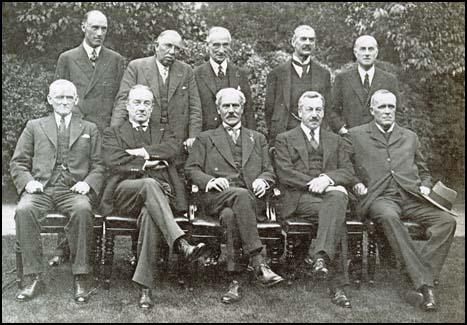

Lord Reading, Neville Chamberlain, Samuel Hoare. Seated, left to right: Philip Snowden,

Stanley Baldwin, Ramsay MacDonald, Herbert Samuel and John Sankey.

Some members of the Labour Party were pleased by the formation of the National Government. Morgan Philips Price commented: "I found Members delighted that Ramsay Macdonald, Philip Snowden and J. H. Thomas had severed themselves from us by their action. We had got rid of the Right Wing without any effort on our part. No one trusted Mr Thomas and Philip Snowden was recognized to be a nineteenth-century Liberal with no longer any place amongst us. State action to remedy the economic crisis was anathema to him. As for Ramsay Macdonald, he was obviously losing his grip on affairs. He had no background of knowledge of economic and financial questions and was hopelessly at sea in a crisis like this. But many, if not most, of the Labour M.P.s thought that at an election we should win hands down." (62)

The Labour Party was appalled by what they considered to be MacDonald's act of treachery. Arthur Henderson commented that MacDonald had never looked into the faces of those who had made it possible for him to be Prime Minister. His close friend, Mary Hamilton, wrote on 28th August: "But greatly as I admire your courage, and ready as I am to believe your gesture may have saved us all, I could not, as I thought the whole situation out on my long journey home, find it possible to support this Government or believe in its policy. It is a very hard decision to make; and this afternoon's party meeting does not make it agreeable to act on - but, there it is. I felt I must write this line to express the deep regret I feel about this, temporary severance between you and the party." (63)

Ramsay MacDonald replied: "Whether you believe it or not, I have saved you, whatever the cost may be to me, but you are all quietly going on drafting manifestoes, talking about opposing cuts in unemployment pay and so on, because I faced the facts a week ago and damned the consequences... If I had agreed to stay in, defied the bankers and a perfect torrent of credit that had been leaving the country day by day, you would all have been overwhelmed and the day you met Parliament you would have been swept out of existence... Still I have always said that the rank and file have not always the same duty as the leaders, and I am willing to apply that now. I dare say you know, however, that for some time I have been very disturbed by the drift in the mind of the Party. I am afraid I am not a machine-made politician, and never will be, and it is far better for me to drop out before it will be impossible for me to make a decent living whilst out of public life." (64)

On 8th September 1931, the National Government's programme of £70 million economy programme was debated in the House of Commons. This included a £13 million cut in unemployment benefit. All those paid by the state, from cabinet ministers and judges down to the armed services and the unemployed, were cut 10 per cent. Teachers, however, were treated as a special case, lost 15 per cent. Tom Johnson, who wound up the debate for the Labour Party, declared that these policies were "not of a National Government but of a Wall Street Government". In the end the Government won by 309 votes to 249. (65)

John Maynard Keynes spoke out against the morality of cutting benefits and public sector pay. He claimed that the plans to reduce the spending on "housing, roads, telephone expansion" was "simply insane". Keynes went on to say the government had been ignoring his advice: "During the last 12 years I have had very little influence, if any, on policy. But in the role of Cassandra, I have had considerable success as a prophet. I declare to you, and I will stake on it any reputation I have, that we have been making in the last few weeks as dreadful errors of policy as deluded statesmen have ever been guilty of." (66)

The cuts in public expenditure did not satisfy the markets. The withdrawals of gold and foreign exchange continued. John Maynard Keynes published an article in the Evening Standard on 10th September, urging import controls and the leaving of the Gold Standard. (67) Two days later he argued in the New Statesman that the government policy "can only delay, it cannot prevent, a recurrence of another crisis similar to that through which we have just passed." (68)

A mutiny of naval ratings at Invergordon on 16th September, led to another run on the pound. That day the Bank of England lost £5 million in defending the currency. This was followed by losing over 10 million on 17th and over 16 million on the 18th. The governor of the Bank of England told the government that it had lost most of its original gold and foreign exchange. On the 20th September, the Cabinet agreed to leave the Gold Standard, something that Keynes had been telling the government to do for several years. (69)

The pound sterling was allowed to float in the international markets and was to fall by more than a quarter. Therefore, devaluation, which the Labour government had destroyed itself in its resistance to this policy, came four weeks after the formation on the National government. The advice of the Bank of England, which had been taken as absolute gospel, was proved to be worthless. Sidney Webb, the former Secretary of State for the Colonies in MacDonald's government, commented: "Nobody told us we could do this." (70)

Ramsay MacDonald still feared for the future, he wrote to a friend that "although we cannot say it in public, the unsettlement regarding sterling and the uncertainty regarding the position of the Government may, at any moment, bring a new crisis, the results of which may well be starvation for great sections of our people, ruin to everybody except a lot of dastardly profiteers and speculators, and the end of our influence in the world." (71)

On 26th September, the Labour Party National Executive decided to expel all members of the National Government including Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey. As David Marquand has pointed out: "In the circumstances, its decision was understandable, perhaps inevitable. The Labour movement had been built on the trade-union ethic of loyalty to majority decisions. MacDonald had defied that ethic; to many Labour activists, he was now a kind of political blackleg, who deserved to be treated accordingly." (72)

1931 General Election

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with several leading Labour figures, including Arthur Henderson, John R. Clynes, Arthur Greenwood, Charles Trevelyan, Herbert Morrison, Emanuel Shinwell, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Hastings Lees-Smith, Hugh Dalton, Susan Lawrence, William Wedgwood Benn, Tom Shaw and Margaret Bondfield losing their seats.

The Government parties polled 14,500,000 votes to Labour's 6,600,000. In the new House of Commons, the Labour Party had only 52 members and the Lloyd George Liberals only 4 . George Lansbury, William Adamson, Clement Attlee and Stafford Cripps were the only leading Labour figures to win their seats. The Labour Party polled 30.5% of the vote reflecting the loss of two million votes, a huge withdrawal of support. The only significant concentration of Labour victories occurred in South Wales where eleven seats were retained, many by large majorities. (73)

MacDonald, now had 556 pro-National Government MPs and had no difficulty pursuing the policies suggested by Sir George May. The new Chancellor of the Exchequer was Neville Chamberlain. MacDonald kept Snowden, Thomas and Sankey in his government but the Conservatives dominated the cabinet with eleven members. In September 1932, Snowden, Samuel and Sinclair resigned over the issue of tariffs on imports. MacDonald wrote in his diary: "I have had doubts as to whether I should stay, but only owing to my own personal feelings. It is a lonely job, but of what I ought to do I never doubted." (74)

Chamberlain gained extra revenues from tariffs but still had difficulty balancing the budget. This problem became worse when he reduced the contribution of direct taxation. To balance this he cut police pay by ten per cent and military expenditure was at its lowest since the war. Chamberlain refused to increase public spending and unemployment continued to rise and reached 23% in August, 1932. MacDonald wrote in his diary that he did not know what to do: "It is not the usual depression. It is really the breakdown of a system." (75)

| Unemployment in the United Kingdom: 1920-1939 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Year | January | March | June | August | October | Average |

1920 | 6.1 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 3.9 |

1921 | 11.2 | 15.4 | 22.4 | 15.6 | 14.5 | 16.9 |

1922 | 17.7 | 16.0 | 13.7 | 12.8 | 12.6 | 14.3 |

| 1923 | 13.3 | 11.7 | 11.3 | 11.8 | 11.7 | 11.7 |

| 1924 | 11.9 | 9.8 | 9.3 | 10.5 | 10.9 | 10.3 |

| 1925 | 11.2 | 11.1 | 11.9 | 12.1 | 11.4 | 11.3 |

| 1926 | 11.0 | 9.8 | 14.6 | 14.0 | 13.6 | 12.5 |

| 1927 | 12.0 | 9.8 | 8.8 | 9.3 | 9.5 | 9.7 |

| 1928 | 10.7 | 9.5 | 10.7 | 11.5 | 11.7 | 10.8 |

| 1929 | 12.2 | 10.0 | 9.6 | 9.9 | 10.3 | 10.4 |

| 1930 | 12.4 | 13.7 | 15.4 | 17.0 | 18.5 | 16.0 |

| 1931 | 21.1 | 21.0 | 21.2 | 21.9 | 21.7 | 21.3 |

| 1932 | 22.2 | 20.8 | 22.2 | 23.0 | 21.9 | 22.1 |

| 1933 | 23.0 | 21.9 | 19.4 | 19.1 | 18.1 | 19.9 |

| 1934 | 18.6 | 17.2 | 16.4 | 16.5 | 16.3 | 16.7 |

| 1935 | 17.6 | 16.4 | 15.4 | 14.9 | 14.5 | 15.5 |

| 1936 | 16.2 | 14.2 | 12.8 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 13.1 |

| 1937 | 12.4 | 11.6 | 10.0 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 10.8 |

| 1938 | 13.2 | 12.7 | 13.2 | 12.6 | 12.7 | 12.9 |

| 1939 | 12.8 | 10.9 | 8.4 | 7.6 | 8.3 | 9.3 |

MacDonald was now a prisoner of the Conservative Party. He opposed the administration of the Means Test to the unemployed but was powerless to object. This represented almost a return to the poor law and when it was enacted it gave rise to considerable working-class opposition. He wrote in his diary that "no vision of general situation and only concern to keep government out of practically everything... deserted by Labour and Liberal parties, the National Government inevitably tends to fundamental Toryism." (76)

MacDonald was now 67 years old and he now began to feel his age. He wrote in his diary: "Trying to get something clear into my head for the House of Commons tomorrow. Cannot be done. Like man flying in mist: can fly all right but cannot see the course. Tomorrow there will be a vague speech impossible to follow." The following day he recorded: "Thoroughly bad speech. Could not get my way at all. The Creator might have devised more humane means for punishing me for over-drive and reckless use of body." (77)

Stanley Baldwin forced MacDonald to give Tory donors honours. He was especially upset by the case of Julian Cahn, who had made his fortune from hire purchase schemes. He wrote in his diary that "Cahn was one of those honours hunters whom I detested." Cahn had used his money to cover up a scandal that involved the Conservative Party: "Baldwin involves me in a scandal of honour by forcing me to give an honour because a man has paid £30,000 to get Tory headquarters and some Tories living and dead out of a mess." (78)

Sweden and the Great Depression

After the Wall Street Crash the whole of Western Europe was impacted by the Great Depression. This was true of Sweden and by 1931, industrial production had declined by 10.3%. The economist, Ernst Wigforss, who was a convert to the ideas of John Maynard Keynes, argued: "We socialists cannot accept a system... where up to 10% of the workers must be unemployed, and during worse times, even more. We refuse to admit that this is necessary and natural despite how much people come armed with theories stating that this must be so." (79)

However, in the 1932 General Election, the Social Democratic Party won 41.7% of the seats. The minor left-wing parties, including the Independent Socialist Party (5.3%) Communist Party (3.0%) agreed to form a minority government with the SDP leader, Per Albin Hansson, as prime minister. Although they did not join the government the Farmers' League agreed to keep them in power in return for support for their agriculture policy. (80)

Hansson appointed Ernst Wigforss, as his finance minister. After leaving the Gold Standard he devalued the Krona, reducing the price of Swedish exports. Wigforss proposed a public work program designed to put unemployed back to work even if this meant budget deficits. This was a radical departure from the policies of previous governments. A balanced budget had always been the main objective. Usually, government loans were only used for investments that were expected to generate future profits such as postal services, railroads or electric power supply. (81)

The first unbalanced budget proposed by Wigforss for the years 1933 and 1934 was criticized for causing inflation and "depriving businesses of capital necessary for their development". To counter these arguments, the Social Democrats moved away from financing public work programs through deficits and proposed an inheritance tax used to finance their plans. The policies of deficit spending and government intervention in the economy, began the creation of the Swedish Welfare State. Wigforss argued for creating "provisional utopias... tentative sketches of a desirable future... They served as a critique of existing social conditions and as a guide to present action, yet could be revised with future experience." (82)

In June 1936, the uneasy majority enforced Hansson's resignation, leaving League chairman Axel Pehrsson-Bramstorp to form a three-month "Holiday Cabinet" until the elections in September. (83) The 1936 General Election saw a surge in support of the Social Democrats with 45.9% of the vote. Along with the Independent Socialists (4.4) and Communist Party (3.3), Hansson formed the next government. This was a popular government and in 1940 General Election the Social Democrats won an overall majority with 53.8% of the vote. Per Albin Hansson declared: "We Social Democrats do not accept a social order with political, cultural and economic privileges or one where the private-owned means of production are a way for the few to keep the masses of people in dependence." (84)