Alexander Parvus

Israel Lazarevich Gelfand (Alexander Helphand) was born in Byerazino (now part of Belarus) on 8th September 1867. The family moved to Odessa where he received a private education. As a young man he became very interested in the revolutionary writings of Alexander Herzen. (1)

Helphand enrolled at the University of Basel, where he studied economics and became a follower of Karl Marx. He moved to Germany where he joined the Social Democratic Party and became a close associate of Rosa Luxemburg. According to her biographer, Paul Frölich: "Helphand... whose lively, productive fantasy, grasp of practical politics, and great activism made him seem a kindred spirit to her." (2)

Helphand's insights into world events came from his knowledge of Marxism and his study of political economy, in which he earned a doctorate from university in 1891. He continued to write about politics in 1895 he "endorsed the tactic of the political mass strike, initially as a means of proletarian self-defence" and later as a "weapon of attack and a method of revolution" through the activities of trade unions and left-wing political parties." (3) In these articles he often criticised the ideas of Eduard Bernstein, whose revisionist views appeared in his anti-Marxist book, Evolutionary Socialism. (4)

Alexander Parvus and Lenin

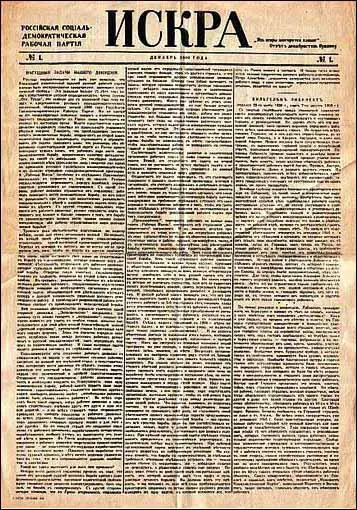

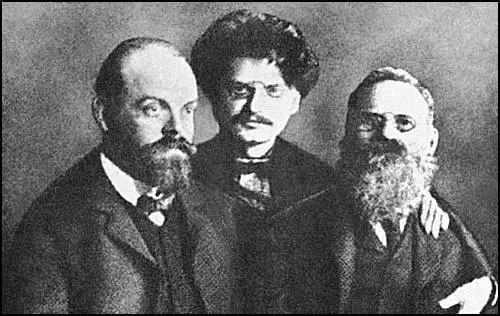

In 1900 he met Lenin and became active in the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP). The party was banned in Russia so most of its leaders were forced to live in exile. Helphand (who adopted the new name of Alexander Parvus) joined forces with Lenin, Julius Martov, George Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Vera Zasulich, Leon Trotsky and Alexander Potresov to establish the newspaper called Iskra (Spark). Its masthead included the words: "Out of this spark will come a conflagration." It was the first underground Marxist paper to be distributed in Russia. It was printed in several European cities and then smuggled into Russia by a network of SDLP agents. (5)

Parvus wrote several articles for the newspaper. Trotsky argued: "Parvus was unquestionably one of the most important of the Marxists at the turn of the century. He used the Marxian methods skilfully, was possessed of wide vision, and kept a keen eye on everything of importance in world events. This, coupled with his fearless thinking and his virile, muscular style, made him a remarkable writer. His early studies brought me closer to the problems of the Social Revolution, and, for me, definitely transformed the conquest of power by the proletariat from an astronomical 'final' goal to a practical task for our own day." (6)

Alexander Parvus began to argue that a revolution must not be considered a far-off event but an imminent possibility. Up until this time Marxists accepted that capitalism would be first overthrown in advanced industrial countries such as Germany and Britain. Parvus began to develop the idea that a revolution could take place during a political crisis in a backward country such as Russia. (7)

At the Second Congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party held in London in 1903, there was a dispute between Lenin and Julius Martov over the future of the SDLP. Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with a large fringe of non-party sympathizers and supporters. Martov disagreed believing it was better to have a large party of activists. Although Martov won the vote 28-23 on the paragraph defining Party membership, with the support of George Plekhanov, Lenin won on almost every other important issue. His greatest victory was over the issue of the size of the Iskra editorial board to three, himself, Plekhanov and Martov. This meant the elimination of Pavel Axelrod, Alexander Potresov and Vera Zasulich - all of whom were "Martov supporters in the growing ideological war between Lenin and Martov". (8)

One of the main arguments was over the subject of democracy in the party. Plekhanov argued in favour of what he and Lenin called the "dictatorship of the proletariat". This meant "the suppression of all social movements which directly or indirectly threaten the interests of the proletariat". When delegates complained about this new development Plekhanov replied by saying that "every democratic principle must be appraised not separately and abstractly, but in its relation to what may be regarded as the basic principle of democracy". The success of the revolution is the supreme law and that might mean the rejection of the idea of "universal suffrage". Lenin applauded when he argued: "If the people, in a surge of revolutionary enthusiasm, should elect a good parliament, we should endeavour to make it a long parliament. If the elections miscarry, we shot try to disperse it, not in two years, but in two weeks." (9)

As Lenin and Plekhanov won most of the votes, their group became known as the Bolsheviks (after bolshinstvo, the Russian word for majority), whereas Martov's group were dubbed Mensheviks (after menshinstvo, meaning minority). Alexander Parvus refused to join either group and developed his own ideas on revolution: "His revolutionary strategy was unique in Russian Marxism. He had no time for the middle classes: his idea was that only the workers could dependably lead the revolutionary struggle against the Romanov monarchy." (10)

Leon Trotsky deeply respected the views of Alexander Parvus and he moved to Munich and stayed with the man he considered to be his political mentor: "My connections with the Bolsheviks had ended with the congress. I broke away from the Mensheviks; I had to act at my own risk. Through a student I got a new passport and, with my wife, who had come abroad again in the autumn of 1904, I took the train to Munich. Parvus put us up in his own house." (11)

Bloody Sunday

1904 was a bad year for Russian workers. Prices of essential goods rose so quickly that real wages declined by 20 per cent. When four members of the Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg, were dismissed at the Putilov Iron Works in December, Father Georgi Gapon tried to intercede for the men who lost their jobs. This included talks with the factory owners and the governor-general of St Petersburg. When this failed, Gapon called for his members in the Putilov Iron Works to come out on strike. (12)

Father Gapon demanded: (i) An 8-hour day and freedom to organize trade unions. (ii) Improved working conditions, free medical aid, higher wages for women workers. (iii) Elections to be held for a constituent assembly by universal, equal and secret suffrage. (iv) Freedom of speech, press, association and religion. (v) An end to the war with Japan. By the 3rd January 1905, all 13,000 workers at Putilov were on strike, the department of police reported to the Minister of the Interior. "Soon the only occupants of the factory were two agents of the secret police". (13)

The strike spread to other factories. By the 8th January over 110,000 workers in St. Petersburg were on strike. Father Gapon wrote that: "St Petersburg seethed with excitement. All the factories, mills and workshops gradually stopped working, till at last not one chimney remained smoking in the great industrial district... Thousands of men and women gathered incessantly before the premises of the branches of the Workmen's Association." (14)

Tsar Nicholas II became concerned about these events and wrote in his diary: "Since yesterday all the factories and workshops in St. Petersburg have been on strike. Troops have been brought in from the surroundings to strengthen the garrison. The workers have conducted themselves calmly hitherto. Their number is estimated at 120,000. At the head of the workers' union some priest - socialist Gapon. Mirsky (the Minister of the Interior) came in the evening with a report of the measures taken." (15)

Gapon drew up a petition that he intended to present a message to Nicholas II: "We workers, our children, our wives and our old, helpless parents have come, Lord, to seek truth and protection from you. We are impoverished and oppressed, unbearable work is imposed on us, we are despised and not recognized as human beings. We are treated as slaves, who must bear their fate and be silent. We have suffered terrible things, but we are pressed ever deeper into the abyss of poverty, ignorance and lack of rights." (16)

The petition contained a series of political and economic demands that "would overcome the ignorance and legal oppression of the Russian people". This included demands for universal and compulsory education, freedom of the press, association and conscience, the liberation of political prisoners, separation of church and state, replacement of indirect taxation by a progressive income tax, equality before the law, the abolition of redemption payments, cheap credit and the transfer of the land to the people. (17)

Over 150,000 people signed the document and on 22nd January, 1905, Father Georgi Gapon led a large procession of workers to the Winter Palace in order to present the petition. The loyal character of the demonstration was stressed by the many church icons and portraits of the Tsar carried by the demonstrators. Alexandra Kollontai was on the march and her biographer, Cathy Porter, has described what took place: "She described the hot sun on the snow that Sunday morning, as she joined hundreds of thousands of workers, dressed in their Sunday best and accompanied by elderly relatives and children. They moved off in respectful silence towards the Winter Palace, and stood in the snow for two hours, holding their banners, icons and portraits of the Tsar, waiting for him to appear." (18)

Harold Williams, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, also watched the Gapon led procession taking place: "I shall never forget that Sunday in January 1905 when, from the outskirts of the city, from the factory regions beyond the Moscow Gate, from the Narva side, from up the river, the workmen came in thousands crowding into the centre to seek from the tsar redress for obscurely felt grievances; how they surged over the snow, a black thronging mass." (19) The soldiers machine-gunned them down and the Cossacks charged them. (20)

The killing of the demonstrators became known as Bloody Sunday and it has been argued that this event signalled the start of the 1905 Revolution. That night the Tsar wrote in his diary: "A painful day. There have been serious disorders in St. Petersburg because workmen wanted to come up to the Winter Palace. Troops had to open fire in several places in the city; there were many killed and wounded. God, how painful and sad." (21)

Permanent Revolution

The day after the massacre all the workers at the capital's electricity stations came out on strike. This was followed by general strikes taking place in Moscow, Vilno, Kovno, Riga, Revel and Kiev. Other strikes broke out all over the country. Pyotr Sviatopolk-Mirsky resigned his post as Minister of the Interior, and on 19th January, 1905, Tsar Nicholas II summoned a group of workers to the Winter Palace and instructed them to elect delegates to his new Shidlovsky-Mirsky Commission, which promised to deal with some of their grievances. (22)

Alexander Parvus and Leon Trotsky were excited by these developments in Russia as they believed it confirmed their ideas on the possibility of revolution taking place in an economically backward country. Parvus wrote: "The events (the strikes following Bloody Sunday) have fully confirmed this analysis. Now no one can deny that the general strike is the most important means of fighting. The twenty-second of January was the first political strike, even if it was disguised under a priest's cloak. One need only add that revolution in Russia may place a democratic workers' government in power." (23)

Parvus and Trotsky began to develop the theory of permanent revolution. that had first been advanced by Karl Marx in The Holy Family (1844). He developed this idea in his Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League (1850). He warned that in any revolution the bourgeois will "want to bring the revolution to an end as quickly as possible... it is our interest and our task to make the revolution permanent until all the more or less propertied classes have been driven from their ruling positions, until the proletariat has conquered state power and until the association of the proletarians has progressed sufficiently far – not only in one country but in all the leading countries of the world – that competition between the proletarians of these countries ceases and at least the decisive forces of production are concentrated in the hands of the workers." (24)

Marx believed that this revolution would take place in an advanced industrial country such as Germany and Britain. Parvus and Trotsky now believed that it could begin in a country like Russia during a period of crisis. In Capitalism and War, published in Iskra, he gave the example of the Russo-Japanese which he believed could be "the bloody dawn of coming great events". (25)

Parvus predicted that imperialist wars would shatter the bases of the existing world order. (26) Parvus went on to argue: "The war began because of Manchuria and Korea, it has already become a battle for hegemony in Eastern Asia, it will extend into the question of the world position of autocratic Russia and will conclude with a transformation of the political balance of the whole world. Its first consequence will be the fall of the Russian autocracy." (27)

The following month he wrote another article for the journal that introduced the idea of permanent revolution. Although he believed that a communist revolution would not succeed in the long-term in Russia because the country lacked a large working-class and the middle-class was too closely tied to the autocracy. The peasants, the over-whelming majority of the population, "were politically unawakened, lacked a class organization and could only contribute to the extension of anarchy". (28)

Alexander Parvus suggested that universal suffrage was an end in itself since the middle class would always find ways to manipulate the electoral system. Therefore the "bureaucracy ad officer corps had to be eliminated". What was needed was just an uprising as demanded by the Bolsheviks but a commitment to a struggle to "make the revolution permanent". (29)

The only way for the revolution to be successful was to spread it to the industrialized countries. This is what Parvus meant by the term permanent revolution. According to the authors of Witnesses to Permanent Revolution: The Documentary Record (2011) Parvus argued that the Social Democratic Labour Party must "prepare for prolonged class struggle and even civil war, in which the historical experience of Europe might be dramatically abbreviated and the Russian proletariat might emerge as the vanguard of international socialist revolution. With an accompanying revolution in Europe, Russia despite its historical backwardness, might even initiate the final goal of building a socialist society." (30)

Rosa Luxemburg supported Parvus in his views on the need for permanent revolution but it was rejected by both Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, who continued to believe in the possibility of achieving communism in one country. (31) Trotsky was greatly influenced by these two articles. According to his biographer, Isaac Deutscher: "Not only were Parvus's international ideas and revolutionary perspective becoming part and parcel of Trotsky's views on Russian history, especially his conceptions of the Russian state, can be traced back to Parvus." (32)

1905 Russian Revolution

On 27th June, 1905, sailors on the Potemkin battleship, protested against the serving of rotten meat infested with maggots. The captain ordered that the ringleaders to be shot. The firing-squad refused to carry out the order and joined with the rest of the crew in throwing the officers overboard. The mutineers killed seven of the Potemkin's eighteen officers, including Captain Evgeny Golikov. They organized a ship's committee of 25 sailors, led by Afanasi Matushenko, to run the battleship. (33)

The Potemkin Mutiny spread to other units in the army and navy. Industrial workers all over Russia withdrew their labour and in October, 1905, the railwaymen went on strike which paralyzed the whole Russian railway network. These events became known as the 1905 Revolution. These industrial disputes developed into a general strike. Leon Trotsky later recalled: "After 10th October 1905, the strike, now with political slogans, spread from Moscow throughout the country. No such general strike had ever been seen anywhere before. In many towns there were clashes with the troops." (34)

Parvus and Trotsky returned to Russia and became involved in the Russian Revolution. This included establishing the St. Petersburg Soviet. On 26th October the first meeting of the Soviet took place in the Technological Institute. It was attended by only forty delegates as most factories in the city had time to elect the representatives. It published a statement that claimed: "In the next few days decisive events will take place in Russia, which will determine for many years the fate of the working class in Russia. We must be fully prepared to cope with these events united through our common Soviet." (35)

Siberia

On 30th October, the Tsar Nicholas II reluctantly agreed to publish details of the proposed reforms that became known as the October Manifesto. This granted freedom of conscience, speech, meeting and association. He also promised that in future people would not be imprisoned without trial. Finally it announced that no law would become operative without the approval of the State Duma. It has been pointed out that Sergei Witte, his Chief Minister, "sold the new policy with all the forcefulness at his command". He also appealed to the owners of the newspapers in Russia to "help me to calm opinions". (36)

These proposals were rejected by the St. Petersburg Soviet: "We are given a constitution, but absolutism remains... The struggling revolutionary proletariat cannot lay down its weapons until the political rights of the Russian people are established on a firm foundation, until a democratic republic is established, the best road for the further progress to Socialism." (37)

On 3rd December, 1905, Parvus and Trotsky were both arrested. They were held in the Kresty Prison before being transferred to the Peter-Paul Fortress. Parvus planned to escape from prison before the start of his trial. Trotsky refused to join him as he wanted to use his trial as a means of communicating his political ideas. Parvus's plot was discovered when guards found some tools in the prison library. (38)

Parvus and his fifty-three comrades were all found guilty and sentenced to three years exile in Siberia. Travelling by horse-drawn sleighs, they took thirty-three days to reach the Obdorsk district, which straddled the Arctic Circle. Parvus escaped and emigrated to Germany, where he published a book about his experiences. Parvus also produced a play written by Maxim Gorky. It ran for over 500 performances but Parvus was accused of not paying Gorky his royalties. After the intervention of Rosa Luxemburg, Parvus paid his debts but his reputation was badly damaged.

The First World War

Parvus moved to Turkey where he developed a close relationship with German ambassador Hans von Wangenheim who had played an important role in persuading its government to join the Central Powers in the First World War. Parvus was attacked by Leon Trotsky and other revolutionaries when he gave his support to Russia's involvement in the First World War and described him as "a political Falstaff is now roaming the Balkans, and he slanders his own deceased double". (39)

In 1915 Hans von Wangenheim sent Parvus to Berlin in March 1915 endorsing his plan that Germany should give support to the Bolsheviks in an attempt to overthrow Tsar Nicholas II. (40) According to one German document Parvus told a representative of the government that "about 20 million roubles would be required to get the Russian revolution completely organized." (41)

Parvus had a meeting with Lenin in Switzerland in May 1915, and arranged the funding of Bolshevik propaganda in Russia. German intelligence set up Parvus' financial network via offshore operations in Copenhagen. Parvus also made sure that he made money out of this relationship with Germany. Helen Rappaport has pointed out Parvus had "grown fat, sexually corrupt and wealthy on business concerns in Turkey and with a penchant for expensive cigars, the opportunistic Helphand (Parvus) had gone over to the German government, operating its an aims contractor and recruiter for the war effort, with an import-export business based in Copenhagen as the front." (42)

Leon Trotsky later commented that "there was always something mad and unreliable about Parvus. In addition to all his other ambitions, this revolutionary was torn by an amazing desire to get rich". (43) Apparently, "he grew rich as a war profiteer, helped, no doubt, by informal commissions he deducted from the huge sums the government paid him to sponsor defeatist and subversive propaganda within the Russia Empire." (44)

Lenin's Sealed Train

On 10th March, 1917, Tsar Nicholas II had decreed the dissolution of the Duma. The High Command of the Russian Army now feared a violent revolution and on 12th March suggested that the Tsar should abdicate in favour of a more popular member of the royal family. Attempts were now made to persuade Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich to accept the throne. He refused and the Tsar recorded in his diary that the situation in "Petrograd is such that now the Ministers of the Duma would be helpless to do anything against the struggles the Social Democratic Party and members of the Workers Committee. My abdication is necessary... The judgement is that in the name of saving Russia and supporting the Army at the front in calmness it is necessary to decide on this step. I agreed." (45)

Prince George Lvov, was appointed the new head of the Provisional Government. One of his first decisions was to allow all political prisoners to return to their homes. Lenin was living in Zurich and he did not hear this news until the 15th March. A group of about twenty Russian exiles arrived at Lenin's home to discuss this important event. Lenin's wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, explained: "From the moment the news of the February revolution came, Ilyich burned with eagerness to go to Russia. England and France would not for the world have allowed the Bolsheviks to pass through to Russia... As there was no legal way it was necessary to travel illegally. But how?" (46)

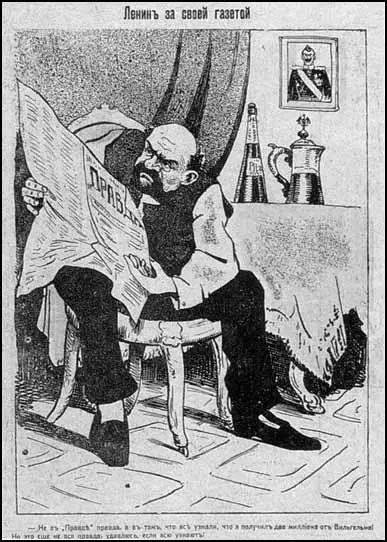

newspaper. The truth - not to be found in Pravda - is that I got two million from

Wilhelm! But even that's not the whole truth. If they knew, I'd hang." (April, 1917)

Aware that the British and French would never allow him a transit visa to Russia through Allied territory in Europe. It was suggested that he should try to return via England under a false passport, but it was decided that this was far too risky and if he was arrested he would be probably interned for the duration of the war. On 19th March 1917 a meeting of socialists was held to discuss the issue. The German socialist Willi Münzenberg was there and later reported that Lenin paced up and down the room declaring, "we must go at all costs". Julius Martov suggested that the best chance would be to send word to the Petrograd Soviet, asking them to offer the Germans repatriation of German prisoners in exchange for the group's safe conduct home via Germany. (47)

The Swiss socialist, Robert Grimm, who Lenin had described as a "detestable centrist", offered to negotiate with the German government in order to obtain a safe passage to Russia. He pointed out that Germany had been spending a great deal of money in producing revolutionary anti-war propaganda in Russia since 1915, in the hope of engineering a withdrawal from the war. This would enable German troops on the Eastern Front to be diverted to the western campaign against Britain and France. Grimm began talks with Count Gisbert von Romberg, the German ambassador in Berne. (48)

Alexander Parvus arrived in Switzerland to carry out negotiations. He made contact with Richard von Kühlmann, a minister at the German Foreign Office. Von Kühlmann sent a message to Army Headquarters explaining the strategy of the German Foreign Office: "The disruption of the Entente and the subsequent creation of political combinations agreeable to us constitute the most important war aim of our diplomacy. Russia appeared to be the weakest link in the enemy chain, the task therefore was gradually to loosen it, and, when possible, to remove it. This was the purpose of the subversive activity we caused to be carried out in Russia behind the front - in the first place promotion of separatist tendencies and support of the Bolsheviks had received a steady flow of funds through various channels and under different labels that they were in a position to be able to build up their main organ, Pravda, to conduct energetic propaganda and appreciably to extend the originally narrow basis of their party." (49)

Parvus also made contact with General Erich Ludendorff who later admitted his involvement in his autobiography, My War Memories, 1914-1918 (1920) that he told senior officials: "Our government, in sending Lenin to Russia, took upon itself a tremendous responsibility. From a military point of view his journey was justified, for it was imperative that Russia should fall." (50)

General Max Hoffmann, chief of the German General Staff on the Eastern Front commented: "We naturally tried, by means of propaganda, to increase the disintegration that the Russian Revolution had introduced into the Army. Some man at home who had connections with the Russian revolutionaries exiled in Switzerland came upon the idea of employing some of them in order to hasten the undermining and poisoning of the morale of the Russian Army."

Hoffmann claims that Reichstag deputy Mathias Erzberger became involved in the negotiations. "And thus it came about that Lenin was conveyed through Germany to Petrograd in the manner that afterwards transpired. In the same way as I send shells into the enemy trenches, as I discharge poison gas at him, I, as an enemy, have the right to employ the expedient of propaganda against his garrisons." (51)

Paul Levi, a close associate of Rosa Luxemburg, and a member of the German anti-war Spartacus League, handled the Berne-Zurich end of negotiations, with Karl Radek. Levi was contacted by the German Ambassador in Switzerland and asked: "How can I get in touch with Lenin? I expect final instructions any moment regarding his transportation". Lenin now negotiated the deal with the ambassador that would allow him to travel through Germany. (52)

In his farewell message to the Swiss workers Lenin explained his analysis of the situation in Russia. "It has fallen to the lot of the Russian proletariat to begin the series of revolutions whose objective necessity was created by the imperialist world war. We know well that the Russian proletariat is less organized and intellectually less prepared for the task than the working class of other countries... Russia is an agricultural country, one of the most backward of Europe. Socialism cannot be established in Russia immediately. But the peasant character of the development of a democratic-capitalist revolution in Russia and make that a prologue to the world-wide Socialist revolution." (53)

Lenin felt he needed the support of other socialists living in Switzerland for his journey through Germany. He sent a telegram to two French anti-war figures living in Switzerland, Romain Rolland and Henri Guilbeaux, asking them to appear in the railroad station on the day of his departure. Rolland refused and sent a message to Guilbeaux: "If you have any influence on Lenin and his friends, dissuade them from going through Germany. They will cause great damage to the pacifist movement and to themselves, for it will then be said that Zimmerwald is a German child." He then went on to quote Anatoli Lunacharsky who had described Lenin as "a dangerous and cynical adventurer". (54)

photograph is Inessa Armand (in the fur-trimmed jacket) and Nadezhda Krupskaya (in large hat).

Lenin insisted that his party of thirty-two should include some twenty non-Bolsheviks, in order to offset the unfavourable impression produced by his trip under German auspices. The people who travelled with him included Gregory Zinoviev, Karl Radek, Inessa Armand, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Georgi Safarov, Zinaida Lilina and Moisey Kharitonov. Lenin's supporters milled around the waiting train carrying revolutionary banners and singing the "Internationale". There was a group of anti-German socialists, shouted, "Spies! German spies! Look how happy they are - going home at the Kaiser's expense!" Anatoli Lunacharsky said that Lenin looked "composed and happy". (55)

Willi Münzenberg was there to see Lenin off on his journey. He later recalled that as the doors closed Lenin leaned from the carriage window, shook his hand and said, "Either we'll be swinging from the gallows in three months or we shall be in power." (56) At the German frontier at Gottmadingen station, they were escorted by German soldiers to their own specially commandeered military sealed train. A locomotive pulled "a green-painted coach comprised of three second-class compartments (mainly for the couples and children) and five third-class compartments, where the single men and women would have to endure the hard wooden seats. The two German officers escorting them took a compartment at the rear." (57)

Once the three of the carriage's four doors at the Russian end were closed shut, Fritz Platten, a Swiss socialist marked them with chalk in German as "sealed". The train was given a high traffic priority by the Germans. Crown Prince Wilhelm, the eldest son of Kaiser Wilhelm II, was delayed for two hours to let Lenin's train to pass. There was a several hours' layover in Berlin during which some members of the German Social Democratic Party boarded the train but were not allowed to communicate with Lenin. (58)

After Germany they travelled through Sweden and Finland. On 2nd April Lenin's family received a telegram: "We arrive Monday at eleven at night. Tell Pravda." Lenin feared being arrested at the Russian border. However, Prince George Lvov, pledge to allow all political prisoners the freedom to return to their homes was kept. At 11.10 at night on 3rd April the train arrived at Finland Station. He was greeted by sailors from the Kronstadt naval base, the Petrograd workers' militia and the Red Guards. (59)

Last Years

On the 4th July, 1917, the Provisional Government published documents that claimed that Alexander Parvus had recruited Lenin as a German agent "commissioned to use every means in his power to undermine the confidence of the Russian people in the Provisional Government" and to agitate for the speediest possible conclusion of a separate peace with Germany. Anti-Bolshevik sentiment spread throughout wide areas of the country and Lenin was forced to go into hiding. (60)

Parvus still retained a loyalty to Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht and refused to help Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party, in dealing with the Spartacus League during the German Revolution. He now retreated to his 32-room mansion on Pfaueninsel, a small island in the River Havel situated near the border with Potsdam and Brandenburg, where he wrote his memoirs.

Alexander Parvus (Alexander Helphand) died on 12th December, 1924.

Primary Sources

(1) Leon Trotsky, My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1971)

Parvus was unquestionably one of the most important of the Marxists at the turn of the century. He used the Marxian methods skilfully, was possessed of wide vision, and kept a keen eye on everything of importance in world events. This, coupled with his fearless thinking and his virile, muscular style, made him a remarkable writer. His early studies brought me closer to the problems of the Social Revolution, and, for me, definitely transformed the conquest of power by the proletariat from an astronomical `final' goal to a practical task for our own day. And yet there was always something mad and unreliable about Parvus. In addition to all his other ambitions, this revolutionary was torn by an amazing desire to get rich. Even this he connected, in those years at least, with his social-revolutionary ideas.

(2) Robert Service, Trotsky (2009)

Trotsky moved to Munich in summer 1904. He hated all the faction ii squabbling and made friends with a lively Marxist emigre based in the Bavarian capital. This was Alexander Helphand, usually known by his pseudonym Parvus. Twelve years older than Trotsky, he had spent sonic years of exile in Archangel province before seeking refuge in Germany and taking a doctorate in philosophy. Quickly he joined the German Social-Democratic Party and helped to mount the attack on the attempts by Eduard Bernstein to move Marxism away from doctrines of revolution and towards those of peaceful political change. Parvus became a famous 'anti-revisionist'. Although he had not lost interest in Russia he disdained to join either the Bolsheviks or the Mensheviks. His revolutionary strategy was unique in Russian Marxism. He had no time for the middle classes: his idea was that only the workers could dependably lead the revolutionary struggle against the Romanov monarchy. Indeed Parvus called for a `workers' government' to be established as soon as Nicolas II was over thrown. Trotsky found all this attractive and Parvus became his intellectual mentor, as the Okhrana noted with some alarm. While Trotsky was immersed in the internal disputes of Menshevism he was helping to divide the party and was inadvertently doing the work of the police. The Okhrani had an interest in encouraging factionalism. By joining up with Parvus, Trotsky was concentrating on questions about how to carry out violent revolution against the Imperial order.

(3) Helen Rappaport, Conspirator: Lenin in Exile (2009)

The Germans had, of course, been well aware, since Lenin's arrest in Galicia in 1914, of his usefulness to them in subverting the Russian war effort and bringing it towards a speedy conclusion. They had been pumping German marks into revolutionary anti-war propaganda in Russia since 1915, in hopes of engineering a defeatist peace in Russia so that their troops on the Eastern Front could be diverted to the deadlocked western campaign against Britain and France. Robert Grimm now approached Count Gisbert von Romberg, the German ambassador in Berne, who was coming under pressure even from the Kaiser himself to accede to the Russians' request for safe conduct through Germany. Lenin's Polish colleague Yakub Hanecki was already in Stockholm raising money for his return, and had been officially appointed as his foreign representative to the Bolshevik Central Committee, when another player and an associate of Hanecki's entered the game. Alexander Helphand, codenamed Parvus, the enigmatic German Social Democrat who had provided Lenin with valuable assistance during Iskra days in Munich, arrived in Switzerland. Now grown fat, sexually corrupt and wealthy on business concerns in Turkey and with a penchant for expensive cigars, the opportunistic Helphand had gone over to the German government, operating its an aims contractor and recruiter for the war effort, with an import-export business based in Copenhagen as the front.

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

The Abdication of Tsar Nicholas II (Answer Commentary)

The Provisional Government (Answer Commentary)

The Kornilov Revolt (Answer Commentary)

The Bolsheviks (Answer Commentary)

The Bolshevik Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject

References

(1) Zbynek Zeman, The Merchant of Revolution: The Life of Alexander Israel Helphand (1965) page 12

(2) Paul Frölich, Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Work (1940) page 12

(3) Richard B. Day and Daniel Gaido, Witnesses to Permanent Revolution: The Documentary Record (2011) page 251

(4) Lionel Kochan, Russia in Revolution (1970) page 147

(5) Adam B. Ulam, The Bolsheviks (1998) page 159

(6) Leon Trotsky, My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1971) page 172

(7) Lionel Kochan, Russia in Revolution (1970) page 148

(8) David Shub, Lenin (1948) page 81

(9) George Plekhanov, Collected Works (1925) page 385

(10) Robert Service, Trotsky (2009) page 80

(11) Leon Trotsky, My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1971) page 172

(12) Victor Serge, Year One of the Russian Revolution (1930) page 43

(13) Lionel Kochan, Russia in Revolution (1970) page 87

(14) Georgi Gapon, The Story of My Life (1905) page 168

(15) Nicholas II, diary entry (21st January, 1917)

(16) Georgi Gapon, petition to Nicholas II (21st January, 1905)

(17) Lionel Kochan, Russia in Revolution (1970) page 90

(18) Cathy Porter, Alexandra Kollontai: A Biography (1980) page 92

(19) Harold Williams, Russia of the Russians (1914) page 19

(20) Victor Serge, Year One of the Russian Revolution (1930) page 43

(21) Nicholas II, diary entry (22nd January, 1905)

(22) Cathy Porter, Alexandra Kollontai: A Biography (1980) page 92

(23) Leon Trotsky, My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1971) page 172

(24) Karl Marx, Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League (March, 1850)

(25) Alexander Parvus, Iskra (10th February, 1904)

(26) Alexander Parvus, Russia and the Revolution (1906) page 83

(27) Alexander Parvus, Iskra (5th March, 1904)

(28) Lionel Kochan, Russia in Revolution (1970) page 148

(29) Robert Service, Trotsky (2009) page 90

(30) Richard B. Day and Daniel Gaido, Witnesses to Permanent Revolution: The Documentary Record (2011) page 255

(31) Paul Frölich, Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Work (1940) page 122

(32) Isaac Deutscher, The Prophet: The Life of Leon Trotsky (2015) page 111

(33) Neal Bascomb, Red Mutiny: Eleven Fateful Days on the Battleship Potemkin (2007) pages 211-212

(34) Leon Trotsky, My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1970) page 180

(35) Statement issued by St. Petersburg Soviet (26th October, 1905)

(36) Lionel Kochan, Russia in Revolution (1970) pages 104-105

(37) Statement from the St. Petersburg Soviet (30th October, 1905)

(38) Robert Service, Trotsky (2009) page 98

(39) Isaac Deutscher, The Prophet: The Life of Leon Trotsky (2015) page 230

(40) Barry Rubin and Wolfgang Schwanitz, Nazis, Islamists, and the Making of the Modern Middle East (2014) page 37

(41) Zbynek Zeman, Germany and the Revolution in Russia: Documents from the Archives of the German Foreign Ministry (1958) page 9

(42) Helen Rappaport, Conspirator: Lenin in Exile (2009) page 265

(43) Leon Trotsky, My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1971) page 172

(44) Adam B. Ulam, Lenin and the Bolsheviks (1965) page 425

(45) Nicholas II, diary entry (15th March, 1917)

(46) Nadezhda Krupskaya, Reminiscences of Lenin (1926) page 286

(47) Helen Rappaport, Conspirator: Lenin in Exile (2009) page 265

(48) Michael Pearson, The Sealed Train Journey to Revolution (1975) page 104

(49) Richard von Kühlmann, telegram to Army Headquarters (December, 1917)

(50) General Erich Ludendorff, My War Memories, 1914-1918 (1920) page 407

(51) General Max Hoffmann, The War of Lost Opportunities (1924) page 174

(52) David Shub, Lenin (1948) pages 211-212

(53) Lenin, statement (6th April, 1917)

(54) Romain Rolland, letter to Henri Guilbeaux (7th April, 1917)

(55) Harrison E. Salisbury, Black Night, White Snow: Russia's Revolutions 1905-1917 (1977) page 406

(56) Sean McMeekin, The Red Millionaire: A Political Biography of Willi Münzenberg (2003) page 45

(57) Helen Rappaport, Conspirator: Lenin in Exile (2009) page 271

(58) Harrison E. Salisbury, Black Night, White Snow: Russia's Revolutions 1905-1917 (1977) page 407

(59) Adam B. Ulam, Lenin and the Bolsheviks (1965) page 429

(60) Lionel Kochan, Russia in Revolution (1970) page 249