Edward Bocking

Edward Bocking was born in about 1480. He joined Canterbury Cathedral Priory as a Benedictine monk in 1500. Four years later he was admitted a scholar to Oxford University and became warden of Canterbury College in 1510. He later became a cellarer at Canterbury Cathedral. (1)

In 1526 Bocking and William Hadley were asked by Archbishop William Warham, to investigate Elizabeth Barton, a servant in the household of a certain Thomas Cobb, in the village of Aldington, some 20 miles from Canterbury. Their task was "to see this woman, and see what trances she had." (2) The case had been reported by Edward Thwaites: "It happened a certain maiden named Elizabeth Barton... to be touched with a great infirmity in her body, which did ascend at diverse times up into her throat, and swelled greatly, during the time whereof she seemed to be in grievous pain, in so much as a man would have thought that she had suffered the pangs of death itself, until the disease descended and fell down into the body again." (3)

According to Barton's biographer, Diane Watt: "In the course of this period of sickness and delirium she began to demonstrate supernatural abilities, predicting the death of a child being nursed in a neighbouring bed. In the following weeks and months the condition from which she suffered, which may have been a form of epilepsy, manifested itself in seizures (both her body and her face became contorted), alternating with periods of paralysis. During her death-like trances she made various pronouncements on matters of religion, such as the seven deadly sins, the ten commandments, and the nature of heaven, hell, and purgatory. She spoke about the importance of the mass, pilgrimage, confession to priests, and prayer to the Virgin and the saints." (4)

Edward Bocking and Elizabeth Barton

By October 1528, Elizabeth Barton's visions began to concentrate on controversal issues. It is claimed that during this period Edward Bocking encouraged her to speak out against the religious reformers inspired by the writings of Martin Luther and to complain about the plans for Henry VIII to divorce Catherine of Aragon. To further this scheme he had her removed to the St Sepulchre's Nunnery at Canterbury. "Bocking... is said to have induced her to declare herself an inspired emissary for the overthrow of Protestantism and the prevention of the divorce of Queen Catherine.... There is little doubt that he was her chief instigator in the continuance of her career of deception. His share in the affair, though it cannot be excused, must be ascribed to a mistaken zeal for the preservation of the ancient Faith." (5)

However, Bocking's biographer, Ethan H. Shagan, has claimed that his role in this is not conclusive. "Barton... turned to politics, agitating against Henry VIII's plan to annul his marriage to Katherine of Aragon, and from the beginning of these activities Bocking was her closest confidant. His most important role, however, was as a publicist for Barton. He was often accused, both by Henry VIII's government and by later historians, of having concocted rather than merely disseminated her revelations. It is impossible to tell whether there is substance in the charge but it has the appearance of misogyny, and certainly the government benefited greatly by using it to undermine the commonplace assumption that Barton's revelations must have been holy because a woman could not normally have had the wits to invent them on her own." (6)

Edward Thwaites reported that a crowd of about 3,000 people attended one of the meetings where she told of her visions. Other sources say it was 2,000 people. Sharon L. Jansen points out: "In either case there was a sizable gathering at the chapel, indicating something of how quickly and widely reports of her visions had spread." (7) Thomas Cranmer was one of those who saw Barton. He wrote a letter to Hugh Jenkyns explaining that he had seen "a great miracle" that had been created by God: "Her trance lasted... the space of three hours and more... Her face was wonderfully disfigured, her tongue hanging out... her eyes were... in a manner plucked out and laid upon her cheeks... a voice was heard... speaking within her belly, as it had been in a cask... her lips not greatly moving.... When her belly spoke about the joys of heaven... it was in a voice... so sweetly and so heavenly that every man was ravished with the hearing thereof... When she spoke of hell... it put the hearers in great fear." (8)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey arranged for Elizabeth Barton to see Henry VIII. She told him to burn English translations of the Bible and to remain loyal to the Pope. Elizabeth then warned the King that if he married Anne Boleyn he would die within a month and that within six months the people would be struck down by a great plague. He was disturbed by her prophesies and ordered that she be kept under observation. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer commented later that Henry put off his marriage to Anne because "of her visions". (9) William Tyndale was less convinced by her trances and claimed that her visions were either feigned or the work of the devil. (10)

In October 1532, Henry VIII agreed to meet Elizabeth Barton again. According to the official record of this meeting: "She (Elizabeth Barton) had knowledge by revelation from God that God was highly displeased with our said Sovereign Lord (Henry VIII)... and in case he desisted not from his proceedings in the said divorce and separation but pursued the same and married again, that then within one month after such marriage he should no longer be king of this realm, and in the reputation of Almighty God should not be king one day nor one hour, and that he should die a villain's death." (11)

Soon afterwards the King discovered that Anne Boleyn was pregnant. As it was important that the child should not be classed as illegitimate, arrangements were made for Henry and Anne to get married. King Charles V of Spain threatened to invade England if the marriage took place, but Henry ignored his threats and the marriage went ahead on 25th January, 1533. It was very important to Henry that his wife should give birth to a male child. Without a son to take over from him when he died, Henry feared that the Tudor family would lose control of England.

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Sir Thomas More was careful to make it clear that despite his growing opposition to the King's church policies, he accepted Henry's marriage to Anne Boleyn as being part of God's providence, and would neither "murmur at it nor dispute upon it", since "this noble woman" was "royally anointed queen". (12) In the summer of 1533 Thomas More met Elizabeth Barton. Soon afterwards he wrote to her warning about the dangers she faced if she continued to speak with "lay persons, of any such manner things as pertain to princes' affairs, or the state of the realm... with any person, high and low, of such manner things as may to the soul be profitable for you to show and for them to know". (13)

During this period Edward Bocking produced a book detailing Barton's revelations. In 1533 a copy of Bocking's manuscript was made by Thomas Laurence of Canterbury, and 700 copies of the book were issued by the printer John Skot, who supplied 500 copies to Bocking. Thomas Cromwell discovered what was happening and ordered that all copies were seized and destroyed. This operation was successful and no copies of the book exists today. (14)

Arrest of Edward Bocking

In the summer of 1533 Archbishop Thomas Cranmer wrote to the prioress of St Sepulchre's Nunnery asking her to bring Elizabeth Barton to his manor at Otford. On 11th August she was questioned, but was released without charge. Thomas Cromwell then questioned her and, towards the end of September, Edward Bocking was arrested and his premises were searched. Bocking was accused of writing a book about Barton's predictions and having 500 copies published. (15) Father Hugh Rich was also taken into custody. In early November, following a full scale investigation, Barton was imprisoned in the Tower of London. (16)

Elizabeth Barton was examined by Thomas Cromwell, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Bishop Hugh Latimer. During this period she had one final vision "in which God willed her, by his heavenly messenger, that she should say that she never had revelation of God". In December 1533, Cranmer reported "she confessed all, and uttered the very truth, which is this: that she never had visions in all her life, but all that ever she said was feigned of her own imagination, only to satisfy the minds of them the which resorted unto her, and to obtain worldly praise." (17)

Peter Ackroyd, the author of Tudors (2012) has suggested that Barton had been tortured: "It may be that she was put on the rack. In any case it was declared that she had confessed that all her visions and revelations had been impostures... It was then determined that the nun should be taken throughout the kingdom, and that she should in various places confess her fraudulence." (18) Barton secretly sent messages to her adherents that she had retracted only at the command of God, but when she was made to recant publicly, her supporters quickly began to lose faith in her. (19)

Eustace Chapuys, reported to King Charles V on 12th November, 1533, on the trial of Elizabeth Barton: "The king has assembled the principal judges and many prelates and nobles, who have been employed three days, from morning to night, to consult on the crimes and superstitions of the nun and her adherents; and at the end of this long consultation, which the world imagines is for a more important matter, the chancellor, at a public audience, where were people from almost all the counties of this kingdom, made an oration how that all the people of this kingdom were greatly obliged to God, who by His divine goodness had brought to light the damnable abuses and great wickedness of the said nun and of her accomplices, whom for the most part he would not name, who had wickedly conspired against God and religion, and indirectly against the king." (20)

A temporary platform and public seating was erected at St. Paul's Cross and on 23rd November, 1533, Edward Bocking and Elizabeth Barton made a full confession in front of a crowd of over 2,000 people. Barton said: "I, Dame Elizabeth Barton, do confess that I, most miserable and wretched person, have been the original of all this mischief, and by my falsehood have grievously deceived all these persons here and many more, whereby I have most grievously offended Almighty God and my most noble sovereign, the King's Grace. Wherefore I humbly, and with heart most sorrowful, desire you to pray to Almighty God for my miserable sins and, ye that may do me good, to make supplication to my most noble sovereign for me for his gracious mercy and pardon." (21)

Over the next few weeks Elizabeth Barton repeated the confession in all the major towns in England. It was reported that Henry VIII did this because he feared that Barton's visions had the potential to cause the public to rebel against his rule: "She... will be taken through all the towns in the kingdom to make a similar representation, in order to efface the general impression of the nun's sanctity, because this people is peculiarly credulous and is easily moved to insurrection by prophecies, and in its present disposition is glad to hear any to the king's disadvantage." (22)

Execution of Edward Bocking and Elizabeth Barton

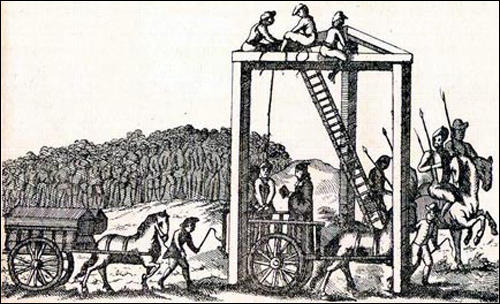

Parliament opened on 15th January 1534. A bill of attainder charging Elizabeth Barton, Edward Bocking, Henry Risby (warden of Greyfriars, Canterbury), Hugh Rich (warden of Richmond Priory), Henry Gold (parson of St Mary Aldermary) and two laymen, Edward Thwaites and Thomas Gold, with high treason, was introduced into the House of Lords on 21st February. It was passed and then passed by the House of Commons on 17th March. (23) They were all found guilty and sentenced to be executed on 20th April, 1534. They were "dragged through the streets from the Tower to Tyburn". (24)

On the scaffold she told the assembled crowd: "I have not been the cause of my own death, which most justly I have deserved, but also I am the cause of the death of all these persons which at this time here suffer. And yet, to say the truth, I am not so much to be blamed considering it was well known unto these learned men that I was a poor wench without learning - and therefore they might have easily perceived that the things that were done by me could not proceed in no such sort, but their capacities and learning could right well judge from whence they proceeded... But because the things which I feigned was profitable unto them, therefore they much praised me... and that it was the Holy Ghost and not I that did them. And then I, being puffed up with their praises, feel into a certain pride and foolish fantasy with myself." (25)

John Husee witnessed their deaths: "This day the Nun of Kent, with two Friars Observants, two monks, and one secular priest, were drawn from the Tower to Tyburn, and there hanged and headed. God, if it be his pleasure, have mercy on their souls. Also this day the most part of this City are sworn to the King and his legitimate issue by the Queen's Grace now had and hereafter to come, and so shall all the realm over be sworn in like manner." (26)

The executions were clearly intended as a warning to those who opposed the king's policies and reforms. Elizabeth Barton's head was impaled on London Bridge while the head of Edward Bocking was placed on one of the gates of the city. (27)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Primary Sources

(1) G. C. Alston, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912)

English Benedictine, b. of East Anglian parentage, end of fifteenth century; d. 20 April, 1534. He graduated B.D. at Oxford, in 1513, and D.D. in 1518, was for some time Warden of Canterbury College there, and became a monk at Canterbury 1526. When Elizabeth Barton, "The Holy Maid of Kent", commenced her alleged Divine revelations, Bocking, with another monk, was sent to examine and report upon their authenticity, and he is said to have induced her to declare herself an inspired emissary for the overthrow of Protestantism and the prevention of the divorce of Queen Catherine. To further this scheme he had her removed to the Convent of St. Sepulchre at Canterbury. There is little doubt that he was her chief instigator in the continuance of her career of deception. His share in the affair, though it cannot be excused, must be ascribed to a mistaken zeal for the preservation of the ancient Faith. After the divorce of Queen Catherine and Henry's marriage to Anne Boleyn in 1533, Cromwell had Elizabeth Barton arrested, together with Bocking and others.

(2) Ethan H. Shagan, Edward Bocking : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

By October 1528 Barton had turned to politics, agitating against Henry VIII's plan to annul his marriage to Katherine of Aragon, and from the beginning of these activities Bocking was her closest confidant. His most important role, however, was as a publicist for Barton. He was often accused, both by Henry VIII's government and by later historians, of having concocted rather than merely disseminated her revelations. It is impossible to tell whether there is substance in the charge but it has the appearance of misogyny, and certainly the government benefited greatly by using it to undermine the commonplace assumption that Barton's revelations must have been holy because a woman could not normally have had the wits to invent them on her own.

(3) John Husee, diary entry (20th April, 1534)

This day the Nun of Kent, with two Friars Observants, two monks, and one secular priest, were drawn from the Tower to Tyburn, and there hanged and headed. God, if it be his pleasure, have mercy on their souls. Also this day the most part of this City are sworn to the King and his legitimate issue by the Queen's Grace now had and hereafter to come, and so shall all the realm over be sworn in like manner.

Student Activities

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Codes and Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)