Thomas Hughes

Thomas Hughes, the second of the six sons of John Hughes (1790–1857), author, and his second wife, Margaret Elizabeth Wilkinson (1797–1887), was born in Uffington, Berkshire, on 20th October, 1822. Jane Elizabeth Senior (1828–1877) was his only sister. (1)

Thomas spent almost all his years up to early manhood in the closest companionship with this elder brother, George Edward (1821–1872). They went together in the autumn of 1830 to a private school at Twyford, near Winchester, where they had met Charles Blachford Mansfield. In February 1834 the two brothers were sent to Rugby, Tom being then eleven years old. (2)

Thomas Hughes was captain of the cricket team, but did not excel academically. He later said that the "most marked characteristic" of his generation of Rugby boys was "the feeling that in school and close we were in training for a big fight - were in fact already engaged in it - a fight which would last all our lives, and try all our powers, physical, intellectual, and moral, to the utmost." (3)

Hughes went to Oriel College, Oxford, in February 1842. He enjoyed playing sports but did not try to work for an honours degree. His tutors were Arthur Hugh Clough (1819–1861) , whose fag he had been at Rugby, and James Fraser (1818–1885), later an ally in the co-operative movement. Clough was a major influence on Hughes. A close friend of John Ruskin and Thomas Carlyle, he shared their radical political beliefs. Clough called himself a republican, disliked class distinction and was highly critical of the capitalist system. (4)

Thomas Hughes - Christian Socialist

According to Brenda Colloms: "Hughes was disturbed by the wretched living conditions of the shopworkers whose homes he passed each morning as he walked to his chambers in Lincoln's Inn. He felt outraged when he watched the urchins playing in the street whilst the gardens of Lincoln's Inn were green and inviting, and one afternoon he used his tenant's key to open the gate and invite the children inside. He was visited by the beadle of the Inn who threatened, white with fury, to take away his key if he ever repeated the experiment. That incident with the children gave an indication of Hughes's real interests. He was ready to work solidly at the law for a living but his heart lay in his social work." (5)

In August 1843, Hughes became engaged to his sister's friend Anne Frances Ford (c.1826–1910), daughter of the Revd Dr James Ford, prebendary of Exeter. Meanwhile Hughes had come down from Oxford, taken rooms in Lincoln's Inn, and begun to read for the bar. After some opposition they were married on 17 August 1847. According to his biographer, Charlotte Mitchell: "The period between his engagement and his marriage was a crucial one, which saw the political conversion which shaped the rest of his life. While still at Oxford he had travelled, in the long vacation of 1844, to Scotland and the north, and become convinced of the need to repeal the corn laws". He also began to attend the lectures of Frederick Denison Maurice, who encouraged young students to discuss social questions and to work among the poor. (6)

On 10th April, 1848, a group of Christians who supported Chartism held a meeting in London. People who attended the meeting included Frederick Denison Maurice, Charles Kingsley, John Ludlow and Thomas Hughes. The meeting was a response to the decision by the House of Commons to reject the recent Chartist Petition. The men, who became known as Christian Socialists, discussed how the Church could help to prevent revolution by tackling what they considered were the reasonable grievances of the working class. (7)

Feargus O'Connor had been vicious attacks on other Chartist leaders such as William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, Bronterre O'Brien and Henry Vincent who advocated Moral Force. O'Connor questioned this strategy and began to make speeches where he spoke of being willing "to die for the cause" and promising to "lead people to death or glory". O'Connor became the leader of what became known as the Physical Force Chartists, Disturbed by these events members of the Christian Socialist movement volunteered to become special constables at these demonstrations. (8) John Ludlow later wrote: "The present generation has no idea of the terrorism which was at that time exercised by the Chartists." (9)

Frederick Denison Maurice was acknowledged as the leader of the group and his book The Kingdom of Christ (1838) became the theological basis of Christian Socialism. In the book Maurice argued that politics and religion are inseparable and that the church should be involved in addressing social questions. Maurice rejected individualism, with its competition and selfishness, and suggested a socialist alternative to the economic principles of laissez faire. He suggested profit sharing as a way of improving the status of the working classes and as a means of producing a just, Christian society. (10)

Thomas Hughes was a passionate Christian Socialist and later wrote: "I certainly thought (and for that matter have not altered my opinion to this day) that here we had found the solution to the great labour question: but I was also convinced that we had nothing to do but just announce it and found an association or two, in order to convert all England, and usher in the millennium at once so plain did the whole thing seem to me." (11)

Christian Socialist Journals

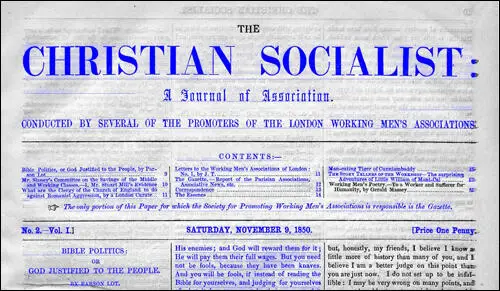

In May 1848, Thomas Hughes, Charles Kingsley, Frederick Denison Maurice, and John Ludlow decided to publish a penny journal, Politics for the People, and this was considered the starting-point of the Christian Socialist movement. It was "sympathetic to the poor and based upon the acknowledgment that God rules in human society... They addressed themselves to workmen. They confessed that they were not workmen, but asked for workmen's help in bridging the gulf that divided them". (12)

Politics for the People was an expensive journal to produce and by July 1848, after seventeen editions, the decision was taken to stop publication. Hughes now concentrated on the new journal, Christian Socialist, which appeared from 2nd November, 1850 to 28th June 1851. It promoted the Christian view of a socialist society. Ludlow, the first editor began to diffuse the principles of co-operation by the practical application of Christianity to the purposes of trade and industry. (13) Hughes later replaced Ludlow as editor of the journal. (14)

The Christian Socialist covered every topic imaginable within the field of national and ecclesiastical politics and preached the message of national and ecclesiastical politics and preached the message of socialism through articles by all the major member of the group. (15)

In an editorial in the edition published on 2nd November 1850, the journal attempted to explain its philosophy: "A new idea has gone abroad into the world. That is Socialism, the latest-born of the forces now at work in modern society, and Christianity, the eldest born of those forces, are in their nature not hostile, but akin to each other, or rather that the one is but the development, the outgrowth, the manifestation of the other, so that even the strangest and most monstrous forms of Socialism are at bottom but Christian heresies. That Christianity, however feeble and torpid it may seem to many just now, is truly but as an eagle at moult, shedding its worn-out plumage; that Socialism is but the livery of the nineteenth century (as Protestantism was its livery of the sixteenth) which is now putting on, to spread long its mighty wings for a broader and heavenlier flight. That Socialism without Christianity, on the one hand, is as lifeless as the feathers without the bird, however skilfully the stuffer may dress them up into an artificial semblance of life; and that therefore every socialist system which has endeavoured to stand alone has hitherto in practice either blown up or dissolved away; whilst almost every socialist system which has maintained itself for anytime has endeavoured to stand, or unconsciously to itself has stood, upon those moral grounds of righteous, self-sacrifice, mutual affection, common brotherhood, which Christianity vindicates to itself for an everlasting heritage." (16)

Some members of the Christian Socialist movement, including Thomas Hughes, John Ludlow, Edward Vansittart Neale and Charles Kingsley, supported the growth of trade unionism. In 1852, George Frederick Robinson, published a plea for democracy entitled The Duty of the Age which he submitted to Hughes, Kingsley, and Ludlow, members of the Christian Socialist Publication Committee, and they passed the manuscript for press. When, however, Frederick Denison Maurice, chairman of the committee, read the tract after an edition was printed off, he condemned its extreme radical tendency and gave orders, which were carried out, for the suppression of the pamphlet. (17)

This was the first ideological split between Hughes and Maurice who did not support universal suffrage. Maurice suspected that any fully democratic system would lead to either "a most accursed sacerdotal rule or a military despotism". Maurice did not consider the working-class to be intelligent enough to become electors whereas Hughes believed in universal suffrage for all adult males. (18)

Christian Socialists began offering lectures in 1853 for working men and women in Castle Street East (by Oxford Street) and helping to form eight Working Men's Associations. The night school eventually became the Working Men's College. Thomas Hughes taught some law and Bible classes at various times, but his real success was in teaching boxing. He succeeded as its principal after Maurice's death and served from 1872 to 1883. (19)

Tom Brown's Schooldays

In April 1856 Hughes published Tom Brown's Schooldays. It has been argued by Ian Ousby that: "The first great school story, Tom Brown's Schooldays set a pattern for future writing in the genre. Written when its author was still young enough to remember his own days at Rugby, the novel describes the experiences of an upper middle-class boy going to boarding school for the first time. Shy at first, he learns how to put up with teasing from the older boys while carrying out various menial duties as their 'fag'. His two best friends represent opposite poles in behaviour and attitude, with Arthur gentle, law-abiding and idealistic and East mischievous and irrelevant. But when some younger boys are picked on by the notorious school bully Flashman, it is East and Tom who bravely stand up to him, despite their small size." (20)

His biographer, John Llewelyn Davies, claims that: "His object in writing it was to do good. He had had no literary ambition, and no friend of his had ever thought of him as an author. Tom Brown's School Days is a piece of life, simply and modestly presented, with a rare humour playing all over it, and penetrated by the best sort of English religious feeling. And the life was that which is peculiarly delightful to the whole English-speaking race that of rural sport and the public school. The picture was none the less welcome, and is none the less interesting now, because there was a good deal that was beginning to pass away in the life that it depicts. The book was written expressly for boys, and it would be difficult to measure the good influence which it has exerted upon innumerable boys by its power to enter into their ways and prejudices, and to appeal to their better instincts; but it has commended itself to readers of all ages, classes, and characters." (21)

It has been suggested that Tom Brown is based on Thomas Hughes and his own time at Rugby School. However, the classical scholar John Conington (1825–1869), who was at school with Hughes, cruelly recalled him as "on the whole very like Tom Brown, only not so intellectual." Its success was rapid, five editions being issued in nine months. It sold sold 28,000 copies by the end of 1862 and gone through fifty-three editions by 1892. Nor did the fact of its being about an English public school prevent it from circulating widely in America and Europe. (22)

Co-operative Stores

Edward Vansittart Neale was another important figure in the Christian Socialist movement. Matthew Lee has suggested: "Neale was central in shifting the focus of the movement from promotion of self-governing workshops to co-operation on a larger scale. He funded and founded the first London co-operative stores in Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square, and advanced capital for two unsuccessful builders' associations. Initially ignorant of northern co-operation on the Rochdale and redemptionist models, Neale became a swift convert to consumers' co-operation and became allied with many former Owenites." (23)

Co-operative associations did not benefit under the law from many of the usual benefits of trade. Thus they could not enforce contracts or secure themselves against fraudulent or negligent officials. In 1850 Hughes approached an MP by the name of Robert Aglionby Slaney, whose Select Committee of the House of Commons was to report on "Investments for the Savings of the Middle and Working Classes". In June 1852 the recommendations of the Act, Committee were taken up in the Industrial and Provident Societies which gave real advantages to the associations. They were denied the privilege of limited liability, but they were freed from from much of the legislation regarding friendly societies. (24)

Thomas Hughes fully supported Neale's belief in the importance of establishing cooperative stores. This brought him into conflict with other Christian Socialists like John Ludlow because he challenged the assumption that all associations had to be producer co-operatives rather than consumer ones. Ludlow was furious seeing it as a betrayal of the fundamental principles of the Society. Ludlow presented an ultimatum at the Promoters' Council meeting, that either Neale and Hughes went or he did. However, Frederick Denison Maurice, managed to persuade Ludlow to withdraw the threat. (25)

In 1865 Hughes came into conflict with some Christian Socialists over the case of John Edward Eyre, the British Governor of Jamaica. Eyre had suppressed the Morant Bay Rebellion. Up to 439 black people were killed in the reprisals, some 600 flogged, and about 1000 houses burnt down. Hughes and John Ludlow. helped form the Jamaica Committee in criticism of Eyre's excessive violence, while Charles Kingsley, Thomas Carlyle and John Ruskin defended the actions of Eyre. Ludlow saw Kingsley's views as tantamount to a vicious racism and resolved to sever connections with him. (26)

Liberal Party MP

Thomas Hughes was selected by the Liberal Party to stand for the seat of Lambeth in the 1865 General Election. He was elected and soon established himself as one of the most progressive members of the House of Commons. When the head of the Conservative government, Earl of Derby decided to set up a Royal Commission on Trade Unions in 1867, Hughes was one of its members. George Potter, writing for the Bee-Hive, called for a working man to be included or a "gentleman well known to the working classes as possessing a practical knowledge of the working of Trade Unions, and in whom they might feel confidence." The government rejected the idea of a working man but they did ask Frederic Harrison to serve on the commission. Harrison was a very useful member of the commission, preparing union witnesses by telling them in advance what questions would be asked and rescued the from difficult situations during their cross-examination. (27)

Robert Applegarth, the general secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners was chosen as a union observer of the proceedings. Applegarth worked hard checking the various accusations of the employers and providing information to the two pro-union members of the Royal Commission, Hughes and Harrison. Applegarth also appeared as a witness and it was generally accepted that he was the most impressive of all the trade unionists who gave evidence before the commission. (28)

Thomas Hughes, Frederic Harrison, and Thomas Anson, 2nd Earl of Lichfield refused to sign the Majority Report that was hostile to trade unions and instead produced a Minority Report where he argued that trade unions should be given privileged legal status. Harrison suggested several changes to the law: (i) Persons combining should not be liable for indictment for conspiracy unless their actions would be criminal if committed by a single person; (ii) The common law doctrine of restraint of trade in its application to trade associations should be repealed; (iii) That all legislation dealing with specifically with the activities of employers or workmen should be repealed; (iv) That all trade unions should receive full and positive protection for their funds and other property. (29)

In 1868 he was glad to exchange this unwieldy and unmanageable constituency for the borough of Frome, for which he was returned at the general election. John Llewelyn Davies argues that "In the House of Commons the line he took was definitely that of a reformer, and especially of a friend of the working classes; a trades union bill he introduced was read a second time on 7 July 1869, but made no further progress. He was not a very successful speaker, and, though greatly liked and respected, he would not have been able to reach the front rank in politics." (30)

Thomas Hughes was appointed principal of the Working Men's College in 1872. In 1880 he became involved in a project to found a co-operative settlement in Tennessee to be populated by English public schoolboys who found no opportunities at home. One of those who took part was his younger brother William Hastings Hughes (1834–1907). By 1882 it was evident that the project had failed, though it struggled on for a few years. Some of the buildings at Rugby, Tennessee, still exist, but as a co-operative enterprise it was given up in 1891. (31)

Thomas Hughes died of congestion of the lungs at the Royal Crescent Hotel, 101 Marine Parade, Brighton, on his way to Europe for his health, on 22nd March 1896. He was buried in Woodvale Cemetery, Brighton, on 25th March 1896.

Primary Sources

(1) Brenda Colloms, Victorian Visionaries (1982)

Like Ludlow before him, he was disturbed by the wretched living conditions of the shopworkers whose homes he passed each morning as he walked to his chambers in Lincoln's Inn. He felt outraged when he watched the urchins playing in the street whilst the gardens of Lincoln's Inn were green and inviting, and one afternoon he used his tenant's key to open the gate and invite the children inside. He was visited by the beadle of the Inn who threatened, white with fury, to take away his key if he ever repeated the experiment. That incident with the children gave an indication of Hughes's real interests. He was ready to work solidly at the law for a living but his heart lay in his social work.

(2) Thomas Hughes, quoted in Brenda Colloms, Victorian Visionaries (1982)

I certainly thought (and for that matter have not altered my opinion to this day) that here we had found the solution to the great labour question: but I was also convinced that we had nothing to do but just announce it and found an association or two, in order to convert all England, and usher in the millennium at once so plain did the whole thing seem to me.

(3) John Llewelyn Davies, Thomas Hughes: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (1901)

It was through his residence in Lincoln's Inn that he came under the great influence of his life. F. D. Maurice was then chaplain of the Inn, and, whilst his personal character won the reverence of the young student, his teaching came home to his needs and aspirations and deepest convictions, and completely mastered him. Maurice had no more devoted disciple than Tom Hughes. It was the work of his life to put in practice what he learnt from Maurice. In the latter part of 1848 he offered himself as a fellow-worker to the little band of Christian socialists who had gathered round Maurice, in which Mr. John M. Ludlow, for many years Hughes's closest friend and ally, and Charles Kingsley, and his old school-fellow Charles Mansfield, were already enrolled. The practical part of Christian socialism was the co-operative movement, especially in its 'productive' form. This branch of it has been overshadowed by the vast store system; but it was co-operative production that had the sympathy and advocacy of Hughes and the more enthusiastic promoters of co-operation. In his later years Hughes was accustomed to denounce with some vehemence what he regarded as a desertion of the true co-operative principle by those who cared only for the stores, and who gave no share in the business to the employees of the store and the factory. The early businesses set up by the Christian socialists did not prosper, but Hughes never despaired of the cause. He was one of the most diligent and ardent of its promoters, attending conferences, giving legal advice, and going on missionary tours. He contributed to the 'Christian Socialist' and the 'Tracts on Christian Socialism,' and acted for some months as editor of the 'Journal of Association.' By giving evidence in 1850 before the House of Commons committee on the savings of the middle and working classes, and by other persevering efforts, he aided the passing of the Industrial and Provident Societies Act in 1893.