The Growth of Liberalism: 1868-1914

More than a million votes were cast in the 1868 General Election. This was nearly three times the number of people who voted in the previous election. The Liberals won 387 seats against the 271 of the Conservatives. Robert Blake believes the Irish issue was an important factor in Gladstone's victory. "Gladstone could not have selected a better issue on which to unify his own party and divide his opponents". The Liberals did especially well in the cities because of the "existence of a large Irish immigrant population". (1)

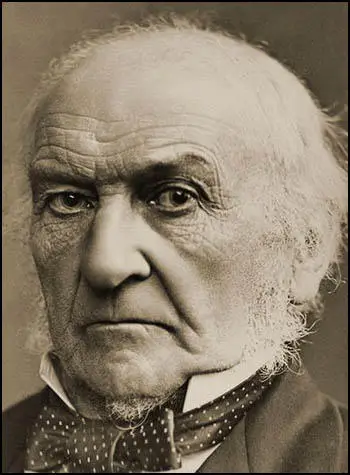

William Gladstone decided to make changes in the law which said that all Irishmen had to pay tithes to the Established Church. As he pointed out, as around 90% of the population were Catholics, it was unfair that this money went to the Protestant Church. He announced that in future the Protestant Church of Ireland would have to pay for itself out of what its members gave it. Protestants held protest meetings and Gladstone was described as "a traitor to his Queen, his country and his God". (2)

The Conservatives in the House of Lords resisted the Irish Church Bill, forcing a compromise on the financial terms but without rejecting it in principle. This was followed by an Irish Land Bill in 1870. "The fact of the passing of the bill was important, but its complexity bewildered as much as appealed; it alarmed the propertied classes but did not gain the sort of enthusiastic Irish response of the church bill a year earlier". (3)

After the passing of the 1867 Reform Act, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Robert Lowe, remarked that the government would now "have to educate our masters." Gladstone favoured the maintenance of the existing church schools, with the state providing ancillary board schools. He wanted to end church schools but realised that he would never get the legislation past the House of Lords.

The 1870 Education Act, drafted by William Forster stated: (a) the country would be divided into about 2,500 school districts; (b) School Boards were to be elected by ratepayers in each district; (c) the School Boards were to examine the provision of elementary education in their district, provided then by Voluntary Societies, and if there were not enough school places, they could build and maintain schools out of the rates; (d) the school Boards could make their own by-laws which would allow them to charge fees or, if they wanted, to let children in free. As a consequence of this legislation, spending by the state on education more than doubled. (4)

William Gladstone had a difficult relationship with Queen Victoria, who objected to some of the choices for membership of his cabinet. Worried by the growth in republicanism in Britain, he urged the near-reclusive Victoria to resume official duties. The queen resented Gladstone's tone, and apparently said that "He speaks to me as if I was a public meeting". (5)

In 1871 the government decided to impose a tax on matches. When she heard the news the Queen wrote a letter to the Chancellor of the Exchequer. "Above all it seems certain that this tax will seriously affect the manufacture and sale of matches which is said to be the sole means of support of a vast number of the very poorest people and little children, especially in London... The Queen trusts that the government will consider this proposal, and try and substitute some other which will not press upon the poor." Three days later the government decided to increase income tax instead. (6)

The previous Conservative government had established a Royal Commission on Trade Unions. Three members of the commission, Frederic Harrison, Thomas Hughes and Thomas Anson, 2nd Earl of Lichfield, refused to sign the Majority Report as they considered it hostile to trade unions. They therefore published a Minority Report where he argued that trade unions should be given privileged legal status.

The Trade Union Congress campaigned to have the Minority Report accepted by the new Liberal government. Gladstone eventually agreed and the 1871 Trade Union Act was based largely on the Minority Report. This act secured the legal status of trade unions. As a result of this legislation no trade union could be regarded as criminal because "in restraint of trade"; trade union funds were protected. Although trade unions were pleased with this act, they were less happy with the Criminal Law Amendment Act passed the same day that made picketing illegal. (7)

William Gladstone also proposed an Army Regulation Bill, which attempted to abolish the purchase of commissions. Members of the House of Commons used obstructive tactics to prevent the bill being passed. Gladstone wrote to the Queen complaining that "at the morning sitting today the House went into Committee for the tenth time on the Army Bill... the obstruction, which it is difficult to characterize by the epithets it deserves, but of which there is little doubt that it is without precedent in the present generation". (8)

Working class males now formed the majority in most borough constituencies. However, employers were still able to use their influence in some constituencies because of the open system of voting. In parliamentary elections people still had to mount a platform and announce their choice of candidate to the officer who then recorded it in the poll book. Employers and local landlords therefore knew how people voted and could punish them if they did not support their preferred candidate.

In 1872 William Gladstone removed this intimidation when his government brought in the Ballot Act which introduced a secret system of voting. Paul Foot points out: "At once, the hooliganism, drunkenness and blatant bribery which had marred all previous elections vanished. employers' and landlords' influence was still brought to bear on elections, but politely, lawfully, beneath the surface." (9)

Gladstone became very unpopular with the working-classes when his government passed the 1872 Licensing Act. This restricted the closing times in public houses to midnight in towns and 11 o'clock in country areas. Local authorities now had the power to control opening times or to become completely "dry" (banning all alcohol in the area). This led to near riots in some towns as people complained that the legislation interfered with their personal liberty.

Benjamin Disraeli, the leader of the Conservative Party, made constant attacks on Gladstone and his government. In one speech in Manchester that lasted three and quarter hours he said that the government was losing its energy. He was suggesting that Gladstone, now aged 62, was too old for the job. "As I sat opposite the ministers reminded me of one of those marine landscapes not very uncommon on the coasts of South America. You behold a row of exhausted volcanoes. Not a flame flickers from a single pallid crest". (10)

On 9th August 1873, Gladstone replaced Robert Lowe and became his own chancellor of the exchequer. Gladstone sought to regain the political initiative by a daring and dramatic financial plan: "abolition of Income Tax and Sugar Duties with partial compensation from Spirits and Death Duties". To balance the books he also needed some defence savings. However, the army and navy cabinet ministers refused. (11)

Gladstone became very disillusioned with politics and considered resigning. Gladstone wrote in his diary on 18th January, 1874: "On this day I thought of dissolution". He told some of his senior ministers, John Bright, George Leveson-Gower and George Carr Glyn of his decision. "They all seemed to approve. My first thought of it was an escape from a difficulty. I soon saw on reflection that it was the best thing in itself." (12)

In the 1874 General Election the Conservative Party won with a majority of forty-six seats. Benjamin Disraeli became Prime Minister. It was the first Conservative victory in a General Election for over 30 years. According to his biographer, Roy Jenkins, "What Gladstone greatly minded was not so much the loss of office as the sense of rejection". Gladstone wrote in his diary: "I am confident that the Conservative Party will never arrive at a stable superiority while Disraeli is at their head". (13)

William Gladstone confided in John Spencer, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, that the 1872 Licensing Act was the main cause of his defeat. "We have been swept away, literally, by a torrent of beer and gin. Next to this comes Education: that has denuded us on both sides for reasons dramatically opposite; with the Nonconformists, and with the Irish voters." (14)

Gladstone in the Wilderness

William Gladstone, had been in high office for over fifteen years and he decided to retire from leading the Liberal Party. It was with some relief when he shocked his ex-cabinet colleagues that he would "no longer retain the leadership of the liberal party, nor resume it, unless the party had settled its difficulties". (15)

Although he was sixty-four years old he was in very good health: "He was fit, spare, and sprightly. He stood 5 feet 10½ inches and had an abnormally large head, with eagle-like eyes. He had accidentally shot off his left forefinger while shooting in September 1842 and always wore a fingerstall. A trim 11 stone 11 pounds, he ate and drank moderately, and did not smoke. Remarkable physical resilience made him... one of the fittest of prime ministers. Tree-felling... was a demanding and invigorating activity; it kept him fit and spry. In September 1873 he walked 33 miles in the rain through the Cairngorm mountains from Balmoral to Kingussie." (16)

Gladstone retained his seat in the House of Commons but spent most of his spare time writing. In November 1874, he published the pamphlet The Vatican Decrees in their Bearing on Civil Allegiance, attacking the idea of Papal infallibility that had been confirmed by Pius IX in 1870. Gladstone claimed that this placed Catholics in Britain in a dilemma over conflicts of loyalty to the Crown. He urged them to reject papal infallibility as they had opposed the Spanish Armada of 1588. The pamphlet was very popular and sold 150,000 copies in a couple of months. (17)

In another pamphlet Vaticanism: an Answer to Reproofs and Replies (February, 1875) he described the Catholic Church as "an Asian monarchy: nothing but one giddy height of despotism, and one dead level of religious subservience". He further claimed that the Pope wanted to destroy the rule of law and replace it with arbitrary tyranny, and then to hide these "crimes against liberty beneath a suffocating cloud of incense". (18)

During this period he became very friendly with Laura Thistlethwayte. The daughter of Captain R. H. Bell in Newry, was rumoured to have been a prostitute in Dublin before marrying the wealthy Augustus Frederick Thistlethwayte, a retired army captain and son of Thomas Thistlethwayte, the former M.P. for Hampshire. At their first meeting he knew enough about her to admit later that he had been drawn to her as a "sheep or lamb that had been astray... that had come back to the Shepherd's Fold, and to the Father's arms". (19)

Colin Matthew, one of Gladstone's main biographers, has pointed out: "Unlike the prostitutes whom Gladstone energetically continued throughout his premiership to attempt to redeem, Laura Thistlethwayte was already saved from sin and was converted. Gladstone was at first intrigued and soon obsessed with her tale... This was in effect a platonic extra-marital affair... On the third finger of his right hand he often wore a ring given him by Laura Thistlethwayte." (20)

There was considerable amount of gossip about Gladstone's behaviour. Queen Victoria told Disraeli that Gladstone was mad in dining with the "notorious" Mrs. Thistlethwayte. (21) Edward Stanley, 15th Earl of Derby, wrote: "Strange story of Gladstone frequenting the company of a Mrs. Thistlethwayte, a kept woman in her youth, who induced a foolish person with a large fortune to marry her... her beauty is her attraction to Gladstone and it is characteristic of him to be indifferent to scandal. I can scarcely believe the report that he is going to pass a week with her and her husband at their country house - she not being visited or received in society. (22)

As the prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli now had the opportunity to the develop the ideas that he had expressed when he was leader of the Young England group in the 1840s. Social reforms passed by the Disraeli government included: the Factory Act (1874) and the Climbing Boys Act (1875), Artisans Dwellings Act (1875), the Public Health Act (1875), the Pure Food and Drugs Act (1875). Disraeli also kept his promise to improve the legal position of trade unions. The Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act (1875) allowed peaceful picketing and the Employers and Workmen Act (1878) enabled workers to sue employers in the civil courts if they broke legally agreed contracts. (23)

Early in his career Benjamin Disraeli was not a strong enthusiast for building up the British Empire and had described colonies as "millstones around our neck" and had argued that the Canadians should "defend themselves" and that British troops should be withdrawn from Africa. However, once he became prime-minister he changed his view on the subject. He was especially interested in India, with its population of over 170 million. It was also an outlet for British goods and a source of valuable imports such as raw cotton, tea and wheat. It is possible that he saw the Empire as an "issue on which to damage his opponents by impugning their patriotism". (24)

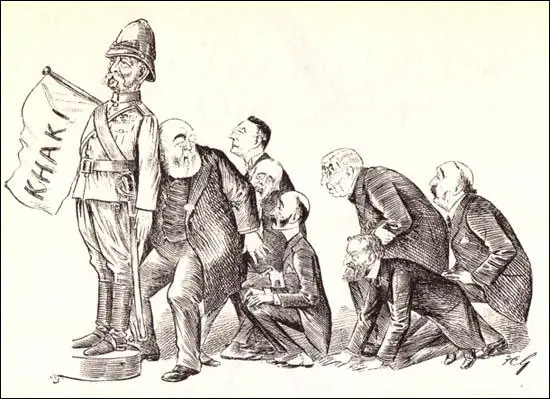

In one speech Disraeli attacked Liberals as being people who were not committed to the British Empire: "Gentlemen, there is another and second great object of the Tory party. If the first is to maintain the institutions of the country, the second is, in my opinion, to uphold the empire of England. If you look to the history of this country since the advent of Liberalism - forty years ago - you will find that there has been no effort so continuous, so subtle, supported by so much energy, and carried on with so much ability and acumen, as the attempts of Liberalism to effect the disintegration of the empire of England." (25)

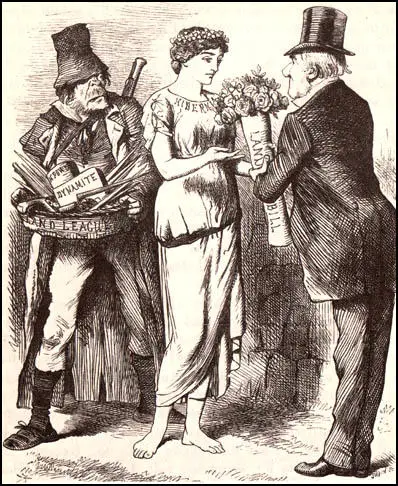

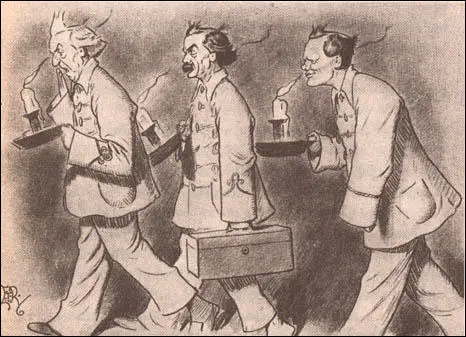

Exchanging Gifts, Punch Magazine (1876)

Benjamin Disraeli got on very well with Queen Victoria. She approved of Disraeli's imperialist views and his desire to make Britain the most powerful nation in the world. In May, 1876 Victoria agreed to his suggestion that she should accept the title of Empress of India. The title was said to be un-English and the proposal of the measure also seemed to suggest an unhealthily close political relationship between Disraeli and the Queen. The idea was rejected by Gladstone and other leading figures in the Liberal Party. (26)

Bulgarian Horrors

In May 1876 it was reported that Turkish troops had murdered up to 7,000, Orthodox Christians in the Balkans. Gladstone was appalled by these events and on 6th September he published Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East (1876). He sent a copy to Benjamin Disraeli who described the pamphlet as "vindictive and ill-written... indeed in that respect of all the Bulgarian horrors perhaps the greatest." (27)

The initial print run of 2,000 sold out in two days. Several reprints took place and eventually over 200,000 copies of the pamphlet were sold. On 9th September, Gladstone addressed an audience of 10,000 at Blackheath on the subject and became the leader of the "popular front of moral outrage". Gladstone stated that "never again shall the hand of violence be raised by you, never again shall the flood-gates of lust be open to you, never again shall the dire refinements of cruelty be devised by you for the sake of making mankind miserable." (28)

William Gladstone's approach was in stark contrast to what has been called "Disraeli's sardonic cynicism". Robert Blake has argued that the conflict between Gladstone and Disraeli "injected a bitterness into British politics which had not been seen since the Corn Law debates". (29) It has been claimed that "Gladstone developed a new form of evangelical mass politics" over this issue. (30)

William Gladstone once again became a popular politician. Historians have been unsure if this was a calculated response or an aspect of his moral convictions. "The genesis of Gladstone's fervour on the issue is difficult to analyse. Was he, perhaps semi-consciously, looking for a cause for which... he could re-emerge as the dominating central figure of politics... Or was he spontaneously seized with a passionate sympathy for the sufferings of the Balkan Christian communities which left him to alternative but to erupt with his full and extraordinary force?" (31)

Benjamin Disraeli definitely believed William Gladstone was using the massacre to further his political career. He told a friend: "Posterity will do justice to that unprincipled maniac Gladstone - extraordinary mixture of envy, vindictiveness, hypocrisy and superstition; and with one commanding characteristic - whether preaching, praying, speechifying, or scribbling - never a gentleman!" (32)

Gladstone began to attack the foreign policy of the Conservative government. He attacked imperialism and warned of the dangers of a bloated empire with worldwide responsibilities which in the long run would become unsustainable. He pointed out that military spending had turned an inherited surplus of £6 million into a deficit of £8 million. As a result of these views, Prince George, Duke of Cambridge (the commander-in-chief) refused to shake Gladstone's hand when he met him. When his house was attacked by a Jingo mob on a Sunday evening, Gladstone wrote in his diary: "This is not very sabbatical". (33)

1880 General Election

In the 1880 General Election he contested the seat of Midlothian. He made eighteen important speeches. "The verbatim reporting of Gladstone's speeches ensured that they were available to every newspaper-reading household the next morning". Gladstone defeated his conservative opponent, William Montagu Douglas Scott, on 5th April 1880 by 1,579 votes to 1,368. (34)

It was a great victory for the Liberal Party who won 352 seats with 54.7% of the vote. Benjamin Disraeli resigned and Queen Victoria invited Spencer Cavendish, Lord Hartington, the official leader of the party, to become her new prime minister. He replied that the Liberal majority appeared to the nation as being a "Gladstone-created one" and that Gladstone had already told other senior figures in the party he was unwilling to serve under anybody else.

Victoria explained to Hartington that "there was one great difficulty, which was that I could not give Mr. Gladstone my confidence." She told her private secretary, Sir Henry Frederick Ponsonby: "She will sooner abdicate than send for or have any communication with that half mad firebrand who would soon ruin everything and be a dictator. Others but herself may submit to his democratic rule but not the Queen." (35)

Victoria now asked to see Granville Leveson-Gower, 2nd Earl Granville. He also refused to be prime minister, explaining that Gladstone had a "great amount of popularity at the present moment amongst the people". He also suggested that Gladstone, now aged 70, would probably retire by 1881. Victoria now agreed to appoint Gladstone as her prime minister. That night he recorded in his diary that the Queen received him "with the perfect courtesy from which she never deviates". (36)

Queen Victoria attempted to select Gladstone's cabinet ministers. He rejected this idea and appointed those who he felt would remain loyal to him. Gladstone who was described as looking "very ill and haggard, and his voice feeble" surprised the Queen by telling her that he intended to be his own Chancellor of the Exchequer. Joseph Chamberlain, the only member of the left-wing group within the Liberal Party, who was given a senior post in the government. (37)

The Liberal Party's victory owed a great deal to the increase in the number of working-class male voters. As Paul Foot has pointed out, this was not reflected in the newly formed government: "In the Cabinet of fourteen members, there were six earls (Selborne, Granville, Derby, Kimberley, Northbrook and Spencer), a marquis (Hartington), a baron (Carlingford), two baronets (Harcourt and Dilke) and only four commoners (Gladstone, Childers, Dodson and Joseph Chamberlain)." Only one working man, the trade union leader, Henry Broadhurst, joined the government as a junior minister for trade. (38)

Gladstone spent more time in the House of Commons than any other prime minister in the history of Parliament except for Stanley Baldwin: "But he (Gladstone) devoted his long hours there to the chamber, always listening, often intervening, whereas Baldwin was much more in the corridors, dining room and smoking room, alien territories to Gladstone, gossiping and absorbing atmosphere rather than directing business." (39)

Irish Land Act

Gladstone's first Irish Land Act had been a failure. He was now coming under pressure from the Land League that had been taking the law into their own hands and in the last three months of 1880, 1,696 crimes against Irish landlords took place. In February 1881 Gladstone asked Parliament to pass a Coercion Act, which meant that people suspected of crimes could be arrested and kept in jail without trial. (40)

In April 1881 Gladstone introduced his Second Land Bill in the House of Commons. It included three of the demands advocated by the Land League: (a) Fair Rents: To be decided by a court if the landlord and the tenant could not agree on what was fair. (b) Fixture of Tenure: The Tenant could stay in his farm as long as he wished, provided he paid the rent. (c) Free Sale: If a tenant left his farm he would be paid for any improvements he had made to it. Despite opposition from the House of Lords the bill became law in August 1881. (41)

Historians have been highly critical of this measure. Paul Adelman, the author of Great Britain and the Irish Question (1996) has pointed out: "Despite his masterly performance in pushing the complicated Land bill through the Commons in the summer of 1881, recent historians have argued that Gladstone again failed to face up to the economic realities of rural Ireland. For in the west of Ireland particularly, it was the lack of cultivable land rather than the problem of rents that was the fundamental problem for the smallholders." (42)

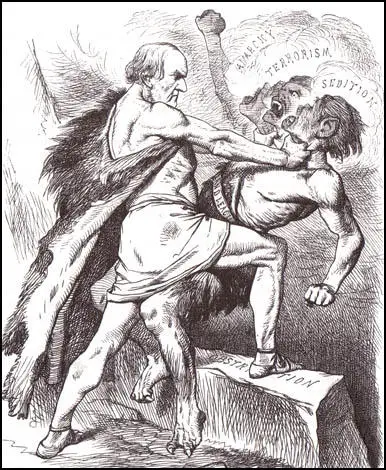

Charles Stewart Parnell, the leader of the Irish Land League, criticised several aspects of the Act (such as the exclusion of tenants in arrears from its provisions). In a speech in October 1881, Gladstone warned Parnell of taking direct action. "If there is to be fought a final conflict in Ireland between law on the one side and sheer lawlessness on the other... then I say... the resources of civilisation are not exhausted." (43) Parnell responded by denouncing the Liberal leader as "a masquerading knight errant, the pretending champion of the rights of every other nation except those of the Irish nation". (44)

Queen Victoria and William Gladstone

Queen Victoria and Gladstone were in constant conflict during his premiership. She often wrote to him complaining about his progressive policies. When he became prime minister in 1880 she warned him about the appointment of advance Radicals such as Joseph Chamberlain, Charles Wentworth Dilke, Henry Fawcett, James Stuart and Anthony Mundella, The Queen was also disappointed that Gladstone had not found a place for George Goschen, in his government, a man who she knew was strongly against parliamentary reform. (45)

In November, 1880, Queen Victoria she told him that he should be careful about making statements about future political policy: "The Queen is extremely anxious to point out to Mr. Gladstone the immense importance of the utmost caution on the part of all the Ministers but especially of himself, at the coming dinner in the City. There is such danger in every direction that a word too much might do irreparable mischief." (46) The following year she made a similar comment: "I see you are to attend a great banquet at Leeds. Let me express a hope that you will be very cautious not to say anything which could bind you to any particular measures." (47)

Gladstone's private secretary, Edward Walter Hamilton, claimed that he wrote to the Queen over a thousand times, and his letters were frequently in reply to hers. Victoria often complained about the speeches made by his most progressive cabinet ministers, Joseph Chamberlain and Charles Wentworth Dilke. Hamilton wrote to the Queen pointing out: "Your Majesty will readily believe that he (William Gladstone) has neither the time nor the eyesight to make himself acquainted by careful perusal with all the speeches of his colleagues". (48)

Hamilton believed that Victoria was jealous of Gladstone's popularity: "She (Victoria) feels, as he (Gladstone) puts it, aggrieved at the undue reverence shown to an old man of whom the public are being constantly reminded, and who goes on working for them beyond the allotted time, while H.M. is, owing to the life she leads, withdrawn from view... What he wraps up in guarded and considerate language is (to put it bluntly) jealously. She can't bear to see the large type which heads the columns in newspapers by 'Mr Gladstone's movements', while down below is in small type the Court Circular." (49)

1884 Reform Act

Gladstone's wife found the duties associated with managing a political household onerous and uninteresting and his daughter, Mary Gladstone, now aged 33 years old, played the main role as the hostess at the family residences. Susan K. Harris, the author of The Cultural Work of the Late Nineteenth-Century Hostess (2004) has pointed out: "Once Gladstone resumed office his daughter's influence would be a major attraction for many people, who saw her as a way to reach her powerful father." (50)

Mary was extremely interested in political ideas. In August 1883 she began reading Progress and Poverty, a book by Henry George. Mary wrote in her diary that the book is "supposed to be the most upsetting, revolutionary book of the age. At present Maggie and I both agree with it, and most brilliantly written it is. We had long discussions. He (her father) is reading it too." Gladstone later remarked "it is well-written but a wild book". (51)

William Gladstone continued to enjoy good health. In 1884, when he was approaching his seventy-fifth birthday, he climbed Ben Macdui, at 4300 feet the highest point in the Cairngorms, taking seven hours forty minutes to do the twenty-mile round trip. Gladstone's wife never urged him to retire from politics. One of his biographer's, Roy Jenkins, has speculated that "she probably sensed that responsibility was a better shield to his body than was rest". (52)

In 1884 Gladstone introduced his proposals that would give working class males the same voting rights as those living in the boroughs. The bill faced serious opposition in the House of Commons. The Tory MP, William Ansell Day, argued: "The men who demand it are not the working classes... It is the men who hope to use the masses who urge that the suffrage should be conferred upon a numerous and ignorant class." (53)

George Goschen had been one of the leading Liberal opponents to the 1867 Reform Act. However, he supported the 1884 Reform Act: "The argument against the enfranchisement of the working class was this - and no doubt it is a very strong argument - the power they would have in any election if they combined together on questions of class interest. We are bound not to put that risk out of sight. Well, at the last election, I carefully watched the various contests that were taking place and I am bound to admit that I saw no tendency on the part of the working classes to combine on any special question where their pecuniary interests were concerned. On the contrary, they seemed to me to take a genuine political interest in public questions ... The working classes have given proofs that they are deeply desirous to do what is right." (54)

The bill was passed by the Commons on 26th June, with the opposition did not divide the House. The Conservatives were hesitant about recording themselves in direct hostility to franchise enlargement. However, Gladstone knew he would have more trouble with the House of Lords. Gladstone wrote to twelve of the leading bishops and asked for their support in passing this legislation. Ten of the twelve agreed to do this. However, when the vote was taken the Lords rejected the bill by 205 votes to 146.

Queen Victoria thought that the Lords had every right to reject the bill and she told Gladstone that they represented "the true feeling of the country" better than the House of Commons. Gladstone told his private secretary, Edward Walter Hamilton, that if the Queen had her way she would abolish the Commons. Over the next two months the Queen wrote sixteen letters to Gladstone complaining about speeches made by left-wing Liberal MPs. (55)

The London Trades Council quickly organized a mass demonstration in Hyde Park. On 21st July, an estimated 30,000 people marched through the city to merge with at least that many already assembled in the park. Thorold Rogers, compared the House of Lords to "Sodom and Gomorrah" and Joseph Chamberlain told the crowd: "We will never, never, never be the only race in the civilized world subservient to the insolent pretensions of a hereditary caste". (56)

Queen Victoria was especially angry about the speech made by Chamberlain, who was President of the Board of Trade in Gladstone's government. She sent letters to Gladstone complaining about Chamberlain on 6th, 8th and 10th August, 1884. (57) Edward Walter Hamilton, Gladstone's private secretary replied to the Queen explaining that the Prime Minister "has neither the time nor the eyesight to make himself acquainted by careful perusal with all the speeches of his colleagues." (58)

In August 1884, William Gladstone sent a long and threatening memorandum to the Queen: "The House of Lords has for a long period been the habitual and vigilant enemy of every Liberal Government... It cannot be supposed that to any Liberal this is a satisfactory subject of contemplation. Nevertheless some Liberals, of whom I am one, would rather choose to bear all this for the future as it has been borne in the past, than raise the question of an organic reform of the House of Lords... I wish (an hereditary House of Lords) to continue, for the avoidance of greater evils... Further; organic change of this kind in the House of Lords may strip and lay bare, and in laying bare may weaken, the foundations even of the Throne." (59)

Other politicians began putting pressure on Victoria and the House of Lords. One of Gladstone's MPs advised him to "Mend them or end them." However, Gladstone liked "the hereditary principle, notwithstanding its defects, to be maintained, for I think it in certain respects an element of good, a barrier against mischief". Gladstone was also secretly opposed to a mass creation of peers to give it a Liberal majority. However, these threats did result in conservative leaders being willing to negotiate over this issue. Hamilton wrote in his diary that "the atmosphere is full of compromise". (60)

Other moderate Liberal MPs feared that if the 1884 Reform Act was not passed Britain was in danger of a violent revolution. Samuel Smith feared the development of socialist parties such as the Social Democratic Party in Germany: "In the country, the agitation has reached a point which might be described as alarming. I have no desire to see the agitation assume a revolutionary character which it would certainly assume if it continued much longer.... I am afraid that there would emerge from out of the strife a new party like the social democrats of Germany and that the guidance of parties would pass from the hands of wise statesmen into that of extreme and violent men". (61)

John Morley was one of the MPs who led the fight against the House of Lords. The Spectator reported "He (John Morley) was himself, be said, convinced that compromise was the life of politics; but the Franchise Bill was a compromise, and if the Lords threw it out again, that would mean that the minority were to govern... The English people were a patient and a Conservative people, but they would not endure a stoppage of legislation by a House which had long been as injurious in practice as indefensible in theory. If the struggle once began, it was inevitable that the days of privilege should be numbered." (62)

Left-wing members of the Liberal Party, such as James Stuart, urged Gladstone to give the vote to women. Stuart wrote to Gladstone's daughter, Mary: "To make women more independent of men is, I am convinced, one of the great fundamental means of bringing about justice, morality, and happiness both for married and unmarried men and women. If all Parliament were like the three men you mention, would there be no need for women's votes? Yes, I think there would. There is only one perfectly just, perfectly understanding Being - and that is God.... No man is all-wise enough to select rightly - it is the people's voice thrust upon us, not elicited by us, that guides us rightly." (63)

A total of 79 Liberal MPs urged Gladstone to recognize the claim of women's householders to the vote. Gladstone replied that if votes for women was included Parliament would reject the proposed bill: "The question with what subjects... we can afford to deal in and by the Franchise Bill is a question in regard to which the undivided responsibility rests with the Government, and cannot be devolved by them upon any section, however respected , of the House of Commons. They have introduced into the Bill as much as, in their opinion, it can safely carry." (64)

The bill was passed by the Commons but was rejected by the Conservative dominated House of Lords. Gladstone refused to accept defeat and reintroduced the measure. This time the Conservative members of the Lords agreed to pass Gladstone's proposals in return for the promise that it would be followed by a Redistribution Bill. Gladstone accepted their terms and the 1884 Reform Act was allowed to become law. This measure gave the counties the same franchise as the boroughs - adult male householders and £10 lodgers - and added about six million to the total number who could vote in parliamentary elections. (65)

However, this legislation meant that all women and 40% of adult men were still without the vote. According to Lisa Tickner: "The Act allowed seven franchise qualifications, of which the most important was that of being a male householder with twelve months' continuous residence at one address... About seven million men were enfranchised under this heading, and a further million by virtue of one of the other six types of qualification. This eight million - weighted towards the middle classes but with a substantial proportion of working-class voters - represented about 60 per cent of adult males. But of the remainder only a third were excluded from the register of legal provision; the others were left off because of the complexity of the registration system or because they were temporarily unable to fulfil the residency qualifications... Of greater concern to Liberal and Labour reformers... was the issue of plural voting (half a million men had two or more votes) and the question of constituency boundaries." (66)

William Gladstone: 1886-1892

In June 1885 Gladstone resigned after supporters of Irish Home Rule and the Conservative Party joined forces to defeat his Liberal government's Finance Bill. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, accepted office and formed a minority Conservative government. Gladstone continued as leader of the Liberal Party, and was confident that a general election on the new franchise and distribution being imminent, would give him back power.

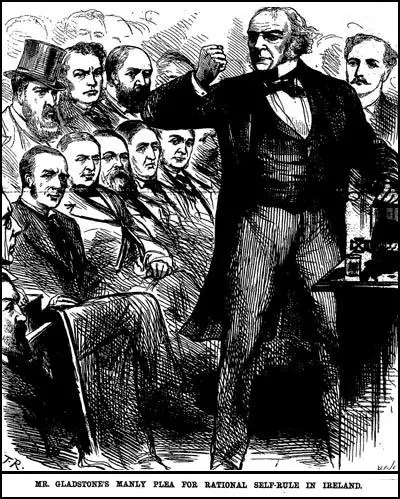

Gladstone and the Liberals won the 1885 General Election, with a majority of seventy-two over the Tories. However, the Irish Nationalists could cause problems because they won 86 seats. On 8th April 1886, Gladstone announced his plan for Irish Home Rule. Mary Gladstone Drew wrote: "The air tingled with excitement and emotion, and when he began his speech we wondered to see that it was really the same familiar face - familiar voice. For 3 hours and a half he spoke - the most quiet earnest pleading, explaining, analysing, showing a mastery of detail and a grip and grasp such as has never been surpassed. Not a sound was heard, not a cough even, only cheers breaking out here and there - a tremendous feat at his age... I think really the scheme goes further than people thought." (67)

The Home Rule Bill said that there should be a separate parliament for Ireland in Dublin and that there would be no Irish MPs in the House of Commons. The Irish Parliament would manage affairs inside Ireland, such as education, transport and agriculture. However, it would not be allowed to have a separate army or navy, nor would it be able to make separate treaties or trade agreements with foreign countries. (68)

The Conservative Party opposed the measure. So did some members of the Liberal Party, led by Joseph Chamberlain, also disagreed with Gladstone's plan. Chamberlain main objection to Gladstone's Home Rule Bill was that as there would be no Irish MPs at Westminster, Britain and Ireland would drift apart. He added that this would be amounting to the start of the break-up of the British Empire. When a vote was taken, there were 313 MPs in favour, but 343 against. Of those voting against, 93 were Liberals. They became known as Liberal Unionists. (69)

Gladstone responded to the vote by dissolving parliament rather than resign. During the 1886 General Election he had great difficultly leading a divided party. According to Colin Matthew: "So dedicated was Gladstone to the campaign that he agreed to break the habit of the previous forty years and cease his attempts to convert prostitutes, for fear, for the first time, of causing a scandal (Liberal agents had heard that the Unionists were monitoring Gladstone's nocturnal movements in London with a view to a press exposé)". (70)

In the election the number of Liberal MPs fell from 333 in 1885 to 196, though no party gained an overall majority. Gladstone resigned on 30th July. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, once again became prime minister. Queen Victoria wrote him a letter where she said she always thought that his Irish policy was bound to fail and "that a period of silence from him on this issue would now be most welcome, as well as his clear patriotic duty." (71)

William Gladstone refused to retire and continued as leader of the opposition. He wrote several articles on the subject of Home Rule and questioned the idea that the House of Lords should be able to block government legislation. Although he remained active in politics, a decline in his hearing and eyesight made life difficult. "His memory, particularly for names but also for recent events, although not for more distant ones, showed signs of fading... On the other hand his physical stamina remained formidable. He felled his last tree a few weeks before his eighty-second birthday." (72)

Gladstone had always rejected the philosophy of socialism but he became much more sympathetic to the trade union movement and supported the workers during the London Dock Strike. After their victory he gave a speech at Hawarden on 23rd September, 1889, in which he said: "In the common interests of humanity, this remarkable strike and the results of this strike, which have tended somewhat to strengthen the condition of labour in the face of capital, is the record of what we ought to regard as satisfactory, as a real social advance that tends to a fair principle of division of the fruits of industry". (73) Eugenio Biagini, in his book, Liberty, Retrenchment and Reform: Popular Liberalism in the Age of Gladstone (2008) has argued that this speech has "no parallel in the rest of Europe except in the rhetoric of the toughest socialist leaders". (74)

Prime Minister: 1892-1894

The Liberals enjoyed twelve by-election victories during the period 1886 and 1891 and Gladstone was expected to win the next election. William Stead interviewed Gladstone in April, 1892 and was surprised by the energy of the veteran politician: "Mr. Gladstone is old enough to be the grandfather of the younger race of politicians, but his courage, his faith, and his versatility, put the youngest of them to shame. It is this ebullience of youthful energy, this inexhaustible vitality, which is the admiration and the despair of his contemporaries. Surely when a schoolboy at Eton he must somewhere have discovered the elixir of life or have been bathed by some beneficent fairy in the well of perpetual youth. Gladly would many a man of fifty exchange physique with this hale and hearty octogenarian.... A splendid physical frame, carefully preserved, gives every promise of a continuance of his green old age." (75)

In the 1892 General Election held in July, Gladstone's Liberal Party won the most seats (272) but he did not have an overall majority and the opposition was divided into three groups: Conservatives (268), Irish Nationalists (85) and Liberal Unionists (77). Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, refused to resign on hearing the election results and waited to be defeated in a vote of no confidence on 11th August. Gladstone, now 84 years old, formed a minority government dependent on Irish Nationalist support. (76)

A Second Home Rule Bill was introduced on 13th February 1893. Gladstone personally took the bill through the "committee stage in a remarkable feat of physical and mental endurance". (77) After eighty-two days of debate it was passed in the House of Commons on 1st September by 43 votes (347 to 304). Gladstone wrote in his diary, "This is a great step. Thanks be to God." (78)

On 8th September, 1893, after four short days of debate, the House of Lords rejected the bill, by a vote of 419 to 41. "It was a division without precedent, both for the size of the majority and the strength of the vote. There were only 560 entitled to vote, and 82 per cent of them did did so, even though there was no incentive of uncertainty to bring remote peers to London." (79)

It is alleged that William Gladstone considered resigning and calling a new general election on the issue. However, he suspected that he could not mount a successful electoral indictment of the House of Lords on Irish Home Rule. He therefore pushed ahead with the Workmen's Compensation Act, a measure that was extremely unpopular with employers. The act dealt with the right of workers for compensation for personal injury. It replaced the Employer's Liability Act 1880, which required the injured worker the right to sue the employer and put the burden of proof on the employee. Gladstone thought that when the Lords blocked the bill he could call an election and win.

However, in December 1893, Gladstone came into conflict with his own party over the issue of defence spending. The Conservative Party began arguing for an expansion of the Royal Navy. Gladstone made it clear that he was opposed to this policy. William Harcourt, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was willing to increase naval expenditure by £3 million. John Poyntz Spencer, the First Lord of the Admiralty, agreed with Harcourt. Gladstone refused to budge on the issue and wrote that he would not "break to pieces the continuous action of my political life, nor trample on the tradition received from every colleague who has ever been my teacher" by supporting naval rearmament. (80)

Conservatives continued to block the government's legislation. After accepting the Lords' amendments to the Local Government Bill "under protest" he decided to resign. In his last speech to the House of Commons on 1st March, 1894, he suggested that the time had come to change the rules of the British Parliament so that the House of Lords would no longer have the power to refuse to pass Bills which had been passed by the House of Commons. Gladstone died, aged 89, in 1898. (81)

Herbert Henry Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith (generally known as H. H. Asquith), the second son of the two sons and three daughters of Joseph Dixon Asquith and his wife, Emily Willans Asquith, was born in Morley on 12th September 1852. His father was a wool merchant, supplying the local mills with top quality cloth from all over Europe. (82)

Asquith's biographer, Colin Matthew, has pointed out: "Two of his sisters died early, and his brother suffered a sports injury which stunted his growth; his father died when he was eight, from an intestine twisted while playing cricket. His mother was an invalid, with a heart condition and frequent bronchitis. The young Herbert Asquith soon of necessity developed the imperturbable, slightly withdrawn, self-sufficiency and good health which was his life's standby." (83)

The Asquith family were strong supporters of the Liberal Party. Asquith had a good relationship with both parents. He later described his mother as being a profoundly religious woman who was "a devoted and sagacious mother" who "made herself the companion and intimate friend of her children." (84)

After the death of his father in 1860, his grandfather, William Willans, took responsibility for the family, sending Asquith to Huddersfield College, and then in 1861 to the Fulneck Moravian School, near Leeds. He then went onto the City of London School. His mother moved to St Leonards, but Asquith remained in London and was "treated like an orphan" for the rest of his childhood. (85)

In November 1869, Asquith won a classical scholarship at Balliol College. While at Oxford University he came under the influence of Benjamin Jowett, his philosophy teacher. Asquith later commented to John Morley that Jowett's "talk is like one of those wines that have more bouquet than body." (86)

H. H. Asquith was described as being someone with "effortless superiority" while others claimed it was a disguise for shyness: "I am hedged in and hampered in these ways by a kind of native reserve, of which I am not at all proud". To another of his friends he was "a man who had a plan of life well under control" with "a remarkable power of using every gift he possessed to full capacity." (87)

Asquith was an outstanding student and eventually achieved a first-class honours degree. He also took an active role in politics and in 1874 he became president of the Oxford Union. While at university he made several important friends including Alfred Milner, Andrew C. Bradley, Thomas Herbert Warren, Charles Gore, William P. Ker, and William H. Mallock. (88)

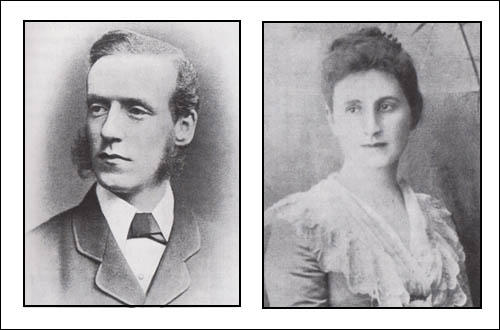

Asquith entered Lincoln's Inn to train as a barrister. He was called to the bar in June 1876. Asquith had fallen in love with Helen Melland when he had first met her at the age of fifteen in 1869. In September 1876, asked Dr. Frederick Melland for permission to marry his daughter. After a two month delay he replied: "I have the fullest conviction that your industry and ability will procure for you in due time that success in your profession which has attended you in your past career." (89)

H. H. Asquith married Helen on 23rd August 1877. He later told a friend: "Her mind was clear and strong, but it was not cut in facets and did not flash lights, and no one would call her clever or intellectual. What gave her rare quality was her character, which everyone who knew her agrees was the most selfless and unworldly that they have ever encountered. She was warm, impulsive, naturally quick-tempered, and generous almost to a fault." (90)

Over the next thirteen years Helen gave birth to five children: Raymond (1878), Herbert (1881), Arthur (1883), Violet (1887) and Cyril (1890). The couple were devoted to their children. Herbert Asquith pointed out that both his parents "allowed their children a full measure of liberty; they used the snaffle rather than the curb and their control was very elastic in nature." (91)

Asquith later wrote: "I was content with my early love, and never looked outside. So we settled down in a little suburban villa, and our children were born, and every day I went by train to the Temple, and sat and worked and dreamed in my chambers, and listened with feverish expectation for a knock on the door, hoping it might be a client with a brief. But years passed and he hardly ever came." (92)

During this period wrote regular articles for The Spectator: "These articles... show his lifelong Liberalism early and clearly defined. They reflect a staunch radicalism tempered by realism (on condition that it worked from within the Liberal Party), a hostility to radical factionalists, and an admiration for party spirit." (93) Asquith warned about the dangers of the growth of socialism, something he described as "the English extreme left". (94)

In 1885, Asquith's close friend, Richard Haldane, was elected as Liberal Party MP for East Lothian. He persuaded Asquith to apply for the vacant Liberal candidacy in the neighbouring consistency of East Fife. Asquith was a keen advocate of Home Rule and this was one of the reasons why he won his seat in the 1886 General Election with a majority of only 376. In the election the number of Liberal MPs fell from 333 in 1885 to 196, though no party gained an overall majority.

Asquith's early years as an MP were marked by intense hard work as he tried to juggle his political commitments with the need to support his growing family from his earnings at the Bar. He did not make his maiden speech until 24th March 1887. Gladstone was impressed by his contribution and invited him to dinner. Gladstone told his friends that he considered Asquith to be a future leader of the Liberal Party. Although he spoke rarely in the House of Commons he developed a reputation for political oratory. (95)

H. H. Asquith, as a good-looking and charming MP, was a much sought after dinner-party guest. Frances Horner commented: "We never thought any party complete without him." (96) In March, 1891, he found himself seated next to Margot Tennant, the vivacious twenty-seven-year-old youngest daughter of his fellow Liberal MP Sir Charles Tennant. Margot commented that she "was deeply impressed by his conversation and his clear Cromwellian face... he had a way of putting you not only at your ease but at your best when talking to him which is given to few men of note." (101) Asquith later commented that "Margot... took possession of me... The passion which comes, I suppose, to everyone once in life, visited and conquered me." (97)

In the summer of 1891 the Asquiths had a holiday on the Isle of Arran. On 20th August, their son, Herbert Asquith, became feverish and Helen Asquith moved in to his room to nurse him. The following day Helen was taken ill. A doctor was called and he diagnosed typhoid and she died on 11th September. Herbert Henry Asquith wrote that night: "She died at nine this morning. So end twenty years of love and fourteen of unclouded union. I was not worthy of it, and God has taken her. Pray for me." (98)

In the 1892 General Election held in July, Gladstone's Liberal Party won the most seats (272) but he did not have an overall majority and the opposition was divided into three groups: Conservatives (268), Irish Nationalists (85) and Liberal Unionists (77). Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, refused to resign on hearing the election results and waited to be defeated in a vote of no confidence on 11th August. Gladstone, now 84 years old, formed a minority government dependent on Irish Nationalist support. (99)

Asquith was appointed as Gladstone's Home Secretary. On hearing the news he wrote to Margot Tennant. "Here I am, full from my earliest days of political ambition, still young, and just admitted to one of the best places in the Cabinet, and yet I undertake to say that there is hardly a man in London more profoundly depressed than I am today. You know why... What use to me... are honours, power, a career, if I am to be cut off from the hope and promise of all that is purest and highest in my life?" (100)

The reason for this depression was that Margot had rejected his proposal of marriage. Asquith was twelve years older than Margot and she was in love with another man. However, she eventually changed her mind and they were married on 10th May 1894. Margot wrote in her diary five days after her marriage to Asquith: "I realized that in some ways with all his tact and delicacy, all his intellect and bigness, all his attributes, he had a common place side to him which nothing could alter... It is not in his nature to feel the subtlety of love making, the dazzle and fun of it, the tiny almost untouchable fellowship of it... He has passion, devotion, self-mastery, but not the nameless something that charms and compels and receives and combats a woman's most fastidious advances." (101)

Margot later confessed that she had been wrong to doubt the wisdom of marrying Asquith: "I can truly say no words of mine today can at all, describe how differently things have turned out for me!!!! My in-loveness (for 9 years) with Peter Flower - my love for Evan Charteris, my hundred and one loves and friendships are like so much waste paper! My criticisms of Henry are pathetically stupid, narrow and crass. The fact is I was... a sort of drunkard of all social caresses up to the moment of marriage." (102)

Over the next few years Margot had five children but only Elizabeth Asquith (1897–1945) and Anthony Asquith (1902–1968) survived as three of them died at birth. Margot had a reputation for speaking her mind and relations with her step-children were difficult. This was especially true of her dealings with Raymond Asquith, the eldest, and Violet Bonham Carter, the only daughter.

William Gladstone and John Morley concentrated on Irish Home Rule, whereas Henry Asquith and his under-secretary, Herbert Gladstone, the prime minister's son, were put in charge of important aspects of the Liberals' programme of domestic reform. Asquith's position was difficult, for the Liberals in the Commons had only 272 MPs to the combined Unionist vote of 314, and thus relied on the Irish home-rulers for their majority. "It soon became clear that the Unionists intended to use their own majority in the Lords not merely to stop home rule but to spoil whatever items of the Liberals' legislative programme they disliked". (103)

The Irish Home Rule Bill was introduced on 13th February 1893. William Gladstone personally took the bill through the "committee stage in a remarkable feat of physical and mental endurance". After eighty-two days of debate it was passed in the House of Commons on 1st September by 43 votes (347 to 304). Gladstone wrote in his diary, "This is a great step. Thanks be to God." (104)

On 8th September, 1893, after four short days of debate, the House of Lords rejected the bill, by a vote of 419 to 41. "It was a division without precedent, both for the size of the majority and the strength of the vote. There were only 560 entitled to vote, and 82 per cent of them did did so, even though there was no incentive of uncertainty to bring remote peers to London." (105)

Gladstone considered resigning and calling a new general election on the issue. However, he suspected that he could not mount a successful electoral indictment of the House of Lords on Irish Home Rule. He therefore pushed ahead with the Workmen's Compensation Act, a measure that was extremely unpopular with employers. Asquith was given responsibility for taking the bill through Parliament. The act dealt with the right of workers for compensation for personal injury. It replaced the Employer's Liability Act 1880, which required the injured worker the right to sue the employer and put the burden of proof on the employee. (106)

In the autumn of 1893 Asquith prepared a Welsh Disestablishment and Disendowment Bill. In Parliament the measure was opposed by Conservative Party, who hated the slightest interference with the privileges of the established church. It was also attacked by the radical wing of the Liberal Party, who felt that the legislation did not go far enough. The leader of this group was David Lloyd George, who wanted the church stripped of the bulk of its wealth. Asquith complained to the Chief Whip, Tom Ellis, that he was far too lenient with Lloyd George's "underhand and disloyal" tactics. (107)

In December 1893, Gladstone came into conflict with his own party over the issue of defence spending. The Conservative Party began arguing for an expansion of the Royal Navy. Gladstone made it clear that he was opposed to this policy. William Harcourt, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was willing to increase naval expenditure by £3 million. John Poyntz Spencer, the First Lord of the Admiralty, agreed with Harcourt. Gladstone refused to budge on the issue and wrote that he would not "break to pieces the continuous action of my political life, nor trample on the tradition received from every colleague who has ever been my teacher" by supporting naval rearmament. (108)

Conservatives continued to block the government's legislation. After accepting the Lords' amendments to the Local Government Bill "under protest" he decided to resign. In his last speech to the House of Commons on 1st March, 1894, he suggested that the time had come to change the rules of the British Parliament so that the House of Lords would no longer have the power to refuse to pass Bills which had been passed by the House of Commons. (109)

Archibald Primrose, Lord Rosebery, became the new prime minister. His period in power was only short as the Liberal Party was defeated in the 1895 General Election. Rosebery resigned the leadership of the Liberal Party in October 1896. Asquith was seen by many as his natural successor but he rejected the offer as he did not have a private income and could not afford to give up his income from his work as a lawyer. (110)

The job went instead to Henry Campbell-Bannerman. Asquith was convinced that he would eventually replace Campbell-Bannerman, as he was sixty-two years old and fifteen years his senior. He expected his financial situation to improve and in a couple of years time he would be ready to take over the leadership. As Margot Asquith pointed out: "Campbell-Bannerman is not young or very strong and is not likely to prove a formidable long-term rival." (111)

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, the second child and the elder son of William George and Elizabeth Lloyd, was born in Chorlton-on-Medlock, on 17th January, 1863. His father was the son of a farmer who had a desire to become a doctor or a lawyer. However, unable to afford the training, he became a teacher. He wrote in his diary, "I cannot make up my mind to be a school master for life... I want to occupy higher ground somehow or other." (112)

William George married Elizabeth Lloyd, the daughter of a shoemaker, on 16th November 1859. He became a school teacher in Newchurch in Lancashire, but in 1863, he bought the lease of Bwlford, a smallholding of thirty acres near Haverfordwest. However, he died, from pneumonia aged forty-four, on 7th June, 1864. (113)

Elizabeth Lloyd, was only 36 years-old and as well as having two young children, Mary Ellen and David, she was also pregnant with a third child. Elizabeth sent a telegram to her unmarried brother, Richard Lloyd, who was a master-craftsman with a shoe workshop in Llanystumdwy, Caernarvonshire. He arranged for the family to live with him. According to Hugh Purcell: "Richard Lloyd... was an autodidact whose light burned long into the night as he sought self-improvement. He ran the local debating society and regarded politics as a public service to improve people's lives." (114)

The Lloyd family were staunch Nonconformists and worshipped at the Disciples of Christ Chapel in Criccieth. Richard Lloyd was Welsh-speaking and deeply resented English dominance over Wales. Richard was impressed by David's intelligence and encouraged him in everything he did. David's younger brother, William George, later recalled: "He (David) was the apple of Uncle Lloyd's eye, the king of the castle and, like the other king, could do no wrong... Whether this unrestrained admiration was wholly good for the lad upon whom it was lavished, and indeed for the man who evolved out of him, is a matter upon which opinions may differ." (115)

David Lloyd George acknowledged the help given to him by Richard Lloyd: "All that is best in life's struggle I owe to him first... I should not have succeeded even so far as I have were it not for the devotion and shrewdness with which he has without a day's flagging kept me up to the mark... How many times have I done things... entirely because I saw from his letters that he expected me to do them." (116)

Lloyd George was an intelligent boy and did very well at his local school. Lloyd George's headmaster, David Evans, was described as a "teacher superlative quality". His "outstanding gift was for holding the attention of the young and for arousing their enthusiasm". Lloyd George said that "no pupil ever had a finer teacher". Evans returned the compliment: "no teacher ever had a more apt pupil". (117)

In 1877 David Lloyd George decided he wanted to be a lawyer. After passing his Law Preliminary Examination he found a post at a firm of solicitors in Portmadog. He started work soon after his sixteenth birthday. He passed his final law examination in 1884 with a third-class honours and established his own law practice in Criccieth. He soon developed a reputation as a solicitor who was willing to defend people against those in authority. (118)

Lloyd George began getting involved in politics. His uncle was a member of the Liberal Party with a strong hatred of the Conservative Party. At the age of 18 he visited the House of Commons and noted in his diary: "I will not say that I eyed the assembly in a spirit similar to that in which William the Conqueror eyed England on his visit to Edward the Confessor, as the region of his future domain." (119)

In 1888 Lloyd George married Margaret Owen, the daughter of a prosperous farmer. He developed a "deserved reputation for promiscuity". One of his biographers has pointed out: "Not for nothing was his nickname the Goat. He had a high sex drive without the furtiveness that often goes with it. Although he knew that the fast life, as he called it, could ruin his career he took extraordinary risks. Only two years after his marriage he had an affair with an attractive widow of Caernavon, Mrs Jones... She gave birth to a son who grew up to look remarkably like Richard, Lloyd George's legitimate son who was born the previous year." (120)

Lloyd George joined the local Liberal Party and became an alderman on the Caernarvon County Council. He also took part in several political campaigns including one that attempted to bring an end to church tithes. Lloyd George was also a strong supporter of land reform. As a young man he had read books by Thomas Spence, John Stuart Mill and Henry George on the need to tackle this issue. He had also been impressed by pamphlets written by George Bernard Shaw and Sidney Webb of the Fabian Society on the need to tackle the issue of land ownership.

In 1890 Lloyd George was selected as the Liberal candidate for the Caernarvon Borough constituency. A by-election took place later that year when the sitting Conservative MP died. Lloyd George fought the election on a programme which called for religious equality in Wales, land reform, the local veto in granting licenses for the sale of alcohol, graduated taxation and free trade. Lloyd George won the seat by 18 votes and at twenty-seven became the youngest member of the House of Commons. (121)

The Boer War

The Boers (Dutch settlers in South Africa), under the leadership of Paul Kruger, resented the colonial policy of Joseph Chamberlain and Alfred Milner which they feared would deprive the Transvaal of its independence. After receiving military equipment from Germany, the Boers had a series of successes on the borders of Cape Colony and Natal between October 1899 and January 1900. Although the Boers only had 88,000 soldiers, led by the outstanding soldiers such as Louis Botha, and Jan Smuts, the Boers were able to successfully besiege the British garrisons at Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley. On the outbreak of the Boer War, the conservative government announced a national emergency and sent in extra troops. (122)

Asquith called for support for the government and "an unbroken front" and became known as a "Liberal Imperialist". Campbell-Bannerman disagreed with Asquith and refused to endorse the dispatch of ten thousand troops to South Africa as he thought the move "dangerous when the the government did not know what it might lead to". David Lloyd George also disagreed with Asquith and complained that this was a war that had been started by Joseph Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary. (123)

It has been claimed that Lloyd George "sympathised with the Boers, seeing them as a pastoral community like Welshmen before the industrial revolution". He supported their claim for independence under his slogan "Home Rule All Round" assuming "it would lead to a free association within the British Empire". He argued that the Boers "would only be subdued after much suffering, cruelty and cost." (124)

Lloyd George also saw this anti-war campaign as an opportunity to stop Asquith becoming the next leader of the Liberals. Lloyd George was on the left of the party and had been campaigning with little success for the introduction of old age pensions. The idea had been rejected by the Conservative government as being "too expensive". In one speech he made the point: "The war, I am told, has already cost £16,000,000 and I ask you to compare that sum with what it would cost to fund the old age pension schemes.... when a shell exploded it carried away an old age pension and the only satisfaction was that it killed 200 Boers - fathers of families, sons of mothers. Are you satisfied to give up your old age pension for that?" (125)

The overwhelmingly majority of the public remained fervently jingoistic. David Lloyd George came under increasing attack and after a speech at Bangor on 4th April 1900, he was interrupted throughout his speech, and after the meeting, as he was walking away, he was struck over the head with a bludgeon. His hat took the impact and although stunned, he was able to take refuge in a cafe, guarded by the police.

On 5th July, 1900, at a meeting addressed by Lloyd George in Liskeard ended in pandemonium. Around fifty "young roughs stormed the platform and occupied part of it, while a soldier in khaki was carried shoulder-high from end to end of the hall and ladies in the front seats escaped hurriedly by way of the platform door." Lloyd George tried to keep speaking and it was only when some members of the audience began throwing chairs at him that he left the hall. (126)

On 25th July, a motion on the Boer War, caused a three way split in the Liberal Party. A total of 40 "Liberal Imperialists" that included H. H. Asquith, Edward Grey, Richard Haldane, and Archibald Primrose, Lord Rosebery, supported the government's policy in South Africa. Henry Campbell-Bannerman and 34 others abstained, whereas 31 Liberals, led by Lloyd George voted against the motion.

Robert Cecil, the Marquess of Salisbury, decided to take advantage of the divided Liberal Party and on 25th September 1900, he dissolved Parliament and called a general election. Lloyd George, admitted in one speech he was in a minority but it was his duty as a member of the House of Commons to give his constituents honest advice. He went on to make an attack on Tory jingoism. "The man who tries to make the flag an object of a single party is a greater traitor to that flag than the man who fires upon it." (127)

Henry Campbell-Bannerman with a difficult task of holding together the strongly divided Liberal Party and they were unsurprisingly defeated in the 1900 General Election. The Conservative Party won 402 seats against the 183 achieved by Liberal Party. However, anti-war MPs did better than those who defended the war. David Lloyd George increased the size of his majority in Caernarvon Borough. Other anti-war MPs such as Henry Labouchere and John Burns both increased their majorities. In Wales, of ten Liberal candidates hostile to the war, nine were returned, while in Scotland every major critic was victorious.

John Grigg argues that it was not the anti-war Liberals who lost the party the election. "The Liberals were beaten because they were disunited and hopelessly disorganised. The war certainly added to their confusion, but this was already so flagrant that they were virtually bound to lose, war or no war. The government also had the advantage of improved trade since 1895, which the war, admittedly, turned into a boom. All things considered, the Liberals did remarkably well." (128)

Emily Hobhouse, formed the Relief Fund for South African Women and Children in 1900. It was an organisation set up: "To feed, clothe, harbour and save women and children - Boer, English and other - who were left destitute and ragged as a result of the destruction of property, the eviction of families or other incidents resulting from the military operations". Except for members of the Society of Friends, very few people were willing to contribute to this fund. (129)

Hobhouse arrived in South Africa on 27th December, 1900. Hobhouse argued that Lord Kitchener’s "Scorched Earth" policy included the systematic destruction of crops and slaughtering of livestock, the burning down of homesteads and farms, and the poisoning of wells and salting of fields - to prevent the Boers from re-supplying from a home base. Civilians were then forcibly moved into the concentration camps. Although this tactic had been used by Spain (Ten Years' War) and the United States (Philippine-American War), it was the first time that a whole nation had been systematically targeted. She pointed this out in a report that she sent to the government led by Robert Cecil, the Marquess of Salisbury. (130)

When she returned to England, Hobhouse campaigned against the British Army's scorched earth and concentration camp policy. William St John Fremantle Brodrick, the Secretary of State for War argued that the interned Boers were "contented and comfortable" and stated that everything possible was being done to ensure satisfactory conditions in the camps. David Lloyd George took up the case in the House of Commons and accused the government of "a policy of extermination" directed against the Boer population. (131)

After meeting Hobhouse, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, gave his support to Lloyd George against Asquith and the Liberal Imperialists on the subject of the Boer War. In a speech to the National Reform Union he provided a detailed account of Hobhouse's report. He asked "When is a war not a war?" and then provided his own answer "When it is carried on by methods of barbarism in South Africa". (132)

The British action in South Africa grew increasingly unpopular and anti-war Liberal MPs and the leaders of the Labour Party saw it as an example of the worst excesses of imperialism. The Boer War ended with the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging in May 1902. The peace settlement brought to an end the Transvaal and the Orange Free State as Boer republics. However, the British granted the Boers £3 million for restocking and repairing farm lands and promised eventual self-government. David Lloyd George commented: "They are generous terms for the Boers. Much better than those we offered them 15 months ago - after spending £50,000 in the meantime". (133)

1902 Education Act

On 24th March 1902, Arthur Balfour presented to the House of Commons an Education Bill that attempted to overturn the 1870 Education Act that had been brought in by William Gladstone. It had been popular with radicals as they were elected by ratepayers in each district. This enabled nonconformists and socialists to obtain control over local schools.

The new legislation abolished all 2,568 school boards and handed over their duties to local borough or county councils. These new Local Education Authorities (LEAs) were given powers to establish new secondary and technical schools as well as developing the existing system of elementary schools. At the time more than half the elementary pupils in England and Wales. For the first time, as a result of this legislation, church schools were to receive public funds. (134)

Nonconformists and supporters of the Liberal and Labour parties campaigned against the proposed act. David Lloyd George led the campaign in the House of Commons as he resented the idea that Nonconformists contributing to the upkeep of Anglican schools. It was also argued that school boards had introduced more progressive methods of education. "The school boards are to be destroyed because they stand for enlightenment and progress." (135)

In July, 1902, a by-election at Leeds demonstrated what the education controversy was doing to party fortunes, when a Conservative Party majority of over 2,500 was turned into a Liberal majority of over 750. The following month a Baptist came near to capturing Sevenoaks from the Tories and in November, 1902, Orkney and Shetland fell to the Liberals. That month also saw a huge anti-Bill rally held in London, at Alexandra Palace. (136)

Despite the opposition the Education Act was passed in December, 1902. John Clifford, the leader of the Baptist World Alliance, wrote several pamphlets about the legislation that had a readership that ran into hundreds of thousands. Balfour accused him of being a victim of his own rhetoric: "Distortion and exaggeration are of its very essence. If he has to speak of our pending differences, acute no doubt, but not unprecedented, he must needs compare them to the great Civil War. If he has to describe a deputation of Nonconformist ministers presenting their case to the leader of the House of Commons, nothing less will serve him as a parallel than Luther's appearance before the Diet of Worms." (137)

Clifford formed the National Passive Resistance Committee and over the next four years 170 men went to prison for refusing to pay their school taxes. This included 60 Primitive Methodists, 48 Baptists, 40 Congregationalists and 15 Wesleyan Methodists. The father of Kingsley Martin, was one of those who refused to pay: "Each year father and the other resisters all over the country refused to pay their rates for the upkeep of Church Schools. The passive resistors thought the issue of principle paramount and annually surrendered their goods instead of paying their rates. I well remember how each year one or two of our chairs and a silver teapot and jug were put out on the hall table for the local officers to take away. They were auctioned in the Market Place and brought back to us." (138)

David Lloyd George made clear that this was a terrible way to try and change people's opinions: "There is no greater tactical mistake possible than to prosecute an agitation against an injustice in such a way as to alienate a large number of men who, whilst they resent that injustice as keenly as anyone, either from tradition or timidity to be associated with anything savouring of revolutionary action. Such action should always be the last desperate resort of reformers... The interests of a whole generation of children will be sacrificed. It is not too big a price to pay for freedom, if this is the only resource available to us. But is it? I think not. My advice is, let us capture the enemy's artillery and turn his guns against him." (139)

Free Trade

Arthur Balfour became prime minister in June 1902. With the Liberal Party divided over the issue of the British Empire, it appeared that their chances of regaining office in the foreseeable future seemed remote. Then on 15th May 1903, Joseph Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary, exploded a political bombshell with a speech in Birmingham advocating a system of preferential colonial tariffs. Asquith was convinced that Chamberlain had made a serious political mistake and after reading a report of the speech in The Times he told his wife: "Wonderful news today and it is only a question of time when we shall sweep the country". (140)

Asquith saw his opportunity and pointed out in speech after speech that a system of "preferential colonial tariffs" would mean taxes on food imported from outside the British Empire. Colin Clifford has pointed out: "Chamberlain had picked the one issue guaranteed to split the Unionist and unite the Liberals in the defence of Free Trade. The topic was tailor-made for Asquith and the next few months he shadowed Chamberlain's every speech, systematically tearing his argument to shreds. The Liberals were on the march again." (141)

As well as uniting the Liberal Party it created a split in the Conservative Party as several members of the cabinet believed strongly in Free Trade, including Charles T. Richie, the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Leo Amery argued: "The Birmingham speech was a challenge to free trade as direct and provocative as the theses which Luther nailed to the church door at Wittenberg." (142)

Arthur Balfour now began to have second thoughts on this policy and warned Joseph Chamberlain about the impact on the electorate in the next general election: "The prejudice against a small tax on food is not the fad of a few imperfectly informed theorists, it is a deep rooted prejudice affecting a large mass of voters, especially the poorest class, which it will be a matter of extreme difficulty to overcome." (143)

Asquith made speeches that attempted to frighten the growing working-class electorate "to whom cheap food had been a much cherished boon for the last quarter of a century and it annoyed the middle class who saw the prospect of a reduction in the purchasing power of their fixed incomes." As well as splitting the Conservative Party it united "the Liberals who had been hitherto hopelessly divided on all the main political issues." (144)

Arthur Balfour resigned on 4th December 1905. Henry Campbell-Bannerman refused to form a minority government and insisted on an immediate dissolution of Parliament. It has been claimed that the Liberal Party "was on the crest of a wave and it was clear that the man who had put them there was not their leader, Campbell-Bannerman, but his deputy, Asquith." (145)