On this day on 25th July

On this day in 1806 anti-slavery campaigner Maria Weston was born in Weymouth, Massachusetts. When she was twenty-four she married Henry Grafton Chapman, a Boston merchant. Both became campaigners against slavery and in 1832 Maria joined with twelve other women to form the Boston Anti-Slavery Society.

Chapman worked closely with William Lloyd Garrison and helped him edit The Liberator. In 1836 she compiled Songs of the Free and Hymns of Christian Freedom. Three year later she published Right and Wrong in Massachusetts, a pamphlet that discussed the divisions in the Anti-Slavery Society that was being created over the issue of woman's rights.

In 1839 Chapman and two other women, Lucretia Mott and Lydia Maria Child were elected to the executive committee of the Anti-Slavery Society. This upset some members of the society who were extremely upset by this decision. Lewis Tappan, the brother of Arthur Tappan, the president of the society, argued that: "To put a woman on the committee with men is contrary to the usages of civilized society."

Whereas one leaders, such as William Lloyd Garrison, Theodore Weld, Wendell Phillips and Frederick Douglass were as committed to women's rights as they were to the abolition of slavery. Others disagreed with this view and in 1840 a group including Arthur Tappan, James Birney and Gerrit Smith left the Anti-Slavery Society and formed a rival organization, the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society.

Chapman was editor of the anti-slavery journal, Non-Resistance in New England (1839-1842). Other books written by Chapman included Memorials of Harriet Martineau (1877). Her grandson, John Jay Chapman, was also a campaigner for social reform and an outstanding literary critic.

Maria Weston Chapman died on 12th July, 1885.

On this day in 1834 poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge died of a heart attack in 1834..

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the youngest son of the vicar of Ottery St Mary, Devon, was born in 1772. He was educated at Christ's Hospital and Jesus College, Cambridge with the intention of becoming a Church minister.

At university Coleridge became interested in politics and was a strong supporter of the French Revolution. In 1794 Coleridge met Robert Southey and the two men became close friends.

Coleridge and Southey developed radical political and religious views and began making plans to emigrate to Pennsylvania where they intended to set up a commune based on communistic values. Coleridge and Southey eventually abandoned this plan and instead stayed in England where they concentrated on communicating their radical ideas. This included the play they wrote together, The Fall of Robespierre.

In 1795 Coleridge and Robert Southey married two sisters, Sarah and Edith Flicker. Samuel and Sarah Coleridge moved to Bristol where he lectured at Unitarian chapels and wrote over fifty articles for the Morning Chronicle that gave him the opportunity to explain the ideas of Joseph Priestley and William Godwin to a large audience. The Morning Chronicle also published Coleridge's anti-war poem, Fire, Famine, Slaughter: A War Eclogue. Coleridge also edited the radical Christian journal, The Watchman.

In 1797 Coleridge met William Wordsworth. Together the two men developed a new poetry. The following year they published the book Lyrical Ballads which achieved a revolution in literary taste and sensibility. This included Coleridge's famous poems, the Ancient Mariner and The Nightingale. For the next few years Coleridge concentrated on writing poetry but an addiction to opium damaged the quality of his work.

Coleridge retained an interest in journalism and in 1809 began publishing his own newspaper, The Friend. This "literary, moral and political" newspaper came to an end after only 28 issues. He returned to poetry and in 1816 published Christabel and Kubla Khan.

Coleridge's writing during this period about what had gone wrong with society had a considerable influence on Christian Socialists such as Frederick Maurice and Charles Kingsley. However, Coleridge's articles in support of Lord Liverpool and his Tory government in The Courier caused William Hazlitt to denounce him as a "turncoat".

In his later years Coleridge wrote several important books on literature including Biographia Literaria (1817) and Aids to Reflection (1825). Coleridge's later ideas that were revealed in conversations with friends, were collected together and edited by his nephew Henry Coleridge and appeared in the book Table Talk in 1836.

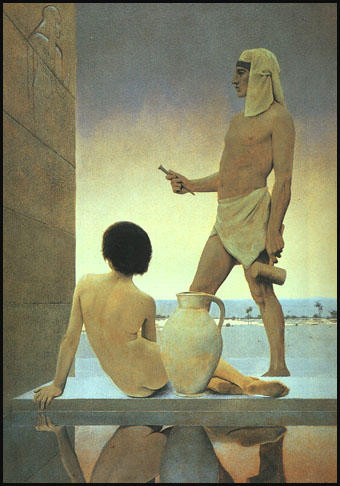

On this day in 1870 artist Maxfield Parrish, the son of the painter, Stephen Parrish, was born in Philadelphia. He was educated at the Haverford College, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the Drexel Institute, where he studied under Howard Pyle.

After his marriage to Lydia Austin he settled in Plainfield, New Hampshire. In 1895 Parrish designed his first cover for Harper's Weekly. As well as working for other magazines such as Collier's and Scribner's Magazine.

Parrish also provided the illustrations for a large number of books including Poems of Childhood (1889), Mother Goose in Prose (1897), Dream Days (1906), Tanglewood Tales (1910), The Golden Treasury of Songs and Lyrics (1911) and The Knave of Arts (1925).

Parrish provided the art work for posters and advertisements. His greatest success came with colour prints designed for the mass market. The Garden of Allah (1919) and Dawn (1920) sold in very large numbers. In the 1920s Parrish concentrated on fine art painting. Several of these works featured Susan Lewin. She had been initially hired at the age of 16 as a nanny. She eventually became his mistress and his wife left the family home.

In the 1930s Parrish's work, criticised as being too sentimental, went out of fashion. In 1931, he commented, "I'm done with girls on rocks", and decided to concentrate on landscapes. Though never as popular as his earlier works, he profited from them.

Maxfield Parrish died at the age of 95 on 30th March 1966.

On this day in 1909 Louis Blériot makes the first flight across the English Channel in a heavier-than-air machine from Calais to Dover. Alfred Harmsworth, the owner of the Daily Mail, was a great supporter of flying and in October, 1908, offered a prize of £1,000 for the first airman to cross the English Channel from Calais to Dover. The idea seemed so preposterous that Punch Magazine decided to poke fun at Harmsworth by offering a prize of £10,000 for the first flight to Mars.

Blériot decided he would make an attempt at winning the prize. He now began work on a new plane, the Blériot XI. It made its first flight on 23rd January, 1909, and early tests showed this was a remarkable aircraft. On 25th July, 1909, Blériot took off from Les Baraques, near Calais, at 4.41am. After covering a distance of almost 24 miles (36.6 km) he arrived at Northfall Meadow, near Dover, at 5.17 am. One man wrote "England's isolation has ended once and for all."

As a result of his achievement Blériot was able to sell the Blériot XI to the French Army. It was also sold to other countries and first saw action during the Italo-Turkish War (23rd October, 1911).

In 1914 Blériot became president of the aircraft company Société pour les Appareils Deperdussin. He renamed the company Société Pour Aviation et ses Derives (SPAD) and turned it into one of France's leading manufacturers of combat aircraft.

The Spad S.XIII appeared in 1917 and soon established itself as the best fighter plane available. Leading Allied aces such as Rene Fonck, Georges Guynemer, Charles Nungesser and Edward Rickenbacker insisted on using this aircraft. It has been argued that the Spad S.XIII was the main reason why the Allies gained control over the skies on the Western Front during 1918. A total of 8,472 of these aircraft were used during the First World War.

After the war, Blériot formed his own company, Blériot-Aéronautique, Aéronautique for the development of commercial aircraft. Louis Blériot died on 2nd August, 1936.

On this day on 1920 scientist Rosalind Franklin was born in London. She attended St. Paul's Girls' School and became aware of the international political situation when her parents took in two Jewish children from Nazi Germany to live in their home as part of the family. Rosalind shared her room with Evi Eisenstrdter whose father had been sent to Buchenwald a Concentration Camp in Germany.

Rosalind studied chemistry and physics at Newnham College, Cambridge, and in 1942 began carrying out research at the British Coal Utilization Research Association. Over the next four years she helped develop carbon fibre technology.

In 1947 Rosalind went to the Central Government Laboratory for Chemistry in Paris where she worked on X-ray diffraction until 1951 when she moved to King's College, London. Rosalind produced X-ray diffraction pictures of DNA which were published in Nature in April 1953. This played an important role in establishing the structure of DNA.

Rosalind came into conflict with Maurice Wilkins, who was also working on DNA at King's College, and therefore decided to join John Bernal at Birkbeck College to carry out research into the tobacco mosaic virus. In 1957 Rosalind began to work on the polo virus.

Rosalind Franklin died of ovarian cancer on 16th April 1958.

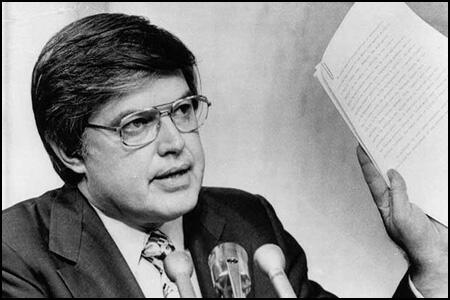

On this day in 1924 Frank Church was born in Boise, Idaho. While at school Church became a strong supporter of William Borah. At Boise High School, Church won the 1941 American Legion National Oratorical Contest with a speech titled "The American Way of Life."

In 1942 Church became a student at Stanford University but the following year he joined the United States Army and during the Second World War served as a military intelligence officer in Burma.

After the war he returned to Stanford University and after graduating in 1950 he began work as a lawyer in Boise. Church joined the Democratic Party and in 1956 he was elected to the Senate. He was only 32 years old and was the fifth youngest member ever to sit in the Senate.

In 1959, Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson appointing Church to the Foreign Relations Committee. Church, like his idol, William Borah, held independent political views and in 1965, Church began to criticize U.S. involvement in Vietnam. In 1969, he joined with Senator John Sherman Cooper to sponsor an amendment prohibiting the use of ground troops in Laos and Thailand. The two men also joined forces in 1970 to limit the power of the president during a war.

Frank Church served on several Senate committees including the Special Committee on Aging, Special Committee on Termination of the National Emergency and Select Committee on Government Intelligence Activities. In 1975, Church became the chairman of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities. This committee investigated alleged abuses of power by the Central Intelligence Agency and the Federal Bureau of Intelligence.

The committee looked at the case of Fred Hampton and discovered that William O'Neal, Hampton's bodyguard, was a FBI agent-provocateur who, days before the raid, had delivered an apartment floor-plan to the Bureau with an "X" marking Hampton's bed. Ballistic evidence showed that most bullets during the raid were aimed at Hampton's bedroom.

Church's committee also discovered that the Central Intelligence Agency and Federal Bureau of Investigation had sent anonymous letters attacking the political beliefs of targets in order to induce their employers to fire them. Similar letters were sent to spouses in an effort to destroy marriages. The committee also documented criminal break-ins, the theft of membership lists and misinformation campaigns aimed at provoking violent attacks against targeted individuals.

One of those people targeted was Martin Luther King. The FBI mailed King a tape recording made from microphones hidden in hotel rooms. The tape was accompanied by a note suggesting that the recording would be released to the public unless King committed suicide.

In 1975 Church's committee interviewed Johnny Roselli about his relationship with the secret services. It emerged that in In September 1960, Roselli and fellow crime boss, Sam Giancana, took part in talks with Allen W. Dulles, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), about the possibility of murdering Fidel Castro.

In its final report the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities concluded: “Domestic intelligence activity has threatened and undermined the Constitutional rights of Americans to free speech, association and privacy. It has done so primarily because the Constitutional system for checking abuse of power has not been applied.”

According to the Congress report published in 1976: "The CIA currently maintains a network of several hundred foreign individuals around the world who provide intelligence for the CIA and at times attempt to influence opinion through the use of covert propaganda. These individuals provide the CIA with direct access to a large number of newspapers and periodicals, scores of press services and news agencies, radio and television stations, commercial book publishers, and other foreign media outlets." Church argued that the cost of misinforming the world cost American taxpayers an estimated $265 million a year.

Church showed that it was CIA policy to use clandestine handling of journalists and authors to get information published initially in the foreign media in order to get it disseminated in the United States. Church quotes from one document written by the Chief of the Covert Action Staff on how this process worked (page 193). For example, he writes: “Get books published or distributed abroad without revealing any U.S. influence, by covertly subsidizing foreign publicans or booksellers.” Later in the document he writes: “Get books published for operational reasons, regardless of commercial viability”. Church goes onto report that “over a thousand books were produced, subsidized or sponsored by the CIA before the end of 1967”. All these books eventually found their way into the American market-place. Either in their original form (Church gives the example of the Penkovskiy Papers) or repackaged as articles for American newspapers and magazines.

In another document published in 1961 the Chief of the Agency’s propaganda unit wrote: “The advantage of our direct contact with the author is that we can acquaint him in great detail with our intentions; that we can provide him with whatever material we want him to include and that we can check the manuscript at every stage… (the Agency) must make sure the actual manuscript will correspond with our operational and propagandistic intention.”

Church quotes Thomas H. Karamessines as saying: “If you plant an article in some paper overseas, and it is a hard-hitting article, or a revelation, there is no way of guaranteeing that it is not going to be picked up and published by the Associated Press in this country” (page 198).

By analyzing CIA documents Church was able to identify over 50 U.S. journalists who were employed directly by the Agency. He was aware that there were a lot more who enjoyed a very close relationship with the CIA who were “being paid regularly for their services, to those who receive only occasional gifts and reimbursements from the CIA” (page 195).

Church pointed out that this was probably only the tip of the iceberg because the CIA refused to “provide the names of its media agents or the names of media organizations with which they are connected” (page 195). Church was also aware that most of these payments were not documented. This was the main point of the Otis Pike Report. If these payments were not documented and accounted for, there must be a strong possibility of financial corruption taking place. This includes the large commercial contracts that the CIA was responsible for distributing. Pike’s report actually highlighted in 1976 what eventually emerged in the 1980s via the activities of CIA operatives such as Edwin Wilson, Thomas Clines, Ted Shackley, Raphael Quintero, Richard Secord and Felix Rodriguez.

Church also identified E. Howard Hunt as an important figure in Operation Mockingbird. He points out how Hunt arranged for books to be reviewed by certain writers in the national press. He gives the example of how Hunt arranged for a “CIA writer under contract” to write a hostile review of a Edgar Snow book in the New York Times (page 198).

Church concluded that: “In examining the CIA’s past and present use of the U.S. media, the Committee finds two reasons for concern. The first is the potential, inherent in covert media operations, for manipulating or incidentally misleading the American public. The second is the damage to the credibility and independence of a free press which may be caused by covert relationships with the U.S. journalists and media organizations.”

The committee also reported that the Central Intelligence Agency had withheld from the Warren Commission, during its investigation of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, information about plots by the Government of the United States against Fidel Castro of Cuba; and that the Federal Bureau of Investigation had conducted a counter-intelligence program (COINTELPRO) against Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

The Mafia boss, Sam Giancana was ordered to appear before the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities. However, before he could appear, on 19th June, 1975, Giancana was murdered in his own home. He had a massive wound in the back of the head. He had also been shot six times in a circle around the mouth. At the same time Jimmy Hoffa, another man the committee wanted to interview, also disappeared. His body was never found.

Johnny Roselli was also due to appear before Church's committee when he was murdered and in July 1976 his body was found floating in an oil drum in Miami's Dumfoundling Bay. Jack Anderson, of the Washington Post, interviewed Roselli just before he was killed. On 7th September, 1976, the newspaper reported Roselli as saying : "When Oswald was picked up, the underworld conspirators feared he would crack and disclose information that might lead to them. This almost certainly would have brought a massive U.S. crackdown on the Mafia. So Jack Ruby was ordered to eliminate Oswald."

As a result of Church's report and the deaths of Sam Giancana, Jimmy Hoffa and Johnny Roselli, Congress established the House Select Committee on Assassinations in September 1976. The resolution authorized a 12-member select committee to conduct an investigation of the circumstances surrounding the deaths of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King.

In 1976 Church sought the nomination for the Democratic candidacy for president. He won primaries in Nebraska, Idaho, Oregon and Montana, but eventually decided to withdraw in favor of Jimmy Carter.

Church's outspoken views made him a lot of enemies and in 1980 was defeated in his attempt to be elected to the Senate for a fifth term.

Frank Church was appointed United States delegate to the 21st General Assembly of the United Nations. Afterwards he worked in Washington for the international law firm of Whitman and Ransom.

Frank Church died from a pancreatic tumor on 7th April, 1984.

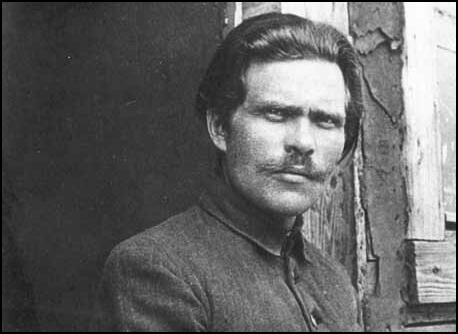

On this day in 1934 Nestor Makhno died of tuberculosis. .

Nestor Makhno, the son of peasants, was born in Hulyai-Pole, Ukraine, on 27th October 1889. His father died the following year and at the age of seven he was put to work tending cows and sheep for local peasants. Later he found employment as a farm labourer.

In 1906, at the age of seventeen, Makhno joined an anarchist group and became involved in terrorist activities. Two years later he was arrested and sentenced to death but was reprieved because of his youth and imprisoned in Butyrki Prison in Moscow.

Makhno was initially placed in irons or in solitary confinement. Later he shared a cell with an older, more experienced anarchist named Peter Arshinov, who had been imprisoned for smuggling arms from Austria. Over the next few years he taught him about the libertarian doctrine that had been developed by Michael Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin.

Makhno was released from prison after the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II. Makhno later recalled: "The February Revolution of 1917 opened the gates of all Russian prisons for political prisoners. There can be no doubt this was mainly brought about by armed workers and peasants taking to the streets, some in their blue smocks, others in grey military overcoats. These revolutionary workers demanded an immediate amnesty as the first conquest of the Revolution.... The tsarist government of Russia, based on the landowning aristocracy, had walled up these political prisoners in damp dungeons with the aim of depriving the labouring classes of their advanced elements and destroying their means of denouncing the iniquities of the regime. Now these workers and peasants, fighters against the aristocracy, again found themselves free. And I was one of them."

Makhno returned to his native village and assumed a leading role in community affairs. In August 1917 he was elected as chairman of the Hulyai-Pole Soviet of Workers' and Peasants. He now recruited a band of armed men and set about expropriating the estates of the neighboring gentry and distributing the land to the peasants. After the Russian Revolution he became one of the leaders in the area.

After the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk the German Army marched into the Ukraine. His band of partisans was too weak to offer effective resistance and Makhno was forced to go into hiding. He arrived in Moscow in June 1918. Makhno had a meeting with his hero, Peter Kropotkin, who had arrived in Russia from his long-period in exile.

Nestor Makhno also had a meeting with Lenin in the Kremlin. Lenin explained his opposition to anarchists. "The majority of anarchists think and write about the future without understanding the present. That is what divides us Communists from them... But I think that you, comrade, have a realistic attitude towards the burning evils of the time. If only one-third of the anarchist-communists were like you, we Communists would be ready, under certain well-known conditions, to join with them in working towards a free organization of producers." Makhno answered that the anarchists were not utopian dreamers but realistic men of action.

Makhno returned to the Ukraine in July 1918. The area was still occupied by Austrian troops that had installed a puppet ruler, Pavlo Skoropadskyi. Makhno launched a series of raids against the government and the manors of the nobility. As Paul Avrich has pointed out: "Previously independent guerrilla bands accepted Makhno's command and rallied behind his black banner. Villagers provided food and fresh horses, enabling the Makhnovists to travel forty or fifty miles a day with little difficulty. Turning up quite suddenly where least expected, they would attack the gentry and military garrisons, then vanish as quickly as they had come. In captured uniforms they infiltrated the enemy's ranks to learn their plans or to open fire at point-blank range. On one occasion, Makhno and his retinue, masquerading as Hetmanite guardsmen, gained entry to a landowner's ball and fell upon the guests in the midst of their festivities. When cornered, the Makhnovists would bury their weapons, make their way singly back to their villages, and take up work in the fields, awaiting a signal to unearth a new cache of arms and spring up again in an unexpected quarter."

Isaac Babel, a political commissar in the Red Army in the Ukraine wrote: "Makhno was as protean as nature herself. Haycarts deployed in battle array take towns, a wedding procession approaching the headquarters of a district executive committee suddenly opens a concentrated fire, a little priest, waving above him the black flag of anarchy, orders the authorities to serve up the bourgeoisie, the proletariat, wine and music."

Victor Serge argued: "Nestor Makhno, boozing, swashbuckling, disorderly and idealistic, proved himself to be a born strategist of unsurpassed ability. The number of soldiers under his command ran at times into several tens of thousands. His arms he took from the enemy. Sometimes his insurgents marched into battle with one rifle for every two or three men: a rifle which, if any soldier fell, would pass at once from his still-dying hands into those of his alive and waiting neighbour."

Makhno always had a large black flag, the symbol of anarchy, at the head of his army, embroidered with the slogans "Liberty or Death" and "the Land to the Peasants, the Factories to the Workers". Makhno later told Emma Goldman that his objective was to establish a libertarian society in the south that would serve as a model for the whole of Russia. When he set-up his first commune near Pokrovskoye, he named it in honour of Rosa Luxemburg.

In September 1918, after defeating a large force of Austrians at the village of Dibrivki, his men gave him the title, "little father". Two months later the First World War came to an end and all foreign troops left Russia. Pavlo Skoropadskyi was removed from power in an uprising led by Symon Petliura. With the support of the Red Army, Makhno was able to force Petliura into exile.

According to Emma Goldman, she was told by a person living in the Ukraine that "there grew up among the country folk the belief that Makhno was invincible because he had never been wounded during all the years of warfare in spite of his practice of always personally leading every charge."

In 1919, Nestor Makhno married Agafya Kuzmenko, a former elementary schoolteacher (1892-1978), who also served as one of his aides. They had one daughter, Yelena. Two of Makhno's brothers were members of his army before being captured in battle and executed by firing squad.

A pact for joint military action against General Anton Denikin and his White Army was signed in March 1919. However, the Bolsheviks did not trust the anarchists and two months later two Cheka agents sent to assassinate Makhno were caught and executed. Leon Trotsky, commander-in-chief of the Bolsheviks forces, ordered the arrest of Makhno and sent in troops to Hulyai-Pole dissolve the agricultural communes set up by the Makhnovists. With Makhno's power undermined, a few days later, Denikin forces arrived and completed the job, liquidating the local soviets as well.

On 26th September 1919, Makhno launched a successful counterattack at the village of Peregonovka, cutting Denikin's supply lines. This was followed by a new offensive by the Red Army and Denikin's White Army was forced to retreat to the shores of the Black Sea.

Leon Trotsky now turned to dealing with the anarchists and outlawed the Makhnovists. According to the author of Anarchist Portraits (1995): "There ensued eight months of bitter struggle, with losses heavy on both sides. A severe typhus epidemic augmented the toll of victims. Badly outnumbered, Makhno's partisans avoided pitched battles and relied on the guerrilla tactics they had perfected in more than two years of civil war."

A truce was called in October 1920, when General Peter Wrangel and his White Army launched a major offensive in the Ukraine. Trotsky offered to release all anarchists in Russian prison in return for joint military action against Wrangel. However, once the Red Army made sufficient gains to ensure victory in the Civil War, the Makhnovists were once again outlawed. On 25th November, 1920, Makhno's commanders in the Crimea, who had just defeated Wrangel's forces, were seized by the Red Army and executed.

Leon Trotsky now gave orders for an attack on Makhno's headquarters in Hulyai-Pole. Most of his staff were captured and shot but Makhno managed to escape with the remnant of his army. After wandering over the Ukraine for nearly a year, Makhno, suffering from unhealed wounds, crossed the Dniester River into Rumania where he was arrested and interned. He escaped to Poland but was once again arrested and imprisoned in Danzig. Eventually, aided by Alexander Berkman, he was allowed to move to Paris.

Leon Trotsky attempted to explain why he had given orders for Makhno to be assassinated: "Makhno... was a mixture of fanatic and adventurer... Makhno created a cavalry of peasants who supplied their own horses. They were not downtrodden village poor whom the October Revolution first awakened, but the strong and well-fed peasants who were afraid of losing what they had. The anarchist ideas of Makhno (the ignoring of the State, non-recognition of the central power) corresponded to the spirit of the kulak cavalry as nothing else could."

In 1926 Makhno joined forces broke with Peter Arshinov to publish their controversial Organizational Platform, which called for a General Union of Anarchists. This was opposed by Vsevolod Volin, Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Sébastien Faure and Rudolf Rocker, who argued that the idea of a central committee clashed with the basic anarchist principle of local organisation.

Nestor Makhno was unhappy in Paris saying he hated the "poison" of big cities, and missed the landscape of Hulyai-Pole. According to Alexander Berkman he talked of returning home and "taking up the struggle for liberty and social justice." However, as Paul Avrich points out that he "lived his remaining years in obscurity, poverty, and disease, an Antaeus cut off from the soil that might have replenished his strength."

Nestor Makhno died of tuberculosis on 6th July 1935.

On this day in 1941 Emmett Till, the only child of Louis Till and Mamie Till, was born near Chicago, Illinois, on 25th July, 1941. At the age of three he became ill with non paralytic polio. He survived but left him with a speech defect. Friends described him as "brash, prank-loving" who "liked to dress smart and talk smart".

Mamie and Louis Till separated in 1942 after she discovered that he had been unfaithful. Louis later abused her, choking her to, unconsciousness, to which she responded by throwing scalding water at him. For violating court orders to stay away from Mamie, Louis Till was forced by a judge in 1943 to choose between jail or enlisting in the U.S. Army.

While taking part in the Italian Campaign, Till, Fred A. McMurray and an unnamed soldier, were arrested by military police, who suspected them of the murder of an Italian woman and the rape of two others, in Civitavecchia. The third third soldier was granted immunity in exchange for testimony against McMurray and Till. After a short investigation, Till and McMurray were court-martialed, found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was carried out on 2nd July, 1945.

According to Juan Williams, "Emmett Till's neighborhood was a working-class black area with its share of storefront preachers and apartment buildings crowded with relatives from Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi... Emmett Till knew segregation. McCosh Elementary was a public school with black students only. When his mother, made plans to send him south for the summer on the Illinois Central, she knew he would have to ride in the train's colored section. But the segregation Emmett knew in the North was nothing like the segregation he rode into in Mississippi. His only warning came from his mother, a Mississippi native who had left for Chicago with her family when she was two years old." Mamie Till warned her son to be careful when dealing with white people in Mississippi: "If you have to get on your knees and bow when a white person goes past, do it willingly."

In August, 1955, Emmett, now aged 14, was sent by his mother to visit relatives near Money, Mississippi. Emmett stayed at the home of his uncle, Moses Wright. During the evening of 24th August, Emmett, Simeon Wright, and a group of his friends, went to Bryant's Grocery Store. Carolyn Bryant later claimed that Emmett had grabbed her at the waist and asked her for a date. When pulled away by his cousin, Emmett allegedly said, "Bye, baby" and "wolf whistled".

Wright later commented: "I think Emmett wanted to get a laugh out of us or something. He was always joking around, and it was hard to tell when he was serious.... Well, it scared us half to death. You know, we were almost in shock. We couldn't get out of there fast enough, because we had never heard of anything like that before. A black boy whistling at a white woman? In Mississippi? No."

Carolyn Bryant told her husband, Roy Bryant, about the incident and he decided to punish the boy for his actions. The following Saturday, Roy Bryant and his half-brother, John W. Milam, took him from the home of Moses Wright and drove him to "a barn, beat and lynched him. They dragged his body to the Tallahatchie River, shot him in the head, tied him with barbed wire to a massive metal cotton gin fan, and shoved his body into the water."

After Emmett's body was found Bryant and Milam were charged with murder. On 19th September, 1955, the trial began in a segregated courthouse in Sumner, Mississippi. Joseph Wilson Kellum was their defence attorney. He later recalled that he believed the men when they denied that they had murdered Till. During the trial he told the jury that their forefathers would turn over in their graves if they convicted any white man for killing a black man. "I was trying to say something that would meet with - where they would agree with me, you see. Because I was employed to defend those fellas. And I was going to defend them as much as I could and stay within the law."

In court Moses Wright identified Bryant and Milam as the two men who took away his nephew on the 24th August. Moses pleaded with the men to leave Emmett alone. "He's only 14, he's from up North. Why not give the boy a whipping, and leave it at that?" His wife Elizabeth Wright offered money to the intruders, but they ordered her to go back to bed. Milam, at 6 feet two inches and 235 pounds, turned to Moses and threatened him. "How old are you, preacher?" Wright said that he was 64. "If you make any trouble, you'll never live to be 65."

Other African Americans also gave evidence against Bryant and Milam but after four days of testimony the all white jury took just 67 minutes to return a not-guilty verdict. "One of the jurors said they would have returned earlier if they had not stopped for a soda." After the trial Moses Wright, fearing what would happen to him if he remained in Mississippi, moved to Chicago.

Richard Rubin interviewed one of the jurors, Ray Tribble, many years after the trial. Rubin asked him why he found the men not guilty. He agreed with Kellum that the whole event had been staged by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and that Emmett Till was still alive. "He explained, quite simply, that he had concurred with the defense team's core argument: that the body fished out of the Tallahatchie River was not that of Emmett Till - who was, they claimed, still very much alive and hiding out in Chicago or Detroit or somewhere else up North - but someone else's, a corpse planted there by the NAACP for the express purpose of stirring up a racial tornado that would tear through Sumner, and through all of Mississippi, and through the rest of the South, for that matter." Rubin pointed out Emmett Till's own mother identified the body of her son? Tribble replied: "That body had hair on its chest... and everybody knows that "blacks don't grow hair on their chest until they get to be about 30."

Mississippi senators James Eastland and John C. Stennis were leaked information about the crimes of Emmett's father, Louis Till. News about this was carried on the front pages of Mississippi newspapers throughout October and November 1955. According to Davis Houck and Matthew A. Grindy, the authors of Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press (2008), "Louis Till became a most important rhetorical pawn in the high-stakes game of north versus south, black versus white, NAACP versus White Citizens' Councils".

The Chicago Defender, took a very different approach to its reporting of the case and called on the federal government to take action: "The trial is over, and this miscarriage of justice must not be left unavenged. The Defender will continue its investigations, which helped uncover new witnesses in the case, to find other Negroes who actually witnessed the lynching, before they too are found in the Tallahatchie river. At this point we can only conclude that the administration and the justice department have decided to uphold the way of life of Mississippi and the South. Not only have they been inactive on the Till case, but they have yet to take positive action in the kidnapping of Mutt Jones in Alabama, who was taken across the state line into Mississippi and brutally beaten. And as yet the recent lynchings of Rev. George Lee and LaMarr Smith in Mississippi have gone unchallenged by our government. The citizens councils, the interstate conspiracy to whip the Negro in line with economic reins, open defiance to the Supreme Court's school decision - none of these seem to be violations of rights that concern the federal government."

The authorities in Mississippi wanted to bury Emmett Till straight away. However, Mamie Till insisted on taking her son's body back to Chicago. "Do you want me to fix him up?" the undertaker asked her. "No, you can't fix that. Let the world see what I saw." Her decision to leave the coffin open and delay the funeral by three days exposed the rest of America and the world to what was happening in Mississippi. Thousands in Chicago lined up to see the body and the pictures were published in the black magazine Jet.

Aware they could not be tried again for the murder of Emmett Till, Roy Bryant and John Milam decided to sell their story for around $4,000. The journalist, William Bradford Huie, decided to pay this money. The interview took place in the law firm of the attorneys who had defended Bryant and Milam. Bryant and Milam's attorneys asked the questions and both men confessed to killing Till. They attempted to justify the murder by claiming they only wanted to scare him. However, when he refused to repent or beg for mercy, they said, they had to kill him.

Huie's article was published in Look Magazine in January 1956, He quoted Milam as saying: "Well, what else could we do? He was hopeless. I'm no bully; I never hurt a N******* in my life. I like N******* in their place -- I know how to work 'em. But I just decided it was time a few people got put on notice. As long as I live and can do anything about it, N******* are gonna stay in their place. N******* ain't gonna vote where I live. If they did, they'd control the government. They ain't gonna go to school with my kids. And when a N******* gets close to mentioning sex with a white woman, he's tired o' livin'. I'm likely to kill him. Me and my folks fought for this country, and we got some rights. I stood there in that shed and listened to that N******* throw that poison at me, and I just made up my mind. 'Chicago boy,' I said, 'I'm tired of 'em sending your kind down here to stir up trouble. Goddam you, I'm going to make an example of you - just so everybody can know how me and my folks stand.'"

This confession had a tremendous impact on the consciousness of many people living in the Deep South. Anne Moody wrote: "Before Emmett Till's murder, I had known the fear of hunger, hell, and the Devil. But now there was a new fear known to me - the fear of being killed just because I was black. This was the worst of my fears. I knew once I got food, the fear of starving to death would leave. I also was told that if I were a good girl, I wouldn't have to fear the Devil or hell. But I didn't know what one had to do or not do as a Negro not to be killed. Probably just being a Negro period was enough, I thought. I was fifteen years old when I began to hate people. I hated the white men who murdered Emmett Till and I hated all the other whites who were responsible for the countless murders Mrs. Rice (my teacher) had told me about and those I vaguely remembered from childhood. But I also hated Negroes. I hated them for not standing up and doing something about the murders. In fact, I think I had a stronger resentment toward Negroes for letting the whites kill them than toward the whites."

Mamie Till joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and agreed to travel and lecture throughout the country. "Two months ago I had a nice apartment in Chicago. I had a good job. I had a son. When something happened to the Negroes in the South I said, 'That's their business, not mine'. Now I know how wrong I was. The murder of my son has shown me that what happens to any of us, anywhere in the world, had better be the business of us all."

The Montgomery Advertiser picked up the story and wrote about it in some detail. It condemned the reporting of the case, especially the detailed account of the crimes committed by Emmett's father, Louis Till. Elliott J. Gorn has pointed out: The image of Emmett Till as a sexual assailant seemed much more plausible if Louis Till was a 'savage murderer and rapist'. No one had to speak any of this; such ideas were just below the surface, deeply held, easily stirred."

Juan Williams, the author of Eyes on the Prize: America's Civil Rights Years: 1954-1965 (1987) has argued that there is a strong connection between the reporting of the lynching of Emmett Till and the fact that a few months later Rosa Parks led the black population of Montgomery to boycott of their municipal bus system. As Martin Luther King, a pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, agreed to help organise the Montgomery Bus Boycott the Till murder can be seen as the start of the modern civil rights movement.

Elliott J. Gorn, agrees with this assessment. In his book, Let the People See: The Emmett Till Story (2018) he argues that their is a link between the death of Till and Little Rock High School, Segregated Lunch Counters and The Selma March: "The Emmett Till generation carried his memory into Montgomery, Little Rock, Greensboro, Birmingham, Selma, and countless other places where they marched and demonstrated."

In the late 1990s the filmmaker Keith Beauchamp began investigating the Emmett Till case. According to the The New York Times "he interviewed several potential witnesses, including one who was jailed in another city at the time of the trial to keep investigators from calling him to the stand... Beauchamp now asserts that there were actually 10 people - several of them still alive - present at the murder."

At the trial Carolyn Bryant testified that Emmett Till had grabbed her hand, she pulled away, and he followed her behind the counter, clasped her waist, and, using vulgar language, told her that he had been with white women before." In an interview she gave to Timothy B. Tyson, a Duke University professor in 2016: "She said that wasn't true, but that she honestly doesn't remember exactly what did happen."

In 2022 a team searching a Mississippi courthouse basement for evidence about the lynching of Emmett Till found the unserved warrant charging Carolyn Bryant in his 1955 kidnapping. The Emmett Till Legacy Foundation responded by demanding that the authorities finally arrest her this offence. Apparently, the Leflore County sheriff told reporters in 1955 he did not serve the warrant because he did not want to "bother" the woman since she had two young children to care for.

In July 2020, Carolyn Bryant Donham, published a memoir of her life, I Am More Than A Wolf Whistle (2020) "It is my fervent desire that my story will shed light on what happened, at least as I knew and remembered it, and illuminate my small part in this tragedy." Her story had changed from the interview she gave in 2016 and returned to the version she told in 1955 and accused Emmett Till of sexual assault. "He came in our store and put his hands on me with no provocation."

However, she claimed she tried to protect him when her husband and brother-in-law brought him to her home that night. "I did not wish Emmett any harm and could not stop harm from coming to him, since I didn't know what was planned for him. I tried to protect him by telling Roy that ‘He's not the one. That's not him. Please take him home... To my utter disbelief, the young man flashed me a strange smile and said, ‘Yes, it was me,' or something to that effect." Davis Houck, co-author of Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press (2008), has argued: "The idea that Till would essentially out himself in front of his kidnappers and would-be killers," he said, "is beyond absurd."

Bryant insisted that when they left her home she was convinced the men would take Emmett Till home. "The three of them left the store with the young man walking in between. I really wanted to believe he was going to take him back home. I melted into the kitchen chair like a limp doll when they left the room. I heard Roy tell J.W. and his friend to take him back home. I knew that he would be okay; shaken up maybe, scared but okay."

Many people were highly critical of her account: "I always felt like a victim as well as Emmett.... Did we both pay a price for it, yes, we did. He paid dearly with the loss of his life. I paid dearly with an altered life... I have always prayed that God would bless Emmett's family. I am truly sorry for the pain his family was caused. the filmmaker Keith Beauchamp said the memoir shows that Bryant "is culpable in the kidnapping and murder of Emmett Louis Till and to not hold her accountable for her actions, is an injustice to us all."

Dale Killinger, a retired FBI agent who investigated the case more than 15 years ago commented: "For instance, Donham claims in the memoir to have yelled for help after being confronted by Till inside the family grocery store in Money, Mississippi, yet no one ever reported hearing her screams" Killinger said. Also, Donham never previously mentioned that she and Roy Bryant chatted about the abduction. In the manuscript, she says they did. "That seems ludicrous," Killinger said. "How would you have a major event in your life and not talk about it?"

Killinger points out that during his interviews with Donham, Killinger said she "stated on multiple occasions that she and Roy never discussed the kidnapping and murder." But her memoir tells a different story. After the sheriff showed up in 1955, Donham said Bryant told her in the kitchen that "they had only ‘whipped Emmett' and let him go, so not to worry because everything would be okay." She said she later confronted Bryant about the 14-year-old's death, asking, "How could you do such a thing?" Bryant denied killing Till, and she said she replied, "But you are guilty. You could have walked away, but you didn't. You could have stopped it, but you didn't."

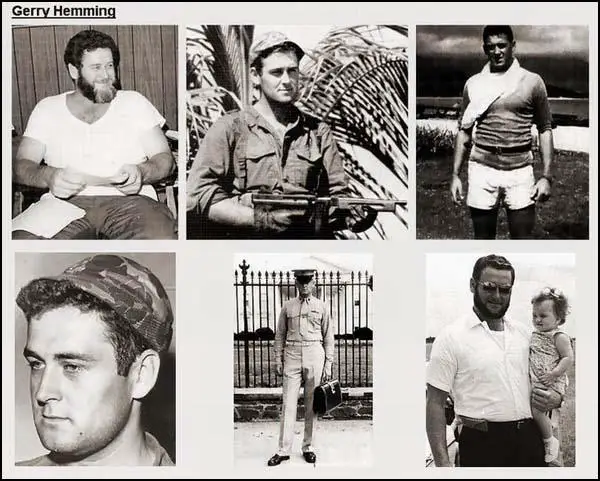

On this day on 1967 Thomas Bethell writes letter to Edward Jay Epstein about a visit from Gerald Patrick Hemming, the leader of Interpen and told him about the assassination of John F. Kennedy .

We were recently paid an unannounced visit by two Americans who were intimately connected with Cuban exile groups in the summer of 1963. One, Gerry Patrick Hemming, was even dressed in fatigues. The main purpose of their visit seemed to be to point an authoritative finger of suspicion at Hall, Howard and Seymour, (to an extent that we began to wonder if they knew that others were involved and were trying to protect them.) Gerry Patrick told me the following story which I thought might interest you.

According to Gerry Patrick, (he usually drops the Hemming) there were in 1963 numerous "teams" with paramilitary inclinations out to "get" Kennedy. Some of these teams had been approached by wealthy entrepreneurs of the H.L. Hunt type, (though not, I think, in fact H.L. Hunt) who were interested in seeing the job done and even provided financial assistance. Then, on November 22, 1963, Kennedy is shot down on the streets, ("Maybe Oswald got there ahead of them," Patrick commented) and then for 2 years or so, there the story rests.

However, since all the mounting controversy of the last 12 months, a startling new development has occurred, according to Patrick. Recently, members of the "teams" have been returning to their sponsors, taking credit for the assassination, and at the same time requesting large additional sums of money so that they won't be tempted to talk about it to anyone. In turn, the sponsors have apparently been hiring Mafia figures to rid themselves of these blackmailers.

Gerry Patrick admitted that his own association with some of these extremist groups in 1963 has recently been causing him some concern. Incidentally, this may very well be the true story behind the Del Valle murder in Miami, reported this spring in the National Enquirer.

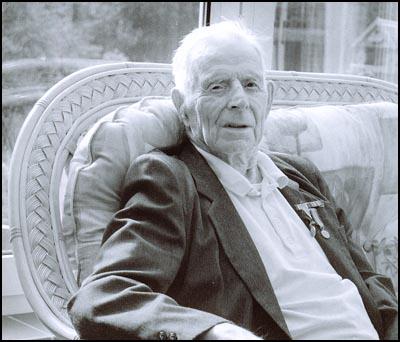

On this day in 2009 First World War veteran Harry Patch died aged 111.

Henry (Harry) Patch, the son of a stonemason, was born in Bath, on 17th June 1898. He attended Coombe Down School and later recalled: "I was fifteen when I left, but I continued to study afterwards. At eighteen I sat for the registered plumber's certificate."

Patch's older brother was in the Royal Engineers and took part in the early stages of the First World War. He was badly wounded at Mons and was invalided out of the army. "He told me what the trenches were like, and I didn't want to go."

Harry Patch was conscripted in October 1916. After six months at Sutton Vealey with the 33rd Training Battalion, he was sent to the Western Front where he was put on the Lewis Gun. "I'll always remember morning inspection in the trenches. That was very severe. They used to come round and your gun had to be clean, well oiled and loaded."

In June 1917 Patch was promoted to the rank of lance corporal in the Cornwall's Light Infantry. He was at Passchendaele but did not go over the top until a few weeks later at Pilckem Ridge. "I can still see the bewilderment and fear on the men's faces as we went over the top. We crawled because if you stood up you'd be killed. All over the battlefield the wounded were lying there, English and German, all crying for help."

Patch later described how one German attacked his Lewis Gun. "He couldn't have had any ammunition or he would have shot me, but he came towards me with his bayonet pointing at my chest. I fired and hit him in the shoulder. He dropped his rifle, but still came stumbling on. I can only suppose that he wanted to kick our Lewis Gun into the mud, which would have made it useless. I had three live rounds left in my revolver and could have killed him with the first. What should I do? I had seconds to make my mind up. I gave him his life. I didn't kill him. I shot him above the ankle and above the knee and brought him down. I knew he would be picked up, passed back to a POW camp, and at the end of the war he would rejoin his family... We never fired to kill. My Number One, Bob, used to keep the gun low and wound them in the legs - bring them down. Never fired to kill them. As far as I know he never killed a German. I never did either. Always kept it low."

On 21st September, 1917, a shell hit Patch's Lewis Gun. "The shell that got us was what we called a whizz-bang which burst amongst us. The force of it threw me to the floor, but I didn't realise I'd been hit for a few minutes. The burning hot metal knocks the pain out of you at first but I soon saw blood, so I put a field dressing on it.... I didn't know what had happened to the others at first, but I was told later that I had lost three of my mates. That shell killed Numbers Three, Four and Five. We were a little team together, and those men who were carrying the ammunition were blown to pieces. I reacted very badly. It was like losing a part of my life. It upset me more than anything. We had only been together four months, but with hell going on around us, it seemed like a lifetime."

Harry Patch later recalled: "I'd got this piece of shrapnel right in the groin. It was about two inches long, half an inch thick, with a jagged edge. I was taken to a dressing station and I lay there all that night and the next day, until the evening." The shrapnel was removed without anaesthetic. "Four fellows grabbed me - one on each arm and one on each leg - and I can feel that bloody knife even now, cutting out that shrapnel."

Patch was taken to a hospital ship that took him to Southampton. The wound was so serious that he was never sent back to the Western Front. However, he was not demobilised until after Armistice Day. His experience of the First World War turned him against the idea of using force to solve international conflicts. He wrote in The Last Fighting Tommy that "politicians who took us to war should have been given the guns and told to settle their differences themselves, instead of organising nothing better than legalised mass murder".

After the war Patch got married to Ada and set-up a plumbing business in Bath. He never watched a war film, or talked about his experiences, even to his wife, with whom he had two sons. He worked on a housing scheme at Gobowen, Shropshire, before being invited to work on the Wills Memorial Tower being built at Bristol University. Later he worked as a sanitary engineer.

During the Second World War Patch was a volunteer fireman. He then became a maintenance manager at a US army camp in Street. As he took part in the preparations for D-Day in June 1944 he had to sign the Official Secrets Act.

In 1963 Patch retired from his plumbing business. Ada Patch died in 1978. His second wife Jean died six years later. Patch did not return to Ypres until 2003: "The idea was that I would lay a wreath to the memory of my dead friends, but I couldn't. I looked from the (coach) window and the memories flooded back and I wept, and the wreath was laid on my behalf."

In 2005 Harry Patch met Tony Blair. He told the prime minister hat nobody during the First World War should have been shot for cowardice. "War is organised murder and nothing else." His autobiography, The Last Fighting Tommy, was published in 2007.