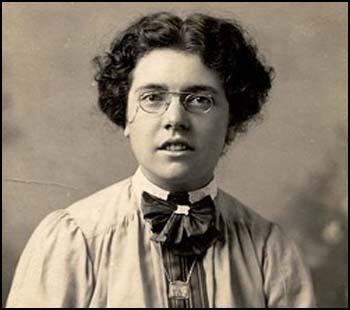

Alice Chapin

Alice Chapin, the daughter of Ephraim Atlas Chapin (1819–1868), a prosperous businessman with railroad interests, and his wife, Josephine Clark Chapin (1825–1888). (1857–1934) was born at Keene, Cheshire County, New Hampshire, USA, on 28th August 1857. After her father's death the family moved to Brooklyn, where her brother Alfred Clark Chapin (1848–1936) practised law, was mayor, and was briefly a Congressman. (1)

Alice Chapin wanted to work in the theatre and chosen, from some 30 or 40 aspirants, to play Juliet in a special performance of Romeo and Juliet, given at the Brooklyn Theatre. After this she become a student at the New York Dramatic College, where she studied with David Belasco. (2)

In 1880 she married Harvey Merrill Ferris, who was in the Brooklyn real estate business, the son of W. Hawkins Ferris of the United States Sub-Treasury. Harold Chapin was born in 1886. The marriage was unhappy, and after a private hearing, she was granted a divorce in June 1888. Reverting to her own name and having been left a considerable fortune by her mother, she moved to England where, an immigrant and a divorcee, she secured her son's education, and had a daughter, Elsie Chapin. (3)

Alice Chapin met the successful Shakespearean actor Hermann Vezin soon after arriving in England. This resulted in her playing Virgilia, the hero's wife in Coriolanus at the Globe Theatre, Miss Capin went on tour as the American widow in Aunt Jack. She then played Minna in Fauntleroy, a play based on Frances Hodgson Burnett's novel, Little Lord Fauntleroy. (4)

Women's Freedom League

In 1908 Alice Chapin joined the Women's Freedom League (WFL). The group had been formed the previous year by seventy members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) who disagreed with the way Emmeline Pankhurst was running the organization. "We are not playing experiments with representative government. We are not a school for teaching women how to use the vote. We are a militant movement... It is not a school for teaching women how to use the vote. We are militant movement... It is after all a voluntary militant movement: those who cannot follow the general must drop out of the ranks." As Simon Webb has pointed out: "This is quite unambiguous. Members must not expect to influence policy or question the leader, the role is limited to obeying orders." (5)

Violet Tillard became Assistant Organising Secretary of the WFL. She was active in promoting women's suffrage in newspapers. In one letter she pointed out the difference between the WFL and the WSPU. "The Women's Freedom League differs from the Women's Social and Political Union chiefly in the internal organisation, which in democratic; and in the fact that it is not part of its policy at present to interrupt Cabinet Ministers at meetings; but the societies at one in their aim the removal of the sex disability, and in their policy of opposing the Government at bye-elections." (6)

Alice Chapin joined the Actresses' Franchise League (AFL). Members included Cicely Hamilton, Elizabeth Robins, Kitty Marion, Winifred Mayo, Sime Seruya, Edith Craig, Inez Bensusan, Ellen Terry, Lillah McCarthy, Sybil Thorndike, Vera Holme, Lena Ashwell, Christabel Marshall, Lily Langtry and Nina Boucicault. The AFL was open to anyone involved in the theatrical profession and its aim was to work for women's enfranchisement by educational methods, selling suffrage literature and staging propaganda plays such as How the Vote was Won, Votes for Women and A Pageant of Great Women. (7)

1909 Bermonsey By-Election

On 28 October 1909 there was a by-election in Bermondsey. A supporter of women's suffrage, Alfred Salter was standing for the Labour Party. However, the Liberal Party had won the seat in the 1906 General Election and after forming the government had refused to give women the vote. Alison Neilans and Alice Chapin of the Women's Freedom League decided to try and invalidate the election. Neilans later recalled that this action "had been running in the minds of members of the League for nearly two years." Chapin added: "The battle of votes for women was one that was going to be fought out to the finish. It was perfectly logical for them to protest at elections and say they would not put up with the tyranny of the present Government." (8)

On the day of the election, Neilans and Chapin attacked polling stations, smashing bottles containing corrosive liquid over ballot boxes, in an attempt to destroy votes. According to a report in the The New York Times, Chapin "broke a bottle of champagne containing corrosive acid on a ballot box with the apparent intention of destroying the ballots which the box contained. The acid, little or none of which found its way into the box, spattered upon election officials, one of whom were badly burned." (9)

The Times claimed that the presiding officer, George Thornley, was blinded in one eye in one of these attacks, and a Liberal agent suffered a severe burn to the neck. The count was delayed while ballot papers were carefully examined, 83 ballot papers were damaged but legible but two ballot papers became undecipherable. Despite the actions of the two women it was decided the election was valid. (10)

Alison Neilans defended her action by claiming: "There had been a great shriek in the Press and elsewhere about vitriol, which was as unjust as it was ridiculous. The tube she carried contained nothing more dangerous than photographic chemicals, which could do no more damage than produce a black stain. The Women's Freedom League never had intended to injure individuals and never would intentionally. The women identified with this movement had never failed yet in anything they had tried to do, and they would not be foiled in the future. They had among them members of the League who were prepared if necessary to do 10 or 15 years in prison for the good of the cause." (11)

At Capin's trial at the Old Bailey, the injured presiding officer, George Thorley, said Chapin raised her band and brought it smartly down on the mouth of the ballot-box. There was a slight crash as of breaking glass, and witness felt the splash on his face and in his eye. He went to Guy's Hospital. His sight, which has been affected, was improving. He added that he "did not believe for a moment that defendant meant to injure his eye". (12)

Alice Chapin was sentenced to seven months' imprisonment. Three months of her punishment being for interfering with a ballot box, and the rest of the term for assault on a polling clerk. Alison Neilans, "who made a similar attempt to express suffragette sentiments at the by-election, but with less serious consequences, was also convicted and was sentenced to three months' imprisonment." (13)

Neilans went on hunger-strike and was forced-fed. "When the doctors entered her cell they had given her the choice of weapons - nasal tube, stomach tube, or feeding-cup. Which did she prefer? Although she heard the stomach-tube operation was the most dangerous, she choose this method in preference to the nasal feeding. She was held down in the chair by two women, their fingers were forced between her teeth, her head thrown back, the tube was gradually forced down her throat, and the feeding commenced. Although she did not go so far as to describe the operation as torture, she did say it was the most unspeakable outrage that could be offered to anyone." (14)

First World War

Most members of the Women's Freedom League, were pacifists, and so when the First World War was declared in 1914 they refused to become involved in the British Army's recruitment campaign. The WFL also disagreed with the decision of the NUWSS and WSPU to call off the women's suffrage campaign while the war was on. Leaders of the WFL such as Charlotte Despard believed that the British government did not do enough to bring an end to the war and between 1914-1918 supported the campaign of the Women's Peace Crusade for a negotiated peace. The Vote attacked Christabel Pankhurst and Millicent Garrett Fawcett, for condemning the women's peace conference. (15)

By this time Alice's son, Harold Chapin, was a highly successful actor and writer. In September 1912, his four-act play Elaine, written while he was in Glasgow, was performed at the Gaiety Theatre. The play was directed by Lewis Casson and produced by Annie Horniman. Casson's wife, Sybil Thorndike played the lead role. According to Jonathan Croall, the author of Sybil Thorndike: A Star of Life (2008), the play was a "witty, gently satirical comedy about attitudes to love and money in marriage." This was a prolific period for Chapin. The Dumb and the Blind had a long run at the Prince of Wales (1912-13). William Archer described it as "a veritable masterpiece in its way - a thing Dickens would have delighted in. There is not a single false note in the little play: it is as restrained as it is touching." (16)

Although an American citizen, on 2nd September 1914 he enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps. Chapin was sent to St. Albans where he met up with Lewis Casson, the man who directed several of his plays and had appeared with him several times on the stage. Chapin was initially given the job in the Cook House. He wrote to his wife, Calypso Valetta: "We are being sorted into jobs. I fancy I shall stay on cooking. This is good because it is as useful a job as is going and one that demands conscientious hard work still it does not involve going into the actual firing line - a thing I have no ambition to do. Stray shell fire and epidemics are all I want to face thank you, let those who like the firing line have all the bullets they want." (17)

Harold Chapin wrote to his mother on 1st June, 1915: "By the way, let me assure you of one thing. I am taking the greatest care of myself - no collecting souvenirs under fire for me. I am not particularly nervous - in fact I have not yet been badly frightened, but I have been struck cautious - if you know what I mean - every time I have been anywhere where caution was necessary. I do not even share the rather popular (with the infants) desire for a slight wound 'just enough to get you a fortnight at home.' I want to stick the war out usefully and unostentatiously - but, oh, I hope it'll end this year. It will - or not - just according to the energy concentrated by you people at home on the one job of piling up shells, guns, clothes, food, men, bombs, motors, horses, and delivering them to the right spot at the right moment. Oh, and you can devote some energy too to inventing a gas ten times as beastly as the German product and a means of projecting it four times as far." (18)

Chapin quickly became aware that the realities of trench-warfare meant that the war would continue for some time. He shared the views of General Douglas Haig that the conflict could only be won by war of attrition. "If you at home could only see and hear the enormous concentration of force necessary to take a mile of German trench; the terrific resistance we have to put up to hold it; the price we have to pay over every little failure - a price paid with no purchase to show for it - if you could only see and realize these things there'd be some hope of you all bucking in and supplying the little extra force - the little added support in resistance - that we need to end this murderous, back and forth business." (19)

Harold Chapin was killed on Sunday, 26th September, at the battle of Loos. A fellow soldier, Richard Capell, wrote to his wife about what happened: "Our line that afternoon wavered for a moment, before the counter-attack. There was a short period of confusion, and some of our men were caught in the open by German rifle and machine-gun fire. You may possibly one day get an exact account from an actual eye-witness, but from what I can piece together, your husband went over the parapet to fetch in some wounded man. He was certainly shot in the foot. It appears that he persisted and was then killed outright by a shot through the head." (20)

The loss of Harold Chapin's talent has been compared to the death of Rupert Brooke. In December 1915, at the Queen's Theatre, London, Calypso and Alice Chapin appeared alongside Gerald du Maurier and Sydney Fairbrother in a memorial performance of four of his one-act plays to raise funds for a YMCA hut at the front. (21)

Return to the United States

Alice Chapin returned to the United States in 1916, and settled in New York City. She continued to perform both on stage and in film, including Thais (1917), The Spreading Dawn (1917), By Hook or Crook (1918), Anne of Little Smoky (1921), Icebound (1924), Daughters of the Night (1924), Manhattan (1924), Argentine Love (1924), Youth for Sale (1924), The Crowded Hour (1925) and Pearl of Love (1925).

Alice Chapin died at the Elliot Community Hospital, Keene, New Hampshire, on 5th July 1934, following a fall. (22)

Primary Sources

(1) The Era (26th May 1906)

Miss Alice Chapin hails from New England and is descended from the old Puritan stock. There was strong opposition when she announced her determination to become an actress, but "where there's a will there's a way," and when her family removed to Brooklyn, New York, Miss Chapin became so popular as an amateur performer that she was chosen, from some 30 or 40 aspirants, to play Juliet in a special performance of Romeo and Juliet, given at the Brooklyn Theatre. Her next step was to become a student at the New York Dramatic College, where she had the inestimable advantage of studying with David Belasco.

Shortly after leaving the college Miss Chapin came to England, so that practically all her experience has been gained in this country. Mr. Herman Vezin gave the stranger a hearing welcome upon her arrival on these shores, and Miss Chapin has most grateful recollections of cosy chats, interspersed with Shakespearean reading, in his delightful little flat, while Mr. Vezin dispensed tea and good advice with strict impartiality. After a first appearance as Virginia at a matinee at the Globe Theatre, Miss Capin went on tour as the American widow in Aunt Jack. A short engagement to play Minna in Fauntleroy followed. Last summer Miss Chapin again resumed acquaintance with this play, but this time she played "Dearest" to her little daughter's Cedric.

(2) The Leicester Daily Post (1st November 1909)

Miss Neilans said the more they made at Bermondsey had been running in the minds of members of the League for nearly two years. There had been a great shriek in the Press and elsewhere about vitriol, which was as unjust as it was ridiculous. The tube she carried contained nothing more dangerous than photographic chemicals, which could do no more damage than produce a black stain. The Women's Freedom League never had intended to injure individuals and never would intentionally. The women identified with this movement had never failed yet in anything they had tried to do, and they would not be foiled in the future. They had among them members of the League who were prepared if necessary to do 10 or 15 years in prison for the good of the cause.

Mrs Chapin, who on rising was received with loud applause, then proceeding to deal with the part she played at Bermondsey on the polling day. She was, she said, very far from being a war like character: in fact, she was too much of a dreamer to hanker after active service at all. But the battle of votes for women was one that was going to be fought out to the finish. It was perfectly logical for them to protest at elections and say they would not put up with the tyranny of the present Government.

Mrs How Martyn announced that she had received a letter from Mr Baker, solicitor to the League, who expressed the opinion that for the first time members of the League had committed an indictable offence which could not be dealt with at the police court, so that it would have to go for trial. She went on to say that in one respect they made a mistake over Bermondsey. They had thought that if they succeeded in spoiling one voting paper it would inviolate the election. They know better now.

(3) The New York Times (5th November, 1909)

Mrs Chapin, the militant Suffragette who made an attack on a polling place during the Bermondsey by-election last Thursday, was committed for trial by the Magistrate at the Old Baily today, and the double change of unlawfully meddling with the ballot box and causing grievous harm to the presiding officer.

Mrs Chapin broke a bottle of champagne containing corrosive acid on a ballot box with the apparent intention of destroying the ballots which the box contained. The acid, little or none of which found its way into the box, spattered upon election officials, one of whom were badly burned.

Miss Alison Neilans was also committed for trial charged with a similar attempt to destroy ballots in another booth at the same election.

(4) Dundee Evening Telegraph (24th November 1909)

At the Old Bailey today, Alice Chapin (45) was indicted for unlawfully interfering with the ballot-box during the Bermondsey election by introducing divers liquid chemicals into it for attempting to destroy the ballot papers and for assaulting George Thorley.

Accused pleaded not guilty.

Counsel said defendant threw a chemical liquid into the ballot-box, and 80 ballot papers were nearly destroyed. Some of the liquid splashed on to Mr Thorley's face, that gentlemen being the presiding officer. One of Mr Thorley's eyes were injured.

Mr. George Thorley said Chapin raised her band and brought it smartly down on the mouth of the ballot-box. There was a slight crash as of breaking glass, and witness felt the splash on his face and in his eye. He went to Guy's Hospital. His sight, which has been affected, was improving.

Cross-examined – witness did not believe for a moment that defendant meant to injure his eye.

Further evidence was given that all the papers affected were deciphered.

Mrs. Chapin was found guilty of interfering with the ballot-box and of common assault.

Sentence was postponed until the conclusion of the trial of Miss Nielans in connection with the Bermondsey incidents, which is now proceeding.

(5) The New York Times (25th November, 1909)

Mrs Alice Chapin, the militant suffragette, who injured a polling clerk at the Bermonsey by-election when she smashed a bottle containing corrosive acid on a ballot box was sentenced in the Old Bailey Court today to seven months' imprisonment. She was convicted on the charges, three months of her punishment being for interfering with a ballot box, and the rest of the term for assault on a polling clerk.

Miss Alison Neilans, who made a similar attempt to express suffragette sentiments at the by-election, but with less serious consequences, was also convicted and was sentenced to three months' imprisonment.

(6) The Vote (12th February 1910)

Alison Neilans who was sentenced to three months' imprisonment in connection with the Bermondsey ballot-box, was released from Holloway. Three months in that school for women politicians, learning the working of man-made law under conditions which have aroused the just indignation of every civilised country, would, we thought, have sent her back to us broken in body, but not in spirit…

There is no poetry in the early morning – only grim reality; and the crowd of us who watched for the gate to open were not a little sad and not a little dispirited. And it was our prisoner who cheered us up. The gates open at last, and swinging down the yard came Alison, a little thinner but brave and young and dauntless, with the light of battle in her eyes. "I'm keener than ever," was her greeting; and, drawing us across the road, she led our shouts of greeting to Mrs. Chapin, who still remained in the black castle of North London…

Proceeding, Miss Neilans said that in undergoing this term of imprisonment she had only done what any women, given the opportunity, would do if she had this cause at heart… After this, her third and longest term of imprisonment, Mrs Neilans said that she had absolutely the same opinion of the Rt. Hon. (Coward) Gladstone as before she went in, but the officers in Holloway Prison had shown her as much kindness as lay in their power….

After forty-eight hours without food the Governor had come to her and said: "You have now been forty-eight hours without food, so I must have you fed tonight if you do not give in."

When the doctors entered her cell they had given her the choice of weapons – nasal tube, stomach tube, or feeding-cup. Which did she prefer? Although she heard the stomach-tube operation was the most dangerous, she choose this method in preference to the nasal feeding.

She was held down in the chair by two women, their fingers were forced between her teeth, her head thrown back, the tube was gradually forced down her throat, and the feeding commenced. Although she did not go so far as to describe the operation as torture, she did say it was the most unspeakable outrage that could be offered to anyone.

(7) The New York Times (7th July, 1934)

Mrs. Alice Chapin, 76 years old, actress who played in many theatres in this country and in England, died yesterday of injuries suffered in a fall on May 9. She leaves a brother, Alfred Chapin, former Mayor of Brooklyn, and a grandson, Harold Chapin of London.