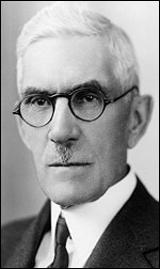

Francis Townsend

Francis Townsend, the second of six children, was born in Fairbury, Illinois, on 13th January, 1867. The son of a farmer, when he was a child the family moved to Nebraska where he had two years of rudimentary high school education in a Congregational academy. After leaving school Townsend worked as a farm labourer in Kansas and Colorado.

In 1887 he borrowed $1,000 from his father and moved to California to develop a hay farming business. The venture was not a success and he enrolled in Omaha Medical College. "The oldest in his class at thirty-one years, he supported himself in part with a newspaper route and was taken under the wing of an instructor who was also an ardent socialist." (1)

After graduating, Townsend worked as a doctor in Belle Fourche, South Dakota, a cattle town, where he treated the ailments of cowboys, miners and prostitutes. He met a widow Wilhelmina Bogue, who was a nurse and she soon became his wife. Townsend wrote for the local newspaper and served on the town council. His progressive views on politics resulted in him being forced to leave the town.

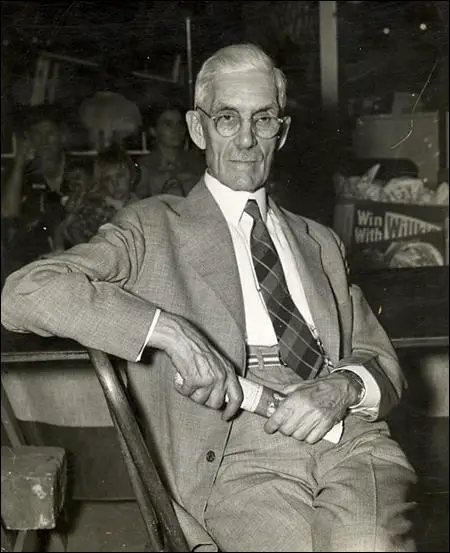

Dr. Francis Townsend

During the First World War he joined the Army Medical Corps as a doctor. He served on the Western Front and had to deal with the influenza epidemic at the end of the conflict. On his return to he moved to Long Beach to run a dry ice factory. When that business failed he became an estate agent. After the Wall Street Crash and the Great Depression, he found work as a public health officer "where he witnessed first-hand the effects of poverty on the aged." In June, 1933, he lost his job and his wife returned to nursing to support them. (2)

William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), has argued: "He (Francis Townsend) was sixty-seven years old, and had less than a hundred dollars in savings. Disturbed not only by his own plight but by that of others like him - elderly people from Iowa and Kansas who had gone west in the 1920's and now faced the void of unemployment with slim resources." (3)

The Townsend Plan

In 1933 Townsend and Robert Earl Clements, a real estate promoter, proposed a scheme whereby the Federal government would provide every person over 60 a $200 monthly pension (roughly $2,600 in today's money), on condition that he or she retire from all gainful work and spent the money in the United States. Townsend claimed that his Old Age Revolving Pension Plan could be financed by a 2 per cent tax on business transactions. Townsend argued that his plan would help the economy as older people would be compelled to surrender their positions to the younger unemployed and the spending of the pension money would produce a demand for goods and services that would create still more jobs. (4)

Some critics described Townsend's plans as being an example of the ideas of the "crackpot Left". (5) Other observers pointed out that it was far from radical and appealed to Protestant rural America and proclaimed traditional values, and promised to preserve the profit system free from alien collectivism, socialism and communism. In the words of Townsend, the movement embraced people "who believe in the Bible, believe in God, cheer when the flag passes by, the Bible Belt solid Americans." He told his followers: "The movement is yours, my friends... Without you I am powerless but with you I can remake the world for mankind." (6)

Walter Lippmann observed: "If Dr. Townsend's medicine were a good remedy, the more people the country could find to support in idleness the better off it would be." Townsend replied "My plan is too simple to be comprehended by great minds like Mr. Lippmann's." (7) One historian has pointed out that "Townsend meetings featured frequent denunciations of cigarettes, lipstick, necking, and other signs of urban depravity. Townsendites claimed as one of the main virtues of the plan that it would put young people to work and stop them from spending their time in profligate pursuit of sex and liquor." (8)

Townsend plan would have diverted 40 per cent of the national income to 9 per cent of the people. It obtained a great deal of public support and by 1935 his Townsend Club had over 5 million members. Most of them from among otherwise conservative people, that politicians throughout the country had to take these ideas into consideration. The pressure increased when Townsend handed in to President Franklin D. Roosevelt a petition supporting the Old Age Revolving Pension Plan that had been signed by over 20 million people. (9)

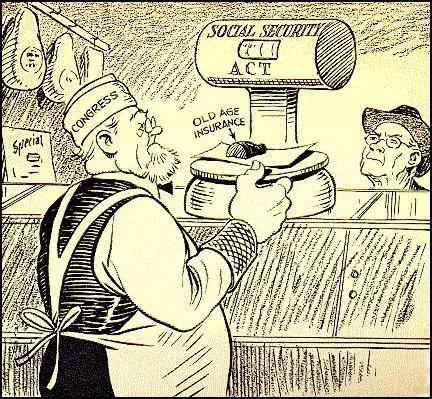

Social Security Act

Frances Perkins, one of Roosevelt's most senior colleagues, later recalled in her autobiography, The Roosevelt I Knew (1946): "One hardly realizes nowadays how strong was the sentiment in favour of the Townsend Plan and other exotic schemes for giving the aged a weekly income. In some districts the Townsend Plan was the chief political issue, and men supporting it were elected to Congress. The pressure from its advocates was intense." (10)

The measures taken by President Roosevelt did help 2 million people to find jobs by 1934 but unemployment remained high at 11.3%. The nation's GDP registered a 17% increase on 1933 but national income was still little better than half of what it had been in 1929. Roosevelt and the Democrats were worried about the outcome of the mid-term elections in November, 1934. However, they were wrong to be concerned as the government was rewarded for its actions to deal with the country's economic problems. In the House of Representatives the Democratic majority increased from 310 to 322 and in the Senate they now held 69 seats that was more than a two-thirds majority. Never in the history of the Republican Party had its percentage in either House been so low. Arthur Krock wrote in the The New York Times that the New Deal had won "the most overwhelming victory in the history of American politics". (11)

These results gave President Roosevelt to introduce more radical policies. On 17th January, 1935, Roosevelt asked Congress to pass social security legislation. The two men he chose to guide this measure through Congress had both experienced poverty. Robert Wagner (Senate) was an immigrant boy who had sold newspapers on the street and David John Lewis (House of Representatives) had gone to work at nine in a coal mine. (12)

Roosevelt told the American people: "We must begin now to make provision for the future. That is why our social security program is an important part of the complete picture. It proposes, by means of old age pensions, to help those who have reached the age of retirement to give up their jobs and thus give to the younger generation greater opportunities for work and to give to all a feeling of security as they look toward old age. The unemployment insurance part of the legislation will not only help to guard the individual in future periods of lay-off against dependence upon relief, but it will, by sustaining purchasing power, cushion the shock of economic distress. Another helpful feature of unemployment insurance is the incentive it will give to employers to plan more carefully in order that unemployment may be prevented by the stabilizing of employment itself. (13)

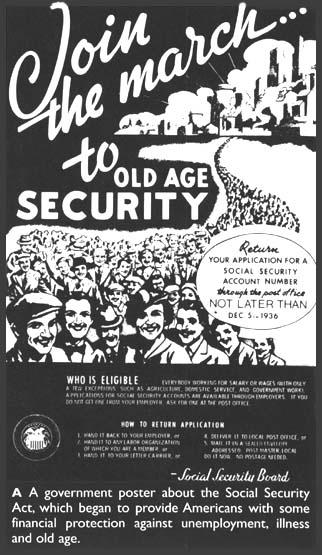

The Social Security Act established Old Age and Survivors' Insurance that provided for compulsory savings for wage earners so that benefits may be paid to them on retirement at 65. To finance the scheme, both the employer and employee had to pay a 3% payroll tax. The provisions of the act also encouraged states to deal with social problems. It did this by offering substantial financial help the states provide unemployment benefits, old-age pensions, aid to the disabled, maternity care, public health work and vocational rehabilitation. (14)

In the debate in Congress, Arthur Harry Moore protested that if the legislation was passed: "It would take all the romance out of life. We might as well take a child from the nursery, give him a nurse, and protect him from every experience that life affords." Newspapers were also hostile to these measures. For example, The Jackson Daily News reported: "The average Mississippian can't imagine himself chipping in to pay pensions for able-bodied Negroes to sit around in idleness on front galleries, supporting all their kinfolks on pensions, while cotton and corn crops are crying for workers to get them out of the grass." (15)

After being passed by Congress in April and signed into law by President Roosevelt on 14th August, 1935. William E. Leuchtenburg has argued: "In many respects, the law was an astonishingly inept and conservative piece of legislation. In no other welfare system in the world did the state shirk all responsibility for old-age indigency and insist that funds be taken out of the current earnings of workers. By relying on regressive taxation and withdrawing vast sums to build up reserves, the act did untold economic mischief. The law denied coverage to numerous classes of workers, including those who needed security most: notably farm laborers and domestics. Sickness, in normal times the main cause of joblessness, was disregarded. The act not only failed to set up a national system of unemployment compensation but did not even provide adequate national standard." (16)

Despite its faults the Social Security Act of 1935 was a new landmark in American history. It reversed historic assumptions about the nature of social responsibility, and it established the proposition that the individual had the same social rights as those people living in Europe. Roosevelt defended his decision to make the employee contributions so high: "We put those payroll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their pensions and their unemployment benefits. With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever scrap my social security program." (17)

Roosevelt told Anne O'Hare McCormick: "In five years I think we have caught up twenty years. If liberal government continues over another ten years we ought to be contemporary somewhere in the late Nineteen Forties." (18) The British journalist, Henry N. Brailsford, argued that Roosevelt was doing what David Lloyd George had done between 1906 and 1914, but at a quicker tempo. According to William E. Leuchtenburg: "The British reforms, which rested on the conviction that the profit system was compatible with aid to the underdog, had rendered working-class life less precarious and was one of the important reasons that the depression struck Britain less heavily than America." (19)

This reform came under attack from right-wing conservatives. John T. Flynn argued: "Does anyone imagine that $8 a week is security for anyone, particularly since Roosevelt's inflation has cut the value of that in half? But what of the millions of people who through long years of thrift and saving have been providing their own security? What of the millions who have been scratching for years to pay for their life insurance and annuities, putting money in savings banks, commercial banks, buying government and corporation bonds to protect themselves in their old age? What of the millions of teachers, police, firemen, civil employees of states and cities and the government, of the armed services and the army of men and women entitled to retirement funds from private corporations railroads, industrial and commercial? These thrifty people have seen onehalf of their retirement benefits wiped out by the Roosevelt inflation that has cut the purchasing power of the dollar in two. Roosevelt struck the most terrible blow at the security of the masses of the people while posing as the generous donor of security for all." (20)

Growth of Townsend Clubs

Francis Townsend claimed that Roosevelt's social security legislation was completely inadequate and left millions of elderly unprotected. He continued to recruit people to his organization. In November, 1935, Verner Wright Main, the only candidate to support the Townsend Plan in a field of five, won the Republican primary in Mitchigan's Third Congressional District with 13,419 votes; his nearest opponent polled only 4,806 votes. Main went on to defeat his Democratic opponent in the by-election in December. (21)

In the last quarter of 1935 the Townsend Plan national headquarters received $350,000, about twice as much as the previous quarter. By December, 1935 the number of Townsend Clubs reached 5,000, with a total membership of over one million. The circulation of the Townsend National Weekly was close to 250,000 and was making large profits for the organisation. (22)

Some politicians began to fear the growing power of Townsend. On 29th January, 1936, Charles Jasper Bell, a Democratic candidate from Kansas City called for an investigation of the Townsend Plan organisation: "Several groups of fraudulent promoters are enriching themselves by working the so-called pension racket... The promotional activities... falsely and cruelly deluding should be unmasked." (23)

A special committee to investigate Townsend was established in February, 1936. It included Bell, Clare Hoffman, John H. Tolan, Samuel LaFort Collins, Scott Lucas, Joseph Gavagan, John Hollister and John William Ditter. The following month, Townsend's partner, Robert Earl Clements, decided to resign. It was revealed that he sold his share in the company that had been publishing its newspaper for $50,000. According to William E. Leuchtenburg: "The Townsend strength had never been as great as western politicians had been scared into believing, and, with the adroit Clements gone, the political organization fell apart." (24)

The investigation discovered that the organisation had raised over a million dollars, with Townsend taking out a salary of $12,000 in the past 12 months. Pierre Tomlinson, the Townsend Plan's head organizer in its first year, testified that Townsend had told him that he would make "handfuls" of money from the scheme. When Townsend testified on 19th May he became angry by the questions and after "announcing he would return only under arrest, Townsend strode out of the committee room." Townsend was prosecuted by the U.S. Department of Justice for contempt of Congress. However, President Franklin D. Roosevelt commuted Townsend's 30-day prison sentence. Edwin Amenta pointed out: "Roosevelt had no need of an old-age martyr in an election year". (25)

In 1936 Francis Townsend joined with Father Edward Coughlin and Gerald L. K. Smith to form the National Union of Social Justice. They selected William Lepke as their presidential candidate. However, Townsend fell out with Smith and denounced him for his fascist sympathies. Coughlin responded by calling the Townsend Plan "economic insanity". Townsend told his followers that if they should vote for either Lepke or Alfred Landon, the Republican candidate. (26)

In the 1936 Presidential Election Townsend gave endorsements to individual candidates and because of his hostility to Roosevelt he refused to give his support to any Democrats. (27) Roosevelt's obtained one of the greatest election victories in American history. Roosevelt won by 27,751,612 votes to 16,681,913 and carried the electoral college 523 to 8. He won every state but Maine and Vermont. Lepke won only 882,479 votes. The Democratic majority rose to 242 in the House of Representatives and 60 in the Senate and Townsend's views on social security were now totally rejected. (28)

After the presidential election support for the Townsend Plan declined rapidly. When he continued to attack Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Democrats. He upset a lot of his followers when he agreed with the Supreme Court wiped out the National Industrial Recovery Act and Agricultural Adjustment Act. On 2nd February, 1937, Roosevelt made a speech attacking the Supreme Court for its actions over New Deal legislation. He pointed out that seven of the nine judges (Charles Hughes, Willis Van Devanter, George Sutherland, Harlan Stone, Owen Roberts, Benjamin Cardozo and Pierce Butler) had been appointed by Republican presidents. Roosevelt had just won re-election by 10,000,000 votes and resented the fact that the justices could veto legislation that clearly had the support of the vast majority of the public. Roosevelt suggested that the age was a major problem as six of the judges were over 70. Roosevelt announced that he was going to ask Congress to pass a bill enabling the president to expand the Supreme Court by adding one new judge, up to a maximum off six, for every current judge over the age of 70. (29)

Townsend was now seen as a opponent of the New Deal. He now lost the support of most of the leading figures in the movement. The vice-president and twelve officials at national headquarters resigned. The editor and most of the staff of the Townsend National Weekly left their jobs in protest against Townsend's comments. Those who left issued a statement claiming that Townsend "was abusing the trust placed in him by the Townsendites, who had signed on to an organisation devoted to the pension-recovery program." In return, Townsend denounced them all as "self-serving traitors." Townsend's organisation continued for several more years but it no longer had any political impact on the American government. (30)

Francis Townsend died in Los Angeles on 1st September, 1960.

Primary Sources

(1) Franklin D. Roosevelt, radio broadcast, Fireside Chat (28th April, 1935)

While our present and projected expenditures for work relief are wholly within the reasonable limits of our national credit resources, it is obvious that we cannot continue to create governmental deficits for that purpose year after year. We must begin now to make provision for the future. That is why our social security program is an important part of the complete picture. It proposes, by means of old age pensions, to help those who have reached the age of retirement to give up their jobs and thus give to the younger generation greater opportunities for work and to give to all a feeling of security as they look toward old age.

The unemployment insurance part of the legislation will not only help to guard the individual in future periods of lay-off against dependence upon relief, but it will, by sustaining purchasing power, cushion the shock of economic distress. Another helpful feature of unemployment insurance is the incentive it will give to employers to plan more carefully in order that unemployment may be prevented by the stabilizing of employment itself.

(2) William E. Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963)

The Social Security Act created a national system of old-age insurance in which most employees were compelled to participate. At the age of sixty-five, workers would receive retirement annuities financed by taxes on their wages and their employer's payroll; the benefits would vary in proportion to how much they had earned. In addition, the federal government offered to share equally with the states the care of destitute persons over sixty-five who would not be able to take part in the old-age insurance system. The act also set up a federal-state system of unemployment insurance, and provided national aid to the states, on a matching basis, for care of dependent mothers and children, the crippled, and the blind, and for public health services.

In many respects, the law was an astonishingly inept and conservative piece of legislation. In no other welfare system in the world did the state shirk all responsibility for old-age indigency and insist that funds be taken out of the current earnings of workers. By relying on regressive taxation and withdrawing vast sums to build up reserves, the act did untold economic mischief. The law denied coverage to numerous classes of workers, including those who needed security most: notably farm laborers and domestics. Sickness, in normal times the main cause of joblessness, was disregarded. The act not only failed to set up a national system of unemployment compensation but did not even provide adequate national standard.

(3) John T. Flynn, The Roosevelt Myth (1944)

The most tragic illusion about this man is that built up by the ceaseless repetition of the false statement that he gave us a system of security.

Security for whom? For the aged? An oldage security bill was passed during his first administration which provides for workers who reach the age of 65 a pension of $8 a week at most. And even this meager and still very badly constructed plan had to be pushed through against a strange inertness on his part. Roosevelt's mind ran in curious circles. People have forgotten his procrastination about putting through the social security bill until in the 1934 congressional elections the Republicans denounced him for his tardiness. It is difficult to believe this now after all the propaganda that has washed over people's minds. And when he did finally consent to a bill, like so many good ideas that went into his mind, it came out badly twisted. It contained a plan for building a huge reserve fund that would have amounted to nothing more than a scheme to extract billions from the workers' payrolls without any adequate return. Over the protest of the President, the Congress finally took that incredible joker out of the law. But it is in every respect a pathetically inadequate law. Does anyone imagine that $8 a week is security for anyone, particularly since Roosevelt's inflation has cut the value of that in half?

But what of the millions of people who through long years of thrift and saving have been providing their own security? What of the millions who have been scratching for years to pay for their life insurance and annuities, putting money in savings banks, commercial banks, buying government and corporation bonds to protect themselves in their old age? What of the millions of teachers, police, firemen, civil employees of states and cities and the government, of the armed services and the army of men and women entitled to retirement funds from private corporations railroads, industrial and commercial? These thrifty people have seen onehalf of their retirement benefits wiped out by the Roosevelt inflation that has cut the purchasing power of the dollar in two. Roosevelt struck the most terrible blow at the security of the masses of the people while posing as the generous donor of "security for all." During the war boom and in the postwar boom created by spending 40 billion dollars a year the illusion of security is sustained. The full measure of Roosevelt's hopeless misunderstanding of this subject will come when security will be most needed and most absent.

Student Activities

Economic Prosperity in the United States: 1919-1929 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the United States in the 1920s (Answer Commentary)

Volstead Act and Prohibition (Answer Commentary)

The Ku Klux Klan (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject