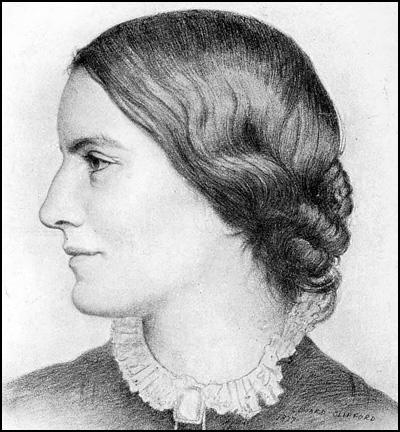

Caroline Southwood Hill

Caroline Southwood Smith, the eldest daughter of Thomas Southwood Smith and Ann Read Smith, the daughter of a Bristol stoneware potter, was born on 21st March 1809. Her father trained at the Baptist academy at Bristol, headed by Dr John Ryland, with the intention of becoming a minister. Smith eventually rebelled against his inherited Calvinism and left the academy in 1808. His parents cut him off, and he never saw them again. (1)

Caroline's mother died in 1812. Southwood Smith left her and her sister Emily with his family in Somerset while he pursued his medical studies in Edinburgh, but the following year he took the unconventional step of taking Caroline to live with him. (2)

As Gillian Darley has pointed out: "For a father to bring up his daughter on his own was a highly unusual arrangement, especially for someone without the means to employ much domestic help. In fact, it was an extremely successful experiment and led to a lifelong intimacy between father and daughter experiment and led to a lifelong intimacy between father and daughter, and an exceptional common purpose between them. Thomas Southwood Smith gave his daughter... an invaluable legacy: he taught her that a combinanation of human sympathy, faith and a powerful sense of purpose could move mountains." (3)

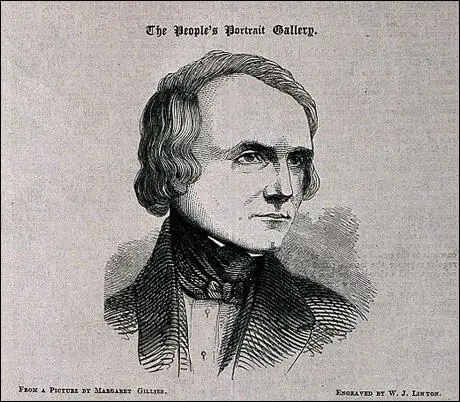

Thomas Southwood Smith

While in the city Thomas Southwood Smith took charge of the city's Unitarian congregation, and succeeded in increasing weekly attendance from 20 to 200. (4) On 28th July 1813 he played a prominent part in the formation of the Scottish Unitarian Association in Glasgow. A fellow member, James Yates (1789–1871), commented that Smith was "a sensible and intelligent man, though not furnished with the advantages of education". (5)

After attaining his MD from Edinburgh University in 1816 Smith settled in Yeovil, as physician and minister to the Unitarian congregation. In 1820 he married Mary Christie and they moved to London. A member of the Royal College of Physicians, he practised privately and served as physician to the Jews' Hospital, and to the London Fever Hospital. By 1821 he had joined the circle of intimates around Jeremy Bentham. This included James Mill, John Stuart Mill, Edwin Chadwick, Francis Place, and Neil Arnott. (6)

Teaching and Marriage

Mary Southwood Smith left her husband and emigrated to the continent in the mid-1820s. Caroline found work teaching at a private school in Wimbledon. She also contributed articles to the Unitarian periodical The Monthly Repository. Her special interest was in the radical educational theories of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi who believed that every aspect of the child's life contributed to the formation of the child's personality, character, and capacity to reason. His educational methods were child-centered and based on individual differences, sense perception, and the student's self-activity. (7)

James Hill, a successful businessman, requested a meeting with Southwood Hill and he offered her the post as governess of his five daughters and a son. In 1835 Hill married Southwood Hill at St Botolphs, Bishopgate. (8) The family lived at 7-8 South Brink, Wisbech. In addition to caring for her six stepchildren she gave birth to five daughters, Miranda (1836), Gertrude (1837), Octavia Hill (1838), Emily (1840) and Florence (1843). "Southwood Hill's unorthodox child-rearing methods became well known in radical circles: she shunned conventional discipline, seeking to instill in the children an ability to reason and a love of learning." (9)

Despite the birth of her children, Caroline Southwood Hill was instrumental in the setting up of James Hill's pioneering infant school which was based upon Robert Owen's New Lanark school, run on Pestalozzian principles. It was housed in the Hall of the People. The school was open in the evenings as a community centre for adult education and recreation. (10)

Margaret Cole has carried out a special study of Robert Owen's educational ideas: "He (Owen) thought education should be natural and spontaneous and the children should enjoy it. He set little store, in the early stage, by learning out of books, but believed that children should learn by means of free discussion, question and answer, by exploration and study of the countryside, and by extensive provision of pictures, maps and charts, and what we should now call Visual Aids... He did not believe in seating children in tidy rows, but letting them roam about freely, in learning to sing and to dance the dances of all countries... He forbade any sort of punishment or even 'harsh critical words', and the strength of his personality, coupled with his love for all children and gift for managing them, secured that neither he nor the teachers who eventually he employed had any trouble with discipline." (11)

Unitarianism

In 1836 Thomas Southwood Smith advocated "a unified profession as against the English separation into oligarchically run corporations of physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries, and denounced the social presumption underlying much English practice." (12) He argued in the Westminster Review that "disease is not aristocratic and plebeian, not to be cured in the gorgeous apartments of the noble and the rich by a refined, elaborate, and recondite skill inapplicable to the chambers of the ignoble and the poor". (13)

In 1837, Parliament passed a Registration Act ordering the registration of all births, marriages and deaths that took place in Britain. Parliament also appointed William Farr to collect and publish these statistics. In his first report for the General Register Office, Farr argued that the evidence indicated that unhealthy living conditions were killing thousands of people every year. (14)

Water consumption in towns per head of population remained very low. In most towns the local river, streams or springs, provided people with water to drink. These sources were often contaminated by human waste. The bacteria of certain very lethal infectious diseases, for example, typhoid and cholera, are transmitted through water, it was not only unpleasant to taste but damaging to people's health. As Alexis de Tocqueville pointed out: "The fetid, muddy waters, stained with a thousand colours by the factories they pass, of one of the streams... wander slowly round this refuge of poverty." (15)

Thomas Southwood Smith associated with a group of Unitariansn in London. This included John Stuart Mill, Harriet Taylor, James Leigh Hunt, William Macready, Margaret Gillies, Mary Gillies, William Johnson Fox, Richard Henry Horne, Robert Browning and Eliza Flower. In 1838, Smith left his wife and set up home with Margaret Gillies. He was joined by Richard Henry Horne and Mary Gillies. This upset most of his Unitarian friends, although Harriet Martineau told her brother, James Martineau, that Smith was "the most wrongfully injured of men". (16)

In 1838 the Poor Law Commission became concerned that a high proportion of all poverty had its origins in disease and premature death. Men were unable to work as a result of long-term health problems. A significant proportion of these men died and the Poor Law Guardians were faced with the expense of maintaining the widow and the orphans. The Commission decided to ask three experienced doctors, Thomas Southwood Smith, James P. Kay-Shuttleworth, and Neil Arnott, to investigate and report on the sanitary condition of some districts in London. (17)

Thomas Southwood Smith, carried out a study of Bethnal Green in London and argued that there was a link between sanitation and disease: " Into this part of the ditch the privies of all the houses of a street called North Street open; these privies are completely uncovered, and the soil from them is allowed to accumulate in the open ditch. Nothing can be conceived more disgusting than the appearance of this ditch for an extent of from 300 to 400 feet, and the odour of the effluvia from it is at this moment most offensive. Lamb's Fields is the fruitful source of fever to the houses which immediately surround it, and to the small streets which branch off from it. Particular houses were pointed out to me from which entire families have been swept away, and from several of the streets fever is never absent." (18)

Caroline Southwood Hill & Robert Owen

Caroline Southwood Hill and her husband greatly admired Robert Owen. In 1836 James Hill launched the radical newspaper, the Star in the East. Hill explained in its first editorial the objectives of the newspaper: "To advocate these principles, to help forward the cause of humanity - to vindicate the claim of the oppressed, and to place in their true light the influencing causes of social suffering and social enjoyment, shall be the grand aim of all our labours as journalists, and in this arduous but satisfactory undertaking, we anticipate the full sympathy and aid of all good men and true." (19)

Hill used his newspaper to promote the United Advancement Society. Members could buy their groceries wholesale; items offered included green and black tea, flour, coffee and soap. (20) It was a co-operative system based on the ideas of Robert Owen. Hill wanted to turn Wisbech into an Owenite town. John F. Harrison, the author of The Common People (1984) points out that "Owenism" was the main British variety of what Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels called utopian socialism. "The Owenites believed that society could be radically transformed by means of experimental communities, in which property was held in common, and social and economic activity was organized on a cooperative basis. This was a method of effecting social change which was radical, peaceful and immediate." (21)

Hill's newspaper chronicled the socialist movement in the country and included scientifically reports and literary reviews. It reported sympathetically the riots that took place in Birmingham in July 1839 following the Chartist petition presented to Parliament by Thomas Attwood. Often the leading article took the form of a letter, usually from one of his opponents, followed by a signed reply from Hill. In his newspaper he attacked the aristocracy and the privileged, local or national figures. (22)

Hill wanted to buy a 700-acre estate at Wretten in Norfolk for his own agricultural colony. He visited it in the autumn of 1838 on behalf of the the United Advancement Society (UAS). In a letter to The Stamford Mercury he explained his plans for the UAS. "The Society is an association of the Working Classes for bettering their condition. It consists of a weekly contribution of sixpence from each member, to enable them by their united means to obtain collectively what individually would be impossible. The first great object which it proposes is to enable them to become landowners... If it is good for the Squire to have land, we do not see that it can be a great disadvantage to the Cottager: the latter possesses the bone and sinew to cultivate it in at least as great a degree as the Squire. The land is then to be cultivated, and the crop, whether wheat or potatoes, either shared amongst the members in equal proportions, or sold at a cheap rate." At this time Hill claimed that 400 people had joined the United Advancement Society. (23)

Hill was unable to raise the money to buy the estate in Wretten and instead, in March 1839 the UAS purchased a mere ten acres just outside Wisbech, on the river. On 13th April the members celebrated, at tables laid out in the orchard, "an event which, though small in its commencement, shall ultimately, be found to have been the beginning of an important change in society." However, the venture was not a success and by November members had begun to withdraw their money from the United Advancement Society. (24)

James Hill was also suffering from financial problems and the last issue of Star in the East was published on 11th April 1840. However, The Times published details of the bankruptcy of James Hill and his partner, Thomas Hill. (25) On 3rd June 1840 an auction was held at the Saracen's Head Inn, Peterborough "by order of the Commissioners in a Fiat of Bankruptcy against James and Thomas Hill, merchants, brewers, and co-partners, and under the direction of the Assignees of the said bankrupts." The sum raised was £12,941. (26)

After the bankruptcy Caroline Southwood Hill and her children were greatly assisted by her father Thomas Southwood Smith and their close friends the radical writer Mary Gillies and her sister Margaret Gillies, with whom Thomas Southwood Smith lived. The family moved from Essex to Hampstead, then to Gloucestershire, and on to Leeds, where in 1845 James Hill bought the Owenite publication the New Moral World. (27)

This was a controversial decision and George Fleming, who was living in Harmony Hill, an Owenite community, attempted to relaunch the paper as Moral World. However, this was not a success and both newspapers stopped publication by the end of the year. (28)

James Hill suffered a nervous breakdown when this venture failed and he went to live with his widowed daughter, Margaret Whelpdale, from his first marriage. Caroline Southwood Hill later wrote: "By the advice of Dr Connolly and other physicians after his recovery he continued to live apart from his wife and her children, and although in this particular instance it may have been an over corrective yet it was grounded on a too little observed fact in human nature, that persons who will be perfectly sound in mind under some conditions, give way if exposed to exciting causes of disease. How many a tragedy might never happen if care were taken to avoid these - if the pressure of pecumiary anxiety for children's sake were lifted off a man for instance or he were kept away from the object of hopeless love or groundless jealousy." (29)

Ladies' Cooperative Guild

Caroline Southwood Hill moved back to London. She began a small school and one of her pupils was Emma Cons. However, when her father became too ill to work in 1852 she was forced to leave. She wanted to become an artist and attended a school run by the mother of the painter Henry Holliday, and then went to the art school in Gower Street, London. Emma Conns also became close friends with Southwood Hill's daughter, Octavia Hill. (30)

In 1852 Caroline Southwood Hill and her daughters became involved in forming the Ladies' Cooperative Guild, a co-operative craft workshop for girls supported by Edward Vansittart Neale and the Christian Socialist movement. Its aim was to give training to disadvantaged girls and young women in the making of ornamental glass and toy furniture. Based at 4 Russell Place, Bloomsbury, it was an early important initiative supporting the drive to increase women's employment opportunities. Southwood was appointed manager and book-keeper. (31)

Caroline Southwood Hill, published an article about the venture in Household Words, a magazine owned by Charles Dickens. "There is a large, light, lofty workshop, situated in one of the best thoroughfares of the town, in which are occupied about two dozen girls between the ages of eight and seventeen. They make choice furniture for dolls houses. They work in groups, each group having its own department of the little trade... A young lady whose age is not so great as that of the majority of the workers - only whose education has been infinitely better - rules over the little band; apportions the work; distributes the material; keeps the accounts; stops the disputes; stimulates the intellect, and directs the recreation of all." She compares her power to the Tsar of Russia "but the two potentates differ in this, that the one governs by fear, the other by affection." (32)

On 30th October 1854, Caroline Southwood Hill attended a meeting organised by Frederick Denison Maurice on his scheme for a Working Men's College. Also in the audience was Emma Cons and Octavia Hill. Southwood Hill became Christian Socialist and fully supported his work on education. The principal of King's College was deeply shocked by the religious views expressed in the Maurice's book, Theological Essays. He brought the issue before the council of the college and it was announced that it had been decided that Maurice's "doctrines were dangerous" and that he been asked to resign from his post as Professor of Theology. (33)

Maurice offered to take a Bible class for the children working in the toy factory. The prospect of Maurice coming to the Ladies' Cooperative Guild horrified the evangelical ladies who supported it, and who sent to it the toymaker children from the Ragged School Union. They threatened to withdraw all support if Maurice gave his Bible class. Caroline Southwood Hill protested, and she was dismissed in late 1855. The Guild did not last long after her departure, although the toymaking carried on for a few more months. (34)

Caroline's daughter, Octavia Hill, also lost her job at the Guild and although John Ruskin gave her some work she feared for the future. On her seventeenth birthday she explained her situation to her friend to Mary Harris: "I intend to continue to support myself if possible, if I can keep body and sould together. I have just completed some work for Ruskin. When I take it home, I intend to learn whether he thinks it any use for me to go on drawing; whether there is any hope of employment... If not, I intend to begin to study with all energy, to qualify myself as a governess." (35)

Final Years

Caroline Southwood Hill now moved to Weybridge. During this period The People and Howitt's Journal published poems and articles on education by Southwood Hill. In 1859 she moved back to London and began teaching full-time once again. After sharing their house for a short period with the pioneer in female medicine Sophia Jex-Blake, in 1862 Caroline, Emily, and Octavia established a school in Nottingham Place, London. Southwood Hill acted as matron, although the school followed Octavia's more disciplinarian principals of education. "Octavia Hill's burgeoning public career sometimes conflicted with her mother's ideals: for example, Octavia's volunteer cadet corps clashed with Caroline's pacifist philosophy." (36)

Caroline Southwood Hill continued to live with her daughters until her death at 6 Cambridge Terrace, St Pancras, London, on 31st December 1902. She was buried in Highgate cemetery.