Arthur Zimmermann

Arthur Zimmermann was born in Marggrabowa, East Prussia, on 5th October, 1864. He studied law from 1884-87. He worked as a lawyer before receiving his doctorate of law. In 1893, he took up a career in diplomacy and entered the consular service in Berlin. In 1896 he was sent to China and by 1900 he had risen to the rank of consul. In 1911 he was appointed Under Secretary of State in the German Foreign Office.

On 18th October 1913 the Austrian Government sent an ultimatum to Belgrade, demanding the evacuation of Albania by Serbian forces within eight days. Zimmermann told the British Ambassador in Berlin, Sir Edward Goschen: "He had been surprised that the Emperor of Austria endorsed a policy which, under certain circumstances, might lead to serious consequences, but he had done so, and that made it clearer still that restraining advice in Vienna on the part of Germany was out of the question." (1)

On 24 November 1916, Zimmermann replaced Gottlieb von Jagow as Secretary of State. Zimmermann became convinced that Germany should step up its unrestricted submarine warfare policy, including attacks on American shipping. This was a policy that had been halted on 20th April after President Woodrow Wilson had complained about the sinking of the SS Sussex with several American civilians onboard. (2)

Zimmermann Telegram

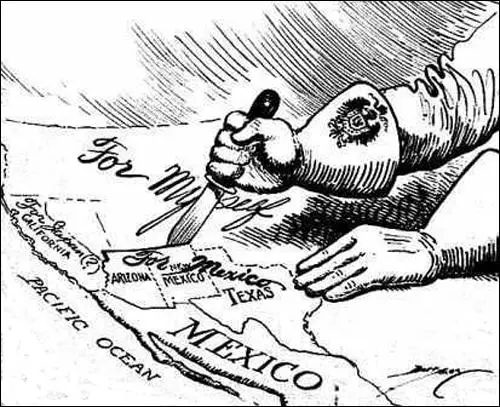

On 16th January 1917, Zimmermann, sent a coded telegram to the ambassador in Mexico City where he informed him that Germany intended to begin unrestricted submarine warfare on 1st February. He also instructed the ambassador to propose an alliance with Mexico if war broke out between Germany and the United States. In return, the telegram proposed that Germany and Japan would help Mexico regain the territories that it lost to the United States in 1848 (Texas, New Mexico and Arizona). (3)

On the outbreak of the First World War the Admiralty established the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS). People such as Alastair Denniston, Alfred Dilwyn Knox and Frank Birch were involved in intercepting, decrypting, and interpreting naval staff German and other enemy wireless and cable communications. GCCS obtained a copy of the Zimmermann Telegram and after it was decrypted it was passed to the American government. (4)

When he received details of the Zimmermann Telegram, President Woodrow Wilson did not immediately declare war and instead commented, "We are the sincere friends of the German people and earnestly desire to remain at peace with them. We shall not believe they are hostile to us unless or until we are obliged to believe it". (5)

Zimmermann made a speech where he admitted sending the telegram. However, he hoped that the USA would remain neutral. He pointed out that his instructions to the Mexican government were only to be carried out after America declared war, and blamed President Wilson for breaking off relations with Germany "with extraordinary roughness" after the telegram was received, and that therefore the German ambassador "no longer had the opportunity to explain the German attitude, and that the US government had declined to negotiate". (6)

Lenin and the Russian Revolution

On 10th March, 1917, Tsar Nicholas II had decreed the dissolution of the Duma. The High Command of the Russian Army now feared a violent revolution and on 12th March suggested that he should abdicate in favour of a more popular member of the royal family. Attempts were now made to persuade Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich to accept the throne. He refused and the Tsar recorded in his diary that the situation in "Petrograd is such that now the Ministers of the Duma would be helpless to do anything against the struggles the Social Democratic Party and members of the Workers Committee. My abdication is necessary... The judgement is that in the name of saving Russia and supporting the Army at the front in calmness it is necessary to decide on this step. I agreed." (7)

Prince George Lvov, was appointed the new head of the Provisional Government. A few days later Lvov declared that all political prisoners living exile could return to their homes. On 19th March, 1917, several political exiles living in Zurich had a meeting about the best way to get back to Russia. Julius Martov suggested that they should offer the German government some sort of deal in order to obtain help in returning to their homeland. (8)

Lenin agreed and he asked Robert Grimm to send a message to Count Gisbert von Romberg, the German ambassador in Berne. This information was passed to Arthur Zimmermann who agreed to a deal. Alexander Parvus, a former revolutionary, but now a German arms-dealer, who had known Lenin since 1900, was brought in to handle negotiations. After a meeting with Chancellor Theobald Bethmann-Hollweg, it was decided that the plan to allow Lenin and other senior Bolsheviks to travel through Germany in order to get to Petrograd was a "brilliant manoeuvre". (9)

General Erich Ludendorff, the German Chief of Staff, was consulted about the plan and he welcomed the move. "Our government, in sending Lenin to Russia, took upon itself a tremendous responsibility. From a military point of view his journey was justified, for it was imperative that Russia should fall." (10)

Lenin, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Gregory Zinoviev, Inessa Armand, Karl Radek and five other Bolsheviks boarded their "sealed" train at Zurich Central Station. A small group of other revolutionaries heard about what was going on and shouted out: "Spies! German spies!" The train took them through Germany. "The train had been given a high traffic priority by the Germans - so high that the German Crown Prince was delayed for two hours to let it pass." The train eventually reached Sweden and from there they travelled to Petrograd. (11)

United States enters the First World War

On 21st March the United States tanker, The Healdton, was sunk by a German submarine while in a specially declared "safety zone" in Dutch waters. Twenty American crewmen were killed. Wilson called a meeting with his Cabinet and it unanimously decided to go to war. On 2nd April, President Wilson asked for permission to go to war. This was approved in the Senate on 4th April by 82 votes to 6, and two days later, in the House of Representatives, by 373 to 50. Still avoiding alliances, war was declared against the German government (rather than its subjects). (12)

Germany was confident that they could bring Britain to collapse before American action became effective. As A. J. P. Taylor pointed out: "They nearly succeeded. The number of ships sunk by U-boats rose catastrophically. In April 1917 one ship out of four leaving British ports never returned. That month nearly a million tons of shipping were sunk, two thirds of it British. New building could replace only one ton in ten. Neutral ships refused cargoes for British ports. The British reserve of wheat dwindled to six weeks' supply." (13)

When the USA declared war in April 1917, Wilson sent the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) under the command of General John Pershing to the Western Front. The Selective Service Act, drafted by Brigadier General Hugh Johnson, was quickly passed by Congress. The law authorized President Wilson to raise a volunteer infantry force of not more than four divisions. Pershing arrived in France in June 1917, with his troops and initially stated that they were at the disposal of General Ferdinand Foch. "It was an inspiring gesture - although in practice he continued to keep a tight hold on his troops and, with rare exceptions, only allowed them to take over parts of the front as complete divisions." (14)

The sending of the Zimmermann Telegram was a diplomatic disaster and on 6th August, 1917, Zimmermann resigned as foreign secretary and was succeeded by Richard von Kühlmann.

Arthur Zimmermann died of pneumonia on 6th June, 1940.

Primary Sources

(1) Arthur Zimmermann, telegram to Heinrich von Eckardt, the German ambassador to Mexico (19th January, 1917)

We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The settlement in detail is left to you. You will inform the President of the above most secretly as soon as the outbreak of war with the United States of America is certain and add the suggestion that he should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves. Please call the President's attention to the fact that the ruthless employment of our submarines now offers the prospect of compelling England in a few months to make peace.

Student Activities

Sinking of the Lusitania (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)