Robert Bernays

Robert Bernays, the fourth child and third son of Stewart Frederic Lewis Bernays, rector of Great Stanmore, and his wife, Lillian Stephenson, was born on 6th May 1902. His great-uncle was chief rabbi in Hamburg. He was educated privately at Rossall School (1915-1920) and went up to Worcester College, as an exhibitioner in history in 1922, being awarded an aegrotat degree in 1925. A member of the Liberal Party, he was president of the Oxford Union. (1)

Bernays became a journalist and later leader writer with the Daily News. In September 1927 he was selected as the Liberal candidate to fight Rugby. The Rugby Liberal Association stated he was "a young man of fine presence, most agreeable manners and... in the early twenties." (2)

In the 1929 General Election the Conservative Party candidate, David Margesson argued that the only way to defeat the "evils of socialism" was to vote for him. Margesson won comfortably and Bernays came last. He was magnanimous in defeat and claimed that although "individual Liberals may be defeated.... Liberalism is never beaten." (3)

Robert Bernays - Journalist

Bernays also lost his job when the Daily News became the Daily Chronicle. In the summer of 1930, he travelled with the then leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Lords, William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp, to Australia. Although married Lygon appears to be having a homosexual relationship with Bernays. Homosexual practice was a criminal offence at the time, and Hugh Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster, a strong supporter of the Conservative Party, told King George V about the relationship and it was rumoured to have said, "I thought men like that shot themselves". In order to avoid prison Lygon agreed to go into exile. (4) Bernays now moved to India where he wrote his first book The Naked Fakir (1931), which provided the first British study of Gandhi. (5)

Bernays was considered a talented writer. Jean Campbell said that there has never been anyone "who could make out of the drearist material... such side-splitting, ridiculous, heavenly fun." (6) In social situations he was very shy and suffered from a pronounced stutter. He was also worried he would be exposed as a homosexual. Chris Bryant, the author of The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler (2020) has pointed out that the Earl Beauchamp story had a major impact on his thinking: "Beauchamp's fate taught Rob a horrible lesson - that if you sailed too close to the wind you risked being hounded out of society... The message was rammed home to Rob - same-sex longings could only bring trouble and loneliness." (7)

Nazi Germany

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. Ramsay MacDonald, the former Labour Party prime-minister, led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. Robert Bernays stood for the National Liberals in Bristol North and as he was unopposed by a Conservative, he won the seat with a 13,000 majority. (8) The Government parties polled 14,500,000 votes to Labour's 6,600,000. In the new House of Commons, the Labour Party had only 52 members and the Lloyd George Liberals held only 4 seats. (9) As Harold Nicolson pointed out it was "most disquieting that at this crisis of our history we should have a purely one-party House of Commons." (10)

In September 1932, Bernays visited Nazi Germany. He took with him his oldest and closest friend from university days, Frank Milton, a wealthy bachelor and successful lawyer. The two men went on "a tour of the queer bars, cafes and clubs." Bernays wrote in his journal that they went to one club "as to the nature of which there was absolutely no doubt... middle-aged men were dancing with boys not out of their teens, and young men with powdered faces and swaying hips sidled up and down in women's evening dress." He added: "I imagine that such a place could be paralleled in London, but at least it would be down some dingy back stairs, and the proprietor would be in constant terror of raids by the police." (11)

Bernays saw Adolf Hitler speak at a public meeting. In other circumstances, he commented, one might think he was no more than "a hard-working scout master out for the day" but once he addressed the crowd he became something else: "The moment he began to speak he was transformed from a vulgar, self-advertising politician to an orator, a prophet with a flaming mission to his people." On his return to Bristol he told a meeting: "In Germany today there are all the elements of a resurgent militarism". (12)

After the 1933 General Election, Chancellor Adolf Hitler proposed an Enabling Bill that would give him dictatorial powers. Such an act needed three-quarters of the members of the Reichstag to vote in its favour. All the active members of the Communist Party, were in prison, in hiding, or had left the country (an estimated 60,000 people left Germany during the first few weeks after the election). This was also true of most of the leaders of the other left-wing party, Social Democrat Party (SDP). However, Hitler still needed the support of the Catholic Centre Party (BVP) to pass this legislation. Hitler therefore offered the BVP a deal: vote for the bill and the Nazi government would guarantee the rights of the Catholic Church. The BVP agreed and when the vote was taken on 24th March, 1933, only 94 members of the SDP voted against the Enabling Bill. (13)

In June 1933, Bernays returned to Germany and had a meeting with Edmund Heines, Chief Commissioner of the Police in Breslau and deputy to Ernst Röhm, the head of the Sturmabteilung (SA). Although he admitted that Heines "had, so far as the atrocities were concerned, the most evil and extraordinary reputation in all Germany" Bernays found him an attractive man. "Heines appeared a charming fellow - young, about thirty-five years of age, fair hair, blue eyes, smiling, boyish... he was such a fine figure of a man that it reminded me of an English staff officer, or the captain of a rugby fifteen who has just been made head boy... He was gloriously self-confident, so naively exultant in his new sense of power.... Heines had all the attributes that make for hero-worship... They (Nazi leaders) had homosexuality and sadism written all over them." (14)

Heines took Bernays to Breslau concentration camp that had been created to provide "protective custody" for Silesian Jews and members of the Communist Party (KPD) and Social Democrat Party (SDP). "This was a prison and the inmates were given backbreaking and nugatory tasks. One group was turning a marshy wasteland into municipal baths... Another was watering plants by the barbed wire in the shape of a swastika. When the visitors approached an inmate he would mechanically repeat the line that the work was hard but they were getting used to it and that they were well fed. If there were questions about a prisoner who had never been heard of again, the stock answer was trundled out: 'Shot while trying to escape'." (15)

Bernays was constantly aware of signs in Germany saying "Jews excluded". He also heard desperate tales of German Jews being forced to leave all their money and possessions behind when they fled. Bernays was shocked by Heines's insistence that Europe was threatened by a very formidable communist peril and his justification of the attack on the Jews on the grounds that "Jewish money was behind it all." (16) He later commented: "I cannot get out of my mind, even now, the expression of terror on the faces of so many with whom we talked." (17)

In a series of articles in the Daily Chronicle, Contemporary Review and the Western Daily Press he wrote about Hitler's government. In September 1933, he argued that the "atrocities today are more calculated and systematic". (18) He suggested that the problem was the "pre-war spirit of arrogance and the feeling that the Germans were the children of the earth". (19) In November he warned that Germany was an "armed camp" and "if this spirit is allowed to continue, it means war in ten years." (20)

However, in his book, Special Correspondent (1934), Bernays he did seem to support the anti-semitism taking place in Nazi Germany: "There is something in the contention that the German Jews have made little attempt to understand the German national psychology" and that it was "unfortunate that, since the war, the best seats at the theatre, the most expensive restaurants, the most luxurious cars, have been in the possession of the Jews". (21)

Bernays visited Germany again in May 1934. This time he went with Ronald Tree, the Conservative Party MP for Harborough. Tree contacted his friend, Otto Christian Archibald von Bismarck, a member of the Nazi Party, and asked if he could arrange meetings with leading members of the government in Germany. He replied: "If you go to Germany with a Jew, a Liberal and a liar, then I will do nothing whatever to help you, and will in fact see that you meet as few people as possible." (22) Bernays told the West London Synagogue Association, that he was shocked when "his own slight Jewish ancestry" was constantly brought up like this. (23)

On their arrival in Nazi Germany they sent a message to Ernst Hanfstaengl, one of Hitler's close advisors, in an attempt to meet government ministers. Hanfstaengl replied that he considered Bernays a "Bolshevik Jew" and should be deported. It was made clear that as a Jew he was not wanted in Nazi Germany. This came us a suprise to Bernays as he was "not a Jew by religion - and only remotely by race". Bernays felt he was made unwelcome when he visited the British Embassy in Berlin who received him as if he was "a bomb that might explode at any moment". (24)

Night of the Long Knives

A month after Bernays arrived back in England, Hitler moved against the homosexual leadership of the Sturmabteilung (SA). On the evening of 28th June, 1934, Hitler telephoned Ernst Röhm to convene a conference of the SA leadership at Hanselbauer Hotel in Bad Wiesse, two days later. "The call served the double purpose of gathering the SA chiefs in one out-of-the-way spot, and reassuring Röhm that, despite the rumours flying about, their mutual compact was safe. No doubt Röhm expected the discussion to centre on the radical change of government in his favour promised for the autumn." (25)

At around 6.30 in the morning of 30th June, Hitler arrived at the hotel in a fleet of cars full of armed Schutzstaffel (SS) men. (26) Erich Kempka, Hitler's chauffeur, witnessed what happened: "Hitler entered Röhm's bedroom alone with a whip in his hand. Behind him were two detectives with pistols at the ready. He spat out the words; Röhm, you are under arrest. Röhm's doctor comes out of a room and to our surprise he has his wife with him. I hear Lutze putting in a good word for him with Hitler. Then Hitler walks up to him, greets him, shakes hand with his wife and asks them to leave the hotel, it isn't a pleasant place for them to stay in, that day. Now the bus arrives. Quickly, the SA leaders are collected from the laundry room and walk past Röhm under police guard. Röhm looks up from his coffee sadly and waves to them in a melancholy way. At last Röhm too is led from the hotel. He walks past Hitler with his head bowed, completely apathetic." (27)

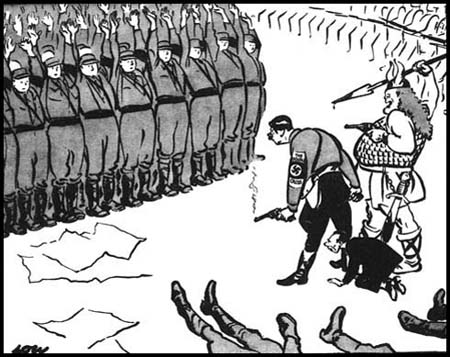

Edmund Heines was found in bed with his chauffeur. (28) According to eyewitnesses, Hitler ordered the "ruthless extermination of this pestilential tumour." Heines and his young companion were dragged from the room and shot and became the first victims of the Night of the Long Knives. (29) It is not known how many people were murdered between 30th June and 2nd July, when Hitler called off the killings. Adolf Hitler admitted to 76, but the real number is probably nearer 200 or 250. "Bodies were found in fields and woods for weeks afterwards and files of petitions from relatives of the missing remained active for months. What seems certain is that less than half were SA officers." (30)

Adolf Hitler announced that Ernst Röhm had been killed because he had "broken all laws of decent contact". He had created a sect within the SA "sharing a common orientation, who formed the kernal of a conspiracy not only against the moral conceptions of a healthy Volk, but also against state security". Röhm was also accused of promoting men "without regard to National Socialist and SA service, but only because they belonged to the circle of this orientation". (31) Joseph Goebbels made the same point when he said Röhm and his cronies had led a life of unparalleled debauchery" and had come close to tainting the entire leadership of the party "with their shameful and disgusting sexual aberrations." (32)

The Daily Mail praised Hitler for taking such action: "Herr Adolf Hitler, the German Chancellor, has saved his country. Swiftly and with exorable severity, he has delivered Germany from men who had become a danger to the unity of the German people and to the order of the state. With lightening rapidity he has caused them to be removed from high office, to be arrested, and put to death. The names of the men who have been shot by his orders are already known. Hitler's love of Germany has triumphed over private friendships and fidelity to comrades who had stood shoulder to shoulder with him in the fight for Germany's future." (33)

The Times welcomed the fact that "the Führer has started cleaning up" but could not understand the timing as "the offences of Röhm and his associates were admittedly known for years, the 'clean up' was not undertaken long ago." (34) The Manchester Guardian welcomed the fact that "the criminal lunatics, or some of them, have been destroyed." (35) Only the journalist Sefton Delmer, who was based in Berlin working for the Daily Express gave a critical account of what happened and published a list of those murdered. This resulted in him being expelled from Germany." (36)

Bernays was at a party with Anthony Eden, who was then the Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs. Eden welcomed the purge as he believed that it "means a more stable Europe". Bernays wrote in his journal, "There was no other expression but delight that Röhm was dead... How callous this generation is getting about human life." (37) Robert Boothby sided with Bernays: "One thing, we all agreed (anti-appeasement Tory MPs), had emerged from the shocking and squalid events of the day. The Nazis had been shown up for what they in fact were - unscrupulous and bloodthirsty gangsters. In future they should be treated as such." (38)

Appeasement

In the 1935 General Election Bernays stood as "Liberal independent of all groups in the party" but was elected with a reduced majority. In September 1936 he gave his support to the National Government and in May 1937 Neville Chamberlain appointed him as parliamentary secretary to the minister of health. In this way he became one of the band of non-Conservative MPs serving in Chamberlain's administration. (39)

Robert Bernays was an opponent of appeasement. Anthony Eden eventually resigned as foreign secretary over this issue. On 20th February 1938, Eden told the House of Commons: "I do not believe that we can make progress in European appeasement if we allow the impression to gain currency abroad that we yield to constant pressure. I am certain in my own mind that progress depends above all on the temper of the nation, and that temper must find expression in a firm spirit. This spirit I am confident is there. Not to give voice it is I believe fair neither to this country nor to the world." (40)

Major George Joseph Ball persuaded the BBC to relegate Eden's resignation to the second story on the evenings bulletins and to say nothing at all about Germany or Italy. The Daily Mail, the Evening Standard, the Daily Express and the Daily Telegraph all supported Chamberlain against Eden. (41) The Times claimed that "his policy of appeasement, which is also the policy of peace." (42) The Manchester Guardian, not under the control of Major Ball, noted that although a resignation of this kind might have precipitated a major government crisis, the press had "preserved a unity of silence that could hardly be bettered in a totalitarian state." (43)

Over twenty Tory MPs abstained following the debate on appeasement. This included Ronald Cartland, Winston Churchill, Harold Macmillan, Brendan Bracken, Edward Spears, Jack Macnamara, Jim Thomas, Ronald Tree, Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, Paul Emrys-Evans and Vyvyan Adams. Robert Bernays was tempted to resign but as he was paid £1,500 in addition to the £600 he received as an MP, the equivalent in 2020 prices to an additional £100,000 a year, he felt he could not afford to make this decision. (44)

In private Bernays was opposed to appeasement but was unwilling to criticise the government in public. In a letter to his sister he explained the difficulties of getting an agreement with Adolf Hitler over Czechoslovakia: "Such a proposal (cession)is, of course, an impossibility: the territory where the Germans live in Czechoslovakia affords a highly defensible frontier, and to surrender it would be for the Czechs to place themselves at the mercy of the Germans who could then do what they liked there and in eastern Europe." (45)

Bernays stayed in office after the Munich Agreement but told his friends that it was better to argue from within the government than without. He stated in the House of Commons that "there is an increasing tendency to criticise the PM's actions at Munich and to forget how overwhelming was the sense of relief that his personal intervention had given us peace." He added: "You cannot defend liberty merely by making perorations about it... You need guns and the men to man them. You need air raid posts and the nurses to staff them, you need stretchers and the people to carry them." (46)

Although a homosexual Bernays decided he would marry. In 1938 he met Clementine Freeman-Mitford. He admitted that she was "pretty, unpretentious, charming and very, very keen on politics" and was "fanatically anti-Hitler". However, Clementine eventually married Sir Alfred Beit, the Conservative Party MP for St. Pancras. Bernays wrote to a friend "I feel in despair and may be a victim to anyone on the rebound." (47)

Second World War

In a debate in the House of Commons on 7th May, 1940, Leo Amery, the Conservative Party MP argued in the House of Commons: "Just as our peace-time system is unsuitable for war conditions, so does it tend to breed peace-time statesmen who are not too well fitted for the conduct of war. Facility in debate, ability to state a case, caution in advancing an unpopular view, compromise and procrastination are the natural qualities - I might almost say, virtues - of a political leader in time of peace. They are fatal qualities in war. Vision, daring, swiftness and consistency of decision are the very essence of victory." Looking at Neville Chamberlain he then went onto quote what Oliver Cromwell said to the Long Parliament when he thought it was no longer fit to conduct the affairs of the nation: "You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go." (48)

The following day, Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party demanded a vote of no confidence in Chamberlain. The 77 year-old David Lloyd George, was one of those MPs who called on the prime minister to resign. The government defeated the Labour motion by 281 to 200 votes. But the abstention of 134 Tory MPs indicated the extent to which the government had haemorrhaged authority. It was clear that drastic changes were essential if the government was to restore its authority. Chamberlain invited Attlee to join a National Government but he refused and said he would only accept if the prime minister resigned. (49)

Chamberlain told King George VI that he had no choice but to resign. In his diary he wrote: "The Amerys, Duff Coopers, and their lot are consciously, or unconsciously, swayed by a sense of frustration because they can only look on, and finally the personal dislike of Simon and Hoare had reached a pitch which I find it difficult to understand, but which undoubtedly had a great deal to do with the rebellion. A number of those who voted against the government have since either told me, or written to me to say, that they had nothing against me except that I had the wrong people in my team." (50)

The King and Chamberlain wanted Lord Halifax to become prime minister. Halifax had the support of some Labour MPs like Hugh Dalton and Herbert Morrison, but not Attlee who wanted Churchill. The King attempted to insist on Halifax but eventually he agreed to ask Winston Churchill to become prime minister. As Clive Ponting, the author of Winston Churchill (1994) pointed out: "It was perhaps the crowning irony of his career that he should become Prime Minister because of the need to bring the Labour Party, which had so far only formed two minority governments, into a national coalition. One of the main motivating forces of his political life in the previous twenty years was his outright opposition to the claims of Labour and the trade unions, reflected in his often expressed belief that not only were they unfit to govern the country but that they were engaged in a campaign to subvert its political, economic and social institutions." (51)

Churchill saw Bernays as a Chamberlain loyalist and sacked him from the government but did appoint him as deputy regional commissioner for the Southern Civil Defence Region on an annual salary of £1,200. Bernays also paid a doctor six guineas to give him a "thumpingly adverse report", which concluded that he was "quite unfit for general service". He told a friend that the doctor had certainly been worth his fee. However, after the death of his eldest brother, Jack Bernays on active service he decided to enlist. (52)

On 25th April 1942, Bernays married Nancy Britton, the daughter of George Britton, the former Liberal Party MP for Bristol East. Promoted to the rank of captain he was an "entertainment officer" at Horfield Barracks in Bristol. This involved making patriotic speeches to troops. In January, 1945, Bernays joined a cross-party group of MPs who were asked to boost the morale of British troops in Italy. (53)

Robert Bernays, at the age of forty-two, was killed in an air crash off Brindisi on 25th January 1945.

Primary Sources

(1) Nick Smart, Robert Bernays : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (24th May 2007)

After standing unsuccessfully as Liberal candidate for Rugby in 1929, Bernays had more luck in Bristol North in 1931. There, despite his hurried adoption and advocacy of free trade, he was unopposed by a Conservative and won the seat with a 13,000 majority. Before his election he had collected material as News Chronicle special correspondent in India for his first book, a study of Gandhi, Naked Fakir (1933), while after entering the Commons he used his status as an MP to advantage by travelling throughout Europe as a highly paid journalist. His second book, Special Correspondent (1934), consisted largely of an account of the beginnings of the Nazi regime in Germany, which he had visited in 1933.

Politics and journalism did not always combine well, however. Bernays's decision in November 1933 not to follow his party leader, Sir Herbert Samuel, into opposition to the National Government cost him his job at the News Chronicle. Though something of an impoverished political orphan for the remainder of the 1931–5 parliament, Bernays obviously enjoyed politics and the company of politicians. His sense - however precarious - of being close to the centre of things emerges clearly in the diary he maintained and in his letters to his sister, Lucy, who was living in Brazil. These, in edited form and covering the years 1932 to 1939, were published in 1996. They plot not merely the career of a young and ambitiously earnest politician, but also the tensions and uncertainties of politics in the 1930s. In throwing off his free-trading Liberal Party hat, Bernays had invested heavily in the National Government's survival. Calculating correctly that the route to promotion lay in joining the Liberal Nationals he did so, and reward, when it came, took the form of his being appointed parliamentary secretary to the minister of health in May 1937. In this way he became one of the band of non-Conservative MPs serving in Chamberlain's administration. But the beneficiary of one form of coalitionism in British politics became the casualty of another. Hard-working though Bernays was, he was dropped as soon as Churchill formed his coalition government in May 1940.

Serving thereafter as deputy commissioner for the southern civil defence region, Bernays made two decisions in April 1942. One was to join the army and take a commission with the Royal Engineers. The other was to marry, on 26 April, Nancy Britton (d. 1984), the daughter of a constituent. The couple had two sons, neither of whom have any memory of their father. At the age of forty-two, while a member of a parliamentary team visiting troops in the Mediterranean, he was killed in an air crash off Brindisi on 25 January 1945.

By 1945 there was not much future for National Liberalism, and had he lived to contest Bristol North in the general election of that year Bernays would doubtless have been defeated. His political career would probably have ended then anyway. Although his life was cut short, he should be remembered as both creature and chronicler of an unusual phase in national politics: the period of National Government. In life his achievements were considerable without being exceptional. As an unattached and amusing young man he featured in the pre-war London scene. In death, however, he left in his diary and letters one of the fullest and most colourful accounts of a distinct political regime. In common with other noted political diarists (Cuthbert Headlam, Harold Nicolson, Henry (Chips) Channon, and, most recently, Alan Clark) he never rose above junior office status. Perhaps that level offers the best vantage point for a diarist.

Student Activities

References

(1) Nick Smart, Robert Bernays : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (24th May 2007)

(2) Rugby Advertiser (9th September 1927)

(3) Rugby Advertiser (18th June 1929)

(4) Paula Byrne, Times Literary Supplement (9th August, 2009)

(5) Nick Smart, Robert Bernays : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (24th May 2007)

(6) Jean Campbell, letter to Nancy Bernays (2nd February 1945)

(7) Chris Bryant, The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler (2020) pages 90-90

(8) Nick Smart, Robert Bernays : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (24th May 2007)

(9) Martin Pugh, Speak for Britain: A New History of the Labour Party (2010) page 216

(10) Harold Nicolson, diary entry (October, 1931)

(11) Robert Bernays, journal entry (September 1932)

(12) Western Daily Press (17th December 1932)

(13) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 84

(14) Robert Bernays, journal entry (June 1933)

(15) Chris Bryant, The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler (2020) page 120

(16) Robert Bernays, journal entry (6th June 1933)

(17) Robert Bernays, Special Correspondent (1934) page 239

(18) Contemporary Review (November 1933)

(19) Western Daily Press (15th November 1933)

(20) Western Daily Press (23rd November 1933)

(21) Robert Bernays, Special Correspondent (1934) page 234

(22) Chris Bryant, The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler (2020) page 120

(23) Robert Bernays, journal entry (19th May 1934)

(24) Chris Bryant, The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler (2020) page 139

(25) Peter Padfield, Himmler: Reichsfuhrer S.S. (1991) page 156

(26) Richard Overy, The Third Reich: A Chronicle (2010) page 101

(27) Erich Kempka, interviewed in 1946.

(28) Paul R. Maracin, The Night of the Long Knives: Forty-Eight Hours that Changed the History of the World (2004) pages 120-122

(29) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 298

(30) Peter Padfield, Himmler: Reichsfuhrer S.S. (1991) page 159

(31) Adolf Hitler, speech in the Reichstag (13th July, 1934)

(32) Max Gallo, The Night of Long Knives (1972) page 264

(33) The Daily Mail (2nd July, 1934)

(34) The Times (3rd July, 1934)

(35) The Manchester Guardian (2nd July, 1934)

(36) Sefton Delmer, Daily Express (4th July, 1934)

(37) Robert Bernays, journal entry (2nd July, 1934)

(38) Chris Bryant, The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler (2020) pages 143-144

(39) Nick Smart, Robert Bernays : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (24th May 2007)

(40) Anthony Eden, speech (21st February 1938)

(41) Chris Bryant, The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler (2020) page 219

(42) The Times (22nd February, 1938)

(43) The Manchester Guardian (24th February, 1938)

(44) Chris Bryant, The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler (2020) pages 222-224

(45) Robert Bernays, letter to Lucy Brereton (9th September, 1938)

(46) Robert Bernays, speech in the House of Commons (16th December, 1938)

(47) Chris Bryant, The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler (2020) page 272

(48) Leo Amery, speech in the House of Commons (7th May, 1940)

(49) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 240

(50) Neville Chamberlain, diary entry (11th May, 1940)

(51) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 431

(52) Chris Bryant, The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler (2020) page 357

(53) Nick Smart, Robert Bernays : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (24th May 2007)