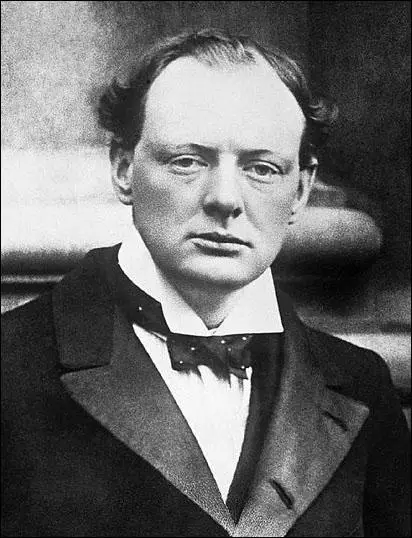

Winston Churchill: 1874-1906

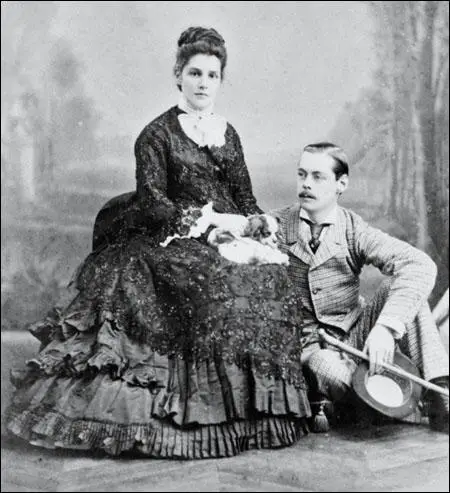

Winston Churchill was born in Blenheim Palace, on 30th November, 1874, just seven and a half months after his parents, Randolph Churchill, a Conservative politician and Jennie Jerome, the daughter of Leonard Jerome, a New York businessman, were married. His father was the third son of the seventh duke and a descendant of John Churchill, first duke of Marlborough. (1)

Clive Ponting, the author of Winston Churchill (1994) has pointed out: "Winston Churchill was born into the small, immensely influential and wealthy circle that still dominated English politics and society. For the whole of his life he remained an aristocrat at heart, deeply devoted to the interests of his family and drawing the majority of his friends and social acquaintances from the elite. From 1876 to 1880 he was brought up surrounded by servants amongst the splendors of the British ascendancy in Ireland." (2)

Churchill's relationship with his parents was typical of upper-class Victorian children. His childhood was largely spent in the nursery and he rarely saw his parents. He was a neglected child, even by the standards of aristocratic families of the time. He later commented: "Solitary trees if they grow at all, grow strong... a boy deprived of a father's care often develops, if he escape the perils of youth, an independence and vigour of thought which may restore in after life the heavy loss of early days." (3)

Churchill later said that he adored his mother, but from afar, "like the Evening Star". His only real emotional support as a boy came from his nanny, Elizabeth Everest. In his autobiography, he claimed "I loved my mother dearly - but at a distance. My nurse was my confidante. Mrs Everest it was who looked after me and tended all my wants. It was to her I poured out all my many troubles, both now in my schooldays. " (4)

Winston Churchill was sent to an expensive preparatory school, St George's at Ascot, just before his eighth birthday in November 1882. This was followed by a period in a boarding school in Brighton. He was considered to be a bright pupil with a phenomenal memory but he took little interest in subjects that did not stimulate him. It was claimed that he was "negligent, slovenly and perpetually late." He was very lonely and wrote to his mother: "I am wondering when you are coming to see me? I hope you are coming to see me soon... You must send someone to see me." (5)

In April 1888 Winston Churchill was sent to Harrow School. He was good in English and History but struggled in Latin and Mathematics. His behaviour remained bad. At the end of his first term his housemaster reported to his mother: "I do not think... that he is in any way wilfully troublesome: but his forgetfulness, carelessness, unpunctuality, and irregularity in every way, have really been so serious... As far as ability goes he ought to be at the top of his form, whereas he is at the bottom. Yet I do not think he is idle; only his energy is fitful, and when he gets to his work it is generally too late for him to do it well." (6)

Randolph Churchill

Randolph Churchill was the Conservative Party MP for Woodstock, where his father, John Spencer Churchill, seventh Duke of Marlborough, was the principal landowner. Churchill's maiden speech in the House of Commons on 22nd May, 1874, was widely praised by leading Conservative Party politicians. Benjamin Disraeli was so impressed that he immediately wrote a letter to Queen Victoria about Churchill's speech: "the House was surprised, and then captivated, by his energy and natural flow and his impressive manner." (7)

Sir Henry Irving, the famous actor, was also taken by this young politician: "Lord Randolph made a profound impression on me. As soon as I realised that he was not posing I said to myself: This is a great man, too; unconsciously he thinks that even Shakespeare needs his approval! He makes himself instinctively the measure of all things and of all men and doesn't trouble himself about the opinions or estimates of others." (8)

Frank Harris was told by Louis John Jennings that in January 1875, Randolph Churchill was diagnosed as suffering from syphilis. He went to see his doctor and explained: "I want you to examine me at once. I got drunk last night and woke up in bed with an appalling old prostitute. Please examine me and apply some disinfectant." The doctor could not find anything wrong with him and it was not until several days later that the first symptoms appeared. "Inwardly I raged that I should have been such a fool. I, who prided myself on my brains, I was going to do such great things in the world, to have caught syphilis!" (9)

Shane Leslie, the son of Jennie's sister Leonie, who said that Randolph's syphilis was contracted from a Blenheim housemaid shortly after Winston's birth. Once the disease was diagnosed, he could no longer sleep with his wife because syphilis was highly contagious and could be passed on to an unborn child. "The treatment of syphilis in those days was primitive, consisting of mercury and potassium iodine, and often ineffective. The disease went through three distinct stages, with periods of remission that made the victim think he was cured. In the second stage, sores appeared on the mouth, the groin became swollen, and there were pimples on the genitals. In the third and fatal stage, the mind became affected." (10)

Randolph Churchill became a friend of the George, Prince of Wales, who was already friendly with his elder brother, George Spencer-Churchill, Marquess of Blandford. In 1875 Churchill criticized the Tory government's financial provision for the prince's visit to India in a letter which Benjamin Disraeli dismissed as an ill-informed Marlborough House manifesto. It is claimed by Roland Quinault this action destroyed Churchill's "rather rising reputation". (11)

While Prince George was in India his companion, Heneage Finch, 7th Earl of Aylesford, decided to divorce his wife and cite the Marquess of Blandford as co-respondent. To prevent a scandal, Randolph Churchill threatened to make public intimate letters which Prince George had written to Lady Aylesford some years before. Aylesford abandoned his divorce proceedings, but the establishment was appalled by what was considered to be an attempt to blackmail the Royal Family. "The Duke of Marlborough was virtually forced to accept the Lord Lieutenancy of Ireland (at a personal cost of £30,000 a year) and take Lord Randolph as his secretary in order to remove him from London society." (12)

On Disraeli's elevation to the House of Lords as Earl of Beaconsfield in 1876, Stafford Northcote became Leader of the Conservative party in the House of Commons. Northcote, who has serious health problems, was an ineffective leader. A group of Tory politicians, including Randolph Churchill, Arthur Balfour, Henry Drummond Wolff and John Eldon Gorst, were especial critical and became known as the "Fourth Party". This group "made a point of treating their leader with public mockery - Lord Randolph had a particularly irritating high pitched laugh which he used with much effect when Northcote spoke - and with private contempt which soon buzzed round the clubs." (13)

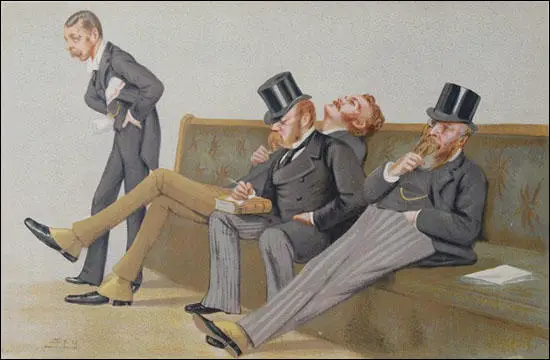

Henry Drummond Wolff and John Eldon Gorst (1st December 1880)

In the 1880 General Election Churchill opposed the repeal of the Union, but also favoured reform of the Irish land tenure laws in the interests of internal peace. Churchill denounced the compensation for disturbance clause in the Relief of Distress Bill proposed by Hugh Law, the Attorney General for Ireland: "It was the tone of vindictive animosity towards landlords which pervaded the speech from the beginning to the end. He should really have been astonished had it been made by the hon. Member for the City of Cork (Mr. Parnell); but, coming as it did from one of the most able and respectable members of the Irish Bar, he was filled with considerable dismay. It occurred to him that if that speech faithfully represented the views of the Government, the Bill was not merely a temporary measure for the relief of Irish distress, but it was something widely different - it was the commencement of a campaign against landlords; it was the first step in a social war; it was an attempt to raise the masses against the propertied classes." (14)

Charles Bradlaugh was a member of the Liberal Party and in the 1880 General Election he won the seat of Northampton. He was also the founder of the National Secular Society, an organisation opposed to Christian dogma. At this time the law required in the courts and oath from all witnesses. Bradlaugh saw this an opportunity to draw attention to the fact that "atheists were held to be incapable of taking a meaningful oath, and were therefore treated as outlaws." (15)

Bradlaugh argued that the 1869 Evidence Amendment Act gave him a right he asked for permission to affirm rather than take the oath of allegiance. The Speaker of the House of Commons refused this request and Bradlaugh was expelled from Parliament. William Gladstone supported Bradlaugh's right to affirm, but as he had upset a lot of people with his views on Christianity, the monarchy and birth control and when the issue was put before Parliament, MPs voted to support the Speaker's decision to expel him. (16)

Bradlaugh now mounted a national campaign in favour of atheists being allowed to sit in the House of Commons. Bradlaugh gained some support from some Nonconformists but he was strongly opposed by the Conservative Party and the leaders of the Anglican and Catholic clergy. When Bradlaugh attempted to take his seat in Parliament in June 1880, he was arrested by the Sergeant-at-Arms and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Bradlaugh received support from Benjamin Disraeli, who warned that Bradlaugh would become a martyr and it was decided to release him. (17)

Randolph Churchill saw this as an opportunity to attack the leaderships of both parties on the subject of Bradlaugh: "In this matter Churchill was motivated not just by partisan opportunism but also by religious belief and parental example. His opposition to Gladstone's 1883 Affirmation Bill recalled his father's opposition to the alteration of the parliamentary oath in 1857. Churchill's denunciation of Bradlaugh's republicanism helped him to restore his credit with the prince of Wales, and he tried to exploit the hostility of the Catholic Irish MPs to Bradlaugh's advocacy of birth control." (18)

26th April, 1881, Charles Bradlaugh was once again refused permission to affirm. William Gladstone promised to bring in legislation to enable Bradlaugh to do this, but this would take time. Bradlaugh was unwilling to wait and when he attempted to take his seat on 2nd August he was once forcibly removed from the House of Commons. Bradlaugh and his supporters organised a national petition and on 7th February, 1882, he presented a list of 241,970 signatures calling for him to be allowed to take his seat. However, when he tried to take the Parliamentary oath, he was once again removed from Parliament. (19)

Stafford Northcote the leader of the Conservative Party in the House of Commons, became very angry about the behaviour of Churchill and attempted to make him toe the official party line. Churchill replied that: "Members who sit below the gangway have always acted in the House of Commons with a very considerable degree of independence of the recognized and constituted chiefs of either party; nor can I (who owe nothing to anyone and depend upon no one) in any way or at any time depart from that well-established and highly respectable tradition." (20)

Churchill argued that Northcote should be replaced by Marquis of Salisbury. He questioned Northcote's leadership qualities and claimed that Salisbury was the only man capable of defeating and replacing William Gladstone. In an anonymous article in The Fortnightly Review, he argued that the leader of the Tory Party should be a member of the House of Lords, where he could influence government policy even when the party was in opposition. However, these constant attacks on Northcote backfired as Tory MPs rallied around to support him. (21)

The opposition of Churchill and the "Fourth Party" to Charles Bradlaugh did not prevent his eventual admission to parliament, but it did lead to the creation on 17th November 1883 of the Primrose League. Its main objectives were: (i) To Uphold and support God, Queen, and Country, and the Conservative cause; (ii) To provide an effective voice to represent the interests of our members and to bring the experience of the Leaders to bear on the conduct of public affairs for the common good; (iii) To encourage and help our members to improve their professional competence as leaders; (iv) To fight for free enterprise. "Churchill was the first member of the league and his mother and wife became prominent members of the ladies' branch. The league quickly became a major force in popular Conservatism and the largest voluntary political organization in late Victorian Britain." (22)

In 1883 Randolph Churchill called for a £10 million reduction in spending to be achieved by cuts in the army and the civil service. (23) During this period he became leader of the "Tory Democracy" movement. He defined this as merely popular support for the monarchy, the House of Lords, and the Church of England - the traditional bulwarks of toryism. Churchill showed little interest in social questions and he did not advocate expensive welfare measures. Churchill took no interest in working-class housing, although it was a fashionable issue at the time. His popularity with the masses owed little to his direct interest in their welfare, but much to the aggressiveness of his platform speeches. His main target was Gladstone who he described as "the greatest living master of the art of personal advertisement". (24)

In May 1885 Churchill helped to orchestrate the defeat of Gladstone's Liberal government on a budget amendment opposing the increase in taxation and the absence of rate relief. Marquis of Salisbury became prime minister; Michael Hicks Beach was chancellor of the exchequer and leader of the House of Commons, while Stafford Northcote - held the largely nominal post of first lord of the Treasury. Churchill became secretary of state for India. The Conservative government was defeated on 26th January 1886. Although he won his seat in the subsequent General Election the Liberal Party returned to power. This caused Churchill financial problems who apparently remarked, "We're out of office, and they're economising on me." (25)

William Gladstone and the Liberals won the election with a majority of seventy-two over the Tories. However, the Irish Nationalists could cause problems because they won 86 seats. On 8th April 1886, Gladstone announced his plan for Irish Home Rule. Mary Gladstone Drew wrote: "The air tingled with excitement and emotion, and when he began his speech we wondered to see that it was really the same familiar face - familiar voice. For 3 hours and a half he spoke - the most quiet earnest pleading, explaining, analysing, showing a mastery of detail and a grip and grasp such as has never been surpassed. Not a sound was heard, not a cough even, only cheers breaking out here and there - a tremendous feat at his age... I think really the scheme goes further than people thought." (26)

The Home Rule Bill said that there should be a separate parliament for Ireland in Dublin and that there would be no Irish MPs in the House of Commons. The Irish Parliament would manage affairs inside Ireland, such as education, transport and agriculture. However, it would not be allowed to have a separate army or navy, nor would it be able to make separate treaties or trade agreements with foreign countries. (27)

Randolph Churchill advised Marquis of Salisbury to defend the Union by forming an alliance with the Spencer Cavendish, Marquess of Hartington and the other Liberals who opposed home rule. Churchill was the first prominent politician to advocate the creation of a "unionist party" - a coalition of Conservatives and unionist Liberals - which would maintain Britain's ties not only with Ireland but also with India and the empire. Churchill also decided to "play the Orange card" - to exploit the strong opposition of Ulster protestants to home rule.In a letter published in The Times, Churchill advocated enlightened unionism, but stated that if the Liberal government ignored the opposition to home rule, then "Ulster will fight, Ulster will be right". (28)

The Conservative Party opposed the measure. So did some members of the Liberal Party, led by Joseph Chamberlain, also disagreed with Gladstone's plan. Chamberlain main objection to Gladstone's Home Rule Bill was that as there would be no Irish MPs at Westminster, Britain and Ireland would drift apart. He added that this would be amounting to the start of the break-up of the British Empire. When a vote was taken, there were 313 MPs in favour, but 343 against. Of those voting against, 93 were Liberals. They became known as Liberal Unionists. (29)

William Gladstone responded to the vote by dissolving parliament rather than resign. During the 1886 General Election he had great difficultly leading a divided party. According to Colin Matthew: "So dedicated was Gladstone to the campaign that he agreed to break the habit of the previous forty years and cease his attempts to convert prostitutes, for fear, for the first time, of causing a scandal (Liberal agents had heard that the Unionists were monitoring Gladstone's nocturnal movements in London with a view to a press exposé)". (30) Churchill made an impassioned attack on Gladstone and his home-rule policy. He claimed that both the British constitution and the Liberal Party were being broken up merely "to gratify the ambition of an old man in a hurry". (31)

In the 1886 General Election the number of Liberal MPs fell from 333 in 1885 to 196, though no party gained an overall majority. William Gladstone resigned on 30th July. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, once again became prime minister. Queen Victoria wrote him a letter where she said she always thought that his Irish policy was bound to fail and "that a period of silence from him on this issue would now be most welcome, as well as his clear patriotic duty." (32)

Salisbury formed a Conservative government and offered Churchill the leadership of the House of Commons. Churchill combined the leadership of the house with the post of chancellor of the exchequer and was thus second only to Salisbury in the ministerial hierarchy. It is claimed that Churchill acted as if he was the leader of the Conservative Party. (33) In a speech at Dartford, he warned Conservatives not to rest on their laurels since "Politics is not a science of the past; politics is a science of the future". He also declared that "The main principle and guiding motive of the Government in the future will be to maintain intact and unimpaired the union of the Unionist party'". (34)

Salisbury acknowledged Churchill's ability, but complained that he had a "wayward and headstrong disposition" and likened the cabinet to "an orchestra in which the first fiddle plays one tune and everybody else, including myself, wishes to play another" (35) When the journalist, Alfred Austin, alleged that Churchill wished to supplant the premier, Salisbury observed that "the qualities for which he is most conspicuous have not usually kept men for any length of time at the head of affairs". (36)

As chancellor of the exchequer Randolph Churchill was determined to be a reformer. His draft budget for 1887 proposed a radical overhaul of the tax system. "Churchill proposed to take 3d. off income tax, lower the duty on tea and tobacco, graduate the house and death duties, and double the government's rate support grant to local authorities. The scheme, though radical, was relatively kind to landowners and not socially redistributive." (37)

Churchill's priority as chancellor was to reduce the defence estimates below those of the last Liberal government. This was opposed by the secretary for war, William Henry Smith. The dispute came to focus on the £500,000 allocated for the fortification of ports and coaling stations. When Smith refused to give way, Churchill wrote to Salisbury, on 20th December 1886, stating his wish to resign from the government since he could not accept the defence estimates and did not expect support from the cabinet. (38) Churchill expected Salisbury to support him in this dispute. He was wrong and Salisbury, in his reply, supported Smith and accepted Churchill's resignation with "profound regret" (39)

Churchill then justified his resignation by linking his desire for economy with wider issues: "I remember the vulnerable and scattered character of the empire, the universality of our commerce, the peaceful tendencies of our democratic electorate, and the hard times, the pressure of competition, and the high taxation now imposed … it is only the sacrifice of a chancellor of the exchequer upon the altar of thrift and economy which can rouse the people to take stock of their lives, their position and their future." (40)

Soldier and Journalist

It has been claimed that Randolph Churchill had a difficult relationship with his son: "As Winston Churchill used to tell his own children, he never had more than five conversations with his father - or not conversations of any length; and he always had the feeling that he didn't quite measure up to expectations. He spent his youth in the certainty, relentlessly rubbed in by Randolph, that he must be less clever than his father. Randolph had been to Eton, whereas it was thought safer to send young Winston to Harrow - partly because of his health (the air of the hill being deemed better for his fragile lungs than the dank air by the Thames) but really because Harrow, in those days, was supposed to be less intellectually demanding." (41)

Winston Churchill started his 16 month course at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst in September, 1893. His father responded by letter to the news that he was a successful student: "I am rather surprised at your tone of exultation over your inclusion in the Sandhurst list. There are two ways of winning an examination, one creditable the other the reverse. You have unfortunately chosen the latter method, and appear to be much pleased with your success." (42)

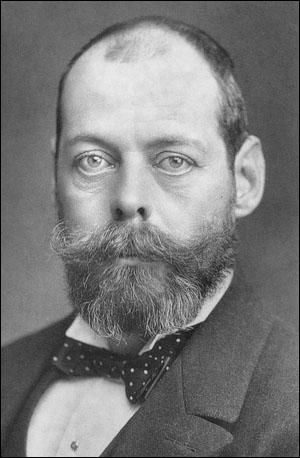

During this period he had to witness the physical and mental decline of his father. He experienced alternating phases of mania and euphoria. He was brought back from holiday in Canada in a straight-jacket. He died at the age of forty-five on 24th January 1895. His neurologist diagnosed his illness as syphilis, though it has recently been argued that his symptoms could have been caused by a tumour on the brain." (43)

Elizabeth Everest, his formal nanny also died that year. When he heard she was very ill, he visited the house she was living in Finsbury Park. Churchill wrote in My Early Life (1930): "Death came very easily to her. She had lived such an innocent and loving life of service to others and held such a simple faith that she had no fears at all, and did not seem to mind very much. She had been my dearest and most intimate friend during the whole of the twenty years I had lived." (44)

Churchill took a train from London to Harrow to tell his younger brother, Jack Churchill, the news, wanting to spare him the anguish of a telegram. Churchill told his mother: "He was awfully shocked, but tried not to show it." He added that he ordered a wreath in his mother's name, as "I thought you would like to send one". He also told her that "I shall never know such a friend again." Churchill organized the funeral making sure the "coffin was covered in wreaths" and later arranged for a headstone to be put on her grave." (45)

Churchill joined the Fourth Hussars in 1895 and he asked his mother to use her influence to get him posted to the Sudan, where Lord Kitchener was mounting a campaign to re-conquer the territory. She was unable to do this but she did manage to persuade General Bindon Blood to arrange for him to see active service on the North-West Frontier with the Malakand Field Service. Churchill welcomed the news with the words: "I have faith in my star - that I am intended to do something in the world." (46)

Winston Churchill took part in the Battle of Omdurman in September, 1898. "Although British forces were outnumbered by more than two to one in facing a collection of 60,000 natives, they had the Maxim gun and their opponents did not. The result was less a battle than wholesale slaughter. The British and Egyptian armies killed about 10,000 and wounded at least another 15,000 and suffered only forty-eight killed and 428 wounded themselves." (47)

Churchill shot and killed at least three of the enemy with his Mauser pistol, was cool and courageous but lucky to survive a bout of hand-to-hand fighting in which 22 British officers and men lost their lives. However, it is estimated that over 30,000 of the enemy were killed. Churchill told his mother he had a "keen desire to kill several of these odious dervishes." He added that "another fifty or sixty casualties would have made our performance historic and made us proud of our race and our blood". (48)

While in the army Churchill supplied military reports for the Daily Telegraph and wrote books such as The Story of the Malakand Field Force (1898) and The River War (1899). According to John Charmley, Churchill became involved in writing as a means of entry into politics: "In this, as in his tireless self-promotion, Churchill showed himself a child of the new political age which dawned after the 1884 Reform Act... The old methods of electioneering would no longer do; it was necessary, if a larger audience was to be reached." (49)

In the spring of 1899 Churchill completed his tour of duty in India, returned home, and resigned his commission. By the time of the outbreak of the South African War, Churchill had negotiated a contract with The Morning Post which made him the highest-paid war correspondent of the day, with a salary of £250 per month with all his expenses paid. A fellow journalist, John Black Atkins, who worked for the Manchester Guardian, commented: "He (Churchill) was slim, slightly reddish-haired, pale, lively.. when the prospects of a career like that of his father, Lord Randolph, excited him, then such a gleam shone from him that he was almost transfigured. I had not before encountered this sort of ambition, unabashed, frankly egotistical, communicating its excitement, and extorting sympathy." (50)

On 15th November, 1899, Churchill volunteered for an early-morning reconnaissance mission on an armoured train, which was a steam engine pulling iron-clad carriages. The Boers blew up the railway line and derailed the engine, before mounting an attack by armed horsemen. The commanding officer was killed and despite his non-combatant status, Churchill took charge of the situation. He tried to get the engine back on the rails and reverse it towards the British camp. After an exchange of fire, he was captured. (51)

Churchill was interned with other British captives in Pretoria. He told a fellow prisoner, Captain Aylmer Haldane, that he was keen to take advantage of his military exploits. He believed that his own heroism during the fight over the train would significantly enhance his chances of getting into Parliament. In an attempt to gain his freedom he wrote to the Boer authorities: "I have consistently adhered to my character as a press representative, taking no part in the defence of the armoured train and being quite unarmed." (52)

Paul Addison, one of his biographers, has pointed out: "Later it was sometimes alleged that Churchill gave his word to his captors that if released he would not take up arms against them, and subsequently broke his parole. As no promise to release him was ever made, this was untrue. But he did persuade Captain Aylmer Haldane and Sergeant-Major Brockie to include him in their escape plan, on the understanding that all three would leave together. In the event Churchill climbed out first and, finding that his fellow escapees were unable to join him, set off on his own. After a series of adventures worthy of John Buchan's hero Richard Hannay he escaped via Portuguese East Africa and arrived in triumph in Durban." (53)

Churchill was portrayed in the British national newspapers as "the heroic Briton who had outwitted the Boers". Over the next six months he reported on a series of military successes. He was later accused of double standards in his reporting. The British used dum-dum bullets against the Boers even though that had been prohibited for use in international warfare by the Hague Convention of 1899. However, when the Boers used them he described them as "illegal" and "improper" and thought they illustrated their "dark and spiteful character", adding that a person who was fully human would not use them. (54)

Churchill accompanied Lord Frederick Roberts on his march through the Orange Free State. He reported on the Battle of Paardeberg (27th February 1900) where Roberts forced the Boer General Piet Cronjé to surrender with some 4,000 men and the capture of the Free State capital Bloemfontein (13th March). Roberts resumed his offensive towards the Transvaal, capturing its capital Pretoria on 31st May. (55)

1900 General Election

In June 1900 Churchill returned to Britain as "a famous figure in every British household with access to a newspaper". He went on a lecture tour of England and the United States amassing the tremendous sum of £10,000. He also wrote about his experiences in the book, London to Ladysmith (1900). A member of the Conservative Party he was selected as the prospective parliamentary candidate for Oldham. (56)

On 25th July, a motion on the Boer War, caused a three way split in the Liberal Party. A total of 40 "Liberal Imperialists" that included Herbert Asquith, Edward Grey, Richard Haldane, and Archibald Primrose, Lord Rosebery, supported the government's policy in South Africa. Henry Campbell-Bannerman and 34 others abstained, whereas 31 Liberals, led by David Lloyd George voted against the motion.

Robert Cecil, the Marquess of Salisbury, decided to take advantage of the divided Liberal Party and on 25th September 1900, he dissolved Parliament and called a general election. Lloyd George, admitted in one speech he was in a minority but it was his duty as a member of the House of Commons to give his constituents honest advice. He went on to make an attack on Tory jingoism. "The man who tries to make the flag an object of a single party is a greater traitor to that flag than the man who fires upon it." (57)

Henry Campbell-Bannerman with a difficult task of holding together the strongly divided Liberal Party and they were unsurprisingly defeated in the 1900 General Election. The Conservative Party won 402 seats against the 183 achieved by Liberal Party. However, anti-war MPs did better than those who defended the war. David Lloyd George increased the size of his majority in Caernarvon Borough. Other anti-war MPs such as Henry Labouchere and John Burns both increased their majorities. In Wales, of ten Liberal candidates hostile to the war, nine were returned, while in Scotland every major critic was victorious. (58)

Churchill became the Tory MP for Oldham, a largely working-class area. He was part of a highly undemocratic political system where the majority of adults could not vote in elections. All women were denied the franchise and about 40 per cent of men were excluded and many others had more than one vote through additional business votes. Churchill defended the system on the grounds that it made "government dignified and easy and the intercourse with foreign states more cordial" and in an act of self-denial wrote, "parliament was elected on a democratic franchise". (59)

Churchill later recalled that he had hoped to enter the House of Commons to join forces with his father but his death destroyed that ambition. "All my dreams of comradeship with him, of entering Parliament at his side and in his support, were ended. There remained for me only to pursue his aims and vindicate his memory." He admitted that he had gone into politics to vindicate Lord Randolph's reputation and to "raise the tattered flag from the stricken battlefield" which his father had let fall. (60)

Churchill gave the impression he was very ambitious and people who met him tended to be very critical of his personality. He came "across as overbearing, wearing people down by his refusal to stop talking about himself or politics, his two real interests in life". Churchill did not seem interested in other people or what they thought and therefore found it difficult to make close personal relationships. The veteran politician, Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke, described him as "about the most ambitious man I had ever met". Henry Cabot Lodge, the American diplomat, wrote to President Theodore Roosevelt about Churchill, saying, "I have met him several times. He is undoubtedly clever but conceited to a degree which it is hard to express either in words or figures." (61)

Robert Lloyd George found him more appealing: "Churchill was unexpectedly short in stature. About five foot six inches tall, he had a pugnacious expression, pale blue eyes and, as a young man, red hair. His head jutted forward in eagerness to enter into debate or battle. His oratory was of a completely different kind to that of Lloyd George; it consisted of sonorous, rhetorical, rolling orotund phrases, learned from his reading of Macaulay and Gibbon and painstakingly prepared and rehearsed until he knew his speeches by heart." (62)

Beatrice Webb was also under whelmed when she met him for the first time: "First impression: restless - almost intolerably so, without capacity for sustained and unexciting labour - egotistical, bumptious, shallow-minded and reactionary, but with a certain personal magnetism, great pluck and some originality - not of intellect but of character. More of the American speculator than the English aristocrat. Talked exclusively about himself and his electioneering plans... But I daresay he has a better side - which the ordinary cheap cynicism of his position and career covers up to a casual dinner acquaintance. Bound to be unpopular - too unpleasant a flavour with his restless, self-regarding personality, and lack of moral or intellectual refinement... His bugbears are Labour, N.U.T. and expenditure on elementary education or on the social services. Defines the higher education as the opportunity for the 'brainy man' to come to the top. No notion of scientific research, philosophy, literature or art: still less of religion. But his pluck, courage, resourcefulness and great tradition may carry him far unless he knocks himself to pieces like his father." (63)

Winston Churchill made few speeches in the House of Commons. He preferred to give lectures where he was paid large sums of money. In 1901 he earned £690 for 14 lectures. When he did speak in Parliament it was usually to attack the government on its spending proposals. It was based on the idea that was employed by his father when he first entered Parliament. It was believed that if a backbencher made life difficult on certain selected issues they would attract attention and encourage the offer of a ministerial post to ensure their silence. (64)

Churchill developed a surprising close friendship with David Lloyd George, one of the most left-wing members of the Liberal Party. Lloyd George told his constituents in 1902: "Last week there was a very interesting speech by a brilliant young Tory member, Mr Winston Churchill. There is no greater admirer of his talent, I assure you, than the individual now addressing you - and many a chat we have had about the situation. We do not always agree, but we do not black each other's eyes." (65)

Free Trade

On 11th July 1902, Arthur Balfour replaced Earl of Rosebery as Prime Minister. Churchill was disappointed when he was not offered a job in the government. Churchill now wrote that what was needed was a "government of the middle - the party which shall be free at once from the sordid selfishness and callousness of Toryism on the one hand and the blind appetites of the Radical masses on the other." (66)

In that year's budget the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Michael Hicks Beach, imposed what he called a small "registration duty" on imported wheat in order to provide extra money to finance war expenditure. Churchill spoke in favour in Parliament, voted for it and defended it in public to his constituents, arguing that a tax on food was justified because "it is the most convenient method of raising the money... and because unless the whole community bear a share in the burden of taxation, what check is there upon expenditure." (67)

On 15th May 1903, Joseph Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary, exploded a political bombshell with a speech in Birmingham advocating a system of preferential colonial tariffs. Herbert Asquith was convinced that Chamberlain had made a serious political mistake and after reading a report of the speech in The Times he told his wife: "Wonderful news today and it is only a question of time when we shall sweep the country". (68) It has been claimed that Chamberlain was undermining the leadership of Arthur Balfour. "A Prime Minister who has not won his own position is always vulnerable, and when the most powerful figure in the Conservative and Unionist alliance chose to challenge one of the fundamental dogmas of British politics, that vulnerability." (69)

Churchill made his opposition to tariff reform clear in a letter to Balfour and said that if he disavowed Chamberlain, he "would command my absolute loyalty", but warned that if tariff reform became party policy "I must reconsider my position in politics". (70) In a speech in the House of Commons he argued: "The idea of giving a preference to the colonies in matters which we must in any case tax for revenue, has now been extended to a definite proposal for the taxation of foodstuffs, and although it is perfectly clear that this proposal of protective duties on food will please agriculturists, or, at any rate, will please the bulk of them, what about the working man?" (71)

On 1st July, 1903, Churchill was one of 53 Conservative MPs who established a Free Food League. However, they were outnumbered by those supporting tariff reform. Churchill was aware that his Oldham constituency was strongly pro-free trade and he began to consider the possibility of leaving the Conservative Party. He wrote to Hugh Cecil: "I am an English Liberal. I hate the Tory party, their men, their words and their methods. I feel no sort of sympathy with them." He added that he considered the Liberal Party as the best refuge "against the twin assaults of capital and labour." (72)

Churchill predicted that "tariff reform" or "protection" would result in a landslide victory for the Liberals at the next election. It would be such a disaster that the "old Conservative Party" would "disappear" and be replaced by a new party that would be "rich, materialist and secular". In a letter to Lord Northcliffe, he complained of "the smug contentment and self-satisfaction of the Government, neither Protectionist nor pro-Boer, which will deal with the shocking administrative inefficiency which prevails". (73)

Churchill became convinced that the Liberal Party would win Oldham at the next general election because of the town's views on free trade. Churchill had several meetings with senior Liberal figures. Churchill told Lord Hugh Cecil that David Lloyd George "spoke to me at length about a positive programme... He said unless we have something to promise as against Mr Chamberlain's promises where are we with the working men? He wants to promise three things which are arranged to deal with three different classes, namely, fixity of tenure to tenant farmers subject to payment of rent and good husbandry: taxation of site values to reduce the rates in the towns: and of course something in the nature of Shackleton's Trade Disputes Bill for the Trade Unionists." (74)

Churchill also had a meeting with Herbert Gladstone, the son of William Gladstone, and the Liberal Party chief whip, about the possibility of switching parties. It was agreed that on 14th February 1904 he would vote with the Liberals on a Free Trade motion in the House of Commons. However, it was not until the 29th March that he told Parliament that he intended joining the Liberals. In protest, all the Conservative Party MPs walked out of the chamber. (75)

Randolph S. Churchill, the author of Winston Churchill (1967) pointed out: "He (Churchill) entered the Chamber of the House of Commons, stood for a moment at the Bar, looked briefly at both the Government and Opposition benches and strode swiftly up the aisle. He bowed to the Speaker and turned sharply to his right to the Liberal benches. He sat down next to Lloyd George in a seat that his father had occupied when in opposition - indeed, the same seat on which Lord Randolph had stood waving his handkerchief to cheer the downfall of Gladstone in 1885." (76)

Churchill argued that David Lloyd George was a major influence on his early political life: "Naturally such a man greatly influenced me. When I crossed the floor of the House and left the Conservative Party in 1904, it was by his side I took my seat." (77) It has been argued that Lloyd George became a father figure to Churchill. John Grigg, Lloyd George's biographer, has claimed that "Churchill soon fell under Lloyd George's spell and for the rest of his life never ceased to regard the Welshman as his master." (78)

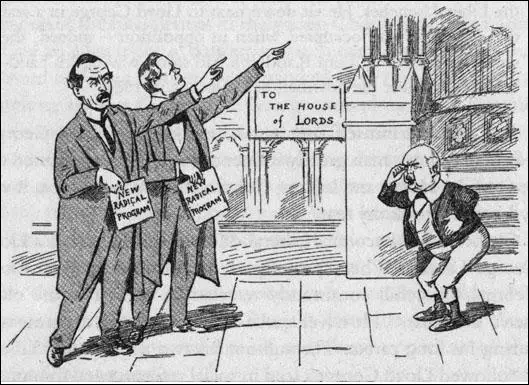

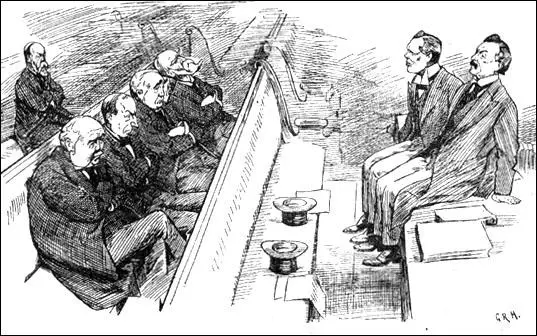

to the House of Lords. Cartoon by George Roland Halkett in The Pall Mall Gazette (22nd October 1904)

Robert Lloyd George has argued that there were political reasons for this relationship. "Churchill looked up to the older man, and sought to his counsel and advice. He wanted to demonstrate his commitment to the Liberal Party by moving towards its more radical wing, which was led by Lloyd George. At this stage Churchill was still, in many ways, the overgrown schoolboy - a genius, certainly, but impetuous, impressionable, grasping the ideas of Liberalism with all the passion of a convert to a new religion, anxious to prove his sincerity and commitment before the older acolytes of the faith." (79)

Lloyd George's devoted secretary and mistress, Frances Stevenson, provides an interesting insight into the relationship. "The plain fact was he (Lloyd George) had not much time for friendship... There was an aloof and withdrawn quality, an essential secretiveness which forbade access to any abiding intimacy... In his relations with Churchill there was a difference... From the earliest political days these two were strangely and prophetically drawn together. Each divined in the other, the quality of genius, which separated them from the ordinary run of men, and drew them together - the village boy and the Duke's grandson." (80)

Violet Bonham Carter argued that "Lloyd George and Churchill had the closest, and in some ways the most incongruous alliance... the most curious and surprising feature of their partnership was that while it exercised no influence whatsoever on Lloyd George, politically or otherwise, it directed, shaped and coloured Winston Churchill's mental attitude and his political course during the next few years. Lloyd George was throughout the dominant partner. His was the only personal leadership I have ever known Winston to accept unquestioningly in his whole political career. He was fascinated by a mind more swift and agile than his own, by its fertility and resource, by its uncanny intuition and gymnastic nimbleness and by a political sophistication which he lacked." (81)

A few days after he left the Conservative Party he admitted to a close friend he might have made a mistake as Arthur Balfour seemed to be turning against the idea of tariff reform: "As the Free Trade issue subsides it leaves my personal ambitions naked and stranded on the beach." (82) Michael Hicks Beach, warned Churchill that "Radical tendencies in a Tory, or Tory tendencies in a Radical, however agreeable to the conscience, handicap a man severely on the run." (83) As the historian, John Charmley, has pointed out: "There is no room in politics for an independent Conservative. Every political Party values loyalty above independence of judgment, but only the Conservatives regard it as the ark of the covenant." (84) Edward VII put it slightly differently: "Churchill is a born cad." (85)

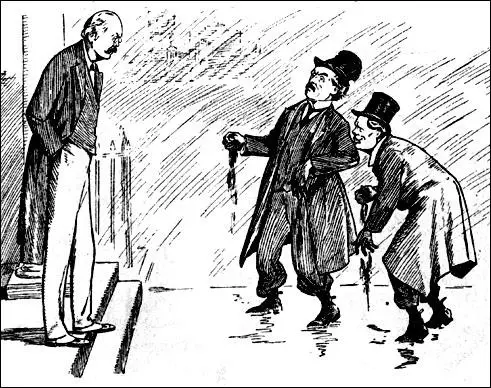

you only waste your time!"

Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George: "Not a bit of it, we're qualifying for high

positions in the next Liberal Government."

Cartoon by George Roland Halkett in The Pall Mall Gazette (18th April, 1905)

Winston Churchill was now selected to stand for the Liberal Party in North West Manchester. Under pressure from the British Brothers' League, the Conservative government introduced an Alien Act, an attempt to reduce immigration to Britain. Balfour claimed that the measure would save money for the country. "Why should we admit into this country people likely to become a public charge? Many countries which exclude immigrants have no Poor Laws they have not those great charities of which we justly boast. The immigrant comes in at his own peril and perishes if he cannot find a living. That is not the case here. From the famous statute of Elizabeth we have taken on ourselves the obligation of supporting every man, woman, and child in this country and saving them from starvation. Is the statute of Elizabeth to have European extension? Are we to be bound to support every man, woman, and child incapable of supporting themselves who choose to come to our shores? That argument seems to me to be preposterous. When it is remembered that some of these persons are a most undesirable element in the population, and are not likely to produce the healthy children... but are afflicted with disease either of mind or of body, which makes them intrinsically undesirable citizens, surely the fact that they are likely to become a public charge is a double reason for keeping them out of the country." (86)

Although the word "Jew" was absent from the legislation, Jews formed the vast bulk of the "aliens" category. Speaking during the committee stage of the Alien Bill, Balfour argued that Jews should be prevented from arriving in Britain because they were not "to the advantage of the civilization of this country... that there should be an immense body of persons who, however patriotic, able and industrious, however much they threw themselves into the national life, they are a people apart and not only had a religion differing from the vast majority of their fellow countrymen but only intermarry amongst themselves." (87)

The Liberal Party did not strongly oppose this proposed measure but Churchill was aware of the significant number of Jews in his constituency. He did not oppose the legislation on moral grounds but that it would be ineffective. "By the admission of the Home Secretary the following case might occur: a ship with 300 immigrants on board arrived at a scheduled port, 285 passed the various tests, and were allowed to land and go forward as trans migrants, while the fifteen who were rejected simply went on to another port in another ship in possession of the same line of steamers, and got in there. He submitted to the Home Secretary that the machinery he was setting up would result in the residuum of immigrants rejected at any one of he specified ports going on to other ports not scheduled, and landing there with perfect impunity." (88)

Arthur Balfour now began to have second thoughts on this policy of Free Trade and warned Joseph Chamberlain about the impact on the electorate in the next general election: "The prejudice against a small tax on food is not the fad of a few imperfectly informed theorists, it is a deep rooted prejudice affecting a large mass of voters, especially the poorest class, which it will be a matter of extreme difficulty to overcome." (89)

Asquith made speeches that attempted to frighten the growing working-class electorate "to whom cheap food had been a much cherished boon for the last quarter of a century and it annoyed the middle class who saw the prospect of a reduction in the purchasing power of their fixed incomes." As well as splitting the Conservative Party it united "the Liberals who had been hitherto hopelessly divided on all the main political issues." (90)

David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill were now seen as the leaders of the left-wing of the Liberal Party. In one cartoon, entitled, "Too Old at Sixty" by George Roland Halkett that was published in The Pall Mall Gazette in 1905, showed Lloyd George and Churchill as "two young firebrands... ready to move on old diehards like Henry Campbell-Bannerman, John Morley, John Burns, Henry Fowler and Victor Bruce. (91)

Churchill: "We've made them take a back seat already, and they'll have to learn to like it."

Cartoon, "Too Old at Sixty" by George Roland Halkett in The Pall Mall Gazette (May, 1905)

In 1905 Winston Churchill concentrated on writing his father's biography. Churchill wrote to most of Lord Randolph's former colleagues in the Conservative Party and asked them for help with the book. Most of them refused as they were still angry by his recent defection to the Liberals. "Churchill chose to represent his father's career as a Greek tragedy. He portrays his father not as a man of ambition but as a man of principle who invented 'Tory Democracy' in the early 1880s... Lord Randolph's resignation is seen as a supreme act of self-sacrifice, undertaken for the cause of public economy and as a result of deep political differences between Lord Randolph and Lord Salisbury rather than personal incompatibility or clashing ambitions." (92)

John Charmley has argued convincingly that the book, Lord Randolph Churchill (1905) "established its author's reputation as an historian, but that was only half its work; the other half was to establish the suitability of its hero as a role-model for his son." (93) Lord Randolph is presented as the true heir of Benjamin Disraeli who had been destroyed by the reactionaries in the Tory Party. Wilfred Scawen Blunt wrote in his diary that Churchill was "playing precisely his father's game" and was now looking "to a leadership of the Liberal Party and an opportunity of full vengeance on those who caused his father's death." (94)

Primary Sources

(1) H. O. D. Davidson, letter to Jennie Churchill (12th July, 1888)

I do not think... that he is in any way wilfully troublesome: but his forgetfulness, carelessness, unpunctuality, and irregularity in every way, have really been so serious... As far as ability goes he ought to be at the top of his form, whereas he is at the bottom. Yet I do not think he is idle; only his energy is fitful, and when he gets to his work it is generally too late for him to do it well.

(2) John Black Atkins met Winston Churchill in 1899, passage from Incidents and Reflections (1947)

He (Churchill) was slim, slightly reddish-haired, pale, lively.. when the prospects of a career like that of his father, Lord Randolph, excited him, then such a gleam shone from him that he was almost transfigured. I had not before encountered this sort of ambition, unabashed, frankly egotistical, communicating its excitement, and extorting sympathy.

(3) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (8th July, 1903)

Went into dinner with Winston Churchill. First impression: restless - almost intolerably so, without capacity for sustained and unexciting labour - egotistical, bumptious, shallow-minded and reactionary, but with a certain personal magnetism, great pluck and some originality - not of intellect but of character. More of the American speculator than the English aristocrat. Talked exclusively about himself and his electioneering plans-wanted me to tell him of someone who would get up statistics for him. "I never do any brainwork that anyone else can do for me" an axiom which shows organising but not thinking capacity. Replete with dodges for winning Oldham against the Labour and Liberal candidates. But I daresay he has a better side - which the ordinary cheap cynicism of his position and career covers up to a casual dinner acquaintance. Bound to be unpopular - too unpleasant a flavour with his restless, self-regarding personality, and lack of moral or intellectual refinement. His political tack is economy: the sort of essence of a moderate; he is at heart a little Englander. Looks to haute finance to keep the peace - for that reason objects to a self-contained Empire as he thinks it would destroy this cosmopolitan capitalism - the cosmopolitan financier being the professional peacemaker of the modern world, and to his mind the acme of civilisation. His bugbears are Labour, N.U.T. and expenditure on elementary education or on the social services. Defines the higher education as the opportunity for the "brainy man" to come to the top. No notion of scientific research, philosophy, literature or art: still less of religion. But his pluck, courage, resourcefulness and great tradition may carry him far unless he knocks himself to pieces like his father.

(4) Winston Churchill, letter to Lord Hugh Cecil (31st December, 1903)

LG (David Lloyd George) spoke to me at length about a positive programme. He said unless we have something to promise as against Mr Chamberlain's promises where are we with the working men? He wants to promise three things which are arranged to deal with three different classes, namely, fixity of tenure to tenant farmers subject to payment of rent and good husbandry: taxation of site values to reduce the rates in the towns: and of course something in the nature of Shackleton's Trade Disputes Bill for the Trade Unionists. Of course with regard to brewers, he would write "no compensation out of public funds". I was very careful not to commit myself on any of these points and I chaffed him as being as big a plunderer as Joe Chamberlain. But entre nous I cannot pretend to have been shocked. Altogether it was a very pleasant and instruc- , five talk and after all LG represents three things:- Wales, English Radicalism and Nonconformists, and they are not three things which politicians can overlook.

(5) Randolph S. Churchill, Winston Churchill: Volume II (1967)

He (Churchill) entered the Chamber of the House of Commons, stood for a moment at the Bar, looked briefly at both the Government and Opposition benches and strode swiftly up the aisle. He bowed to the Speaker and turned sharply to his right to the Liberal benches. He sat down next to Lloyd George in a seat that his father had occupied when in opposition - indeed, the same seat on which Lord Randolph had stood waving his handkerchief to cheer the downfall of Gladstone in 1885.

(6) Violet Bonham Carter, Winston Churchill As I Knew Him (1966)

Lloyd George and Churchill had the closest, and in some ways the most incongruous alliance... the most curious and surprising feature of their partnership was that while it exercised no influence whatsoever on Lloyd George, politically or otherwise, it directed, shaped and coloured Winston Churchill's mental attitude and his political course during the next few years. Lloyd George was throughout the dominant partner. His was the only personal leadership I have ever known Winston to accept unquestioningly in his whole political career. He was fascinated by a mind more swift and agile than his own, by its fertility and resource, by its uncanny intuition and gymnastic nimbleness and by a political sophistication which he lacked.