Journey of Reconciliation

In 1942 three members of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), George Houser, James Farmer and Berniece Fisher established the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). Members of CORE had been deeply influenced by the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and the nonviolent civil disobedience campaign that he used successfully against British rule in India. The students became convinced that the same methods could be employed by African Americans to obtain civil rights in America.

In early 1947, the Congress on Racial Equality announced plans to send eight white and eight black men into the Deep South to test the Supreme Court ruling that declared segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional. organized by George Houser and Bayard Rustin, the Journey of Reconciliation was to be a two week pilgrimage through Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky.

Although Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) was against this kind of direct action, he volunteered the service of its southern attorneys during the campaign. Thurgood Marshall, head of the NAACP's legal department, was strongly against the Journey of Reconciliation and warned that a "disobedience movement on the part of Negroes and their white allies, if employed in the South, would result in wholesale slaughter with no good achieved."

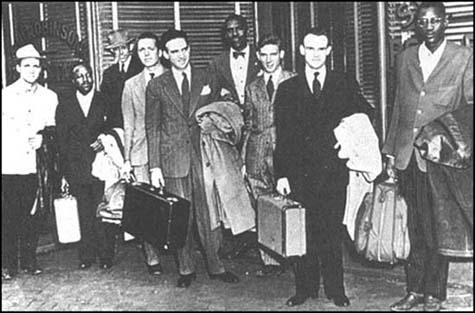

The Journey of Reconciliation began on 9th April, 1947. The team included Igal Roodenko, George Houser, Bayard Rustin, James Peck, Joseph Felmet, Nathan Wright, Conrad Lynn, Wallace Nelson, Andrew Johnson, Eugene Stanley, Dennis Banks, William Worthy, Louis Adams, Worth Randle and Homer Jack.

Randle, Wallace Nelson, Ernest Bromley, James Peck, Igal Roodenko,

Bayard Rustin, Joseph Felmet, George Houser and Andrew Johnson.

James Peck was arrested with Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson in Durham. After being released he was arrested once again in Asheville and charged with breaking local Jim Crow laws. In Chapel Hill Peck and four other members of the team was dragged off the bus and physically assaulted before being taken into custody by the local police.

Members of the Journey of Reconciliation team were arrested several times. In North Carolina, two of the African Americans, Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson, were found guilty of violating the state's Jim Crow bus statute and were sentenced to thirty days on a chain gang. However, Judge Henry Whitfield made it clear he found that behaviour of the white men even more objectionable. He told Igal Roodenko and Joseph Felmet: "It's about time you Jews from New York learned that you can't come down her bringing your ******s with you to upset the customs of the South. Just to teach you a lesson, I gave your black boys thirty days, and I give you ninety."

The Journey of Reconciliation achieved a great deal of publicity and was the start of a long campaign of direct action by the Congress of Racial Equality. In February 1948 the Council Against Intolerance in America gave George Houser and Bayard Rustin the Thomas Jefferson Award for the Advancement of Democracy for their attempts to bring an end to segregation in interstate travel.

George Houser later wrote: "We in the non-violent movement of the 1940s certainly thought that we were initiating something of importance in American life. Of course, we weren't able to put it in perspective then. But we were filled with vim and vigor, and we hoped that a mass movement could develop, even if we did not think that we were going to produce it. In retrospect, I would say we were precursors. The things we did in the 1940s were the same things that ushered the civil rights revolution."

Primary Sources

(1) Bayard Rustin wrote an article for the Louisiana Weekly, to reply to what Thurgood Marshall had said about the Congress on Racial Equality's decision to organize the Journey of Reconciliation (1st April, 1947)

I am sure that Marshall is either ill-formed on the principles and techniques of nonviolence or ignorant of the process of social change.

Unjust social laws and patterns do not change because supreme courts deliver just decisions. One needs merely to observe the continued practice of Jim Crow in interstate travel, six months after the Supreme Court's decision, to see the necessity of resistance. Social progress comes from struggle; all freedom demands a price.

At times freedom will demand that its followers go into situations where even death is to be faced. Resistance on the buses would, for example, mean humiliation, mistreatment by police, arrest, and some physical violence inflicted on the participants.

But if anyone at this date in history believes that the "white problem," which is one of privilege, can be settled without some violence, he is mistaken and fails to realize the ends to which men can be driven to hold on to what they consider their privileges.

This is why Negroes and whites who participate in direct action must pledge themselves to non-violence in word and deed. For in this way alone can the inevitable violence be reduced to a minimum.

(2) Instructions produced by George Houser and Bayard Rustin for the Journey of Reconciliation (April, 1947)

If you are a Negro, sit in a front seat. If you are white, sit in a rear seat.

If the driver asks you to move, tell him calmly and courteously: "As an interstate passenger I have a right to sit anywhere in this bus. This is the law as laid down by the United States Supreme Court".

If the driver summons the police and repeats his order in their presence, tell him exactly what you said when he first asked you to move.

If the police asks you to "come along," without putting you under arrest, tell them you will not go until you are put under arrest.

If the police put you under arrest, go with them peacefully. At the police station, phone the nearest headquarters of the NAACP, or one of your lawyers. They will assist you.

(3) George Houser and Bayard Rustin, Fellowship Magazine (April, 1947)

On June 3, 1946, the Supreme Court of the United States announced its decision in the case of Irene Morgan versus the Commonwealth of Virginia. State laws demanding segregation of interstate passengers on motor carriers are now unconstitutional, for segregation of passengers crossing state lines was declared an "undue burden on interstate commerce." Thus it was decided that state Jim Crow laws do not affect interstate travelers. In a later decision in the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, the Morgan decision was interpreted to apply to interstate train travel as well as bus travel.

The executive committee of the Congress of Racial Equality and the racial-industrial committee of the Fellowship of Reconciliation decided that they should jointly sponsor a "Journey of Reconciliation" through the upper South, in order to determine to how great an extent bus and train companies were recognizing the Morgan decision. They also wished to learn the reaction of bus drivers, passengers, and police to those who nonviolently and persistently challenge Jim Crow in interstate travel.

During the two-week period from April 9 to April 23, 1947, an interracial group of men, traveling as a deputation team, visited fifteen cities in Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky. More than thirty speaking engagements were met before church, NAACP, and college groups. The sixteen participants were:

Negro. Bayard Rustin, of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and part-time worker with the American Friends Service Committee; Wallace Nelson, freelance lecturer; Conrad Lynn, New York attorney; Andrew Johnson, Cincinnati student; Dennis Banks, Chicago musician; William Worthy, of the New York Council for a Permanent FEPC; Eugene Stanley, of A. and T. College, Greensboro, North Carolina; Nathan Wright, church social worker from Cincinnati.

White. George Houser, of the FOR and executive secretary of the Congress of Racial Equality; Ernest Bromley, Methodist minister from North Carolina; James Peck, editor of the Workers Defense League News Bulletin; Igal Roodenko, New York horticulturist; Worth Randle, Cincinnati biologist; Joseph Felmet, of the Southern Workers Defense League; Homer Jack, executive secretary of the Chicago Council Against Racial and Religious Discrimination; Louis Adams, Methodist minister from North Carolina.

During the two weeks of the trip, twenty-six tests of company policies were made. Arrests occurred on six occasions, with a total of twelve men arrested.

(4) George Houser and Bayard Rustin, report on Journey of Reconciliation (1947)

Petersburg to Durham, North Carolina, 11th April, 1947

On the Greyhound to Durham, there were no arrests. Peck and Rustin sat up front. About ten miles out of Petersburg the driver told Rustin to move. When Rustin refused, the driver said he would "attend to that at Blackstone." However, after consultation with other drivers at the bus station in Blackstone, he went on to Clarksville. There the group changed buses. At Oxford, North Carolina, the driver sent for the police, who refused to make an arrest. Persons waiting to get on at Oxford were delayed for forty-five minutes. A middle-aged Negro schoolteacher was permitted to board and to plead with Rustin to move : "Please move. Don't do this. You'll reach your destination either in front or in back. What difference does it make?" Rustin explained his reason for not moving. Other Negro passengers were strong in their support of Rustin, one of them threatening to sue the bus company for the delay. When Durham was reached without arrest, the Negro schoolteacher begged Peck not to use the teacher's name in connection with the incident at Oxford: "It will hurt me in the community. I'll never do that again."

Raleigh to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 12th April

Lynn and Nelson rode together on the double seat next to the very rear of the Trailways bus, and Houser and Roodenko in front of them. The bus was very crowded. The one other Negro passenger, a woman seated across from Nelson, moved to the very rear voluntarily when a white woman got on the bus and there were no seats in front. When two white college men got on, the driver told Nelson and Lynn to move to the rear seat. When they refused on the basis of their interstate passage, he said the matter would be handled in Durham. A white passenger asked the driver if he wanted any help. The driver replied, "No, we don't want to handle it that way." By the time the group reached Durham, the seating arrangement had changed and the driver did not press the matter.

Durham to Chapel Hill, 12th April

Johnson and Rustin were in the second seat from the front on a Trailways bus. The driver, as soon as he saw them, asked them to move to the rear. A station superintendent was called to repeat the order. Five minutes later the police arrived and Johnson and Rustin were arrested for refusing to move when ordered to do so. Peck, who was seated in about the middle of the bus, got up after the arrest, saying to the police, "If you arrest them, you'll have to arrest me, too, for I'm going to sit in the rear." The three men were held at the police station for half an hour. They were released without charge when an attorney arrived on their behalf. A suit will be pressed against the company and the police for false arrest. The conversation with the Trailways official indicated that the company knew there was an interracial group making a test. The official said to the police: "We know all about this. Greyhound is letting them ride. But we're not."

Chapel Hill to Greensboro, North Carolina, 13th April

Johnson and Felmet were seated in front. The driver asked them to move as soon as he boarded. They were arrested quickly, for the police station was just across the street from the bus station. Felmet did not get up to accompany the police until the officer specifically told him he was under arrest. Because he delayed rising from his seat, he was pulled up bodily and shoved out of the bus. The bus driver distributed witness cards to occupants of the bus. One white girl said: "You don't want me to sign one of those. I'm a damn Yankee, and I think this is an outrage." Rustin and Roodenko, sensing the favorable reaction on the bus, decided they would move to the seat in the front vacated by Johnson and Felmet. Their moving forward caused much discussion by passengers. The driver returned soon, and when Rustin and Roodenko refused to move, they were arrested also. A white woman at the front of the bus, a Southerner, gave her name and address to Rustin as he walked by her. The men were arrested on charges of disorderly conduct, for refusing to obey the bus driver and, in the case of the whites, for interfering with arrest. The men were released on $50 bonds.

The bus was delayed nearly two hours. Taxi drivers standing around the bus station were becoming aroused by the events. One hit Peck a hard blow on the head, saying, "Coming down here to stir up the ******s." Peck stood quietly looking at them for several moments, but said nothing. Two persons standing by, one Negro and one white, reprimanded the cab driver for his violence. The Negro was told, "You keep out of this." In the police station, some of the men standing around could be heard saying, "They'll never get a bus out of here tonight." After the bond was placed, Reverend Charles Jones, a local white Presbyterian minister, speedily drove the men to his home. They were pursued by two cabs filled with taxi men. As the interracial group reached the front porch of the Jones home, the two cabs pulled up at the curb. Men jumped out, two of them with sticks for weapons; others picked up sizable rocks. They started toward the house, but were called back by one of their number. In a few moments the phone rang, and an anonymous voice said to Jones, "Get those damn ******s out of town or we'll burn your house down. We'll be around to see that they go." The police were notified and arrived in about twenty minutes. The interracial group felt it wise to leave town before nightfall. Two cars were obtained and the group was driven to Greensboro, by way of Durham, for an evening engagement.

Greensboro to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, 14th April

Two tests were made on Greyhound buses. In the first test Lynn sat in front; in the second, Nelson. A South Carolinian seated by Bromley on the first bus said, "In my state he would either move or be killed." He was calm as Bromley talked with him about the Morgan decision.

Winston-Salem to Asheville, North Carolina, 15th April

From Winston-Salem to Statesville the group traveled by Greyhound. Nelson was seated with Bromley in the second seat from the front. Nothing was said. At Statesville, the group transferred to the Trailways, with Nelson still in front. In a small town about ten miles from Statesville, the driver approached Nelson and told him he would have to move to the rear. When Nelson said that he was an interstate passenger, the driver said that the bus was not interstate. When Nelson explained that his ticket was interstate, the driver returned to his seat and drove on. The rest of the trip to Asheville was through mountainous country, and the bus stopped at many small towns. A soldier asked the driver why Nelson was not forced to move. The driver explained that there was a Supreme Court decision and that he could do nothing about it. He said, "If you want to do something about this, don't blame this man [Nelson]; kill those bastards up in Washington." The soldier explained to a rather large, vociferous man why Nelson was allowed to sit up front. The large man commented, "I wish I was the bus driver." Near Asheville the bus became very crowded, and there were women standing up. Two women spoke to the bus driver, asking him why Nelson was not moved. In each case the driver explained that the Supreme Court decision was responsible. Several white women took seats in the Jim Crow section in the rear.

Asheville to Knoxville, Tennessee, 17th April

Banks and Peck were in the second seat on the Trailways. While the bus was still in the station, a white passenger asked the bus driver to tell Banks to move. Banks replied, "I'm Sorry, I can't," and explained that he was an interstate passenger. The police were called and the order repeated. A twenty-minute consultation took place before the arrest was made. When Peck was not arrested, he said, "We're traveling together, and you will have to arrest me too." He was arrested for sitting in the rear. The two men were released from the city jail on $400 bond each.

(5) James Peck, Freedom Ride (1962)

White cab drivers were hanging around the bus station, with nothing to do. They saw our Trailways bus delayed, and learned the reasons why. Here was something over which they could work out their frustration and boredom. Two ringleaders started haranguing the other drivers. About ten of them started milling around the parked bus. When I got off to put up bail for the two Negroes and two whites in our group who had been arrested, five of the drivers surrounded me. "Coming her to stir up the ******s," snarled a big one with steel-cold grey eyes. With that, he slugged me on the side of the head. I stepped back, looked at him, and asked, "What's the matter?" My failure to retaliate with violence had taken him by surprise.

(6) George Houser, interviewed by Jervis Anderson for his book, A. Philip Randolph: A Biographical Portrait (1972)

We in the non-violent movement of the 1940s certainly thought that we were initiating something of importance in American life. Of course, we weren't able to put it in perspective then. But we were filled with vim and vigor, and we hoped that a mass movement could develop, even if we did not think that we were going to produce it. In retrospect, I would say we were precursors. The things we did in the 1940s were the same things that ushered the civil rights revolution. Our Journey of Reconciliation preceded the Freedom Rides of 1961 by fourteen years. Conditions were not quite ready for the full-blown movement when we were undertaking our initial actions. But I think we helped to lay the foundations for what followed, and I feel proud of that.