On this day on 23rd March

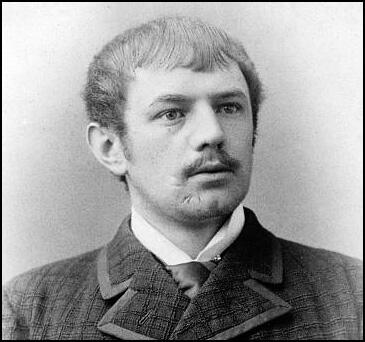

On this day in 1868 Dietrich Eckart was born in Neumarkt, Germany. His mother Anna Eckart, died when he was young and he had a difficult childhood being expelled from several schools. His father, Christian Eckart, a successful lawyer, also died and left him a sizeable amount of money.

Eckart studied medicine but left before he obtained his degree. For the next few years he attempted to make a living from writing plays and poems. After spending his family inheritance he found work as a journalist. Eckart developed right wing views and associated with members of the Thule Society.

Konrad Heiden, was a journalist working in Munich who investigated the life of Eckart: "Born of well-to-do parents in a little town of northern Bavaria, he had been a failure as a law student because he had drunk too much and worked too little. Then in Berlin - already in his forties - he had led the life of a vagrant who believes himself to be a poet.... He had grown to be a morphine addict and had spent some time in an asylum for the mentally diseased, where his theatrical gifts finally found a haven, for he had staged plays there and used the inmates as actors."

Eckart opposed the German Revolution in 1918 which he regarded as Jewish-inspired. He also edited the anti semitic periodical Auf gut Deutsch. During this period he became friends with Alfred Rosenberg. In January 1919 he joined with Hermann Esser, Gottfried Feder and Karl Harrer, to form the German Workers Party (GPW). Harrer was elected as chairman of the party. Eckart pointed out: "We need a fellow at the head who can stand the sound of a machine gun. The rabble need to get fear into their pants. We can't use an officer, because the people don't respect them any more. The best would be a worker who knows how to talk... He doesn't need much brains.... He must be a bachelor, then we'll get the women."

On 30th May, 1919, Captain Karl Mayr, was appointed as head of the Education and Propaganda Department. He was given considerable funds to build up a team of agents and informants. On 12th September, Mayr sent Adolf Hitler to attend a meeting of the German Workers Party (GWP). Hitler recorded in Mein Kampf (1925): "When I arrived that evening in the guest room of the former Sternecker Brau (Star Corner)... I found approximately 20–25 persons present, most of them belonging to the lower classes. The theme of Feder’s lecture was already familiar to me; for I had heard it in the lecture course... Therefore, I could concentrate my attention on studying the society itself. The impression it made upon me was neither good nor bad. I felt that here was just another one of these many new societies which were being formed at that time. In those days everybody felt called upon to found a new Party whenever he felt displeased with the course of events and had lost confidence in all the parties already existing. Thus it was that new associations sprouted up all round, to disappear just as quickly, without exercising any effect or making any noise whatsoever."

Hitler discovered that the party's political ideas were similar to his own. He approved of Drexler's German nationalism and anti-Semitism but was unimpressed with what he saw at the meeting. Hitler was just about to leave when a man in the audience began to question the logic of Feder's speech on Bavaria. Hitler joined in the discussion and made a passionate attack on the man who he described as the "professor". Drexler was impressed with Hitler and gave him a booklet encouraging him to join the GWP. Entitled, My Political Awakening, it described his objective of building a political party which would be based on the needs of the working-class but which, unlike the Social Democratic Party (SDP) or the German Communist Party (KPD) would be strongly nationalist.

Anton Drexler had mixed feelings about Hitler but was impressed with his abilities as an orator and invited him to join the party. Adolf Hitler commented: "I didn't know whether to be angry or to laugh. I had no intention of joining a ready-made party, but wanted to found one of my own. What they asked of me was presumptuous and out of the question." However, Hitler was urged on by his commanding officer, Major Karl Mayr, to join. Hitler also discovered that Ernst Röhm, was also a member of the GWP. Röhm, like Mayr, had access to the army political fund and was able to transfer some of the money into the GWP. Drexler wrote to a friend: "An absurd little man has become member No. 7 of our Party."

In February 1920, the German Workers Party published its first programme which became known as the "Twenty-Five Points". It was written by Eckart, Adolf Hitler, Gottfried Feder and Anton Drexler. In the programme the party refused to accept the terms of the Versailles Treaty and called for the reunification of all German people. To reinforce their ideas on nationalism, equal rights were only to be given to German citizens. "Foreigners" and "aliens" would be denied these rights. To appeal to the working class and socialists, the programme included several measures that would redistribute income and war profits, profit-sharing in large industries, nationalization of trusts, increases in old-age pensions and free education. Feder greatly influenced the anti-capitalist aspect of the Nazi programme and insisted on phrases such as the need to "break the interest slavery of international capitalism" and the claim that Germany had become the "slave of the international stock market".

Hitler had more respect for Eckart than other leaders of the GWP. The journalist, Konrad Heiden, pointed out: "The recognized spiritual leader of this small group was Eckart, the journalist and poet, twenty-one years older than Hitler. He had a strong influence on the younger man, probably the strongest anyone ever has had on him. And rightly so. A gifted writer, satirist, orator, even (or so Hitler believed) thinker, Eckart was the same sort of uprooted, agitated, and far from immaculate soul.... He could tell Hitler that he (like Hitler himself) had lodged in flop-houses and slept on park benches because of Jewish machinations which (in his case) had prevented him from becoming a successful playwright." Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) agrees: "He (Eckart) talked well even when he was fuddled with beer, and had a big influence on the younger and still very raw Hitler. He lent him books, corrected his style of expression in speaking and writing, and took him around with him."

Dietrich Eckart decided that the GWP needed its own newspaper. Major Ernst Röhm agreed and together they persuaded his commanding officer, Major General Franz Ritter von Epp to purchase the Völkischer Beobachter (Racial Observer) from the Thule Society for 60,000 marks. The money came from wealthy friends and secret army funds. Eckart became the editor of the paper and used it to publicize the policies of the GWP. Later, Ernst Hanfstaengel provided $1,000 to ensure the daily publication of the newspaper. As William L. Shirer, the author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1964), has pointed out: "It became a daily, thus giving Hitler the prerequisite of all German political parties, a daily newspaper in which to preach the party's gospels."

Hitler's reputation as an orator grew and it soon became clear that he was the main reason why people were joining the party. At one meeting in Hofbräuhaus he attracted an audience of over 2,000 people and several hundred new members were enrolled. This gave Hitler tremendous power within the organization as they knew they could not afford to lose him. One change suggested by Hitler concerned adding "Socialist" to the name of the party. Hitler had always been hostile to socialist ideas, especially those that involved racial or sexual equality. However, socialism was a popular political philosophy in Germany after the First World War. This was reflected in the growth in the German Social Democrat Party (SDP), the largest political party in Germany. Hitler, therefore redefined socialism by placing the word "National" before it. He claimed he was only in favour of equality for those who had "German blood". Jews and other "aliens" would lose their rights of citizenship, and immigration of non-Germans should be brought to an end.

Adolf Hitler advocated that the party should change its name to the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). Hitler, therefore redefined socialism by placing the word "National" before it. He claimed he was only in favour of equality for those who had "German blood". Jews and other "aliens" would lose their rights of citizenship, and immigration of non-Germans should be brought to an end. In April 1920, the German Workers Party became the NSDAP. Hitler became chairman of the new party and Karl Harrer was given the honorary title, Reich Chairman.

Konrad Heiden, a journalist working in Munich, observed the way Hitler gained control of the party: "Success and money finally won for Hitler complete domination over the National Socialist Party. He had grown too powerful for the founders; they - Anton Drexler among them - wanted to limit him and press him to the wall. But it turned out that they were too late. He had the newspaper behind him, the backers, and the growing S.A. At a certain distance he had the Reichswehr behind him too. To break all resistance for good, he left the party for three days, and the trembling members obediently chose him as the first, unlimited chairman, for practical purposes responsible to no one, in place of Anton Drexler, the modest founder, who had to content himself with the post of honorary chairman (July 29, 1921). From that day on, Hitler was the leader of Munich's National Socialist Movement."

Eckart's biographer, Louis L. Snyder, has argued: "By 1923 Eckart's connections in Munich, added to Hitler's oratorical gifts, gave strength and prestige to the fledgling Nazi political movement. Eckart accompanied Hitler at rallies and was at his side in party parades. While Hitler stirred the masses, Eckart wrote panegyrics to his friend. The two were inseparable. Hitler never forgot his early sponsor... Hitler, he said, was his North Star... He spoke emotionally of his fatherly friend, and there were often tears in his eyes when he mentioned Eckart's name."

Dietrich Eckart died of a heart-attack on 26th December, 1923.

On this day in 1887 Sidney Hillman was born in a Lithuanian village in Russia on 23rd March, 1887. When he was fourteen he was sent to a Jewish seminary. He left after a year and became involved in the trade union movement. Hillman took part in the 1905 Russian Revolution and when this failed he fled the country.

Hillman lived in England for two years before emigrating to the United States in 1907. Hillman settled in Chicago where he found work as a fabric cutter. He joined the union and after he successfully led a strike in 1910 he became an agent for the United Garment Workers of America (UGWA).

In 1914 Hillman agreed to become an official of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) in New York. Later that year Hillman was appointed as president of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA). Under Hillman's leadership the ACWA pioneered several important social and economic schemes such as labor banks, unemployment insurance and cooperative housing projects.

In 1936 the American Labor Party (ALP) was formed by left-wing supporters of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. This included Sidney Hillman, Abraham Cahan and David Dubinsky. The ALP put forward a left-wing, non-socialist, program. Its 1937 Declaration of Principles stipulated that there should be a "sufficient planned utilization of the natural economy so that coal, oil, timber, water, and other natural resources that belong to the American people... shall be protected from predatory interests." The following year, ALP member, Vito Marcantonio was elected to Congress where he represented East Harlem's 20th District.

In 1938 John Abt became chief counsel to Sidney Hillman. For the next ten years, Abt was Hillman's main political operative within the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). According to Michael Myerson: "He (Apt) first conceived the notion of political action committees (PACs) and established CIO-PAC (for which he also served as chief counsel) to build organized labor's political influence."

Sidney Hillman was a member of the Socialist Party but impressed by the policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt when governor of New York, became a supporter of the Democratic Party. In 1933 Roosevelt appointed Hillman as a member of his Labor Advisory Board and during the Second World War was associate director of the Office of Production Management. Sidney Hillman died of a heart-attack on 10th July, 1946.

On this day in 1887 Josef Capek was born in Hronov, Bohemia. He was a painter and writer. Čapek published several novels and a play, Land of Many Names. He also produced political cartoons for the Lidove Noviny, a newspaper based in Prague. An opponent of Adolf Hitler, he was arrested after the German invasion of Czechoslovakia. Capek spent the war in a concentration camp and died at Belsen in April, 1945.

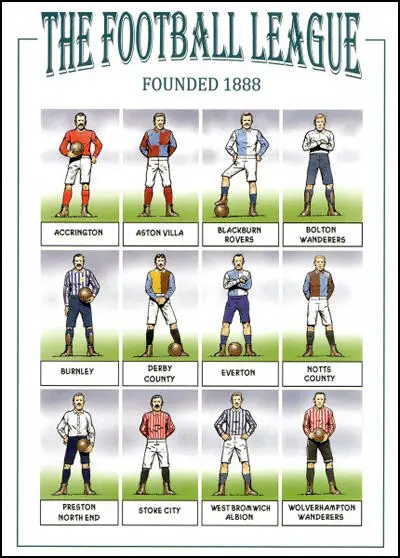

On this day in 1888 the Football League, the world's oldest professional association football league, meets for the first time. In January, 1884, Preston North End played the London side, Upton Park, in the FA Cup. After the game Upton Park complained to the Football Association that Preston was a professional, rather than an amateur team. Major William Sudell, the secretary/manager of Preston North End admitted that his players were being paid but argued that this was common practice and did not breach regulations. However, the FA disagreed and expelled them from the competition.

Sudell had improved the quality of the team by importing top players from other areas. This included several players from Scotland. As well as paying them money for playing for the team, Sudell also found them highly paid work in Preston.

Preston North End now joined forces with other clubs who were paying their players, such as Bolton Wanderers, Aston Villa and Sunderland. In October, 1884, these clubs threatened to form a break-away British Football Association. The Football Association responded by establishing a sub-committee, which included William Sudell, to look into this issue. On 20th July, 1885, the FA announced that it was "in the interests of Association Football, to legalise the employment of professional football players, but only under certain restrictions". Clubs were allowed to pay players provided that they had either been born or had lived for two years within a six-mile radius of the ground.

The decision to pay players increased club's wage bills. It was therefore necessary to arrange more matches that could be played in front of large crowds. On 2nd March, 1888, William McGregorcirculated a letter to Aston Villa, Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Preston North End, and West Bromwich Albion suggesting that "ten or twelve of the most prominent clubs in England combine to arrange home and away fixtures each season."

John J. Bentley of Bolton Wanderers and Tom Mitchell of Blackburn Rovers responded very positively to the suggestion. They suggested that other clubs should be invited to the meeting being held on 23rd March, 1888. This included Accrington, Burnley, Derby County, Notts County, Stoke, Wolverhampton Wanderers, Old Carthusians, and Everton should be invited to the meeting.

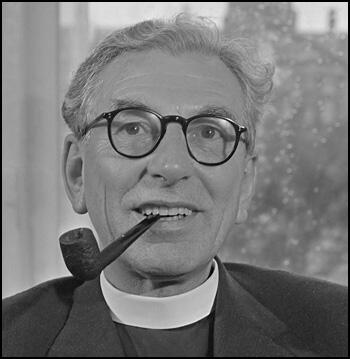

On this day in 1905 John Collins, the youngest of the four children (two daughters and two sons) of Arthur Collins, master builder, and his wife, Hannah Priscilla Edwards, was born at Hawkhurst, Kent, on 23rd March, 1905.

Collins was educated at Cranbrook School, and at Sidney Sussex College. He graduated from the University of Cambridge in 1928. Later that year he was ordained in Canterbury Cathedral and became curate of Whitstable (1928–9).

Collins became interested in the work of Albert Loisy, a French Roman Catholic scholar who had been excommunicated because of his liberal interpretation of the Bible. According to his biographer, Trevor Beeson: "The two men became friends and Collins began to question various elements in his own faith, as well as his conservative approach to politics and the ordering of society."

In 1931 he became an assistant lecturer in theology at King's College. He was dismayed by the impact of the Great Depression on the working class that he became a socialist and joined the Labour Party. He was vice-principal of Westcott House (1934–7) before being appointed in 1938 as dean of Oriel College. On 21st October 1939, he married Diana Clavering Elliot. Over the next few years they had four sons, Andrew, Peter, Mark and Richard.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Collins became a chaplain in the Royal Air Force. According to Trevor Beeson: "He was based at a training station in Wiltshire, where he conceived the idea of forming a fellowship of Christian airmen and airwomen who would meet regularly to study their faith and its practical implications. This experiment aroused considerable interest, though his choice of socialist speakers and his frequent challenges to authority brought him into serious conflict with his senior officers."

In 1946 Collins helped create Christian Action, an organisation dedicated to encouraging people to take their religious convictions into the social and political life of the nation. This included campaigning for the abolition of capital punishment and helping the homeless. In 1948 the prime minister, Clement Attlee, also a Christian Socialist, appointed Collins to a canonry at St Paul's Cathedral so that he might devote more time to the new movement and provide it with a London headquarters.

In 1950 he organized meetings in London and raised money in order to publicize the illegal role of South Africa in the United Nations mandated territory of South-West Africa (Namibia). In 1952 the African National Congress (ANC) under the leadership of Albert Lutuli, began its non-violent campaign against unjust and discriminatory laws in South Africa. Collins and his Christian Action group raised funds to help support the families and dependants of ANC members imprisoned by the South African government. A wealthy Durban businessman invited Collins to visit South Africa in 1954. It was hoped that Collins could be persuaded to end his campaign against the South African government. Collins was disgusted by what he heard and saw in South Africa and this only intensified his campaign against apartheid.

Trevor Huddleston wrote: "I am certain, and am proud to go on record saying it, that informed opposition to apartheid... owes as much to John Collins and Christian Action as informed opposition to the slave trade owed to Wilberforce. And when history comes to be written the name of John Collins will have an equally honoured place. South African racist policy; the anti-apartheid movement; the consequences for world peace of all that happens in the area of race relations anywhere on earth... the fact that today these things are recognized and acknowledged as urgent international priorities is in large measure due to the unflagging dedication and enthusiasm of one man. I thank God for him."

On 2nd November, 1957, the New Statesman published an article by J. B. Priestley entitled Russia, the Atom and the West. In the article Priestley attacked the decision by Aneurin Bevan to abandon his policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament. The article resulted in a large number of people, including Collins, writing letters to the journal supporting Priestley's views.

Kingsley Martin, the editor of the New Statesman, organised a meeting of people inspired by Priestley and as result they formed the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). As well as Priestley, Martin and Collins the group included Bertrand Russell, Fenner Brockway, Vera Brittain, James Cameron, Victor Gollancz, Richard Acland, A. J. P. Taylor and Michael Foot.

As Trevor Beeson pointed out: "The main public manifestation of the campaign's activities was a series of Easter marches to and from the nuclear research establishment at Aldermaston. The numbers taking part ranged from 7,000 to 20,000. Soon, however, there were serious disagreements. A breakaway committee of 100 was formed in 1960 to organize civil disobedience. This caused dissension, indiscipline, and violence in CND and Collins resigned from the chairmanship."

John Collins remained at St Paul's Cathedral until his seventy-sixth birthday and after a brief retirement died in a London hospital on 31st December 1982.

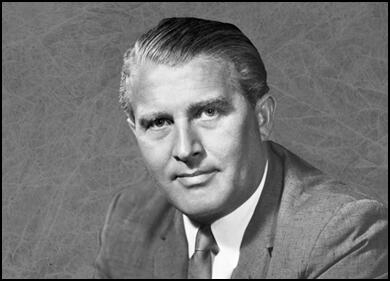

On this day in 1912 Wernher von Braun, the son of a Prussian baron, was born in Wirsitz, Germany in 1912. He studied engineering at Berlin's Charlottenburg Institute of Technology and after reading The Rocket into Interplanetary Space by Hermann Oberth, he became interested in rocket technology and helped form the German Society for Space Travel.

In 1932 Braun's achievements attracted the attentions of Walter Dornberger, who was in charge of the solid-fuel rocket research and development in the Ordnance Department of the German Army. Dornberger recruited Braun and in 1934 he successfully built two rockets that rose vertically for more the than 2.4 kilometres (1.5 miles).

Dornberger was appointed military commander of rocket research station at Peenemunde in 1937. Braun became technical director of the establishment and he began to develop the long-range ballistic missile, the A4 and the supersonic anti-aircraft missile Wasserfall.

During the Second World War Braun began working on a new secret weapon, the V2 Rocket. This 45 feet long, liquid-fuelled rocket carried a one ton warhead, and was capable of supersonic speed and could fly at an altitude of over 50 miles. As a result it could not be effectively stopped once launched.

Heinrich Himmler saw the military potential of Braun's research and took over control of the research station. Himmler became increasingly concerned about the motivation of Braun, considering him more interested in space travel than developing bombs. In March, 1944, Braun was arrested by the Gestapo and was only released when they became convinced that Braun was willing to use all his energies to develop this bomb that Himmler believed had the potential to win the war.

The V2 Rocket was first used in September, 1944. Over 5,000 V-2s were fired on Britain. However, only 1,100 reached their target. These rockets killed 2,724 people and badly injured 6,000. After the D-Day landings, Allied troops were on mainland Europe and they were able to capture the launch sites and by March, 1945, the attacks came to an end.

With the Red Army advancing on the Peenemunde Research Station, Braun and his staff fled west and surrendered to the US Army. Braun and 40 other rocker scientists were taken to the United States where they worked on the development of nuclear missiles.

In 1952 Braun became technical director of the US Army's Ballistic Missile Agency at Huntsville, Alabama and was chiefly responsible for the manufacture and successful launching of Redstone, Jupiter-C, Juno and Pershing missiles.

After the Soviet Union successfully launched Sputnik on 4th October, 1957, Braun concentrated on the development of space rockets and in January, 1958 launched Explorer I.

In 1960 Braun became director of the Marshall Space Flight Center where he developed the Saturn rocket that helped the United States to land on the moon in 1969.

When President Richard Nixon dramatically reduced the space budget in 1972 Braun resigned and became vice-president of Fairchild Industries, an aerospace company

Wernher von Braun, who wrote the books Conquest of the Moon (1953) and Space Frontier (1967) died of cancer at Alexandria on 16th June, 1977.

On this day in 1925 Bessie Rayner Belloc died. Bessie Rayner Parkes, the daughter of the solicitor, Joseph Parkes, was born 16th June. Her grandfather was Joseph Priestley, the scientist and political reformer who was forced to leave the country in 1774. Bessie's father was also a Unitarian with radical political views and was a close friend of reformers such as Henry Brougham and John Stuart Mill.

In 1846 Parkes met Barbara Bodichon, who was running a progressive school in London. The two women became close friends and over the next few years wrote several pamphlets on women's rights, including Remarks on the Education of Girls (1856).

Parkes and Bodichon felt that there was a need for a journal for educated women and in 1858 they founded The Englishwoman's Review. Parkes became editor and over the next few years she made the journal available to writers campaigning for women doctors and the extension of opportunities for women in higher education.

Parkes continued to publish pamphlets and in Essays on Women's Work (1866) she argued that the laws of the country were based on the assumption that women were supported by their husbands or fathers, but with a shortage of men in the country, this was becoming less likely to happen. Parkes therefore suggested that it was necessary to improve the standard of education for girls.

In 1866 Parkes joined with Barbara Bodichon to form the first ever Women's Suffrage Committee. This group organised the women's suffrage petition, which John Stuart Mill presented to the House of Commons on their behalf.

On a visit to France in 1867, Parkes met Louis Belloc. The couple fell in love and decided to marry. Both families objected to the couple getting married. Belloc was younger than Parkes and had been an invalid for thirteen years. Barbara Bodichon also advised against the relationship but the marriage went ahead.

After Louis Belloc died of sunstroke in 1872, Bessie returned to London with her two children. Belloc had abandoned her Unitarian beliefs and was now a member of the Roman Catholic Church. She was also no longer interested in women's rights. Her daughter, the successful novelist, Marie Belloc-Lowndes, showed little interest in the suffrage movement, and her son, Hilaire Belloc, was one of Britain's leading anti-feminists, being opposed to both women having the vote or experiencing higher education.

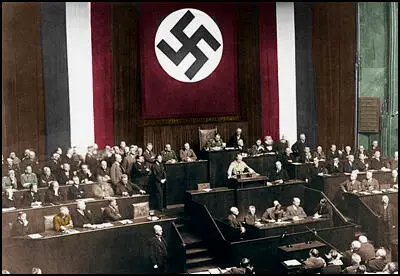

On this day in 1933 Reichstag passes the Enabling Bill. After the 1933 General Election, Chancellor Adolf Hitler proposed an Enabling Bill that would give him dictatorial powers. Such an act needed three-quarters of the members of the Reichstag to vote in its favour. All the active members of the Communist Party, were in prison, in hiding, or had left the country (an estimated 60,000 people left Germany during the first few weeks after the election). This was also true of most of the leaders of the other left-wing party, Social Democrat Party (SDP). However, Hitler still needed the support of the Catholic Centre Party (BVP) to pass this legislation. Hitler therefore offered the BVP a deal: vote for the bill and the Nazi government would guarantee the rights of the Catholic Church. The BVP agreed and when the vote was taken on 24th March, 1933, only 94 members of the SDP voted against the Enabling Bill.

Soon afterwards the Communist Party and the Social Democrat Party became banned organisations. Party activists still in the country were arrested. A month later Hitler announced that the Catholic Centre Party, the Nationalist Party and all other political parties other than the NSDAP were illegal, and by the end of 1933 over 150,000 political prisoners were in concentration camps. Hitler was aware that people have a great fear of the unknown, and if prisoners were released, they were warned that if they told anyone of their experiences they would be sent back to the camp.

It was not only left-wing politicians and trade union activists who were sent to concentration camps. The Gestapo also began arresting beggars, prostitutes, homosexuals, alcoholics and anyone who was incapable of working. Although some inmates were tortured, the only people killed during this period were prisoners who tried to escape and those classed as "incurably insane".

On this day in 1977 David Frost records his first interview with Richard Nixon. A few months earlier Nixon's chief-of staff, Jack Brennan, informed the media that he was willing to give a television interview on his presidency. Nixon was trying to get an agreement for an interview that did not involve a discussion of Watergate. Under these terms, the most he was offered was $400,000. David Frost offered $600,000 (over $2 million in today’s money) and a 20 percent share of any profits, if he was willing to discuss all subjects. Nixon agreed because he considered Frost a lightweight interviewer who would not know enough about the case. This was a miscalculation. Frost recruited James Reston, Jr. and Bob Zelnick to evaluate the Watergate minutiae prior to the interview.

The interviews began on March 23, 1977 and lasted 12 days. Frost lured Nixon into a false sense of security by interviewing Nixon for 24 hours without mentioning Watergate. In these sessions he gave him an easy time and allowed Nixon to boast about his contribution to world peace. However, in the final six hour session, his questioning revealed details of a previously unknown conversation between Nixon and Charles Colson. This clearly unsettled Nixon and Frost was able to go in for the kill. During the interview Nixon suggested that the break-in might have been botched on purpose. He added that he suspected that the CIA had been behind the operation.

The episode on Watergate, broadcast on 4th May, 1977, was watched by 45 million people. A Gallup poll conducted after the interview showed that 69 percent of the public thought that Nixon was still trying to cover up, 72 percent still thought he was guilty of obstruction of justice, and 75 percent thought he deserved no further role in public life.

David Frost was recently asked by Joan Bakewell why he had been willing to take such a dangerous risk by talking on television about Watergate. Frost had been told by Nixon’s chief of staff and confidant, Jack Brennan, that Nixon feared that some of the people who had gone to prison over Watergate, would sue him when they were released. Frost added that this surprisingly did not happen. Maybe Nixon needed the money to stop them from talking. It was not only the burglars who needed “hush money”.