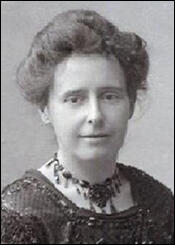

Kate Harvey

Felicia Catherine (Kate) Glanvill was born on 30th November 1862 in Peckham, London. She was the eldest daughter of Frederick Henry William Glanvill (1843-1879), a "Solicitor Clerk" and Felicia Catherine La Thangue (1842-1870), the daughter of an army officer. The union of Frederick and Felicia Glanvill produced two other daughters Edith Mary (born 1866) and Florence Gertrude (born 1869). Kate's mother died in May 1870 when she was 7 years of age. Her father died on 10th April 1879, when she was 16. Her father's personal estate was worth less than £200 when he died. (1)

At the age of 18 Kate was employed as a "Teacher of English" at Granville College for Ladies in Sevenoaks, Kent. (2) She became engaged to Frank Harvey, a Scottish-born (5th May 1854, Renfrewshire) Cotton Merchant. The couple were married on 12th November 1890, at Cuddapah, Madras, India. This union produced 4 children - Marjorie (born 1891 - died 1972), Phyllis (born 1898 - died 1922), and twins Rita (born 1902 - died 1988) and Rex (born 1902 - died 1906). (3)

In 1901 Kate and Frank Harvey were living at a house in Normanton Road, Croydon, Surrey. The family employed at least five servants - a governess, a parlour maid, a kitchen maid, cook, housemaid. (4) Frank Harvey died on 19th September 1905, leaving effects valued at £21,609 12s 6d. (5) According to Helena Wojtczak, after the death of her husband she moved to Kent and "took in and raised disabled children at her Kent home and practised as an unqualified physiotherapist." (6)

Women's Freedom League

In 1907 Charlotte Despard, Teresa Billington-Greig, Edith How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Emma Sproson, Margaret Nevinson, Henria Williams, Violet Tillard and seventy other members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Most of its members were socialists who wanted to work closely with the Labour Party who "regarded it as hypocritical for a movement for women's democracy to deny democracy to its own members." (7)

Kate Harvey joined the WFL. Like the WSPU, the WFL was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. (8)

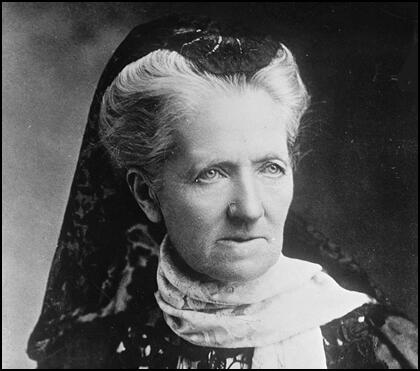

Harvey became close to Charlotte Despard, the leader of the Women's Freedom League. Despard first meet Kate Harvey on 12th January and later characterised the date as "the anniversary of our love". Despard had been active in left-wing groups such as the Social Democratic Federation and the Independent Labour Party for many years and she introduced Harvey to important political figures such as James Keir Hardie and George Lansbury. (9)

Harvey was appointed as the WFL press officer and organiser of The Vote newspaper. Margaret Mulvihill points out that "Harvey was an extremely efficient and courageous woman... and a heroine in the passive resistance campaigns... Her devotion to the Cause was largely motivated by her concern with the welfare of children" and quotes her as saying "the Cause that is nearest to our hearts, the Cause of women - and children, they are inseparable." (10)

Women's Tax Resistance League

In 1909 the Women's Freedom League (WFL) established the Women's Tax Resistance League (WTRL). Octavia Lewin was the first member to take part in the campaign. It was reported in The Daily Chronicle that the "First Passive' Resister", was was to be taken to court. It was announced in the same report that "the Women's Freedom League intends to organise a big passive resistance movement as a weapon in the fight for the franchise." (11)

Harvey first became a tax resister in 1911. The The Vote reported a meeting held at her house, Brackenhill, in Bromley, that was chaired by Laurence Housman, who explained the history of the movement. "Mrs. Harvey... gave a most successful drawing-room meeting to a new and appreciate audience. Mrs Harvey, who is a loyal supporter of Tax Resistance and had a quantity of her household silver sold in June last, took this opportunity of placing before her friends and neighbours the many reasons which led her to take this action." (12)

Kate Harvey became a tax resister by refused to pay insurance tax on behalf of her gardener. The case received a great deal of attention as the gardener was called Asquith - which also happened to be the name of the Prime Minister Henry Herbert Asquith. A year later she was still refused to pay, declaring "I would rather die first". She set about building better barricades. This time the bailiffs needed battering rams to get in. (13)

Votes for Women reported: "Mrs Harvey's is a Tax Resister and for eight months her house, Brackenhill, Highland Road, Bromley, Kent, has been in a state of siege, the doors being chained and padlocked, while numerous bills until women were politically enfranchised. After filing a chain bound round the garden gate, and three men went to the back door, forced the lock, and gained admittance. In the presence of Mrs Harvey's secretary and servants, a distraint was levied on the dinning-room furniture. Mrs Harvey herself was absent when this action was taken." (14)

Harvey was sentenced of two months imprisonment. As a result meetings were held every Monday and Wednesday night in the Market Square, Bromley, by the Women's Tax Resistance League and Women's Freedom League. On 10th September 1913 Anne Cobden Sanderson presided over a meeting that explained Harvey's resistance "on the grounds that representation should accompany taxation." (15)

The WFL held protest meetings about what they called a "vindictive sentence". Dr Grace Cadell, who had been fined £50 for refused to stamp the insurance cards of her five servants in the Glasgow High Court, chaired one meeting held by the WFL. At the end of the meeting they sent a message to Reginald McKenna, Home Secretary: "That this meeting protests with indignation against the vindictive sentences passed on voteless women and especially that on Mrs Harvey, and demands that the Government accord equal treatment to men and women under the law and under the constitution." (16)

Charlotte Despard was distraught. With her friend jailed she pined and her ability to work evaporated. Her diary recorded the pain of the estrangement: "The miss of my darling always greater... I think of her first at noon and latest at night... sad and first thoughts always of her, my darling... feelings of deep depression. The days are dragging, very hard to realise she has not been in for a fortnight." (17)

In the event Kate Harvey was released after just a month. The damp cell at Holloway made her so ill that the authorities feared that she might die and let her out a month early. As well as campaigning for women's rights Kate Harvey ran a home for sick and handicapped children, some of whom were paid for by Charlotte Despard. (18)

Harvey was an early practitioner of physiotherapy. As Paul Vallely has pointed out: "She was, for a start, a professional woman in what was very much the man's world of late Victorian Britain. She was, moreover, a professional in that most daring of new disciplines - physiotherapy - about which the British Medical Journal was raising concerns. To many respectable Victorians this biomechanical view of the body in health and illness sounded uncomfortably like a euphemism - physical contact which might get rather too close to the sexual." (19)

Harvey and Despard were inseparable. In the summer of 1913 they went together as delegates from the Women's Freedom League to the seventh Congress of the International Women's Suffrage Alliance in Budapest. At the Hungarian capital the 3,000 suffragist delegates from all over the world were treated with lavish hospitality by the Austro-Hungarian authorities. The two women took the opportunity to visit Hungarian schools and children's clinics. (20)

The First World War

Most members of the Women's Freedom League, were pacifists, and so when the First World War was declared in 1914 they refused to become involved in the British Army's recruitment campaign. The WFL also disagreed with the decision of the NUWSS and WSPU to call off the women's suffrage campaign while the war was on. Leaders of the WFL believed that the British government did not do enough to bring an end to the war and between 1914-1918 supported the campaign of the Women's Peace Crusade for a negotiated peace. The Vote attacked Christabel Pankhurst and Millicent Garrett Fawcett, for condemning the women's peace conference. (21)

Harvey and Despard were both opposed to what they considered to be a "criminal war". They were both distressed by the suffering caused by the war and Harvey turned her Bromley house into a fifty-bed hospital, that catered for refugees and for women and children displaced from the regular hospitals by military patients. The first baby born in the maternity ward was Belgian and several WFL members attended the Christening. (22)

Brackenhill School

In 1916 Kate Harvey and Charlotte Despard bought a large house, Kurundai, and twelve acres overlooking Ashdown Forest near Upper Hartfield in Sussex. It was equipped as a 31 bedroomed hospital for women and children. By 1921 it was in the sole hands of Harvey, who now ran it as a home, hospital and school for disabled children. From 1923 until 1928 the school was operated by the Invalid Children's Aid Association. (23)

In 1928 Harvey established the Brackenhill Theosophical Home School. It was an open-air, vegetarian boarding school with a heavy emphasis on physical exercise. The children lived and played outside as much as possible. They also slept in the open air, in covered shelters. Harvey was also a supporter of the educational ideas of Maria Montessori. This method of teaching was based on spontaneity of expression and freedom from restraint. (24)

Charlotte Despard, at the age of 77, decided to move to Ireland and had transferred her affections to Maud Gonne MacBride, who was twenty-two years her junior. (25). Harvey kept in contact with Despard and in 1934 she wrote to her explaining how she was determined to make her educational experiment successful: "We must not faint or be weary of helping those who need our help badly, so long as we have our share of strength to give." (26)

Helen Smith, the headmistress of Brackenhill School, lived with Kate Harvey at Wroth Tyes, her seven-room detached house in Cat Street, Hartfield. The school closed on the outbreak of the Second World War when the government requisitioned Harvey to be used as part of the war effort. (27)

Felicia Katherine Harvey, died aged 83, on 29th April 1946, leaving effects valued at £14,148 11s. Wroth Tyes was bequeathed to Helen Smith. (28)

Primary Sources

(1) David Simkin, Family History Research (12th November, 2022)

Felicia Catherine Glanvill was born on 30th November 1862 (not 13th November as stated in Wikipedia) in the Peckham district of Camberwell, South London. She was the eldest daughter of Frederick Henry William Glanvill (1843-1879), a "Clerk" (later a "Solicitor's Clerk"), and Felicia Catherine La Thangue (1842-1870), the daughter of an army officer. The union of Frederick and Felicia Glanvill produced 3 daughters - Felicia (born 1862), Edith Mary (born 1866) and Florence Gertrude (born 1869). Felicia Catherine Glanvill lost both parents when young - her mother, Mrs Felicia Catherine Glanvill died in May 1870 when Felicia was 7 years of age; her father, Frederick Glanvill , died on 10th April 1879, when Felicia was 16. (Her father's personal estate was worth less than £200 when he died).

At the time of the 1881 Census, 18-year-old (Felicia) Catherine Glanvill was employed as a "Teacher of English" at a "Ladies' School" in Sevenoaks, Kent (Granville College for Ladies, Principal: Miss Sarah Stanger).

On 24th January 1890, Felicia Catherine Glanvill set sail for India. On 12th November 1890, at Cuddapah, Madras, India, Felicia Catherine Glanvill married Glanvill married Frank Harvey (1854-1905), a Scottish-born "Cotton Merchant" (born 5th May 1854, Renfrewshire, Scotland). This union produced 4 children - Marjorie Glanville Harvey (born 1891 - died 1972), Phyllis Glanville Harvey (born 6th Nov 1898 - died 1922), and twins Rita Glanville Harvey (born 1902 - married poultry farmer Roger Powell in 1924 - died 1988) and Rex Glanville Harvey (born 1902 - died 1906).

At the time of the 1901 Census, Mrs (Felicia Catherine) Kate Harvey residing at a house in Normanton Road, Croydon, Surrey, with her husband - Frank Harvey, a 46-year-old "Cotton Merchant" and their two children - Marjorie, aged 9, and Phyllis, aged 2. The family employed at least 5 servants - a governess, a parlour maid, a kitchen maid, cook, housemaid.

Frank Harvey of Tinniville, Caterham Valley, Surrey, died on 19th September 1905, leaving effects valued at £21,609 12s 6d.

At the time of the 1939 National Register, Katherine F. Harvey (Felicia Catherine Glanvill) was living at Wroth Tyes, Hartfield, Sussex , with her daughter Phyllis Glanville Harvey, a "Masseuse" and Helen K. Smith (born 16th August 1899) a "Junior School Teacher ". 76-year-old Mrs Katherine F. Harvey (Felicia Catherine Glanvill) gives her occupation as "Owner of Wroth Tyes".

Mrs Felicia Katherine Harvey - otherwise Felicia Catherine, otherwise Catherine Felicia, otherwise Kate, of Wroth Tyes, Hartfield, died aged 83, on 29th April 1946, leaving effects valued at £14,148 11s.

Interestingly, on the census returns for 1871, 1881, and 1901, which have columns to indicate disability - no mention is made of her deafness.

(2) The Vote (11th November 1911)

On Saturday, November 4, Mrs. Harvey of "Brackenhill", Highland Road, Bromley, Kent, gave a most successful drawing-room meeting to a new and appreciate audience. Mrs Harvey, who is a loyal supporter of Tax Resistance and had a quantity of her household silver sold in June last, took this opportunity of placing before her friends and neighbours the many reasons which led her to take this action. Mr. Laurence Houseman was the principal speaker, and gave an address of deep interest and instruction on Tax Resistance from the historical standpoint.

(3) Votes for Women (6th December 1912)

On Thursday in last week, a bailiff, accompanied by a Bromley tax-collector and a policeman, forcibly entered the resistance of Mrs Kate Harvey, of the Women's Freedom League. Mrs Harvey's is a Tax Resister and for eight months her house, Brackenhill, Highland Road, Bromley, Kent, has been in a state of siege, the doors being chained and padlocked, while numerous bills until women were politically enfranchised. After filing a chain bound round the garden gate, and three men went to the back door, forced the lock, and gained admittance. In the presence of Mrs Harvey's secretary and servants, a distraint was levied on the dinning-room furniture. Mrs Harvey herself was absent when this action was taken.

(4) The Common Cause (19th September 1913)

As a sequel to Mrs Harvey's imprisonment for non-payment of the insurance tax and licence for manservants, meetings are being held every Monday and Wednesday night in the Market Square, Bromley, by the Women's Tax Resistance League and Women's Freedom League, Mrs Harvey being a member of both Societies. On September 10 th Mrs Cobden Sanderson presided over an attentive meeting and explained Mrs Harvey's resistance on the grounds that representation should accompany taxation. She was followed by two Californian ladies, Mrs Wilks and Miss Grover-Smith, both of whom now enjoy the vote in their own country and voted in the recent election for President Wilson. Mrs Wilks in a Unitarian minister, and worked for the suffrage for fifty years.

(5) Edinburgh Evening News (22nd September 1913)

A largely attended meeting was held at the mound on Saturday afternoon, to protest against the "vindictive" sentence of two months imprisonment passed on Mrs Kate Harvey of the Women's Freedom League who refused to pay insurance tax on behalf of her gardener, Asquith. Dr Grace Cadell, herself an Insurance Tax resister, took the chair. Dr Cardell remarked that although she has not paid the fine imposed she is not yet imprisoned, presumably because of the Clerk of the Court is unable to answer her question as to how a "person" in the eyes of the law. The close of the meeting found the audience in entire sympathy with the speakers, and with three dissentients the following resolution was passed, and has been sent to Mr McKenna, Home Secretary: "That this meeting protests with indignation against the vindictive sentences passed on voteless women and especially that on Mrs Harvey, and demands that the Government accord equal treatment to men and women under the law and under the constitution."

(6) Paul Vallely, The Independent (23rd November 2005)

Kate Harvey was a remarkable woman, even without the incident which lies at the heart of the commendation. She was, for a start, a professional woman in what was very much the man's world of late Victorian Britain. She was, moreover, a professional in that most daring of new disciplines - physiotherapy - about which the British Medical Journal was raising concerns. To many respectable Victorians this biomechanical view of the body in health and illness sounded uncomfortably like a euphemism - physical contact which might get rather too close to the sexual - a view which altered only after spinal injury units and orthopaedic hospitals were introduced after the First World War...

The mother of three daughters, Mrs Harvey was widowed early and took up good work among the poor. She opened a home for handicapped children in Bromley. There she came into contact with another young widow, Charlotte Despard, who had taken a similar turn towards good works after the death of her husband, opening a social services centre for the needy in Wandsworth...

Despard is the better-known of the two figures. She was born in Kent but developed radical political views when she moved to London and was shocked by the poverty she saw. She made her living writing romantic novels until she penned A Voice from the Dim Millions, which dealt with the problems of a poor young factory worker. But when no-one would publish it, she dedicated herself to the poor. She left her luxurious house in Esher for London where, in 1894, she was elected as a Poor Law Guardian in Lambeth.

Over the next few years she became friends with George Lansbury and Keir Hardie, two of the Labour Party's earliest and most radical leaders. Into this world she drew Kate Harvey and inevitably the pair became involved in the movement to win votes for women.

But, like all movements driven by idealism rather than political pragmatism, the movement was prone to fracture. Charlotte Despard had been a big figure in the Women's Social and Political Union, led by the prominent suffragettes Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst. Despard was arrested and imprisoned for her activities, but she was too radical for the autocratic Pankhursts. In 1907 she led 70 other women in breaking away from the WSPU in protest at the Pankhurst's high-handed and dictatorial style.

They formed a more democratic organisation, the Women's Freedom League, with Despard as its President and Harvey - playing Alastair Campbell to Despard's Blair - its Honorary Press Secretary. The new organisation took a more militant, though non-violent approach.

In 1909 Despard met Gandhi and fell under the influence of his theory of "passive resistance". She urged upon their members a campaign of civil disobedience, calling on women not to pay the newly-introduced National Insurance tax on servants' wages.

Some 10,000 women declined to pay the new tax. They were not all suffragettes; several were simply women who ignored or disliked the business of buying a weekly stamp for servants. A few, who were self-employed, refused to buy their own stamps, and some were bankrupted by the Inland Revenue for their protest. Around 100 women were sent to prison for refusing to pay.

The most notorious of these was Mrs Harvey. After many months of refusing to buy a stamp for her servant, in 1912 the authorities issued a warrant for the seizure of goods in lieu of payment. She responded by barricading herself into her house. An eight month stand-off passed before bailiffs finally broke in using a crowbar. But a year later she still refused to pay, declaring "I would rather die first". She set about building better barricades. This time the bailiffs needed battering rams to get in.

Her long battle drew the attention of the press, not least because, serendipitously, the name of the servant whose weekly National Insurance stamp Mrs Harvey refused to buy was called Asquith - which also happened to be the name of the Prime Minister. The authorities decided to make an example of her and sent her to prison for two months.