John Marshall

John Marshall, the son of Jeremiah Marshall, a linen draper from Leeds, and Mary Cowper, was born in Rawdon in 1765. Jeremiah had been a Baptist but by the time John was born he had become a Unitarian and attended the same chapel as Joseph Priestley.

Mary's first two sons died in infancy, and when John fell seriously ill when he was five years old, it was decided that it would be safer if he went to live with an aunt, Sarah Booth, in the village of Rawdon. After being educated at the local school until the age of eleven, John attended Hipperholme School in Halifax.

John joined the family business when he was seventeen. Five years later, Jeremiah Marshall died from a stroke and John became the controlling partner in the company. He also inherited a new house, warehouse and £7,500 in cash.

A few months before his father died, Marshall heard that two men in Darlington, John Kendrew, a glass-grinder, and Thomas Porthouse, a watchmaker, had registered a patent for a new flax-spinning machine. Marshall visited the men and purchased from them the right to make copies of their invention.

After obtaining two partners, Samuel Fenton, a Unitarian draper, and Ralph Dearlove, a linen merchant, Marshall leased Scotland Mill near Leeds. Early in 1788, Marshall, Fenton and Company, began spinning flax yarns. At first the machines did not perform well. Breakages frequently occurred and the yarn came out lumpy and hairy.

Although Marshall had little technical experience, he spent the next two years trying to improve its performance. He made little progress until he recruited a talented engineer, Matthew Murray, to help him. By 1790 the two men had created an efficient flax-spinning machine that produced good quality yarn.

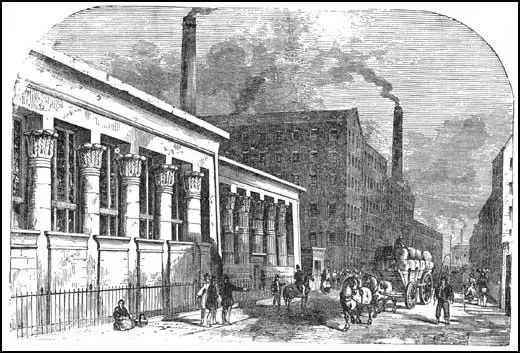

In 1790 Marshall terminated his lease at Scotland Mill and paid William Nayor £600 for an acre of freehold land at Water Lane in Holbeck. Just outside Leeds, the site had distinct advantages over Scotland Mill. Transport problems were solved by the Aire Navigation and the Liverpool Canal. Recruiting labour was also made easier as Holbeck and Leeds had a population of over 36,000 people.

By the time Marshall had built Temple Mill, installed a 20 horse-power Boulton & Watt steam-engine, twenty-eight handlooms, fourteen spinning frames and fourteen carding engines, Marshall, Fenton and Company had an overdraft of £3,783. However, trade was good and by 1793 the 200 workers at the mill were annually producing 85 tons of cloth for sale.

Despite the increasing trade, the heavy investment in machinery had prevented any profits being made. Samuel Fenton and Ralph Dearlove, unconvinced that the venture would ever be profitable, left the partnership. Marshall talked to merchant friends who attended Mill Hill Unitarian Chapel, and managed to persuade two brothers, Benjamin and Thomas Benyon, to invest money in the venture.

Between 1793 and 1800 Marshall's business grew rapidly. Marshall and his partners purchased a new mill at Castle Foregate on which they spent £17,000 in buildings and equipment. Marshall did not find it easy working with the Benyon brothers and in 1804 he had enough capital to buy them out.

Employees at Temple Mill and Castle Foregate worked a 72 hour week. Two-fifths of the people employed by Marshall were young women aged between thirteen and twenty and about one fifth were under thirteen. Marshall treated his workers better than most factory owners. Overseers were forbidden to use corporal punishment to control the workers. Marshall also installed fans and attempted to regulate the temperature of the mill.

Between 1803 and 1815 both Temple Mill (£238,000) and Castle Foregate (£82,000) made healthy profits. By 1820 Marshall was worth over £400,000. Leaving his sons to run the business, Marshall began to take an interest in social problems. He believed that the only way "to promote the improvement of the rising generation was through education". In 1822 he persuaded the owners of several other firms in Holbeck to join him in establishing a school in the area.

During the day children were taught to read and write. Girls also learnt to sew and boys did a course in accounting. Evening classes were held for the older children who worked during the day in the mills. The charge was 3d. a week, or 2d. if they brought their own candle. The teaching methods used at the school were based on those popularized by Joseph Lancaster. Under this system one master taught a select group of older pupils, the monitors, and these in turn taught the rest.

In May 1825, John Marshall began sending children from his mills to day school. At first he selected thirty children aged between eleven and twelve, who he believed would most benefit from schooling. Soon the number had increased to sixty and fifty more of the older children were educated free every Monday evening. Overseers were instructed to send only those who were "well-behaved and wanted to go".

Marshall was also involved in the founding of a Mechanics' Institute and an Literary and Philosophical Society in Leeds. In 1826 he also began a campaign to establish a university in the town. Marshall gave money to the Leeds Library and with Peter Garforth and a small group of Unitarians, helped to re-establish the Leeds Mercury under the editorship of Edward Baines.

In 1826 Marshall decided he wanted to become an MP. He agreed to pay £4,500 for the rotten borough of Rye, but when this deal fell through, he purchased Petersfield for 5000 guineas. Soon after entering the House of Commons in 1827 Marshall became seriously ill. Marshall failed to recover his health and in 1830 decided to leave Parliament and retired to his home in the Lake District.

John Marshall died in 1845.

Primary Sources

(1) John Marshall, Autobiography (unpublished)

My attention was accidentally turned to spinning of flax by machinery, it being a thing much wished for by the linen manufacturers. The immense profits which had been made by cotton spinning had attracted general attention to mechanical improvements and it might be hoped that flax spinning, if practicable, would be equally advantageous. It would be a new business, where there would be few competitors, and was much wanted for the linen manufacture of this country.

(2) William Brown, Flax Spinning in Leeds (1821)

To a person wishing to be conversant in flax spinning the investigation of Marshall's works could not fail to be useful and interesting. These works are the most extensive and the best regulated of the kind in Britain, and their eminence has been entirely brought forward by the exertions of a single person: John Marshall who has entirely raised himself from a humble individual to possess an income of not less than a hundred thousand pounds per annum.

(3) Thomas Carlyle, Reminiscences (1881)

By skillful, faithful and altogether human conduct in his (John Marshall) flax and linen manufactory at Leeds had made a large fortune and as a man worth having known, evidently a great deal of human worth and wisdom lying funded in him.

(4) William Brown, Flax Spinning in Leeds (1821)

The hands had very particular printed instructions set before them which are as particularly attended to. So strict are the instructions that if an overseer of a room be found talking to any person in the mill during working hours he is dismissed immediately. Everyone, manager, overseers, mechanics, oilers, spreaders, spinners and reelers, have their particular duty pointed out to them, and if they transgress, they are instantly turned off as unfit for their situation.

(5) John Marshall, Autobiography (unpublished)

My chief motive for having a seat in the House of Commons is a wish to see the mechanism by which the affairs of the men who take the lead in public life, and the principles on which they act. I also desired it as being creditable to my family and an introduction to good society.

(6) Dorothy Wordsworth wrote to Jane Marshall when she heard her husband was to retire from the House of Commons (1830)

Another parliament would have been too much to look forward to. He is wise to withdraw from this very arduous office which he has so honourably and usefully held. I fancy Mr. Marshall the gladdest of the glad on returning to his beautiful home among the mountains, free to stay in the quiet retirement that you all love so much.