On this day on 25th August

On this day in 1819 James Watt died.

James Watt, the eldest surviving child of eight children, five of whom died in infancy, of James Watt (1698–1782) and his wife, Agnes Muirhead (1703–1755), was born in Greenock on 19th January, 1736. His father was a successful merchant.

According to his biographer, Jennifer Tann: "James Watt was a delicate child and suffered from frequent headaches during his childhood and adult life. He was taught at home by his mother at first, then was sent to M'Adam's school in Greenock. He later went to Greenock grammar school where he learned Latin and some Greek but was considered to be slow. However, on being introduced to mathematics, he showed both interest and ability."

At the age of nineteen he was sent to Glasgow to learn the trade of a mathematical-instrument maker. After spending a year in London, Watt returned to Scotland in 1757 where he established his own instrument-making business. Watt soon developed a reputation as a high quality engineer and was employed on the Forth & Clyde Canal and the Caledonian Canal. He was also engaged in the improvement of harbours and in the deepening of the Forth, Clyde and other rivers in Scotland.

James Watt became very interested in the subject of steam power. In 1761 he got hold of a steam digester, a type of pressure cooker with a safety valve. It had been created by Denis Papin, a French mathematician. He looked at ways of improving the machine. He fixed an ordinary apothecary's syringe to the valve, and put a little piston inside it with a rod pointing out of the top. Between digester and syringe he fitted a steam cock which he could turn so that the steam either filled the syringe or escaped.

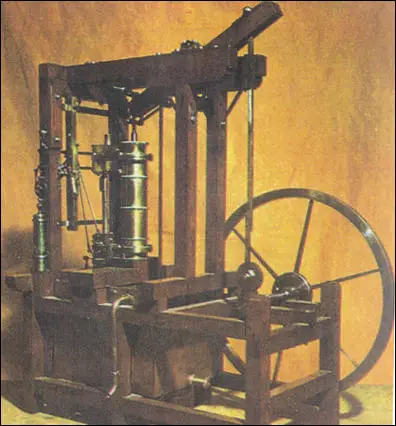

Thomas Savery had also tried to improve Papin's machine. One of the major problems of mining for coal, iron, lead and tin in the 17th and 18th centuries was flooding. Miners used several different methods to solve this problem. These included pumps worked by windmills and teams of men and animals carrying endless buckets of water. Savery used Papin's idea of using a cylinder and a piston to design a pumping engine which incorporated two different ways of utilizing steam to generate power. Steam was pumped into a cylinder and then cooled so that a vacuum was formed and atmospheric pressure drew water up.

On 25th July 1698 Thomas Savery obtained a patent for fourteen years. The patent contained no description of the machine, but in June 1699 it was shown to members of the Royal Society. Savery established a workshop at Salisbury Court, London. At this workshop, mine and colliery owners could see the engine demonstrated before purchase. However, the engine could not raise water from very deep mines. Another disadvantage was its tendency to cause explosions.

In 1763 Watt was sent a steam engine produced by Thomas Newcomen to repair. Newcomen, an inventor from Dartmouth , had also attempted to improve on the machines produced by Papin and Savery. He eventually came up with the idea of a machine that would rely on atmospheric air pressure to work the pumps, a system which would be safe, if rather slow. The "steam entered a cylinder and raised a piston; a jet of water cooled the cylinder, and the steam condensed, causing the piston to fall, and thereby lift water."

As Jenny Uglow has pointed out: "Newcomen's engines exploited basic atmospheric pressure, building on the way had been found to rush into a vacuum. A vacuum could be created by sucking air out of a closed vessel with a pump, but it could also be created by using steam."

Newcomen and his partner, John Calley, produced their first steam engine in 1710. John Theophilus Desaguliers points out: "In the latter end of the year 1711 made proposals to draw the water at Griff, in Warwickshire; but their invention meeting not with reception... after a great many laborious attempts, they did make the engine work; but not being either philosophers to understand the reason, or mathematicians enough to calculate the powers and to proportion the parts, very luckily by accident found what they sought for."

The steam-engine was set up next to the mine it was draining. It had a large, rocking overhead beam. From one end hung a chain which was attached to the top of a piston encased in a cylinder. According to Gavin Weightman, the author of The Industrial Revolutionaries (2007), Newcomen and Calley had "devised and brought to efficient working order was the first really reliable steam engine in the world".

Following the undoubted success of this engine a number of others were built in which Newcomen himself was involved. They included collieries at Griff, Warwickshire (1711); Bilston, Staffordshire (1714); Hawarden, Flintshire (1715); Austhorpe, West Yorkshire (1715) and Whitehaven, Cumberland (1715).

Although many mine-owners used Newcomen's steam-engines, they constantly complained about the cost of using them. The main problem with it was they used a great deal of coal and were therefore expensive to run. While putting it back into working order, Watt attempted to discover how he could make the engine more efficient.

Watt later told his friend, the Glasgow engineer, Robert Hart: "I had gone to take a walk on a fine Sabbath afternoon. I passed the old washing-house. I was thinking upon the engine at the time and had gone as far as the Herd's house when the idea came into my mind, that as steam was an elastic body it would rush into a vacuum, and if a communication was made between the cylinder and an exhausted vessel, it would rush into it, and might be there condensed without cooling the cylinder."

Watt worked on the idea for several months and eventually produced a steam engine that cooled the used steam in a condenser separate from the main cylinder. Watt calculated that this would produce a saving of fuel of around 75 per cent. It has been argued by Jennifer Tann that "Watt identified several problems, of which the wastage of steam during the ascent of the engine piston and the method of vacuum formation in which the system was cooled were two of the most fundamental. He therefore made a new model, slightly larger than the original, and conducted many experiments on it.... The theory of latent heat underpinned Watt's experiments on the separate condenser, in which the steam cylinder remained hot while a separate condensing vessel was cold."

In April, 1765, James Watt wrote to James Lind about his invention. "I have now almost a certainty of the facturum of the fire-engine, having determined the following particulars: the quantity of steam produced; the ultimatum of the lever engine; the quantity of steam produced; the quantity of steam destroyed by the cold of its cylinder; the quantity destroyed in mine... mine ought to raise water to 44 feet with the same quantity of steam that there does to 32 (supposing my cylinder as thick as theirs). I can now make a cylinder of 2 feet diameter and 3 feet high only a 40th of an inch thick, and strong enough to resist the atmosphere... in short, I can think of nothing else but this machine."

James Watt built an instrument-maker's model but the next stage involved producing a massive working engine made of brick and iron. Watt had no money for large-scale models and so he had to seek a partner with capital. Watt's friend, Joseph Black, introduced him to John Roebuck, the owner of Carron Ironworks near Falkirk in Scotland. He also owned nearby coal mines to provide fuel for his ironworks.

Roebuck agreed and the two men went into partnership. Roebuck held two-thirds of the original patent (9th January 1769) in return for discharging some of Watt's debts. James Patrick Muirhead, the author of The Life of James Watt (1854) claims that Roebuck's made every effort to get Watt's machine into production as he was "ardent and sanguine in the pursuit of his undertakings".

In March 1773 Roebuck became bankrupt. At the time he owed Matthew Boulton over £1,200. Boulton knew about Watt's research and wrote to him making an offer for Roebuck's share in the steam-engine. Roebuck refused but on 17th May, he changed his mind and accepted Boulton's terms. James Watt was also owed money by Roebuck, but as he had done a deal with his friend, he wrote a formal discharge "because I think the thousand pounds he (Boulton) he has paid more than the value of the property of the two thirds of the inventions."

Roger Osborne, the author of Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution (2013) has argued: "The two men instantly knew they could work together. Perhaps Watt saw that Boulton was the necessary complement to his own gloomy character - an energetic optimist who would carry him through his difficulties - while Boulton surely recognised the seriousness of Watt's character.... Watt was delighted not just by the prospect of investment hut especially by Boulton's personal enthusiasm."

Boulton pointed out that before he would give Watt financial backing, he insisted that the 1769 patent, with only eight years to run, should be extended to twenty-five years. This meant petitioning the House of Commons. By 1775 the two men had their patent which gave them "the sole use and property of certain steam-engines of his invention, throughout the majesty's dominions." This prevented others from making steam-engines which contained improvements of their own.

Under the terms of the partnership Watt assigned two-thirds of both property and the patent to Boulton. In return Boulton undertook to pay the expenses already incurred, to meet the costs of experiments, and to pay for materials and wages. The profits were to be divided in proportion to their shares. "It would be incorrect to stereotype Boulton as the entrepreneur and Watt as the inventor, for Boulton made many suggestions for improvements to the engine and Watt also had a good head for business. But there is no doubt that Boulton's flair for marketing was significant for the early success of the business."

For the next eleven years Boulton's factory produced and sold Watt's steam-engines. These machines were mainly sold to colliery owners who used them to pump water from their mines. Watt's machine was very popular because it was four times more powerful than those that had been based on the Thomas Newcomen design.

One of their machines was installed at Whitbread's Brewery in London in 1775 to grind malt and raise the liquor, taking the place of a huge wheel which needed six horses at a time to turn it. The company was very pleased with the economic benefits of Watt's steam engine that had cost them £1,000.

Watt continued to experiment and in 1781 he produced a rotary-motion steam engine. Whereas his earlier machine, with its up-and-down pumping action, was ideal for draining mines, this new steam engine could be used to drive many different types of machinery. Richard Arkwright was quick to importance of this new invention, and in 1783 he began using Watt's steam-engine in his textile factories.

The ironmaster John Wilkinson, was one of the first people to buy Watt's steam engine. He installed eleven engines at his Bradley ironworks by the 1790s and at least seven elsewhere. The partners depended heavily on Wilkinson for it was he who was capable of boring engine cylinders with greater accuracy than any other iron-founder. His boring machine has been called the first machine tool that was developed in the industrial revolution.

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that James Watt's steam engine was "the foundation of industrial technology". Arthur Young commented in his book, Tours in England and Wales (1791) about the impact that Watt had on Britain: "What trains of thought, what a spirit of exertion, what a mass and power of effort have sprung in every path of life, from the works of such men as Brindley, Watt, Priestley, Harrison, Arkwright.... In what path of life can a man be found that will not animate his pursuit from seeing the steam-engine of Watt?"

Richard Guest pointed out that Watt's steam engine that drove the power looms was extremely popular with factory owners: "The increasing number of steam-looms is a certain proof of their superiority over the hand-looms. In 1818, there were in Manchester, Stockport, Middleton, Hyde, Stayley Bridge, and their vicinities, 14 factories, containing about 2,000 looms. In 1821, there were in the same neighbourhoods 32 factories, containing 5,732 looms. Since 1821, their number has still increased, and there are at present not less than 10,000 steam-looms at work in Great Britain."

Boulton & Watt company had a virtual monopoly over the production of steam-engines. Watt charged his customers a premium for using his steam engines. To justify this he compared his machine to a horse. Watt calculated that a horse exerted a pull of 180 lb., therefore, when he made a machine, he described its power in relation to a horse, i.e. "a 20 horse-power engine". Watt worked out how much each company saved by using his machine rather than a team of horses. The company then had to pay him one third of this figure every year, for the next twenty-five years.

Henry Brougham later recalled: "There was one quality, which most honourably distinguished him from too many inventors, and was worthy of all imitation, he was not only entirely free from jealously, but he exercised a careful and scrupulous self-denial, and was anxious not to appear, even by accident, as appropriating to himself that which he thought belonged to others."

James Watt became an important member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham. The group took this name because they used to meet to dine and converse on the night of the full moon. The group grew out of a friendship between Matthew Boulton and Erasmus Darwin and first began meeting as a group in 1768. Other members included Josiah Wedgwood, Joseph Priestley, James Brindley, Thomas Day, William Small, John Whitehurst, John Robison, Joseph Black, William Withering, John Wilkinson, Richard Lovell Edgeworth and Joseph Wright.

The historian, Jenny Uglow, has argued: "It has been said that the Lunar Society kick-started the industrial revolution. No individual or group can be said to change a society in such a way, and time and again one can see that if they hadn't invented or discovered something, someone else would have done it. Yet this small group of friends really was at the leading edge of almost every movement of its time in science, in industry and in the arts, even in agriculture. They were pioneers of the turnpikes and canals and of the new factory system. They were the group who brought efficient steam power to the nation." (29)

Watt deeply felt the loss of some of his friends from the Lunar Society. A number of Watt's friends died at the turn of the century. Josiah Wedgwood (1795), Joseph Black (1799), Erasmus Darwin (1802), Joseph Priestley (1804) and John Robison (1805). It is claimed that in retirement he was haunted by the fear that his mental faculties were failing.

Watt's partner, Matthew Boulton, suffered from stones in the kidneys, and he told a friend: "My doctors say my only chance of continuing in this world depends on my living quiet in it." (31) He died aged 81 of kidney failure on 17th August 1809. Watt wrote that Boulton was "not only an ingenious mechanic, well skilled in all the practices of the Birmingham manufacturers, but possessed in a high degree the faculty of rendering any new invention of his own or others useful to the public, by organising and arranging the processes by which it could be carried on."

James Watt died aged 73 at Heathfield in Handsworth, Birmingham, on 25th August 1819 and was buried beside Matthew Boulton in St Mary's Church on 2nd September 1819. He left over £60,000 (£81,000,000 in today's money) in his will to his family.

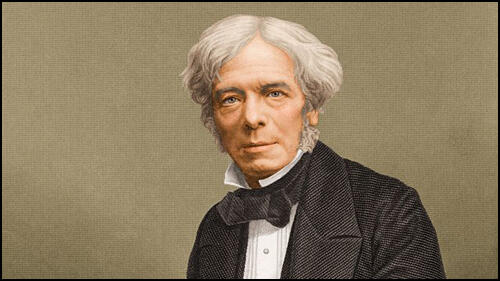

On this day in 1867 scientist Michael Faraday died at his home, The Green, Hampton Court. He was buried five days later in the Sandemanian plot in Highgate cemetery.

Michael Faraday, the third of four children of James Faraday (1761–1810) and his wife, Margaret Hastwell Faraday (1764–1838), was born in Newington Butts on 22nd September 1791. James Faraday and all his children belonged to the small Christian sect called in Scotland the Glasites after their founder, John Glas, and in England the Sandemanians, after Robert Sandeman, who had brought these religious views to the country. Faraday worked as a blacksmith with James Boyd, a Sandemanian ironmonger of Welbeck Street, London.

Faraday later recalled: "my education was of the most ordinary description, consisting of little more than the rudiments of reading, writing, and arithmetic at a common day-school. My hours out of school were passed at home and in the streets". In 1804 he became an errand boy, delivering among other things newspapers, for the bookseller George Riebau of 2 Blandford Street. In October 1805, at the age of fourteen, he was indentured for seven years to Riebau as an apprentice bookbinder. It was during this apprenticeship that he developed an interest in chemistry. Faraday wrote: "whilst an apprentice, I loved to read the scientific books which were under my hands." He later thanked Riebau for helping him in his education: "you kindly interested yourself in the progress I made in the knowledge of facts relating to the different theories in existence, readily permitting me to examine those books in your possession that were in any way related to the subjects occupying my attention." This included reading books by Jane Marcet (Conversations on Chemistry) and Isaac Watts (Improvement of the Mind).

In the spring of 1812, the year his apprenticeship ended, William Dance, a customer of Riebau's, gave Faraday tickets to attend four lectures to be delivered by the professor of chemistry at the Royal Institution, Humphry Davy. He later recalled: "Sir H. Davy proceeded to make a few observations on the connections of science with other parts of polished and social life. Here it would be impossible for me to follow him. I should merely injure and destroy the beautiful and sublime observations that fell from his lips. He spoke in the most energetic and luminous manner of the Advancement of the Arts and Sciences. Of the connection that had always existed between them and other parts of a Nation's economy. During the whole of these observations his delivery was easy, his diction elegant, his tone good and his sentiments sublime." After becoming interested in science, Faraday applied to Davy for a job. In 1813 Faraday became his temporary assistant and spent the next 18 months touring Europe while during Davy's investigations into his theory of volcanic action.

His biographer, Frank James, wrote: "Davy had obtained a special passport from Napoleon stipulating that he could be accompanied only by his wife and two others. With Jane Davy requiring a maid, Davy (claiming that his valet had suddenly withdrawn) asked Faraday to undertake the tasks of a valet, making a promise, never fulfilled, to find a valet once they were on the continent. Faraday reluctantly agreed but this was the source of considerable friction between him and Jane Davy, who regarded him as a servant. For eighteen months they toured France, Switzerland, Italy, and southern Germany visiting many chemical laboratories. They met, among others, André-Marie Ampère in Paris, Charles-Gaspard and Arthur-Auguste De La Rive in Geneva, and the aged Alessandro Volta in Italy. Davy demonstrated the elemental nature of iodine to the French and in Florence showed that diamond was composed of carbon using the burning-glass of the duke of Tuscany. They witnessed the end of Napoleon's empire but following Napoleon's escape from Elba for the hundred days Davy decided to cut short the tour and returned to England in the middle of April 1815."

Faraday was also inspired by the work of Joseph Priestley: "Dr. Priestley had that freedom of mind, and that independence of dogma and of preconceived notions, by which men are so often bowed down and carried forward from fallacy to fallacy, their eyes not being opened to see what that fallacy is. I am very anxious at this time to exhort you all, - as I trust you all are pursuers of science, - to attend to these things; for Dr Priestley made his great discoveries mainly in consequence of his having a mind which could be easily moved from what it had held to the reception of new thoughts and notions; and I will venture to say that all his discoveries followed from the facility with which he could leave a preconceived idea."

On 21 May 1821 Faraday was appointed acting superintendent of the house of the Royal Institution. The following month he married Sarah Barnard (1800–1879), daughter of the Sandemanian silversmith Edward Barnard (1767–1855). From the evidence that has survived the Faradays's marriage appears to have been happy and she was very supportive of his work. Although they had no children, at least two nieces lived with them for extended periods, Margery Ann Reid (1815–1888) and Jane Barnard (1832–1911).

Humphry Davy gave Faraday a valuable scientific education and also introduced him to important scientists in Europe. One scientist, Henry Paul Harvey, commented: "Sir H. Davy's greatest discovery was Michael Faraday." After Davy retired in 1827, Faraday replaced him as professor of chemistry at the Royal Institution. Faraday began to publish details of his research including condensation of gases, optical deceptions and the isolation of benzene from gas oils.

Faraday's greatest contribution to science was in the field of electricity. In 1821 he began experimenting with electromagnetism and by demonstrating the conversion of electrical energy into motive force, invented the electric motor. In 1831 Faraday discovered the induction of electric currents and made the first dynamo. In 1837 he demonstrated that electrostatic force consists of a field of curved lines of force, and conceived a specific inductive capacity. This led to Faraday being able to develop his theories on light and gravitational systems.

Harper's Magazine published an article stating: "At no period of Michael Faraday's unmatched career was he interested in utility. He was absorbed in disentangling the riddles of the universe, at first chemical riddles, in later periods, physical riddles. As far as he cared, the question of utility was never raised. Any suspicion of utility would have restricted his restless curiosity. In the end, utility resulted, but it was never a criterion to which his ceaseless experimentation could be subjected." William Ewart Gladstone, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, once asked Michael Faraday about the practical worth of electricity. He said he did not know but "there is every probability that you will soon be able to tax it!"

Michael Faraday told a friend: "I have never had any student or pupil under me to aid me with assistance; but have always prepared and made my experiments with my own hands, working and thinking at the same time. I do not think I could work in company, or think aloud, or explain my thoughts at the time. Sometimes I and my assistant have been in the Laboratory for hours & days together, he preparing some lecture apparatus or cleaning up, & scarcely a word has passed between us; - all this being a consequence of the solitary & isolated system of investigation; in contradistinction to that pursued by a Professor with his aids & pupils as in your Universities."

Faraday was very keen to educate the public on science. In one lecture he argued: "If the term education may be understood in so large a sense as to include all that belongs to the improvement of the mind, either by the acquisition of the knowledge of others or by increase of it through its own exertions, we learn by them what is the kind of education science offers to man. It teaches us to be neglectful of nothing - not to despise the small beginnings, for they precede of necessity all great things in the knowledge of science, either pure or applied."

Friedrich Von Raumer was one of those impressed by the lecturers of Faraday: "He (Michael Faraday) speaks with ease and freedom, but not with a gossipy, unequal tone, alternately inaudible and bawling, as some very learned professors do; he delivers himself with clearness, precision and ability. Moreover, he speaks his language in a manner which confirmed me in a secret suspicion that I had, that a number of Englishmen speak it very badly."

Jane Pollack wrote in the St. Paul's Magazine that Faraday was an outstanding speaker: "It was an irresistible eloquence which compelled attention and invited upon sympathy. There was a gleaming in his eyes which no painter could copy, and which no poet could describe. Their radiance seemed to send a strange light into the very heart of his congregation, and when he spoke, it was felt that the stir of his voice and the fervour of his words could belong only to the owner of those kindling eyes. His thought was rapid and made its way in new phrases. His enthusiasm seemed to carry him to the point of ecstasy when he expatiated on the beauties of Nature, and when he lifted the veil from her deep mysteries. His body then took motion from his mind; his hair streamed out from his head; his hands were full of nervous action; his light, lithe body seemed to quiver with its eager life. His audience took fire with him, and every face was flushed."

The physicist, John Tyndall, recalled: "Underneath his sweetness and gentleness was the heat of a volcano. He was a man of excitable and fiery nature; but through high self-discipline he had converted the fire into a central glow and motive power of life, instead of permitting it to waste itself in useless passion. Faraday was not slow to anger, but he completely ruled his own spirit, and thus, though he took no cities, he captivated all hearts."

Faraday became a close friend of Angela Burdett-Coutts. According to Edna Healey, the author of Lady Unknown: The Life of Angela Burdett-Coutts (1978): "In Michael Faraday she found a brilliant, searching mind combined with a simple child-like faith that matched her own. The greatest experimental genius of his time, the man who discovered the laws of electrolysis, of light and magnetism, he was at ease in her company. The blacksmith's son who hated the social scene, made exceptions for her... As their friendship grew, he would call on her after the Friday lectures at the Royal Institution, eventually persuading her to apply for membership of the Royal Society."

On 19th January, 1847, Faraday wrote to Miss Burdett-Coutts: "For twenty years I have devoted all my exertions and powers to the advancement of science in this Institution; and for the last ten years or more I have given up all professional business and a large income with it for the same purpose... Although I earnestly desire to see lady members received amongst us, as in former times, do not let anything I have said induce you to do what may be not quite agreeable to your own inclinations." In February 1847 she became a full member of the Royal Society.

Michael Faraday rejected the Presidency of the Royal Society. He told John Tyndall: "Tyndall... I must remain plain Michael Faraday to the last; and let me now tell you, that if accepted the honour which the Royal Society desires to confer upon me, I would not answer for the integrity of my intellect for a single year. On being offered the Presidency of the Royal Society."

The government recognized his contribution to science by granting him a pension and giving him a house in Hampton Court. However, Faraday was unwilling to use his scientific knowledge to help military action and in 1853 refused to help develop poison gases to be used in the Crimean War. Faraday was the author of several books including Experimental Researches in Electricity and Chemical History of the Candle.

In 1853 spiritualism and table-turning became fashionable. Faraday examined the phenomenon and came to the conclusion that table-turning was caused by a quasi-involuntary muscular action, and had nothing to do with supernatural agency. In a letter to The Times stating his results, Faraday concluded by saying that the educational system must be deficient since otherwise well-educated people would not believe in the phenomenon in the way they did.

His biographer, Frank James, has pointed out: "In 1856 Faraday started his last major research project. Following George Gabriel Stokes's work on fluorescence in the early 1850s, which showed that a ray of light could change its wavelength after passing through a solution of sulphate of quinine, Faraday tried to realize this change directly. To achieve this he passed light through beaten gold and later colloidal solutions of gold. The wavelength of light was larger than the size of the gold particles, and yet they still affected the light. He sought to explain this phenomenon but, as with his work on gravity, came to no firm conclusions. Faraday's last piece of experimental work in 1862 was to see if magnetism had any effect on line spectra."

Michael Faraday died at his home, The Green, Hampton Court, where he died on 25th August 1867. He was buried five days later in the Sandemanian plot in Highgate cemetery.

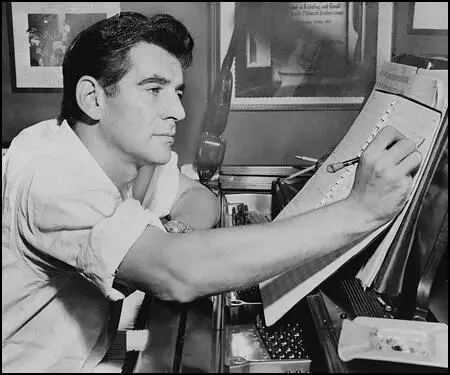

On this day in 1918 Leonard Bernstein is born in Lawrence, Massachusetts. He attended Harvard University and the Curtis Institute of Music (1939-41) before studying under Fritz Reiner and Serge Koussevitzky.

After working as assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic he became conductor of New York City Center (1945-47). He also wrote the music for Fancy Free (1943) and On the Town (1944).

After the Second World War the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began to investigate people with left-wing views in the entertainment industry. In June, 1950, three former FBI agents and a right-wing television producer, Vincent Harnett, published Red Channels, a pamphlet listing the names of 151 writers, directors and performers who they claimed had been members of subversive organizations before the Second World War but had not so far been blacklisted. The names had been compiled from FBI files and a detailed analysis of the Daily Worker, a newspaper published by the American Communist Party.

A free copy of Red Channels was sent to those involved in employing people in the entertainment industry. All those people named in the pamphlet were blacklisted until they appeared in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and convinced its members they had completely renounced their radical past.

Bernstein was one of those named but he continued to be commissioned to write the music for films including On the Waterfront (1954), West Side Story (1961), To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) and Terms of Endearment(1983).

Leonard Bernstein died in New York on 14th October, 1990.

On this day in 1919 George Wallace, the son of a farmer, was born in Clio, Alabama. He studied at the University of Alabama and received his law degree in 1942.

Wallace served in the United States Army Air Force during the Second World War. After the war he became assistant attorney general of Alabama before being elected as a member of the Alabama Legislature in 1947. Wallace also served as judge of the Third Judicial District of Alabama (1953-1958).

A member of the Democratic Party, Wallace attempted in 1958 to become his party's candidate for governor of Alabama. His main rival, John Patterson, Alabama's Attorney General, was an outspoken segregationist who had become a popular hero with white racists by using the state courts to declare the NAACP in Alabama an illegal organization. Patterson was endorsed by the Ku Klux Klan and easily defeated Wallace.

After the election Patterson admitted that: "The primary reason I beat him (Wallace) was because he was considered soft on the race question." Wallace agreed and decided to drop his support for integration and was quoted as saying: "no other son-of-a-bitch will ever out-nigger me again".

One of the ways that Wallace improved his racist credentials was to recruit Asa Earl Carter as his main speechwriter in the 1962 election. Carter, the head of a Ku Klux Klan terrorist organisation, was one of the most extreme racists in Alabama. Carter wrote most of Wallace's speeches during the campaign and this included the slogan: "Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! Segregation forever!"

During the campaign to become governor of Alabama in 1962 he told audiences that if the federal government sought to integrate Alabama's schools, "I shall refuse to abide by any such illegal federal court order even to the point of standing in the schoolhouse door." Wallace campaign was popular with the white voters and he easily won the election.

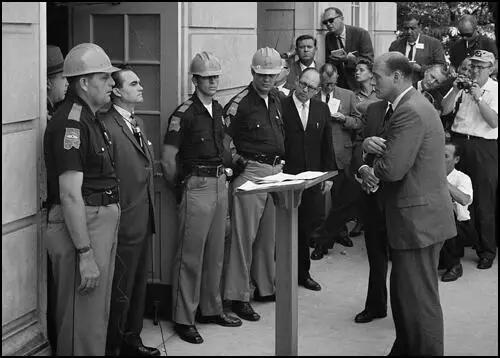

In June 1963, Wallace blocked the enrollment of African American students at the University of Alabama. Similar actions in Birmingham, Huntsville and Mobile made him a national figure and one of the country's leading figures against the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King told one journalist in 1963 that Wallace was "perhaps the most dangerous racist in America today."

Wallace continued to resist the demands of John F. Kennedy and the federal government to integrate the Alabama's education system. On 5th September he ordered schools in Birmingham to close and told the the New York Times that in order to stop integration Alabama needed a "few first-class funerals."

A week later a bomb exploded outside the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, killing four schoolgirls who had been attending Sunday school classes. Twenty-three other people were also hurt by the blast.

Alabama law barred Wallace from standing as governor for a second term in 1966. His wife, Lurleen Wallace, stood instead and her victory determined that Wallace would retain power.

In February, 1968, George Wallace announced his intention of standing as an independent candidate for president. His hostility to civil rights legislation won him support from white voters in the Deep South and won Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia. Although he won over 9 million votes he came third to Richard Nixon ( 31,770,237) and Hubert Humphrey (31,270,533).

Nixon was concerned that Wallace would stand as a third party candidate in the next election. Nixon’s initial strategy was to destroy Wallace’s power base in Alabama. This included providing $400,000 to try and help Albert Brewer defeat Wallace as governor. This strategy failed and in 1970 Wallace won a landslide victory for a second term as governor of Alabama.

This failed and Richard Nixon had to change his strategy to one of blackmail. With the help of Murray Chotiner, Nixon discovered details of Wallace’s corrupt activities in Alabama. In July 1969, Nixon pressurized the IRS into forming the Special Services Staff (SSS). The role of the SSS was to target Nixon’s political enemies. By 1970 the SSS had compiled a list of 4,000 individuals. Most of this list were on the left. However, Nixon now added Wallace and several of his aides to this list. This included George’s brother, Gerald Wallace, who had indeed made a fortune from his business activities. This included a $2.9 million contract for asphalt that went to Gerald's company even though he charged a $2.50 per ton over the going price. By August 1970, the SSS had 75 people working on what was known as the “Alabama Project”.

To show that Nixon meant business, one of Wallace’s closest aides, Seymore Trammell, was sent to prison for 4 years for corruption. Nixon then used Winston Blount, his Postmaster General, to begin negotiations with Wallace. A deal was eventually struck with Wallace. In return for calling off the SSS Wallace made a statement that he would not become a third party candidate. On 12th January, 1972, Attorney General John N. Mitchell announced he was not going to prosecute Gerald Wallace. The following day Wallace gave a press conference where he announced he would not be a third party candidate.

It soon became certain that George McGovern would get the nomination of the Democratic Party. However, Wallace did much better than expected. Richard Nixon now feared that Wallace would not keep his promise and become a third party candidate. Polls suggested that virtually all of Wallace’s votes would come from Nixon’s potential supporters. If Wallace stood, Nixon faced the prospect of being defeated by McGovern.

On 15th May, 1972, Arthur Bremer tried to assassinate Wallace. at a presidential campaign rally in Laurel, Maryland. Wallace was hit four times. Three other people, Alabama State Trooper Captain E. C. Dothard, Dora Thompson, a Wallace campaign volunteer, and Nick Zarvos, a Secret Service agent, were also wounded in the attack.

Mark Felt of the Federal Bureau of Investigation immediately took charge of the case. According to the historian Dan T. Carter (The Politics of Rage), Felt had a trusted contact in the White House: Charles Colson. Felt gave Colson the news. Within 90 minutes of the shooting Richard Nixon and Colson are recorded discussing the case. Nixon told Colson that he was concerned that Bremer “might have ties to the Republican Party or, even worse, the President’s re-election committee”. Nixon also asked Colson to find a way of blaming George McGovern for the shooting.

Over the next few hours, Colson and Felt talk six times on the telephone. Felt gave Colson the address of Bremer's home. Colson now phoned E. Howard Hunt and asked him to break-in to Bremer's apartment to discover if he had any documents that linked him to Nixon or George McGovern. According to Hunt's autobiography, Undercover, he disliked this idea but made preparations for the trip. He claimed that later that night Colson calls off the operation.

At 5:00 p.m. Thomas Farrow, head of the Baltimore FBI, passed details of Bremer’s address to the FBI office in Milwaukee. Soon afterwards two FBI agents arrived at Bremer’s apartment block and begin interviewing neighbours. However, they do not have a search warrant and do not go into Bremer’s apartment.

At around the same time, James Rowley, head of the Secret Service, ordered one of his Milwaukee agents to break into Bremer’s apartment. It has never been revealed why Rowley took this action. It is while this agent is searching the apartment that the FBI discover what is happening. According to John Ehrlichman, the FBI was so angry when they discovered the Secret Service in the apartment that they nearly opened fire on them.

The Secret Service took away documents from Bremer’s apartment. It is not known if they planted anything before they left. Anyway, the FBI discovered material published by the Black Panther Party and the American Civil Liberties Union in the apartment. Both sets of agents now left Bremer’s apartment unsealed. Over the next 80 minutes several reporters enter the apartment and take away documents.

Charles Colson also phoned journalists at the Washington Post and Detroit News with the news that evidence had been found that Bremer is a left-winger and was connected to the campaign of George McGovern. The reporters were also told that Bremer is a “dues-paying member of the Young Democrats of Milwaukee”. The next day Bob Woodward (Washington Post) and Gerald terHost (Detroit News) publish this story.

The following day that the FBI discovered Bremer’s 137-page written diary in his blue Rambler car. The opening sentence was: "Now I start my diary of my personal plot to kill by pistol either Richard Nixon or George Wallace." Nixon was initially suspected of being behind the assassination but the diary gets him off the hook. The diary was eventually published as a book, An Assassin's Diary (1973).

George Wallace survived the assassination attempt. He gradually developed the view that one Nixon’s aides ordered the assassination. To gain revenge he announces he is to become a third party candidate. However, Wallace’s health has been severely damaged and reluctantly he had to pull out of the race.

In May, 1974, Martha Mitchell visited Wallace in Montgomery. She told him that her husband, John N. Mitchell, had confessed that Charles Colson had a meeting with Arthur Bremer four days before the assassination attempt.

Wallace ordered his own investigation into Bremer. He told friends that he was convinced that Nixon’s aides had arranged the assassination. Wallace gave an interview to Jack Nelson of the Los Angeles Times. Wallace told Nelson that the man seen talking to Bremer on the Lake Michigan Ferry looked very much like G. Gordon Liddy.

Wallace was partially paralyzed as a result of the attack by Arthur Bremer. After a long spell in hospital Wallace was able to return to politics. He apologized for his previous stance of civil rights and during the 1982 won the governorship with substantial support from African American voters.

Ill-health forced Wallace to retire from politics in 1987. He continued his support of integration and in March, 1995, Wallace attended the re-enactment of the Selma to Montgomery civil rights march.

George Wallace died on 13th September, 1998.

being confronted by Deputy U.S. Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach on 11th July 1963.

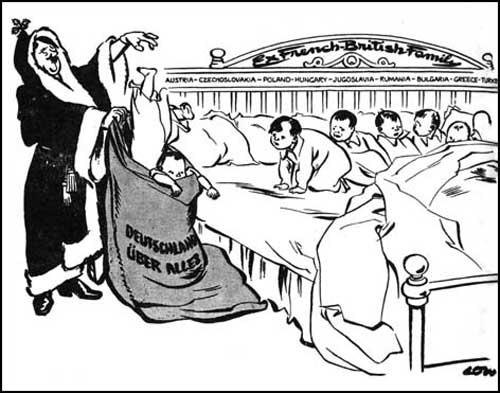

On this day in 1938 the United Kingdom and Poland formed a military alliance in which the UK promised to defend Poland in case of invasion by a foreign power. This took place after the invasion of Czechoslovakia and when it was rumoured that the Nazi-Soviet Pact was about to be signed. Neville Chamberlain believed that this pledge would stop Adolf Hitler ordering the invasion of Poland.

On 31st August, 1939, Hitler gave the order to attack Poland. The following day fifty-seven army divisions, heavily supported by tanks and aircraft, crossed the Polish frontier, in a lightning Blitzkrieg attack. A telegram was sent to Hitler warning of the possibility of war unless he withdrew his troops from Poland. That evening Chamberlain told the House of Commons: "Eighteen months ago in this House I prayed that the responsibility might not fall on me to ask this country to accept the awful arbitration of war. I fear I may not be able to avoid that responsibility".

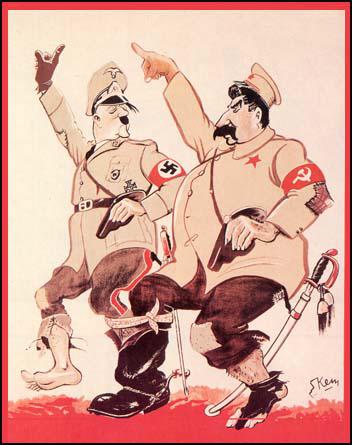

Russian and German Cooperation (1939)

On this day in 1939, Adolf Hitler sent a letter to Neville Chamberlain in which he demanded the Danzig and Polish corridor questions be settled immediately. In return for a settlement, Hitler offered a non-aggression pact to Britain and promised to guarantee the British Empire and to sign a treaty of disarmament. Some appeasers such as Nevile Henderson, Richard Austen Butler and Horace Wilson, wanted to do a deal with Hitler. They were accused by Oliver Harvey of "working like beavers for a Polish Munich".

The reply to Hitler went through several drafts, until it was finally agreed by the whole Cabinet on 28th August. In the letter, Chamberlain suggested direct Polish-German talks to settle the issue peacefully, but would not "acquiesce in a settlement which put in jeopardy the independence of the state to whom they had given their guarantee." (262) In response, Hitler demanded a Polish emissary "with full powers" go to Berlin on 30th August 1939, but the Polish government refused.

On this day in 1948 Whittaker Chambers is interviewed by the House of Un-American Activities Committee. Chambers testified that he had been "a member of the Communist Party and a paid functionary of that party" but left after the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact in August 1939. He explained how the Ware Group's "original purpose" was "not primarily espionage," but "the Communist infiltration of the American government." Chambers claimed his network of spies included Alger Hiss, Harry Dexter White, Lauchlin Currie, Abraham George Silverman, John Abt, Lee Pressman, Nathan Witt, Henry H. Collins and Donald Hiss. Silverman, Collins, Abt, Pressman and Witt all used the Fifth Amendment defence and refused to answer any questions put by the HUAC.

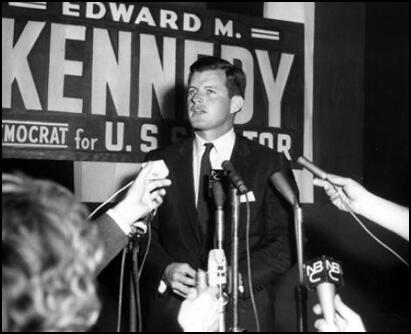

On this day in 2009 politician Edward Kennedy died. Nancy Pelosi, in a statement on Kennedy's death, vowed that a health reform bill would reach the statute book this year. "Ted Kennedy's dream of quality healthcare for all Americans will be made real this year because of his leadership and his inspiration." Marc R. Stanley, chairman of the National Jewish Democratic Council, said: "Kennedy dedicated much of his life to ensuring that affordable healthcare is available for all Americans. The greatest tribute that we can bestow is to thoughtfully, but urgently, enact comprehensive health insurance reform."

Edward (Ted) Kennedy, the youngest son of Joseph Patrick Kennedy and Rose Fitzgerald, was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, on 22nd February, 1932. His great grandfather, Patrick Kennedy, had emigrated from Ireland in 1849 and his grandfathers, Patrick Joseph Kennedy and John Francis Fitzgerald, were important political figures in Boston.

Kennedy later admitted that as the youngest child he was treated with the utmost indulgence by his mother and sisters. He commented in later life that it was like "having a whole army of mothers around me."

Kennedy's father was a highly successful businessman and supporter of the Democratic Party. In 1937 Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him as ambassador to Great Britain. Ted lived in London during this period and by the end of the Second World War when he was 13, he had attended 10 different schools. His eldest brother, Joseph Patrick Kennedy, was killed in action in France in 1944.

In 1950 Kennedy won a place at Harvard University. He was an outstanding sportsman but had difficulty with his academic studies. As one of his biographers has pointed out: "Faced with a Spanish examination he was sure he would fail, Kennedy paid a more adept friend to take it for him. To the chagrin of his family, the plot was discovered and he was expelled, though the incident was covered up for more than a decade. With his exemption from military service now void, he was conscripted into the army from 1951 to 1953. The family appeared to regard his brief service career as a form of punishment and made no effort to ease his lot."

After two years in the US Army Kennedy was allowed to return to Harvard. He got a BA in government in 1956 but failed to qualify for its law school and after a period at the Hague Academy of International Law he enrolled at the University of Virginia. While a student he married the former model, Joan Bennett in 1958.

A member of the Democratic Party Kennedy became involved in politics and in 1958 managed the Senate election campain of his brother, John Fitzgerald Kennedy. He graduated as a bachelor of law in 1959 and was admitted to the Massachusetts bar.

In 1960 Edward Kennedy helped his brother, Robert Kennedy, manage John Kennedy's successful presidential campaign against Richard Nixon. However, as John M. Broder pointed out in the New York Times: "In 1960, when John Kennedy ran for president, Edward was assigned a relatively minor role, rustling up votes in Western states that usually voted Republican. He was so enthusiastic about his task that he rode a bronco at a Montana rodeo and daringly took a ski jump at a winter sports tournament in Wisconsin to impress a crowd. The episodes were evidence of a reckless streak that repeatedly threatened his life and career."

In 1962 Kennedy entered the Senate as a representative of Massachusetts.When his brother was assassinated in 1963 he flew to the family home in Hyannis Port where he had the task of telling his father, Joseph Patrick Kennedy, now frail and bedridden, the news. As Evan Thomas has pointed out: "When the president was assassinated in November 1963, it fell to Teddy to tell their stroke-ridden father. His clumsy wording suggests the pain. There's been a bad accident, Ted began. The president has been hurt very badly. As a matter of fact, he died. Then the son dropped to his knees and wept into the outstretched hands of his father."

On 19th June, 1964, Edward Kennedy was a passenger in a private plane from Washington to Massachusetts that crashed into an apple orchard in bad weather, in the town of Southampton. The pilot and Edward Moss, one of Kennedy's aides, were killed. Kennedy suffered six spinal fractures and two broken ribs. He spent six months in hospital and suffered chronic back pain from the landing for the rest of his life.

Kennedy returned to the Senate in 1965 and along with Robert Kennedy he joined the campaign for the 1965 Voting Rights Act. He tried to strengthen it with an amendment that would have outlawed poll taxes. He lost by only four votes, and showed for the first time his committment to liberal causes.

Initially, Edward Kennedy gave his support to Lyndon B. Johnson when he expanded the U.S. role in the Vietnam War. However, he grew increasingly concerned about the large number of American deaths and after a trip to the country in January 1968 he argued that the president should tell South Vietnam, "Shape up or we're going to ship out." Later he called the war a “monstrous outrage.”

On 16th March, Robert Kennedy declared his candidacy for the presidency, stating, "I am today announcing my candidacy for the presidency of the United States. I do not run for the Presidency merely to oppose any man, but to propose new policies. I run because I am convinced that this country is on a perilous course and because I have such strong feelings about what must be done, and I feel that I'm obliged to do all I can." Edward Kennedy became his brother's leading campaigner.

Soon afterwards Lyndon B. Johnson withdrew from the contest and Robert Kennedy looked certain to be the party's candidate. He had just won his sixth primary in California when he was assassinated. Frank Mankiewicz said of seeing Edward at the hospital where Robert lay mortally wounded: "I have never, ever, nor do I expect ever, to see a face more in grief."

At his brother's funeral, Edward Kennedy gave a speech that included: "Few are willing to brave the disapproval of their fellows, the censure of their colleagues, the wrath of their society. Moral courage is a rarer commodity than bravery in battle or great intelligence. Yet it is the one essential, vital quality for those who seek to change a world that yields most painfully to change." He then went onto quote his brother: "Some men see things as they are and say why. I dream things that never were and say why not."

Edward Kennedy developed a drink problem after the death of Robert Kennedy. One of his biographers has pointed out: "The strain began to show on Kennedy, notably in his increased consumption of alcohol. It surfaced publicly when he went on a Senate fact-finding trip to Alaska the following spring. His staff and the accompanying journalists noticed him taking constant drags from a hip flask on the flights and then searching out bars at each stop. On the homeward flight he repeatedly teetered down the aisle, spilling his drinks on other passengers. He was also having difficulties with his marriage. Like his father and brother John, he had a voracious sexual appetite."

After Richard Nixon was elected in 1968 Edward Kennedy was widely assumed to be the front-runner for the 1972 Democratic nomination. In January 1969, Kennedy was elected as Senate Majority Whip, the youngest person to attain that position. In this role he made determined efforts to stop Nixon's plans to cut back on welfare and other federal programmes for the poor.

On 17th July, 1969, Mary Jo Kopechne joined several other women who had worked for the Kennedy family at the Edgartown Regatta. She stayed at the Katama Shores Motor Inn on the southern tip of Martha's Vineyard. The following day the women travelled across to Chappaquiddick Island. They were joined by Ted Kennedy and that night they held a party at Lawrence Cottage. At the party was Kennedy, Kopechne, Susan Tannenbaum, Maryellen Lyons, Ann Lyons, Rosemary Keough, Esther Newburgh, Joe Gargan, Paul Markham, Charles Tretter, Raymond La Rosa and John Crimmins.

Mary Jo Kopechne and Kennedy left the party at 11.15pm. Kennedy had offered to take Kopechne back to her hotel. He later explained what happened: "I was unfamiliar with the road and turned onto Dyke Road instead of bearing left on Main Street. After proceeding for approximately a half mile on Dyke Road I descended a hill and came upon a narrow bridge. The car went off the side of the bridge.... The car turned over and sank into the water and landed with the roof resting on the bottom. I attempted to open the door and window of the car but have no recollection of how I got out of the car. I came to the surface and then repeatedly dove down to the car in an attempt to see if the passenger was still in the car. I was unsuccessful in the attempt."

Instead of reporting the accident Edward Kennedy returned to the party. According to a statement issued by Kennedy on 25th July, 1969: "instead of looking directly for a telephone number after lying exhausted in the grass for an undetermined time, walked back to the cottage where the party was being held and requested the help of two friends, my cousin Joseph Gargan and Paul Markham, and directed them to return immediately to the scene with me - this was some time after midnight - in order to undertake a new effort to dive."

When this effort to rescue Mary Jo Kopechne ended in failure, Kennedy decided to return to his hotel. As the ferry had shut down for the night Kennedy, swam back to Edgartown. It was not until the following morning that Kennedy reported the accident to the police. By this time the police had found Mary Jo Kopechne's body in Kennedy's car.

Edward Kennedy was found guilty of leaving the scene of the accident and received a suspended two-month jail term and one-year driving ban. That night he appeared on television to explain what had happened. He explained: "My conduct and conversations during the next several hours to the extent that I can remember them make no sense to me at all. Although my doctors informed me that I suffered a cerebral concussion as well as shock, I do not seek to escape responsibility for my actions by placing the blame either on the physical, emotional trauma brought on by the accident or on anyone else. I regard as indefensible the fact that I did not report the accident to the police immediately."

At the inquest Judge James Boyle raised doubts about Kennedy's testimony. He pointed out that as Kennedy had a good knowledge of Chappaquiddick Island he could not understand how he managed to drive down Dyke Road by mistake. For example, on the day of the accident, Kennedy had twice had driven on Dyke Road to go to the beach for a swim. To get to Dyke Road involved a 90-degree turn off a metalled road onto the rough, bumpy dirt-track.

An investigation at the scene of the accident by Raymond R. McHenry, suggested that Kennedy approached the bridge at an estimated 34 miles (55 kilometres) per hour. At around 5 metres (17 feet) from the bridge, Kennedy braked violently. This locked the front wheels. According to McHenry: "The car skidded 5 metres (17 feet) along the road, 8 metres (25 feet) up the humpback bridge, jumped a 14 centimetre barrier, somersaulted through the air for about 10 metres (35 feet) into the water and landed upside-down."

Investigators found it difficult to understand why he was crossing Dyke Bridge when he said he was attempting to reach Edgartown which was in the opposite direction. They also could not understand why he was driving so fast on this unlit, uneven, road. They also could not work out how Kennedy escaped from the car. When it was recovered from the water all the doors were locked. Three of the windows were either open or smashed in. If Kennedy, a large-framed 6 foot 2 inches tall man could manage to get out of the car, why was it impossible for Kopechne, a slender 5 foot 2 inches tall, not do the same?

Local experts could not understand why Kennedy (and later, Markham and Gargan) could not rescue Kopechne from the car. It also surprised investigators that Kennedy did not seek help from Pierre Malm, who only lived 135 metres from the bridge. At the inquest Kennedy was unable to answer this question.

There were also doubts about the way Mary Jo Kopechne died. Dr. Donald Mills of Edgartown, wrote on the death certificate: "death by drowning". However, Gene Frieh, the undertaker, told reporters that death "was due to suffocation rather than drowning". John Farrar, the diver who removed Kopechne from the car, claimed she was "too buoyant to be full of water". It is assumed that she died from drowning, although her parents filed a petition preventing an autopsy.

Other questions were asked about Kennedy's decision to swim back to Edgartown. The 150 metre channel had strong currents and only the strongest of swimmers would have been able to make the journey safely. Also no one saw Kennedy arrive back at the Shiretown Inn in wet clothes. Ross Richards, who had a conversation with Kennedy the following morning at the hotel described him as casual and at ease.

Kennedy did not inform the police of the accident while he was at the hotel. Instead at 9am he joined Gargan and Markham on the ferry back to Chappaquiddick Island. Steve Ewing, the ferry operator, reported Kennedy in a jovial mood. It was only when Kennedy reached the island that he phoned the authorities about the accident that had taken place the previous night.

Dr. Robert Watt, Kennedy's family doctor, explained his patient's strange behaviour by claiming he was in a state of shock and confusion and "possible concussion."

President Richard Nixon told his White House chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman that this was "the end of Teddy" and that it "will be around his neck forever." Max Lerner wrote in Ted and the Kennedy Legend: A Study in Character and Destiny (1980), this self-inflicted wound, more than any other event, "blocked his path to the White House, called his credibility into question and damaged the Kennedy legend."

The Chappaquiddick incident continued to haunt Kennedy and in January 1971, he lost his position as Senate Majority Whip when he was defeated by Senator Robert Byrd, 31–24. Kennedy now concentrated on wider political issues. This included becoming chair of the Senate subcommittee on health care. Over the next few years Edward Kennedy developed a well-deserved reputation in Capitol Hill as a diligent and effective legislator.

As Evan Thomas pointed out in Newsweek: "Edward Kennedy, perhaps more than any United States senator in the past half century, cared about the poor and dispossessed. Though he was relentlessly mocked by the right as a tax-and-spend liberal, he kept the faith.... He was hardly the first rich person to care. Oblige has gone with noblesse for ages; Franklin Roosevelt, creator of the New Deal, was a rich aristocrat. But there was a seriousness, a doggedness, to Kennedy. He was no dilettante, no limousine liberal. He was a prodigious worker, the strongest force in the government for women's rights and health care, civil rights and immigration, the rights of the disabled and education. He was effective: in the Senate, to get something done, you went to Ted Kennedy."

Kennedy was also an outspoken critic of President Richard Nixon. He made several speeches attacking Nixon's policies in Vietnam. He called it "a policy of violence that means more and more war". Kennedy also strongly criticized the Nixon administration's support for Pakistan and its ignoring of "the brutal and systematic repression of East Bengal by the Pakistani army".

However, because of the death of Mary Jo Kopechne, Kennedy was not in a position to obtain the nomination to take on Nixon in the 1972 presidential election. As one commentator has pointed out: "The judge ruled that Kennedy was probably guilty of criminal conduct but made no move to indict him. This obvious manipulation of the local judiciary by the state's most powerful family was probably more damaging in the long term than the tragedy itself."

Edward Kennedy and Joan Bennett Kennedy had three children: Kara Anne (27th February, 1960), Edward Moore Kennedy, Jr. (26th September, 1961) and Patrick Joseph Kennedy (14th July, 1967). The children encountered several health problems. Patrick suffered from severe asthma attacks and in 1973 Edward was discovered to have bone cancer and had to have his right leg amputated. Joan has also had three miscarriages and this contributed to her developing a serious drink problem. In 1978, the couple separated and shortly afterwards she gave an interview to McCall's Magazine where she admitted to being an alcoholic.

In 1979 Kennedy made another attempt to become the Democratic Party presidential candidate when he took on the sitting president, Jimmy Carter, a member of his own party. Kennedy won 10 presidential primaries but he eventually withdrew from the race when it became clear that the public was still concerned about the events on Chappaquiddick Island. When he withdrew from the campaign he made a speech where he argued: "For me, a few hours ago, this campaign came to an end. For all those whose cares have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die."

Edward Kennedy and Joan Bennett Kennedy divorced in 1982. Kennedy easily defeated Republican businessman Ray Shamie to win re-election in 1982. He was already the ranking member of the Labor and Public Welfare Committee but Senate leaders also granted him a seat on the Armed Services Committee. Kennedy now became an outspoken critic of the foreign policy of President Ronald Reagan. This included intervention in the Salvadoran Civil War and the support for the Contras in Nicaragua.

Kennedy also objected to the support President Reagan gave to apartheid government in South Africa. In January 1985 he visited the country and spent a night in the Soweto home of Bishop Desmond Tutu and also visited Winnie Mandela, wife of imprisoned black leader Nelson Mandela. On his return to the United States he campaigned for economic sanctions against South Africa and was mainly responsible for the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986. President Reagan attempted to veto the legislation but was overridden by the United States Congress (by the Senate 78 to 21, the House by 313 to 83). This was the first time in the 20th century that a president had a foreign policy veto overridden. Later that year he travelled to the Soviet Union where he had talks with Mikhail Gorbachev. This led to the release of several political prisoners, including Anatoly Shcharansky.

In 1991, Kennedy was involved in another scandal when his nephew William Kennedy Smith was accused of sexual offences against Patricia Bowman while at a party at the family's Palm Beach, Florida estate. Smith was eventually acquitted and even though he was not directly implicated in the case he issued a public statement about his life: " "I am painfully aware of the disappointment of friends and many others who rely on me to fight the good fight. I recognise my own shortcomings, the faults in the conduct of my private life."

Ted Kennedy met Victoria Reggie, a Washington lawyer at Keck, Mahin & Cate, on 17th June 1991. They were married on 3rd July, 1992, in a civil ceremony at Kennedy's home in McLean, Virginia.

Kennedy remained on the left of the party and has been identified with various progressive causes. He was achairman of the United States Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. In 2007 he helped pass the Fair Minimum Wage Act, which incrementally raises the minimum wage by $2.10 to $7.25 over a two year period. The bill also included higher taxes for many $1 million-plus executives. Kennedy was quoted as saying, "Passing this wage hike represents a small, but necessary step to help lift America's working poor out of the ditches of poverty and onto the road toward economic prosperity."

On May 20, 2008, doctors announced that Kennedy has a malignant brain tumor, diagnosed after he experienced a seizure at Hyannisport. The following month Kennedy underwent brain surgery at Duke University Hospital.

During his last months Kennedy, who was chairman of the Senate health committee, used what energy he had left to try and get the proposal by Barack Obama, to extend insurance coverage to 46 million people. Kennedy described health reform as the "cause of my life". As The Washington Post pointed out: "His measures gave access to care for millions and funded treatment around the world. He was a longtime advocate for universal health care and promoted biomedical research, as well as AIDS research and treatment."