On this day on 8th October

On this day in 1779 English engraver and poet William Blake begins study at the Royal Academy, Old Somerset House, London After marrying Catherine Boucher on 18th August 1782, Blake became a freelance engraver. His main employer was the radical bookseller, Joseph Johnson, who been involved in establishing London's first Unitarian Chapel in 1774.. Johnson introduced Blake to the radical circle of Mary Wollstonecraft, William Godwin, Joseph Priestley and Thomas Paine. Blake began to experiment with a new method of engraving. The first of his illuminated works, Natural Religion, appeared in 1788. This was followed by Songs of Innocence (1789), Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790) and Songs of Experience (1794), a book that deals with topics of corruption and social injustice.

In his books The French Revolution (1791), America: A Prophecy (1793) and Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793), Blake developed his attitude of revolt against authority, combining political belief and visionary ecstasy. Blake feared government persecution and some of work was printed anonymously and was only distributed to political sympathisers. An exhibition of Blake's work at the Royal Academy in 1809 failed to attract any significant interest and he sank into obscurity. Blake continued to produce poetry, paintings and engravings but he rarely found customers for his work. William Blake died in 1827 and was buried in an unmarked grave at Bunhill Fields.

On this day in 1807 Harriet Taylor Mill, the daughter of Thomas Hardy, a London surgeon, and his wife Harriet Hurst, was born in Walworth, on 8th October, 1807. At the age of eighteen she married John Taylor, a wealthy businessman from Islington. In the next few years Harriet had two sons and one daughter, Helen Taylor.

John and Harriet Taylor both became active in the Unitarian Church and developed radical views on politics. They became friendly with William Johnson Fox, a leading Unitarian minister and early supporter of women's rights.

Harriet Taylor moved in radical circles and in 1830 she met the philosopher John Stuart Mill. Taylor was attracted to Mill, the first man she had met who treated her as an intellectual equal. Mill was impressed with Taylor and asked her to read and comment on the latest book he was working on. Over the next few years they exchanged essays on issues such as marriage and women's rights. Those essays that have survived reveal that Taylor held more radical views than Mill on these subjects. She argued: "Public offices being open to them alike, all occupations would be divided between the sexes in their natural arrangements. Fathers would provide for their daughters in the same manner as their sons."

Taylor was attracted to the socialist philosophy that had been promoted by Robert Owen in books such as The Formation of Character (1813) and A New View of Society (1814). In her essays Taylor was especially critical of the degrading effect of women's economic dependence on men. Taylor thought this situation could only be changed by the radical reform of all marriage laws. Although Mill shared Taylor's belief in equal rights, he favoured laws that gave women equality rather than independence.

In 1833 Harriet negotiated a trial separation from her husband. She then spent six weeks with Mill in Paris. On their return Harriet moved to a house at Walton-on-Thames where John Start Mill visited her at weekends. Although Harriet Taylor and Mill claimed they were not having a sexual relationship, their behaviour scandalized their friends. As a result, the couple became socially isolated.

John Roebuck later argued: "My affection for Mill was so warm and so sincere that I was hurt by anything which brought ridicule upon him. I saw, or thought I saw, how mischievous might be this affair, and as we had become in all things like brothers, I determined, most unwisely, to speak to him on the subject. With this resolution I went to the India House next day, and then frankly told him what I thought might result from his connection with Mrs. Taylor. He received my warnings coldly, and after some time I took my leave, little thinking what effect my remonstrances had produced. The next day I again called at the India House. The moment I entered the room I saw that, as far he was concerned, our friendship was at an end. His manner was not merely cold, but repulsive; and I, seeing how matters were, left him. His part of our friendship was rooted out, nay, destroyed, but mine was untouched."

Except for a few articles in the Unitarian journal Monthly Repository, Taylor published little of her own work during her lifetime. However, Taylor read and commented on all the material produced by John Stuart Mill. In his autobiography, Mill claimed that Harriet was the joint author of most of the books and articles that were published under his name. He added, "when two persons have their thoughts and speculations completely in common it is of little consequence in respect of the question of originality, which of them holds the pen."

In 1848 John Stuart Mill's Principles of Political Economy was published. Mill planned to include details of the role that Taylor had played in the production of the book, but when John Taylor heard about this he objected and references to his wife were removed. However, in his autobiography, Mill pointed out that the book was "a joint production with my wife".

John Taylor died of cancer on 3rd May, 1849. Still concerned about gossip and scandal, Harriet insisted that they wait two years before they got married. A few months after the wedding the Westminster Review published The Enfranchisement of Women. Although the article had been mainly written by Taylor, it appeared under John Stuart Mill's name. The same happened with the publication of an article in the Morning Chronicle (28th August, 1851) where they advocated new laws to protect women from violent husbands. A letter written by Mill in 1854 suggests that Harriet was reluctant to be described as joint author of Mill's books and articles. "I shall never be satisfied unless you allow our best book, the book which is to come, to have our two names on the title page. It ought to be so with everything I publish, for the better half of it all is yours".

John Stuart Mill had always favoured the secret ballot but Harriet disagreed and eventually changed her husband's views on the subject. Taylor feared that people would vote in their own self-interest rather than for the good of the community. She believed that if people voted in public, the exposure of their selfishness would shame them in voting for the candidate who put forward policies that were in the interests of the majority.

Harriet Taylor Mill and John Stuart Mill both suffered from tuberculosis. While in Avignon, seeking treatment for this condition in November, 1858, Harriet died. Mill and Taylor had been working on a book The Subjection of Women at the time. Helen Taylor, Harriet's daughter, now helped Mill to finish the book. The two worked closely together for the next fifteen years. In his autobiography Mill wrote that "Whoever, either now or hereafter, may think of me and my work I have done, must never forget that it is the product not of one intellect and conscience but of three, the least considerable of whom, and above all the least original, is the one whose name is attached to it."

On this day in 1821 Emily Blackwell was born in Bristol. Emily's sister, Elizabeth Blackwell, became the first woman in the United States to qualify as a doctor. Emily followed her example and after being rejected by ten medical schools was accepted by the Rush Medical College in Chicago. However, in 1853, when male students complained about having to study with a woman, the Illinois Medical Society vetoed her admission. Soon afterwards Emily managed to get accepted by the Western Reserve University in Cleveland. In 1857 the Blackwell sisters and Marie Zakrzewska established the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. The women gave public lectures on hygiene, created a health centre, appointed sanitary visitors and campaigned for better preventive medicine.

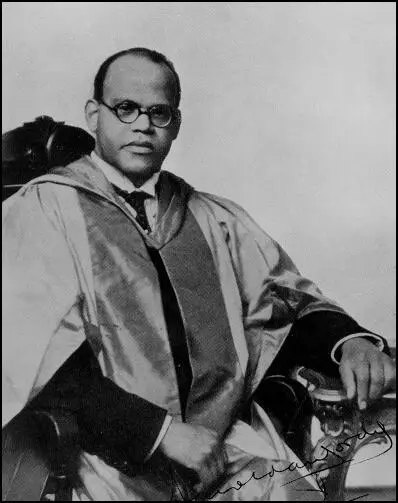

On this day in 1882 Harold Moody was born in Kingston, Jamaica. He moved to London in 1904 to study medicine at King's College. He encountered a great deal of prejudice. As well as finding difficulty finding accommodation, he was refused a post in a hospital because a matron "refused to have a coloured doctor working in the hospital". In February 1913, he started his own medical practice in Peckham. A deeply religious man, Moody was chairman of the Colonial Missionary Society's board of directors and in 1931 president of the London Christian Endeavour Federation. In March 1931 Harold Moody formed the League of Coloured Peoples. Members of the executive included Belfield Clark (Barbados), George Roberts (Trinidad), Samson Morris (Grenada), Robert Adams (British Guiana), and Desmond Buckle (Gold Coast). The League of Coloured Peoples had four main aims: (1) To promote and protect the social, educational, economic and political interests. (2) To interest members in the welfare of coloured peoples in all parts of the world. (3) To improve relations between the races. (4) To cooperate and affiliate with organizations sympathetic to coloured people.

On this day in 1891 Ellen Wilkinson, the daughter of a worker in a textile factory, was born in Manchester. Ellen's parents, Richard Wilkinson and Ellen Wood, were both devout Methodists. She later recalled: "I was utterly bored with religion and sermons... sick of the discussions as to what this or that text meant."

According to Angela Jackson: "Her rebellious tendencies were in evidence even in elementary school and developed alongside a growing moral indignation at the social evils she encountered.... Ellen would accompany him (her father) to lectures on the contemporary debates surrounding evolution, exploring the subject further to reading together.

Ellen was educated at Ardwick School and at the age of eleven won the first of several scholarships. As a result of a series of illnesses, she had been largely educated at home. She later recalled that from this date "I paid for my own education by scholarship until I left university."

In 1906 Ellen won a teaching bursary that meant she could enter the Manchester Day Training College for half a week and she spent the rest of the week teaching at Oswald Road Elementary School.

After a period out of work, Ellen Wilkinson's father became a an insurance clerk. Although her father was a supporter of the Conservative Party, Ellen developed an interest in socialism after reading Merrie England by Robert Blatchford. At the age of sixteen Ellen joined both the Independent Labour Party after hearing a speech made by Kathleen Glasier.

In 1910 Wilkinson became a student at Manchester University where she studied history under Professor George Unwin. Wilkinson was active in the University Socialist Federation where she met Clifford Allen and G.D.H. Cole. Wilkinson became disillusioned with her studies at Manchester and later, when she became involved with the National Council of Labour Colleges, she realised "how little real history" she had been taught at university.

In 1912 became a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and the following year was recruited as a district organizer. Wilkinson also ran the local branch of the Fabian Society where she arranged for people such as Charlotte Despard, Katharine Glasier and Beatrice Webb to speak in Manchester. A pacifist, Wilkinson supported the Non-Conscription Fellowship during the First World War.

There were very few women trade union officials at this time but in July 1915 she was employed by the National Union of Distributive & Allied Workers (AUCE). Wilkinson, the first woman organizer of the AUCE, was also active in local politics and in 1923 was elected to serve on the Manchester City Council.

In the 1924 General Election she was elected to represent Middlesbrough East. In the House of Commons. Wilkinson became known as Red Ellen (both for the colour of her hair and her politics). Active in the 1926 General Strike, afterwards she was co-author with Frank Horrabin and Raymond Postgate of The Workers History of the Great Strike (1927).

Following the 1929 General Election the Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald, appointed Wilkinson as Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Health. Wilkinson opposed the National Government formed by MacDonald and as a result lost her seat in the 1931 General Election. During this period she began an extramarital affair with Frank Horrabin.

Wilkinson became close to Stafford Cripps, the leader of the left-wing of the Labour Party. Other members of this group included Aneurin Bevan, Frank Horrabin, Winifred Batho, Frank Wise, Jennie Lee, Harold Laski, William Mellor, Barbara Betts and G. D. H. Cole. In 1932 the group established the Socialist League.

While out of the House of Commons Wilkinson wrote two books on politics, Peeps at Politicians (1931) and The Terror in Germany (1933) and a novel, The Division Bell Mystery (1932) and contributed articles to the left-wing feminist journal, Time and Tide.

In the 1935 General Election Wilkinson re-entered Parliament as MP for Jarrow. The town had one of the worst unemployment records in Britain. In 1935 nearly 80% of the insured population was out of work. Of the 8,000 skilled manual workers in Jarrow, only 100 were working. In 1936 Wilkinson organised a march of 200 unemployed workers from Jarrow to London where she presented a petition to parliament calling for government action. Wilkinson later wrote an account of the Jarrow Crusade and its outcome called The Town That Was Murdered (1939).

In the 1936 Labour Party Conference, several party members, including Wilkinson, Leah Manning, Stafford Cripps, Aneurin Bevan and Charles Trevelyan, argued that military help should be given to the Spanish Popular Front government, fighting for survival against General Francisco Franco and his right-wing Nationalist Army. Despite a passionate appeal from Senora Isobel de Palencia, the Labour Party supported the Conservative Government's policy of non-intervention.

In December 1936, Ellen Wilkinson and Clement Attlee travelled to Spain where they documented the German bombing of Valencia and Madrid and gave support to the Republican forces fighting against General Francisco Franco. On his arrival back home Attlee sent the British Battalion a message: "I would assure the Brigade of my admiration for their courageous devotion to the cause of freedom and social justice. I shall try to tell the comrades at home of what I have seen. Workers of the World unite." Leah Manning commented "henceforth, the No. 1 Company of the Battalion was known as the Major Attlee Company."

In January 1937 Stafford Cripps and George Strauss decided to launch a radical weekly, The Tribune, to "advocate a vigorous socialism and demand active resistance to Fascism at home and abroad." William Mellor was appointed editor and others such as Wilkinson, Barbara Betts, Aneurin Bevan, Ellen Wilkinson, Harold Laski, Michael Foot, Winifred Batho and Noel Brailsford agreed to write for the paper.

William Mellor wrote in the first issue: "It is capitalism that has caused the world depression. It is capitalism that has created the vast army of the unemployed. It is capitalism that has created the distressed areas... It is capitalism that divides our people into the two nations of rich and poor. Either we must defeat capitalism or we shall be destroyed by it." Stafford Cripps wrote encouragingly after the first issue: "I have read the Tribune, every line of it (including the advertisements!) as objectively as I can and I must congratulate you upon a very first-rate production.''

In May 1937 Wilkinson joined with Charlotte Haldane, Duchess of Atholl, Eleanor Rathbone and J. B. Priestley to establish the Dependents Aid Committee, an organization which raised money for the families of men who were members of the International Brigades.

Wilkinson was a strong advocate of Hire Purchase reform. She was concerned about the large number of working-class people who fell into arrears and then lost the goods that they had partly paid for. In 1937 an average of 600 people a day were having high purchase goods seized. These were then sold to the public, providing companies with extra profits. Wilkinson also objected to the high rates of interest being charged on the goods. In 1938 Wilkinson's High Purchase Act became law. The act required traders to display on the goods the actual cash price plus the sum added for interest, and protected hirers who had paid at least one third of the sum contracted.

In the coalition government formed by Winston Churchill in 1940, Wilkinson was appointed parliamentary secretary to the Minister of Pensions. Later she joined the team led by Herbert Morrison at the Home Office. Wilkinson was made responsible for air raid shelters and was instrumental in the introduction of the Morrison Shelters in 1941.

Following the 1945 General Election, the new Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, appointed Wilkinson as Minister of Education, the first woman in British history to hold the post. Wilkinson's plans to increase the school-leaving age to sixteen had to be abandoned when the government decided that the measure would be too expensive. However, she did managed to persuade Parliament to pass the 1946 School Milk Act that gave free milk to all British schoolchildren.

Ellen Wilkinson, depressed by her failure to bring in all the reforms she believed necessary, took an overdose of barbiturates and died on 6th February, 1947.

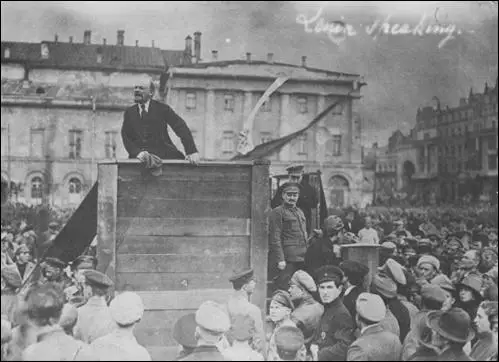

On this day in 1917 Leon Trotsky named chairman of the Petrograd Soviet as Bolsheviks gain control of Russia. Lenin insisted that the Bolsheviks should take action before the elections for the Constituent Assembly. Leon Trotsky supported Lenin's view and urged the overthrow of the Provisional Government. On the evening of 24th October, orders were given for the Bolsheviks to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The Smolny Institute became the headquarters of the revolution and was transformed into a fortress. Trotsky reported that the "chief of the machine-gun company came to tell me that his men were all on the side of the Bolsheviks".

in Petrograd in 1917. By the steps, awaiting his turn to speak, is Leon Trotsky.

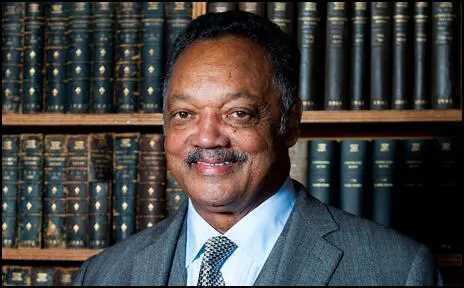

On this day in 1941 Jessie Jackson was born in Greenville, South Carolina. Jackson became active in the civil rights movement while still a student and eventually became a field worker with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). In 1965 he took part in the Selma to Montgomery march and although he was ordained a Baptist minister in 1968, he concentrated on his civil rights work and served as SCLC's national director (1967-71)

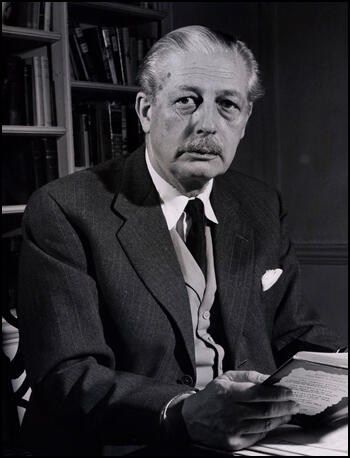

On this day in 1959 Conservatives led by Harold Macmillan won the 1959 General Election by increasing his party's majority from 67 to 107 seats. It has been claimed that the main reason for this success was a growth in working-class income. Richard Lamb argued in The Macmillan Years 1957-1963 (1995) that "The key factor in the Conservative victory was that average real pay for industrial workers had risen since Churchill’s 1951 victory by over 20 per cent".

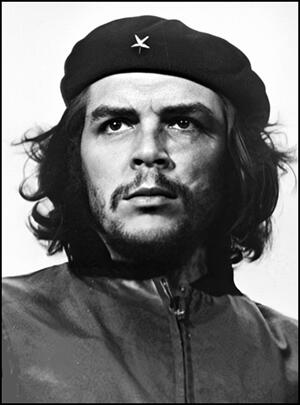

On this day in 1967 Guerrilla leader Che Guevara captured in Bolivia. In 1967 David Morales recruited Félix Rodríguez to train and head a team that would attempt to catch Che Guevara. Guevara was attempting to persuade the tin-miners living in poverty to join his revolutionary army. When Guevara was captured, it was Rodriguez who interrogated him before he ordered his execution in October, 1967. Rodriguez still possesses Guevara’s Rolex watch that he took as a trophy.

On this day in 1967 Clement Attlee died. According to a recent poll of 200 historians he is considered the greatest prime minister in UK history. In 2004, the University of Leeds and Ipsos MORI conducted an online survey of 258 academics who specialised in 20th-century British history and/or politics. There were 139 replies to the survey, a return rate of 54% - by far the most extensive survey done so far on this subject. The respondents were asked, among other historical questions, to rate all the 20th-century prime ministers in terms of their success and asking them to assess the key characteristics of successful PMs. Respondents were asked to indicate on a scale of 0 to 10 how successful or unsuccessful they considered each PM to have been in office (with 0 being highly unsuccessful and 10 highly successful). A mean of the scores could then be calculated and a league table based on the mean scores. The five Labour prime ministers were, on average, judged to have been the most successful, with a mean of 6.0 (median of 5.9). The three Liberal PMs averaged 5.8 (median of 6.2) and the twelve Conservative PMs 4.8 (median of 4.1). Top of the list came Clement Attlee with a score of 8.3.

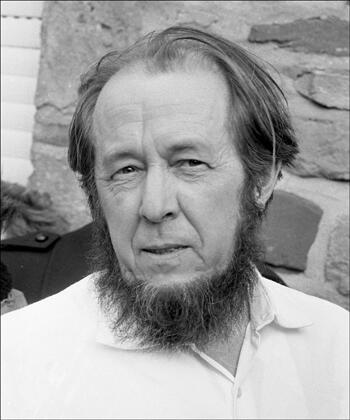

On this day in 1970 Soviet author Alexander Solzhenitsyn wins the Nobel Prize for Literature for his novels The First Circle (1968) and Cancer Ward (1968), based on his experiences as a cancer patient, were both banned after Nikita Khrushchev fell from power. In 1969 Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Soviet Writers' Union. Solzhenitsyn continued to write and his novel, August 1914 (1971) on the First World War, was banned in the Soviet Union but was published abroad. This was followed by his reminiscences, The Gulag Archipelago (1973). This led to his arrest and after being charged with treason, stripped of his citizenship, and was deported from the Soviet Union.