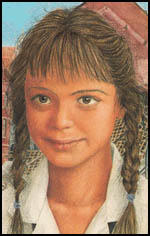

Ilse Koehn

Ilse Koehn was born in Berlin in August 1929. Her parents were active members of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and were very opposed to the policies of the Nazi Party. Her mother was a strong supporter of women's rights.

Ernst Koehn had a good job as an electrician for the Berlin Light and Power Company. His mother, Oma Koehn, was Jewish.

This created problems for the family when Adolf Hitler achieved power in 1933. By October 1933, "non-Aryans" were legally excluded from institutions of higher learning, from the government, and from the professions.

Hitler ordered that books whose authors were either Jewish or in opposition to fascism should be burned. This frightened Ernst and Grete Koehn: "My parents crammed most of their now forbidden books into two huge crates and buried them at night in our garden." (1)

Ilse Koehn and the Nuremberg Laws

On 15th September, 1935, announced what became known as the Nuremberg Laws. Under the first law, Jews forfeited German citizenship. The second law prohibited marriage and sexual intercourse between "Aryans" and Jews. On 14th November, 1935, the government declared that persons with three or four Jewish grandparents were full Jews; those with two "Aryan" and two Jewish grandparents were "half-Jews". (2)

Under these laws, Ilse Koehn, with one Jewish grandparent, was a "Mischling, second degree". As she later pointed out: "The law stated as irrefutable fact that a grandparent was Jewish if he/she was racially Jewish, even if that grandparent was not of the Jewish faith and did not belong to the Jewish religious community." (3)

Education in Nazi Germany

It has been estimated that by 1936 over 32 per cent of teachers were members of the Nazi Party. This was a much higher figure than for other professions. Teachers who were members, wore their uniforms in the classroom. The teacher would enter the classroom and welcome the group with a ‘Hitler salute’, shouting "Heil Hitler!" Students would have to respond in the same manner. It has been claimed that before Adolf Hitler took power a large proportion pf teachers were members of the German Social Democratic Party. One of the jokes that circulated in Germany during this period referred to this fact: "What is the shortest measurable unit of time? The time it takes a grade-school teacher to change his political allegiance." (4)

By the time Ilse Koehn went to school in 1939 she found that the young teachers were strong supporters of Adolf Hitler. "Dr. Lauenstein was the only male teacher. Young and tall, handsome too, he was quite a contrast to the ladies, who were all in their fifties. He alone wore the Nazi Party button, shouted "Heil Hitler" when he entered the classroom and spent the next fifteen minutes expounding on the Fuhrer's "Blood and Soil" philosophy. Old German soil soaked with German blood, as he put it. He was unbearably bombastic when he talked about the superior Aryan race. When he finally turned to Goethe, there was always a sigh of relief. No one, certainly not I, had any idea what he had been talking about. But when he dedicated himself to "the great Goethe" he held us spellbound, made us see and feel the beauty of Goethe's language. He seemed wonderful then." (5)

Second World War

On 23rd August, 1939, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin signed the Nazi-Soviet Pact. A week later, on 1st September, the two countries invaded Poland. Within 48 hours the Polish Air Force was destroyed, most of its 500 first-line planes having been blown up by German bombing on their home airfields before they could take off. Most of the ground crews were killed or wounded. In the first week of fighting the Polish Army had been destroyed. On 6th September the Polish government fled from Warsaw. (6)

Ilse Koehn's parents reacted differently to those of her friends: "In September 1939 Hitler invaded Poland. Britain and France declared war on Germany. We were at war.... My family said that Hitler was leading Germany to doom and destruction. Hitler said he was leading us to glory, and my classmates seemed to believe him. They eagerly listened to the radio broadcasts that in my home were shut off. Why did we have to be so different?" (7)

At the age of ten Ilse wanted to join the German Girls' League. Her friends "Inge and Waltraud... had told me how much fun they had, singing and playing all kinds of games. When I mentioned it to father, he had looked at me as if I were a ghost, then yelled, Join an organization of those pigs? Then father calmed himself and he sat down beside me. " He then explained: "Listen, it may be true that all they do is sing and play games. But their very songs and games are designed to teach you the Nazi philosophy. And you know that we do not believe in it. Young people are impressionable and the Nazis use their enthusiasm for their own ends. There are things that you are too young to understand. When the time comes, you and I will have a long talk." (8)

As a result of heavy bombing of Berlin, Ilse Koehn and her classmates were evacuated to East Prussia. She was one of a batch of 1,000 children sent to this safe area. The station was decorated with garlands and banners and they were greeted by Hitler Youth and Nazi Party dignitaries. This included Baldur von Schirach, the Reich Youth leader. However, the authorities had lied to their parents and they were in fact sent to the recently occupied Czechoslovakia. (9)

The camp was under the control of the Hitler Youth. Discipline was very strict. They had to fold their flannel nightgowns into regulation squares. "they actually check whether all folded garments are the same height and width - with a ruler!" Every morning their uniform was inspected. Then they would be marched in formation around the area. After being fired at as they passed a few trees, they had to restrict their activities to the village square. (10)

In September 1941, the authorities decided the area was unsafe and the children returned to Berlin. The people were responsible for building their own air raid shelters. "Everyone is required to have one, and anyone without a cellar has to build a shelter as protection against bomb and grenade fragments. Our cellar is officially fit for twenty-five people." (11)

Her father told her stories about the behaviour of the German armed forces: "We Germans have done terrible things in Poland and Czechoslovakia. He tells me about the small Czech village of Lidice, where the Führer's Aryan supermen, the proud troops, put every man, woman and child against a wall and shot them in cold blood while they burned down the houses." When his wife tried to stop him telling these stories he retorted: "I want Ilse to know why all Germans, anything German, will soon be something hateful and despicable to the rest of the world. Thanks to big Adolf and his henchmen." (12)

The family used to listen to BBC reports of the war and they grew to love the broadcasts of Lindley Fraser. "First there are squeaks and beeps, then boom-boom-boom, pause, then the same drum sequence again, the last boom a particularly low, long-lasting one. Then a voice: London calling! London calling! This is Lindley Fraser for the BBC. It is exciting. I hold my breath. Vati whispers unnecessarily, Hear that? as the announcer continues in German. Low! Turn it low, lower, Ernst! Oma sounds alarmed. She hands Vati her blanket. Here, better take this!"

Ilse Koehn later recalled in her autobiography: "The blanket covers us and the radio like a tent as we listen to a broadcast unlike any I have ever heard. This man, in faraway London, talks about German troops retreating from Moscow, Leningrad, of General Rommel being beaten in North Africa. He names specific army units, commanders, places that our 'victorious armies' have abandoned. I wonder how he knows, and suddenly I remember the posters that are all over Berlin. They show a black-cloaked, mean-faced man under the headline: Psst! The enemy listens! I understand better t now what I hear constantly on the German radio stations: Those who listen to foreign broadcasts and talk about our troop movements, are the enemy within. In my mind I hear the hysterical voice of Propaganda Minister Goebbels: These despicable creatures are knifing the German people in the back. They must be erased from the face of the earth. Death by hanging is too good for them. And now I'm more scared than.Oma and wish Vati would turn the set lower still, but I am also fascinated and want to hear more." (13)

In February 1943, Ilse Koehn heard about the arrest of members of the resistance called the White Rose group. "The radio announcer calls them abominable, a cancer on the body of the German people that must be eliminated, burned out." (14) Hans Scholl, Sophie Scholl, Kurt Huber, Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf and Christoph Probst were executed later that month. (15)

The following month the authorities began arresting Jews in Berlin. According to Joseph Goebbels: "We are now definitely pushing the Jews out of Berlin. They were suddenly rounded up last Saturday, and are to be carted off to the East as quickly as possible. Unfortunately our better circles, especially the intellectuals, once again have failed to understand our policy about the Jews and in some cases have even taken their part. As a result our plans were tipped off prematurely, so that a lot of Jews slipped through our hands. But we will catch them yet." (16)

On 21st July, 1944, Ilse Koehn heard about the attempt on the life of Adolf Hitler by Claus von Stauffenberg and his group (July Plot): "The Führer himself goes on the radio, assuring the German people that he is alive and well, that he has not sustained more than a few cuts and bruises. Providence has intervened in his behalf, he says. The revolt, hatched by German generals, has been completely suppressed. All the conspirators have been killed or have committed suicide." (17)

In November 1944, Ilse Koehn received news about the D-Day landings: "The Allies are on German soil. Some say they are fifty kilometers away, others claim that they are already in Prague. We are about eighty kilometers north-east of Prague... Whatever you believe, one thing is certain: The front is coming close. We can hear it. When the wind is just right, we can hear the distant rumble of heavy artillery. At first we thought it was a thunderstorm." (18)

The bombing raids over Berlin became more intense. On 3rd February, 1945, one thousand bombers attacked the city: "Oh my God! What a sight! Hundreds, thousands of airplanes are coming toward us! The whole sky is a glitter with planes. Planes flying undisturbed in perfect V formation, their metal bodies sparkling in the sun. And no anti-aircraft guns. Only the terrifying, quickly intensifying hum of engines, thousands of engines. The air vibrates, seems to shiver; the water, the ground and the bridge under us begin to tremble. It's unearthly, a tremendously beautiful sight! A whole blue sky full of silver planes. We run. The first formation is already overhead. All hell breaks loose. The anti-aircraft guns shoot and bombs fall like rain. Millions of long, rounded shapes come tumbling down around us. The sky turns gray, black, the earth erupts. The detonations begin to sound like continuous thunder." (19)

In the final months of the war members of the Hitler Youth, some aged only 14 and 15, fought on the front-line against the advancing Allies. (20) On 3rd March, 1945, Ilse Koehn's teacher, Dr. Graefe, announced: "Today your Fatherland has called the class of 1929... Those born in 1929 are called up to bear arms. Those whose names I will read will report for duty as flak helpers in the assembly hall tomorrow morning at nine: Breller, Choenbach, Gerhard, Mertens, Mons, Mueller, Schubach and Tetzlaff." Koehn commented that "his voice is toneless" and as he leaves the room he mumbles "insanity". However, she points out that the boys whose names had been called out, who are only 16-years-old, "are clearly overjoyed... they feel like men." (21)

Harrison E. Salisbury has pointed out that Ilse Koehn and her parents were lucky to survive the war: "Both her parents survived the war. Her father, who was the most vulnerable, managed to survive because, essentially, he was too valuable an electrical engineer to be spared. They were all fortunate in escaping, sometimes by seconds and often by only a few rods, the terrifying British and American bombing raids." (22)

After marrying John Van Zwienen the couple moved to New York City. Over the next few years they worked as writers, illustrators and graphic designers. In 1977 Ilse Koehn published her autobiography, Mischling, Second Degree: My Childhood in Nazi Germany. It received many awards including the Jane Addams Peace Foundation Award for nonfiction. (23)

Ilse Koehn, died of a heart attack, aged 61, on 8th May, 1991, at her home in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Primary Sources

(1) Ilse Koehn, Mischling, Second Degree: My Childhood in Nazi Germany (1977)

Dr. Lauenstein was the only male teacher. Young and tall, handsome too, he was quite a contrast to the ladies, who were all in their fifties. He alone wore the Nazi Party button, shouted "Heil Hitler" when he entered the classroom and spent the next fifteen minutes expounding on the Fuhrer's "Blood and Soil" philosophy. Old German soil soaked with German blood, as he put it. He was unbearably bombastic when he talked about the superior Aryan race. When he finally turned to Goethe, there was always a sigh of relief. No one, certainly not I, had any idea what he had been talking about. But when he dedicated himself to "the great Goethe" he held us spellbound, made us see and feel the beauty of Goethe's language. He seemed wonderful then.

In September 1939 Hitler invaded Poland. Britain and France declared war on Germany. We were at war.... My family said that Hitler was leading Germany to doom and destruction. Hitler said he was leading us to glory, and my classmates seemed to believe him. They eagerly listened to the radio broadcasts that in my home were shut off. Why did we have to be so different?

(2) Ilse Koehn, Mischling, Second Degree: My Childhood in Nazi Germany (1977)

While still in Hermsdorf I had wanted to join the Jungmaedel, as the ten-to-fourteen-year-old girls of the Hitler Youth were called, because of Inge and Waltraud. They had told me how much fun they had, singing and playing all kinds of games. When I mentioned it to father, he had looked at me as if I were a ghost, then yelled, "Join an organization of those pigs?" Then father calmed himself and he sat down beside me. "Listen," he said, "it may be true that all they do is sing and play games. But their very songs and games are designed to teach you the Nazi philosophy. And you know that we do not believe in it. Young people are impressionable and the Nazis use their enthusiasm for their own ends. There are things that you are too young to understand. When the time comes, you and I will have a long talk."

(3) Ilse Koehn, Mischling, Second Degree: My Childhood in Nazi Germany (1977)

First there are squeaks and beeps, then boom-boom-boom, pause, then the same drum sequence again, the last boom a particularly low, long-lasting one. Then a voice: "London calling! London calling! This is Lindley Fraser for the BBC." It is exciting. I hold my breath. Vati whispers unnecessarily, "Hear that?" as the announcer continues in German."Low! Turn it low, lower, Ernst!" Oma sounds alarmed. She hands Vati her blanket. "Here, better take this!"

The blanket covers us and the radio like a tent as we listen to a broadcast unlike any I have ever heard. This man, in faraway London, talks about German troops retreating from Moscow, Leningrad, of General Rommel being beaten in North Africa. He names specific army units, commanders, places that our "victorious armies" have abandoned. I wonder how he knows, and suddenly I remember the posters that are all over Berlin. They show a black-cloaked, mean-faced man under the headline: "Psst! The enemy listens!" I understand better t now what I hear constantly on the German radio stations: "Those who listen to foreign broadcasts and talk about our troop movements, are the enemy within." In my mind I hear the hysterical voice of Propaganda Minister Goebbels: "These despicable creatures are knifing the German people in the back. They must be erased from the face of the earth. Death by hanging is too good for them." And now I'm more scared than.Oma and wish Vati would turn the set lower still, but I am also fascinated and want to hear more.

"The tide is turning. Finally, my girl, the tide is turning," Vati, says. To my great relief, he switches to a station with music. "Be on your guard, observant, alert. You know I would like to protect you, look after you, but I can't. You'll have to do it yourself."

(4) Ilse Koehn, Mischling, Second Degree: My Childhood in Nazi Germany (1977)

The Allies are on German soil. Some say they are fifty kilometers away, others claim that they are already in Prague. We are about eighty kilometers north-east of Prague... Whatever you believe, one thing is certain: The front is coming close. We can hear it. When the wind is just right, we can hear the distant rumble of heavy artillery. At first we thought it was a thunderstorm.

(5) Ilse Koehn, Mischling, Second Degree: My Childhood in Nazi Germany (1977)

Oh my God! What a sight! Hundreds, thousands of airplanes are coming toward us! The whole sky is aglitter with planes. Planes flying undisturbed in perfect V formation, their metal bodies sparkling in the sun. And no anti-aircraft guns. Only the terrifying, quickly intensifying hum of engines, thousands of engines. The air vibrates, seems to shiver; the water, the ground and the bridge under us begin to tremble. It's unearthly, a tremendously beautiful sight! A whole blue sky full of silver planes.

We run. The first formation is already overhead. All hell breaks loose. The anti-aircraft guns shoot and bombs fall like rain. Millions of long, rounded shapes come tumbling down around us. The sky turns gray, black, the earth erupts. The detonations begin to sound like continuous thunder.

A house! Shelter from this nightmare. We reach it, though I don't know how. I collide with the old lady who is standing in the door. She tries to take the baby away from me. We stand in the doorway, entangled by the pail, and I see the bomb, watch it hit the roof, and see the house cave in behind her.

"God in Heaven!" she screams. "God in Heaven!"

"Grandma! Grandma!" wails the little girl, pulling at her skirt. "Grandma, let's go to the bunker, please, please, Grandma!"

I'm flat on the ground. Bombs, bombs, bombs fall all around me. It can't be. It's a dream. There aren't that many bombs in the whole world. Maybe I'm dead? I get up, drag pail, old woman and girl with me toward a porch, a concrete porch with space underneath. Above the detonations, flak fire, shattering glass rises the old woman's high-pitched voice: "God in Heaven! God in Heaven!" And now the baby is wailing too.

Hang on to the earth. It heaves as if we are on a trampoline, but I cling to it, dig my nails into it.

(5) New York Times (16th May, 1991)

Ilse Koehn, a writer and graphic artist, died on May 8 at her home in Greenwich, Conn. She was 61 years old.

Ms. Koehn died of a heart attack, a spokesman for the family said.

She moved to New York City from West Berlin in 1958 and worked as an art director for the J. Walter Thompson and Campbell-Downe advertising agencies. After she moved to Greenwich in 1970, she and her husband, John Van Zwienen, worked together as writers, illustrators and graphic designers. The couple later divorced.

Ms. Koehn's first book, Mischling, Second Degree, described her experiences as a child of part-Jewish parentage growing up in Berlin under the Nazis and in evacuation camps during World War II. The book was published in six countries outside the United States, including Britain, France and West Germany. It received the Boston Globe Hornbook Award, the Jane Addams Peace Foundation Award for nonfiction and the Lewis Carroll Shelf Award as a book recommended for young readers.

Ms. Koehn was a member of the Graphic Artists Guild and the Authors Guild.

She is survived by a stepdaughter, Kyle Van Zwienen of Webster, Mass.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)