On this day on 4th September

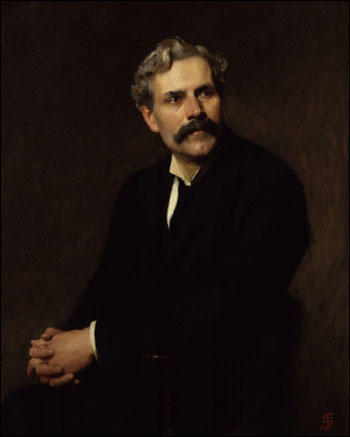

On this day in 1908 Richard Wright, the grandson of slaves, was born in Natchez, Mississippi, on 4th September, 1908. His father deserted the family in 1914 and when Richard was ten years old his mother had a paralytic stroke. The family were extremely poor and after a brief formal education he was forced to seek employment in order to support his mother.

He later wrote: "The bleakness of the future affected my will to study. What had I learned so far that would help me to make a living? Nothing. I could be a porter like my father before me, but what else? And the problem of living as a Negro was cold and hard. What was it that made the hate of whites for blacks so steady, seemingly so woven into the texture of things? What kind of life was possible under that hate? How had that hate come to be? Nothing about the problems of Negroes was ever taught in the classrooms at school; and whenever I would raise these questions with the boys, they would either remain silent or turn the subject into a joke."

Wright worked in a series of menial jobs in Memphis. He wanted to continue his education by using the local library but Jim Crow laws prevented this. Wright solved the problem by forging notes to pretend he was collecting the books for a white man. During this period he was particularly impressed by the work of H. L. Mencken, Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis.

After passing a civil service examination Wright finds work as a post office clerk. After the Wall Street Crash and the beginning of the Depression, Wright lost his job. For a period he found employment with the Negro Burial Society but that came to an end in 1931 and he was forced to go on relief. After several temporary jobs the relief office find him work with the Federal Writers' Project. This enables him to publish his short story, Superstition in the magazine, Abbott's Monthly.

In 1932 Wright began attending meetings of the literary group, the John Reed Club. He later wrote: "The revolutionary words leaped from the page and struck me with tremendous force. My attention was caught by the similarity of the experiences of workers in other lands, by the possibility of uniting scattered but kindred peoples into a whole. It seemed to me that here at last, in the realm of revolutionary expression, Negro experience could find a home, a functioning value and role."

He met several Marxists at the club and later that year joined the American Communist Party. His poems, short-stories and essays are accepted by various left-wing journals including the New Masses, Left Front and International Literature. His poem, Between the World and Me, and a short story, Big Boy Leaves Homes, were both of based on the lynching of a black man that he had witnessed when he was a child.

In May 1937 Wright moved to New York where he became Harlem editor of the Daily Worker and a new literary quarterly, Challenge. The following year, Uncle Tom's Children, a collection of short stories about racism in the United States, was published. In 1940, Bright and Morning Star, was published and Wright announced that all royalties would be used to help to pay the appeal costs of Earl Browder, the general secretary of the American Communist Party, who had been sentenced to four years in prison for misusing a passport.

Wright's novel, Native Son, was accepted by the publishers, Harper, in 1940. The Book of the Month Club selected the novel as its March selection, therefore ensuring large sales and publicity. Over a quarter of a million copies were sold within four weeks, making it the fastest selling Harper novel in twenty years.

Irving Howe argued: "The day Native Son appeared, American culture was changed forever. No matter how much qualifying the book might later need, it made impossible a repetition of the old lies. In all its crudeness, melodrama, and claustrophobia of vision, Richard Wright's novel brought out into the open, as no one ever had before, the hatred, fear, and violence that have crippled and may yet destroy our culture."

Native Son is the story of Bigger Thomas, a black ghetto dweller in Chicago, who is hired by a wealthy family as their chauffeur. He is befriended by the family's liberal daughter and her Communist boyfriend. Thomas accidentally kills the daughter and later he murders his girlfriend after she refuses to help him. He is captured and defended by a Marxist lawyer who tries to get him to articulate the harshness of his life that has led to these violent acts. He is unable to do this and and the end he can only affirm that: "What I killed for, I am!" Some critics attacked the novel for what they believed was an excess of hatred and violence. Marxists also criticised the book for placing too much emphasis on individual rebellion, and not enough on class consciousness and group action.

Wright's next book, Twelve Million Black Voices (1941), was a sociological study of the black migration from the rural South to the urban North. an illustrated folk history of American blacks. Wright deliberately used the word black rather than Negro. Wright argued that the word Negro is a white man's word that artificially limits the scope of a black man's life and helps to set it apart from other Americans.

In the book Richard Wright argues that African civilization is a culture that should inspire pride: "We had our own civilization in Africa before we were captured off to this land. You may smile when we call the way of life we lived in Africa 'civilization', but in numerous respects the culture of many of our tribes was equal to that of the lands from which the slave captors came." The book was hardly reviewed in the United States but received favourable reviews in Europe.

By 1944 Wright felt that the American Communist Party was almost as oppressive as capitalism. He left the party and published an article in the Atlantic Monthly, entitled The God That Failed. He remained a Marxist but as he pointed out in his article, "I wanted to be a communist, but my kind of communist". He added: "I knew in my heart that I should never be able to feel and that simple sharpness about life, should never again express such passionate hope, should never again make so total a commitment of faith."

William Patterson claims that Wright left the party after a dispute with Harry Haywood: "Although he was convinced that the political philosophy of Communism was correct, he did not see a book as a political weapon. He thought that the creative genius of a writer should be freed from all restrictions and restraints, especially those of a political nature, and that the writer should write as he pleased. Unfortunately, Harry Haywood, then top organizer on the Southside, did not exhibit the slightest appreciation that he was dealing with a sensitive, immature creative genius with whom it was necessary to exercise great patience. He criticized some of Wright's earlier characters sharply and tried to force him into a mold that was not to his liking. Name-calling resulted and Haywood used his political position to get a vote of censure against Wright, who thereupon resigned from the Party."

Wright's short novel, The Man Who Lived Underground appeared in 1944. It tells the story of a black man who, after being forced by the police to sign a confession to a crime he had not committed, escapes and hides in a sewer. The book influenced his close friend, Ralph Ellison, in the writing of his novel, the Invisible Man.

Wright's powerful autobiography, Black Boy: A Record of Childhood and Youth was published in 1945. After the Second World War, hostility towards writers with left-wing views increased and in 1947 he moved to Paris. He told a friend, that "any black man remaining in the United States after the age of thirty-five was bound to kill, be killed, or go insane." In Paris he joined a group of black writers and artists that included James Baldwin, Chester Himes and Ollie Harrington.

After a spell of inactivity, Wright published two novels, The Outsider (1953) and Savage Holiday (1954). He also travelled to Ghana and wrote an account of his experiences in the book, Black Power (1954). This was followed by a collection of essays, White Man, Listen (1957). The Psychological Reactions of Oppressed People, provided a warning of what might happen if those in power continued to deny human rights to black people. In another essay, The Literature of the Negro in the United States, Wright promoted the work of Phyllis Wheatley, William Du Bois, Claude McKay and Langston Hughes.

Wright's work inspired a generation of black writers. Eldridge Cleaver wrote in Soul on Ice (1968): "Of all black American novelists, and indeed of all American novelists of any hue, Richard Wright reigns supreme for all profound political, economic, and social reference."

Wright's final novel, The Long Dream was published in 1958. Richard Wright died of a heart attack in Paris on 28th November, 1960. There had been no history of heart trouble and rumours circulated that he had been murdered. Wright was himself concerned about the possibility of being killed since being investigated by Joseph McCarthy in 1953. Just before his death Wright had received several mysterious phone calls from people with fictitious names.

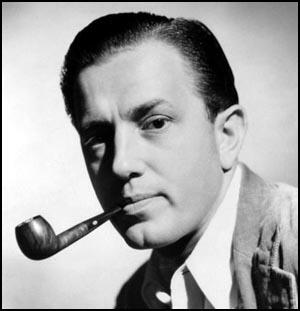

On this day in 1908 Edward Dmytryk was born in British Columbia, Canada. After an education at the California Institute of Technology, he became a messenger boy at Paramount Pictures.

Dmytryk became a film editor in 1929 and directed his first film, The Hawk, in 1935. Over the next eight years he directed 23 films. This included Mystery Sea Raider (1940), Her First Romance (1940), Golden Gloves (1940) Secrets of the Lone Wolf (1941), The Blonde from Singapore (1941), Sweetheart of the Campus (1941), Under Age (1941), The Devil Commands (1941), Counter-Espionage (1942), Confessions of Boston Blackie (1941) and Seven Miles from Alcatraz (1942).

Dmytryk joined the American Communist Party in 1944. He later claimed that the main reason he joined was that he wanted to end world poverty. During this period he was involved in making several politically oriented films such as the anti-fascist Hitler's Children (1943). Murder, My Sweet (1944) was a film where he helped to create the genre later known as "film noir". Crossfire (1947) was one of the first Hollywood movies to tackle anti-Semitism, won four Academy Awards.

After the Second World War the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. In 1947 19 members of the film industry were called to appear before the HUAC. This included Dmytryk, Herbert Biberman, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Dalton Trumbo, Ring Lardner Jr., Samuel Ornitz, John Howard Lawson, Larry Parks, Bertolt Brecht, Richard Collins, Gordon Kahn, Robert Rossen, and Lewis Milestone.

Dmytryk appeared before the HUAC on 29th October, 1947, but like Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Dalton Trumbo, Lester Cole, Ring Lardner Jr., Samuel Ornitz and John Howard Lawson, refused to answer questions about his membership of the Screen Directors Guild or the American Communist Party. Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this.

The chairman of the HUAC, J. Parnell Thomas, refused permission for Dmytryk to make a statement about his political views. This was later published in Hollywood on Trail (1948): "It is my firm belief that democracy lives and thrives only on freedom. This country has always fulfilled its destiny most completely when its people, through their representatives, have allowed themselves the greatest exercise of freedom with the law. The dark period in our history have been those in which our freedoms have been suppressed, to however small a degree. Some of that darkness exists into the present day in the continued suppression of certain minorities."

Edward Dmytryk then went on to argue that he believed that the main reason he was before the HUAC was because he made Crossfire (1947), an attack on anti-Semitism. "In my last few years in Hollywood, I have devoted myself, through pictures such as Crossfire, to a fight against these racial suppressions and prejudices. My work speaks for itself. I believe that it speaks clearly enough so that the people of the country and this Committee, which has no right to inquire into my politics or my thinking, can still judge my thoughts and my beliefs by my work, and by my work alone."

Dmytryk, Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Dalton Trumbo, Lester Cole, Ring Lardner Jr., Samuel Ornitz and John Howard Lawson, were all found guilty of contempt of Congress and given the maximum sentence of a year in prison. The case went before the Supreme Court in April 1950, but with only Justices Hugo Black and William Douglas dissenting, the sentence was confirmed and Dmytryk spent twelve months in Mill Point Federal Prison, West Virginia.

Blacklisted by the Hollywood studios, he moved to England where he directed two films, Obsession (1949) and Give Us This Day (1949). However, Dmytryk had financial problems as a result of divorcing his first wife. Faced with having to sell his plane and encouraged by his new wife, Dmytryk decided to try to get his name removed from the blacklist. Dmytryk's first move was to meet with a journalist, Richard English, who specialized in writing anti-communist articles for the American press. With English's help, Dmytryk wrote What Makes a Hollywood Communist? for the Saturday Evening Post (17th May, 1951). This explained how he now completely rejected his communist past.

On 17th April, 1951, Dmytryk appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee again. This time he answered all their questions including the naming of twenty-six former members of left-wing groups. This included Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Lester Cole, John Howard Lawson, Gordon Kahn, Richard Collins, Jules Dassin, Jack Berry,John Wexley, Michael Gordon, Michael Uris and Bernard Vorhaus. Dmytryk also revealed how Lawson, Scott and Maltz had put him under pressure to make sure his films expressed the views of the American Communist Party. This was particularly damaging as several members of the original Hollywood Ten were at that time involved in court cases with their previous employers.

Dmytryk later recalled: "Not a single person I named hadn't already been named at least a half-dozen times and wasn't already on the blacklist. Because I didn't know that many. I only knew a few people, literally a handful of people, all of whom had been in the Party long before I was, all of whom were known by the FBI and were known to the Committee. There was no question about that. With me it was that defending the Communist Party was something worse than naming the names. I did not want to remain a martyr to something that I absolutely believed was immoral and wrong. It's as simple as that."

Dmytryk then resumed his Hollywood career and after making The Sniper (1952) he directed The Caine Mutiny (1954). Lary May, the author of The Big Tomorrow: Hollywood and the Politics of the American Way (2000) has pointed out: "Edward Dmytryk directed, The Caine Mutiny (1954) to atone for his own communist activities. Significantly the story evoked memories of the Depression-era classic, Mutiny on the Bounty (1935). Where the earlier film justified the revolt of oppressed sailors against injustice, The Caine Mutiny portrayed rebels as an irrational mob of 'immature men'. No doubt this was the reason, explained the producers, that the Navy cooperated in producing a war film that would justify their system."

Other films made by Dmytryk included The Young Lions (1958), Walk on the Wild Side (1962), The Carpetbaggers (1963), Mirage (1965) and The Battle for Anzio (1968). His autobiography, It's a Hell of a Life, was published in 1978. He is also the author of Odd Man Out: A Memoir of the Hollywood Ten.

Edward Dmytryk died in Encino, California, on 1st July, 1999.

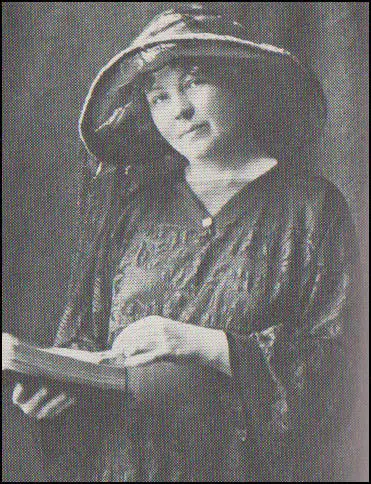

On this day in 1909 Mary Blathwayt writes about Lillian Dove Willcox. "We drove down to Bristol station, and formed up into a procession; it was to receive Mrs. Dove Willcox and Miss Mary Allen, two ex-prisoners and hunger strikers on their return to Bristol. A military band had promised to play, but they declined at the last moment. First came a carriage containing Mrs. Dove Willcox, and Miss Mary Allen; Annie Kenney and some others walked just behind it and then followed a long procession of ladies with banners and tricolour. I helped to carry a banner marked Finland. A very long line of carriages followed. The roads were muddy and it rained a little at first."

Lillian Mary Dove was born in Bedminster in 1875. After the death of her husband in 1908 she joined the Women Social & Political Union in Bristol. On 29th June 1909 she was arrested after taking part in the WSPU deputation to the House of Commons and was sentenced to a month's imprisonment.

While in Holloway Prison Mary Dove Willcox went on hunger-strike. She also assaulted a wardress and was sentenced to a further ten days' imprisonment. Mary Blathwayt recalled what happened when she was released from prison: "We drove down to Bristol station, and formed up into a procession; it was to receive Mrs. Dove Willcox and Miss Mary Allen, two ex-prisoners and hunger strikers on their return to Bristol. A military band had promised to play, but they declined at the last moment. First came a carriage containing Mrs. Dove Willcox, and Miss Mary Allen; Annie Kenney and some others walked just behind it and then followed a long procession of ladies with banners and tricolour."

In 1909 Naylor worked alongside Annie Kenney, Clara Codd, Marie Naylor, Vera Holme and Elsie Howey in the West of England campaign. During this period she became a frequent visitor to Eagle House near Batheaston, the home of fellow WSPU member, Mary Blathwayt. Her father, Colonel Linley Blathwayt was sympathetic to the WSPU cause and on 10th May 1910 he planted a tree, a Picea Orientalis, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house.

Dove Willcox replaced Annie Kenney as secretary of the Bristol branch of the WSPU in 1911. She also employed her home as a place where hunger-strikers, such as Mary Richardson, could recover from their ordeal.

Some leaders of the WSPU such as Sylvia Pankhurst, disagreed with this arson campaign. In 1913, Pankhurst, with the help of Mary Dove Willcox, Keir Hardie, Julia Scurr, Mary Phillips, Millie Lansbury, Eveline Haverfield, Nellie Cressall and George Lansbury, established the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party.

Lillian Dove Willcox, who lived in Ealing, died in 1963.

On this day in 1913 Victor Kiernan one of three children of John Edward Kiernan, was born in Ashton upon Mersey. He was educated at Manchester Grammar School (1924–31) where he won many prizes and scholarships.

In 1931 Kiernan went to Trinity College on a history scholarship. The greatest influence on Kiernan was Maurice Dobb. A lecturer in economics, he was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1922, and was open with his students about his communist beliefs. Kiernan, later reported: "We had no time then to assimilate Marxist theory more than very roughly; it was only beginning to take root in England, although it had one remarkable expounder at Cambridge in Maurice Dobb." Dobb's house, "St Andrews" in Chesterton Lane, was a frequent meeting place for Cambridge communists that it was known locally as "The Red House".

David Guest joined the Communist Party of Great Britain. He became the head of a cell that included Victor Kiernan, John Cornford, Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean and James Klugmann. This enabled dons such as Maurice Dobb and John Bernal to take a back-seat. "The readiness of David Haden-Guest to assume responsibility for the organization had another useful effect. It lifted an unwanted load from the shoulders of Dobb, Bernal and Pascal who, as Fellows of their respective colleges, considered it wiser to remain discreetly in the background. The University authorities adopted a vaguely tolerant view of undergraduate excesses in the political field; but dons who were known to be active Communist officials would have been courting needless trouble." It was claimed that David Guest would "stride into hall at Trinity wearing a hammer and sickle pin in his lapel." With the help of Dave Springhall, Young Communist League national organiser, the party soon had 25 members, Trinity College alone had 12 members and weekly meetings in the students’ rooms.

Victor Kiernan later recalled that Dobb's teaching had helped him to understand the development of society: "We felt, all the same, that it could lift us to a plane far above the Cambridge academic level. We were quite right, as the rapid advance of Marxist ideas and influence since then has demonstrated. Our main concerns, however, were practical ones, popularising socialism and the USSR, fraternising with hunger marchers, denouncing Fascism and the National Government, warning of the approach of war. We belonged to the era of the Third International, genuinely international at least in spirit, whey the Cause stood high above any national or parochial claims."

Victor Kiernan graduated with a double starred first in 1934 and remained at Cambridge University. According to his biographer, Eric Hobsbawm: "His dissertation, published as British Diplomacy in China, 1880–1885 (1939), a diplomatic study with interesting Marxist interpolations, announced his consistent concern with the world outside Europe, not that late nineteenth-century China or any other period or subject satisfied his endless curiosity or exhausted his systematic keeping of records."

In 1938 he used one year of his four-year Trinity College fellowship to visit India. He stayed for the next eight years. Tariq Ali has pointed out: "Kiernan's knowledge of India was first-hand. He was there from 1938-46, establishing contacts and organising study-circles with local Communists and teaching at Aitchison (formerly Chiefs) College, an institution created to educate the Indian nobility along the lines suggested by the late Lord Macaulay. What the students (mostly wooden-headed wastrels) made of Kiernan has never been revealed, but one or two of the better ones did later embrace radical ideas. It would be nice to think that he was responsible: it is hard to imagine who else it could have been. The experience taught him a great deal about imperialism and in a set of stunningly well-written books he wrote a great deal on the origins and development of the American Empire, the Spanish colonisation of South America and on other European empires."

He returned to England in 1946. His outspoken Marxism caused difficulty in him finding a teaching post. "He returned to Trinity, an unreconstructed, but always critical, communist with vast plans for a Marxist work on Shakespeare. His referee denounced his politics when he applied for posts at Oxford and Cambridge universities, but - such was Britain in 1948 - did not mind the charming subversive contaminating the history department at Edinburgh University."

Victor Kiernan joined forces with E. P. Thompson, Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm, Maurice Dobb, A. L. Morton, John Saville, Raphael Samuel, George Rudé, Rodney Hilton, Dorothy Thompson and Edmund Dell to establish the Communist Party Historians' Group. Saville later wrote: "The Historian's Group had a considerable long-term influence upon most of its members. It was an interesting moment in time, this coming together of such a lively assembly of young intellectuals, and their influence upon the analysis of certain periods and subjects of British history was to be far-reaching." (8) He also wrote for the journal Past and Present and New Left Review.

Victor Kiernan left the Communist Party of Great Britain after the Hungarian Uprising. He remained a committed Marxist and published a series of books including The Lords of Human Kind: European Attitudes to the Outside World in the Imperial Age (1969), America: the New Imperialism (1978), The Duel in European History (1988) and Tobacco: a History (1991).

Victor Kiernan died aged 95 on 17th February 2009.

On this day in 1914 The Daily Telegraph report on a speech made by Christabel Pankhurst the

After an absence from England of about two and a half years, spent mainly in Paris, Miss Christabel Pankhurst has returned. Speaking on behalf of the Women's Social and Political Union she said: "We feel the best thing we can do is to try and put the case to others as we women see it ourselves. The people of this country must be made to realise that this is a life and death struggle, and that the success of the Germans would be disastrous for the civilization of the world, let alone for the British Empire. Everything that we women have been fighting for and treasure would disappear in the event of a German victory."

On this day in 1914 C. P. Scott records how David Lloyd George withdrew his decision to resign.

He (Lloyd George), Beauchamp, Morley and Burns had all resigned from the Cabinet on the Saturday before the declaration of war on the ground that they could not agree to Grey's pledge to Cambon (the French ambassador in London) to protect north coast of France against Germans, regarding this as equivalent to war with Germany. On urgent representations of Asquith he (Lloyd George) and Beauchamp agreed on Monday evening to remain in the Cabinet without in the smallest degree, as far as he was concerned, withdrawing his objection to the policy but solely in order to prevent the appearance of disruption in face of a grave national danger. That remains his position. He is, as it were, an unattached member of the Cabinet.

On this day in 1915 Horatio Bottomley, pointed out in the John Bull Magazine that Ramsay MacDonald was keeping a secret from the public. "We have remained silent with regard to certain facts which have been in our possession for a long time. First of all, we knew that this man was living under an adopted name - and that he was registered as James MacDonald Ramsay - and that, therefore, he had obtained admission to the House of Commons in false colours, and was probably liable to heavy penalties to have his election declared void. But to have disclosed this state of things would have imposed upon us a very painful and unsavoury duty. We should have been compelled to produce the man's birth certificate. And that would have revealed what today we are justified in revealing - for the reason we will state in a moment... it would have revealed him as the illegitimate son of a Scotch servant girl!"

In his diary, MacDonald recorded his reaction to the article. "On the day when the paper with the attack was published, I was travelling from Lossiemouth to London in the company as far as Edinburgh with the Dowager Countess De La Warr, Lady Margaret Sackville and their maid... I saw the maid had John Bull in her hand. Sitting in the train, I took it from her and read the disgusting article. From Aberdeen to Edinburgh, I spent hours of the most terrible mental pain.... Never before did I know that I had been registered under the name of Ramsay, and cannot understand it now. From my earliest years my name has been entered upon lists, like the school register, etc. as MacDonald. My mother must have made a simple blunder or the registrar must have made a clerical error."

Ramsay MacDonald received many letters of support, including this one from a long-term opponent to his anti-war activities: "For your villainy and treason you ought to be shot and I would gladly do my country service by shooting you. I hate you and your vile opinions - as much as Bottomley does. But the assault he made on you last week was the meanest, rottenest lowdown dog's dirty action that ever disgraced journalism."