Michael Davies

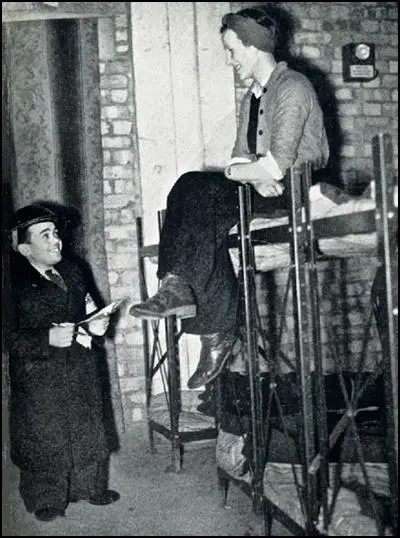

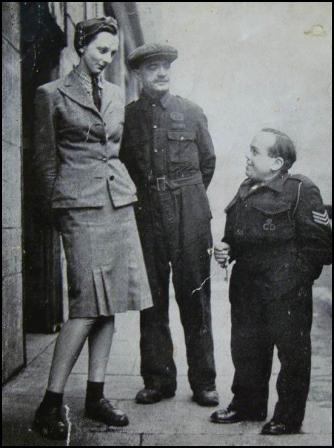

Michael (Mickey) Victor Davies (sometimes wrongly spelt Davis) was born in Stepney on 22nd April, 1910. As a result of a spine defect from birth he was, according to his daughter, only 4 feet 6 inches tall and became known as "Mickey Midget". He became an optician and became a well-known figure in the East End. (1)

Michael married Doris and lived in a large flat on the first floor of 103 Commercial Street, part of the London Fruit & Wool Exchange opposite Christ Church in Spitalfields. "The kitchen overlooked the indoor wholesale trading area and there was always a faint smell of fruit and veg in the background, while the front room overlooked Commercial St, roughly level with the overhead wires of the 647 and 665 trolley buses." (2)

On Saturday 7th September, 1940, at 4 p.m. 300 German bombers and 600 escorting fighters arrived over London. The Luftwaffe was heading for the Royal Victoria Docks and the Surrey Docks that were situated on the U-shaped bend of the Thames round the Isle of Dogs, and was unmistakable from the air. (3) Four hours later, 250 German bombers arrived and using the fires below as a marker, dropped 330 tons of high-explosives and 440 incendiary canisters. The docks were the principal target, but many bombs fell on the residential areas around them resulting in 448 Londoners being killed and another 1,600 were seriously injured during the air-raids that day. (4)

Between September 1940 and May 1941, the Luftwaffe made 127 large-scale night raids. Of these, 71 were targeted on London. On 13th September, 1940, Mickey's business was destroyed by a bomb. The government and the local councils had not provided enough deep public shelters. Stepney Borough Council decided to use the Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange in Brushfield Street. Built in 1929, as well as having a grand wood-panelled auction room seating 900, it had a maze of basement tunnels that could be used as an underground shelter. (5)

During the Blitz, Mickey and Doris, went to this shelter. Although designed for 2,500 people, over 5,000 crammed into the shelter. "The heat of the cellar", Davies wrote, "became literally hardly bearable. A steady stream of semi-conscious or unconscious people was passed towards the doorway." It was a chaotic situation and Davies inspired his fellow shelterers to create their own order. A shelter committee was democratically elected and Davies became chief shelter marshal. (6)

As Steve Hunnisett has pointed out: "To begin with, conditions were appalling, with almost non-existent sanitation, no proper bedding (people initially slept upon bags of rubbish) and minimal lighting. The floors soon became awash with urine, faeces and other filth. Mickey Davies was appalled by what he found and by the apparent lack of interest, or at best, will from the authorities to get things better organised. Davies was highly intelligent and more importantly, a superb organiser and he quickly became invaluable to the shelterers and a thorn in the side of the local authority in his efforts to improve the conditions for those using the shelter." (7)

The Daily Mirror reported: "In charge of one of London's biggest shelters is a dwarf - a little man who has performed wonders during the air raids and whose judgement is never questioned by any of the 2,000 shelterers whose safety is under his supervision." (8) Joseph Westwood, Under-Secretary of State for Scotland, was very impressed when he Mickey and told an audience in Edinburgh: "I wish you could have met Mickey. He is a dwarf. But in mind and spirit he is a giant. He is lord of one of the biggest shelters in London. Two thousand shelterers elected him chief shelter marshal." (9)

Ritchie Calder visited the shelter in September 1940 and wrote: "It was after midnight before I called in on my friend, Mickey the Midget. After hours of bombardment and barrage, of explosions and fires, I felt that even his shelter would be a refuge. But Mickey, three feet six inches of confident nonchalance, was on his way to the Crypt. He was tinhatless, as he dodged with me across the road.... We groped our way down into the murk of the Crypt.... We picked our way through huddles of old men and women, cramped on narrow benches or sprawled in the narrow aisles. It was bitterly cold and with every bomb thud, the sandwich board, 'Sinners Repent or Ye Perish,' which had been used to block a window, flapped, a grim reminder that the half-submerged window was blacked-out, not blocked-up." (10)

J. B. Priestley wrote about people like Mickey Davies who emerged as leaders during the Second World War: "It so happens that this war, whether those at present in authority like it or not, has to be fought as a citizen's war... They are a new type, what might be called the organized militant citizen. And the whole circumstances of their war-time favour of a sharply democratic outlook. Men and women with a gift for leadership now turn up in unexpected places. The new ordeals blast away the old shams. Britain, which in the years immediately before this war was rapidly losing such democratic virtues as it possessed, is now being bombed and burned into democracy." (11)

There is evidence that members of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) were involved in organising people in air-raid shelters. Euan Wallace, a Conservative Party cabinet minister, wrote: "There is little doubt that the Daily Worker and the Communist Party are taking the opportunity of creating trouble." (12) Ritchie Calder argued that "Mickey's form of common sense community socialism" was seen by some as "Communism". When told that there were "Communists" amongst the Shelter Committee, he replied that "There may be bigamists amongst them for all I care!" (13)

The poor sanitation in Mickey's Shelter increased the risk of disease and infection. "Mickey set up first aid and medical units, and raise money to equip a dispensary. He even persuaded stretcher bearers and others to come in on their off duty times to minister to the sick and injured." (14) Davis also persuaded Marks and Spencers to install a canteen. When the leading American politician, Wendell Willkie, visited London during the Blitz, he was taken to "Mickey's Shelter as a showplace of British democracy." (15) His daughter has pointed out that his shelter was "visited by people from American ex-Presidents to Clementine Churchill (all signed his visitors' book)." (16)

Ritchie Calder returned to the shelter near the end of the Blitz and reported: "Mickey the Midget took me back in 1941. The candles had given place to electric light. The tomb-card-table had given place to a buffet. Filthy bedclothes to tidy bunks. And, solemn monument to London's sanity, porcelain water closets had swept away the sarcophagi." (17)

Michael Davies, a member of the Labour Party, and a friend of Clement Attlee, was elected to Stepney Borough Council in 1949 and rose to be Deputy Mayor before he died in April 1954, during surgery for colon cancer. (18)

Primary Sources

(1) Ritchie Calder, Lilliput Magazine (1941)

It was what the Cockney with his gift for understatement called "a noisy night" last September. I was practising the gutter-flop in the back streets of Dockland. The clatter of the shrapnel was even more unnerving than the scream of the bombs. Incident had piled upon incident. Havoc had been let loose in East London. It was after midnight before I called in on my friend, Mickey the Midget. After hours of bombardment and barrage, of explosions and fires, I felt that even his shelter would be a refuge.

But Mickey, three feet six inches of confident nonchalance, was on his way to the Crypt. He was tinhatless, as he dodged with me across the road. We groped our way through the churchyard and pushed aside the damp, clammy draperies of the gas curtain, to be challenged by a sentinel shadow, who added to the impression that this was a kind of secret society. Mickey passed me through. We groped our way down into the murk of the Crypt. In these vaults were massive stone sarcophagi. The heavy stone lids of these coffins had been levered off. The bones and dust of the centuries had been tipped out. The last resting-place of the dead had been claimed by the living and in one of them, as though he were lying in state, was a navvy, snoring blissfully and stirring up the bone dust with every snore. In a recess, by the light of trembling candle-flames, a macabre card school was playing solo. Their card-table was a tomb. The new death was so near that the old death had no reality.

We picked our way through huddles of old men and women, cramped on narrow benches or sprawled in the narrow aisles. It was bitterly cold and with every bomb thud, the sandwich board, "Sinners Repent or Ye Perish," which had been used to block a window, flapped, a grim reminder that the half-submerged window was blacked-out, not blocked-up.

Mickey the Midget scrambled ahead of me up a hen-ladder to the family pews recessed in the wall and as I peered over the ledge, I was confronted by a brown baby face with startled black eyes under a turban. The black eyes goggled in the flickering candle light and then the baby disappeared under the bedclothes beside its Indian mother. Stretched majestically on the rough floor was the long figure of an ex-Bengal lancer with his shovel beard over the blanket, his head turbanned. A cockney family was asleep in a niche above.

The squalor of this crypt, like most of the shelters last September, was indescribable. It seemed then as though humanity had descended into a pit of degradation, out of which it could never struggle...

Mickey the Midget took me back in 1941. The candles had given place to electric light. The tomb-card-table had given place to a buffet. Filthy bedclothes to tidy bunks. And, solemn monument to London's sanity, porcelain water closets had swept away the sarcophagi.

(2) Mike Brooke, The Docklands and East London Advertiser (5th February 2013)

A ‘people’s hero’ of the wartime Blitz who ran one of London’s biggest public air-raid shelters in the reinforced basement of the Exchange is being featured in the ‘Optician’ trade journal.

Optometrist David Baker has researched the story of Mickey Davis, a 3ft 3ins midget who ran the shelter for up to 5,000 people a night, one of the few safe havens for the East End’s working class during the nightly Luftwaffe air-raids in 1940.

Mickey Davis himself was an optician who was bombed out of his East End premises in the air-raids and spent his time instead organising the shelter. His fame spread and even American war correspondents wrote about “the midget with a giant heart.”

Mickey persuaded companies like Marks & Spencer to donate food to run a shelter canteen, the profits of which were used for free milk for children - the fore-runner of the post-War welfare state...

Mickey went on to be elected a Stepney borough councillor in 1949 and rose to be Deputy Mayor before he died in 1956 at 49, during an operation to correct a spine defect from birth.

(3) Mickey the Midget (2nd March, 2012)

The London Fruit & Wool Exchange was built in 1929 to handle the post-WWI boom in produce coming through the East End docks. Designed by architect Sydney Perks (whose other creations include Snow Hill Police Station near St Bart’s in the City of London) it features a lovely sweeping staircase, lots of parquet and brass, grand wood-panelled auction rooms seating 900, glass ceilings created to simulate daylight even on London’s foggiest days, and a maze of basement tunnels that sheltered locals during the Blitz.

In fact, the Exchange was once regarded as London’s most inhospitable air raid shelter but conditions were dramatically improved following the campaigning actions of famed local resident, 3ft tall hunchback optician Mickey Davies, aka ‘Mickey the Midget’. Soon, there were toilets, beds, cleaning rotas and even musical entertainment. The site went down in East End legend as Mickey’s Shelter.

(4) Mike Brooke, Mickey Davis at the Fruit & Wool Exchange (6th March, 2012)

The last time I saw Mickey Davis I was as tall as him – and I was only seven or eight, back then in the Spitalfields of the early nineteen fifties. He came to my school, Robert Montefiore Primary in Deal St, as guest of honour for our annual prize giving. I recognised him in the corridor as we left the assembly hall afterwards, standing against the wall watching us return to our classrooms. I was the proudest kid on the block – because the guest of honour was my Uncle Mickey.

He was, I recall, Deputy Mayor of Stepney (the old Metropolitan borough that later became absorbed into what we now call Tower Hamlets), a very short man, a midget through an accident at birth or defect, I'm not sure exactly. But Mickey was a giant of a man to the community he served in those post-war years and a "people's hero" of the London Blitz of 1940, several years before I was even born, as I discovered as a journalist working in the East End more than half-a-century later.

I must have been about eight when I roller-skated through the streets of Spitalfields one afternoon and found myself in Fournier St and decided to pop in to see aunt Doris and husband Mickey who lived in a large flat on the first floor of 103 Commercial St, part of the London Fruit & Wool Exchange opposite Spitalfields Church (now known as Christ Church). The kitchen overlooked the indoor wholesale trading area and there was always a faint smell of fruit and veg in the background, while the front room overlooked Commercial St, roughly level with the overhead wires of the 647 and 665 trolleybuses. It seemed quite a posh apartment to an eight-year-old.

But I didn't go inside that afternoon. My grandmother, aunt Doris and my late father Henry's mother, answered the door and told me immediately that uncle Mickey was dead. It was an abrupt manner to an eight-year-old, but I knew she was upset. I left and skated straight home to Granby St, along Brick Lane, rushing to tell my mother. She had not heard about Mickey yet, but knew he had been in hospital. We did not have a phone in the house in those days.

Doris and my mother Connie had been great friends during the War and worked together. It was through Doris that my mother and father met when he came home on leave from the Royal Navy in 1943. He visited his sister at work and took a fancy to Connie. They married while he was on leave and he was recalled back to Plymouth to rejoin his ship on their wedding night, so my mother once told me.

My mother immediately put a coat on and went over to see Doris that day in 1954 when I told her about the death of Uncle Mickey. It was not until decades later that I learned the full story of Mickey Davis – and how he organised a shelter committee during the early days of the Blitz at the Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange – when the BBC contacted my family in the nineteen eighties, researching a possible documentary, though I do not think the programme was ever made. It was another two decades before I did my own research for an article about Mickey Davis for a commemorative supplement in the East London Advertiser, where I was Features Editor, marking the seventieth anniversary of the start of the Blitz in September 2010,.

Mickey, who at three feet three inches tall was known as ‘"the Midget," was an East End optician who threw his energies into organising and improving shelter life, I wrote. He had emerged as the unofficial leader who pushed for improvements to health and safety in one of the East End's biggest air raid shelters at the Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange in Brushfield St. While the local authority, Stepney Borough Council, was concerned by the 2,500 people crammed into the shelter each night, with its lack of sanitation, risking disease and infection, and lack of facilities for food, lighting and heating, it was left to Mickey set up first aid and medical units, and raise money to equip a dispensary. He even persuaded stretcher bearers and others to come in on their off duty times to minister to the sick and injured. As a popular activist and orator, he became indispensable to the people, pushing the authorities into action.

Long before medical posts became the official practice, well-to-do friends of Mickey provided his Spitalfields public shelter with drugs and equipment. A GP friend made two-hour journeys each day to the East End to spend his nights among the poor. Eight years before the NHS was set up, Mickey's shelter in 1940 had a free medical service already up-and-running. He even devised a card index system of everyone who used the shelter, and introduced hygiene practices and protection against disease. He persuaded Marks & Spencer to donate money for a canteen and used the profits to provide free milk for children. When the wartime Government eventually appointed official shelter marshals, Mickey was replaced – but the first action of the Spitalfields Shelter Committee undertook was to vote him to be Shelter Marshal, responsible for 2,500 people.

His thinking in 1940 was a fore-runner of the post-war Welfare State that emerged in 1948. He was a man known affectionately among East Enders as "the midget with the heart of a giant." That was the Mickey Davis, who I am proud to have called "uncle."

(5) Steve Hunnisett, Lilliput, The Blitz and Mickey the Midget (21st March, 2016)

Mickey Davies, for that was his real name, was a 29 year old optician, whose shop was reputedly located somewhere close to Spitalfields, in what we now know as the Borough of Tower Hamlets but which in 1940, formed part of the Metropolitan Borough of Stepney. Strangely perhaps, there are no records in local trade directories as to where this business was actually located but according to Mickey himself, it was destroyed by a German bomb on 13th September 1940. Mickey was only 4 feet 6 inches tall and with a mis-shapen back, hence his somewhat politically incorrect nickname but the destruction of his shop enabled him to devote time to helping those in the Spitalfields Shelter. In addition to his optician business, Mickey was also a local social activist and indeed was later to become a Stepney borough councillor and briefly, Deputy Mayor before his death in the 1950s. His activism was very much geared towards helping people in his local community and in wartime, ensuring that their shelter facilities were safe, sanitary and the equal of anything for those provided to the wealthier citizens of London in the West End.

The shelter in question was located beneath the London Fruit and Wool Exchange in Brushfield Street, now sadly demolished and comprised a cavernous basement, which was capable of holding some 2,500 people in relative safety, although in practice, over twice that number frequently crammed into the space.

To begin with, conditions were appalling, with almost non-existent sanitation, no proper bedding (people initially slept upon bags of rubbish) and minimal lighting. The floors soon became awash with urine, faeces and other filth. Mickey Davies was appalled by what he found and by the apparent lack of interest, or at best, will from the authorities to get things better organised. Davies was highly intelligent and more importantly, a superb organiser and he quickly became invaluable to the shelterers and a thorn in the side of the local authority in his efforts to improve the conditions for those using the shelter.

Firstly, he set about improving the sanitary conditions in the shelter as well as providing education about hygiene and establishing disease prevention practices in the shelter. He then began to get shelter users themselves to provide First Aid and Medical supplies by organising collections to purchase what was needed. Trained in First Aid himself, he then persuaded local Stretcher Parties to give up their off duty time to tend to the sick and injured in the shelter. He also built up a card index system recording the medical history of each person using the shelter and created what he called a "Passport to Health" amongst the shelterers. Using his many contacts in the profession, he also procured the services of a GP to visit the shelter every night. Proper steel bunk beds were also installed, which ensured that shelterers could get a decent night's sleep.

Student Activities

References

(1) Mike Brooke, The Docklands and East London Advertiser (5th February 2013)

(2) Mike Brooke, Mickey Davis at the Fruit & Wool Exchange (6th March, 2012)

(3) Angus Calder, The People's War (1969) page 163

(4) Peter Stansky, The First Day of the Blitz (2007) page 121

(5) Mickey the Midget (2nd March, 2012)

(6) Angus Calder, The People's War (1969) page 183

(7) Steve Hunnisett, Lilliput, The Blitz and Mickey the Midget (21st March, 2016)

(8) The Daily Mirror (8th February, 1941)

(9) Aberdeen Press and Journal (8th February, 1941)

(10) Ritchie Calder, Lilliput Magazine (1941)

(11) J. B. Priestley, Out of the People (1941)

(12) Philip Ziegler, London at War: 1939-1945 (1995) page 168

(13) Steve Hunnisett, Lilliput, The Blitz and Mickey the Midget (21st March, 2016)

(14) Mike Brooke, Mickey Davis at the Fruit & Wool Exchange (6th March, 2012)

(15) Ritchie Calder, Carry on London (1941) page 42

(16) Steve Hunnisett, Lilliput, The Blitz and Mickey the Midget (21st March, 2016)

(17) Ritchie Calder, Lilliput Magazine (1941)

(18) Simone Davies, email to John Simkin (25th June, 2019)