The First World War Peace Settlement

In September 1918, David Lloyd George, established a National Election Committee. As a result of the First World War a general election had not been held for over eight years. The passing of the 1918 Representation of the People Act dramatically increased the number of people who could vote. All men over twenty-one now had the vote, previously, property qualifications had barred 40 per cent of them from taking part in elections. "Female householders aged over thirty were also granted the vote, though this left women without property (including most domestic servants) and those in their twenties disenfranchised." (1) These changes almost trebled the size of the electorate. "Two million more men and six million women, five million of them married." (2)

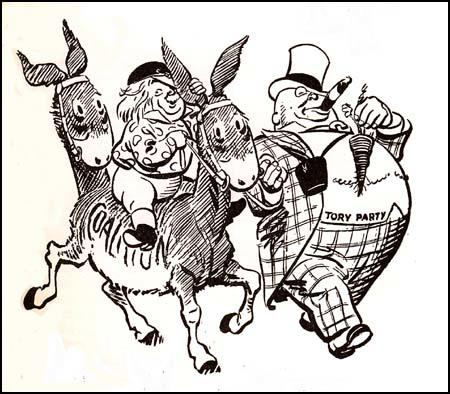

Lloyd George had lost the support of most of the Liberal Party members of the House of Commons. They had followed their leader, H. H. Asquith onto the opposition benches in December, 1916. Lloyd George realised that the only way he could hold on to power would be in a coalition government with the Conservative Party. This idea was appealing to Tory leaders as its members were divided over the issue of tariff reform. (3)

In a letter written in May, 1918, Andrew Bonar Law, explained to Arthur Balfour that "our party, on the old lines, will never have any future in this country". He suggested that unless they accepted Lloyd George's leadership, the general election might destroy the party. Bonar Law went on to argue that Lloyd George would have the same impact on the Conservative Party when Joseph Chamberlain and the Liberal Unionists joined in 1886. Lloyd George "would have the same attitude towards the Conservatives as Joe Chamberlain - with the difference that he would be leader of it (the government)... he brings to his new party fresh blood and extended appeal". (4)

Lloyd George urged the Labour Party to stay in the coalition during the general election. Its leader, Arthur Henderson, rejected the idea. In May 1915, Henderson had become the first member of the party to hold a Cabinet post when Asquith invited him to join his coalition government. However, he resigned in August, 1917, over the issue of peace negotiations. Henderson also wanted to offer the public a clear socialist programme. George Barnes, disagreed with Henderson on this issue and remained as as Minister of Pensions. (5)

By the 8th November, workers councils took power in virtually every major town and city in Germany. This included Bremen, Cologne, Munich, Rostock, Leipzig, Dresden, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Nuremberg. Theodor Wolff, writing in the Berliner Tageblatt: "News is coming in from all over the country of the progress of the revolution. All the people who made such a show of their loyalty to the Kaiser are lying low. Not one is moving a finger in defence of the monarchy. Everywhere soldiers are quitting the barracks." (6)

The German Social Democratic Party (SDP) in the Reichstag demanded the resignation of Kaiser Wilhem II. When that was refused, they resigned from the German parliament and called for a general strike throughout Germany. In Munich, Kurt Eisner, the leader of the Independent Socialist Party, declared the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic. Later that day, in order to stop the spread of the revolution, the German government agreed to surrender. On 9th November, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated and fled to Holland. At 5 a.m. on 11th November, 1918, representatives of the German government signed the armistice. It came into force at 11 a.m. (7)

1918 General Election

David Lloyd George was determined to have a general election as soon as possible. King George V wanted the election to be delayed until the public bitterness towards Germany and the desire for revenge had faded, but Lloyd George insisted on going to the country in the "warm after-glow of victory". It was announced that the 1918 General Election would take place on 12th December. (8)

The First World War had made respectable both government intervention in the economy and public ownership of some essential industries. Alfred Milner described these policies as "war socialism". David Lloyd George believed that this marked a change in the way the economy was organised and wanted to make this one of the main issues of the campaign as he feared the "socialist message" of the Labour Party might be popular with the public. Lloyd George agreed with the left-wing economist, J. A. Hobson, who believed that "The war has advanced state socialism by half a century". (9)

David Lloyd George did a deal with Arthur Bonar Law that the Conservative Party would not stand against Liberal Party members who had supported the coalition government and who had voted for him in the Maurice Debate. It was agreed that the Conservatives could then concentrate their efforts on taking on the Labour Party and the official Liberal Party that supported their former leader, H. H. Asquith. The secretary to the Cabinet, Maurice Hankey, commented: "My opinion is that the P.M. is assuming too much the role of a dictator and that he is heading for very serious trouble." (10)

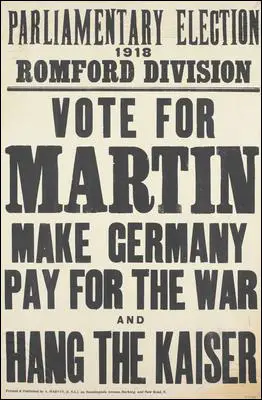

Lloyd George ran a campaign that questioned the patriotism of Labour candidates. This included Arthur Henderson, the leader of the Labour Party who had served in the government as Minister without Portfolio. Henderson's crime was that he did not call for the Kaiser to be hanged and for Germany to pay the full cost of the war. One of his opponents, James Andrew Seddon, the former President of the Trade Union Congress, and now a National Democratic Labour Coalition candidate, commented: "Mr Henderson was very sore because he was being labelled a pacifist. He might not be a pacifist but he had his foot on the slippery slope." (11)

According to Duff Cooper, Lloyd George feared his tactics were not working and he asked the the main newspaper barons, Lord Northcliffe, Lord Rothermere and Lord Beaverbrook, for help in his propaganda campaign. (12) They arranged for candidates to be sent telegrams that demanded: "For the guidance of your constituency will you kindly state whether, if elected, you will support the following: (i) Punishment of the Kaiser (ii); Full payment for the war by Germany (iii); The expulsion from the British isles of all Enemy Aliens." (13)

In every issue of The Daily Mail, Northcliffe he insisted on the hanging of Kaiser Wilhelm II and and Germany paying the full cost of the war. However, he wrote to George Riddell that he would not use his newspapers and personal influence to "support a new Government elected at the most critical period of the history of the British nations" unless he knew "definitely and in writing" and could approve "the personal constitution of the Government". When Riddell passed along this demand for the names of his prospective ministers to Lloyd George, he replied that he would "give no undertaking as to the constitution of the Government and would not dream of doing such a thing." (14)

Lloyd George told Northcliffe he could "go to hell". One friend remarked: "Each described the other as impossible and intolerable. They were both very tired men and had been getting on one another's nerves for some time." (15) Without the full support of Northcliffe, Lloyd George, arranged for Sir Henry Dalziel and a group of businessmen, who he bribed with the offer of honours and titles, to purchase The Daily Chronicle for £1.6 million. Previously, the newspaper had supported H. H. Asquith and had been highly critical of Lloyd George during the Maurice Debate. The newspaper gave its full support to Lloyd George during the 1918 General Election. (16)

David Lloyd George argued during the campaign that he was the "man who won the war" and he was "going to make Britain a fit country for heroes to live in." Although he told Winston Churchill in private that he was going to urge the execution of the Kaiser he left his fellow candidates to call for him to be hanged. The government minister, Eric Geddes, promised to squeeze Germany "until the pips squeak". In reply to those Labour politicians who called for a fair peace agreement that would prevent further wars, Lloyd George responded by calling them "extreme pacifist Bolsheviks". (17)

The General Election results was a landslide victory for David Lloyd George and the Coalition government: Conservative Party (382); Coalition Liberal (127), National Labour Coalition (4) and Coalition National Democrats (9) . The Labour Party won only 57 seats and lost most of its leaders including Arthur Henderson, Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, George Lansbury and Fred Jowett. The Liberal Party returned 36 seats and its leader H. H. Asquith was defeated at East Fife. (18)

German Revolution

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner, a member of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) established a Socialist Republic in Bavaria. Several leading socialists arrived in the city to support the new regime. This included Erich Mühsam, Ernst Toller, Otto Neurath, Silvio Gesell and Ret Marut. Eisner also wrote to Gustav Landauer inviting him to Munich: "What I want from you is to advance the transformation of souls as a speaker." Landauer became a member of several councils established to both implement and protect the revolution. (19)

Chancellor, Max von Baden, handed power over to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party. At a public meeting, one of Ebert's most loyal supporters, Philipp Scheidemann, finished his speech with the words: "Long live the German Republic!" He was immediately attacked by Ebert, who was still a strong believer in the monarchy: "You have no right to proclaim the republic." (20)

Karl Liebknecht climbed to a balcony in the Imperial Palace and made a speech: "The day of Liberty has dawned. I proclaim the free socialist republic of all Germans. We extend our hand to them and ask them to complete the world revolution. Those of you who want the world revolution, raise your hands." It is claimed that thousands of hands rose up in support of Liebknecht. (21)

Ebert established the Council of the People's Deputies, a provisional government consisting of three delegates from the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and three from the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD). Liebknecht was offered a place in the government but he refused, claiming that he would be a prisoner of the non-revolutionary majority. A few days later Ebert announced elections for a Constituent Assembly to take place on 19th January, 1918. Under the new constitution all men and women over the age of 20 had the vote. (22)

As a believer in democracy, Rosa Luxemburg assumed that her party, the Spartacus League, would contest these universal, democratic elections. However, other members were being influenced by the fact that Lenin had dispersed by force of arms a democratically elected Constituent Assembly in Russia. Luxemburg rejected this approach and wrote in the party newspaper: "The Spartacus League will never take over governmental power in any other way than through the clear, unambiguous will of the great majority of the proletarian masses in all Germany, never except by virtue of their conscious assent to the views, aims, and fighting methods of the Spartacus League." (23)

On 1st January, 1919, at a convention of the Spartacus League, Luxemburg was outvoted on this issue. As Bertram D. Wolfe has pointed out: "In vain did she (Luxemburg) try to convince them that to oppose both the Councils and the Constituent Assembly with their tiny forces was madness and a breaking of their democratic faith. They voted to try to take power in the streets, that is by armed uprising. Almost alone in her party, Rosa Luxemburg decided with a heavy heart to lend her energy and her name to their effort." (24)

In the weeks that followed the war Emil Eichhorn was appointed head of the Police Department in Berlin. As Rosa Levine pointed out: "A member of the Independent Socialist Party and a close friend of the late August Bebel, he enjoyed great popularity among revolutionary workers of all shades for his personal integrity and genuine devotion to the working class. His position was regarded as a bulwark against counter-revolutionary conspiracy and was a thorn in the flesh of the reactionary forces." (25)

On 4th January, 1919, Friedrich Ebert, ordered the removal of Emil Eichhorn, as head of the Police Department. Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982), has argued: "The Berlin workers greeted the news that Eichhorn had been dismissed with a huge wave of anger. They felt he was being dismissed for siding with them against the attacks of right wing officers and employers. Eichhorn responded by refusing to vacate police headquarters. He insisted that he had been appointed by the Berlin working class and could only be removed by them. He would accept a decision of the Berlin Executive of the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils, but no other." (26)

The Spartacus League published a leaflet that claimed: "The Ebert-Scheidemann government intends, not only to get rid of the last representative of the revolutionary Berlin workers, but to establish a regime of coercion against the revolutionary workers." It is estimated that over 100,000 workers demonstrated against the sacking of Eichhorn the following Sunday in "order to show that the spirit of November is not yet beaten." (27)

The leaders of the Spartacus League were unanimous that an uprising must be avoided at all costs. Paul Levi later reported: "The members of the leadership were unanimous; a government of the proletariat would not last more than a fortnight... It was necessary to avoid all slogans that might lead to the overthrow of the government at this point. Our slogan had to be precise in the following sense: lifting of the dismissal of Eichhorn, disarming of the counter-revolutionary troops, arming of the proletariat." (28)

Karl Liebknecht and Wilhelm Pieck published a leaflet calling for a revolution. "The Ebert-Scheidemann government has become intolerable. The undersigned revolutionary committee, representing the revolutionary workers and soldiers, proclaims its removal. The undersigned revolutionary committee assumes provisionally the functions of government." Karl Radek, had been sent by Lenin, to encourage a revolution, later commented that Rosa Luxemburg was furious with Liebknecht and Pieck for getting carried away with the idea of establishing a revolutionary government." (29)

Although massive demonstrations took place, no attempt was made to capture important buildings. On 7th January, Luxemburg wrote in the Die Rote Fahne: "Anyone who witnessed yesterday's mass demonstration in the Siegesalle, who felt the magnificent mood, the energy that the masses exude, must conclude that politically the proletariat has grown enormously through the experiences of recent weeks.... However, are their leaders, the executive organs of their will, well informed? Has their capacity for action kept pace with the growing energy of the masses?" (30)

Friedrich Ebert, Germany's new chancellor, now called in the German Army and the Freikorps to bring an end to the rebellion. They were armed with machine-guns and armoured cars and demonstrators were killed in their hundreds. Artillery was used to blow the front off the police headquarters before Eichhorn's men abandoned resistance. "Little quarter was given to its defenders, who were shot down where they were found. Only a few managed to escape across the roofs." (31)

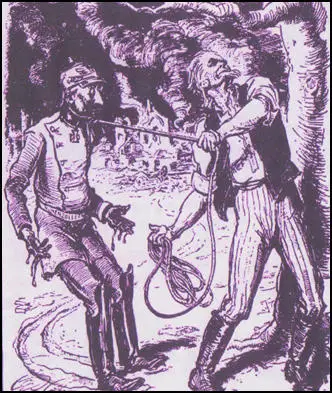

By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, who refused to flee the city, and were captured on 16th January and taken to the Freikorps headquarters. "After questioning, Liebknecht was taken from the building, knocked half conscious with a rifle butt and then driven to the Tiergarten where he was killed. Rosa was taken out shortly afterwards, her skull smashed in and then she too was driven off, shot through the head and thrown into the canal." (32)

Vorwärts, the newspaper owned by the German Social Democrat Party reported the following day: Vorwärts has the honour of announcing in advance of all other papers that Karl Liebknecht had been "shot while trying to escape" and Rosa Luxemburg was "killed by the people". (33)

The elections for the National Assembly took place on 19th January 1919. The turnout rate was 83%. Over 90% of the women eligible voted. The result was as follows: German Social Democrat Party (38.72%), Independent Social Democratic Party (5.23%), German Democratic Party (21.62%), German National People's Party (17.81%) and German People's Party (4.51).

Russian Civil War

Despite the prevailing disorders and confusion, thirty-six million people in Russia cast their secret ballots in parts of the country normal enough to hold elections. In most of the large centers of population, the voting was conducted under Bolshevik auspices. Yet twenty-seven of the thirty-six million votes went to other parties. A total of 703 candidates were elected to the Constituent Assembly in November, 1917. This included Socialist Revolutionaries (299), Bolsheviks (168), Mensheviks (18) and Constitutional Democratic Party (17).

The Constituent Assembly opened on 18th January, 1918. When the Assembly refused to support the programme of the new Soviet Government, the Bolsheviks walked out in protest. The following day, Lenin announced that the Constituent Assembly had been dissolved. Soon afterwards all opposition political groups, including the Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and the Constitutional Democratic Party, were banned in Russia.

These groups now joined forces to form the White Army. Others who joined included landowners who had lost their estates, factory owners who had their property nationalized, devout members of the Russian Orthodox Church who objected to the government's atheism and royalists who wanted to restore the monarchy.

The White Army initially had success in the Ukraine where the Bolsheviks were unpopular. The main resistance came from Nestor Makhno, the leader of an Anarchist army in the area. Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, led the Red Army and gradually pro-Bolsheviks took control of the Ukraine. By February, 1918, the Whites held no major areas in Russia.

Lenin appointed Leon Trotsky as commissar of war and was sent to rally the Red Army in the Volga. Trotsky proved to be an outstanding military commander and Kazan and Simbirsk were recaptured in September, 1918. The following month he took Samara but the White Army did make progress in the south when General Anton Denikin took control of the Kuban region and General Peter Wrangel began to advance up the Volga.

The main threat to the Bolshevik government came from General Nikolai Yudenich. In October, 1918, he captured Gatchina, only 50 kilometres from Petrograd. Leon Trotsky arrived to direct the defence of the capital. Red Guard units were established amongst industrial workers and the rail network was used to bring troops from Moscow. Outnumbered, Yudenich ordered his men to retreat and headed for Estonia. To help the White Army, troops from Britain, France, Japan and the United States were sent into Russia. By December, 1918, there were 200,000 foreign soldiers supporting the anti-Bolshevik forces.

The Red Army continued to grow and now had over 500,000 soldiers in its ranks. This included over 40,000 officers who had served under Nicholas II. This was an unpopular decision with many Bolsheviks who feared that given the opportunity, they would betray their own troops. Trotsky tried to overcome this problem by imposing a strict system of punishment for those who were judged to be disloyal.

The Versailles Peace Treaty

When the Armistice was signed on 11th November, 1918, it was agreed that there would be a Peace Conference held in Paris to discuss the post-war world. Opened on 12th January 1919, meetings were held at various locations in and around Paris until 20th January, 1920.

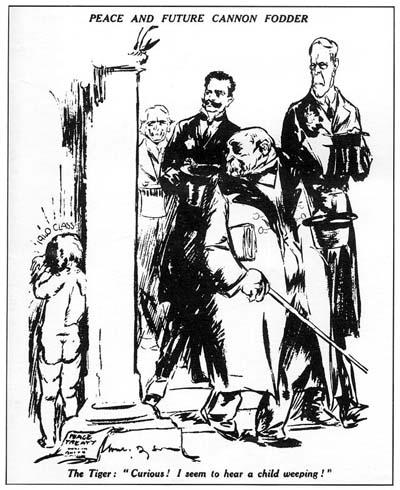

Leaders of 32 states representing about 75% of the world's population, attended. However, negotiations were dominated by the five major powers responsible for defeating the Central Powers: the United States, Britain, France, Italy and Japan. Important figures in these negotiations included Georges Clemenceau (France) David Lloyd George (Britain), Vittorio Orlando (Italy), and Woodrow Wilson (United States).

Wilson wanted to the peace to be based on the Fourteen Points published in October 1918. Lloyd George was totally opposed to several of the points. This included Point II "Absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas, outside territorial waters, alike in peace and in war, except as the seas may be closed in whole or in part by international action for the enforcement of international covenants." Lloyd George saw this as undermining the country's ability to protect the British Empire.

Another issue that worried Lloyd George was Point III: "The removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers and the establishment of an equality of trade conditions among all the nations consenting to the peace and associating themselves for its maintenance." His government was split on the subject. Some favoured a system where tariffs were placed on countries outside the British Empire. Lloyd George would also have difficulty in delivering Point IV. "Adequate guarantees given and taken that national armaments will be reduced to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety."

Seven of Wilson's points demanded or implied support for "autonomous development" or "self-determination". For example, Point V: "A free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the Government whose title is to be determined." This was an attempt to undermine the British Empire. (34)

These measures were also opposed by Georges Clemenceau. He told Lloyd George that if he accepted what Wilson proposed, he would have serious problems when he returned to France. "After the millions who have died and the millions who have suffered, I believe - indeed I hope - that my successor in office would take me by the nape of the neck and have me shot." (35)

While the discussions were taking place, the Allies continued the naval blockade of Germany. It is estimated that by December, 1918, there were 763,000 civilian famine related deaths. (36) Robert Smillie, the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB), in June, 1919, issued a statement condemning the blockade claiming that another 100,000 German civilians had died since the armistice. (37)

David Lloyd George admitted that the blockade was killing German civilians and was fermenting revolution, but thought it necessary in order to force Germany to sign the peace treaties: "The mortality among women, children and the sick is most grave and sickness, due to hunger, is spreading. The attitude of the population is becoming one of despair and people feel that an end by bullets is preferable to death by starvation." (38)

Ulrich Brockdorff-Rantzau, the leader of the German delegation, made a speech attacking the blockade. "Crimes in war may not be excusable, but they are committed in the struggle for victory in the heat of passion which blunts the conscience of nations. The hundreds of thousands of non-combatants who have perished since November 11 through the blockade were killed with cold deliberation after victory had been won and assured to our adversaries." (39)

Clemenceau and Lloyd George both hated each other. Clemenceau believed that Lloyd George knew nothing about the world beyond Great Britain, lacked a formal education and "was not an English gentleman". Lloyd George thought Clemenceau a "disagreeable and bad-tempered old savage" who, despite his large head, "had no dome of benevolence, reverence or kindliness". (40) Lloyd George told Edward House, a member of the USA's delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, that "he had to have a plausible reason for having fooled the British people about the questions of war costs, reparations and what not... Germany could not pay anything like the indemnity which the French demanded." (41)

David Lloyd George put in a claim for £25 billion of reparations at the rate of £1.2 billion a year. Clemenceau wanted £44 billion, whereas Wilson said that all Germany could afford was £6 billion. On 20th March 1919, Lloyd George explained to Wilson that it would be difficult to "disperse the illusions which reign in the public mind". He had of course been partly responsible for this viewpoint. He was especially worried about having to "face up" to the "400 Members of Parliament who have sworn to exact the last farthing of what is owing to us." (42)

Lloyd George argued that Germany should pay the costs of widows' and disability pensions, and compensation for family separations. John Maynard Keynes, an economist who was the chief Treasury representative of the British delegation, was totally opposed to the idea. (43) He argued that if reparations were set at a crippling level the banking system, certainly of Europe and probably of the world, would be in danger of collapse. (44) Lloyd George replied: "Logic! Logic! I don't care a damn for logic. I am going to include pensions." (45)

Philip Kerr, 11th Marquess of Lothian, also advised Lloyd George against demanding too much from Germany: "You may strip Germany of her colonies, reduce her armaments to a mere police force and her navy to that of a third rate power, all the same if she feels that she has been unjustly treated in the peace of 1919, she will find means of exacting retribution from her conquerors... The greatest danger that I see in the present situation is that Germany may throw in her lot with Bolshevism and place her resources, her brains, her vast organising powers at the disposal of the revolutionary fanatics whose dream is to conquer the world for Bolshevism by force of arms." (46)

When it was rumoured that Lloyd George was willing to do a deal closer to the £6 billion than the sum proposed by the French, The Daily Mail began a campaign against the Prime Minister. This included publishing a letter signed by 380 Conservative backbenchers demanding that Germany pay the full cost of the war. "Our constituents have always expected and still expect that the first edition of the peace delegation would be, as repeatedly stated in your election pledges, to present the bill in full, to make Germany acknowledge the debt and then discuss ways and means of obtaining payment. Although we have the utmost confidence in your intentions to fulfil your pledges to the country, may we, as we have to meet innumerable inquiries from our constituents, have your renewed assurances that you have in no way departed from your original intention." (47)

Lloyd George made a speech in the House of Commons where he argued that it was wrong to suggest that he was willing to accept a lower figure. He ended his speech with an attack on Lord Northcliffe, who he accused of seeking revenge for his exclusion from the government. "Under these conditions I am prepared to make allowance, but let me say that when that kind of diseased vanity is carried to the point of sowing dissension between great allies whose unity is essential to the peace of the world... then I say, not even that kind of disease is a justification for so black a crime against humanity." (48)

Negotiations continued in Paris over the level of reparations. The Australian prime minister, William Hughes, joined the French in claiming the whole cost of the war, his argument being that the tax burden imposed on the Allies by the German aggression should be regarded as damage to civilians. He estimated the cost of this was £25 billion. John Foster Dulles, commented that in his opinion, Germany should only pay about £5 billion. Faced with the possibility of an American veto, the French abandoned their claims to war costs, being impressed by Dulles's argument that, having suffered the most damage, they would get the largest share of reparations. (49)

David Lloyd George eventually agreed that he been wrong to demand such a large figure and told Dulles he "would have to tell our people the facts". John Maynard Keynes suggested to Edwin Montagu that whereas Germany should be required to "render payment for the injury she has caused up to the limit of her capacity" but it was "impossible at the present time to determine what her capacity was, so that the fixing of a definite liability should be postponed." (50)

Keynes explained to Jan Smuts that he believed the Allies should take a new approach to negotiations: "This afternoon... Keynes came to see me and I described to him the pitiful plight of Central Europe. And he (who is conversant with the finance of the matter) confessed to me his doubt whether anything could really be done. Those pitiful people have little credit left, and instead of getting indemnities from them, we may have to advance them money to live." (51)

On 28th March, 1919, Keynes warned Lloyd George about the possible long-term economic problems of reparations. "I do not believe that any of these tributes will continue to be paid, at the best, for more than a very few years. They do not square with human nature or march with the spirit of the age." He also thought any attempt to collect all the debts arising from the First World War would poison, and perhaps destroy, the capitalist system. (52)

Keynes argued that it was in the best interest of the future of capitalism and democracy for the Allies to deal swiftly with the food shortages in Germany: "A proposal which unfolds future prospects and shows the peoples of Europe a road by which food and employment and orderly existence can once again come their way, will be a more powerful weapon than any other for the preservation from the dangers of Bolshevism of that order of human society which we believe to be the best starting point for future improvement and greater well-being." (53)

Eventually it was agreed that Germany should pay reparations of £6.6 billion (269bn gold marks). Keynes was appalled and considered that the figure should be below £3 billion. He wrote to Duncan Grant: "I've been utterly worn out, partly by incessant work and partly by depression at the evil round me... The Peace is outrageous and impossible and can bring nothing but misfortune... Certainly if I were in the Germans' place I'd die rather than sign such a Peace... If they do sign, that will really be the worst thing that could happen, as they can't possibility keep some of the terms, and general disorder and unrest will result everywhere. Meanwhile there is no food or employment anywhere, and the French and Italians are pouring munitions into Central Europe to arm everyone against everyone else... Anarchy and Revolution is the best thing that can happen, and the sooner the better." (54)

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28th June 1919. Keynes wrote to Lloyd George explaining why he was resigning: "I can do no more good here. I've on hoping even though these last dreadful weeks that you'd find some way to make of the Treaty a just and expedient document. But now it's apparently too late. The battle is lost. I leave the twins to gloat over the devastation of Europe, and to assess to taste what remains for the British taxpayer." (55)

Eventually five treaties emerged from the Conference that dealt with the defeated powers. The five treaties were named after the Paris suburbs of Versailles (Germany), St Germain (Austria), Trianon (Hungary), Neuilly (Bulgaria) and Serves (Turkey). These treaties imposed territorial losses, financial liabilities and military restrictions on all members of the Central Powers.

The main terms of the Versailles Treaty were:

(1) The surrender of all German colonies as League of Nations mandates.

(2) The return of Alsace-Lorraine to France.

(3) Cession of Eupen-Malmedy to Belgium, Memel to Lithuania, the Hultschin district to Czechoslovakia.

(4) Poznania, parts of East Prussia and Upper Silesia to Poland.

(5) Danzig to become a free city;

(6) Plebiscites to be held in northern Schleswig to settle the Danish-German frontier.

(7) Occupation and special status for the Saar under French control.

(8) Demilitarization and a fifteen-year occupation of the Rhineland.

(9) German reparations of £6,600 billion.

(10) A ban on the union of Germany and Austria.

(11) An acceptance of Germany's guilt in causing the war.

(12) Provision for the trial of the former Kaiser and other war leaders.

(13) Limitation of Germany's army to 100,000 men with no conscription, no tanks, no heavy artillery, no poison-gas supplies, no aircraft and no airships;

(14) The German navy was allowed six pre-dreadnought battleships and was limited to a maximum of six light cruisers (not exceeding 6,100 tons), twelve destroyers (not exceeding 810 tons and twelve torpedo boats (not exceeding 200 tons) and was forbidden submarines.

Germany signed the Versailles Treaty under protest. The USA Congress refused to ratify the treaty. Many people in France and Britain were angry that there was no trial of the Kaiser or the other war leaders.