James Peck

James Peck, the son of Samuel Peck, a prosperous clothing wholesaler, was born in Manhattan, on 14th December, 1914. After graduating from the elite Choate School in Wallingford, Connecticut, he entered Harvard University. (1)

At university he developed a reputation as an independent thinker who espoused idealistic political doctrines. At Harvard he challenged the social and political conventions of the Ivy League elite and shocked his classmates by showing up at the freshman dance with a black date. (2)

Peck recalled in his autobiography that at the dance the other students who "stared at us, whispered, and then stared again." He also was rebelling against his mother who held racist views and "frequently remarked that she would never hire one as a servant because "they are dirty and they steal". (3)

James Peck in Europe

Peck dropped out after his freshman year because "he just decided that the traditional life style of the establishment was not for him." He emigrated to Paris and became very interested in Europen politics. The emergence of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany deepened his commitment to activism and social justice. (4)

In the late 1930s "a severe case of wanderlust and a desire to identify with the working class led to a series of jobs as a merchant seaman, an experience that eventually propelled him into the turbulent world of radical unionism. (5) Peck later commented that his years at sea reinforced his commitment to civil rights. "Living and working aboard ships with interracial crews strenghtened my beliefs in equality." (6)

Peck returned to the United States in 1938 and helped organize the National Maritime Union, which made good use of his skills as a writer and publicist. During these years he became a friend and follower of Roger Baldwin, the founder of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Baldwin encouraged him to join the War Resisters League, and helped him find work as a journalist. (7)

Peck was a pacifist and during the Second World War he was a conscientious objector and an anti-war activist, and spent almost three years in the federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut, where he helped to organize a work strike that led to the desegregation of the prison mess hall. After his release in 1945 he rededicated himself to pacifism and militant trade unionism and became active in a number of progressive organizations. (8)

Journey of Reconciliation

Peck was also a member of the the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). In early 1947, CORE announced plans to send eight white and eight black men into the Deep South to test the Supreme Court ruling that declared segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional. organized by George Houser and Bayard Rustin, the Journey of Reconciliation was to be a two week pilgrimage through Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky. (9)

Although Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) was against this kind of direct action, he volunteered the service of its southern attorneys during the campaign. Thurgood Marshall, head of the NAACP's legal department, was strongly against the Journey of Reconciliation and warned that a "disobedience movement on the part of Negroes and their white allies, if employed in the South, would result in wholesale slaughter with no good achieved." (10)

The Journey of Reconciliation began on 9th April, 1947. The team included George Houser, Bayard Rustin, James Peck, Igal Roodenko, Joseph Felmet, Nathan Wright, Conrad Lynn, Wallace Nelson, Andrew Johnson, Eugene Stanley, Dennis Banks, William Worthy, Louis Adams, Worth Randle and Homer Jack. They were given the following instructions: "If you are a Negro, sit in a front seat. If you are white, sit in a rear seat. If the driver asks you to move, tell him calmly and courteously: 'As an interstate passenger I have a right to sit anywhere in this bus. This is the law as laid down by the United States Supreme Court'. If the driver summons the police and repeats his order in their presence, tell him exactly what you said when he first asked you to move. If the police asks you to 'come along,' without putting you under arrest, tell them you will not go until you are put under arrest. If the police put you under arrest, go with them peacefully. At the police station, phone the nearest headquarters of the NAACP, or one of your lawyers. They will assist you." (11)

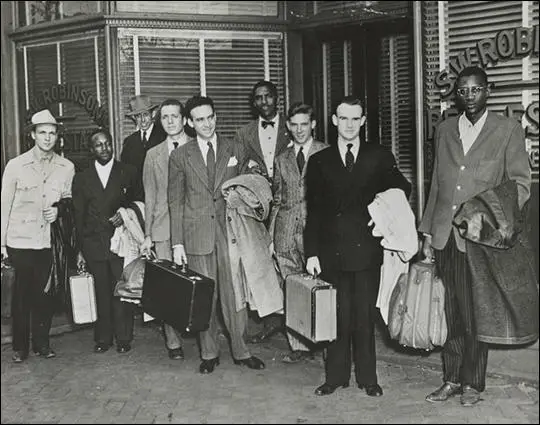

Wallace Nelson, Ernest Bromley, James Peck, Igal Roodenko, Bayard Rustin,

Joseph Felmet, George Houser and Andrew Johnson.

Peck was arrested with Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson in Durham. After being released he was arrested once again in Asheville and charged with breaking local Jim Crow laws. In Chapel Hill Peck and four other members of the team was dragged off the bus and physically assaulted before being taken into custody by the local police. In North Carolina, two of the African Americans, Rustin and Johnson, were found guilty of violating the state's Jim Crow bus statute and were sentenced to thirty days on a chain gang. However, Judge Henry Whitfield made it clear he found that behaviour of the white men even more objectionable. He told Igal Roodenko and Joseph Felmet: "It's about time you Jews from New York learned that you can't come down her bringing your n****** with you to upset the customs of the South. Just to teach you a lesson, I gave your black boys thirty days, and I give you ninety." (12)

The Journey of Reconciliation achieved a great deal of publicity and was the start of a long campaign of direct action by the Congress of Racial Equality. In February 1948 the Council Against Intolerance in America gave George Houser and Bayard Rustin the Thomas Jefferson Award for the Advancement of Democracy for their attempts to bring an end to segregation in interstate travel. (13)

National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy

In 1950 James Peck married Paula Zweier. Over the next few years the couple had two sons, Charles and Samuel. Peck became a founding member of the Committee for Non-Violent Action (CNVA), and gained an international reputation as a militant anti-nuclear activist. In 1958 Albert Bigelow captained the Golden Rule, a protest ship sponsored by CNVA and the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE). Bigelow sailed the thirty-foot ketch into a drop zone in the Pacific to protest America's scheduled testing of nuclear weapons near the island of Eniwetok, he warned President Dwight Eisenhower that even though "our voices have been lost in the massive effort of those responsible for preparing this country for war... we mean to speak now with the weight of our whole lives." (10) Each time, the voyage was foiled by the U.S. Coast Guard and Bigelow was eventually jailed for 60 days in Honolulu - but the attendant publicity provided him with a stage for his political views. (14)

Freedom Riders Campaign

In February, 1961, Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) organised a conference in Kentucky where the organisation laid out its plans to have Freedom Riders challenge the racist policies in the south. It was decided they would ride interstate buses in the South in mixed racial groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. (15) John Lewis, a student at Nashville American Baptist Theological Seminary, commented later: "At this time human dignity is the most important thing in my life. This is the most important decision in my life, to decide to give up all if necessary for the Freedom Ride, that Justice and Freedom might come to the Deep South." (16)

The first bus left Washington on 4th May, 1961, for Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. Members of CORE who travelled on the bus included James Peck, John Lewis, Ed Blankenheim, Hank Thomas, Walter Bergman, Frances Bergman, Genevieve Hughes, James Farmer, Benjamin Elton Cox, Charles Person and Jimmy McDonald. Farmer later recalled: "We were told that the racists, the segregationists, would go to any extent to hold the line on segregation in interstate travel. So when we began the ride I think all of us were prepared for as much violence as could be thrown at us. We were prepared for the possibility of death." (17)

Farmer and his staff tried to come up with a reasonably balanced mixture of black and white, young and old, religious and secular, Northern and Southern. The only deliberate imbalance was a lack of women. The CORE leadership was reluctant to expose women, especially black women, to potentially violent confrontations with white supremacists. "Their decision to limit the number of female Freedom Riders to two was undoubtedly rooted in patriarchal conservatism, but they also feared that a balanced contingent of men and women might be interpreted as a provocative pattern of sexual pairing. The situation was dangerous enough, they reasoned, without taunting the segregationists with visions of interracial sex." (18)

John Lewis, James Peck, Ed Blankenheim, Hank Thomas, Walter Bergman

and James Farmer. Bottom, left to right: Benjamin Elton Cox, Charles Person,

Frances Bergman, Genevieve Hughes and Jimmy McDonald.

President John F. Kennedy was totally opposed to the Freedom Rides. He called Harris Wofford, the president's Special Assistant for Civil Rights and demanded that he do everything to stop them from taking place: "Kennedy's call to me during the Freedom Rides when he said, without any of his customary humor, 'Stop them! Get your friends off those buses!' He felt that Martin Luther King, James Farmer, Bill Coffin, and company were embarrassing him and the country on the eve of the meeting in Vienna with Khrushchev. He supported every American's right to stand up or sit down for his rights - but not to ride for them in the spring of 1961." (19)

Alabama

Governor John Malcolm Patterson of Alabama who had been swept to victory in 1958 on a stridently white supremacist platform, commented that: "The people of Alabama are so enraged that I cannot guarantee protection for this bunch of rabble-rousers." Patterson, who had been elected with the support of the Ku Klux Klan added that integration would come to Alabama only "over my dead body." (20) In his inaugural address Patterson declared: "I will oppose with every ounce of energy I possess and will use every power at my command to prevent any mixing of white and Negro races in the classrooms of this state." (21)

The Birmingham, Police Commissioner, Bull Connor, organized violence against the Freedom Riders with local Ku Klux Klan groups. Gary Thomas Rowe, an FBI informer, and a member of the KKK, reported to his case officer that the mob would have fifteen minutes to attack the Freedom Riders without any arrests being made. Connor said he wanted the Riders to be beaten until "it looked like a bulldog got a hold of them." It was later revealed that J. Edgar Hoover knew the plans for the attack on the Freedom Riders in advance and took no action to prevent the violence. (22)

James Peck later explained: "When the Greyhound bus pulled into Anniston, it was immediately surrounded by an angry mob armed with iron bars. They set about the vehicle, denting the sides, breaking windows, and slashing tires. Finally, the police arrived and the bus managed to depart. But the mob pursued in cars. Within minutes, the pursuing mob was hitting the bus with iron bars. The rear window was broken and a bomb was hurled inside. All the passengers managed to escape before the bus burst into flames and was totally destroyed. Policemen, who had been standing by, belatedly came on the scene. A couple of them fired into the air. The mob dispersed and the injured were taken to a local hospital." (23)

Albert Bigelow later told a committee of inquiry: "Our bus, approaching Anniston, stopped while our driver conversed with the driver of an outgoing bus. A traveler from the bus leaving Anniston station. Outside, no police were in sight. During the fifteen minutes in Anniston, while the mob slashed tires and smashed windows, one policeman appeared in a brown uniform. He did nothing to stop vandalism but fraternized with the mob. A man in a white overall with a dark blue oval insignia on the breast was friendly with the policemen and consulted from time to time with the most active of the mob. Two policemen appeared and cleared a path. The bus left the station. There were no arrests. A few miles out on the highway to Birmingham a tire blow and we pulled to the roadside, the mob after us in about 50 cars. They surrounded us again, yelling and smashing windows, brandishing clubs, chains and pipes; I saw all three." (24)

Some, having just come from church, were dressed in their Sunday best. Ed Blankenheim later recalled: "As a matter of fact, one of the white men who boarded the bus said, 'Y'all ain't in Georgia now, y'all in Alabama.' And with that, he eventually set the bus on fire which was not a good place to be at the time. They held the door shut for maybe ten minutes, they held the door shut... The mob surrounded the bus. The cops would not let the mob get on the bus. So they threw an incendiary device aboard... They were mighty angry people. Really, really vicious. They, as I said, they did surround the bus. They threw a fire bomb aboard and held the door closed. One of the tanks blew up. One of the gas tanks blew up and Hank Thomas, who was one of the Freedom Riders, took advantage of it and was able to force open the bus door, thereby we got off. When we did get off... we had to run through the... these racists who beat us all like hell. Fortunately, well it didn't sound fortunate, the second fuel tank on the bus exploded, scared the hell out of the mob so they uh went on the other side of the highway and the object was to leave us there where we would be blown up." (25)

When the Freedom Riders left the bus they were attacked by baseball bats and iron bars. Genevieve Hughes said she would have been killed but an exploding fuel tank convinced the mob that the whole bus was about to explode and the white bomb retreated. Eventually they were rescued by local police but no attempt was made to identify or arrest those responsible for the assault. (26)

Ed Blankenheim pointed out that: "At the very last moment, an ambulance came and took us to the hospital in Anniston Alabama. There the mob surrounded the bus. They gave the hospital administrators one hour, to let us, to get us out into the parking lot to the mob... Genevieve Hughes and I were the first ones hospitalized because we had pretty weak lungs. We found out all of us couldn't be hospitalized because they don't take blacks in Alabama into the hospital. We refused to go to our rooms and went down to the emergency room with the rest of the Freedom Riders." (27)

Genevieve Hughes later recalled that they were taken to the local hospital. "They admitted me into a ward like room not a private room which is what they had in those days and all the black people were kept on gurneys out in in the corridor they were not admitted to the hospital in any formal since nobody had any injuries that I knew of except for smoke inhalation which was fairly serious but more for me because the smoke bomb had been placed in the seat right opposite of mine and I had probably breathed more smoke than anybody else." (28)

Attack in Montgomery

The surviving bus traveled to Birmingham, Alabama. When they arrived at the Montgomery Greyhound Bus Station they saw an angry mob. Gary Thomas Rowe was a member of the KKK who had arrived in the town that day: "We made an astounding sight... men running and walking down the streets of Birmingham on Sunday afternoon carrying chains, sticks, and clubs. Everything was deserted; no police officers were to be seen except one on a street corner. He stepped off and let us go by, and we barged into the bus station and took it over like an army of occupation. There were Klansmen in the waiting room, in the rest rooms, in the parking area." (29)

James Zwerg later recalled: "As we were going from Birmingham to Montgomery, we'd look out the windows and we were kind of overwhelmed with the show of force - police cars with sub-machine guns attached to the backseats, planes going overhead... We had a real entourage accompanying us. Then, as we hit the city limits, it all just disappeared. As we pulled into the bus station a squad car pulled out - a police squad car. The police later said they knew nothing about our coming, and they did not arrive until after 20 minutes of beatings had taken place. Later we discovered that the instigator of the violence was a police sergeant who took a day off and was a member of the Klan. They knew we were coming. It was a set-up." (30)

The driver had a brief conversation with the white mob. He returned to the bus with a small group of white people and told the passengers: "We have received word that a bus has been burned to the ground and passengers are being carried to the hospital by the carloads. A mob is waiting for our bus and will do the same to us unless we get these blacks off the front seats." The white men began to try and remove Charles Person and Herman K. Harris from the front seat. Walter Bergman and James Peck attempted to intervene but they were soon knocked to the floor. (31)

Harris later testified that there were "two main guys" kicking Bergman, and that they "just kicked him and kicked, just kicked him... his head and shoulders in the back. I thought maybe they would break his, bust his head." The men adhered to Gandhian discipline and refused to fight back and all the men took severe beatings, but this only encouraged their attackers. Walter Bergman was knocked unconscious, and one of the attackers continued to stomp on his chest. Frances Bergman begged the Klansman to stop beating her husband, he ignored her plea. Fortunately, one of the other Klansmen - realizing that the defenceless Freedom Rider was about to be killed - eventually called a halt to the beating. (32)

They adhered to Gandhian discipline and refused to fight back and all the men took severe beatings, but this only encouraged their attackers. Walter Bergman, the oldest of the Freedom Riders at sixty-one, was knocked unconscious, and one of the attackers continued to stomp on his chest. Frances Bergman begged the Klansman to stop beating her husband, he ignored her plea. Fortunately, one of the other Klansmen - realizing that the defenceless Freedom Rider was about to be killed - eventually called a halt to the beating. (33)

During the Freedom Riders campaign the Attorney General Robert Kennedy telephoned Jim Eastland “seven or eight or twelve times each day, about what was going to happen when they got to Mississippi and what needed to be done. That was finally decided was that there wouldn’t be any violence: as they came over the border, they’d lock them all up.” (34)

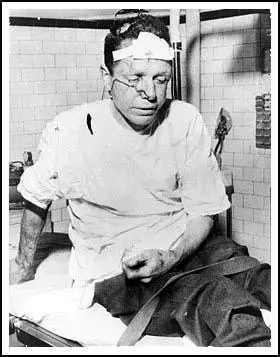

Genevieve Hughes later recalled that it was was James Peck who insisited they continued on the Freedom Ride. "The central figure was Jim Peck and Jim Peck looked like a mummy his head and face were covered with bandages and only his eyes were obvious and his mouth couldn't move and we did have a debate at this occasion about whether to go on. Jim Farmer was not with us. He was back home taking care of a family situation (his father had a serious heart-attack). Jim Peck said we should go on and after that there was not any debate if he couldn't be beaten as he was and still say we should go on we certainly felt we could go on so we all voted unanimously that we would go on and I felt very appalled at seeing Jim Peck but I felt a lot of admiration for him too." (35)

James Peck's wife died in 1972. Eleven years later he suffered a stroke that left him paralyzed on one side. In a 1983 interview, he said: "My life has been nonviolent direct action to try to make this a better world. It is my philosophy that the struggle has to be a non-ending one, because I am not one of those idealists who envision a utopia." (36)

James Peck died on 12th July, 1993.

Primary Sources

(1) James Peck, Freedom Ride (1962)

White cab drivers were hanging around the bus station, with nothing to do. They saw our Trailways bus delayed, and learned the reasons why. Here was something over which they could work out their frustration and boredom. Two ringleaders started haranguing the other drivers. About ten of them started milling around the parked bus. When I got off to put up bail for the two Negroes and two whites in our group who had been arrested, five of the drivers surrounded me. "Coming her to stir up the niggers," snarled a big one with steel-cold grey eyes. With that, he slugged me on the side of the head. I stepped back, looked at him, and asked, "What's the matter?" My failure to retaliate with violence had taken him by surprise.

(2) George Houser and Bayard Rustin, Fellowship Magazine (April, 1947)

Petersburg to Durham, North Carolina, 11th April, 1947:

On the Greyhound to Durham, there were no arrests. Peck and Rustin sat up front. About ten miles out of Petersburg the driver told Rustin to move. When Rustin refused, the driver said he would "attend to that at Blackstone." However, after consultation with other drivers at the bus station in Blackstone, he went on to Clarksville. There the group changed buses. At Oxford, North Carolina, the driver sent for the police, who refused to make an arrest. Persons waiting to get on at Oxford were delayed for forty-five minutes. A middle-aged Negro schoolteacher was permitted to board and to plead with Rustin to move : "Please move. Don't do this. You'll reach your destination either in front or in back. What difference does it make?" Rustin explained his reason for not moving. Other Negro passengers were strong in their support of Rustin, one of them threatening to sue the bus company for the delay. When Durham was reached without arrest, the Negro schoolteacher begged Peck not to use the teacher's name in connection with the incident at Oxford: "It will hurt me in the community. I'll never do that again."

Raleigh to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 12th April:

Lynn and Nelson rode together on the double seat next to the very rear of the Trailways bus, and Houser and Roodenko in front of them. The bus was very crowded. The one other Negro passenger, a woman seated across from Nelson, moved to the very rear voluntarily when a white woman got on the bus and there were no seats in front. When two white college men got on, the driver told Nelson and Lynn to move to the rear seat. When they refused on the basis of their interstate passage, he said the matter would be handled in Durham. A white passenger asked the driver if he wanted any help. The driver replied, "No, we don't want to handle it that way." By the time the group reached Durham, the seating arrangement had changed and the driver did not press the matter.

Durham to Chapel Hill, 12th April:

Johnson and Rustin were in the second seat from the front on a Trailways bus. The driver, as soon as he saw them, asked them to move to the rear. A station superintendent was called to repeat the order. Five minutes later the police arrived and Johnson and Rustin were arrested for refusing to move when ordered to do so. Peck, who was seated in about the middle of the bus, got up after the arrest, saying to the police, "If you arrest them, you'll have to arrest me, too, for I'm going to sit in the rear." The three men were held at the police station for half an hour. They were released without charge when an attorney arrived on their behalf. A suit will be pressed against the company and the police for false arrest. The conversation with the Trailways official indicated that the company knew there was an interracial group making a test. The official said to the police: "We know all about this. Greyhound is letting them ride. But we're not."

Chapel Hill to Greensboro, North Carolina, 13th April:

Johnson and Felmet were seated in front. The driver asked them to move as soon as he boarded. They were arrested quickly, for the police station was just across the street from the bus station. Felmet did not get up to accompany the police until the officer specifically told him he was under arrest. Because he delayed rising from his seat, he was pulled up bodily and shoved out of the bus. The bus driver distributed witness cards to occupants of the bus. One white girl said: "You don't want me to sign one of those. I'm a damn Yankee, and I think this is an outrage." Rustin and Roodenko, sensing the favorable reaction on the bus, decided they would move to the seat in the front vacated by Johnson and Felmet. Their moving forward caused much discussion by passengers. The driver returned soon, and when Rustin and Roodenko refused to move, they were arrested also. A white woman at the front of the bus, a Southerner, gave her name and address to Rustin as he walked by her. The men were arrested on charges of disorderly conduct, for refusing to obey the bus driver and, in the case of the whites, for interfering with arrest. The men were released on $50 bonds.

The bus was delayed nearly two hours. Taxi drivers standing around the bus station were becoming aroused by the events. One hit Peck a hard blow on the head, saying, "Coming down here to stir up the niggers." Peck stood quietly looking at them for several moments, but said nothing. Two persons standing by, one Negro and one white, reprimanded the cab driver for his violence. The Negro was told, "You keep out of this." In the police station, some of the men standing around could be heard saying, "They'll never get a bus out of here tonight." After the bond was placed, Reverend Charles Jones, a local white Presbyterian minister, speedily drove the men to his home. They were pursued by two cabs filled with taxi men. As the interracial group reached the front porch of the Jones home, the two cabs pulled up at the curb. Men jumped out, two of them with sticks for weapons; others picked up sizable rocks. They started toward the house, but were called back by one of their number. In a few moments the phone rang, and an anonymous voice said to Jones, "Get those damn niggers out of town or we'll burn your house down. We'll be around to see that they go." The police were notified and arrived in about twenty minutes. The interracial group felt it wise to leave town before nightfall. Two cars were obtained and the group was driven to Greensboro, by way of Durham, for an evening engagement.

Greensboro to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, 14th April:

Two tests were made on Greyhound buses. In the first test Lynn sat in front; in the second, Nelson. A South Carolinian seated by Bromley on the first bus said, "In my state he would either move or be killed." He was calm as Bromley talked with him about the Morgan decision.

Winston-Salem to Asheville, North Carolina, 15th April:

From Winston-Salem to Statesville the group traveled by Greyhound. Nelson was seated with Bromley in the second seat from the front. Nothing was said. At Statesville, the group transferred to the Trailways, with Nelson still in front. In a small town about ten miles from Statesville, the driver approached Nelson and told him he would have to move to the rear. When Nelson said that he was an interstate passenger, the driver said that the bus was not interstate. When Nelson explained that his ticket was interstate, the driver returned to his seat and drove on. The rest of the trip to Asheville was through mountainous country, and the bus stopped at many small towns. A soldier asked the driver why Nelson was not forced to move. The driver explained that there was a Supreme Court decision and that he could do nothing about it. He said, "If you want to do something about this, don't blame this man [Nelson]; kill those bastards up in Washington." The soldier explained to a rather large, vociferous man why Nelson was allowed to sit up front. The large man commented, "I wish I was the bus driver." Near Asheville the bus became very crowded, and there were women standing up. Two women spoke to the bus driver, asking him why Nelson was not moved. In each case the driver explained that the Supreme Court decision was responsible. Several white women took seats in the Jim Crow section in the rear.

Asheville to Knoxville, Tennessee, 17th April

Banks and Peck were in the second seat on the Trailways. While the bus was still in the station, a white passenger asked the bus driver to tell Banks to move. Banks replied, "I'm Sorry, I can't," and explained that he was an interstate passenger. The police were called and the order repeated. A twenty-minute consultation took place before the arrest was made. When Peck was not arrested, he said, "We're traveling together, and you will have to arrest me too." He was arrested for sitting in the rear. The two men were released from the city jail on $400 bond each.

(3) James Peck, a member of the Freedom Rides, wrote about his experiences in Alabama on 14th May, 1961, in his book, Freedom Rider (1962)

When the Greyhound bus pulled into Anniston, it was immediately surrounded by an angry mob armed with iron bars. They set about the vehicle, denting the sides, breaking windows, and slashing tires. Finally, the police arrived and the bus managed to depart. But the mob pursued in cars. Within minutes, the pursuing mob was hitting the bus with iron bars. The rear window was broken and a bomb was hurled inside. All the passengers managed to escape before the bus burst into flames and was totally destroyed. Policemen, who had been standing by, belatedly came on the scene. A couple of them fired into the air. The mob dispersed and the injured were taken to a local hospital.

(4) The New York Times (7th September, 1964)

The American. Civil Liberties Union has protested to the Attorney General's office against the interrogation of James Peck an author, by Immigration Service officials on his return July 27 from a trip to Europe.

Mr. Peck, a civil rights and pacifism worker, who wrote “Freedom Road,” said he had been temporarily detained at Kennedy International Airport after he had refused on principle to answer a question as to whether he had been to Cuba. Travel to Cuba is barred under provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

The union suggested that Mr. Peck was interrogated because of his “attachment to pacifism and civil rights,” and urged that the service be directed to apologize to him.

(4) Eric Pace, The New York Times (13th July, 1993)

James Peck, a union organizer and pacifist who became widely known as a civil rights worker in the 1960's, died yesterday at Walker Methodist Nursing Home in Minneapolis, where he had lived for about eight years. He was 78 and formerly lived in Manhattan.

The cause of his death was not clear, said his son Dr. Charles Peck, who added that his father had been paralyzed on one side since a stroke 10 years ago.

For more than four decades, Mr. Peck, known as Jim, promoted a variety of social causes. His activities included pro-union work among seamen in the 1930's, detention as a conscientious objector in the 1940's, civil rights demonstrations in the South in the 1960's and envelope-stuffing on behalf of Amnesty International in the 1980's.

In a 1983 interview, not long after his stroke, he said: "My life has been nonviolent direct action to try to make this a better world. It is my philosophy that the struggle has to be a non-ending one, because I am not one of those idealists who envision a utopia."

Mr. Peck, who was white, was an early member of the Congress for Racial Equality, which is based in New York. He was on its national action committee and for more than a decade edited one of the civil rights group's publications.

In 1961 he and other CORE members participated in a "freedom ride" from Washington to Mississippi to test a Supreme Court ruling that prohibited segregation on interstate buses. When the group got off their bus in Birmingham, Ala., they were severely beaten with clubs by about 20 white men.

Mr. Peck's face was "a mass of blood," said the television journalist Howard K. Smith, who was in Birmingham on assignment for CBS News. More than 50 sutures were needed to close his wounds.

Mr. Peck was born in Manhattan, the son of Samuel Peck, a prosperous clothing wholesaler. He grew up there and graduated from the Choate School in Wallingford, Conn. He entered Harvard University but dropped out after his freshman year because, as his son Charles put it yesterday, "he just decided that the traditional life style of the establishment was not for him."

He went to Paris for a couple of years, and after that, he worked as a seaman for several years, becoming active in the formation of what became the National Maritime Union.

At the suggestion of Roger Baldwin of the American Civil Liberties Union, he began working for a news syndicate that served trade union publications. He also did volunteer work in the early civil rights movement.

In 1940, he declared himself a conscientious objector and worked with the War Resisters League before the United States entered World War II. During the war, he was interned for more than two years in Danbury, Conn., as a conscientious objector.

After the war, he continued to work on behalf of the league as well as CORE. In 1947 he was among demonstrators who burned their draft cards outside the White House.

He continued his antiwar efforts during the Vietnam War, helping to organize protests and advising young men eligible for the draft.

In 1983, a Federal judge in New York awarded him $25,000 in a suit that he had filed in 1976, contending that the Federal Bureau of Investigation could have prevented the attack on him in Birmingham.

He wrote three books: We Who Would Not Kill, which came out in the 1950's, Freedom Ride, which appeared in the mid-1960's, and Upper Dogs Versus Underdog, which came out in the 1970's.

His wife of 22 years, the former Paula Zweier, died in 1972.

In addition to his son Charles, who lives in Minneapolis, Mr. Peck is survived by another son, Samuel Peck, of Del Mar, Calif., and four grandchildren.